| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bismuth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (BIZ-məth) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | lustrous brownish silver | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Bi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bismuth in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 83 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 15 (pnictogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

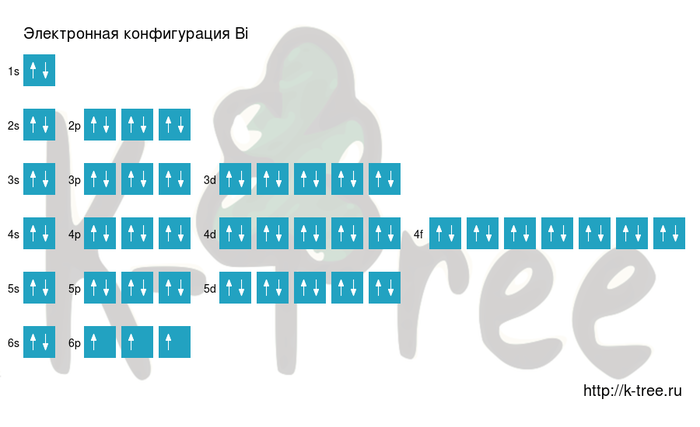

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 544.7 K (271.5 °C, 520.7 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1837 K (1564 °C, 2847 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 9.78 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 10.05 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 11.30 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 179 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.52 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +4, +5 (a mildly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 156 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 148±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 207 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of bismuth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral[3]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 1790 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.4 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 7.97 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1.29 µΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −280.1×10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 32 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 12 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 31 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 70–95 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-69-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Arabic alchemists (before AD 1000) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of bismuth

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Bismuth is a chemical element with the symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs naturally, and its sulfide and oxide forms are important commercial ores. The free element is 86% as dense as lead. It is a brittle metal with a silvery-white color when freshly produced. Surface oxidation generally gives samples of the metal a somewhat rosy cast. Further oxidation under heat can give bismuth a vividly iridescent appearance due to thin-film interference. Bismuth is both the most diamagnetic element and one of the least thermally conductive metals known.

Bismuth was long considered the element with the highest atomic mass whose nuclei do not spontaneously decay. However, in 2003 it was discovered to be extremely weakly radioactive. The metal’s only primordial isotope, bismuth-209, experiences alpha decay at such a minute rate that its half-life is more than a billion times the estimated age of the universe.[5][6] For all but the most exotic of uses bismuth may be considered stable because of its tremendously long half-life.[6]

Bismuth metal has been known since ancient times. Before modern analytical methods bismuth’s metallurgical similarities to lead and tin often led it to be confused with those metals. The etymology of «bismuth» is uncertain. The name may come from mid-sixteenth century New Latin translations of the German words weiße Masse or Wismuth, meaning ‘white mass’, which were rendered as bisemutum or bisemutium.

Main uses[edit]

Bismuth compounds account for about half the global production of bismuth. They are used in cosmetics; pigments; and a few pharmaceuticals, notably bismuth subsalicylate, used to treat diarrhea.[6] Bismuth’s unusual propensity to expand as it solidifies is responsible for some of its uses, as in the casting of printing type.[6] Bismuth has unusually low toxicity for a heavy metal.[6] As the toxicity of lead and the cost of its environmental remediation became more apparent during the 20th century, suitable bismuth alloys have gained popularity as replacements for lead. Presently, around a third of global bismuth production is dedicated to needs formerly met by lead.

History and etymology[edit]

Bismuth metal has been known since ancient times and it was one of the first 10 metals to have been discovered. The name bismuth dates to around 1665 and is of uncertain etymology. The name possibly comes from obsolete German Bismuth, Wismut, Wissmuth (early 16th century), perhaps related to Old High German hwiz («white»).[7] The New Latin bisemutium (coined by Georgius Agricola, who Latinized many German mining and technical words) is from the German Wismuth, itself perhaps from weiße Masse, meaning «white mass».[8][9]

The element was confused in early times with tin and lead because of its resemblance to those elements. Because bismuth has been known since ancient times, no one person is credited with its discovery. Agricola (1546) states that bismuth is a distinct metal in a family of metals including tin and lead. This was based on observation of the metals and their physical properties.[10]

Miners in the age of alchemy also gave bismuth the name tectum argenti, or «silver being made» in the sense of silver still in the process of being formed within the Earth.[11][12][13]

Bismuth was also known to the Incas and used (along with the usual copper and tin) in a special bronze alloy for knives.[14]

Beginning with Johann Heinrich Pott in 1738,[15] Carl Wilhelm Scheele, and Torbern Olof Bergman, the distinctness of lead and bismuth became clear, and Claude François Geoffroy demonstrated in 1753 that this metal is distinct from lead and tin.[12][16][17]

Characteristics[edit]

Left: A bismuth hopper crystal exhibiting the stairstep crystal structure and iridescence colors, which are produced by interference of light within the oxide film on its surface. Right: a 1 cm3 cube of unoxidised bismuth metal

Physical characteristics[edit]

Pressure-temperature phase diagram of bismuth. TC refers to the superconducting transition temperature

Bismuth is a brittle metal with a dark, silver-pink hue, often with an iridescent oxide tarnish showing many colors from yellow to blue. The spiral, stair-stepped structure of bismuth crystals is the result of a higher growth rate around the outside edges than on the inside edges. The variations in the thickness of the oxide layer that forms on the surface of the crystal cause different wavelengths of light to interfere upon reflection, thus displaying a rainbow of colors. When burned in oxygen, bismuth burns with a blue flame and its oxide forms yellow fumes.[16] Its toxicity is much lower than that of its neighbors in the periodic table, such as lead and antimony.

No other metal is verified to be more naturally diamagnetic than bismuth.[16][18] (Superdiamagnetism is a different physical phenomenon.) Of any metal, it has one of the lowest values of thermal conductivity (after manganese, and maybe neptunium and plutonium) and the highest Hall coefficient.[19] It has a high electrical resistivity.[16] When deposited in sufficiently thin layers on a substrate, bismuth is a semiconductor, despite being a post-transition metal.[20] Elemental bismuth is denser in the liquid phase than the solid, a characteristic it shares with germanium, silicon, gallium, and water.[21] Bismuth expands 3.32% on solidification; therefore, it was long a component of low-melting typesetting alloys, where it compensated for the contraction of the other alloying components[16][22][23][24] to form almost isostatic bismuth-lead eutectic alloys.

Though virtually unseen in nature, high-purity bismuth can form distinctive, colorful hopper crystals. It is relatively nontoxic and has a low melting point just above 271 °C, so crystals may be grown using a household stove, although the resulting crystals will tend to be of lower quality than lab-grown crystals.[25]

At ambient conditions, bismuth shares the same layered structure as the metallic forms of arsenic and antimony,[26] crystallizing in the rhombohedral lattice[27] (Pearson symbol hR6, space group R3m No. 166) of the trigonal crystal system.[3] When compressed at room temperature, this Bi-I structure changes first to the monoclinic Bi-II at 2.55 GPa, then to the tetragonal Bi-III at 2.7 GPa, and finally to the body-centered cubic Bi-V at 7.7 GPa. The corresponding transitions can be monitored via changes in electrical conductivity; they are rather reproducible and abrupt and are therefore used for calibration of high-pressure equipment.[28][29]

Chemical characteristics[edit]

Bismuth is stable to both dry and moist air at ordinary temperatures. When red-hot, it reacts with water to make bismuth(III) oxide.[30]

- 2 Bi + 3 H2O → Bi2O3 + 3 H2

It reacts with fluorine to make bismuth(V) fluoride at 500 °C or bismuth(III) fluoride at lower temperatures (typically from Bi melts); with other halogens it yields only bismuth(III) halides.[31][32][33] The trihalides are corrosive and easily react with moisture, forming oxyhalides with the formula BiOX.[34]

- 4 Bi + 6 X2 → 4 BiX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, I)

- 4 BiX3 + 2 O2 → 4 BiOX + 4 X2

Bismuth dissolves in concentrated sulfuric acid to make bismuth(III) sulfate and sulfur dioxide.[30]

- 6 H2SO4 + 2 Bi → 6 H2O + Bi2(SO4)3 + 3 SO2

It reacts with nitric acid to make bismuth(III) nitrate (which decomposes into nitrogen dioxide when heated[35]).[36]

- Bi + 6 HNO3 → 3 H2O + 3 NO2 + Bi(NO3)3

It also dissolves in hydrochloric acid, but only with oxygen present.[30]

- 4 Bi + 3 O2 + 12 HCl → 4 BiCl3 + 6 H2O

It is used as a transmetalating agent in the synthesis of alkaline-earth metal complexes:

- 3 Ba + 2 BiPh3 → 3 BaPh2 + 2 Bi

Isotopes[edit]

The only primordial isotope of bismuth, bismuth-209, was traditionally regarded as the heaviest stable isotope, but it had long been suspected[37] to be unstable on theoretical grounds. This was finally demonstrated in 2003, when researchers at the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France, measured the alpha emission half-life of 209

Bi

to be 2.01×1019 years (3 Bq/Mg),[38][39] over a billion times longer than the current estimated age of the universe.[6] Owing to its extraordinarily long half-life, for all presently known medical and industrial applications, bismuth can be treated as if it is stable and nonradioactive. The radioactivity is of academic interest because bismuth is one of a few elements whose radioactivity was suspected and theoretically predicted before being detected in the laboratory.[6] Bismuth has the longest known alpha decay half-life, although tellurium-128 has a double beta decay half-life of over 2.2×1024 years.[39] Bismuth’s extremely long half-life means that less than approximately one-billionth of the bismuth present at the formation of the planet Earth would have decayed into thallium since then.

Several isotopes of bismuth with short half-lives occur within the radioactive disintegration chains of actinium, radium, and thorium, and more have been synthesized experimentally. Bismuth-213 is also found on the decay chain of neptunium-237 and uranium-233.[40][41]

Commercially, the radioactive isotope bismuth-213 can be produced by bombarding radium with bremsstrahlung photons from a linear particle accelerator. In 1997, an antibody conjugate with bismuth-213, which has a 45-minute half-life and decays with the emission of an alpha particle, was used to treat patients with leukemia. This isotope has also been tried in cancer treatment, for example, in the targeted alpha therapy (TAT) program.[42][43]

Chemical compounds[edit]

Bismuth(III) oxide powder

Bismuth forms trivalent and pentavalent compounds, the trivalent ones being more common. Many of its chemical properties are similar to those of arsenic and antimony, although they are less toxic than derivatives of those lighter elements.[citation needed]

Oxides and sulfides[edit]

At elevated temperatures, the vapors of the metal combine rapidly with oxygen, forming the yellow trioxide, Bi

2O

3.[21][44] When molten, at temperatures above 710 °C, this oxide corrodes any metal oxide and even platinum.[33] On reaction with a base, it forms two series of oxyanions: BiO−

2, which is polymeric and forms linear chains, and BiO3−

3. The anion in Li

3BiO

3 is a cubic octameric anion, Bi

8O24−

24, whereas the anion in Na

3BiO

3 is tetrameric.[45]

The dark red bismuth(V) oxide, Bi

2O

5, is unstable, liberating O

2 gas upon heating.[46] The compound NaBiO3 is a strong oxidising agent.[47]

Bismuth sulfide, Bi

2S

3, occurs naturally in bismuth ores.[48] It is also produced by the combination of molten bismuth and sulfur.[32]

Bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl) structure (mineral bismoclite). Bismuth atoms are shown as grey, oxygen red, chlorine green.

Bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl, see figure at right) and bismuth oxynitrate (BiONO3) stoichiometrically appear as simple anionic salts of the bismuthyl(III) cation (BiO+) which commonly occurs in aqueous bismuth compounds. However, in the case of BiOCl, the salt crystal forms in a structure of alternating plates of Bi, O, and Cl atoms, with each oxygen coordinating with four bismuth atoms in the adjacent plane. This mineral compound is used as a pigment and cosmetic (see below).[49]

Bismuthine and bismuthides[edit]

Unlike the lighter pnictogens nitrogen, phosphorus, and arsenic, but similar to antimony, bismuth does not form a stable hydride. Bismuth hydride, bismuthine (BiH

3), is an endothermic compound that spontaneously decomposes at room temperature. It is stable only below −60 °C.[45] Bismuthides are intermetallic compounds between bismuth and other metals.[50][better source needed]

In 2014 researchers discovered that sodium bismuthide can exist as a form of matter called a “three-dimensional topological Dirac semi-metal” (3DTDS) that possess 3D Dirac fermions in bulk. It is a natural, three-dimensional counterpart to graphene with similar electron mobility and velocity. Graphene and topological insulators (such as those in 3DTDS) are both crystalline materials that are electrically insulating inside but conducting on the surface, allowing them to function as transistors and other electronic devices. While sodium bismuthide (Na

3Bi) is too unstable to be used in devices without packaging, it can demonstrate potential applications of 3DTDS systems, which offer distinct efficiency and fabrication advantages over planar graphene in semiconductor and spintronics applications.[51][52]

Halides[edit]

The halides of bismuth in low oxidation states have been shown to adopt unusual structures. What was originally thought to be bismuth(I) chloride, BiCl, turns out to be a complex compound consisting of Bi5+

9 cations and BiCl2−

5 and Bi

2Cl2−

8 anions.[45][53] The Bi5+

9 cation has a distorted tricapped trigonal prismatic molecular geometry and is also found in Bi

10Hf

3Cl

18, which is prepared by reducing a mixture of hafnium(IV) chloride and bismuth chloride with elemental bismuth, having the structure [Bi+

] [Bi5+

9] [HfCl2−

6]

3.[45]: 50 Other polyatomic bismuth cations are also known, such as Bi2+

8, found in Bi

8(AlCl

4)

2.[53] Bismuth also forms a low-valence bromide with the same structure as «BiCl». There is a true monoiodide, BiI, which contains chains of Bi

4I

4 units. BiI decomposes upon heating to the triiodide, BiI

3, and elemental bismuth. A monobromide of the same structure also exists.[45]

In oxidation state +3, bismuth forms trihalides with all of the halogens: BiF

3, BiCl

3, BiBr

3, and BiI

3. All of these except BiF

3 are hydrolyzed by water.[45]

Bismuth(III) chloride reacts with hydrogen chloride in ether solution to produce the acid HBiCl

4.[30]

The oxidation state +5 is less frequently encountered. One such compound is BiF

5, a powerful oxidizing and fluorinating agent. It is also a strong fluoride acceptor, reacting with xenon tetrafluoride to form the XeF+

3 cation:[30]

- BiF

5 + XeF

4 → XeF+

3BiF−

6

Aqueous species[edit]

In aqueous solution, the Bi3+

ion is solvated to form the aqua ion Bi(H

2O)3+

8 in strongly acidic conditions. At pH > 0 polynuclear species exist, the most important of which is believed to be the octahedral complex [Bi

6O

4(OH)

4]6+

.

Occurrence and production[edit]

Chunk of a broken bismuth ingot

In the Earth’s crust, bismuth is about twice as abundant as gold. The most important ores of bismuth are bismuthinite and bismite.[16] Native bismuth is known from Australia, Bolivia, and China.[56][57]

| Country | Mining sources[58] | Refining sources[59] |

|---|---|---|

| China | 7,400 | 11,000 |

| Vietnam | 2,000 | 5,000 |

| Mexico | 700 | 539 |

| Japan | 428 | |

| Other | 100 | 33 |

| Total | 10,200 | 17,100 |

The difference between mining and refining production reflects bismuth’s status as a byproduct of extraction of other metals such as lead, copper, tin, molybdenum and tungsten.[60] World bismuth production from refineries is a more complete and reliable statistic.[61][62][63]

Bismuth travels in crude lead bullion (which can contain up to 10% bismuth) through several stages of refining, until it is removed by the Kroll-Betterton process which separates the impurities as slag, or the electrolytic Betts process. Bismuth will behave similarly with another of its major metals, copper.[61] The raw bismuth metal from both processes contains still considerable amounts of other metals, foremost lead. By reacting the molten mixture with chlorine gas the metals are converted to their chlorides while bismuth remains unchanged. Impurities can also be removed by various other methods for example with fluxes and treatments yielding high-purity bismuth metal (over 99% Bi).

Price[edit]

World mine production and annual averages of bismuth price (New York, not adjusted for inflation).[64]

The price for pure bismuth metal has been relatively stable through most of the 20th century, except for a spike in the 1970s. Bismuth has always been produced mainly as a byproduct of lead refining, and thus the price usually reflected the cost of recovery and the balance between production and demand.[64]

Prior to World War II, demand for bismuth was small and mainly pharmaceutical — bismuth compounds were used to treat such conditions as digestive disorders, sexually transmitted diseases and burns. Minor amounts of bismuth metal were consumed in fusible alloys for fire sprinkler systems and fuse wire. During World War II bismuth was considered a strategic material, used for solders, fusible alloys, medications and atomic research. To stabilize the market, the producers set the price at $1.25 per pound ($2.75 /kg) during the war and at $2.25 per pound ($4.96 /kg) from 1950 until 1964.[64]

In the early 1970s, the price rose rapidly as a result of increasing demand for bismuth as a metallurgical additive to aluminium, iron and steel. This was followed by a decline owing to increased world production, stabilized consumption, and the recessions of 1980 and 1981–1982. In 1984, the price began to climb as consumption increased worldwide, especially in the United States and Japan. In the early 1990s, research began on the evaluation of bismuth as a nontoxic replacement for lead in ceramic glazes, fishing sinkers, food-processing equipment, free-machining brasses for plumbing applications, lubricating greases, and shot for waterfowl hunting.[65] Growth in these areas remained slow during the middle 1990s, in spite of the backing of lead replacement by the United States federal government, but intensified around 2005. This resulted in a rapid and continuing increase in price.[64]

Recycling[edit]

Most bismuth is produced as a byproduct of other metal-extraction processes including the smelting of lead, and also of tungsten and copper. Its sustainability is dependent on increased recycling, which is problematic.[66]

It was once believed that bismuth could be practically recycled from the soldered joints in electronic equipment. Recent efficiencies in solder application in electronics mean there is substantially less solder deposited, and thus less to recycle. While recovering the silver from silver-bearing solder may remain economic, recovering bismuth is substantially less so.[67]

Next in recycling feasibility would be sizeable catalysts with a fair bismuth content, such as bismuth phosphomolybdate.[citation needed] Bismuth used in galvanizing, and as a free-machining metallurgical additive.[citation needed]

Bismuth in uses where it is dispersed most widely include certain stomach medicines (bismuth subsalicylate), paints (bismuth vanadate), pearlescent cosmetics (bismuth oxychloride), and bismuth-containing bullets. Recycling bismuth from these uses is impractical.[citation needed]

Applications[edit]

18th-century engraving of bismuth processing. During this era, bismuth was used to treat some digestive complaints.

Bismuth has few commercial applications, and those applications that use it generally require small quantities relative to other raw materials. In the United States, for example, 733 tonnes of bismuth were consumed in 2016, of which 70% went into chemicals (including pharmaceuticals, pigments, and cosmetics) and 11% into bismuth alloys.[68]

Some manufacturers use bismuth as a substitute in equipment for potable water systems such as valves to meet «lead-free» mandates in the U.S. (began in 2014). This is a fairly large application since it covers all residential and commercial building construction.[citation needed]

In the early 1990s, researchers began to evaluate bismuth as a nontoxic replacement for lead in various applications.[citation needed]

Medicines[edit]

Bismuth is an ingredient in some pharmaceuticals,[6] although the use of some of these substances is declining.[49]

- Bismuth subsalicylate is used as an antidiarrheal;[6] it is the active ingredient in such «pink bismuth» preparations as Pepto-Bismol, as well as the 2004 reformulation of Kaopectate. It is also used to treat some other gastro-intestinal diseases like shigellosis[69] and cadmium poisoning.[6] The mechanism of action of this substance is still not well documented, although an oligodynamic effect (toxic effect of small doses of heavy metal ions on microbes) may be involved in at least some cases. Salicylic acid from hydrolysis of the compound is antimicrobial for toxogenic E. coli, an important pathogen in traveler’s diarrhea.[70]

- A combination of bismuth subsalicylate and bismuth subcitrate is used to treat the bacteria causing peptic ulcers.[71][72]

- Bibrocathol is an organic bismuth-containing compound used to treat eye infections.[73]

- Bismuth subgallate, the active ingredient in Devrom, is used as an internal deodorant to treat malodor from flatulence and feces.[74][75]

- Bismuth compounds (including sodium bismuth tartrate) were formerly used to treat syphilis.[76][77] Arsenic combined with either bismuth or mercury was a mainstay of syphilis treatment from the 1920s until the advent of penicillin in 1943.[78]

- «Milk of bismuth» (an aqueous suspension of bismuth hydroxide and bismuth subcarbonate) was marketed as an alimentary cure-all in the early 20th century, and has been used to treat gastrointestinal disorders.[79]

- Bismuth subnitrate (Bi5O(OH)9(NO3)4) and bismuth subcarbonate (Bi2O2(CO3)) are also used in medicine.[16]

Cosmetics and pigments[edit]

Bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl) is sometimes used in cosmetics, as a pigment in paint for eye shadows, hair sprays and nail polishes.[6][49][80][81] This compound is found as the mineral bismoclite and in crystal form contains layers of atoms (see figure above) that refract light chromatically, resulting in an iridescent appearance similar to nacre of pearl. It was used as a cosmetic in ancient Egypt and in many places since. Bismuth white (also «Spanish white») can refer to either bismuth oxychloride or bismuth oxynitrate (BiONO3), when used as a white pigment.[82] Bismuth vanadate is used as a light-stable non-reactive paint pigment (particularly for artists’ paints), often as a replacement for the more toxic cadmium sulfide yellow and orange-yellow pigments. The most common variety in artists’ paints is a lemon yellow, visually indistinguishable from its cadmium-containing alternative.[citation needed]

Metal and alloys[edit]

Bismuth is used in metal alloys with other metals such as iron. These alloys are used in automatic sprinkler systems for fires. It forms the largest part (50%) of Rose’s metal, a fusible alloy, which also contains 25–28% lead and 22–25% tin. It was also used to make bismuth bronze which was used in the Bronze Age, having been found in Inca knives at Machu Picchu.[83]

Lead replacement[edit]

The density difference between lead (11.32 g/cm3) and bismuth (9.78 g/cm3) is small enough that for many ballistics and weighting applications, bismuth can substitute for lead. For example, it can replace lead as a dense material in fishing sinkers. It has been used as a replacement for lead in shot, bullets and less-lethal riot gun ammunition. The Netherlands, Denmark, England, Wales, the United States, and many other countries now prohibit the use of lead shot for the hunting of wetland birds, as many birds are prone to lead poisoning owing to mistaken ingestion of lead (instead of small stones and grit) to aid digestion, or even prohibit the use of lead for all hunting, such as in the Netherlands. Bismuth-tin alloy shot is one alternative that provides similar ballistic performance to lead. (Another less expensive but also more poorly performing alternative is «steel» shot, which is actually soft iron.) Bismuth’s lack of malleability does, however, make it unsuitable for use in expanding hunting bullets.[citation needed]

Bismuth, as a dense element of high atomic weight, is used in bismuth-impregnated latex shields to shield from X-ray in medical examinations, such as CTs, mostly as it is considered non-toxic.[84]

The European Union’s Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive (RoHS) for reduction of lead has broadened bismuth’s use in electronics as a component of low-melting point solders, as a replacement for traditional tin-lead solders.[68] Its low toxicity will be especially important for solders to be used in food processing equipment and copper water pipes, although it can also be used in other applications including those in the automobile industry, in the European Union, for example.[85]

Bismuth has been evaluated as a replacement for lead in free-machining brasses for plumbing applications,[86] although it does not equal the performance of leaded steels.[85]

Other metal uses and specialty alloys[edit]

Many bismuth alloys have low melting points and are found in specialty applications such as solders. Many automatic sprinklers, electric fuses, and safety devices in fire detection and suppression systems contain the eutectic In19.1-Cd5.3-Pb22.6-Sn8.3-Bi44.7 alloy that melts at 47 °C (117 °F)[16] This is a convenient temperature since it is unlikely to be exceeded in normal living conditions. Low-melting alloys, such as Bi-Cd-Pb-Sn alloy which melts at 70 °C, are also used in automotive and aviation industries. Before deforming a thin-walled metal part, it is filled with a melt or covered with a thin layer of the alloy to reduce the chance of breaking. Then the alloy is removed by submerging the part in boiling water.[87]

Bismuth is used to make free-machining steels and free-machining aluminium alloys for precision machining properties. It has similar effect to lead and improves the chip breaking during machining. The shrinking on solidification in lead and the expansion of bismuth compensate each other and therefore lead and bismuth are often used in similar quantities.[88][89] Similarly, alloys containing comparable parts of bismuth and lead exhibit a very small change (on the order 0.01%) upon melting, solidification or aging. Such alloys are used in high-precision casting, e.g. in dentistry, to create models and molds.[87] Bismuth is also used as an alloying agent in production of malleable irons[68] and as a thermocouple material.[16]

Bismuth is also used in aluminium-silicon cast alloys in order to refine silicon morphology. However, it indicated a poisoning effect on modification of strontium.[90][91] Some bismuth alloys, such as Bi35-Pb37-Sn25, are combined with non-sticking materials such as mica, glass and enamels because they easily wet them allowing to make joints to other parts. Addition of bismuth to caesium enhances the quantum yield of caesium cathodes.[49] Sintering of bismuth and manganese powders at 300 °C produces a permanent magnet and magnetostrictive material, which is used in ultrasonic generators and receivers working in the 10–100 kHz range and in magnetic and holographic memory devices.[92]

Other uses as compounds[edit]

Bismuth vanadate, a yellow pigment

- Bismuth is included in BSCCO (bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide) which is a group of similar superconducting compounds discovered in 1988 that exhibit the highest superconducting transition temperatures.[93]

- Bismuth subnitrate is a component of glazes that produces an iridescence and is used as a pigment in paint.

- Bismuth telluride is a semiconductor and an excellent thermoelectric material.[49][94] Bi2Te3 diodes are used in mobile refrigerators, CPU coolers, and as detectors in infrared spectrophotometers.[49]

- Bismuth oxide, in its delta form, is a solid electrolyte for oxygen. This form normally breaks down below a high-temperature threshold, but can be electrodeposited well below this temperature in a highly alkaline solution.

- Bismuth germanate is a scintillator, widely used in X-ray and gamma ray detectors.

- Bismuth vanadate is an opaque yellow pigment used by some artists’ oil, acrylic, and watercolor paint companies, primarily as a replacement for the more toxic cadmium sulfide yellows in the greenish-yellow (lemon) to orange-toned yellow range. It performs practically identically to the cadmium pigments, such as in terms of resistance to degradation from UV exposure, opacity, tinting strength, and lack of reactivity when mixed with other pigments. The most commonly-used variety by artists’ paint makers is lemon in color. In addition to being a replacement for several cadmium yellows, it also serves as a non-toxic visual replacement for the older chromate pigments made with zinc, lead, and strontium. If a green pigment and barium sulfate (for increased transparency) are added it can also serve as a replacement for barium chromate, which possesses a more greenish cast than the others. In comparison with lead chromate, it does not blacken due to hydrogen sulfide in the air (a process accelerated by UV exposure) and possesses a particularly brighter color than them, especially the lemon, which is the most translucent, dull, and fastest to blacken due to the higher percentage of lead sulfate required to produce that shade. It is also used, on a limited basis due to its cost, as a vehicle paint pigment.[95][96]

- A catalyst for making acrylic fibers.[16]

- As an electrocatalyst in the conversion of CO2 to CO.[97]

- Ingredient in lubricating greases.[98]

- In crackling microstars (dragon’s eggs) in pyrotechnics, as the oxide, subcarbonate or subnitrate.[99][100]

- As catalyst for the fluorination of arylboronic pinacol esters through a Bi(III)/Bi(V) catalytic cycle, mimicking transition metals in electrophilic fluorination.[101]

Toxicology and ecotoxicology[edit]

- See also bismuthia, a rare dermatological condition that results from the prolonged use of bismuth.

Scientific literature indicates that some of the compounds of bismuth are less toxic to humans via ingestion than other heavy metals (lead, arsenic, antimony, etc.)[6] presumably due to the comparatively low solubility of bismuth salts.[102] Its biological half-life for whole-body retention is reported to be 5 days but it can remain in the kidney for years in people treated with bismuth compounds.[103]

Bismuth poisoning can occur and has according to some reports been common in relatively recent times.[102][104] As with lead, bismuth poisoning can result in the formation of a black deposit on the gingiva, known as a bismuth line.[105][106][107] Poisoning may be treated with dimercaprol; however, evidence for benefit is unclear.[108][109]

Bismuth’s environmental impacts are not well known; it may be less likely to bioaccumulate than some other heavy metals, and this is an area of active research.[110][111]

See also[edit]

- Lead-bismuth eutectic

- List of countries by bismuth production

- Bismuth minerals

- Patterns in nature

References[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Bismuth». CIAAW. 2005.

- ^ Bi(0) state is known to exist in a N-heterocyclic carbene complex of dibismuthene; see Deka, Rajesh; Orthaber, Andreas (6 May 2022). «Carbene chemistry of arsenic, antimony, and bismuth: origin, evolution and future prospects». Royal Society of Chemistry (51): 8540. doi:10.1039/d2dt00755j.

- ^ a b Cucka, P.; Barrett, C. S. (1962). «The crystal structure of Bi and of solid solutions of Pb, Sn, Sb and Te in Bi». Acta Crystallographica. 15 (9): 865. doi:10.1107/S0365110X62002297.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Dumé, Belle (23 April 2003). «Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay». Physicsworld.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kean, Sam (2011). The Disappearing Spoon (and other true tales of madness, love, and the history of the world from the Periodic Table of Elements). New York/Boston: Back Bay Books. pp. 158–160. ISBN 978-0-316-051637.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «bismuth». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bismuth, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology

- ^ Norman, Nicholas C. (1998). Chemistry of Arsenic, Antimony, and Bismuth. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7514-0389-3.

- ^ Agricola, Georgious (1955) [1546]. De Natura Fossilium. New York: Mineralogical Society of America. p. 178.

- ^ Nicholson, William (1819). «Bismuth». American edition of the British encyclopedia: Or, Dictionary of Arts and sciences; comprising an accurate and popular view of the present improved state of human knowledge. p. 181.

- ^ a b Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements. II. Elements known to the alchemists». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 11. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9…11W. doi:10.1021/ed009p11.

- ^ Giunta, Carmen J. «Glossary of Archaic Chemical Terms». Le Moyne College. See also for other terms for bismuth, including stannum glaciale (glacial tin or ice-tin).

- ^ Gordon, Robert B.; Rutledge, John W. (1984). «Bismuth Bronze from Machu Picchu, Peru». Science. 223 (4636): 585–586. Bibcode:1984Sci…223..585G. doi:10.1126/science.223.4636.585. JSTOR 1692247. PMID 17749940. S2CID 206572055.

- ^ Pott, Johann Heinrich (1738). «De Wismutho». Exercitationes Chymicae. Berolini: Apud Johannem Andream Rüdigerum. p. 134.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hammond, C. R. (2004). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). Boca Raton (FL, US): CRC press. pp. 4–1. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- ^ Geoffroy, C.F. (1753). «Sur Bismuth». Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences … Avec les Mémoires de Mathématique & de Physique … Tirez des Registres de Cette Académie: 190.

- ^ Krüger, p. 171.

- ^ Jones, H. (1936). «The Theory of the Galvomagnetic Effects in Bismuth». Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 155 (886): 653–663. Bibcode:1936RSPSA.155..653J. doi:10.1098/rspa.1936.0126. JSTOR 96773.

- ^ Hoffman, C.; Meyer, J.; Bartoli, F.; Di Venere, A.; Yi, X.; Hou, C.; Wang, H.; Ketterson, J.; Wong, G. (1993). «Semimetal-to-semiconductor transition in bismuth thin films». Phys. Rev. B. 48 (15): 11431–11434. Bibcode:1993PhRvB..4811431H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.48.11431. PMID 10007465.

- ^ a b Wiberg, p. 768.

- ^ Tracy, George R.; Tropp, Harry E.; Friedl, Alfred E. (1974). Modern physical science. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-03-007381-6.

- ^ Tribe, Alfred (1868). «IX.—Freezing of water and bismuth». Journal of the Chemical Society. 21: 71. doi:10.1039/JS8682100071.

- ^ Papon, Pierre; Leblond, Jacques; Meijer, Paul Herman Ernst (2006). The Physics of Phase Transitions. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-540-33390-6.

- ^ Tiller, William A. (1991). The science of crystallization: microscopic interfacial phenomena. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-38827-6.

- ^ Wiberg, p. 767.

- ^ Krüger, p. 172.

- ^ Boldyreva, Elena (2010). High-Pressure Crystallography: From Fundamental Phenomena to Technological Applications. Springer. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-90-481-9257-1.

- ^ Manghnani, Murli H. (25–30 July 1999). Science and Technology of High Pressure: Proceedings of the International Conference on High Pressure Science and Technology (AIRAPT-17). Vol. 2. Honolulu, Hawaii: Universities Press (India) (published 2000). p. 1086. ISBN 978-81-7371-339-2.

- ^ a b c d e Suzuki, p. 8.

- ^ Wiberg, pp. 769–770.

- ^ a b Greenwood, pp. 559–561.

- ^ a b Krüger, p. 185

- ^ Suzuki, p. 9.

- ^ Krabbe, S.W.; Mohan, R.S. (2012). «Environmentally friendly organic synthesis using Bi(III) compounds». In Ollevier, Thierry (ed.). Topics in Current chemistry 311, Bismuth-Mediated Organic Reactions. Springer. pp. 100–110. ISBN 978-3-642-27239-4.

- ^ Rich, Ronald (2007). Inorganic Reactions in Water (e-book). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-73962-3.

- ^ Carvalho, H. G.; Penna, M. (1972). «Alpha-activity of 209

Bi

«. Lettere al Nuovo Cimento. 3 (18): 720. doi:10.1007/BF02824346. S2CID 120952231. - ^ Marcillac, Pierre de; Noël Coron; Gérard Dambier; Jacques Leblanc & Jean-Pierre Moalic (2003). «Experimental detection of α-particles from the radioactive decay of natural bismuth». Nature. 422 (6934): 876–878. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..876D. doi:10.1038/nature01541. PMID 12712201. S2CID 4415582.

- ^ a b Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). «The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties» (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ^ Loveland, Walter D.; Morrissey, David J.; Seaborg, Glenn T. (2006). Modern Nuclear Chemistry. p. 78. Bibcode:2005mnc..book…..L. ISBN 978-0-471-11532-8.

- ^ Peppard, D. F.; Mason, G. W.; Gray, P. R.; Mech, J. F. (1952). «Occurrence of the (4n + 1) series in nature» (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (23): 6081–6084. doi:10.1021/ja01143a074.

- ^ Imam, S. (2001). «Advancements in cancer therapy with alpha-emitters: a review». International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 51 (1): 271–8. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01585-1. PMID 11516878.

- ^ Acton, Ashton (2011). Issues in Cancer Epidemiology and Research. p. 520. ISBN 978-1-4649-6352-0.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 553.

- ^ a b c d e f Godfrey, S. M.; McAuliffe, C. A.; Mackie, A. G.; Pritchard, R. G. (1998). Nicholas C. Norman (ed.). Chemistry of arsenic, antimony, and bismuth. Springer. pp. 67–84. ISBN 978-0-7514-0389-3.

- ^ Scott, Thomas; Eagleson, Mary (1994). Concise encyclopedia chemistry. Walter de Gruyter. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 578.

- ^ An Introduction to the Study of Chemistry. Forgotten Books. p. 363. ISBN 978-1-4400-5235-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Krüger, p. 184.

- ^ «bismuthide». Your Dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ «3D counterpart to graphene discovered [UPDATE]». KurzweilAI. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Liu, Z. K.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. J.; Weng, H. M.; Prabhakaran, D.; Mo, S. K.; Shen, Z. X.; Fang, Z.; Dai, X.; Hussain, Z.; Chen, Y. L. (2014). «Discovery of a Three-Dimensional Topological Dirac Semimetal, Na3Bi». Science. 343 (6173): 864–7. arXiv:1310.0391. Bibcode:2014Sci…343..864L. doi:10.1126/science.1245085. PMID 24436183. S2CID 206552029.

- ^ a b Gillespie, R. J.; Passmore, J. (1975). Emeléus, H. J.; Sharp A. G. (eds.). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry. Academic Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-12-023617-6.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (eds.). «Bismuth» (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy: Elements, Sulfides, Sulfosalts. Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 978-0-9622097-0-3. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ Krüger, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Anderson, Schuyler C. «2017 USGS Minerals Yearbook: Bismuth» (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Klochko, Kateryna. «2018 USGS Minerals Yearbook: Bismuth» (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Krüger, p. 173.

- ^ a b Ojebuoboh, Funsho K. (1992). «Bismuth—Production, properties, and applications». JOM. 44 (4): 46–49. Bibcode:1992JOM….44d..46O. doi:10.1007/BF03222821. S2CID 52993615.

- ^ Horsley, G. W. (1957). «The preparation of bismuth for use in a liquid-metal fuelled reactor». Journal of Nuclear Energy. 6 (1–2): 41. doi:10.1016/0891-3919(57)90180-8.

- ^ Shevtsov, Yu. V.; Beizel’, N. F. (2011). «Pb distribution in multistep bismuth refining products». Inorganic Materials. 47 (2): 139. doi:10.1134/S0020168511020166. S2CID 96931735.

- ^ a b c d Bismuth Statistics and Information. see «Metal Prices in the United States through 1998» for a price summary and «Historical Statistics for Mineral and Material Commodities in the United States» for production. USGS.

- ^ Suzuki, p. 14.

- ^ European Commission. Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. (2018). Report on critical raw materials and the circular economy. LU: Publications Office. doi:10.2873/167813.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Warburg, N. «IKP, Department of Life-Cycle Engineering» (PDF). University of Stuttgart. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Klochko, Kateryna. «2016 USGS Minerals Yearbook: Bismuth» (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

- ^ CDC, shigellosis.

- ^ Sox TE; Olson CA (1989). «Binding and killing of bacteria by bismuth subsalicylate». Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 33 (12): 2075–82. doi:10.1128/AAC.33.12.2075. PMC 172824. PMID 2694949.

- ^ «P/74/2009: European Medicines Agency decision of 20 April 2009 on the granting of a product specific waiver for Bismuth subcitrate potassium / Metronidazole / Tetracycline hydrochloride (EMEA-000382-PIP01-08) in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council as amended» (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 10 June 2009.

- ^ Urgesi R, Cianci R, Riccioni ME (2012). «Update on triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: current status of the art». Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 5: 151–7. doi:10.2147/CEG.S25416. PMC 3449761. PMID 23028235.

- ^ Gurtler L (January 2002). «Chapter 2: The Eye and Conjunctiva as Target of Entry for Infectious Agents: Prevention by Protection and by Antiseptic Prophylaxis». In Kramer A, Behrens-Baumann W (eds.). Antiseptic prophylaxis and therapy in ocular infections: principles, clinical practice, and infection control. Developments in Ophthalmology. Vol. 33. Basel: Karger. pp. 9–13. doi:10.1159/000065934. ISBN 978-3-8055-7316-0. PMID 12236131.

- ^ Gorbach SL (September 1990). «Bismuth therapy in gastrointestinal diseases». Gastroenterology. 99 (3): 863–75. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(90)90983-8. PMID 2199292.

- ^ Sparberg M (March 1974). «Correspondence: Bismuth subgallate as an effective means for the control of ileostomy odor: a double blind study». Gastroenterology. 66 (3): 476. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(74)80150-2. PMID 4813513.

- ^ Parnell, R. J. G. (1924). «Bismuth in the Treatment of Syphilis». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 17 (War section): 19–26. doi:10.1177/003591572401702604. PMC 2201253. PMID 19984212.

- ^ Giemsa, Gustav (1924) U.S. Patent 1,540,117 «Manufacture of bismuth tartrates»

- ^ Frith, John (November 2012). «Syphilis — Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin, and the Debate on its Origins». Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health. 20 (4): 54. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ «Milk of Bismuth». Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Maile, Frank J.; Pfaff, Gerhard; Reynders, Peter (2005). «Effect pigments—past, present and future». Progress in Organic Coatings. 54 (3): 150. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.07.003.

- ^ Pfaff, Gerhard (2008). Special effect pigments: Technical basics and applications. Vincentz Network GmbH. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-86630-905-0.

- ^ Sadler, Peter J (1991). «Chapter 1». In Sykes, A.G. (ed.). ADVANCES IN INORGANIC CHEMISTRY, Volume 36. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-023636-2.

- ^ Gordon, Robert B.; Rutledge, John W. (1984). «Bismuth Bronze from Machu Picchu, Peru». Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 223 (4636): 585–586. Bibcode:1984Sci…223..585G. doi:10.1126/science.223.4636.585. JSTOR 1692247. PMID 17749940. S2CID 206572055.

- ^ Hopper KD; King SH; Lobell ME; TenHave TR; Weaver JS (1997). «The breast: inplane x-ray protection during diagnostic thoracic CT—shielding with bismuth radioprotective garments». Radiology. 205 (3): 853–8. doi:10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393547. PMID 9393547.

- ^ a b Lohse, Joachim; Zangl, Stéphanie; Groß, Rita; Gensch, Carl-Otto; Deubzer, Otmar (September 2007). «Adaptation to Scientific and Technical Progress of Annex II Directive 2000/53/EC» (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ La Fontaine, A.; Keast, V. J. (2006). «Compositional distributions in classical and lead-free brasses». Materials Characterization. 57 (4–5): 424. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2006.02.005.

- ^ a b Krüger, p. 183.

- ^ Llewellyn, D. T.; Hudd, Roger C. (1998). Steels: Metallurgy and applications. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-7506-3757-2.

- ^ Davis & Associates, J. R. & Handbook Committee, ASM International (1993). Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-87170-496-2.

- ^ Farahany, Saeed; A. Ourdjini; M.H. Idris; L.T. Thai (2011). «Poisoning effect of bismuth on modification behavior of strontium in LM25 alloy». Journal of Bulletin of Materials Science. 34 (6): 1223–1231. doi:10.1007/s12034-011-0239-5.

- ^ Farahany, Saeed; A. Ourdjini; M. H. Idris; L.T. Thai (2011). «Effect of bismuth on the microstructure of unmodified and Sr-modified Al-7%Si-0.4Mg alloy». Journal of Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 21 (7): 1455–1464. doi:10.1016/S1003-6326(11)60881-9. S2CID 73719425.

- ^ Suzuki, p. 15.

- ^ «BSCCO». National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ Tritt, Terry M. (2000). Recent trends in thermoelectric materials research. Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-12-752178-7.

- ^ Tücks, Andreas; Beck, Horst P. (2007). «The photochromic effect of bismuth vanadate pigments: Investigations on the photochromic mechanism». Dyes and Pigments. 72 (2): 163. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2005.08.027.

- ^ Müller, Albrecht (2003). «Yellow pigments». Coloring of plastics: Fundamentals, colorants, preparations. Hanser Verlag. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-1-56990-352-0.

- ^ DiMeglio, John L.; Rosenthal, Joel (2013). «Selective conversion of CO2 to CO with high efficiency using an bismuth-based electrocatalyst». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 135 (24): 8798–8801. doi:10.1021/ja4033549. PMC 3725765. PMID 23735115.

- ^ Mortier, Roy M.; Fox, Malcolm F.; Orszulik, Stefan T. (2010). Chemistry and Technology of Lubricants. Springer. p. 430. Bibcode:2010ctl..book…..M. ISBN 978-1-4020-8661-8.

- ^ Croteau, Gerry; Dills, Russell; Beaudreau, Marc; Davis, Mac (2010). «Emission factors and exposures from ground-level pyrotechnics». Atmospheric Environment. 44 (27): 3295. Bibcode:2010AtmEn..44.3295C. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.05.048.

- ^ Ledgard, Jared (2006). The Preparatory Manual of Black Powder and Pyrotechnics. Lulu. pp. 207, 319, 370, 518, search. ISBN 978-1-4116-8574-1.

- ^ Planas, Oriol; Wang, Feng; Leutzsch, Markus; Cornella, Josep (2020). «Fluorination of arylboronic esters enabled by bismuth redox catalysis». Science. 367 (6475): 313–317. Bibcode:2020Sci…367..313P. doi:10.1126/science.aaz2258. PMID 31949081. S2CID 210698047.

- ^ a b DiPalma, Joseph R. (2001). «Bismuth Toxicity, Often Mild, Can Result in Severe Poisonings». Emergency Medicine News. 23 (3): 16. doi:10.1097/00132981-200104000-00012.

- ^ Fowler, B.A. & Sexton M.J. (2007). «Bismuth». In Nordberg, Gunnar (ed.). Handbook on the toxicology of metals. Academic Press. pp. 433 ff. ISBN 978-0-12-369413-3.

- ^ Data on Bismuth’s health and environmental effects. Lenntech.com. Retrieved on 17 December 2011.

- ^ «Bismuth line» in TheFreeDictionary’s Medical dictionary. Farlex, Inc.

- ^ Levantine, Ashley; Almeyda, John (1973). «Drug induced changes in pigmentation». British Journal of Dermatology. 89 (1): 105–12. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb01932.x. PMID 4132858. S2CID 7175799.

- ^ Krüger, pp. 187–188.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 62. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ «Dimercaprol». The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Boriova; et al. (2015). «Bismuth(III) Volatilization and Immobilization by Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus clavatus During Aerobic Incubation». Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 68 (2): 405–411. doi:10.1007/s00244-014-0096-5. PMID 25367214. S2CID 30197424.

- ^ Boriova; et al. (2013). «Bioaccumulation and biosorption of bismuth Bi (III) by filamentous fungus Aspergillus clavatus» (PDF). Student Scientific Conference PriF UK 2013. Proceedings of Reviewed Contributions.

Bibliography[edit]

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Brown, R. D., Jr. «Annual Average Bismuth Price», USGS (1998)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Brown, R. D., Jr. «Annual Average Bismuth Price», USGS (1998)

- Greenwood, N. N. & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- Krüger, Joachim; Winkler, Peter; Lüderitz, Eberhard; Lück, Manfred; Wolf, Hans Uwe (2003). «Bismuth, Bismuth Alloys, and Bismuth Compounds». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. pp. 171–189. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_171. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Suzuki, Hitomi (2001). Organobismuth Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-444-20528-5.

- Wiberg, Egon; Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Nils (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

External links[edit]

![]()

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bismuth.

![]()

Look up bismuth in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Laboratory growth of large crystals of Bismuth by Jan Kihle Crystal Pulling Laboratories, Norway

- Bismuth at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay

- Bismuth Crystals – Instructions & Pictures

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bismuth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (BIZ-məth) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | lustrous brownish silver | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Bi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bismuth in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 83 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 15 (pnictogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 544.7 K (271.5 °C, 520.7 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1837 K (1564 °C, 2847 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 9.78 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 10.05 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 11.30 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 179 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.52 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +4, +5 (a mildly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 156 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 148±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 207 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of bismuth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral[3]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 1790 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.4 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 7.97 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1.29 µΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −280.1×10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 32 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 12 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 31 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 70–95 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-69-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Arabic alchemists (before AD 1000) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of bismuth

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Bismuth is a chemical element with the symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs naturally, and its sulfide and oxide forms are important commercial ores. The free element is 86% as dense as lead. It is a brittle metal with a silvery-white color when freshly produced. Surface oxidation generally gives samples of the metal a somewhat rosy cast. Further oxidation under heat can give bismuth a vividly iridescent appearance due to thin-film interference. Bismuth is both the most diamagnetic element and one of the least thermally conductive metals known.

Bismuth was long considered the element with the highest atomic mass whose nuclei do not spontaneously decay. However, in 2003 it was discovered to be extremely weakly radioactive. The metal’s only primordial isotope, bismuth-209, experiences alpha decay at such a minute rate that its half-life is more than a billion times the estimated age of the universe.[5][6] For all but the most exotic of uses bismuth may be considered stable because of its tremendously long half-life.[6]

Bismuth metal has been known since ancient times. Before modern analytical methods bismuth’s metallurgical similarities to lead and tin often led it to be confused with those metals. The etymology of «bismuth» is uncertain. The name may come from mid-sixteenth century New Latin translations of the German words weiße Masse or Wismuth, meaning ‘white mass’, which were rendered as bisemutum or bisemutium.

Main uses[edit]

Bismuth compounds account for about half the global production of bismuth. They are used in cosmetics; pigments; and a few pharmaceuticals, notably bismuth subsalicylate, used to treat diarrhea.[6] Bismuth’s unusual propensity to expand as it solidifies is responsible for some of its uses, as in the casting of printing type.[6] Bismuth has unusually low toxicity for a heavy metal.[6] As the toxicity of lead and the cost of its environmental remediation became more apparent during the 20th century, suitable bismuth alloys have gained popularity as replacements for lead. Presently, around a third of global bismuth production is dedicated to needs formerly met by lead.

History and etymology[edit]

Bismuth metal has been known since ancient times and it was one of the first 10 metals to have been discovered. The name bismuth dates to around 1665 and is of uncertain etymology. The name possibly comes from obsolete German Bismuth, Wismut, Wissmuth (early 16th century), perhaps related to Old High German hwiz («white»).[7] The New Latin bisemutium (coined by Georgius Agricola, who Latinized many German mining and technical words) is from the German Wismuth, itself perhaps from weiße Masse, meaning «white mass».[8][9]

The element was confused in early times with tin and lead because of its resemblance to those elements. Because bismuth has been known since ancient times, no one person is credited with its discovery. Agricola (1546) states that bismuth is a distinct metal in a family of metals including tin and lead. This was based on observation of the metals and their physical properties.[10]

Miners in the age of alchemy also gave bismuth the name tectum argenti, or «silver being made» in the sense of silver still in the process of being formed within the Earth.[11][12][13]

Bismuth was also known to the Incas and used (along with the usual copper and tin) in a special bronze alloy for knives.[14]

Beginning with Johann Heinrich Pott in 1738,[15] Carl Wilhelm Scheele, and Torbern Olof Bergman, the distinctness of lead and bismuth became clear, and Claude François Geoffroy demonstrated in 1753 that this metal is distinct from lead and tin.[12][16][17]

Characteristics[edit]

Left: A bismuth hopper crystal exhibiting the stairstep crystal structure and iridescence colors, which are produced by interference of light within the oxide film on its surface. Right: a 1 cm3 cube of unoxidised bismuth metal

Physical characteristics[edit]

Pressure-temperature phase diagram of bismuth. TC refers to the superconducting transition temperature

Bismuth is a brittle metal with a dark, silver-pink hue, often with an iridescent oxide tarnish showing many colors from yellow to blue. The spiral, stair-stepped structure of bismuth crystals is the result of a higher growth rate around the outside edges than on the inside edges. The variations in the thickness of the oxide layer that forms on the surface of the crystal cause different wavelengths of light to interfere upon reflection, thus displaying a rainbow of colors. When burned in oxygen, bismuth burns with a blue flame and its oxide forms yellow fumes.[16] Its toxicity is much lower than that of its neighbors in the periodic table, such as lead and antimony.

No other metal is verified to be more naturally diamagnetic than bismuth.[16][18] (Superdiamagnetism is a different physical phenomenon.) Of any metal, it has one of the lowest values of thermal conductivity (after manganese, and maybe neptunium and plutonium) and the highest Hall coefficient.[19] It has a high electrical resistivity.[16] When deposited in sufficiently thin layers on a substrate, bismuth is a semiconductor, despite being a post-transition metal.[20] Elemental bismuth is denser in the liquid phase than the solid, a characteristic it shares with germanium, silicon, gallium, and water.[21] Bismuth expands 3.32% on solidification; therefore, it was long a component of low-melting typesetting alloys, where it compensated for the contraction of the other alloying components[16][22][23][24] to form almost isostatic bismuth-lead eutectic alloys.

Though virtually unseen in nature, high-purity bismuth can form distinctive, colorful hopper crystals. It is relatively nontoxic and has a low melting point just above 271 °C, so crystals may be grown using a household stove, although the resulting crystals will tend to be of lower quality than lab-grown crystals.[25]

At ambient conditions, bismuth shares the same layered structure as the metallic forms of arsenic and antimony,[26] crystallizing in the rhombohedral lattice[27] (Pearson symbol hR6, space group R3m No. 166) of the trigonal crystal system.[3] When compressed at room temperature, this Bi-I structure changes first to the monoclinic Bi-II at 2.55 GPa, then to the tetragonal Bi-III at 2.7 GPa, and finally to the body-centered cubic Bi-V at 7.7 GPa. The corresponding transitions can be monitored via changes in electrical conductivity; they are rather reproducible and abrupt and are therefore used for calibration of high-pressure equipment.[28][29]

Chemical characteristics[edit]

Bismuth is stable to both dry and moist air at ordinary temperatures. When red-hot, it reacts with water to make bismuth(III) oxide.[30]

- 2 Bi + 3 H2O → Bi2O3 + 3 H2

It reacts with fluorine to make bismuth(V) fluoride at 500 °C or bismuth(III) fluoride at lower temperatures (typically from Bi melts); with other halogens it yields only bismuth(III) halides.[31][32][33] The trihalides are corrosive and easily react with moisture, forming oxyhalides with the formula BiOX.[34]

- 4 Bi + 6 X2 → 4 BiX3 (X = F, Cl, Br, I)

- 4 BiX3 + 2 O2 → 4 BiOX + 4 X2

Bismuth dissolves in concentrated sulfuric acid to make bismuth(III) sulfate and sulfur dioxide.[30]

- 6 H2SO4 + 2 Bi → 6 H2O + Bi2(SO4)3 + 3 SO2

It reacts with nitric acid to make bismuth(III) nitrate (which decomposes into nitrogen dioxide when heated[35]).[36]

- Bi + 6 HNO3 → 3 H2O + 3 NO2 + Bi(NO3)3

It also dissolves in hydrochloric acid, but only with oxygen present.[30]

- 4 Bi + 3 O2 + 12 HCl → 4 BiCl3 + 6 H2O

It is used as a transmetalating agent in the synthesis of alkaline-earth metal complexes:

- 3 Ba + 2 BiPh3 → 3 BaPh2 + 2 Bi

Isotopes[edit]

The only primordial isotope of bismuth, bismuth-209, was traditionally regarded as the heaviest stable isotope, but it had long been suspected[37] to be unstable on theoretical grounds. This was finally demonstrated in 2003, when researchers at the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France, measured the alpha emission half-life of 209

Bi

to be 2.01×1019 years (3 Bq/Mg),[38][39] over a billion times longer than the current estimated age of the universe.[6] Owing to its extraordinarily long half-life, for all presently known medical and industrial applications, bismuth can be treated as if it is stable and nonradioactive. The radioactivity is of academic interest because bismuth is one of a few elements whose radioactivity was suspected and theoretically predicted before being detected in the laboratory.[6] Bismuth has the longest known alpha decay half-life, although tellurium-128 has a double beta decay half-life of over 2.2×1024 years.[39] Bismuth’s extremely long half-life means that less than approximately one-billionth of the bismuth present at the formation of the planet Earth would have decayed into thallium since then.

Several isotopes of bismuth with short half-lives occur within the radioactive disintegration chains of actinium, radium, and thorium, and more have been synthesized experimentally. Bismuth-213 is also found on the decay chain of neptunium-237 and uranium-233.[40][41]

Commercially, the radioactive isotope bismuth-213 can be produced by bombarding radium with bremsstrahlung photons from a linear particle accelerator. In 1997, an antibody conjugate with bismuth-213, which has a 45-minute half-life and decays with the emission of an alpha particle, was used to treat patients with leukemia. This isotope has also been tried in cancer treatment, for example, in the targeted alpha therapy (TAT) program.[42][43]

Chemical compounds[edit]

Bismuth(III) oxide powder

Bismuth forms trivalent and pentavalent compounds, the trivalent ones being more common. Many of its chemical properties are similar to those of arsenic and antimony, although they are less toxic than derivatives of those lighter elements.[citation needed]

Oxides and sulfides[edit]

At elevated temperatures, the vapors of the metal combine rapidly with oxygen, forming the yellow trioxide, Bi

2O

3.[21][44] When molten, at temperatures above 710 °C, this oxide corrodes any metal oxide and even platinum.[33] On reaction with a base, it forms two series of oxyanions: BiO−

2, which is polymeric and forms linear chains, and BiO3−

3. The anion in Li

3BiO

3 is a cubic octameric anion, Bi

8O24−

24, whereas the anion in Na

3BiO

3 is tetrameric.[45]