Какая по счету Венера от Солнца?

Венера – самый яркий объект на небосводе после Солнца и Луны. Какое место она занимает в Солнечной системе?

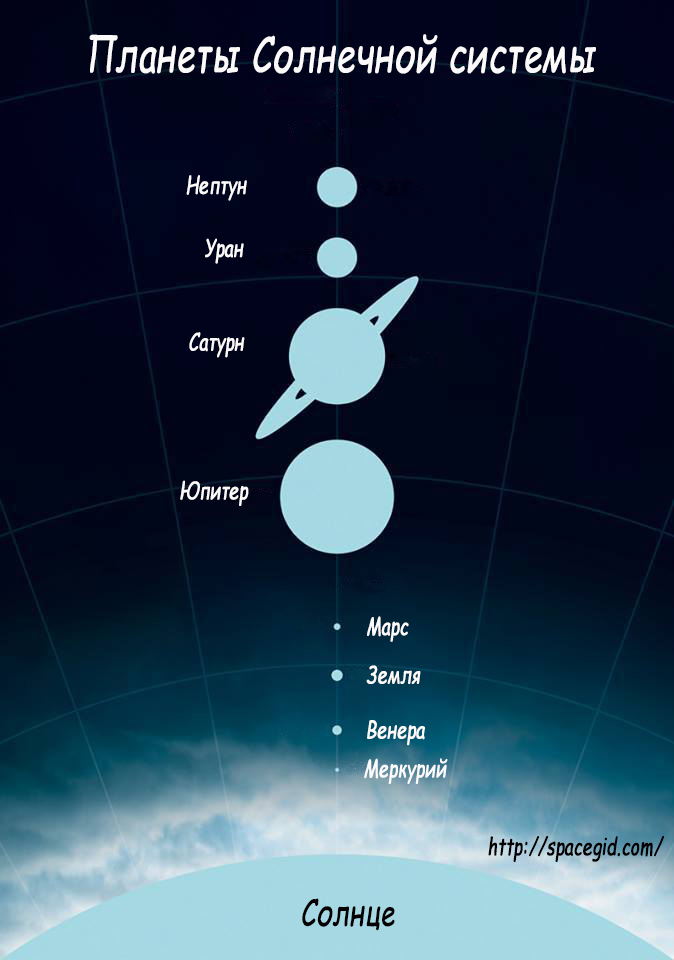

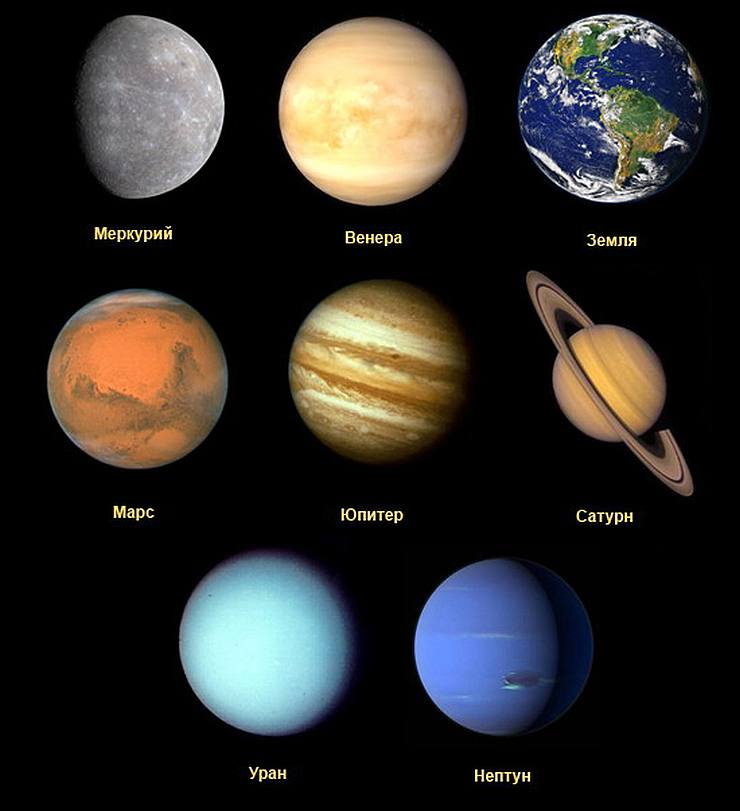

Венера – вторая планета от Солнца. Она находится между Меркурием (1-ой планетой) и Землей (3-ей планетой). Венерианская орбита – это эллипс, очень близкий к окружности. Расстояние между планетой и Солнцем изменяется от 107,4 до 108,8 млн км.

Венеру часто называют «сестрой Земли». Дело в том, что две эти планеты обладают рядом схожих черт. Если радиус Земли составляет 6371 км, то у Венеры его величина составляет 6051 км. Масса Венеры составляет 81% от земной массы, а объем – 85%. Близки друг к другу и значения ускорения свободного падения 8,87 м/с2 на Венере и 9,78 м/с2 на Земле. Все другие планеты Солнечной системы либо в разы больше, либо в разы меньше Земли по массе и объему.

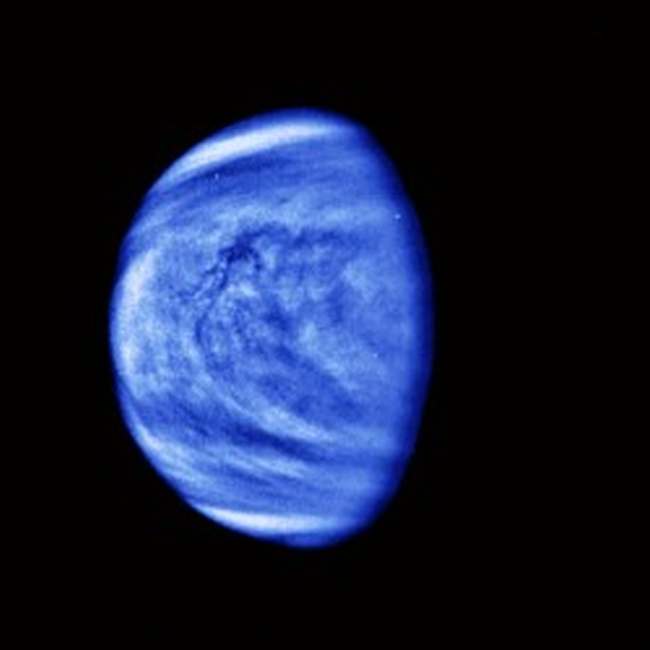

Хотя Венера и располагается дальше Меркурия от Солнца, именно ей принадлежит статус самой горячей планеты в Солнечной системе. Температура на ее поверхности может подниматься до +477° С, причем ночью она уменьшается незначительно. Такой экстремальный климат связан с тем, что Венера обладает очень плотной атмосферой, давление которой в 100 раз превышает давление у поверхности Земли. Аналогичное давление испытывают корпуса подводных лодок на глубине 900 м.

При этом большая часть атмосферы Венеры (96,5%) – это углекислый газ. Он создает сильнейший парниковый эффект, который и разогревает планету. Если бы венерианская атмосфера была аналогична земной, то температура у поверхности не превышала бы 80° С, то есть на ней могла бы быть жидкая вода и даже жизнь.

Атмосфера также способствует перераспределению тепла, поэтому температура на Венере почти не зависит от времени суток. Кстати, день и ночь меняются на планете очень медленно. На полный оборот вокруг своей оси Венера тратит 243 земных дня. На оборот вокруг звезды она тратит только 224,6 дня. Таким образом, венерианский год оказывается короче венерианских суток!

Список использованных источников

• https://cosmosplanet.ru/solnechnayasistema/venera/kakaya-po-schyotu-venera-ot-solntsa.html • https://spacegid.com/planetyi-nashey-s-vami-solnechnoy-sistemyi.html • https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Венера

Пришелец Инопланетянович

Если не оставишь коммент, то я приду за тобой!!!

Оставить коммент

Не нашли, то что искали? Используйте форму поиска по сайту

Понравилась статья? Оставь комментарий и поделись с друзьями

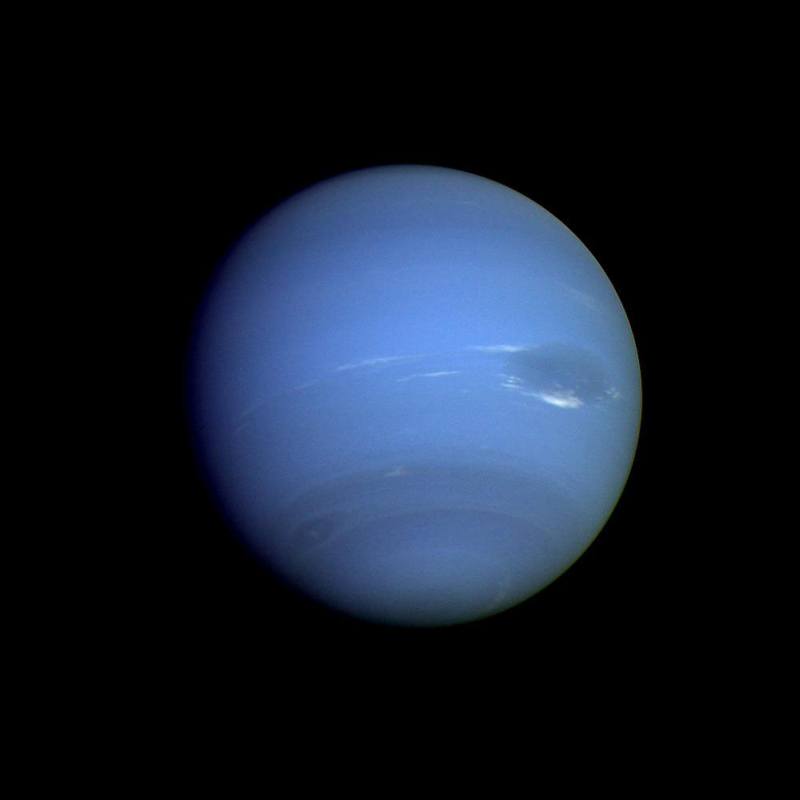

Near-global view of Venus in natural colour, taken by the MESSENGER space probe | ||||||||||||||||

| Designations | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | ( | |||||||||||||||

| Named after | Venus | |||||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Venusian ,[1] rarely Cytherean [2] or Venerean / Venerian [3] | |||||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[5][7] | ||||||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aphelion |

| |||||||||||||||

| Perihelion |

| |||||||||||||||

| Semi-major axis |

| |||||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.006772[4] | |||||||||||||||

| Orbital period (sidereal) |

| |||||||||||||||

| Orbital period (synodic) | 583.92 days[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Average orbital speed | 35.02 km/s | |||||||||||||||

| Mean anomaly | 50.115° | |||||||||||||||

| Inclination |

| |||||||||||||||

| Longitude of ascending node | 76.680°[4] | |||||||||||||||

| Argument of perihelion | 54.884° | |||||||||||||||

| Satellites | None | |||||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean radius |

| |||||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0[8] | |||||||||||||||

| Surface area |

| |||||||||||||||

| Volume |

| |||||||||||||||

| Mass |

| |||||||||||||||

| Mean density | 5.243 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||

| Surface gravity |

| |||||||||||||||

| Escape velocity | 10.36 km/s (6.44 mi/s)[10] | |||||||||||||||

| Synodic rotation period | −116.75 d (retrograde)[11] 1 Venus solar day | |||||||||||||||

| Sidereal rotation period | −243.0226 d (retrograde)[12] | |||||||||||||||

| Equatorial rotation velocity | 6.52 km/h (1.81 m/s) | |||||||||||||||

| Axial tilt | 2.64° (for retrograde rotation) 177.36° (to orbit)[5][note 1] | |||||||||||||||

| North pole right ascension |

| |||||||||||||||

| North pole declination | 67.16° | |||||||||||||||

| Albedo |

| |||||||||||||||

| Temperature | 232 K (−41 °C) (blackbody temperature)[16] | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Surface absorbed dose rate | 2.1×10−6 μGy/h[18] | |||||||||||||||

| Surface equivalent dose rate | 2.2×10−6 μSv/h 0.092–22 μSv/h at the habitable zone[18] | |||||||||||||||

| Apparent magnitude | −4.92 to −2.98[17] | |||||||||||||||

| Angular diameter | 9.7″–66.0″[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[5] | ||||||||||||||||

| Surface pressure | 93 bar (9.3 MPa) 92 atm | |||||||||||||||

| Composition by volume |

| |||||||||||||||

|

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth’s «sister» or «twin» planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth’s sky never far from the Sun, either as morning star or evening star. Aside from the Sun and Moon, Venus is the brightest natural object in Earth’s sky, capable of casting visible shadows on Earth at dark conditions and being visible to the naked eye in broad daylight.[19][20]

Venus is the second largest terrestrial object of the Solar System. It has a surface gravity slightly lower than on Earth and has a very weak induced magnetosphere. The atmosphere of Venus consists mainly of carbon dioxide, and, at the planet’s surface, is the densest and hottest of the atmospheres of the four terrestrial planets. With an atmospheric pressure at the planet’s surface of about 92 times the sea level pressure of Earth and a mean temperature of 737 K (464 °C; 867 °F), the carbon dioxide gas at Venus’s surface is in the supercritical phase of matter. Venus is shrouded by an opaque layer of highly reflective clouds of sulfuric acid, making it the planet with the highest albedo in the Solar System. It may have had water oceans in the past,[21][22] but after these evaporated the temperature rose under a runaway greenhouse effect.[23] The possibility of life on Venus has long been a topic of speculation but convincing evidence has yet to be found.

Like Mercury, Venus does not have any moons.[24] Solar days on Venus, with a length of 117 Earth days,[25] are just about half as long as its solar year, orbiting the Sun every 224.7 Earth days.[26] This Venusian daylength is a product of it rotating against its orbital motion, halving its full sidereal rotation period of 243 Earth days, the longest of all the Solar System planets. Venus and Uranus are the only planets with such a retrograde rotation, making the Sun move in their skies from their western horizon to their eastern. The orbit of Venus around the Sun is the closest to Earth’s orbit, bringing them closer than any other pair of planets. This occurs during inferior conjunction with a synodic period of 1.6 years. However, Mercury is more frequently the closest to each.

The orbits of Venus and Earth result in the lowest gravitational potential difference and lowest delta-v needed to transfer between them than to any other planet. This has made Venus a prime target for early interplanetary exploration. It was the first planet beyond Earth that spacecraft were sent to, starting with Venera 1 in 1961, and the first planet to be reached, impacted and in 1970 successfully landed on by Venera 7. As one of the brightest objects in the sky, Venus has been a major fixture in human culture for as long as records have existed. It has been made sacred to gods of many cultures, gaining its mainly used name from the Roman goddess of love and beauty which it is associated with. Furthermore it has been a prime inspiration for writers, poets and scholars. Venus was the first planet to have its motions plotted across the sky, as early as the second millennium BCE.[27] Plans for better exploration with rovers or atmospheric missions, potentially crewed, at levels with almost Earth-like conditions have been proposed.

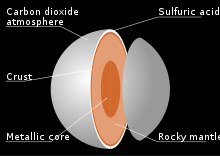

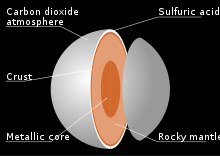

Physical characteristics

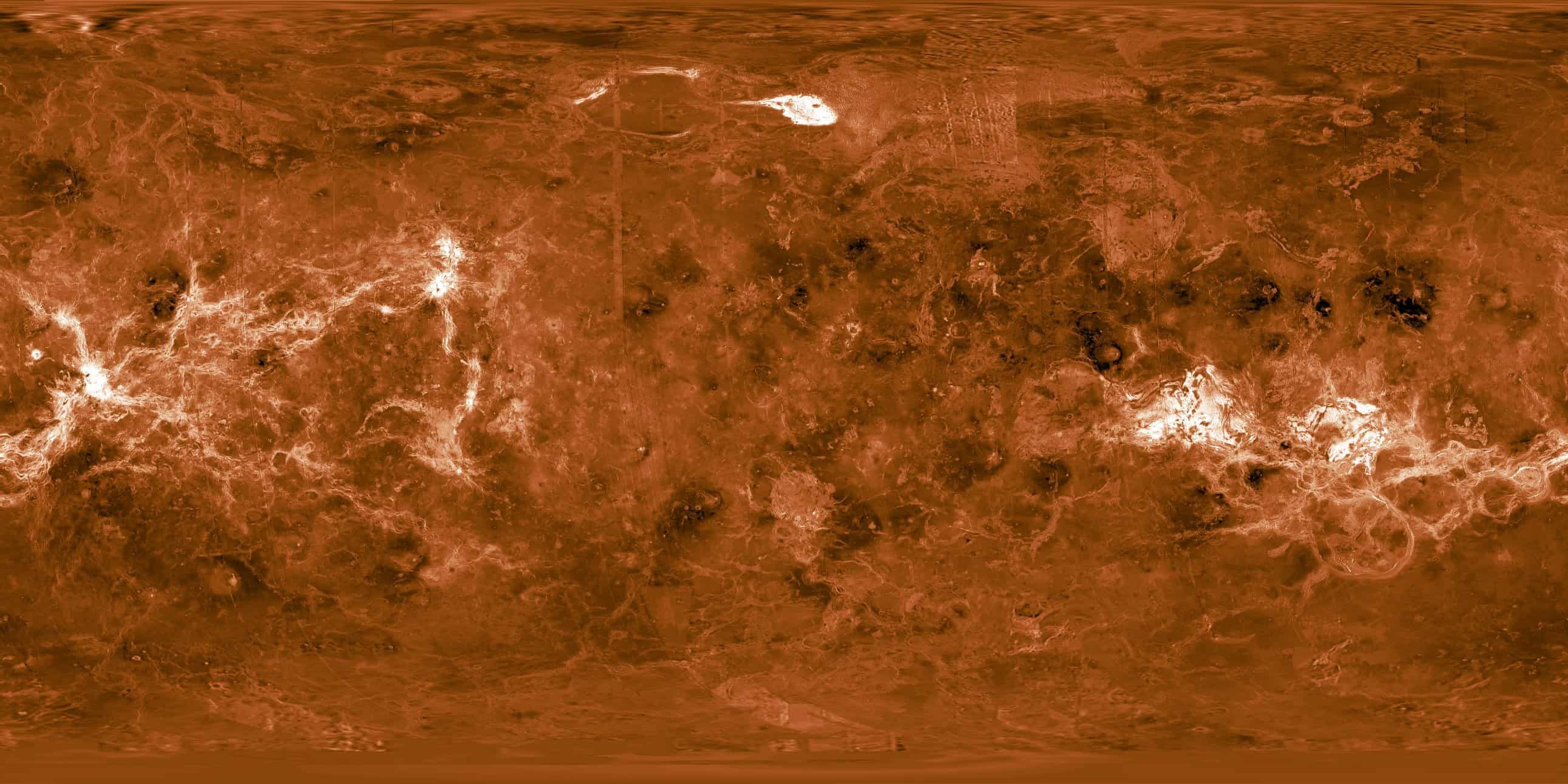

Size comparison of Earth and Venus (radar surface map)

Venus is one of the four terrestrial planets in the Solar System, meaning that it is a rocky body like Earth. It is similar to Earth in size and mass and is often described as Earth’s «sister» or «twin».[28] The diameter of Venus is 12,103.6 km (7,520.8 mi)—only 638.4 km (396.7 mi) less than Earth’s—and its mass is 81.5% of Earth’s. Conditions on the Venusian surface differ radically from those on Earth because its dense atmosphere is 96.5% carbon dioxide, with most of the remaining 3.5% being nitrogen.[29] The surface pressure is 9.3 megapascals (93 bars), and the average surface temperature is 737 K (464 °C; 867 °F), above the critical points of both major constituents and making the surface atmosphere a supercritical fluid.

Atmosphere and climate

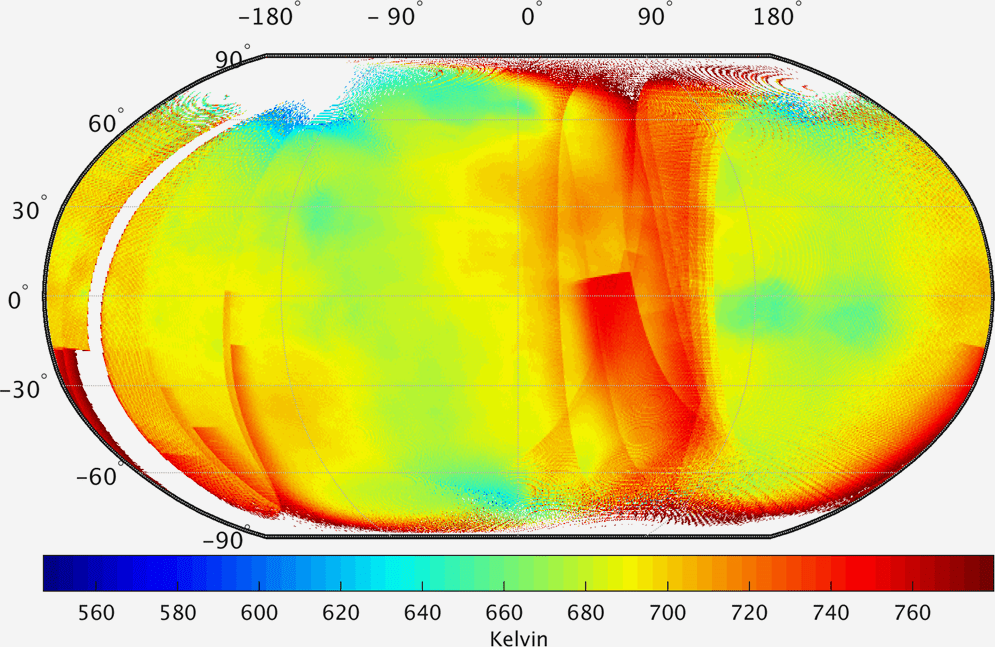

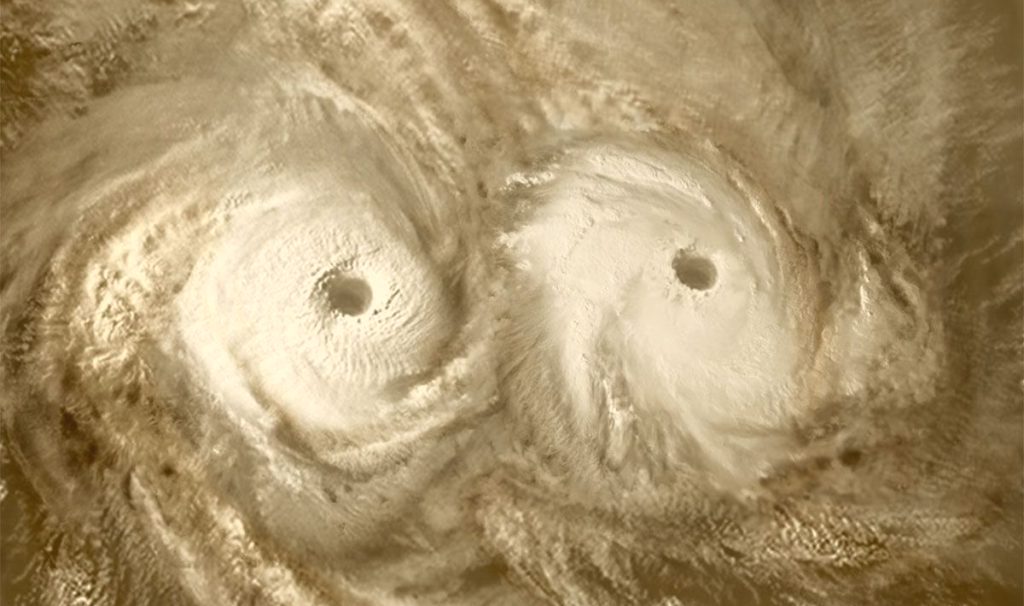

Cloud structure of the Venusian atmosphere in the ultraviolet band

Venus has an extremely dense atmosphere composed of 96.5% carbon dioxide, 3.5% nitrogen—both exist as supercritical fluids at the planet’s surface—and traces of other gases including sulfur dioxide.[30] The mass of its atmosphere is 92 times that of Earth’s, whereas the pressure at its surface is about 93 times that at Earth’s—a pressure equivalent to that at a depth of nearly 1 km (5⁄8 mi) under Earth’s oceans. The density at the surface is 65 kg/m3 (4.1 lb/cu ft), 6.5% that of water or 50 times as dense as Earth’s atmosphere at 293 K (20 °C; 68 °F) at sea level. The CO2-rich atmosphere generates the strongest greenhouse effect in the Solar System, creating surface temperatures of at least 735 K (462 °C; 864 °F).[26][31] This makes the Venusian surface hotter than Mercury’s, which has a minimum surface temperature of 53 K (−220 °C; −364 °F) and maximum surface temperature of 700 K (427 °C; 801 °F),[32][33] even though Venus is nearly twice Mercury’s distance from the Sun and thus receives only 25% of Mercury’s solar irradiance. Because of its runaway greenhouse effect, Venus has been identified by scientists such as Carl Sagan as a warning and research object linked to climate change on Earth.[34]

| Type | Surface Temperature |

|---|---|

| Maximum | 900 °F (482 °C) |

| Normal | 847 °F (453 °C) |

| Minimum | 820 °F (438 °C) |

Venus’s atmosphere is extremely rich in primordial noble gases compared to that of Earth.[36] This enrichment indicates an early divergence from Earth in evolution. An unusually large comet impact[37] or accretion of a more massive primary atmosphere from solar nebula[38] have been proposed to explain the enrichment. However, the atmosphere is also depleted of radiogenic argon, a proxy to mantle degassing, suggesting an early shutdown of major magmatism.[39][40]

Studies[which?] have suggested that billions of years ago, Venus’s atmosphere could have been much more like the one surrounding the early Earth, and that there may have been substantial quantities of liquid water on the surface. After a period of 600 million to several billion years,[41] solar forcing from rising luminosity of the Sun caused the evaporation of the original water. A runaway greenhouse effect was created once a critical level of greenhouse gases (including water) was added to its atmosphere.[42] Although the surface conditions on Venus are no longer hospitable to any Earth-like life that may have formed before this event, there is speculation on the possibility that life exists in the upper cloud layers of Venus, 50 km (30 mi) up from the surface, where the temperature ranges between 303 and 353 K (30 and 80 °C; 86 and 176 °F) but the environment is acidic.[43][44][45] The putative detection of an absorption line of phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere, with no known pathway for abiotic production, led to speculation in September 2020 that there could be extant life currently present in the atmosphere.[46][47] Later research attributed the spectroscopic signal that was interpreted as phosphine to sulfur dioxide,[48] or found that in fact there was no absorption line.[49][50]

Thermal inertia and the transfer of heat by winds in the lower atmosphere mean that the temperature of Venus’s surface does not vary significantly between the planet’s two hemispheres, those facing and not facing the Sun, despite Venus’s extremely slow rotation. Winds at the surface are slow, moving at a few kilometres per hour, but because of the high density of the atmosphere at the surface, they exert a significant amount of force against obstructions, and transport dust and small stones across the surface. This alone would make it difficult for a human to walk through, even without the heat, pressure, and lack of oxygen.[51]

Above the dense CO2 layer are thick clouds, consisting mainly of sulfuric acid, which is formed by sulfur dioxide and water through a chemical reaction resulting in sulfuric acid hydrate. Additionally, the clouds consist of approximately 1% ferric chloride.[52][53] Other possible constituents of the cloud particles are ferric sulfate, aluminium chloride and phosphoric anhydride. Clouds at different levels have different compositions and particle size distributions.[52] These clouds reflect and scatter about 90% of the sunlight that falls on them back into space, and prevent visual observation of Venus’s surface. The permanent cloud cover means that although Venus is closer than Earth to the Sun, it receives less sunlight on the ground. Strong 300 km/h (185 mph) winds at the cloud tops go around Venus about every four to five Earth days.[54] Winds on Venus move at up to 60 times the speed of its rotation, whereas Earth’s fastest winds are only 10–20% rotation speed.[55]

The surface of Venus is effectively isothermal; it retains a constant temperature not only between the two hemispheres but between the equator and the poles.[5][56] Venus’s minute axial tilt—less than 3°, compared to 23° on Earth—also minimises seasonal temperature variation.[57] Altitude is one of the few factors that affect Venusian temperature. The highest point on Venus, Maxwell Montes, is therefore the coolest point on Venus, with a temperature of about 655 K (380 °C; 715 °F) and an atmospheric pressure of about 4.5 MPa (45 bar).[58][59] In 1995, the Magellan spacecraft imaged a highly reflective substance at the tops of the highest mountain peaks that bore a strong resemblance to terrestrial snow. This substance likely formed from a similar process to snow, albeit at a far higher temperature. Too volatile to condense on the surface, it rose in gaseous form to higher elevations, where it is cooler and could precipitate. The identity of this substance is not known with certainty, but speculation has ranged from elemental tellurium to lead sulfide (galena).[60]

Although Venus has no seasons as such, in 2019, astronomers identified a cyclical variation in sunlight absorption by the atmosphere, possibly caused by opaque, absorbing particles suspended in the upper clouds. The variation causes observed changes in the speed of Venus’s zonal winds and appears to rise and fall in time with the Sun’s 11-year sunspot cycle.[61]

The existence of lightning in the atmosphere of Venus has been controversial[62] since the first suspected bursts were detected by the Soviet Venera probes.[63][64][65] In 2006–07, Venus Express clearly detected whistler mode waves, the signatures of lightning. Their intermittent appearance indicates a pattern associated with weather activity. According to these measurements, the lightning rate is at least half of that on Earth,[66] however other instruments have not detected lightning at all.[62] The origin of any lightning remains unclear, but could originate from the clouds or volcanoes.

In 2007, Venus Express discovered that a huge double atmospheric vortex exists at the south pole.[67][68] Venus Express also discovered, in 2011, that an ozone layer exists high in the atmosphere of Venus.[69] On 29 January 2013, ESA scientists reported that the ionosphere of Venus streams outwards in a manner similar to «the ion tail seen streaming from a comet under similar conditions.»[70][71]

In December 2015, and to a lesser extent in April and May 2016, researchers working on Japan’s Akatsuki mission observed bow shapes in the atmosphere of Venus. This was considered direct evidence of the existence of perhaps the largest stationary gravity waves in the solar system.[72][73][74]

Green colour—water vapour, red—carbon dioxide, WN—wavenumber (other colours have different meanings, shorter wavelengths on the right, longer on the left).

Geography

180-degree panorama of Venus’s surface from the Soviet Venera 9 lander, 1975. Black-and-white image of barren, black, slate-like rocks against a flat sky. The ground and the probe are the focus.

The Venusian surface was a subject of speculation until some of its secrets were revealed by planetary science in the 20th century. Venera landers in 1975 and 1982 returned images of a surface covered in sediment and relatively angular rocks.[77] The surface was mapped in detail by Magellan in 1990–91. The ground shows evidence of extensive volcanism, and the sulfur in the atmosphere may indicate that there have been recent eruptions.[78][79]

About 80% of the Venusian surface is covered by smooth, volcanic plains, consisting of 70% plains with wrinkle ridges and 10% smooth or lobate plains.[80] Two highland «continents» make up the rest of its surface area, one lying in the planet’s northern hemisphere and the other just south of the equator. The northern continent is called Ishtar Terra after Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love, and is about the size of Australia. Maxwell Montes, the highest mountain on Venus, lies on Ishtar Terra. Its peak is 11 km (7 mi) above the Venusian average surface elevation.[81] The southern continent is called Aphrodite Terra, after the Greek goddess of love, and is the larger of the two highland regions at roughly the size of South America. A network of fractures and faults covers much of this area.[82]

The absence of evidence of lava flow accompanying any of the visible calderas remains an enigma. The planet has few impact craters, demonstrating that the surface is relatively young, at 300–600 million years old.[83][84] Venus has some unique surface features in addition to the impact craters, mountains, and valleys commonly found on rocky planets. Among these are flat-topped volcanic features called «farra», which look somewhat like pancakes and range in size from 20 to 50 km (12 to 31 mi) across, and from 100 to 1,000 m (330 to 3,280 ft) high; radial, star-like fracture systems called «novae»; features with both radial and concentric fractures resembling spider webs, known as «arachnoids»; and «coronae», circular rings of fractures sometimes surrounded by a depression. These features are volcanic in origin.[85]

Most Venusian surface features are named after historical and mythological women.[86] Exceptions are Maxwell Montes, named after James Clerk Maxwell, and highland regions Alpha Regio, Beta Regio, and Ovda Regio. The last three features were named before the current system was adopted by the International Astronomical Union, the body which oversees planetary nomenclature.[87]

The longitude of physical features on Venus are expressed relative to its prime meridian. The original prime meridian passed through the radar-bright spot at the centre of the oval feature Eve, located south of Alpha Regio.[88] After the Venera missions were completed, the prime meridian was redefined to pass through the central peak in the crater Ariadne on Sedna Planitia.[89][90]

The stratigraphically oldest tessera terrains have consistently lower thermal emissivity than the surrounding basaltic plains measured by Venus Express and Magellan, indicating a different, possibly a more felsic, mineral assemblage.[21][91] The mechanism to generate a large amount of felsic crust usually requires the presence of water ocean and plate tectonics, implying that habitable condition had existed on early Venus. However, the nature of tessera terrains is far from certain.[92]

Volcanism

Much of the Venusian surface appears to have been shaped by volcanic activity. Venus has several times as many volcanoes as Earth, and it has 167 large volcanoes that are over 100 km (60 mi) across. The only volcanic complex of this size on Earth is the Big Island of Hawaii.[85]: 154 This is not because Venus is more volcanically active than Earth, but because its crust is older and is not subject to the same erosion process. Earth’s oceanic crust is continually recycled by subduction at the boundaries of tectonic plates, and has an average age of about a hundred million years,[93] whereas the Venusian surface is estimated to be 300–600 million years old.[83][85]

Several lines of evidence point to ongoing volcanic activity on Venus. Sulfur dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere dropped by a factor of 10 between 1978 and 1986, jumped in 2006, and again declined 10-fold.[94] This may mean that levels had been boosted several times by large volcanic eruptions.[95][96] It has also been suggested that Venusian lightning (discussed below) could originate from volcanic activity (i.e. volcanic lightning). In January 2020, astronomers reported evidence that suggests that Venus is currently volcanically active, specifically the detection of olivine, a volcanic product that would weather quickly on the planet’s surface.[97][98]

In 2008 and 2009, the first direct evidence for ongoing volcanism was observed by Venus Express, in the form of four transient localized infrared hot spots within the rift zone Ganis Chasma,[99][n 1] near the shield volcano Maat Mons. Three of the spots were observed in more than one successive orbit. These spots are thought to represent lava freshly released by volcanic eruptions.[100][101] The actual temperatures are not known, because the size of the hot spots could not be measured, but are likely to have been in the 800–1,100 K (527–827 °C; 980–1,520 °F) range, relative to a normal temperature of 740 K (467 °C; 872 °F).[102]

Craters

Impact craters on the surface of Venus (false-colour image reconstructed from radar data)

Almost a thousand impact craters on Venus are evenly distributed across its surface. On other cratered bodies, such as Earth and the Moon, craters show a range of states of degradation. On the Moon, degradation is caused by subsequent impacts, whereas on Earth it is caused by wind and rain erosion. On Venus, about 85% of the craters are in pristine condition. The number of craters, together with their well-preserved condition, indicates the planet underwent a global resurfacing event 300–600 million years ago,[83][84] followed by a decay in volcanism.[103] Whereas Earth’s crust is in continuous motion, Venus is thought to be unable to sustain such a process. Without plate tectonics to dissipate heat from its mantle, Venus instead undergoes a cyclical process in which mantle temperatures rise until they reach a critical level that weakens the crust. Then, over a period of about 100 million years, subduction occurs on an enormous scale, completely recycling the crust.[85]

Venusian craters range from 3 to 280 km (2 to 174 mi) in diameter. No craters are smaller than 3 km, because of the effects of the dense atmosphere on incoming objects. Objects with less than a certain kinetic energy are slowed so much by the atmosphere that they do not create an impact crater.[104] Incoming projectiles less than 50 m (160 ft) in diameter will fragment and burn up in the atmosphere before reaching the ground.[105]

Internal structure

Without seismic data or knowledge of its moment of inertia, little direct information is available about the internal structure and geochemistry of Venus.[106] The similarity in size and density between Venus and Earth suggests they share a similar internal structure: a core, mantle, and crust. Like that of Earth, the Venusian core is most likely at least partially liquid because the two planets have been cooling at about the same rate,[107] although a completely solid core cannot be ruled out.[108] The slightly smaller size of Venus means pressures are 24% lower in its deep interior than Earth’s.[109] The predicted values for the moment of inertia based on planetary models suggest a core radius of 2,900–3,450 km.[108] This is in line with the first observation-based estimate of 3,500 km.[110]

The principal difference between the two planets is the lack of evidence for plate tectonics on Venus, possibly because its crust is too strong to subduct without water to make it less viscous. This results in reduced heat loss from the planet, preventing it from cooling and providing a likely explanation for its lack of an internally generated magnetic field.[111]

Instead, Venus may lose its internal heat in periodic major resurfacing events.[83]

Magnetic field and core

In 1967, Venera 4 found Venus’s magnetic field to be much weaker than that of Earth. This magnetic field is induced by an interaction between the ionosphere and the solar wind,[112][113] rather than by an internal dynamo as in the Earth’s core. Venus’s small induced magnetosphere provides negligible protection to the atmosphere against cosmic radiation.

The lack of an intrinsic magnetic field at Venus was surprising, given that it is similar to Earth in size and was expected also to contain a dynamo at its core. A dynamo requires three things: a conducting liquid, rotation, and convection. The core is thought to be electrically conductive and, although its rotation is often thought to be too slow, simulations show it is adequate to produce a dynamo.[114][115] This implies that the dynamo is missing because of a lack of convection in Venus’s core. On Earth, convection occurs in the liquid outer layer of the core because the bottom of the liquid layer is much higher in temperature than the top. On Venus, a global resurfacing event may have shut down plate tectonics and led to a reduced heat flux through the crust. This insulating effect would cause the mantle temperature to increase, thereby reducing the heat flux out of the core. As a result, no internal geodynamo is available to drive a magnetic field. Instead, the heat from the core is reheating the crust.[116]

One possibility is that Venus has no solid inner core,[117] or that its core is not cooling, so that the entire liquid part of the core is at approximately the same temperature. Another possibility is that its core has already completely solidified. The state of the core is highly dependent on the concentration of sulfur, which is unknown at present.[116]

The weak magnetosphere around Venus means that the solar wind is interacting directly with its outer atmosphere. Here, ions of hydrogen and oxygen are being created by the dissociation of water molecules from ultraviolet radiation. The solar wind then supplies energy that gives some of these ions sufficient velocity to escape Venus’s gravity field. This erosion process results in a steady loss of low-mass hydrogen, helium, and oxygen ions, whereas higher-mass molecules, such as carbon dioxide, are more likely to be retained. Atmospheric erosion by the solar wind could have led to the loss of most of Venus’s water during the first billion years after it formed.[118] However, the planet may have retained a dynamo for its first 2–3 billion years, so the water loss may have occurred more recently.[119] The erosion has increased the ratio of higher-mass deuterium to lower-mass hydrogen in the atmosphere 100 times compared to the rest of the solar system.[120]

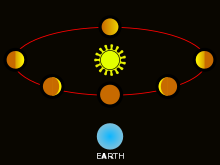

Orbit and rotation

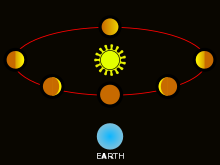

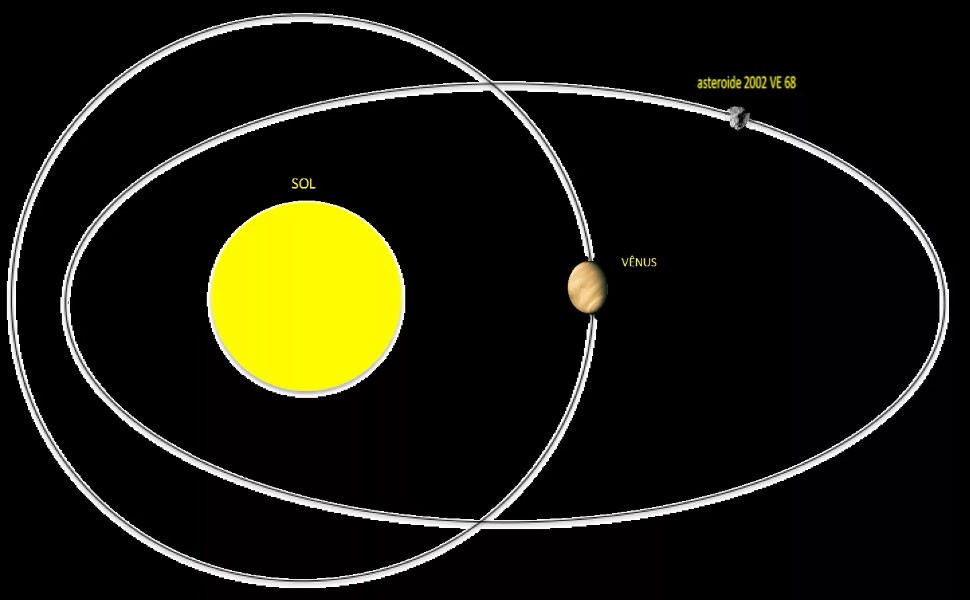

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, making a full orbit in about 224 days

Venus orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 0.72 AU (108 million km; 67 million mi), and completes an orbit every 224.7 days. Although all planetary orbits are elliptical, Venus’s orbit is currently the closest to circular, with an eccentricity of less than 0.01.[5] Simulations of the early solar system orbital dynamics have shown that the eccentricity of the Venus orbit may have been substantially larger in the past, reaching values as high as 0.31 and possibly impacting the early climate evolution.[121] The current near-circular orbit of Venus means that when Venus lies between Earth and the Sun in inferior conjunction, it makes the closest approach to Earth of any planet at an average distance of 41 million km (25 million mi).[5][n 2][122]

The planet reaches at a orbital resonance of 8 Earth orbits to 13 Venus orbits,[123] inferior conjunctions at a synodic period of 584 days, on average.[5] Because of the decreasing eccentricity of Earth’s orbit, the minimum distances will become greater over tens of thousands of years. From the year 1 to 5383, there are 526 approaches less than 40 million km (25 million mi); then, there are none for about 60,158 years.[124] While Venus approaches Earth the closest, Mercury approaches Earth more often the closest of all planets.[125] That said, Venus and Earth still have the lowest gravitational potential difference between them than to any other planet, needing the lowest delta-v to transfer between them, than to any other planet from them.[126][127]

All the planets in the Solar System orbit the Sun in an anticlockwise direction as viewed from above Earth’s north pole. Most planets also rotate on their axes in an anticlockwise direction, but Venus rotates clockwise in retrograde rotation once every 243 Earth days—the slowest rotation of any planet. Because its rotation is so slow, Venus is very close to spherical.[128] A Venusian sidereal day thus lasts longer than a Venusian year (243 versus 224.7 Earth days). Venus’s equator rotates at 6.52 km/h (4.05 mph), whereas Earth’s rotates at 1,674.4 km/h (1,040.4 mph).[132][133] Venus’s rotation period measured with Magellan spacecraft data over a 500-day period is smaller than the rotation period measured during the 16-year period between the Magellan spacecraft and Venus Express visits, with a difference of about 6.5 minutes.[134] Because of the retrograde rotation, the length of a solar day on Venus is significantly shorter than the sidereal day, at 116.75 Earth days (making the Venusian solar day shorter than Mercury’s 176 Earth days — the 116-day figure is extremely close to the average number of days it takes Mercury to slip underneath the Earth in its orbit).[11] One Venusian year is about 1.92 Venusian solar days.[135] To an observer on the surface of Venus, the Sun would rise in the west and set in the east,[135] although Venus’s opaque clouds prevent observing the Sun from the planet’s surface.[136]

Venus may have formed from the solar nebula with a different rotation period and obliquity, reaching its current state because of chaotic spin changes caused by planetary perturbations and tidal effects on its dense atmosphere, a change that would have occurred over the course of billions of years. The rotation period of Venus may represent an equilibrium state between tidal locking to the Sun’s gravitation, which tends to slow rotation, and an atmospheric tide created by solar heating of the thick Venusian atmosphere.[137][138]

The 584-day average interval between successive close approaches to Earth is almost exactly equal to 5 Venusian solar days (5.001444 to be precise),[139] but the hypothesis of a spin-orbit resonance with Earth has been discounted.[140]

Venus has no natural satellites.[141] It has several trojan asteroids: the quasi-satellite 2002 VE68[142][143] and two other temporary trojans, 2001 CK32 and 2012 XE133.[144] In the 17th century, Giovanni Cassini reported a moon orbiting Venus, which was named Neith and numerous sightings were reported over the following 200 years, but most were determined to be stars in the vicinity. Alex Alemi’s and David Stevenson’s 2006 study of models of the early Solar System at the California Institute of Technology shows Venus likely had at least one moon created by a huge impact event billions of years ago.[145] About 10 million years later, according to the study, another impact reversed the planet’s spin direction and caused the Venusian moon gradually to spiral inward until it collided with Venus.[146] If later impacts created moons, these were removed in the same way. An alternative explanation for the lack of satellites is the effect of strong solar tides, which can destabilize large satellites orbiting the inner terrestrial planets.[141]

Observability

Venus, pictured center-right, is always brighter than all other planets or stars at their maximal brightness, as seen from Earth. Jupiter is visible at the top of the image.

To the naked eye, Venus appears as a white point of light brighter than any other planet or star (apart from the Sun).[147] The planet’s mean apparent magnitude is −4.14 with a standard deviation of 0.31.[17] The brightest magnitude occurs during crescent phase about one month before or after inferior conjunction. Venus fades to about magnitude −3 when it is backlit by the Sun.[148] The planet is bright enough to be seen in broad daylight,[149] but is more easily visible when the Sun is low on the horizon or setting. As an inferior planet, it always lies within about 47° of the Sun.[150]

Venus «overtakes» Earth every 584 days as it orbits the Sun.[5] As it does so, it changes from the «Evening Star», visible after sunset, to the «Morning Star», visible before sunrise. Although Mercury, the other inferior planet, reaches a maximum elongation of only 28° and is often difficult to discern in twilight, Venus is hard to miss when it is at its brightest. Its greater maximum elongation means it is visible in dark skies long after sunset. As the brightest point-like object in the sky, Venus is a commonly misreported «unidentified flying object».[151]

Phases

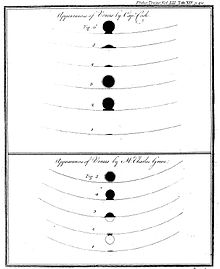

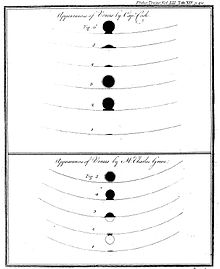

The phases of Venus and evolution of its apparent diameter

As it orbits the Sun, Venus displays phases like those of the Moon in a telescopic view. The planet appears as a small and «full» disc when it is on the opposite side of the Sun (at superior conjunction). Venus shows a larger disc and «quarter phase» at its maximum elongations from the Sun, and appears its brightest in the night sky. The planet presents a much larger thin «crescent» in telescopic views as it passes along the near side between Earth and the Sun. Venus displays its largest size and «new phase» when it is between Earth and the Sun (at inferior conjunction). Its atmosphere is visible through telescopes by the halo of sunlight refracted around it.[150] The phases are clearly visible in a 4″ telescope.

Daylight apparitions

Naked-eye observations of Venus during daylight hours exist in several anecdotes and records. Astronomer Edmund Halley calculated its maximum naked eye brightness in 1716, when many Londoners were alarmed by its appearance in the daytime. French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte once witnessed a daytime apparition of the planet while at a reception in Luxembourg.[152] Another historical daytime observation of the planet took place during the inauguration of the American president Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C., on 4 March 1865.[153] Although naked eye visibility of Venus’s phases is disputed, records exist of observations of its crescent.[154]

Transits

The Venusian orbit is slightly inclined relative to Earth’s orbit; thus, when the planet passes between Earth and the Sun, it usually does not cross the face of the Sun. Transits of Venus occur when the planet’s inferior conjunction coincides with its presence in the plane of Earth’s orbit. Transits of Venus occur in cycles of 243 years with the current pattern of transits being pairs of transits separated by eight years, at intervals of about 105.5 years or 121.5 years—a pattern first discovered in 1639 by the English astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks.[155]

The latest pair was June 8, 2004 and June 5–6, 2012. The transit could be watched live from many online outlets or observed locally with the right equipment and conditions.[156]

The preceding pair of transits occurred in December 1874 and December 1882; the following pair will occur in December 2117 and December 2125.[157] The 1874 transit is the subject of the oldest film known, the 1874 Passage de Venus. Historically, transits of Venus were important, because they allowed astronomers to determine the size of the astronomical unit, and hence the size of the Solar System as shown by Horrocks in 1639.[158] Captain Cook’s exploration of the east coast of Australia came after he had sailed to Tahiti in 1768 to observe a transit of Venus.[159][160]

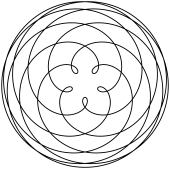

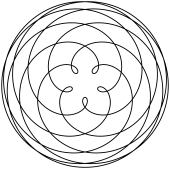

Pentagram of Venus

The pentagram of Venus. Earth is positioned at the centre of the diagram, and the curve represents the direction and distance of Venus as a function of time.

The pentagram of Venus is the path that Venus makes as observed from Earth. Successive inferior conjunctions of Venus repeat with a orbital resonance of 13:8 (Earth orbits eight times for every 13 orbits of Venus), shifting 144° upon sequential inferior conjunctions. The 13:8 ratio is approximate. 8/13 is approximately 0.61538 while Venus orbits the Sun in 0.61519 years.[161] The pentagram of Venus is sometimes also referred to as the petals of Venus due to the path’s visual similarity to a flower.[162]

Ashen light

A long-standing mystery of Venus observations is the so-called ashen light—an apparent weak illumination of its dark side, seen when the planet is in the crescent phase. The first claimed observation of ashen light was made in 1643, but the existence of the illumination has never been reliably confirmed. Observers have speculated it may result from electrical activity in the Venusian atmosphere, but it could be illusory, resulting from the physiological effect of observing a bright, crescent-shaped object.[163][64] The ashen light has often been sighted when Venus is in the evening sky, when the evening terminator of the planet is towards to Earth.

Observation and exploration

Early observation

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as a single entity;[164] instead, they assumed it to be two separate stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star.[164] Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period and the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa from the First Babylonian dynasty indicate that the ancient Sumerians already knew that the morning and evening stars were the same celestial object.[165][164][166] In the Old Babylonian period, the planet Venus was known as Ninsi’anna, and later as Dilbat.[167] The name «Ninsi’anna» translates to «divine lady, illumination of heaven», which refers to Venus as the brightest visible «star». Earlier spellings of the name were written with the cuneiform sign si4 (= SU, meaning «to be red»), and the original meaning may have been «divine lady of the redness of heaven», in reference to the colour of the morning and evening sky.[168]

The Chinese historically referred to the morning Venus as «the Great White» (Tàibái 太白) or «the Opener (Starter) of Brightness» (Qǐmíng 啟明), and the evening Venus as «the Excellent West One» (Chánggēng 長庚).[169]

The ancient Greeks also initially believed Venus to be two separate stars: Phosphorus, the morning star, and Hesperus, the evening star. Pliny the Elder credited the realization that they were a single object to Pythagoras in the sixth century BC,[170] while Diogenes Laërtius argued that Parmenides was probably responsible for this discovery.[171] Though they recognized Venus as a single object, the ancient Romans continued to designate the morning aspect of Venus as Lucifer, literally «Light-Bringer», and the evening aspect as Vesper,[172] both of which are literal translations of their traditional Greek names.

In the second century, in his astronomical treatise Almagest, Ptolemy theorized that both Mercury and Venus are located between the Sun and the Earth. The 11th-century Persian astronomer Avicenna claimed to have observed the transit of Venus,[173] which later astronomers took as confirmation of Ptolemy’s theory.[174] In the 12th century, the Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah observed «two planets as black spots on the face of the Sun»; these were thought to be the transits of Venus and Mercury by 13th-century Maragha astronomer Qotb al-Din Shirazi, though this cannot be true as there were no Venus transits in Ibn Bajjah’s lifetime.[175][n 3]

Galileo’s discovery that Venus showed phases (although remaining near the Sun in Earth’s sky) proved that it orbits the Sun and not Earth.

When the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei first observed the planet in the early 17th century, he found it showed phases like the Moon, varying from crescent to gibbous to full and vice versa. When Venus is furthest from the Sun in the sky, it shows a half-lit phase, and when it is closest to the Sun in the sky, it shows as a crescent or full phase. This could be possible only if Venus orbited the Sun, and this was among the first observations to clearly contradict the Ptolemaic geocentric model that the Solar System was concentric and centred on Earth.[178][179]

The 1639 transit of Venus was accurately predicted by Jeremiah Horrocks and observed by him and his friend, William Crabtree, at each of their respective homes, on 4 December 1639 (24 November under the Julian calendar in use at that time).[180]

The atmosphere of Venus was discovered in 1761 by Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov.[181][182] Venus’s atmosphere was observed in 1790 by German astronomer Johann Schröter. Schröter found when the planet was a thin crescent, the cusps extended through more than 180°. He correctly surmised this was due to scattering of sunlight in a dense atmosphere. Later, American astronomer Chester Smith Lyman observed a complete ring around the dark side of the planet when it was at inferior conjunction, providing further evidence for an atmosphere.[183] The atmosphere complicated efforts to determine a rotation period for the planet, and observers such as Italian-born astronomer Giovanni Cassini and Schröter incorrectly estimated periods of about 24 h from the motions of markings on the planet’s apparent surface.[184]

Ground-based research

Modern telescopic view of Venus from Earth’s surface

Little more was discovered about Venus until the 20th century. Its almost featureless disc gave no hint what its surface might be like, and it was only with the development of spectroscopic, radar and ultraviolet observations that more of its secrets were revealed. The first ultraviolet observations were carried out in the 1920s, when Frank E. Ross found that ultraviolet photographs revealed considerable detail that was absent in visible and infrared radiation. He suggested this was due to a dense, yellow lower atmosphere with high cirrus clouds above it.[185]

Spectroscopic observations in the 1900s gave the first clues about the Venusian rotation. Vesto Slipher tried to measure the Doppler shift of light from Venus, but found he could not detect any rotation. He surmised the planet must have a much longer rotation period than had previously been thought.[186] Later work in the 1950s showed the rotation was retrograde. Radar observations of Venus were first carried out in the 1960s, and provided the first measurements of the rotation period, which were close to the modern value.[187]

Radar observations in the 1970s revealed details of the Venusian surface for the first time. Pulses of radio waves were beamed at the planet using the 300 m (1,000 ft) radio telescope at Arecibo Observatory, and the echoes revealed two highly reflective regions, designated the Alpha and Beta regions. The observations also revealed a bright region attributed to mountains, which was called Maxwell Montes.[188] These three features are now the only ones on Venus that do not have female names.[87]

Exploration

The first robotic space probe mission to Venus and any planet was Venera 1 of the Soviet Venera program launched in 1961, though it lost contact en route.[189]

Mockup of the Venera 1 spacecraft

The first successful mission to Venus (as well as the world’s first successful interplanetary mission) was the Mariner 2 mission by the United States, passing on 14 December 1962 at 34,833 km (21,644 mi) above the surface of Venus and gathering data on the planet’s atmosphere.[190][191]

Artist’s impression of Mariner 2, launched in 1962: a skeletal, bottle-shaped spacecraft with a large radio dish on top

On 18 October 1967, the Soviet Venera 4 successfully entered as the first to probe the atmosphere and deployed science experiments. Venera 4 showed the surface temperature was hotter than Mariner 2 had calculated, at almost 500 °C (932 °F), determined that the atmosphere was 95% carbon dioxide (CO

2), and discovered that Venus’s atmosphere was considerably denser than Venera 4‘s designers had anticipated.[192] The joint Venera 4–Mariner 5 data were analysed by a combined Soviet–American science team in a series of colloquia over the following year,[193] in an early example of space cooperation.[194]

On 15 December 1970, Venera 7 became the first spacecraft to soft land on another planet and the first to transmit data from there back to Earth.[195]

In 1974, Mariner 10 swung by Venus to bend its path toward Mercury and took ultraviolet photographs of the clouds, revealing the extraordinarily high wind speeds in the Venusian atmosphere. This was the first interplanetary gravity assist ever used, a technique which would be used by later probes, most notably Voyager 1 and 2.

In 1975, the Soviet Venera 9 and 10 landers transmitted the first images from the surface of Venus, which were in black and white. In 1982 the first colour images of the surface were obtained with the Soviet Venera 13 and 14 landers.

NASA obtained additional data in 1978 with the Pioneer Venus project that consisted of two separate missions:[196] Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Pioneer Venus Multiprobe.[197] The successful Soviet Venera program came to a close in October 1983, when Venera 15 and 16 were placed in orbit to conduct detailed mapping of 25% of Venus’s terrain (from the north pole to 30°N latitude)[198]

Several other missions explored Venus in the 1980s and 1990s, including Vega 1 (1985), Vega 2 (1985), Galileo (1990), Magellan (1994), Cassini–Huygens (1998), and MESSENGER (2006). All except Magellan were gravity assists. Then, Venus Express by the European Space Agency (ESA) entered orbit around Venus in April 2006. Equipped with seven scientific instruments, Venus Express provided unprecedented long-term observation of Venus’s atmosphere. ESA concluded the Venus Express mission in December 2014.[199]

As of 2020, Japan’s Akatsuki is in a highly eccentric orbit around Venus since 7 December 2015, and there are several probing proposals under study by Roscosmos, NASA, ISRO, ESA, and the private sector (e.g. by Rocketlab).

In culture

Venus is a primary feature of the night sky, and so has been of remarkable importance in mythology, astrology and fiction throughout history and in different cultures.

In Sumerian religion, Inanna was associated with the planet Venus.[202][203] Several hymns praise Inanna in her role as the goddess of the planet Venus.[164][203][202] Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has argued that, in many myths, Inanna’s movements may correspond with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky.[164] The discontinuous movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna’s dual nature.[164] In Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld, unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East.[164] An introductory hymn describes Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be, the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West.[164] In Inanna and Shukaletuda and Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld appear to parallel the motion of the planet Venus.[164] In Inanna and Shukaletuda, Shukaletuda is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly searching the eastern and western horizons.[204] In the same myth, while searching for her attacker, Inanna herself makes several movements that correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.[164]

Classical poets such as Homer, Sappho, Ovid and Virgil spoke of the star and its light.[205] Poets such as William Blake, Robert Frost, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Alfred Lord Tennyson and William Wordsworth wrote odes to it.[206]

In Chinese the planet is called Jīn-xīng (金星), the golden planet of the metal element. In India Shukra Graha («the planet Shukra») is named after the powerful saint Shukra. Shukra which is used in Indian Vedic astrology[207] means «clear, pure» or «brightness, clearness» in Sanskrit. One of the nine Navagraha, it is held to affect wealth, pleasure and reproduction; it was the son of Bhrgu, preceptor of the Daityas, and guru of the Asuras.[208] The word Shukra is also associated with semen, or generation. Venus is known as Kejora in Indonesian and Malaysian Malay. Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese cultures refer to the planet literally as the «metal star» (金星), based on the Five elements.[209][210][211][212]

The Maya considered Venus to be the most important celestial body after the Sun and Moon. They called it Chac ek,[213] or Noh Ek‘, «the Great Star».[214] The cycles of Venus were important to their calendar and were described in some of their books such as Maya Codex of Mexico and Dresden Codex.

The Ancient Egyptians and Greeks believed Venus to be two separate bodies, a morning star and an evening star. The Egyptians knew the morning star as Tioumoutiri and the evening star as Ouaiti.[215] The Greeks used the names Phōsphoros (Φωσϕόρος), meaning «light-bringer» (whence the element phosphorus; alternately Ēōsphoros (Ἠωσϕόρος), meaning «dawn-bringer»), for the morning star, and Hesperos (Ἕσπερος), meaning «Western one», for the evening star.[216] Though by the Roman era they were recognized as one celestial object, known as «the star of Venus», the traditional two Greek names continued to be used, though usually translated to Latin as Lūcifer and Vesper.[216][217]

Modern fiction

With the invention of the telescope, the idea that Venus was a physical world and possible destination began to take form.

The impenetrable Venusian cloud cover gave science fiction writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface; all the more so when early observations showed that not only was it similar in size to Earth, it possessed a substantial atmosphere. Closer to the Sun than Earth, the planet was frequently depicted as warmer, but still habitable by humans.[218] The genre reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, at a time when science had revealed some aspects of Venus, but not yet the harsh reality of its surface conditions. Findings from the first missions to Venus showed the reality to be quite different and brought this particular genre to an end.[219] As scientific knowledge of Venus advanced, science fiction authors tried to keep pace, particularly by conjecturing human attempts to terraform Venus.[220]

Symbol

The astronomical symbol for Venus is the same as that used in biology for the female sex: a circle with a small cross beneath.[221][222] The Venus symbol also represents femininity, and in Western alchemy stood for the metal copper.[221][222] Polished copper has been used for mirrors from antiquity, and the symbol for Venus has sometimes been understood to stand for the mirror of the goddess although that is unlikely to be its true origin.[221][222] In the Greek Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 235, the symbols for Venus and Mercury didn’t have the cross-bar on the bottom stroke.[223]

Venus has also been identified as the star in a range of star and crescent depictions and symbols.

Habitability

Speculation on the possibility of life on Venus’s surface decreased significantly after the early 1960s when it became clear that the conditions are extreme compared to those on Earth. Venus’s extreme temperature and atmospheric pressure make water-based life as currently known unlikely.

Some scientists have speculated that thermoacidophilic extremophile microorganisms might exist in the cooler, acidic upper layers of the Venusian atmosphere).[224][225][226] Such speculations go back to 1967, when Carl Sagan and Harold J. Morowitz suggested in a Nature article that tiny objects detected in Venus’s clouds might be organisms similar to Earth’s bacteria (which are of approximately the same size):

- While the surface conditions of Venus make the hypothesis of life there implausible, the clouds of Venus are a different story altogether. As was pointed out some years ago, water, carbon dioxide and sunlight—the prerequisites for photosynthesis—are plentiful in the vicinity of the clouds.[227]

In August 2019, astronomers led by Yeon Joo Lee reported that long-term pattern of absorbance and albedo changes in the atmosphere of the planet Venus caused by «unknown absorbers», which may be chemicals or even large colonies of microorganisms high up in the atmosphere of the planet, affect the climate.[61] Their light absorbance is almost identical to that of micro-organisms in Earth’s clouds. Similar conclusions have been reached by other studies.[228]

In September 2020, a team of astronomers led by Jane Greaves from Cardiff University announced the likely detection of phosphine, a gas not known to be produced by any known chemical processes on the Venusian surface or atmosphere, in the upper levels of the planet’s clouds.[229][230][231][232][233] One proposed source for this phosphine is living organisms.[234] The phosphine was detected at heights of at least 30 miles above the surface, and primarily at mid-latitudes with none detected at the poles. The discovery prompted NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine to publicly call for a new focus on the study of Venus, describing the phosphine find as «the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth».[235][236]

Subsequent analysis of the data-processing used to identify phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus has raised concerns that the detection-line may be an artefact. The use of a 12th-order polynomial fit may have amplified noise and generated a false reading (see Runge’s phenomenon). Observations of the atmosphere of Venus at other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum in which a phosphine absorption line would be expected did not detect phosphine.[237] By late October 2020, re-analysis of data with a proper subtraction of background did not show a statistically significant detection of phosphine.[238][239][240]

Planetary protection

The Committee on Space Research is a scientific organization established by the International Council for Science. Among their responsibilities is the development of recommendations for avoiding interplanetary contamination. For this purpose, space missions are categorized into five groups. Due to the harsh surface environment of Venus, Venus has been under the planetary protection category two.[241] This indicates that there is only a remote chance that spacecraft-borne contamination could compromise investigations.

Human presence

Venus is the place of the very first interplanetary human presence, mediated through robotic missions, with the first successful landings on another planet and extraterrestrial body other than the Moon. Venus was at the beginning of the space age frequently visited by space probes until the 1990s. Currently in orbit is Akatsuki, and the Parker Solar Probe routinely uses Venus for gravity assist maneuvers.[242]

The only nation that has sent lander probes to the surface of Venus has been the Soviet Union,[a] which has been used by Russian officials to call Venus a «Russian planet».[243][244]

Habitation

Artist’s rendering of a NASA HAVOC crewed floating outpost on Venus

While the surface conditions of Venus are very inhospitable, the atmospheric pressure and temperature 50 km above the surface are similar to those at Earth’s surface. With this in mind, Soviet engineer Sergey Zhitomirskiy (Сергей Житомирский, 1929–2004) in 1971[245][246] and more contemporarily NASA aerospace engineer Geoffrey A. Landis in 2003[247] suggested the use of aerostats for crewed exploration and possibly for permanent «floating cities» in the Venusian atmosphere, an alternative to the popular idea of living on planetary surfaces such as Mars.[248][249] Among the many engineering challenges for any human presence in the atmosphere of Venus are the corrosive amounts of sulfuric acid in the atmosphere.[247]

NASA’s High Altitude Venus Operational Concept is a mission concept that proposed a crewed aerostat design.

See also

- Geodynamics of Venus

- Outline of Venus

- Venus zone

- Stats of planets in the Solar System

Notes

- ^ Misstated as «Ganiki Chasma» in the press release and scientific publication.[100]

- ^ It is important to be clear about the meaning of «closeness». In the astronomical literature, the term «closest planets» often refers to the two planets that approach each other the most closely. In other words, the orbits of the two planets approach each other most closely. However, this does not mean that the two planets are closest over time. Essentially because Mercury is closer to the Sun than Venus, Mercury spends more time in proximity to Earth; it could, therefore, be said that Mercury is the planet that is «closest to Earth when averaged over time». However, using this time-average definition of «closeness», it turns out that Mercury is the closest planet to all other planets in the solar system. For that reason, arguably, the proximity-definition is not particularly helpful. An episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme «More or Less» explains the different notions of proximity well.[122]

- ^ Several claims of transit observations made by medieval Islamic astronomers have been shown to be sunspots.[176] Avicenna did not record the date of his observation. There was a transit of Venus within his lifetime, on 24 May 1032, although it is questionable whether it would have been visible from his location.[177]

- ^ The American Pioneer Venus Multiprobe has brought the only non-Soviet probes to enter the atmosphere, as atmospheric entry probes only briefly signals were received from the surface.

References

- ^ «Venusian». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020.

«Venusian». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. - ^ «Cytherean». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Venerean, Venerian». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Simon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). «Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode:1994A&A…282..663S.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Williams, David R. (25 November 2020). «Venus Fact Sheet». NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Souami, D.; Souchay, J. (July 2012). «The solar system’s invariable plane». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: 11. Bibcode:2012A&A…543A.133S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011. A133.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. «HORIZONS Web-Interface for Venus (Major Body=2)». JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2010.—Select «Ephemeris Type: Orbital Elements», «Time Span: 2000-01-01 12:00 to 2000-01-02». («Target Body: Venus» and «Center: Sun» should be defaulted to.) Results are instantaneous osculating values at the precise J2000 epoch.

- ^ a b Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; Archinal, Brent A.; A’Hearn, Michael F.; et al. (2007). «Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006». Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 98 (3): 155–180. Bibcode:2007CeMDA..98..155S. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

- ^ Konopliv, A. S.; Banerdt, W. B.; Sjogren, W. L. (May 1999). «Venus Gravity: 180th Degree and Order Model» (PDF). Icarus. 139 (1): 3–18. Bibcode:1999Icar..139….3K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.5176. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6086. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2010.

- ^ «Planets and Pluto: Physical Characteristics». NASA. 5 November 2008. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b «Planetary Facts». The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Margot, Jean-Luc; Campbell, Donald B.; Giorgini, Jon D.; et al. (29 April 2021). «Spin state and moment of inertia of Venus». Nature Astronomy. 5 (7): 676–683. arXiv:2103.01504. Bibcode:2021NatAs…5..676M. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01339-7. S2CID 232092194.

- ^ «Report on the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements of the planets and satellites». International Astronomical Union. 2000. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Mallama, Anthony; Krobusek, Bruce; Pavlov, Hristo (2017). «Comprehensive wide-band magnitudes and albedos for the planets, with applications to exo-planets and Planet Nine». Icarus. 282: 19–33. arXiv:1609.05048. Bibcode:2017Icar..282…19M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023. S2CID 119307693.

- ^ Haus, R.; et al. (July 2016). «Radiative energy balance of Venus based on improved models of the middle and lower atmosphere» (PDF). Icarus. 272: 178–205. Bibcode:2016Icar..272..178H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.048. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ «Atmospheres and Planetary Temperatures». American Chemical Society. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Mallama, Anthony; Hilton, James L. (October 2018). «Computing apparent planetary magnitudes for The Astronomical Almanac». Astronomy and Computing. 25: 10–24. arXiv:1808.01973. Bibcode:2018A&C….25…10M. doi:10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002. S2CID 69912809.

- ^ a b Herbst K, Banjac S, Atri D, Nordheim TA (1 January 2020). «Revisiting the cosmic-ray induced Venusian radiation dose in the context of habitability». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 633. Fig. 6. arXiv:1911.12788. Bibcode:2020A&A…633A..15H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936968. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 208513344.

- ^ Lawrence, Pete (2005). «In Search of the Venusian Shadow». Digitalsky.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Walker, John. «Viewing Venus in Broad Daylight». Fourmilab Switzerland. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ a b Hashimoto, George L.; Roos-Serote, Maarten; et al. (31 December 2008). «Felsic highland crust on Venus suggested by Galileo Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer data». Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. Advancing Earth and Space Science. 113 (E5). Bibcode:2008JGRE..113.0B24H. doi:10.1029/2008JE003134. S2CID 45474562.

- ^ Shiga, David (10 October 2007). «Did Venus’s ancient oceans incubate life?». New Scientist. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Jakosky, Bruce M. (1999). «Atmospheres of the Terrestrial Planets». In Beatty, J. Kelly; Petersen, Carolyn Collins; Chaikin, Andrew (eds.). The New Solar System (4th ed.). Boston: Sky Publishing. pp. 175–200. ISBN 978-0-933346-86-4. OCLC 39464951.

- ^ «Moons». NASA Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Castro, Joseph (3 February 2015). «What Would It Be Like to Live on Venus?». Space.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b «Venus: Facts & Figures». NASA. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. pp. 296–7. ISBN 978-0-19-509539-5. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ Lopes, Rosaly M. C.; Gregg, Tracy K. P. (2004). Volcanic worlds: exploring the Solar System’s volcanoes. Springer Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-540-00431-8.

- ^ Darling, David (n.d.). «Venus». Encyclopedia of Science. Dundee, Scotland. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Fredric W. (2014). «Venus: Atmosphere». In Tilman, Spohn; Breuer, Doris; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ «Venus». Case Western Reserve University. 13 September 2006. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Lewis, John S. (2004). Physics and Chemistry of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-12-446744-6.

- ^ Prockter, Louise (2005). «Ice in the Solar System» (PDF). Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest. 26 (2): 175–188. S2CID 17893191. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (11 December 2013). «Here’s Carl Sagan’s original essay on the dangers of climate change». Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ «The Planet Venus». Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Halliday, Alex N. (15 March 2013). «The origins of volatiles in the terrestrial planets». Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 105: 146–171. Bibcode:2013GeCoA.105..146H. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2012.11.015. ISSN 0016-7037. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Owen, Tobias; Bar-Nun, Akiva; Kleinfeld, Idit (July 1992). «Possible cometary origin of heavy noble gases in the atmospheres of Venus, Earth and Mars». Nature. 358 (6381): 43–46. Bibcode:1992Natur.358…43O. doi:10.1038/358043a0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11536499. S2CID 4357750. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Pepin, Robert O. (1 July 1991). «On the origin and early evolution of terrestrial planet atmospheres and meteoritic volatiles». Icarus. 92 (1): 2–79. Bibcode:1991Icar…92….2P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(91)90036-S. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Namiki, Noriyuki; Solomon, Sean C. (1998). «Volcanic degassing of argon and helium and the history of crustal production on Venus». Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 103 (E2): 3655–3677. Bibcode:1998JGR…103.3655N. doi:10.1029/97JE03032. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ O’Rourke, Joseph G.; Korenaga, Jun (1 November 2015). «Thermal evolution of Venus with argon degassing». Icarus. 260: 128–140. Bibcode:2015Icar..260..128O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.07.009. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Grinspoon, David H.; Bullock, M. A. (October 2007). «Searching for Evidence of Past Oceans on Venus». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 39: 540. Bibcode:2007DPS….39.6109G.

- ^ Kasting, J. F. (1988). «Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres and the evolution of Earth and Venus». Icarus. 74 (3): 472–494. Bibcode:1988Icar…74..472K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90116-9. PMID 11538226. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (13 November 2002). «Venusian Cloud Colonies». Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (July 2003). «Astrobiology: The Case for Venus» (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 56 (7–8): 250–254. Bibcode:2003JBIS…56..250L. NASA/TM—2003-212310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2011.

- ^ Cockell, Charles S. (December 1999). «Life on Venus». Planetary and Space Science. 47 (12): 1487–1501. Bibcode:1999P&SS…47.1487C. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(99)00036-7.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (14 September 2020). «Possible sign of life on Venus stirs up heated debate». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Greaves, J.S.; Richards, A.M.S.; Bains, W.; et al. (2020). «Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus». Nature Astronomy. 5 (7): 655–664. arXiv:2009.06593. Bibcode:2021NatAs…5..655G. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1174-4. S2CID 221655755. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Lincowski, Andrew P.; Meadows, Victoria S.; Crisp, David; Akins, Alex B.; Schwieterman, Edward W.; Arney, Giada N.; Wong, Michael L.; Steffes, Paul G.; Parenteau, M. Niki; Domagal-Goldman, Shawn (2021). «Claimed Detection of PH3 in the Clouds of Venus is Consistent with Mesospheric SO2» (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 908 (2): L44. arXiv:2101.09837. Bibcode:2021ApJ…908L..44L. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abde47. S2CID 231699227. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021.

- ^ Abigail Beall (21 October 2020). «More doubts cast on potential signs of life on Venus». New Scientist.

- ^ Ignas Snellan; et al. (December 2020). «Re-analysis of the 267 GHz ALMA observations of Venus». Astronomy & Astrophysics. 644: L2. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039717. S2CID 224803085.

- ^ Moshkin, B. E.; Ekonomov, A. P.; Golovin Iu. M. (1979). «Dust on the surface of Venus». Kosmicheskie Issledovaniia (Cosmic Research). 17 (2): 280–285. Bibcode:1979CosRe..17..232M.

- ^ a b Krasnopolsky, V. A.; Parshev, V. A. (1981). «Chemical composition of the atmosphere of Venus». Nature. 292 (5824): 610–613. Bibcode:1981Natur.292..610K. doi:10.1038/292610a0. S2CID 4369293.

- ^ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2006). «Chemical composition of Venus atmosphere and clouds: Some unsolved problems». Planetary and Space Science. 54 (13–14): 1352–1359. Bibcode:2006P&SS…54.1352K. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.04.019.

- ^ W. B. Rossow; A. D. del Genio; T. Eichler (1990). «Cloud-tracked winds from Pioneer Venus OCPP images». Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 47 (17): 2053–2084. Bibcode:1990JAtS…47.2053R. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<2053:CTWFVO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (7 May 2010). «Mission to probe Venus’s curious winds and test solar sail for propulsion». Science. 328 (5979): 677. Bibcode:2010Sci…328..677N. doi:10.1126/science.328.5979.677-a. PMID 20448159.

- ^ Lorenz, Ralph D.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Withers, Paul G.; McKay, Christopher P. (2001). «Titan, Mars and Earth: Entropy Production by Latitudinal Heat Transport» (PDF). Ames Research Center, University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ «Interplanetary Seasons». NASA Science. NASA. 19 June 2000. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Basilevsky A. T.; Head J. W. (2003). «The surface of Venus». Reports on Progress in Physics. 66 (10): 1699–1734. Bibcode:2003RPPh…66.1699B. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/66/10/R04. S2CID 13338382. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ McGill, G. E.; Stofan, E. R.; Smrekar, S. E. (2010). «Venus tectonics». In T. R. Watters; R. A. Schultz (eds.). Planetary Tectonics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–120. ISBN 978-0-521-76573-2. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Otten, Carolyn Jones (2004). ««Heavy metal» snow on Venus is lead sulfide». Washington University in St Louis. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ a b Lee, Yeon Joo; Jessup, Kandis-Lea; Perez-Hoyos, Santiago; Titov, Dmitrij V.; Lebonnois, Sebastien; Peralta, Javier; Horinouchi, Takeshi; Imamura, Takeshi; Limaye, Sanjay; Marcq, Emmanuel; Takagi, Masahiro; Yamazaki, Atsushi; Yamada, Manabu; Watanabe, Shigeto; Murakami, Shin-ya; Ogohara, Kazunori; McClintock, William M.; Holsclaw, Gregory; Roman, Anthony (26 August 2019). «Long-term Variations of Venus’s 365 nm Albedo Observed by Venus Express, Akatsuki, MESSENGER, and the Hubble Space Telescope». The Astronomical Journal. 158 (3): 126. arXiv:1907.09683. Bibcode:2019AJ….158..126L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab3120. S2CID 198179774. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ a b Lorenz, Ralph D. (20 June 2018). «Lightning detection on Venus: a critical review». Progress in Earth and Planetary Science. 5 (1): 34. Bibcode:2018PEPS….5…34L. doi:10.1186/s40645-018-0181-x. ISSN 2197-4284.

- ^ Kranopol’skii, V. A. (1980). «Lightning on Venus according to Information Obtained by the Satellites Venera 9 and 10«. Cosmic Research. 18 (3): 325–330. Bibcode:1980CosRe..18..325K.

- ^ a b Russell, C. T.; Phillips, J. L. (1990). «The Ashen Light». Advances in Space Research. 10 (5): 137–141. Bibcode:1990AdSpR..10e.137R. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(90)90174-X. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ «Venera 12 Descent Craft». National Space Science Data Center. NASA. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Russell, C. T.; Zhang, T. L.; Delva, M.; Magnes, W.; Strangeway, R. J.; Wei, H. Y. (November 2007). «Lightning on Venus inferred from whistler-mode waves in the ionosphere» (PDF). Nature. 450 (7170): 661–662. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..661R. doi:10.1038/nature05930. PMID 18046401. S2CID 4418778. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Hand, Eric (November 2007). «European mission reports from Venus». Nature (450): 633–660. doi:10.1038/news.2007.297. S2CID 129514118.

- ^ Staff (28 November 2007). «Venus offers Earth climate clues». BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ^ «ESA finds that Venus has an ozone layer too». European Space Agency. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ «When A Planet Behaves Like A Comet». European Space Agency. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (30 January 2013). «Venus Can Have ‘Comet-Like’ Atmosphere». Space.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Fukuhara, Tetsuya; Futaguchi, Masahiko; Hashimoto, George L.; et al. (16 January 2017). «Large stationary gravity wave in the atmosphere of Venus». Nature Geoscience. 10 (2): 85–88. Bibcode:2017NatGe..10…85F. doi:10.1038/ngeo2873.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (16 January 2017). «Venus wave may be Solar System’s biggest». BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (16 January 2017). «Venus Smiled, With a Mysterious Wave Across Its Atmosphere». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ «The HITRAN Database». Atomic and Molecular Physics Division, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

HITRAN is a compilation of spectroscopic parameters that a variety of computer codes use to predict and simulate the transmission and emission of light in the atmosphere.

- ^ «HITRAN on the Web Information System». V.E. Zuev Institute of Atmospheric Optics. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Mueller, Nils (2014). «Venus Surface and Interior». In Tilman, Spohn; Breuer, Doris; Johnson, T. V. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Solar System (3rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Esposito, Larry W. (9 March 1984). «Sulfur Dioxide: Episodic Injection Shows Evidence for Active Venus Volcanism». Science. 223 (4640): 1072–1074. Bibcode:1984Sci…223.1072E. doi:10.1126/science.223.4640.1072. PMID 17830154. S2CID 12832924. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Bullock, Mark A.; Grinspoon, David H. (March 2001). «The Recent Evolution of Climate on Venus» (PDF). Icarus. 150 (1): 19–37. Bibcode:2001Icar..150…19B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.6440. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6570. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2003.

- ^ Basilevsky, Alexander T.; Head, James W. III (1995). «Global stratigraphy of Venus: Analysis of a random sample of thirty-six test areas». Earth, Moon, and Planets. 66 (3): 285–336. Bibcode:1995EM&P…66..285B. doi:10.1007/BF00579467. S2CID 21736261.

- ^ Jones, Tom; Stofan, Ellen (2008). Planetology: Unlocking the Secrets of the Solar System. National Geographic Society. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4262-0121-9. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Kaufmann, W. J. (1994). Universe. New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7167-2379-0.

- ^ a b c d Nimmo, F.; McKenzie, D. (1998). «Volcanism and Tectonics on Venus». Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 26 (1): 23–53. Bibcode:1998AREPS..26…23N. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.23. S2CID 862354. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ a b Strom, Robert G.; Schaber, Gerald G.; Dawson, Douglas D. (25 May 1994). «The global resurfacing of Venus». Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (E5): 10899–10926. Bibcode:1994JGR….9910899S. doi:10.1029/94JE00388. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Frankel, Charles (1996). Volcanoes of the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47770-3.

- ^ Batson, R.M.; Russell J. F. (18–22 March 1991). «Naming the Newly Found Landforms on Venus» (PDF). Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference XXII. Houston, Texas. p. 65. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ a b Carolynn Young, ed. (1 August 1990). The Magellan Venus Explorer’s Guide. California: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. p. 93. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.