A leap year (also known as an intercalary year or bissextile year) is a calendar year that contains an additional day (or, in the case of a lunisolar calendar, a month) added to keep the calendar year synchronized with the astronomical year or seasonal year.[1] Because astronomical events and seasons do not repeat in a whole number of days, calendars that have a constant number of days in each year will unavoidably drift over time with respect to the event that the year is supposed to track, such as seasons. By inserting (called intercalating in technical terminology) an additional day or month into some years, the drift between a civilization’s dating system and the physical properties of the Solar System can be corrected. A year that is not a leap year is a common year.

For example, in the Gregorian calendar, each leap year has 366 days instead of 365, by extending February to 29 days rather than the common 28. These extra days occur in each year that is an integer multiple of 4 (except for years evenly divisible by 100, but not by 400). The leap year of 366 days has 52 weeks and two days, hence the year following a leap year will start later by two days of the week.

In the lunisolar Hebrew calendar, Adar Aleph, a 13th lunar month, is added seven times every 19 years to the twelve lunar months in its common years to keep its calendar year from drifting through the seasons. In the Bahá’í Calendar, a leap day is added when needed to ensure that the following year begins on the March equinox.

The term leap year probably comes from the fact that a fixed date in the Gregorian calendar normally advances one day of the week from one year to the next, but the day of the week in the 12 months following the leap day (from March 1 through February 28 of the following year) will advance two days due to the extra day, thus leaping over one day in the week.[2][3] For example, Christmas Day (December 25) fell on a Sunday in 2016, Monday in 2017, Tuesday in 2018, and Wednesday in 2019, but then leapt over Thursday to fall on a Friday in 2020.

The length of a day is also occasionally corrected by inserting a leap second into Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) because of variations in Earth’s rotation period. Unlike leap days, leap seconds are not introduced on a regular schedule because variations in the length of the day are not entirely predictable.

Leap years can present a problem in computing, known as the leap year bug, when a year is not correctly identified as a leap year or when February 29 is not handled correctly in logic that accepts or manipulates dates.

Julian calendar[edit]

On 1 January 45 BC, by edict, Julius Caesar reformed the historic Roman calendar to make it a consistent solar calendar (rather than one which was neither strictly lunar nor strictly solar), thus removing the need for frequent intercalary months. His rule for leap years was a simple one: add a leap day every four years. This algorithm is close to reality: a Julian year lasts 365.25 days, a mean tropical year about 365.2422 days.[4] Consequently, even this Julian calendar drifts out of ‘true’ by about three days every 400 years. The Julian calendar continued in use unaltered for about 1600 years until the Catholic Church became concerned about the widening divergence between the March Equinox and 21 March, as explained at Gregorian calendar, below.

Gregorian calendar[edit]

An image showing which century years are leap years in the Gregorian calendar

In the Gregorian calendar, the standard calendar in most of the world,[5] most years that are multiples of 4 are leap years. In each leap year, the month of February has 29 days instead of 28. Adding one extra day in the calendar every four years compensates for the fact that a period of 365 days is shorter than a tropical year by almost 6 hours.[6] Some exceptions to this basic rule are required since the duration of a tropical year is slightly less than 365.25 days. The Gregorian reform modified the Julian calendar’s scheme of leap years as follows:

Every year that is exactly divisible by four is a leap year, except for years that are exactly divisible by 100, but these centurial years are leap years if they are exactly divisible by 400. For example, the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not leap years, but the years 1600 and 2000 are.[7]

Over a period of four centuries, the accumulated error of adding a leap day every four years amounts to about three extra days. The Gregorian calendar therefore omits three leap days every 400 years, which is the length of its leap cycle. This is done by omitting February 29 in the three century years (multiples of 100) that are not multiples of 400.[8][9] The years 2000 and 2400 are leap years, but not 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200 and 2300. By this rule, an entire leap cycle is 400 years which total 146,097 days, and the average number of days per year is 365 + 1⁄4 − 1⁄100 + 1⁄400 = 365 + 97⁄400 = 365.2425.[10] (This rule could be applied to years before the Gregorian reform to create a proleptic Gregorian calendar,[11] though the result would not match any historical records.

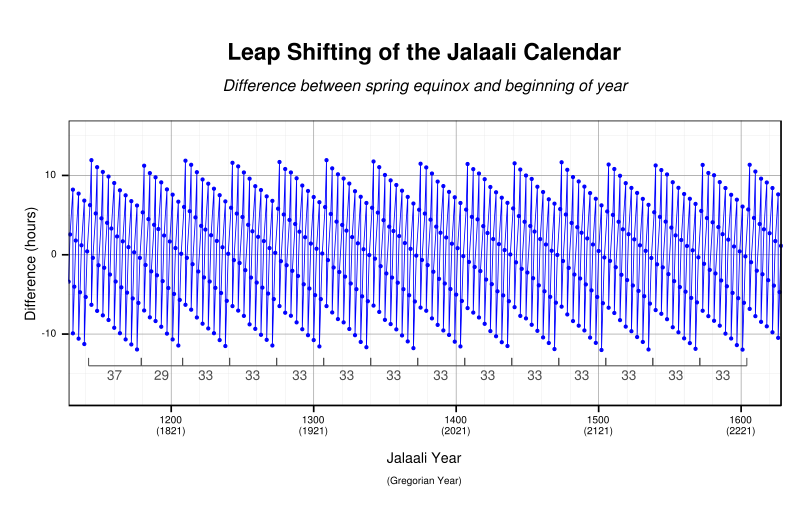

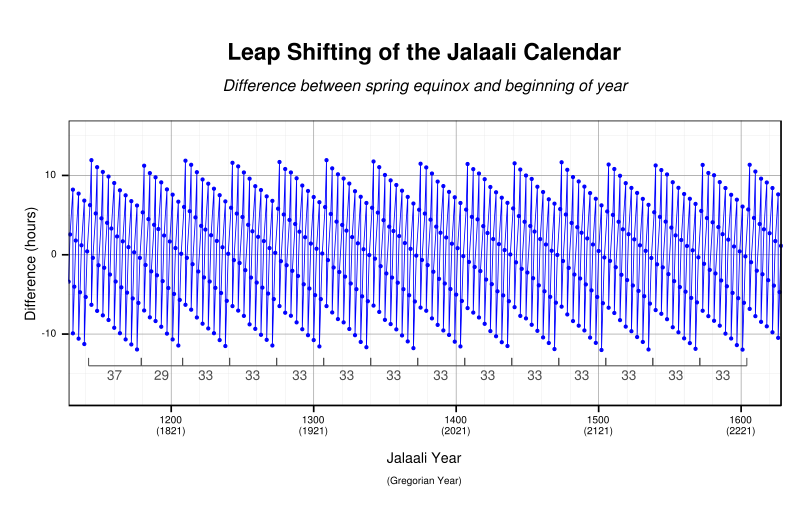

This graph shows the variations in date and time of the June Solstice due to unequally spaced «leap day» rules. Contrast this with the Iranian Solar Hijri calendar, which generally has 8 leap year days every 33 years.

The Gregorian calendar was designed to keep the vernal equinox on or close to March 21, so that the date of Easter (celebrated on the Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon that falls on or after March 21) remains close to the vernal equinox.[12] The «Accuracy» section of the «Gregorian calendar» article discusses how well the Gregorian calendar achieves this design goal, and how well it approximates the tropical year.

Leap day in the Julian and Gregorian calendars [edit]

A Swedish pocket calendar from 2008 showing February 29

February 1900 calendar showing that 1900 was not a leap year

The intercalary day that usually occurs every four years is called the leap day and is created by adding an extra day to February. This day is added to the calendar in leap years as a corrective measure because the Earth does not orbit the Sun in precisely 365 days. Since about the fifteenth century, this extra day is February 29, but when the Julian calendar was introduced, leap day was handled differently in two respects. First, leap day fell within February and not at the end: February 24 was doubled to create the (strange to modern eyes) two days both dated February 24.[13] Second, the leap day was simply not counted so that a leap year still had 365 days.[14][page needed]

Early Roman practice[edit]

The early Roman calendar was a lunisolar one that consisted of 12 months, for a total of 355 days. In addition, a 27- or 28-day intercalary month, the Mensis Intercalaris, was sometimes inserted into February, at the first or second day after the Terminalia a. d. VII Kal. Mar., (February 23), to resynchronise the lunar and solar cycles. The remaining days of Februarius were discarded. This intercalary month, named Intercalaris or Mercedonius, contained 27 days. The religious festivals that were normally celebrated in the last five days of February were moved to the last five days of Intercalaris. The lunisolar calendar was abandoned about 450 BC by the decemviri,[15] who implemented the Roman Republican calendar, used until 46 BC. The days of these calendars were counted down (inclusively) to the next named day, so February 24 was ante diem sextum Kalendas Martias [«the sixth day before the calends of March»] often abbreviated a. d. VI Kal. Mart. The Romans counted days inclusively in their calendars, so this was actually the fifth day before March 1 when counted in the modern exclusive manner (i.e., not including both the starting and ending day).[16] Because only 22 or 23 days were effectively added, not a full lunation, the calends and ides of the Roman Republican calendar were no longer associated with the new moon and full moon.

Julian reform[edit]

In Caesar’s revised calendar, there was just one intercalary day – nowadays called the leap day – to be inserted every fourth year and this too was done after 23 of February. To create the intercalary day, the existing ante diem sextum Kalendas Martias ([sixth day before the Kalends (first day) of March], February 24) was doubled,[17] producing ante diem bis sextum Kalendas Martias [a second sixth day before the Kalends (first day) of March]. This bis sextum [«twice sixth»] was translated as ‘bissextile’: the ‘bissextile day’ is the leap day and a ‘bissextile year’ is a year which includes a leap day.[18] This second instance of the sixth day before the Kalends of March was inserted in calendars between the ‘normal’ fifth and sixth days. By a legal fiction, the Romans treated both the first «sixth day» and the additional «sixth day» before the Kalends of March as one day. Thus a child born on either of those days in a leap year would have its first birthday on the following sixth day before the Kalends of March. In a leap year in the original Julian calendar, there were indeed two days both numbered 24 February. This practice continued for another fifteen to seventeen centuries, even after most countries had adopted the Gregorian calendar.

For legal purposes, the two days of the bis sextum were considered to be a single day, with the second sixth being intercalated; but in common practice by 238, when Censorinus wrote, the intercalary day was followed by the last five days of February, a. d. VI, V, IV, III and pridie Kal. Mart. (the days numbered 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28 from the beginning of February in a common year), so that the intercalated day was the first of the doubled pair. Thus the intercalated day was effectively inserted between the 23rd and 24th days of February. All later writers, including Macrobius about 430, Bede in 725, and other medieval computists (calculators of Easter), continued to state that the bissextum (bissextile day) occurred before the last five days of February.[citation needed]

In England, the Church and civil society continued the Roman practice whereby the leap day was simply not counted so that a leap year was only reckoned as 365 days. Henry III’s 1236 Statute De Anno et Die Bissextili[a] instructed magistrates to treat the leap day and the day before as one day.[19][18] The practical application of the rule is obscure. It was regarded as in force in the time of the famous lawyer Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) because he cites it in his Institutes of the Lawes of England. However, Coke merely quotes the act with a short translation and does not give practical examples.[20]

‘ … and by (b) the statute de anno bissextili, it is provided, quod computentur dies ille excrescens et dies proxime præcedens pro unico dii, so as in computation that day excrescent is not accounted.’

29 February[edit]

Replacement (by 29 February) of the awkward practice of having two days with the same date appears to have evolved by custom and practice, the etymological origin of the term «bissextile» seeming to have been lost.[13] In England in the course of the fifteenth century, «29 February» appears increasingly often in legal documents – although the records of the proceedings of the House of Commons of England continued to use the old system until the middle of the sixteenth century.[13] It was not until passage of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 that 29 February was formally recognised in British law.[21][b]

Liturgical practices[edit]

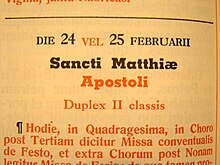

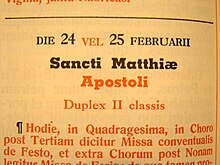

In the older Roman Missal, feast days falling on or after February 24 are celebrated one day later in a leap year.

In the liturgical calendar of the Christian churches, the placement of the leap day is significant because of the date of the feast of Saint Matthias, which is defined as the sixth day before March 1 (counting inclusively). The Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer was still using the «two days with the same date» system in its 1542 edition;[23] it first included a calendar which used entirely consecutive day counting from 1662 and showed leap day as falling on 29 February.[24] In the 1680s, the Church of England declared 25 February to be the feast of St Matthias.[25]

Until 1970, the Roman Catholic Church always celebrated the feast of Saint Matthias on a. d. VI Kal. Mart., so if the days were numbered from the beginning of the month, it was named February 24 in common years, but the presence of the bissextum in a bissextile year immediately before a. d. VI Kal. Mart. shifted the latter day to February 25 in leap years, with the Vigil of St. Matthias shifting from February 23 to the leap day of February 24. This shift did not take place in pre-Reformation Norway and Iceland; Pope Alexander III ruled that either practice was lawful.[26] Other feasts normally falling on February 25–28 in common years are also shifted to the following day in a leap year (although they would be on the same day according to the Roman notation). The practice is still observed by those who use the older calendars.

Folk traditions[edit]

In Ireland and Britain, it is a tradition that women may propose marriage only in leap years. While it has been claimed that the tradition was initiated by Saint Patrick or Brigid of Kildare in 5th century Ireland, this is dubious, as the tradition has not been attested before the 19th century.[27] Supposedly, a 1288 law by Queen Margaret of Scotland (then age five and living in Norway), required that fines be levied if a marriage proposal was refused by the man; compensation was deemed to be a pair of leather gloves, a single rose, £1, and a kiss.[citation needed][c] In some places the tradition was tightened to restricting female proposals to the modern leap day, February 29, or to the medieval (bissextile) leap day, February 24.[citation needed]

According to Felten: «A play from the turn of the 17th century, ‘The Maydes Metamorphosis,’ has it that ‘this is leape year/women wear breeches.’ A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn’t do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat – fair warning, if you will.»[28]

In Finland, the tradition is that if a man refuses a woman’s proposal on leap day, he should buy her the fabrics for a skirt.[29]

In France, since 1980, a satirical newspaper titled La Bougie du Sapeur is published only on leap year, on February 29.

In Greece, marriage in a leap year is considered unlucky.[30] One in five engaged couples in Greece will plan to avoid getting married in a leap year.[31]

In February 1988 the town of Anthony in Texas, declared itself «leap year capital of the world», and an international leapling birthday club was started.[32]

- 1908 postcards

-

Woman capturing man with butterfly-net

-

Women anxiously awaiting January 1

-

Histrionically preparing

Birthdays[edit]

A person born on February 29 may be called a «leapling» or a «leaper».[33] In common years, they usually celebrate their birthdays on February 28. In some situations, March 1 is used as the birthday in a non-leap year, since it is the day following February 28.

Technically, a leapling will have fewer birthday anniversaries than their age in years. This phenomenon may be exploited for dramatic effect when a person is declared to be only a quarter of their actual age, by counting their leap-year birthday anniversaries only. For example, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1879 comic opera The Pirates of Penzance, Frederic (the pirate apprentice) discovers that he is bound to serve the pirates until his 21st birthday (that is, when he turns 88 years old, since 1900 was not a leap year) rather than until his 21st year.

For legal purposes, legal birthdays depend on how local laws count time intervals

Baháʼí calendar[edit]

The Baháʼí calendar is a solar calendar composed of 19 months of 19 days each (361 days). Years begin at Naw-Rúz, on the vernal equinox, on or about March 21. A period of «Intercalary Days», called Ayyam-i-Ha, is inserted before the 19th month. This period normally has 4 days, but an extra day is added when needed to ensure that the following year starts on the vernal equinox. This is calculated and known years in advance.

Bengali, Indian and Thai calendars[edit]

The Revised Bengali Calendar of Bangladesh and the Indian National Calendar organise their leap years so that every leap day is close to February 29 in the Gregorian calendar and vice versa. This makes it easy to convert dates to or from Gregorian.

The Thai solar calendar uses the Buddhist Era (BE) but has been synchronized with the Gregorian since AD 1941.

Chinese calendar[edit]

The Chinese calendar is lunisolar, so a leap year has an extra month, often called an embolismic month after the Greek word for it. In the Chinese calendar, the leap month is added according to a rule which ensures that month 11 is always the month that contains the northern winter solstice. The intercalary month takes the same number as the preceding month; for example, if it follows the second month (二月) then it is simply called «leap second month» i.e. simplified Chinese: 闰二月; traditional Chinese: 閏二月; pinyin: rùn’èryuè.

Taiwan[edit]

![]()

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

The Civil Code of Taiwan since October 10, 1929,[34] implies that the legal birthday of a leapling is February 28 in common years:

If a period fixed by weeks, months, and years does not commence from the beginning of a week, month, or year, it ends with the ending of the day which precedes the day of the last week, month, or year which corresponds to that on which it began to commence. But if there is no corresponding day in the last month, the period ends with the ending of the last day of the last month.[35]

Hong Kong[edit]

Since 1990 non-retroactively, Hong Kong considers the legal birthday of a leapling March 1 in common years:[36]

- The time at which a person attains a particular age expressed in years shall be the commencement of the anniversary corresponding to the date of [their] birth.

- Where a person has been born on February 29 in a leap year, the relevant anniversary in any year other than a leap year shall be taken to be March 1.

- This section shall apply only where the relevant anniversary falls on a date after the date of commencement of this Ordinance.

Hebrew calendar[edit]

The Hebrew calendar is lunisolar with an embolismic month. This extra month is called Adar Rishon (first Adar) and is added before Adar, which then becomes Adar Sheini (second Adar). According to the Metonic cycle, this is done seven times every nineteen years (specifically, in years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 19). This is to ensure that Passover (Pesah) is always in the spring as required by the Torah (Pentateuch) in many verses[37] relating to Passover.

In addition, the Hebrew calendar has postponement rules that postpone the start of the year by one or two days. These postponement rules reduce the number of different combinations of year length and starting days of the week from 28 to 14, and regulate the location of certain religious holidays in relation to the Sabbath. In particular, the first day of the Hebrew year can never be Sunday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as «lo adu rosh» (לא אד״ו ראש), i.e., «Rosh [ha-Shanah, first day of the year] is not Sunday, Wednesday or Friday» (as the Hebrew word adu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Sunday, Wednesday and Friday). Accordingly, the first day of Passover is never Monday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as «lo badu Pesah» (לא בד״ו פסח), which has a double meaning — «Passover is not a legend», but also «Passover is not Monday, Wednesday or Friday» (as the Hebrew word badu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Monday, Wednesday and Friday).

One reason for this rule is that Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Hebrew calendar and the tenth day of the Hebrew year, now must never be adjacent to the weekly Sabbath (which is Saturday), i.e., it must never fall on Friday or Sunday, in order not to have two adjacent Sabbath days. However, Yom Kippur can still be on Saturday. A second reason is that Hoshana Rabbah, the 21st day of the Hebrew year, will never be on Saturday. These rules for the Feasts do not apply to the years from the Creation to the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt under Moses. It was at that time (cf. Exodus 13) that the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob gave the Hebrews their «Law» including the days to be kept holy and the feast days and Sabbaths.

Years consisting of 12 months have between 353 and 355 days. In a k’sidra («in order») 354-day year, months have alternating 30 and 29 day lengths. In a chaser («lacking») year, the month of Kislev is reduced to 29 days. In a malei («filled») year, the month of Marcheshvan is increased to 30 days. 13-month years follow the same pattern, with the addition of the 30-day Adar Alef, giving them between 383 and 385 days.

Islamic calendars[edit]

The observed and calculated versions of the lunar Islamic calendar do not have regular leap days, even though both have lunar months containing 29 or 30 days, generally in alternating order. However, the tabular Islamic calendar used by Islamic astronomers during the Middle Ages and still used by some Muslims does have a regular leap day added to the last month of the lunar year in 11 years of a 30-year cycle.[38] This additional day is found at the end of the last month, Dhu al-Hijjah, which is also the month of the Hajj.[39]

The Solar Hijri calendar is the modern Iranian calendar. It is an observational calendar that starts on the spring equinox (Northern Hemisphere) and adds a single intercalated day to the last month (Esfand) once every four or five years; the first leap year occurs as the fifth year of the typical 33-year cycle and the remaining leap years occur every four years through the remainder of the 33-year cycle. This system has less periodic deviation or jitter from its mean year than the Gregorian calendar and operates on the simple rule that its New Year’s Day must fall in the 24-hour period of vernal equinox .[40] The 33-year period is not completely regular; every so often the 33-year cycle will be broken by a cycle of 29 years.[41]

The Hijri-Shamsi calendar, also adopted by the Ahmadiyya Community, is based on solar calculations and is similar to the Gregorian calendar in its structure with the exception that its epoch is the Hijra.[42]

Julian, Coptic and Ethiopian calendars[edit]

The Julian calendar was instituted in 45 BC at the order of Julius Caesar, and the original intent was to make every fourth year a leap year, but this was not carried out correctly. Augustus ordered some leap years to be omitted to correct the problem, and by AD 8 the leap years were being observed every fourth year, and the observances were consistent up to and including modern times.

From AD 8 the Julian calendar received an extra day added to February in years that are multiples of 4 (although the AD year numbering system was not introduced until AD 525). This rule gives an average year length of 365.25 days. However, this is 11 minutes longer than a tropical year. This means that the calendar moves a day later than the Northern Hemisphere spring equinox about every 131 years.

The Coptic calendar has 13 months, 12 of 30 days each and one at the end of the year of 5 days, or 6 days in leap years. The Coptic Leap Year follows the same rules as the Julian Calendar so that the extra month always has six days in the year before a Julian Leap Year.[43] The Ethiopian calendar has twelve months of thirty days plus five or six epagomenal days, which comprise a thirteenth month.[44]

Revised Julian calendar[edit]

The Revised Julian calendar adds an extra day to February in years that are multiples of four, except for years that are multiples of 100 that do not leave a remainder of 200 or 600 when divided by 900. This rule agrees with the rule for the Gregorian calendar until 2799. The first year that dates in the Revised Julian calendar will not agree with those in the Gregorian calendar will be 2800, because it will be a leap year in the Gregorian calendar but not in the Revised Julian calendar.

This rule gives an average year length of 365.242222 days. This is a very good approximation to the mean tropical year, but because the vernal equinox year is slightly longer, the Revised Julian calendar, for the time being, does not do as good a job as the Gregorian calendar at keeping the vernal equinox on or close to March 21.

See also[edit]

- Century leap year

- Calendar reform includes proposals that have not (yet) been adopted.

- Leap second

- Leap week calendar

- Leap year bug

- Sansculottides

- Zeller’s congruence

- Leap year starting on Monday

- Leap year starting on Tuesday

- Leap year starting on Wednesday

- Leap year starting on Thursday

- Leap year starting on Friday

- Leap year starting on Saturday

- Leap year starting on Sunday

Notes[edit]

- ^ ‘Statute concerning [the] leap year and leap day’[19]

- ^ Though it appears in earlier Government proclamations, such as one of 1619.[22]

- ^ Virtually no laws of Margaret survive. Indeed, none concerning her subjects are recorded in the twelve-volume Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1814–75) covering the period 1124–1707 (two laws concerning young Margaret herself are recorded on pages 424 & 441–2 of volume I).

Sources[edit]

- Cheney, Christopher Robert, ed. (2000) [1945]. A Handbook of Dates for students of British History. Revised by Michael Jones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521778459.

- Pollard, A F (1940). «New Year’s Day and Leap Year in English History». The English Historical Review. 55 (218 (April 1940)): 177–193. JSTOR 553864.

References[edit]

- ^ Meeus, Jean (1998), Astronomical Algorithms, Willmann-Bell, p. 62

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2012), «leap year», Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ «leap year». Oxford US Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ «Astronomical almanac online glossary». US Naval Observatory. 2020.

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M. (2008). Calendrical calculations (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-88540-9. OCLC 144768713.

The calendar in use today in most of the world is the Gregorian or ‘new-style’ calendar designed by a commission assembled by Pope Gregory XIII in the sixteenth century.

- ^ Lerner, Ed. K. Lee; Lerner, Brenda W. (2004). «Calendar». The Gale Encyclopedia of Science. Detroit, MI: Gale.

- ^ Introduction to Calendars Archived 2019-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. (10 August 2017). United States Naval Observatory.

- ^ United States Naval Observatory (June 14, 2011), Leap Years, archived from the original on October 15, 2007, retrieved April 9, 2014

- ^ Lerner & Lerner 2004, p. 681.

- ^ Richards, E. G. (2013), «Calendars», in Urban, S. E.; Seidelmann, P. K. (eds.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (3rd ed.), Mill Valley CA: University Science Books, p. 598, ISBN 9781891389856

- ^ Doggett, L.E. (1992), «Calendars», in Seidelmann, P. K. (ed.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (2nd ed.), Sausalito, CA: University Science Books, pp. 580–1

- ^ Richards, E. G. (1998), Mapping time: The Calendar and its History, Oxford University Press, pp. 250–1, ISBN 0-19-286205-7

- ^ a b c Pollard (1940), p. 188.

- ^ Cheney (2000).

- ^ According to Christian Ludwig Ideler (1825)

- ^ Key, Thomas Hewitt (2013) [1875], Calendarium, University of Chicago,

the intermediate days are in all cases reckoned backwards upon the Roman principle already explained of counting both extremes.

- ^ Pollard (1940), p. 186.

- ^ a b Cheney (2000), Page 145, Footnote 1.

- ^ a b Ruffhead, Owen (1763). The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the End of the Last Parliament. Mark Basket. p. 20. Retrieved 21 October 2021. (21 Hen, III)

- ^ Edward Coke (1628). «Cap. 1, Of Fee Simple.«. First Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England. p. 8 left [30].

- ^ Pickering, Danby, ed. (1765). The Statutes at Large: from the 23rd to the 26th Year of King George II. Vol. 20. Cambridge: Charles Bathurst. p. 194. Retrieved 28 January 2020. (calendar at the end of the Act)

- ^ Bond, John James (1875). «Preface». Handy Book of Rules and Tables for Verifying Dates With the Christian Era Giving an Account of the Chief Eras and Systems Used by Various Nations…’ (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. xix.

- ^ Campion, Rev W M; Beamont, Rev W J (1870). The Prayer Book interleaved. London. p. 31 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Church of England (1762) [1662]. Book of Common Prayer. Cambridge: John Baskerville – via Archive.org.

- ^ Cheney (2000), p. 8.

- ^ Liber Extra, 5. 40. 14. 1

- ^ Mikkelson, B.; Mikkelson, D.P. (2010), «The Privilege of Ladies», The Urban Legends Reference Pages, snopes.com

- ^ Felten, E. (February 23, 2008), «The Bissextile Beverage», Wall Street Journal

- ^ Hallett, S. (February 29, 2012), «Leap Year Proposal: What’s The Story Behind It?», Huffington Post, retrieved December 21, 2015

- ^ «A Greek Wedding», Anagnosis Books, retrieved January 12, 2012

- ^ «Teaching Tips 63», Developing Teachers, retrieved January 12, 2012

- ^ Anthony – Leap Year Capital of the World, Time and Date, 2008, retrieved 6 November 2011

- ^ «February 29: 29 things you need to know about leap years and their extra day», Mirror, February 28, 2012, retrieved December 7, 2015

- ^ Legislative History of the Civil Code of the Republic of China

- ^ «Article 121 Civil Code», Part I General Principles of the Republic of China

- ^ Age of Majority (Related Provisions) Ordinance (Ch. 410 Sec. 5), Hong Kong Department of Justice, June 30, 1997 (Enacted in 1990).

- ^ Exodus 23:15, Exodus 34:18, Deuteronomy 15:1, Deuteronomy 15:13

- ^ The Islamic leap year, Time and Date AS, n.d., retrieved February 29, 2012

- ^ Leap year trivia you might want to know, GMA News, n.d., retrieved February 29, 2012

- ^ Bromberg, Irv, Fixed Arithmetic Calendar Cycle Jitter, University of Toronto

- ^ Heydari-Malayeri, M. (2004), A Concise Review of the Iranian Calendar, Paris Observatory, arXiv:astro-ph/0409620, Bibcode:2004astro.ph..9620H

- ^ Hijri-Shamsi Calendar, Al Islam, 2015, retrieved April 18, 2015,

The time frame in these months is the same as […] the months of a Christian calendar.

- ^ Fr Tadros Y Malaty (1988). The Coptic Calendar and Church of Alexandria (Report). The Monastery of St. Macarius Press, The Desert of Scete. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Ethiopia: The country where a year lasts 13 months». BBC News. 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

External links[edit]

- Gray, Meghan. «29 Leap Year». Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Famous Leapers

- Leap Day Campaign: Galileo Day

- History Behind Leap Year National Geographic Society

A leap year (also known as an intercalary year or bissextile year) is a calendar year that contains an additional day (or, in the case of a lunisolar calendar, a month) added to keep the calendar year synchronized with the astronomical year or seasonal year.[1] Because astronomical events and seasons do not repeat in a whole number of days, calendars that have a constant number of days in each year will unavoidably drift over time with respect to the event that the year is supposed to track, such as seasons. By inserting (called intercalating in technical terminology) an additional day or month into some years, the drift between a civilization’s dating system and the physical properties of the Solar System can be corrected. A year that is not a leap year is a common year.

For example, in the Gregorian calendar, each leap year has 366 days instead of 365, by extending February to 29 days rather than the common 28. These extra days occur in each year that is an integer multiple of 4 (except for years evenly divisible by 100, but not by 400). The leap year of 366 days has 52 weeks and two days, hence the year following a leap year will start later by two days of the week.

In the lunisolar Hebrew calendar, Adar Aleph, a 13th lunar month, is added seven times every 19 years to the twelve lunar months in its common years to keep its calendar year from drifting through the seasons. In the Bahá’í Calendar, a leap day is added when needed to ensure that the following year begins on the March equinox.

The term leap year probably comes from the fact that a fixed date in the Gregorian calendar normally advances one day of the week from one year to the next, but the day of the week in the 12 months following the leap day (from March 1 through February 28 of the following year) will advance two days due to the extra day, thus leaping over one day in the week.[2][3] For example, Christmas Day (December 25) fell on a Sunday in 2016, Monday in 2017, Tuesday in 2018, and Wednesday in 2019, but then leapt over Thursday to fall on a Friday in 2020.

The length of a day is also occasionally corrected by inserting a leap second into Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) because of variations in Earth’s rotation period. Unlike leap days, leap seconds are not introduced on a regular schedule because variations in the length of the day are not entirely predictable.

Leap years can present a problem in computing, known as the leap year bug, when a year is not correctly identified as a leap year or when February 29 is not handled correctly in logic that accepts or manipulates dates.

Julian calendar[edit]

On 1 January 45 BC, by edict, Julius Caesar reformed the historic Roman calendar to make it a consistent solar calendar (rather than one which was neither strictly lunar nor strictly solar), thus removing the need for frequent intercalary months. His rule for leap years was a simple one: add a leap day every four years. This algorithm is close to reality: a Julian year lasts 365.25 days, a mean tropical year about 365.2422 days.[4] Consequently, even this Julian calendar drifts out of ‘true’ by about three days every 400 years. The Julian calendar continued in use unaltered for about 1600 years until the Catholic Church became concerned about the widening divergence between the March Equinox and 21 March, as explained at Gregorian calendar, below.

Gregorian calendar[edit]

An image showing which century years are leap years in the Gregorian calendar

In the Gregorian calendar, the standard calendar in most of the world,[5] most years that are multiples of 4 are leap years. In each leap year, the month of February has 29 days instead of 28. Adding one extra day in the calendar every four years compensates for the fact that a period of 365 days is shorter than a tropical year by almost 6 hours.[6] Some exceptions to this basic rule are required since the duration of a tropical year is slightly less than 365.25 days. The Gregorian reform modified the Julian calendar’s scheme of leap years as follows:

Every year that is exactly divisible by four is a leap year, except for years that are exactly divisible by 100, but these centurial years are leap years if they are exactly divisible by 400. For example, the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not leap years, but the years 1600 and 2000 are.[7]

Over a period of four centuries, the accumulated error of adding a leap day every four years amounts to about three extra days. The Gregorian calendar therefore omits three leap days every 400 years, which is the length of its leap cycle. This is done by omitting February 29 in the three century years (multiples of 100) that are not multiples of 400.[8][9] The years 2000 and 2400 are leap years, but not 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200 and 2300. By this rule, an entire leap cycle is 400 years which total 146,097 days, and the average number of days per year is 365 + 1⁄4 − 1⁄100 + 1⁄400 = 365 + 97⁄400 = 365.2425.[10] (This rule could be applied to years before the Gregorian reform to create a proleptic Gregorian calendar,[11] though the result would not match any historical records.

This graph shows the variations in date and time of the June Solstice due to unequally spaced «leap day» rules. Contrast this with the Iranian Solar Hijri calendar, which generally has 8 leap year days every 33 years.

The Gregorian calendar was designed to keep the vernal equinox on or close to March 21, so that the date of Easter (celebrated on the Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon that falls on or after March 21) remains close to the vernal equinox.[12] The «Accuracy» section of the «Gregorian calendar» article discusses how well the Gregorian calendar achieves this design goal, and how well it approximates the tropical year.

Leap day in the Julian and Gregorian calendars [edit]

A Swedish pocket calendar from 2008 showing February 29

February 1900 calendar showing that 1900 was not a leap year

The intercalary day that usually occurs every four years is called the leap day and is created by adding an extra day to February. This day is added to the calendar in leap years as a corrective measure because the Earth does not orbit the Sun in precisely 365 days. Since about the fifteenth century, this extra day is February 29, but when the Julian calendar was introduced, leap day was handled differently in two respects. First, leap day fell within February and not at the end: February 24 was doubled to create the (strange to modern eyes) two days both dated February 24.[13] Second, the leap day was simply not counted so that a leap year still had 365 days.[14][page needed]

Early Roman practice[edit]

The early Roman calendar was a lunisolar one that consisted of 12 months, for a total of 355 days. In addition, a 27- or 28-day intercalary month, the Mensis Intercalaris, was sometimes inserted into February, at the first or second day after the Terminalia a. d. VII Kal. Mar., (February 23), to resynchronise the lunar and solar cycles. The remaining days of Februarius were discarded. This intercalary month, named Intercalaris or Mercedonius, contained 27 days. The religious festivals that were normally celebrated in the last five days of February were moved to the last five days of Intercalaris. The lunisolar calendar was abandoned about 450 BC by the decemviri,[15] who implemented the Roman Republican calendar, used until 46 BC. The days of these calendars were counted down (inclusively) to the next named day, so February 24 was ante diem sextum Kalendas Martias [«the sixth day before the calends of March»] often abbreviated a. d. VI Kal. Mart. The Romans counted days inclusively in their calendars, so this was actually the fifth day before March 1 when counted in the modern exclusive manner (i.e., not including both the starting and ending day).[16] Because only 22 or 23 days were effectively added, not a full lunation, the calends and ides of the Roman Republican calendar were no longer associated with the new moon and full moon.

Julian reform[edit]

In Caesar’s revised calendar, there was just one intercalary day – nowadays called the leap day – to be inserted every fourth year and this too was done after 23 of February. To create the intercalary day, the existing ante diem sextum Kalendas Martias ([sixth day before the Kalends (first day) of March], February 24) was doubled,[17] producing ante diem bis sextum Kalendas Martias [a second sixth day before the Kalends (first day) of March]. This bis sextum [«twice sixth»] was translated as ‘bissextile’: the ‘bissextile day’ is the leap day and a ‘bissextile year’ is a year which includes a leap day.[18] This second instance of the sixth day before the Kalends of March was inserted in calendars between the ‘normal’ fifth and sixth days. By a legal fiction, the Romans treated both the first «sixth day» and the additional «sixth day» before the Kalends of March as one day. Thus a child born on either of those days in a leap year would have its first birthday on the following sixth day before the Kalends of March. In a leap year in the original Julian calendar, there were indeed two days both numbered 24 February. This practice continued for another fifteen to seventeen centuries, even after most countries had adopted the Gregorian calendar.

For legal purposes, the two days of the bis sextum were considered to be a single day, with the second sixth being intercalated; but in common practice by 238, when Censorinus wrote, the intercalary day was followed by the last five days of February, a. d. VI, V, IV, III and pridie Kal. Mart. (the days numbered 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28 from the beginning of February in a common year), so that the intercalated day was the first of the doubled pair. Thus the intercalated day was effectively inserted between the 23rd and 24th days of February. All later writers, including Macrobius about 430, Bede in 725, and other medieval computists (calculators of Easter), continued to state that the bissextum (bissextile day) occurred before the last five days of February.[citation needed]

In England, the Church and civil society continued the Roman practice whereby the leap day was simply not counted so that a leap year was only reckoned as 365 days. Henry III’s 1236 Statute De Anno et Die Bissextili[a] instructed magistrates to treat the leap day and the day before as one day.[19][18] The practical application of the rule is obscure. It was regarded as in force in the time of the famous lawyer Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) because he cites it in his Institutes of the Lawes of England. However, Coke merely quotes the act with a short translation and does not give practical examples.[20]

‘ … and by (b) the statute de anno bissextili, it is provided, quod computentur dies ille excrescens et dies proxime præcedens pro unico dii, so as in computation that day excrescent is not accounted.’

29 February[edit]

Replacement (by 29 February) of the awkward practice of having two days with the same date appears to have evolved by custom and practice, the etymological origin of the term «bissextile» seeming to have been lost.[13] In England in the course of the fifteenth century, «29 February» appears increasingly often in legal documents – although the records of the proceedings of the House of Commons of England continued to use the old system until the middle of the sixteenth century.[13] It was not until passage of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 that 29 February was formally recognised in British law.[21][b]

Liturgical practices[edit]

In the older Roman Missal, feast days falling on or after February 24 are celebrated one day later in a leap year.

In the liturgical calendar of the Christian churches, the placement of the leap day is significant because of the date of the feast of Saint Matthias, which is defined as the sixth day before March 1 (counting inclusively). The Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer was still using the «two days with the same date» system in its 1542 edition;[23] it first included a calendar which used entirely consecutive day counting from 1662 and showed leap day as falling on 29 February.[24] In the 1680s, the Church of England declared 25 February to be the feast of St Matthias.[25]

Until 1970, the Roman Catholic Church always celebrated the feast of Saint Matthias on a. d. VI Kal. Mart., so if the days were numbered from the beginning of the month, it was named February 24 in common years, but the presence of the bissextum in a bissextile year immediately before a. d. VI Kal. Mart. shifted the latter day to February 25 in leap years, with the Vigil of St. Matthias shifting from February 23 to the leap day of February 24. This shift did not take place in pre-Reformation Norway and Iceland; Pope Alexander III ruled that either practice was lawful.[26] Other feasts normally falling on February 25–28 in common years are also shifted to the following day in a leap year (although they would be on the same day according to the Roman notation). The practice is still observed by those who use the older calendars.

Folk traditions[edit]

In Ireland and Britain, it is a tradition that women may propose marriage only in leap years. While it has been claimed that the tradition was initiated by Saint Patrick or Brigid of Kildare in 5th century Ireland, this is dubious, as the tradition has not been attested before the 19th century.[27] Supposedly, a 1288 law by Queen Margaret of Scotland (then age five and living in Norway), required that fines be levied if a marriage proposal was refused by the man; compensation was deemed to be a pair of leather gloves, a single rose, £1, and a kiss.[citation needed][c] In some places the tradition was tightened to restricting female proposals to the modern leap day, February 29, or to the medieval (bissextile) leap day, February 24.[citation needed]

According to Felten: «A play from the turn of the 17th century, ‘The Maydes Metamorphosis,’ has it that ‘this is leape year/women wear breeches.’ A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn’t do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat – fair warning, if you will.»[28]

In Finland, the tradition is that if a man refuses a woman’s proposal on leap day, he should buy her the fabrics for a skirt.[29]

In France, since 1980, a satirical newspaper titled La Bougie du Sapeur is published only on leap year, on February 29.

In Greece, marriage in a leap year is considered unlucky.[30] One in five engaged couples in Greece will plan to avoid getting married in a leap year.[31]

In February 1988 the town of Anthony in Texas, declared itself «leap year capital of the world», and an international leapling birthday club was started.[32]

- 1908 postcards

-

Woman capturing man with butterfly-net

-

Women anxiously awaiting January 1

-

Histrionically preparing

Birthdays[edit]

A person born on February 29 may be called a «leapling» or a «leaper».[33] In common years, they usually celebrate their birthdays on February 28. In some situations, March 1 is used as the birthday in a non-leap year, since it is the day following February 28.

Technically, a leapling will have fewer birthday anniversaries than their age in years. This phenomenon may be exploited for dramatic effect when a person is declared to be only a quarter of their actual age, by counting their leap-year birthday anniversaries only. For example, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1879 comic opera The Pirates of Penzance, Frederic (the pirate apprentice) discovers that he is bound to serve the pirates until his 21st birthday (that is, when he turns 88 years old, since 1900 was not a leap year) rather than until his 21st year.

For legal purposes, legal birthdays depend on how local laws count time intervals

Baháʼí calendar[edit]

The Baháʼí calendar is a solar calendar composed of 19 months of 19 days each (361 days). Years begin at Naw-Rúz, on the vernal equinox, on or about March 21. A period of «Intercalary Days», called Ayyam-i-Ha, is inserted before the 19th month. This period normally has 4 days, but an extra day is added when needed to ensure that the following year starts on the vernal equinox. This is calculated and known years in advance.

Bengali, Indian and Thai calendars[edit]

The Revised Bengali Calendar of Bangladesh and the Indian National Calendar organise their leap years so that every leap day is close to February 29 in the Gregorian calendar and vice versa. This makes it easy to convert dates to or from Gregorian.

The Thai solar calendar uses the Buddhist Era (BE) but has been synchronized with the Gregorian since AD 1941.

Chinese calendar[edit]

The Chinese calendar is lunisolar, so a leap year has an extra month, often called an embolismic month after the Greek word for it. In the Chinese calendar, the leap month is added according to a rule which ensures that month 11 is always the month that contains the northern winter solstice. The intercalary month takes the same number as the preceding month; for example, if it follows the second month (二月) then it is simply called «leap second month» i.e. simplified Chinese: 闰二月; traditional Chinese: 閏二月; pinyin: rùn’èryuè.

Taiwan[edit]

![]()

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

The Civil Code of Taiwan since October 10, 1929,[34] implies that the legal birthday of a leapling is February 28 in common years:

If a period fixed by weeks, months, and years does not commence from the beginning of a week, month, or year, it ends with the ending of the day which precedes the day of the last week, month, or year which corresponds to that on which it began to commence. But if there is no corresponding day in the last month, the period ends with the ending of the last day of the last month.[35]

Hong Kong[edit]

Since 1990 non-retroactively, Hong Kong considers the legal birthday of a leapling March 1 in common years:[36]

- The time at which a person attains a particular age expressed in years shall be the commencement of the anniversary corresponding to the date of [their] birth.

- Where a person has been born on February 29 in a leap year, the relevant anniversary in any year other than a leap year shall be taken to be March 1.

- This section shall apply only where the relevant anniversary falls on a date after the date of commencement of this Ordinance.

Hebrew calendar[edit]

The Hebrew calendar is lunisolar with an embolismic month. This extra month is called Adar Rishon (first Adar) and is added before Adar, which then becomes Adar Sheini (second Adar). According to the Metonic cycle, this is done seven times every nineteen years (specifically, in years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 19). This is to ensure that Passover (Pesah) is always in the spring as required by the Torah (Pentateuch) in many verses[37] relating to Passover.

In addition, the Hebrew calendar has postponement rules that postpone the start of the year by one or two days. These postponement rules reduce the number of different combinations of year length and starting days of the week from 28 to 14, and regulate the location of certain religious holidays in relation to the Sabbath. In particular, the first day of the Hebrew year can never be Sunday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as «lo adu rosh» (לא אד״ו ראש), i.e., «Rosh [ha-Shanah, first day of the year] is not Sunday, Wednesday or Friday» (as the Hebrew word adu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Sunday, Wednesday and Friday). Accordingly, the first day of Passover is never Monday, Wednesday or Friday. This rule is known in Hebrew as «lo badu Pesah» (לא בד״ו פסח), which has a double meaning — «Passover is not a legend», but also «Passover is not Monday, Wednesday or Friday» (as the Hebrew word badu is written by three Hebrew letters signifying Monday, Wednesday and Friday).

One reason for this rule is that Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Hebrew calendar and the tenth day of the Hebrew year, now must never be adjacent to the weekly Sabbath (which is Saturday), i.e., it must never fall on Friday or Sunday, in order not to have two adjacent Sabbath days. However, Yom Kippur can still be on Saturday. A second reason is that Hoshana Rabbah, the 21st day of the Hebrew year, will never be on Saturday. These rules for the Feasts do not apply to the years from the Creation to the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt under Moses. It was at that time (cf. Exodus 13) that the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob gave the Hebrews their «Law» including the days to be kept holy and the feast days and Sabbaths.

Years consisting of 12 months have between 353 and 355 days. In a k’sidra («in order») 354-day year, months have alternating 30 and 29 day lengths. In a chaser («lacking») year, the month of Kislev is reduced to 29 days. In a malei («filled») year, the month of Marcheshvan is increased to 30 days. 13-month years follow the same pattern, with the addition of the 30-day Adar Alef, giving them between 383 and 385 days.

Islamic calendars[edit]

The observed and calculated versions of the lunar Islamic calendar do not have regular leap days, even though both have lunar months containing 29 or 30 days, generally in alternating order. However, the tabular Islamic calendar used by Islamic astronomers during the Middle Ages and still used by some Muslims does have a regular leap day added to the last month of the lunar year in 11 years of a 30-year cycle.[38] This additional day is found at the end of the last month, Dhu al-Hijjah, which is also the month of the Hajj.[39]

The Solar Hijri calendar is the modern Iranian calendar. It is an observational calendar that starts on the spring equinox (Northern Hemisphere) and adds a single intercalated day to the last month (Esfand) once every four or five years; the first leap year occurs as the fifth year of the typical 33-year cycle and the remaining leap years occur every four years through the remainder of the 33-year cycle. This system has less periodic deviation or jitter from its mean year than the Gregorian calendar and operates on the simple rule that its New Year’s Day must fall in the 24-hour period of vernal equinox .[40] The 33-year period is not completely regular; every so often the 33-year cycle will be broken by a cycle of 29 years.[41]

The Hijri-Shamsi calendar, also adopted by the Ahmadiyya Community, is based on solar calculations and is similar to the Gregorian calendar in its structure with the exception that its epoch is the Hijra.[42]

Julian, Coptic and Ethiopian calendars[edit]

The Julian calendar was instituted in 45 BC at the order of Julius Caesar, and the original intent was to make every fourth year a leap year, but this was not carried out correctly. Augustus ordered some leap years to be omitted to correct the problem, and by AD 8 the leap years were being observed every fourth year, and the observances were consistent up to and including modern times.

From AD 8 the Julian calendar received an extra day added to February in years that are multiples of 4 (although the AD year numbering system was not introduced until AD 525). This rule gives an average year length of 365.25 days. However, this is 11 minutes longer than a tropical year. This means that the calendar moves a day later than the Northern Hemisphere spring equinox about every 131 years.

The Coptic calendar has 13 months, 12 of 30 days each and one at the end of the year of 5 days, or 6 days in leap years. The Coptic Leap Year follows the same rules as the Julian Calendar so that the extra month always has six days in the year before a Julian Leap Year.[43] The Ethiopian calendar has twelve months of thirty days plus five or six epagomenal days, which comprise a thirteenth month.[44]

Revised Julian calendar[edit]

The Revised Julian calendar adds an extra day to February in years that are multiples of four, except for years that are multiples of 100 that do not leave a remainder of 200 or 600 when divided by 900. This rule agrees with the rule for the Gregorian calendar until 2799. The first year that dates in the Revised Julian calendar will not agree with those in the Gregorian calendar will be 2800, because it will be a leap year in the Gregorian calendar but not in the Revised Julian calendar.

This rule gives an average year length of 365.242222 days. This is a very good approximation to the mean tropical year, but because the vernal equinox year is slightly longer, the Revised Julian calendar, for the time being, does not do as good a job as the Gregorian calendar at keeping the vernal equinox on or close to March 21.

See also[edit]

- Century leap year

- Calendar reform includes proposals that have not (yet) been adopted.

- Leap second

- Leap week calendar

- Leap year bug

- Sansculottides

- Zeller’s congruence

- Leap year starting on Monday

- Leap year starting on Tuesday

- Leap year starting on Wednesday

- Leap year starting on Thursday

- Leap year starting on Friday

- Leap year starting on Saturday

- Leap year starting on Sunday

Notes[edit]

- ^ ‘Statute concerning [the] leap year and leap day’[19]

- ^ Though it appears in earlier Government proclamations, such as one of 1619.[22]

- ^ Virtually no laws of Margaret survive. Indeed, none concerning her subjects are recorded in the twelve-volume Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland (1814–75) covering the period 1124–1707 (two laws concerning young Margaret herself are recorded on pages 424 & 441–2 of volume I).

Sources[edit]

- Cheney, Christopher Robert, ed. (2000) [1945]. A Handbook of Dates for students of British History. Revised by Michael Jones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521778459.

- Pollard, A F (1940). «New Year’s Day and Leap Year in English History». The English Historical Review. 55 (218 (April 1940)): 177–193. JSTOR 553864.

References[edit]

- ^ Meeus, Jean (1998), Astronomical Algorithms, Willmann-Bell, p. 62

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2012), «leap year», Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ «leap year». Oxford US Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ «Astronomical almanac online glossary». US Naval Observatory. 2020.

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M. (2008). Calendrical calculations (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-88540-9. OCLC 144768713.

The calendar in use today in most of the world is the Gregorian or ‘new-style’ calendar designed by a commission assembled by Pope Gregory XIII in the sixteenth century.

- ^ Lerner, Ed. K. Lee; Lerner, Brenda W. (2004). «Calendar». The Gale Encyclopedia of Science. Detroit, MI: Gale.

- ^ Introduction to Calendars Archived 2019-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. (10 August 2017). United States Naval Observatory.

- ^ United States Naval Observatory (June 14, 2011), Leap Years, archived from the original on October 15, 2007, retrieved April 9, 2014

- ^ Lerner & Lerner 2004, p. 681.

- ^ Richards, E. G. (2013), «Calendars», in Urban, S. E.; Seidelmann, P. K. (eds.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (3rd ed.), Mill Valley CA: University Science Books, p. 598, ISBN 9781891389856

- ^ Doggett, L.E. (1992), «Calendars», in Seidelmann, P. K. (ed.), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (2nd ed.), Sausalito, CA: University Science Books, pp. 580–1

- ^ Richards, E. G. (1998), Mapping time: The Calendar and its History, Oxford University Press, pp. 250–1, ISBN 0-19-286205-7

- ^ a b c Pollard (1940), p. 188.

- ^ Cheney (2000).

- ^ According to Christian Ludwig Ideler (1825)

- ^ Key, Thomas Hewitt (2013) [1875], Calendarium, University of Chicago,

the intermediate days are in all cases reckoned backwards upon the Roman principle already explained of counting both extremes.

- ^ Pollard (1940), p. 186.

- ^ a b Cheney (2000), Page 145, Footnote 1.

- ^ a b Ruffhead, Owen (1763). The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the End of the Last Parliament. Mark Basket. p. 20. Retrieved 21 October 2021. (21 Hen, III)

- ^ Edward Coke (1628). «Cap. 1, Of Fee Simple.«. First Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England. p. 8 left [30].

- ^ Pickering, Danby, ed. (1765). The Statutes at Large: from the 23rd to the 26th Year of King George II. Vol. 20. Cambridge: Charles Bathurst. p. 194. Retrieved 28 January 2020. (calendar at the end of the Act)

- ^ Bond, John James (1875). «Preface». Handy Book of Rules and Tables for Verifying Dates With the Christian Era Giving an Account of the Chief Eras and Systems Used by Various Nations…’ (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. xix.

- ^ Campion, Rev W M; Beamont, Rev W J (1870). The Prayer Book interleaved. London. p. 31 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Church of England (1762) [1662]. Book of Common Prayer. Cambridge: John Baskerville – via Archive.org.

- ^ Cheney (2000), p. 8.

- ^ Liber Extra, 5. 40. 14. 1

- ^ Mikkelson, B.; Mikkelson, D.P. (2010), «The Privilege of Ladies», The Urban Legends Reference Pages, snopes.com

- ^ Felten, E. (February 23, 2008), «The Bissextile Beverage», Wall Street Journal

- ^ Hallett, S. (February 29, 2012), «Leap Year Proposal: What’s The Story Behind It?», Huffington Post, retrieved December 21, 2015

- ^ «A Greek Wedding», Anagnosis Books, retrieved January 12, 2012

- ^ «Teaching Tips 63», Developing Teachers, retrieved January 12, 2012

- ^ Anthony – Leap Year Capital of the World, Time and Date, 2008, retrieved 6 November 2011

- ^ «February 29: 29 things you need to know about leap years and their extra day», Mirror, February 28, 2012, retrieved December 7, 2015

- ^ Legislative History of the Civil Code of the Republic of China

- ^ «Article 121 Civil Code», Part I General Principles of the Republic of China

- ^ Age of Majority (Related Provisions) Ordinance (Ch. 410 Sec. 5), Hong Kong Department of Justice, June 30, 1997 (Enacted in 1990).

- ^ Exodus 23:15, Exodus 34:18, Deuteronomy 15:1, Deuteronomy 15:13

- ^ The Islamic leap year, Time and Date AS, n.d., retrieved February 29, 2012

- ^ Leap year trivia you might want to know, GMA News, n.d., retrieved February 29, 2012

- ^ Bromberg, Irv, Fixed Arithmetic Calendar Cycle Jitter, University of Toronto

- ^ Heydari-Malayeri, M. (2004), A Concise Review of the Iranian Calendar, Paris Observatory, arXiv:astro-ph/0409620, Bibcode:2004astro.ph..9620H

- ^ Hijri-Shamsi Calendar, Al Islam, 2015, retrieved April 18, 2015,

The time frame in these months is the same as […] the months of a Christian calendar.

- ^ Fr Tadros Y Malaty (1988). The Coptic Calendar and Church of Alexandria (Report). The Monastery of St. Macarius Press, The Desert of Scete. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ «Ethiopia: The country where a year lasts 13 months». BBC News. 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

External links[edit]

- Gray, Meghan. «29 Leap Year». Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Famous Leapers

- Leap Day Campaign: Galileo Day

- History Behind Leap Year National Geographic Society

|

| Проверить информацию. Необходимо проверить точность фактов и достоверность сведений, изложенных в этой статье. |

Високо́сный год (лат. bis sextus — «второй шестой») — год в юлианском и григорианском календарях, продолжительность которого равна 366 дням — на одни сутки больше продолжительности обычного, невисокосного года. В юлианском календаре високосным годом является каждый четвёртый год, в григорианском календаре из этого правила есть исключения.

История введения

С 1 января 45 года до н. э. римский диктатор Гай Юлий Цезарь ввёл календарь, разработанный александрийскими астрономами во главе с Созигеном, который был основан на том, что астрономический год примерно равен 365,25 суток (365 суток и 6 часов). Этот календарь был назван юлианским. Для того, чтобы выровнять шестичасовое смещение, был введён високосный год. Три года считалось по 365 суток, а в каждый год, кратный четырём, добавлялись одни дополнительные сутки в феврале.

В римском календаре дни считались по отношению к последующим календам (первый день месяца), нонам (5-й или 7-й день) и идам (13-й или 15-й день месяца). Так, день 24 февраля обозначался как ante diem sextum calendas martii («шестой день перед мартовскими календами»). Цезарь постановил добавлять к февралю второй шестой (bis sextus) день перед мартовскими календами, то есть второй день 24 февраля. Февраль был выбран как последний месяц римского года. Первым високосным годом стал 45 до н. э.

Цезарь был убит через два года после введения нового календаря, второй високосный год начался уже после его смерти. Возможно, этим объясняется тот факт, что жрецы, отвечавшие за функционирование календаря, не поняли принцип введения добавочного дня каждый четвёртый год, и вместо этого стали вводить добавочный день в феврале каждые три года (предполагается, что они отсчитывали четвёртый от года, предшествующего високосному). В течение 36 лет после Цезаря високосным был каждый третий год, и лишь затем император Август восстановил правильный порядок следования високосных лет (а также отменил несколько последующих високосных лет, чтобы убрать накопившийся добавочный сдвиг). Из сопоставления римских и египетских датировок в папирусе, найденном в 1999 году[источник не указан 764 дня], было установлено, что високосными годами в Риме были 44, 41, 38, 35, 32, 29, 26, 23, 20, 17, 14, 11, 8 годы до н. э., 4, 8, 12 и в последующем каждый четвёртый год.

Григорианский календарь

Продолжительность тропического года (время между двумя весенними равноденствиями) составляет 365 суток 5 часов 48 минут 46 секунд. Различие в продолжительности тропического года и среднего юлианского календарного года (365,25 суток) составляет 11 минут 14 секунд. Из этих 11 минут и 14 секунд приблизительно за 128 лет складываются одни сутки.

По истечении столетий было замечено смещение дня весеннего равноденствия, с которым связаны церковные праздники. К XVI веку весеннее равноденствие наступало примерно на 10 суток раньше 21 марта, используемого для определения дня Пасхи.

Чтобы компенсировать накопившуюся ошибку и избежать подобного смещения в будущем, в 1582 году римский папа Григорий XIII провёл реформу календаря. Чтобы средний календарный год лучше соответствовал солнечному, было решено изменить правило високосных лет. По-прежнему високосным оставался год, номер которого кратен четырём, но исключение делалось для тех, которые были кратны 100. Отныне такие годы были високосными только тогда, когда делились ещё и на 400.

Иными словами, год является високосным в двух случаях: либо он кратен 4, но при этом не кратен 100, либо кратен 400. Год не является високосным, если он не кратен 4, либо он кратен 100, но при этом не кратен 400.

Последние годы столетий, оканчивающиеся на два нуля, в трёх случаях из четырёх не являются високосными. Так, годы 1700, 1800 и 1900 не являются високосными, так как они кратны 100 и не кратны 400. Годы 1600 и 2000 — високосные, так как они кратны 400. Годы 2100, 2200 и 2300 — невисокосные. В високосные годы вводится дополнительный день — 29 февраля.

Еврейский календарь

В еврейском календаре високосным годом называют год, к которому добавляют месяц, а не день. Причина этого в том, что еврейский календарь основывается на лунном месяце, и поэтому год из двенадцати месяцев отстает от астрономического солнечного года примерно на 11 дней. Для приравнивания лунных лет к солнечному году введен високосный год из тринадцати месяцев. В 19-летний цикл входят 12 простых и 7 високосных лет.

См. также

- 29 февраля

- 30 февраля

- Юлианский календарь

- Григорианский календарь

- Новоюлианский календарь

- Високосная секунда

- Еврейский календарь

|

| В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации. Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%92%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B9_%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B4

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Високосный год (значения).

Високо́сный год (от лат. bis sextus — «второй шестой»[1][2][3]) — год в юлианском и григорианском календарях, продолжительность которого равна 366 дням — на одни сутки больше продолжительности обычного, невисокосного года. В юлианском календаре високосным годом является каждый четвёртый год, в григорианском календаре из этого правила есть исключения.

История введения

С 1 января 45 года до н. э. римский диктатор Гай Юлий Цезарь ввёл календарь, разработанный александрийскими астрономами во главе с Созигеном, который был основан на том, что астрономический год примерно равен 365,25 суток (365 суток и 6 часов). Этот календарь был назван юлианским. Для того чтобы выровнять шестичасовое смещение, был введён високосный год. Три года считалось по 365 суток, а в каждый год, кратный четырём, добавлялись одни дополнительные сутки в феврале.[4]

В римском календаре дни считались по отношению к последующим календам (первый день месяца), нонам (5-й или 7-й день) и идам (13-й или 15-й день месяца). Так, день 24 февраля обозначался как ante diem sextum calendas martii («шестой день перед мартовскими календами»). Цезарь постановил добавлять к февралю второй шестой (bis sextus) день перед мартовскими календами, то есть второй день 24 февраля. Февраль был выбран как последний месяц римского года. Первым високосным годом стал 45 год до н. э.

Цезарь был убит через два года после введения нового календаря, второй високосный год начался уже после его смерти. Возможно, этим объясняется тот факт, что жрецы, отвечавшие за функционирование календаря, не поняли принцип введения добавочного дня каждый четвёртый год, и вместо этого стали вводить добавочный день в феврале каждый третий год (предполагается, что они отсчитывали четвёртый от года, предшествующего високосному). В течение 36 лет после Цезаря високосным был каждый третий год, и лишь затем император Август восстановил правильный порядок следования високосных лет (а также отменил несколько последующих високосных лет, чтобы убрать накопившийся сдвиг). Из сопоставления римских и египетских датировок по оксиринхскому папирусу, опубликованному в 1999 году[5][6], было установлено, что високосными годами в Риме были 42, 39, 36, 33, 30, 27, 24, 21, 18, 15, 12, 9 годы до н. э., 8, 12 годы и в последующем каждый четвёртый год[7].

Григорианский календарь

Продолжительность тропического года (время между двумя весенними равноденствиями) составляет 365 суток 5 часов 48 минут 46 секунд. Различие в продолжительности тропического года и среднего юлианского календарного года (365,25 суток) составляет 11 минут 14 секунд. Из этих 11 минут и 14 секунд приблизительно за 128 лет складываются одни сутки.

По истечении нескольких столетий было замечено смещение дня весеннего равноденствия, с которым связаны церковные праздники. К XVI веку весеннее равноденствие наступало примерно на 10 суток раньше 21 марта, используемого для определения дня Пасхи.

Чтобы компенсировать накопившуюся ошибку и избежать подобного смещения в будущем, в 1582 году римский папа Григорий XIII провёл реформу календаря. Чтобы средний календарный год лучше соответствовал солнечному, было решено изменить правило високосных лет. По-прежнему високосным оставался год, номер которого кратен четырём, но исключение делалось для тех, которые были кратны 100. Такие годы были високосными только тогда, когда делились ещё и на 400.

Другими словами, год является високосным в двух случаях: либо он кратен 4, но при этом не кратен 100, либо кратен 400.

Год не является високосным, если он не кратен 4, либо он кратен 100, но при этом не кратен 400.

Последние годы столетий, оканчивающиеся на два нуля, в трёх случаях из четырёх не являются високосными. Так, годы 1700, 1800 и 1900 не являются високосными, так как они кратны 100 и не кратны 400. Годы 1600 и 2000 — високосные, так как они кратны 400. Годы 2100, 2200 и 2300 — невисокосные. В високосные годы вводится дополнительный день — 29 февраля.

2016 год является високосным годом. Предыдущим високосным годом был 2012 год, следующим будет 2020.

Еврейский календарь

В еврейском календаре високосным годом называют год, к которому добавляют месяц, а не день. Причина этого в том, что еврейский календарь основывается на лунном месяце, и поэтому год из двенадцати месяцев отстаёт от астрономического солнечного года примерно на 11 дней. Для приравнивания лунных лет к солнечному году введён високосный год из тринадцати месяцев. В 19-летний цикл входят 12 простых и 7 високосных лет.

См. также

- 29 февраля

- 30 февраля

- Юлианский календарь

- Новоюлианский календарь

- Високосная секунда

Примечания

- ↑ Толковый словарь русского языка: В 4 т. / Под ред. Д. Н. Ушакова. — М.: Сов. энцикл.: ОГИЗ, 1935—1940.

- ↑ Рус. пер.: Фасмер М. Этимологический словарь русского языка. — 1-е изд. — Т. 1-4. — М., 1964—1973.

- ↑ Полный текст Третьего издания «Большой советской энциклопедии», выпущенной издательством «Советская энциклопедия» в 1969—1978 годах в 30 томах.

- ↑ История и таинства високосного года

- ↑ A. Jones. The Astronomical Papyri from Oxyrhynchus. American Philosophical Society, 1999. ISBN 978-0-87169-233-7. P. 177.

- ↑ Roman to Julian Conversion: Analysis A.U.C. 730 = 24 B.C

- ↑ Климишин И. А. Календарь и хронология. — Изд. 3. — М.: Наука, 1990. — С. 289. — 478 с. — 105 000 экз. — ISBN 5-02-014354-5. (см. ISBN )

Литература

- Високосный год // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907. (см. ISBN )

Шаблон:Единицы измерения и стандарты времени

| Выделить Високосный год и найти в:

|

|

|

- Страница 0 — краткая статья

- Страница 1 — энциклопедическая статья

- Разное — на страницах: 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

- Прошу вносить вашу информацию в «Високосный год 1», чтобы сохранить ее