«SmartPhones» redirects here. For the song by Trey Songz, see SmartPhones (song).

A person using a smartphone

A smartphone is a portable computer device that combines mobile telephone and computing functions into one unit. They are distinguished from feature phones by their stronger hardware capabilities and extensive mobile operating systems, which facilitate wider software, internet (including web browsing over mobile broadband), and multimedia functionality (including music, video, cameras, and gaming), alongside core phone functions such as voice calls and text messaging. Smartphones typically contain a number of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chips, include various sensors that can be leveraged by pre-included and third-party software (such as a magnetometer, proximity sensors, barometer, gyroscope, accelerometer and more), and support wireless communications protocols (such as Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, or satellite navigation). More recently, smartphone manufacturers have begun to integrate satellite messaging connectivity and satellite emergency services into devices for use in remote regions, where there is no reliable cellular network.

Early smartphones were marketed primarily towards the enterprise market, attempting to bridge the functionality of standalone personal digital assistant (PDA) devices with support for cellular telephony, but were limited by their bulky form, short battery life, slow analog cellular networks, and the immaturity of wireless data services. These issues were eventually resolved with the exponential scaling and miniaturization of MOS transistors down to sub-micron levels (Moore’s law), the improved lithium-ion battery, faster digital mobile data networks (Edholm’s law), and more mature software platforms that allowed mobile device ecosystems to develop independently of data providers.

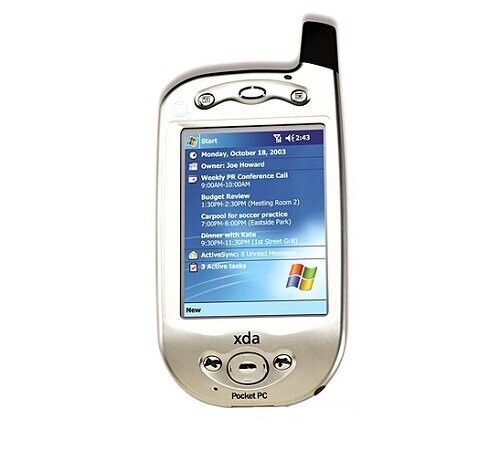

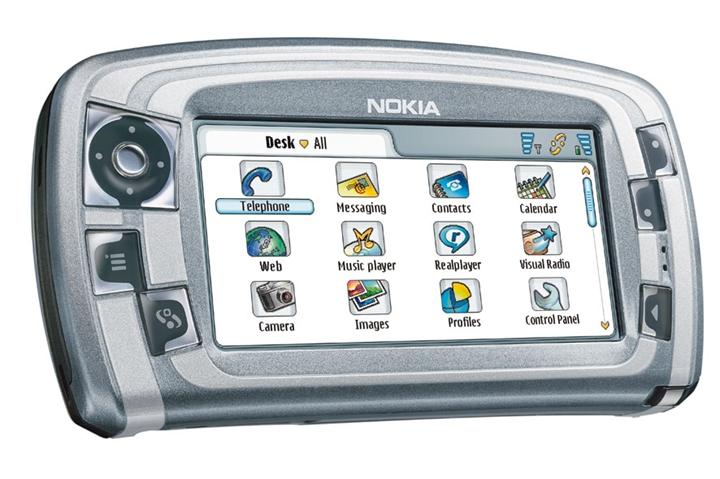

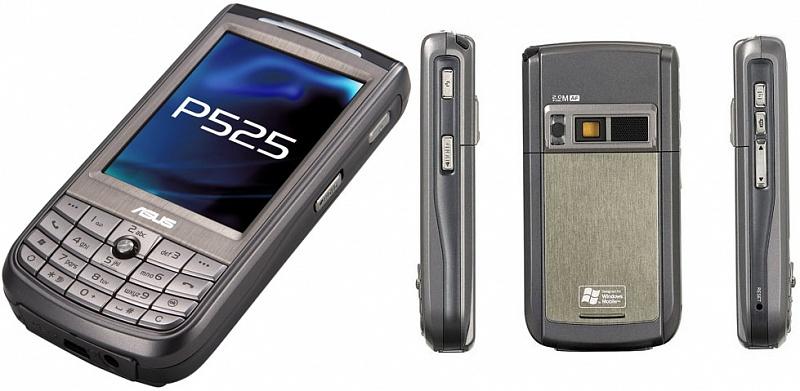

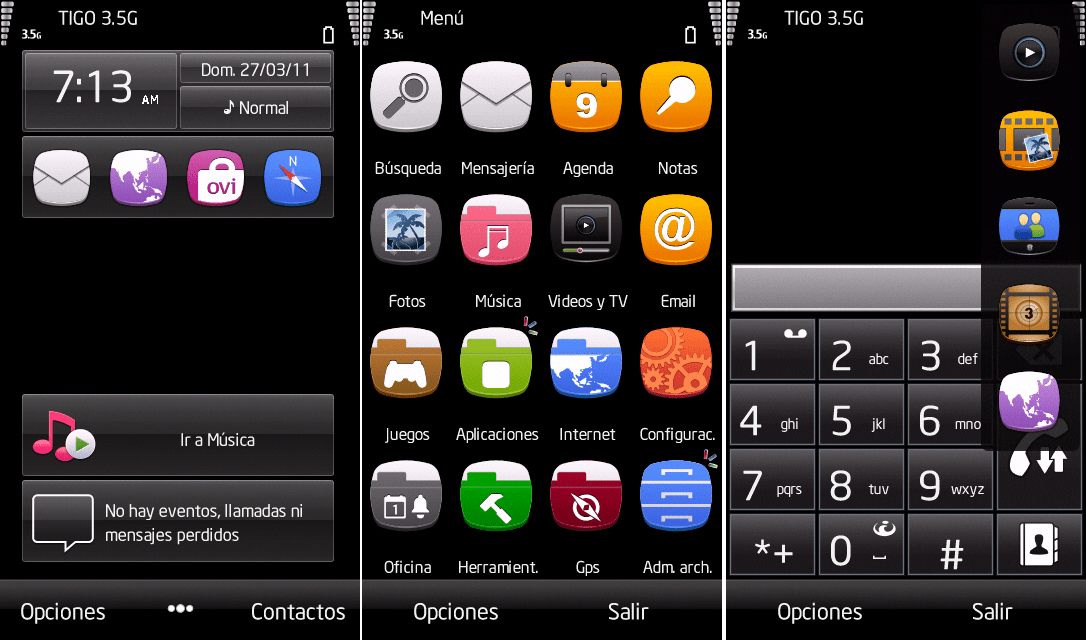

In the 2000s, NTT DoCoMo’s i-mode platform, BlackBerry, Nokia’s Symbian platform, and Windows Mobile began to gain market traction, with models often featuring QWERTY keyboards or resistive touchscreen input, and emphasizing access to push email and wireless internet. Following the rising popularity of the iPhone in the late 2000s, the majority of smartphones have featured thin, slate-like form factors, with large, capacitive screens with support for multi-touch gestures rather than physical keyboards, and offer the ability for users to download or purchase additional applications from a centralized store, and use cloud storage and synchronization, virtual assistants, as well as mobile payment services. Smartphones have largely replaced PDAs, handheld/palm-sized PCs, portable media players (PMP)[1] and to a lesser extent, handheld video game consoles.

Improved hardware and faster wireless communication (due to standards such as LTE) have bolstered the growth of the smartphone industry. In the third quarter of 2012, one billion smartphones were in use worldwide.[2] Global smartphone sales surpassed the sales figures for feature phones in early 2013.[3]

History

Forerunner

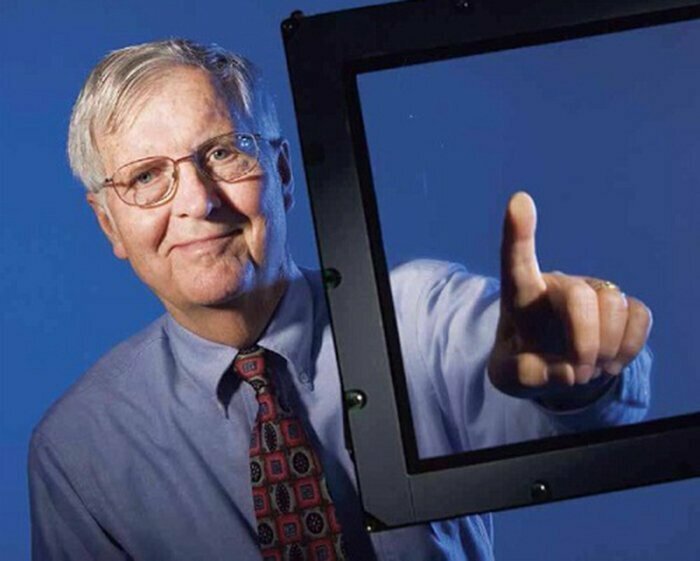

In the early 1990s, IBM engineer Frank Canova realised that chip-and-wireless technology was becoming small enough to use in handheld devices.[5] The first commercially available device that could be properly referred to as a «smartphone» began as a prototype called «Angler» developed by Canova in 1992 while at IBM and demonstrated in November of that year at the COMDEX computer industry trade show.[6][7][8] A refined version was marketed to consumers in 1994 by BellSouth under the name Simon Personal Communicator. In addition to placing and receiving cellular calls, the touchscreen-equipped Simon could send and receive faxes and emails. It included an address book, calendar, appointment scheduler, calculator, world time clock, and notepad, as well as other visionary mobile applications such as maps, stock reports and news.[9]

The IBM Simon was manufactured by Mitsubishi Electric, which integrated features from its own wireless personal digital assistant (PDA) and cellular radio technologies.[10] It featured a liquid-crystal display (LCD) and PC Card support.[11] The Simon was commercially unsuccessful, particularly due to its bulky form factor and limited battery life,[12] using NiCad batteries rather than the nickel–metal hydride batteries commonly used in mobile phones in the 1990s, or lithium-ion batteries used in modern smartphones.[13]

The term «smart phone» was not coined until a year after the introduction of the Simon, appearing in print as early as 1995, describing AT&T’s PhoneWriter Communicator.[14][non-primary source needed] The term «smartphone» was first used by Ericsson in 1997 to describe a new device concept, the GS88.[15]

PDA/phone hybrids

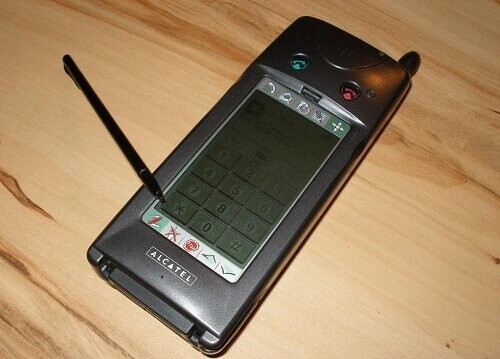

Beginning in the mid-late 1990s, many people who had mobile phones carried a separate dedicated PDA device, running early versions of operating systems such as Palm OS, Newton OS, Symbian or Windows CE/Pocket PC. These operating systems would later evolve into early mobile operating systems. Most of the «smartphones» in this era were hybrid devices that combined these existing familiar PDA OSes with basic phone hardware. The results were devices that were bulkier than either dedicated mobile phones or PDAs, but allowed a limited amount of cellular Internet access. PDA and mobile phone manufacturers competed in reducing the size of devices. The bulk of these smartphones combined with their high cost and expensive data plans, plus other drawbacks such as expansion limitations and decreased battery life compared to separate standalone devices, generally limited their popularity to «early adopters» and business users who needed portable connectivity.

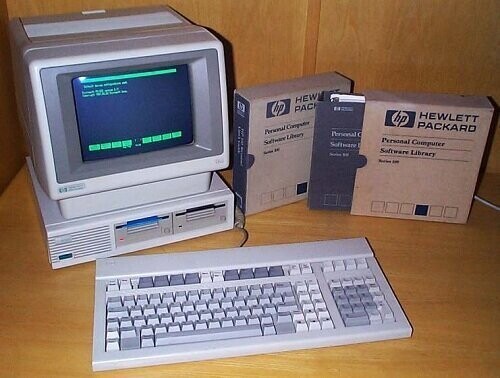

In March 1996, Hewlett-Packard released the OmniGo 700LX, a modified HP 200LX palmtop PC with a Nokia 2110 mobile phone piggybacked onto it and ROM-based software to support it. It had a 640×200 resolution CGA compatible four-shade gray-scale LCD screen and could be used to place and receive calls, and to create and receive text messages, emails and faxes. It was also 100% DOS 5.0 compatible, allowing it to run thousands of existing software titles, including early versions of Windows.

The Nokia 9110 Communicator, opened for access to keyboard

In August 1996, Nokia released the Nokia 9000 Communicator, a digital cellular PDA based on the Nokia 2110 with an integrated system based on the PEN/GEOS 3.0 operating system from Geoworks. The two components were attached by a hinge in what became known as a clamshell design, with the display above and a physical QWERTY keyboard below. The PDA provided e-mail; calendar, address book, calculator and notebook applications; text-based Web browsing; and could send and receive faxes. When closed, the device could be used as a digital cellular telephone.

In June 1999 Qualcomm released the «pdQ Smartphone», a CDMA digital PCS smartphone with an integrated Palm PDA and Internet connectivity.[16]

Subsequent landmark devices included:

- The Ericsson R380 (December 2000)[17] by Ericsson Mobile Communications,[18] the first phone running the operating system later named Symbian (it ran EPOC Release 5, which was renamed Symbian OS at Release 6). It had PDA functionality and limited Web browsing on a resistive touchscreen utilizing a stylus.[19] While it was marketed as a «smartphone»,[20] users could not install their own software on the device.

- The Kyocera 6035 (February 2001),[21] a dual-nature device with a separate Palm OS PDA operating system and CDMA mobile phone firmware. It supported limited Web browsing with the PDA software treating the phone hardware as an attached modem.[22][23]

- The Nokia 9210 Communicator (June 2001),[24] the first phone running Symbian (Release 6) with Nokia’s Series 80 platform (v1.0). This was the first Symbian phone platform allowing the installation of additional applications. Like the Nokia 9000 Communicator it’s a large clamshell device with a full physical QWERTY keyboard inside.

- Handspring’s Treo 180 (2002), the first smartphone that fully integrated the Palm OS on a GSM mobile phone having telephony, SMS messaging and Internet access built into the OS. The 180 model had a thumb-type keyboard and the 180g version had a Graffiti handwriting recognition area, instead.[25]

Japanese cell phones

In 1999, Japanese wireless provider NTT DoCoMo launched i-mode, a new mobile internet platform which provided data transmission speeds up to 9.6 kilobits per second, and access web services available through the platform such as online shopping. NTT DoCoMo’s i-mode used cHTML, a language which restricted some aspects of traditional HTML in favor of increasing data speed for the devices. Limited functionality, small screens and limited bandwidth allowed for phones to use the slower data speeds available. The rise of i-mode helped NTT DoCoMo accumulate an estimated 40 million subscribers by the end of 2001, and ranked first in market capitalization in Japan and second globally.[26] Japanese cell phones increasingly diverged from global standards and trends to offer other forms of advanced services and smartphone-like functionality that were specifically tailored to the Japanese market, such as mobile payments and shopping, near-field communication (NFC) allowing mobile wallet functionality to replace smart cards for transit fares, loyalty cards, identity cards, event tickets, coupons, money transfer, etc., downloadable content like musical ringtones, games, and comics, and 1seg mobile television.[27][28] Phones built by Japanese manufacturers used custom firmware, however, and didn’t yet feature standardized mobile operating systems designed to cater to third-party application development, so their software and ecosystems were akin to very advanced feature phones. As with other feature phones, additional software and services required partnerships and deals with providers.

The degree of integration between phones and carriers, unique phone features, non-standardized platforms, and tailoring to Japanese culture made it difficult for Japanese manufacturers to export their phones, especially when demand was so high in Japan that the companies didn’t feel the need to look elsewhere for additional profits.[29][30][31]

The rise of 3G technology in other markets and non-Japanese phones with powerful standardized smartphone operating systems, app stores, and advanced wireless network capabilities allowed non-Japanese phone manufacturers to finally break in to the Japanese market, gradually adopting Japanese phone features like emojis, mobile payments, NFC, etc. and spreading them to the rest of the world.

Early smartphones

Several BlackBerry smartphones, which were highly popular in the mid-late 2000s

Phones that made effective use of any significant data connectivity were still rare outside Japan until the introduction of the Danger Hiptop in 2002, which saw moderate success among U.S. consumers as the T-Mobile Sidekick. Later, in the mid-2000s, business users in the U.S. started to adopt devices based on Microsoft’s Windows Mobile, and then BlackBerry smartphones from Research In Motion. American users popularized the term «CrackBerry» in 2006 due to the BlackBerry’s addictive nature.[32] In the U.S., the high cost of data plans and relative rarity of devices with Wi-Fi capabilities that could avoid cellular data network usage kept adoption of smartphones mainly to business professionals and «early adopters.»

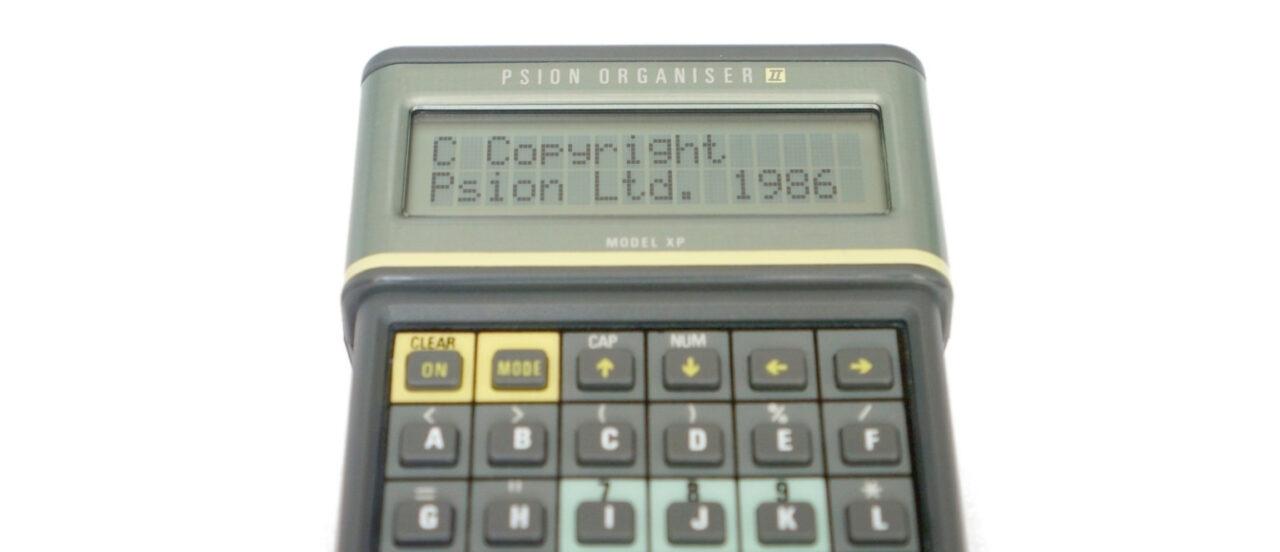

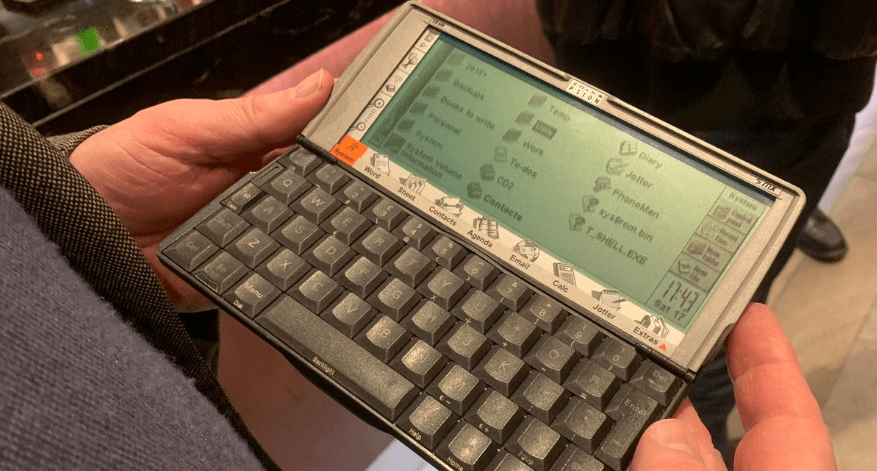

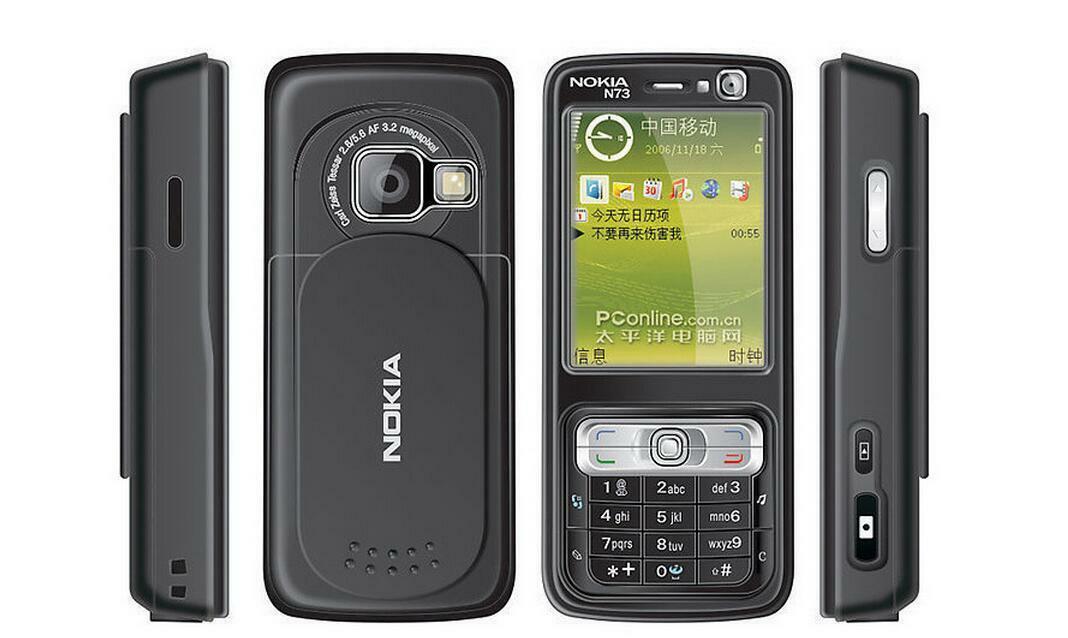

Outside the U.S. and Japan, Nokia was seeing success with its smartphones based on Symbian, originally developed by Psion for their personal organisers, and it was the most popular smartphone OS in Europe during the middle to late 2000s. Initially, Nokia’s Symbian smartphones were focused on business with the Eseries,[33] similar to Windows Mobile and BlackBerry devices at the time. From 2002 onwards, Nokia started producing consumer-focused smartphones, popularized by the entertainment-focused Nseries. Until 2010, Symbian was the world’s most widely used smartphone operating system.[34]

The touchscreen personal digital assistant (PDA)-derived nature of adapted operating systems like Palm OS, the «Pocket PC» versions of what was later Windows Mobile, and the UIQ interface that was originally designed for pen-based PDAs on Symbian OS devices resulted in some early smartphones having stylus-based interfaces. These allowed for virtual keyboards and/or handwriting input, thus also allowing easy entry of Asian characters.[35]

By the mid-2000s, the majority of smartphones had a physical QWERTY keyboard. Most used a «keyboard bar» form factor, like the BlackBerry line, Windows Mobile smartphones, Palm Treos, and some of the Nokia Eseries. A few hid their full physical QWERTY keyboard in a sliding form factor, like the Danger Hiptop line. Some even had only a numeric keypad using T9 text input, like the Nokia Nseries and other models in the Nokia Eseries. Resistive touchscreens with stylus-based interfaces could still be found on a few smartphones, like the Palm Treos, which had dropped their handwriting input after a few early models that were available in versions with Graffiti instead of a keyboard.

Form factor and operating system shifts

The LG Prada with a large capacitive touchscreen introduced in 2006

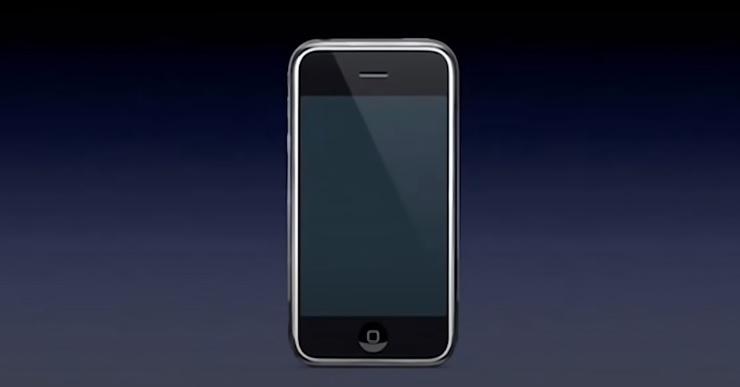

The original Apple iPhone; following its introduction the common smartphone form factor shifted to large touchscreen software interfaces without physical keypads[36]

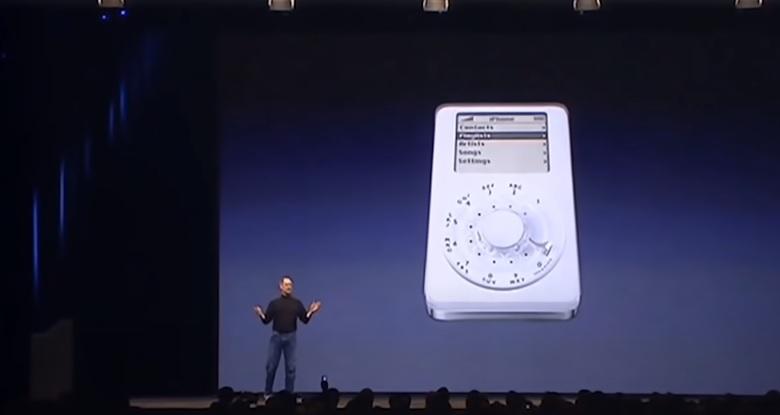

The late 2000s and early 2010s saw a shift in smartphone interfaces away from devices with physical keyboards and keypads to ones with large finger-operated capacitive touchscreens.[36] The first phone of any kind with a large capacitive touchscreen was the LG Prada, announced by LG in December 2006.[37] This was a fashionable feature phone created in collaboration with Italian luxury designer Prada with a 3″ 240×400 pixel screen, a 2-Megapixel digital camera with 144p video recording ability, an LED flash, and a miniature mirror for self portraits.[38][39]

In January 2007, Apple Computer introduced the iPhone.[40][41][42] It had a 3.5″ capacitive touchscreen with twice the common resolution of most smartphone screens at the time,[43] and introduced multi-touch to phones, which allowed gestures such as «pinching» to zoom in or out on photos, maps, and web pages. The iPhone was notable as being the first device of its kind targeted at the mass market to abandon the use of a stylus, keyboard, or keypad typical of contemporary smartphones, instead using a large touchscreen for direct finger input as its main means of interaction.[35]

The iPhone’s operating system was also a shift away from older operating systems (which older phones supported and which were adapted from PDAs and feature phones) to an operative system powerful enough to not require using a limited, stripped down web browser that can only render pages specially formatted using technologies such as WML, cHTML, or XHTML and instead ran a version of Apple’s Safari browser that could easily render full websites[44][45][46] not specifically designed for phones.[47]

Later Apple shipped a software update that gave the iPhone a built-in on-device App Store allowing direct wireless downloads of third-party software.[48][49] This kind of centralized App Store and free developer tools[50][51] quickly became the new main paradigm for all smartphone platforms for software development, distribution, discovery, installation, and payment, in place of expensive developer tools that required official approval to use and a dependence on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms.[36]

The advantages of a design with software powerful enough to support advanced applications and a large capacitive touchscreen affected the development of another smartphone OS platform, Android, with a more BlackBerry-like prototype device scrapped in favor of a touchscreen device with a slide-out physical keyboard, as Google’s engineers thought at the time that a touchscreen could not completely replace a physical keyboard and buttons.[52][53][54] Android is based around a modified Linux kernel, again providing more power than mobile operating systems adapted from PDAs and feature phones. The first Android device, the horizontal-sliding HTC Dream, was released in September 2008.[55]

In 2012, Asus started experimenting with a convertible docking system named PadFone, where the standalone handset can when necessary be inserted into a tablet-sized screen unit with integrated supportive battery and used as such.

In 2013 and 2014, Samsung experimented with the hybrid combination of compact camera and smartphone, releasing the Galaxy S4 Zoom and K Zoom, each equipped with integrated 10× optical zoom lens and manual parameter settings (including manual exposure and focus) years before these were widely adapted among smartphones. The S4 Zoom additionally has a rotary knob ring around the lens and a tripod mount.

While screen sizes have increased, manufacturers have attempted to make smartphones thinner at the expense of utility and sturdiness, since a thinner frame is more vulnerable to bending and has less space for components, namely battery capacity.[56][57]

Operating system competition

The iPhone and later touchscreen-only Android devices together popularized the slate form factor, based on a large capacitive touchscreen as the sole means of interaction, and led to the decline of earlier, keyboard- and keypad-focused platforms.[36] Later, navigation keys such as the home, back, menu, task and search buttons have also been increasingly replaced by nonphysical touch keys, then virtual, simulated on-screen navigation keys, commonly with access combinations such as a long press of the task key to simulate a short menu key press, as with home button to search.[58] More recent «bezel-less» types have their screen surface space extended to the unit’s front bottom to compensate for the display area lost for simulating the navigation keys. While virtual keys offer more potential customizability, their location may be inconsistent among systems and/or depending on screen rotation and software used.

Multiple vendors attempted to update or replace their existing smartphone platforms and devices to better-compete with Android and the iPhone; Palm unveiled a new platform known as webOS for its Palm Pre in late-2009 to replace Palm OS, which featured a focus on a task-based «card» metaphor and seamless synchronization and integration between various online services (as opposed to the then-conventional concept of a smartphone needing a PC to serve as a «canonical, authoritative repository» for user data).[59][60] HP acquired Palm in 2010 and released several other webOS devices, including the Pre 3 and HP TouchPad tablet. As part of a proposed divestment of its consumer business to focus on enterprise software, HP abruptly ended development of future webOS devices in August 2011, and sold the rights to webOS to LG Electronics in 2013, for use as a smart TV platform.[61][62]

Research in Motion introduced the vertical-sliding BlackBerry Torch and BlackBerry OS 6 in 2010, which featured a redesigned user interface, support for gestures such as pinch-to-zoom, and a new web browser based on the same WebKit rendering engine used by the iPhone.[63][64] The following year, RIM released BlackBerry OS 7 and new models in the Bold and Torch ranges, which included a new Bold with a touchscreen alongside its keyboard, and the Torch 9860—the first BlackBerry phone to not include a physical keyboard.[65] In 2013, it replaced the legacy BlackBerry OS with a revamped, QNX-based platform known as BlackBerry 10, with the all-touch BlackBerry Z10 and keyboard-equipped Q10 as launch devices.[66]

In 2010, Microsoft unveiled a replacement for Windows Mobile known as Windows Phone, featuring a new touchscreen-centric user interface built around flat design and typography, a home screen with «live tiles» containing feeds of updates from apps, as well as integrated Microsoft Office apps.[67] In February 2011, Nokia announced that it had entered into a major partnership with Microsoft, under which it would exclusively use Windows Phone on all of its future smartphones, and integrate Microsoft’s Bing search engine and Bing Maps (which, as part of the partnership, would also license Nokia Maps data) into all future devices. The announcement led to the abandonment of both Symbian, as well as MeeGo—a Linux-based mobile platform it was co-developing with Intel.[68][69][70] Nokia’s low-end Lumia 520 saw strong demand and helped Windows Phone gain niche popularity in some markets,[71] overtaking BlackBerry in global market share in 2013.[72][73]

In mid-June 2012, Meizu released its mobile operating system, Flyme OS.

Many of these attempts to compete with Android and iPhone were short-lived. Over the course of the decade, the two platforms became a clear duopoly in smartphone sales and market share, with BlackBerry, Windows Phone, and other operating systems eventually stagnating to little or no measurable market share.[74][75] In 2015, BlackBerry began to pivot away from its in-house mobile platforms in favor of producing Android devices, focusing on a security-enhanced distribution of the software. The following year, the company announced that it would also exit the hardware market to focus more on software and its enterprise middleware,[76] and began to license the BlackBerry brand and its Android distribution to third-party OEMs such as TCL for future devices.[77][78]

In September 2013, Microsoft announced its intent to acquire Nokia’s mobile device business for $7.1 billion, as part of a strategy under CEO Steve Ballmer for Microsoft to be a «devices and services» company.[79] Despite the growth of Windows Phone and the Lumia range (which accounted for nearly 90% of all Windows Phone devices sold),[80] the platform never had significant market share in the key U.S. market,[71] and Microsoft was unable to maintain Windows Phone’s momentum in the years that followed, resulting in dwindling interest from users and app developers.[81] After Balmer was succeeded by Satya Nadella (who has placed a larger focus on software and cloud computing) as CEO of Microsoft, it took a $7.6 billion write-off on the Nokia assets in July 2015, and laid off nearly the entire Microsoft Mobile unit in May 2016.[82][83][79]

Prior to the completion of the sale to Microsoft, Nokia released a series of Android-derived smartphones for emerging markets known as Nokia X, which combined an Android-based platform with elements of Windows Phone and Nokia’s feature phone platform Asha, using Microsoft and Nokia services rather than Google.[84]

Camera advancements

The Nokia 9 PureView features a five-lens camera array with Zeiss optics, using a mixture of color and monochrome sensors.[85]

The first commercial camera phone was the Kyocera Visual Phone VP-210, released in Japan in May 1999.[86] It was called a «mobile videophone» at the time,[87] and had a 110,000-pixel front-facing camera.[86] It could send up to two images per second over Japan’s Personal Handy-phone System (PHS) cellular network, and store up to 20 JPEG digital images, which could be sent over e-mail.[86] The first mass-market camera phone was the J-SH04, a Sharp J-Phone model sold in Japan in November 2000.[88][89] It could instantly transmit pictures via cell phone telecommunication.[90]

By the mid-2000s, higher-end cell phones commonly had integrated digital cameras. In 2003 camera phones outsold stand-alone digital cameras, and in 2006 they outsold film and digital stand-alone cameras. Five billion camera phones were sold in five years, and by 2007 more than half of the installed base of all mobile phones were camera phones. Sales of separate cameras peaked in 2008.[91]

Many early smartphones didn’t have cameras at all, and earlier models that had them had low performance and insufficient image and video quality that could not compete with budget pocket cameras and fulfill user’s needs.[92] By the beginning of the 2010s almost all smartphones had an integrated digital camera. The decline in sales of stand-alone cameras accelerated due to the increasing use of smartphones with rapidly improving camera technology for casual photography, easier image manipulation, and abilities to directly share photos through the use of apps and web-based services.[93][94][95][96] By 2011, cell phones with integrated cameras were selling hundreds of millions per year. In 2015, digital camera sales were 35.395 million units or only less than a third of digital camera sales numbers at their peak and also slightly less than film camera sold number at their peak.[97][98]

Contributing to the rise in popularity of smartphones being used over dedicated cameras for photography, smaller pocket cameras have difficulty producing bokeh in images, but nowadays, some smartphones have dual-lens cameras that reproduce the bokeh effect easily, and can even rearrange the level of bokeh after shooting. This works by capturing multiple images with different focus settings, then combining the background of the main image with a macro focus shot.

In 2007 the Nokia N95 was notable as a smartphone that had a 5.0 Megapixel (MP) camera, when most others had cameras with around 3 MP or less than 2 MP. Some specialized feature phones like the LG Viewty, Samsung SGH-G800, and Sony Ericsson K850i, all released later that year, also had 5.0 MP cameras. By 2010 5.0 MP cameras were common; a few smartphones had 8.0 MP cameras and the Nokia N8, Sony Ericsson Satio,[99] and Samsung M8910 Pixon12[100] feature phone had 12 MP. The main camera of the 2009 Nokia N86 uniquely features a three-level aperture lens.[101]

The Altek Leo, a 14-megapixel smartphone with 3x optical zoom lens and 720p HD video camera was released in late 2010.[102]

In 2011, the same year the Nintendo 3DS was released, HTC unveiled the Evo 3D, a 3D phone with a dual five-megapixel rear camera setup for spatial imaging, among the earliest mobile phones with more than one rear camera.

The 2012 Samsung Galaxy S3 introduced the ability to capture photos using voice commands.[103]

In 2012 Nokia announced and released the Nokia 808 PureView, featuring a 41-megapixel 1/1.2-inch sensor and a high-resolution f/2.4 Zeiss all-aspherical one-group lens. The high resolution enables four times of lossless digital zoom at 1080p and six times at 720p resolution, using image sensor cropping.[104] The 2013 Nokia Lumia 1020 has a similar high-resolution camera setup, with the addition of optical image stabilization and manual camera settings years before common among high-end mobile phones, although lacking expandable storage that could be of use for accordingly high file sizes.

Mobile optical image stabilization was first introduced by Nokia in 2012 with the Lumia 920, enabling prolonged exposure times for low-light photography and smoothing out handheld video shake whose appearance would magnify over a larger display such as a monitor or television set, which would be detrimental to watching experience.

Since 2012, smartphones have become increasingly able to capture photos while filming. The resolution of those photos resolution may vary between devices. Samsung has used the highest image sensor resolution at the video’s aspect ratio, which at 16:9 is 6 Megapixels (3264×1836) on the Galaxy S3 and 9.6 Megapixels (4128×2322) on the Galaxy S4.[105][106] The earliest iPhones with such functionality, iPhone 5 and 5s, captured simultaneous photos at 0.9 Megapixels (1280×720) while filming.[107]

Starting in 2013 on the Xperia Z1, Sony experimented with real-time augmented reality camera effects such as floating text, virtual plants, volcano, and a dinosaur walking in the scenery.[108] Apple later did similarly in 2017 with the iPhone X.[109]

In the same year, iOS 7 introduced the later widely implemented viewfinder intuition, where exposure value can be adjusted through vertical swiping, after focus and exposure has been set by tapping, and even while locked after holding down for a brief moment.[110] On some devices, this intuition may be restricted by software in video/slow motion modes and for front camera.

In 2013, Samsung unveiled the Galaxy S4 Zoom smartphone with the grip shape of a compact camera and a 10× optical zoom lens, as well as a rotary knob ring around the lens, as used on higher-end compact cameras, and an ISO 1222 tripod mount. It is equipped with manual parameter settings, including for focus and exposure. The successor 2014 Samsung Galaxy K Zoom brought resolution and performance enhancements, but lacks the rotary knob and tripod mount to allow for a more smartphone-like shape with less protruding lens.[111]

The 2014 Panasonic Lumix DMC-CM1 was another attempt at mixing mobile phone with compact camera, so much so that it inherited the Lumix brand. While lacking optical zoom, its image sensor has a format of 1″, as used in high-end compact cameras such as the Lumix DMC-LX100 and Sony CyberShot DSC-RX100 series, with multiple times the surface size of a typical mobile camera image sensor, as well as support for light sensitivities of up to ISO 25600, well beyond the typical mobile camera light sensitivity range. As of 2021, no successor has been released.[112][113]

In 2013 and 2014, HTC experimentally traded in pixel count for pixel surface size on their One M7 and M8, both with only four megapixels, marketed as UltraPixel, citing improved brightness and less noise in low light, though the more recent One M8 lacks optical image stabilization.[114]

The One M8 additionally was one of the earliest smartphones to be equipped with a dual camera setup. Its software allows generating visual spacial effects such as 3D panning, weather effects, and focus adjustment («UFocus»), simulating the postphotographic selective focussing capability of images produced by a light-field camera.[115] HTC returned to a high-megapixel single-camera setup on the 2015 One M9.

Meanwhile, in 2014, LG Mobile started experimenting with time-of-flight camera functionality, where a rear laser beam that measures distance accelerates autofocus.

Phase-detection autofocus was increasingly adapted throughout the mid-2010s, allowing for quicker and more accurate focussing than contrast detection.

In 2016 Apple introduced the iPhone 7 Plus, one of the phones to popularize a dual camera setup. The iPhone 7 Plus included a main 12 MP camera along with a 12 MP telephoto camera.[116] In early 2018 Huawei released a new flagship phone, the Huawei P20 Pro, one of the first triple camera lens setups with Leica optics.[117] In late 2018, Samsung released a new mid-range smartphone, the Galaxy A9 (2018) with the world’s first quad camera setup. The Nokia 9 PureView was released in 2019 featuring a penta-lens camera system.[118]

2019 saw the commercialization of high resolution sensors, which use pixel binning to capture more light. 48 MP and 64 MP sensors developed by Sony and Samsung are commonly used by several manufacturers. 108 MP sensors were first implemented in late 2019 and early 2020.

Video resolution

| Resolution | First year |

|---|---|

| 720p (HD) | 2009 |

| 720p at 60fps | 2012 |

| 1080p (Full HD) | 2011 |

| 1080p at 60fps | 2013 |

| 2160p (4K) | 2013 |

| 2160p at 60fps | 2017 |

| 4320p (8K) | 2020 |

With stronger getting chipsets to handle computing workload demands at higher pixel rates, mobile video resolution and framerate has caught up with dedicated consumer-grade cameras over years.

In 2009 the Samsung Omnia HD became the first mobile phone with 720p HD video recording. In the same year, Apple brought video recording initially to the iPhone 3GS, at 480p, whereas the 2007 original iPhone and 2008 iPhone 3G lacked video recording entirely.

720p was more widely adapted in 2010, on smartphones such as the original Samsung Galaxy S, Sony Ericsson Xperia X10, iPhone 4, and HTC Desire HD.

The early 2010s brought a steep increase in mobile video resolution. 1080p mobile video recording was achieved in 2011 on the Samsung Galaxy S2, HTC Sensation, and iPhone 4s.

In 2012 and 2013, select devices with 720p filming at 60 frames per second were released: the Asus PadFone 2 and HTC One M7, unlike flagships of Samsung, Sony, and Apple. However, the 2013 Samsung Galaxy S4 Zoom does support it.

In 2013, the Samsung Galaxy Note 3 introduced 2160p (4K) video recording at 30 frames per second, as well as 1080p doubled to 60 frames per second for smoothness.

Other vendors adapted 2160p recording in 2014, including the optically stabilized LG G3. Apple first implemented it in late 2015 on the iPhone 6s and 6s Plus.

The framerate at 2160p was widely doubled to 60 in 2017 and 2018, starting with the iPhone 8, Galaxy S9, LG G7, and OnePlus 6.

Sufficient computing performance of chipsets and image sensor resolution and its reading speeds have enabled mobile 4320p (8K) filming in 2020, introduced with the Samsung Galaxy S20 and Redmi K30 Pro, though some upper resolution levels were foregone (skipped) throughout development, including 1440p (2.5K), 2880p (5K), and 3240p (6K), except 1440p on Samsung Galaxy front cameras.

- Mid-class

Among mid-range smartphone series, the introduction of higher video resolutions was initially delayed by two to three years compared to flagship counterparts. 720p was widely adapted in 2012, including with the Samsung Galaxy S3 Mini, Sony Xperia go, and 1080p in 2013 on the Samsung Galaxy S4 Mini and HTC One mini.

The proliferation of video resolutions beyond 1080p has been postponed by several years. The mid-class Sony Xperia M5 supported 2160p filming in 2016, whereas Samsung’s mid-class series such as the Galaxy J and A series were strictly limited to 1080p in resolution and 30 frames per second at any resolution for six years until around 2019, whether and how much for technical reasons is unclear.

- Setting

A lower video resolution setting may be desirable to extend recording time by reducing space storage and power consumption.

The camera software of some sophisticated devices such as the LG V10 is equipped with separate controls for resolution, frame rate, and bit rate, within a technically supported range of pixel rate.[119]

Slow motion video

A distinction between different camera software is the method used to store high frame rate video footage, with more recent phones[a] retaining both the image sensor’s original output frame rate and audio, while earlier phones do not record audio and stretch the video so it can be played back slowly at default speed.

While the stretched encoding method used on earlier phones enables slow motion playback on video player software that lacks manual playback speed control, typically found on older devices, if the aim were to achieve a slow motion effect, the real-time method used by more recent phones offers greater versatility for video editing, where slowed down portions of the footage can be freely selected by the user, and exported into a separate video. A rudimentary video editing software for this purpose is usually pre-installed. The video can optionally be played back at normal (real-time) speed, acting as usual video.

- Development

The earliest smartphone known to feature a slow motion mode is the 2009 Samsung i8000 Omnia II, which can record at QVGA (320×240) at 120 fps (frames per second). Slow motion was not available on the 2010 Galaxy S1, 2011 Galaxy S2, 2011 Galaxy Note 1, and 2012 Galaxy S3 flagships.

In early 2012, the HTC One X allowed 768×432 pixel slow motion filming at an undocumented frame rate. The output footage has been measured as a third of real-time speed.[120]

In late 2012, the Galaxy Note 2 brought back slow motion, with D1 (720×480) at 120 fps. In early 2013, the Galaxy S4 and HTC One M7 recorded at that frame rate with 800×450, followed by the Note 3 and iPhone 5s with 720p (1280×720) in late 2013, the latter of which retaines audio and original sensor frame rate, as with all later iPhones. In early 2014, the Sony Xperia Z2 and HTC One M8 adapted this resolution as well. In late 2014, the iPhone 6 doubled the frame rate to 240fps, and in late 2015, the iPhone 6s added support for 1080p (1920×1080) at 120 frames per second. In early 2015, the Galaxy S6 became the first Samsung mobile phone to retain the sensor framerate and audio, and in early 2016, the Galaxy S7 became the first Samsung mobile phone with 240fps recording, also at 720p.

In early 2015, the MT6795 chipset by MediaTek promised 1080p@480fps video recording. The project’s status remains indefinite.[121]

Since early 2017, starting with the Sony Xperia XZ, smartphones have been released with a slow motion mode that unsustainably records at framerates multiple times as high, by temporarily storing frames on the image sensor’s internal burst memory. Such a recording endures few real-time seconds at most.

In late 2017, the iPhone 8 brought 1080p at 240fps, as well as 2160p at 60fps, followed by the Galaxy S9 in early 2018. In mid-2018, the OnePlus 6 brought 720p at 480fps, sustainable for one minute.

In early 2021, the OnePlus 9 Pro became the first phone with 2160p at 120fps.

HDR video

The first smartphones to record HDR video were the early 2013 Sony Xperia Z and mid-2013 Xperia Z Ultra, followed by the early 2014 Galaxy S5, all at 1080p.

Audio recording

Mobile phones with multiple microphones usually allow video recording with stereo audio for spaciality, with Samsung, Sony, and HTC initially implementing it in 2012 on their Samsung Galaxy S3, Sony Xperia S, and HTC One X.[122][123][124] Apple implemented stereo audio starting with the 2018 iPhone Xs family and iPhone XR.[125]

Front cameras

Photo

Emphasis is being put on the front camera since the mid-2010s, where front cameras have reached resolutions as high as typical rear cameras, such as the 2015 LG G4 (8 megapixels), Sony Xperia C5 Ultra (13 megapixels), and 2016 Sony Xperia XA Ultra (16 megapixels, optically stabilized). The 2015 LG V10 brought a dual front camera system where the second has a wider angle for group photography. Samsung implemented a front-camera sweep panorama (panorama selfie) feature since the Galaxy Note 4 to extend the field of view.

Video

In 2012, the Galaxy S3 and iPhone 5 brought 720p HD front video recording (at 30 fps). In early 2013, the Samsung Galaxy S4, HTC One M7 and Sony Xperia Z brought 1080p Full HD at that framerate, and in late 2014, the Galaxy Note 4 introduced 1440p video recording on the front camera. Apple adapted 1080p front camera video with the late 2016 iPhone 7.

In 2019, smartphones started adapting 2160p 4K video recording on the front camera, six years after rear camera 2160p commenced with the Galaxy Note 3.

Display advancements

A Moto G7 Power; its display uses a tall aspect ratio and includes a «notch».

In the early 2010s, larger smartphones with screen sizes of at least 140 millimetres (5.5 in) diagonal, dubbed «phablets», began to achieve popularity, with the 2011 Samsung Galaxy Note series gaining notably wide adoption.[126][127] In 2013, Huawei launched the Huawei Mate series, sporting a 155 millimetres (6.1 in) HD (1280×720) IPS+ LCD display, which was considered to be quite large at the time.[128]

Some companies began to release smartphones in 2013 incorporating flexible displays to create curved form factors, such as the Samsung Galaxy Round and LG G Flex.[129][130][131]

By 2014, 1440p displays began to appear on high-end smartphones.[132] In 2015, Sony released the Xperia Z5 Premium, featuring a 4K resolution display, although only images and videos could actually be rendered at that resolution (all other software was shown at 1080p).[133]

New trends for smartphone displays began to emerge in 2017, with both LG and Samsung releasing flagship smartphones (LG G6 and Galaxy S8), utilizing displays with taller aspect ratios than the common 16:9 ratio, and a high screen-to-body ratio, also known as a «bezel-less design». These designs allow the display to have a larger diagonal measurement, but with a slimmer width than 16:9 displays with an equivalent screen size.[134][135][136]

Another trend popularized in 2017 were displays containing tab-like cut-outs at the top-centre—colloquially known as a «notch»—to contain the front-facing camera, and sometimes other sensors typically located along the top bezel of a device.[137][138] These designs allow for «edge-to-edge» displays that take up nearly the entire height of the device, with little to no bezel along the top, and sometimes a minimal bottom bezel as well. This design characteristic appeared almost simultaneously on the Sharp Aquos S2 and the Essential Phone,[139] which featured small circular tabs for their cameras, followed just a month later by the iPhone X, which used a wider tab to contain a camera and facial scanning system known as Face ID.[140] The 2016 LG V10 had a precursor to the concept, with a portion of the screen wrapped around the camera area in the top-left corner, and the resulting area marketed as a «second» display that could be used for various supplemental features.[141]

Other variations of the practice later emerged, such as a «hole-punch» camera (such as those of the Honor View 20, and Samsung’s Galaxy A8s and Galaxy S10)—eschewing the tabbed «notch» for a circular or rounded-rectangular cut-out within the screen instead,[142] while Oppo released the first «all-screen» phones with no notches at all,[143] including one with a mechanical front camera that pops up from the top of the device (Find X),[144] and a 2019 prototype for a front-facing camera that can be embedded and hidden below the display, using a special partially-translucent screen structure that allows light to reach the image sensor below the panel.[145] The first implementation was the ZTE Axon 20 5G, with a 32 MP sensor manufactured by Visionox.[146]

Displays supporting refresh rates higher than 60 Hz (such as 90 Hz or 120 Hz) also began to appear on smartphones in 2017; initially confined to «gaming» smartphones such as the Razer Phone (2017) and Asus ROG Phone (2018), they later became more common on flagship phones such as the Pixel 4 (2019) and Samsung Galaxy S21 series (2021). Higher refresh rates allow for smoother motion and lower input latency, but often at the cost of battery life. As such, the device may offer a means to disable high refresh rates, or be configured to automatically reduce the refresh rate when there is low on-screen motion.[147][148]

Multi-tasking

An early implementation of multiple simultaneous tasks on a smartphone display are the picture-in-picture video playback mode («pop-up play») and «live video list» with playing video thumbnails of the 2012 Samsung Galaxy S3, the former of which was later delivered to the 2011 Samsung Galaxy Note through a software update.[149][150] Later that year, a split-screen mode was implemented on the Galaxy Note 2, later retrofitted on the Galaxy S3 through the «premium suite upgrade».[151]

The earliest implementation of desktop and laptop-like windowing was on the 2013 Samsung Galaxy Note 3.[152]

Foldable smartphones

Smartphones utilizing flexible displays were theorized as possible once manufacturing costs and production processes were feasible.[153] In November 2018, the startup company Royole unveiled the first commercially available foldable smartphone, the Royole FlexPai. Also that month, Samsung presented a prototype phone featuring an «Infinity Flex Display» at its developers conference, with a smaller, outer display on its «cover», and a larger, tablet-sized display when opened. Samsung stated that it also had to develop a new polymer material to coat the display as opposed to glass.[154][155][156] Samsung officially announced the Galaxy Fold, based on the previously demonstrated prototype, in February 2019 for an originally-scheduled release in late-April.[157] Due to various durability issues with the display and hinge systems encountered by early reviewers, the release of the Galaxy Fold was delayed to September to allow for design changes.[158]

In November 2019, Motorola unveiled a variation of the concept with its re-imagining of the Razr, using a horizontally-folding display to create a clamshell form factor inspired by its previous feature phone range of the same name.[159] Samsung would unveil a similar device known as the Galaxy Z Flip the following February.[160]

Other developments in the 2010s

The first smartphone with a fingerprint reader was the Motorola Atrix 4G in 2011.[161] In September 2013, the iPhone 5S was unveiled as the first smartphone on a major U.S. carrier since the Atrix to feature this technology.[162] Once again, the iPhone popularized this concept. One of the barriers of fingerprint reading amongst consumers was security concerns, however Apple was able to address these concerns by encrypting this fingerprint data onto the A7 Processor located inside the phone as well as make sure this information could not be accessed by third-party applications and is not stored in iCloud or Apple servers[163]

In 2012, Samsung introduced the Galaxy S3 (GT-i9300) with retrofittable wireless charging, pop-up video playback, 4G-LTE variant (GT-i9305) quad-core processor.

In 2013, Fairphone launched its first «socially ethical» smartphone at the London Design Festival to address concerns regarding the sourcing of materials in the manufacturing[164] followed by Shiftphone in 2015.[165] In late 2013, QSAlpha commenced production of a smartphone designed entirely around security, encryption and identity protection.[166]

In October 2013, Motorola Mobility announced Project Ara, a concept for a modular smartphone platform that would allow users to customize and upgrade their phones with add-on modules that attached magnetically to a frame.[167][168] Ara was retained by Google following its sale of Motorola Mobility to Lenovo,[169] but was shelved in 2016.[170] That year, LG and Motorola both unveiled smartphones featuring a limited form of modularity for accessories; the LG G5 allowed accessories to be installed via the removal of its battery compartment,[171] while the Moto Z utilizes accessories attached magnetically to the rear of the device.[172]

Microsoft, expanding upon the concept of Motorola’s short-lived «Webtop», unveiled functionality for its Windows 10 operating system for phones that allows supported devices to be docked for use with a PC-styled desktop environment.[173][174]

Samsung and LG used to be the «last standing» manufacturers to offer flagship devices with user-replaceable batteries.

But in 2015, Samsung succumbed to the minimalism trend set by Apple, introducing the Galaxy S6 without a user-replaceable battery.

In addition, Samsung was criticised for pruning long-standing features such as MHL, MicroUSB 3.0, water resistance and MicroSD card support, of which the latter two came back in 2016 with the Galaxy S7 and S7 Edge.

As of 2015, the global median for smartphone ownership was 43%.[175] Statista forecast that 2.87 billion people would own smartphones in 2020.[176]

Major technologies that began to trend in 2016 included a focus on virtual reality and augmented reality experiences catered towards smartphones, the newly introduced USB-C connector, and improving LTE technologies.[177]

In 2016, adjustable screen resolution known from desktop operating systems was introduced to smartphones for power saving, whereas variable screen refresh rates were popularized in 2020.[178][179]

In 2018, the first smartphones featuring fingerprint readers embedded within OLED displays were announced, followed in 2019 by an implementation using an ultrasonic sensor on the Samsung Galaxy S10.[180][181]

In 2019, the majority of smartphones released have more than one camera, are waterproof with IP67 and IP68 ratings, and unlock using facial recognition or fingerprint scanners.[182]

This layout of the camera viewfinder was first introduced by Apple with iOS 7 in 2013. Towards the late 2010s, several other smartphone vendors have ditched their layout and implemented variations of this layout.

Designs first implemented by Apple have been replicated by other vendors several times. These include a sealed body that does not allow replacing the battery, a lack of the physical audio connecter (since the iPhone 7 from 2016), a screen with a cut-out area at the top for the earphone and front-facing camera and sensors (colloquially known as «notch»; since the iPhone X from 2017), the exclusion of a charging wall adapter from the scope of delivery (since the iPhone 12 from 2019), and a camera user interface with circular and usually solid-colour shutter button and a camera mode selector using perpendicular text and separate camera modes for photo and video (since iOS 7 from 2013).[183][184][185][186][187][188]

Other developments in the 2020s

In 2020, the first smartphones featuring high-speed 5G network capability were announced.[189]

Since 2020, smartphones have decreasingly been shipped with rudimentary accessories like a power adapter and headphones that have historically been almost invariably within the scope of delivery. This trend was initiated with Apple’s iPhone 12, followed by Samsung and Xiaomi on the Galaxy S21 and Mi 11 respectively, months after having mocked the same through advertisements. The reason cited is reducing environmental footprint, though reaching raised charging rates supported by newer models demands a new charger shipped through separate packaging with its own environmental footprint.[190]

Mobile/desktop convergence: the Librem 5 smartphone can be used as a basic desktop computer

With the development of the PinePhone and Librem 5 in the 2020s, there are intensified efforts to make open source GNU/Linux for smartphones a major alternative to iOS and Android.[191][192][193] Moreover, associated software enabled convergence (beyond convergent[194] and hybrid apps) by allowing the smartphones to be used like a desktop computer when connected to a keyboard, mouse and monitor.[195][196][197][198]

In the early 2020s, manufacturers began to integrate satellite connectivity into smartphone devices for use in remote areas, where local terrestrial communication infrastructures, such as landline and cellular networks, are not available. Due to the antenna limitations in the conventional phones, in the early stages of implementation satellite connectivity would be limited to the satellite messaging and satellite emergency services.[199][200]

Hardware

Smartphone with infrared transmitter on top for use as remote control

A typical smartphone contains a number of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chips,[201] which in turn contain billions of tiny MOS field-effect transistors (MOSFETs).[202] A typical smartphone contains the following MOS IC chips:[201]

- Application processor (CMOS system-on-a-chip)

- Flash memory (floating-gate MOS memory)

- Cellular modem (baseband RF CMOS)

- RF transceiver (RF CMOS)

- Phone camera image sensor (CMOS image sensor)

- Power management integrated circuit (power MOSFETs)

- Display driver (LCD or LED driver)

- Wireless communication chips (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, GPS receiver)

- Sound chip (audio codec and power amplifier)

- Gyroscope

- Capacitive touchscreen controller (ASIC and DSP)[201][203][204]

- RF power amplifier (LDMOS)[205][206][207]

Some are also equipped with an FM radio receiver, a hardware notification LED, and an infrared transmitter for use as remote control. Few have additional sensors such as thermometer for measuring ambient temperature, hygrometer for humidity, and a sensor for ultraviolet ray measurement.

Few exotic smartphones designed around specific purposes are equipped with uncommon hardware such as a projector (Samsung Beam i8520 and Samsung Galaxy Beam i8530), optical zoom lenses (Samsung Galaxy S4 Zoom and Samsung Galaxy K Zoom), thermal camera, and even PMR446 (walkie-talkie radio) transceiver.[208][209]

Central processing unit

Smartphones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments. In smartphones, the CPU is typically integrated in a CMOS (complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor) system-on-a-chip (SoC) application processor.[201]

The performance of mobile CPU depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[210] but also on the memory hierarchy. Because of these challenges, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Buttons

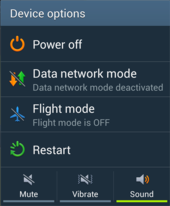

«Device options» menu of Samsung Mobile’s TouchWiz user interface as of 2013, accessed by holding the power button for a second

Smartphones are typically equipped with a power button and volume buttons. Some pairs of volume buttons are unified. Some are equipped with a dedicated camera shutter button. Units for outdoor use may be equipped with an «SOS» emergency call and «PTT» (push-to-talk button). The presence of physical front-side buttons such as the home and navigation buttons has decreased throughout the 2010s, increasingly becoming replaced by capacitive touch sensors and simulated (on-screen) buttons.[211]

As with classic mobile phones, early smartphones such as the Samsung Omnia II were equipped with buttons for accepting and declining phone calls. Due to the advancements of functionality besides phone calls, these have increasingly been replaced by navigation buttons such as «menu» (also known as «options»), «back», and «tasks». Some early 2010s smartphones such as the HTC Desire were additionally equipped with a «Search» button (🔍) for quick access to a web search engine or apps’ internal search feature.[212]

Since 2013, smartphones’ home buttons started integrating fingerprint scanners, starting with the iPhone 5s and Samsung Galaxy S5.

Functions may be assigned to button combinations. For example, screenshots can usually be taken using the home and power buttons, with a short press on iOS and one-second holding Android OS, the two most popular mobile operating systems. On smartphones with no physical home button, usually the volume-down button is instead pressed with the power button. Some smartphones have a screenshot and possibly screencast shortcuts in the navigation button bar or the power button menu.[213][214][215]

Display

One of the main characteristics of smartphones is the screen. Depending on the device’s design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device’s front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017, as well as the aim to eliminate bezels by extending the display surface to as close to the edges as possible.

Screen sizes

Screen sizes are measured in diagonal inches. Phones with screens larger than 5.2 inches are often called «phablets». Smartphones with screens over 4.5 inches in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and «edge-to-edge» designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[216][217][218]

Panel types

Liquid-crystal displays (LCDs) and organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays are the most common. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[219] and Apple’s Force Touch system. A few phones, such as the YotaPhone prototype, are equipped with a low-power electronic paper rear display, as used in e-book readers.

Alternative input methods

Some devices are equipped with additional input methods such as a stylus for higher precision input and hovering detection, and/or a self-capacitive touch screens layer for floating finger detection. The latter has been implemented on few phones such as the Samsung Galaxy S4, Note 3, S5, Alpha, and Sony Xperia Sola, making the Galaxy Note 3 the only smartphone with both so far.

Hovering can enable preview tooltips such as on the video player’s seek bar, in text messages, and quick contacts on the dial pad, as well as lock screen animations, and the simulation of a hovering mouse cursor on web sites.[220][221][222]

Some styluses support hovering as well and are equipped with a button for quick access to relevant tools such as digital post-it notes and highlighting of text and elements when dragging while pressed, resembling drag selection using a computer mouse. Some series such as the Samsung Galaxy Note series and LG G Stylus series have an integrated tray to store the stylus in.[223]

Few devices such as the iPhone 6s until iPhone Xs and Huawei Mate S are equipped with a pressure-sensitive touch screen, where the pressure may be used to simulate a gas pedal in video games, access to preview windows and shortcut menus, controlling the typing cursor, and a weight scale, the latest of which has been rejected by Apple from the App Store.[224][225]

Some early 2010s HTC smartphones such as the HTC Desire (Bravo) and HTC Legend are equipped with an optical track pad for scrolling and selection.[226]

Notification light

Many smartphones except Apple iPhones are equipped with low-power light-emitting diodes besides the screen that are able to notify the user about incoming messages, missed calls, low battery levels, and facilitate locating the mobile phone in darkness, with marginial power consumption.

To distinguish between the sources of notifications, the colour combination and blinking pattern can vary. Usually three diodes in red, green, and blue (RGB) are able to create a multitude of colour combinations.

Sensors

Smartphones are equipped with a multitude of sensors to enable system features and third-party applications.

Common sensors

Accelerometers and gyroscopes enable automatic control of screen rotation. Uses by third-party software include bubble level simulation. An ambient light sensor allows for automatic screen brightness and contrast adjustment, and an RGB sensor enables the adaption of screen colour.

Many mobile phones are also equipped with a barometer sensor to measure air pressure, such as Samsung since 2012 with the Galaxy S3, and Apple since 2014 with the iPhone 6. It allows estimating and detecting changes in altitude.

A magnetometer can act as a digital compass by measuring Earth’s magnetic field.

Rare sensors

Samsung equips their flagship smartphones since the 2014 Galaxy S5 and Galaxy Note 4 with a heart rate sensor to assist in fitness-related uses and act as a shutter key for the front-facing camera.[227]

So far, only the 2013 Samsung Galaxy S4 and Note 3 are equipped with an ambient temperature sensor and a humidity sensor, and only the Note 4 with an ultraviolet radiation sensor which could warn the user about excessive exposure.[228][229]

A rear infrared laser beam for distance measurement can enable time-of-flight camera functionality with accelerated autofocus, as implemented on select LG mobile phones starting with LG G3 and LG V10.

Due to their currently rare occurrence among smartphones, not much software to utilize these sensors has been developed yet.

Storage

While eMMC (embedded multi media card) flash storage was most commonly used in mobile phones, its successor, UFS (Universal Flash Storage) with higher transfer rates emerged throughout the 2010s for upper-class devices.[230]

- Capacity

While the internal storage capacity of mobile phones has been near-stagnant during the first half of the 2010s, it has increased steeper during its second half, with Samsung for example increasing the available internal storage options of their flagship class units from 32 GB to 512 GB within only 21⁄2 years between 2016 and 2018.[231][232][233][234]

Memory cards

Inserted memory and SIM cards

The space for data storage of some mobile phones can be expanded using MicroSD memory cards, whose capacity has multiplied throughout the 2010s (→ SD card § 2009–2018: SDXC). Benefits over USB on the go storage and cloud storage include offline availability and privacy, not reserving and protruding from the charging port, no connection instability or latency, no dependence on voluminous data plans, and preservation of the limited rewriting cycles of the device’s permanent internal storage. Large amounts of data can be moved immediately between devices by changing memory cards, and data can be read externally should the smartphone be inoperable.[235][236]

In case of technical defects which make the device unusable or unbootable as a result of liquid damage, fall damage, screen damage, bending damage, malware, or bogus system updates,[237] etc., data stored on the memory card is likely rescueable externally, while data on the inaccessible internal storage would be lost. A memory card can usually[b] immediately be re-used in a different memory-card-enabled device with no necessity for prior file transfers.

Some dual-SIM mobile phones are equipped with a hybrid slot, where one of the two slots can be occupied by either a SIM card or a memory card. Some models, typically of higher end, are equipped with three slots including one dedicated memory card slot, for simultaneous dual-SIM and memory card usage.[238]

- Physical location

The location of both SIM and memory card slots vary among devices, where they might be located accessibly behind the back cover or else behind the battery, the latter of which denies hot swapping.[239][240]

Mobile phones with non-removable rear cover typically house SIM and memory cards in a small tray on the handset’s frame, ejected by inserting a needle tool into a pinhole.[241]

Some earlier mid-range phones such as the 2011 Samsung Galaxy Fit and Ace have a sideways memory card slot on the frame covered by a cap that can be opened without tool.[242]

File transfer

Originally, mass storage access was commonly enabled to computers through USB. Over time, mass storage access was removed, leaving the Media Transfer Protocol as protocol for USB file transfer, due to its non-exclusive access ability where the computer is able to access the storage without it being locked away from the mobile phone’s software for the duration of the connection, and no necessity for common file system support, as communication is done through an abstraction layer.

However, unlike mass storage, Media Transfer Protocol lacks parallelism, meaning that only a single transfer can run at a time, for which other transfer requests need to wait to finish. This, for example, denies browsing photos and playing back videos from the device during an active file transfer. Some programs and devices lack support for MTP. In addition, the direct access and random access of files through MTP is not supported. Any file is wholly downloaded from the device before opened.[243]

Sound

Some audio quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[244][245] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over WiFi.[246] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear.

Some mobile phones such as the HTC One M8 and the Sony Xperia Z2 are equipped with stereophonic speakers to create spacial sound when in horizontal orientation.[247]

Audio connector

The 3.5mm headphone receptible (coll. «headphone jack«) allows the immediate operation of passive headphones, as well as connection to other external auxiliary audio appliances. Among devices equipped with the connector, it is more commonly located at the bottom (charging port side) than on the top of the device.

The decline of the connector’s availability among newly released mobile phones among all major vendors commenced in 2016 with its lack on the Apple iPhone 7. An adapter reserving the charging port can retrofit the plug.

Battery-powered, wireless Bluetooth headphones are an alternative. Those tend to be costlier however due to their need for internal hardware such as a Bluetooth transceiver and a battery with a charging controller, and a Bluetooth coupling is required ahead of each operation.[248]

Battery

A smartphone typically uses a lithium-ion battery due to its high energy density.[249][250][251]

Batteries chemically wear down as a result of repeated charging and discharging throughout ordinary usage, losing both energy capacity and output power, which results in loss of processing speeds followed by system outages.[252] Battery capacity may be reduced to 80% after few hundred recharges, and the drop in performance accelerates with time.[253][254]

Some mobile phones are designed with batteries that can be interchanged upon expiration by the end user, usually by opening the back cover. While such a design had initially been used in most mobile phones, including those with touch screen that were not Apple iPhones, it has largely been usurped throughout the 2010s by permanently built-in, non-replaceable batteries; a design practice criticized for planned obsolescence.[255][256]

Charging

Due to limitations of electrical currents that existing USB cables’ copper wires could handle, charging protocols which make use of elevated voltages such as Qualcomm Quick Charge and MediaTek Pump Express have been developed to increase the power throughput for faster charging, to maximize the usage time without restricted ergonomy and to minimize the time a device needs to be attached to a power source.

The smartphone’s integrated charge controller (IC) requests the elevated voltage from a supported charger. «VOOC» by Oppo, also marketed as «dash charge», took the counter approach and increased current to cut out some heat produced from internally regulating the arriving voltage in the end device down to the battery’s charging terminal voltage, but is incompatible with existing USB cables, as it requires the thicker copper wires of high-current USB cables. Later, USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) was developed with the aim to standardize the negotiation of charging parameters across devices of up to 100 Watts, but is only supported on cables with USB-C on both endings due to the connector’s dedicated PD channels.[257]

While charging rates have been increasing, with 15 watts in 2014,[258] 20 Watts in 2016,[259] and 45 watts in 2018,[260] the power throughput may be throttled down significantly during operation of the device.[261][c]

Wireless charging has been widely adapted, allowing for intermittent recharging without wearing down the charging port through frequent reconnection, with Qi being the most common standard, followed by Powermat. Due to the lower efficiency of wireless power transmission, charging rates are below that of wired charging, and more heat is produced at similar charging rates.

By the end of 2017, smartphone battery life has become generally adequate;[262] however, earlier smartphone battery life was poor due to the weak batteries that could not handle the significant power requirements of the smartphones’ computer systems and color screens.[263][264][265]

Smartphone users purchase additional chargers for use outside the home, at work, and in cars and by buying portable external «battery packs». External battery packs include generic models which are connected to the smartphone with a cable, and custom-made models that «piggyback» onto a smartphone’s case. In 2016, Samsung had to recall millions of the Galaxy Note 7 smartphones due to an explosive battery issue.[266] For consumer convenience, wireless charging stations have been introduced in some hotels, bars, and other public spaces.[267]

Cameras

Cameras have become standard features of smartphones. As of 2019 phone cameras are now a highly competitive area of differentiation between models, with advertising campaigns commonly based on a focus on the quality or capabilities of a device’s main cameras.

Images are usually saved in the JPEG file format; some high-end phones since the mid-2010s also have RAW imaging capability.[268][269]

Space constraints

Typically smartphones have at least one main rear-facing camera and a lower-resolution front-facing camera for «selfies» and video chat. Owing to the limited depth available in smartphones for image sensors and optics, rear-facing cameras are often housed in a «bump» that’s thicker than the rest of the phone. Since increasingly thin mobile phones have more abundant horizontal space than the depth that is necessary and used in dedicated cameras for better lenses, there’s additionally a trend for phone manufacturers to include multiple cameras, with each optimized for a different purpose (telephoto, wide angle, etc.).

Viewed from back, rear cameras are commonly located at the top center or top left corner. A cornered location benefits by not requiring other hardware to be packed around the camera module while increasing ergonomy, as the lens is less likely to be covered when held horizontally.

Modern advanced smartphones have cameras with optical image stabilisation (OIS), larger sensors, bright lenses, and even optical zoom plus RAW images. HDR, «Bokeh mode» with multi lenses and multi-shot night modes are now also familiar.[270] Many new smartphone camera features are being enabled via computational photography image processing and multiple specialized lenses rather than larger sensors and lenses, due to the constrained space available inside phones that are being made as slim as possible.

Dedicated camera button

Some mobile phones such as the Samsung i8000 Omnia 2, some Nokia Lumias and some Sony Xperias are equipped with a physical camera shutter button.

Those with two pressure levels resemble the point-and-shoot intuition of dedicated compact cameras. The camera button may be used as a shortcut to quickly and ergonomically launch the camera software, as it is located more accessibly inside a pocket than the power button.

Back cover materials

Back covers of smartphones are typically made of polycarbonate, aluminium, or glass. Polycarbonate back covers may be glossy or matte, and possibly textured, like dotted on the Galaxy S5 or leathered on the Galaxy Note 3 and Note 4.

While polycarbonate back covers may be perceived as less «premium» among fashion- and trend-oriented users, its utilitarian strengths and technical benefits include durability and shock absorption, greater elasticity against permanent bending like metal, inability to shatter like glass, which facilitates designing it removable; better manufacturing cost efficiency, and no blockage of radio signals or wireless power like metal.[271][272][273][274]

Accessories

A wide range of accessories are sold for smartphones, including cases, memory cards, screen protectors, chargers, wireless power stations, USB On-The-Go adapters (for connecting USB drives and or, in some cases, a HDMI cable to an external monitor), MHL adapters, add-on batteries, power banks, headphones, combined headphone-microphones (which, for example, allow a person to privately conduct calls on the device without holding it to the ear), and Bluetooth-enabled powered speakers that enable users to listen to media from their smartphones wirelessly.

Cases range from relatively inexpensive rubber or soft plastic cases which provide moderate protection from bumps and good protection from scratches to more expensive, heavy-duty cases that combine a rubber padding with a hard outer shell. Some cases have a «book»-like form, with a cover that the user opens to use the device; when the cover is closed, it protects the screen. Some «book»-like cases have additional pockets for credit cards, thus enabling people to use them as wallets.

Accessories include products sold by the manufacturer of the smartphone and compatible products made by other manufacturers.

However, some companies, like Apple, stopped including chargers with smartphones in order to «reduce carbon footprint,» etc., causing many customers to pay extra for charging adapters.

Software

Mobile operating systems

A mobile operating system (or mobile OS) is an operating system for phones, tablets, smartwatches, or other mobile devices.

Mobile operating systems combine features of a personal computer operating system with other features useful for mobile or handheld use; usually including, and most of the following considered essential in modern mobile systems; a touchscreen, cellular, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi Protected Access, Wi-Fi, Global Positioning System (GPS) mobile navigation, video- and single-frame picture cameras, speech recognition, voice recorder, music player, near field communication, and infrared blaster. By Q1 2018, over 383 million smartphones were sold with 85.9 percent running Android, 14.1 percent running iOS and a negligible number of smartphones running other OSes.[275] Android alone is more popular than the popular desktop operating system Windows, and in general, smartphone use (even without tablets) exceeds desktop use. Other well-known mobile operating systems are Flyme OS and Harmony OS.

Mobile devices with mobile communications abilities (e.g., smartphones) contain two mobile operating systems – the main user-facing software platform is supplemented by a second low-level proprietary real-time operating system which operates the radio and other hardware. Research has shown that these low-level systems may contain a range of security vulnerabilities permitting malicious base stations to gain high levels of control over the mobile device.[276]

Mobile app

A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term «app» is a short-form of the term «software application».[277]

Application stores

The introduction of Apple’s App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google’s Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store) and RIM’s BlackBerry App World, Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[278]

List of current smartphone brands

- Apple iPhone

- Asus

- Gionee

- Google Pixel

- Honor

- HTC

- Huawei

- Infinix

- iQOO

- Itel

- Lenovo

- Meizu

- Motorola

- Nokia

- Nothing

- Nubia

- OnePlus

- Oppo

- POCO

- Realme

- Redmi

- Samsung Galaxy

- Sharp

- Sony Xperia

- Tecno

- Umidigi

- Vivo

- Xiaomi

- ZTE

Sales

Since 1996, smartphone shipments have had positive growth. In November 2011, 27% of all photographs created were taken with camera-equipped smartphones.[279] In September 2012, a study concluded that 4 out of 5 smartphone owners use the device to shop online.[280] Global smartphone sales surpassed the sales figures for feature phones in early 2013.[3] Worldwide shipments of smartphones topped 1 billion units in 2013, up 38% from 2012’s 725 million, while comprising a 55% share of the mobile phone market in 2013, up from 42% in 2012. In 2013, smartphone sales began to decline for the first time.[281][282] In Q1 2016 for the first time the shipments dropped by 3 percent year on year. The situation was caused by the maturing China market.[283] A report by NPD shows that fewer than 10% of US citizens have bought $1,000+ smartphones, as they are too expensive for most people, without introducing particularly innovative features, and amid Huawei, Oppo and Xiaomi introducing products with similar feature sets for lower prices.[284][285][286] In 2019, smartphone sales declined by 3.2%, the largest in smartphone history, while China and India were credited with driving most smartphone sales worldwide.[287] It is predicted that widespread adoption of 5G will help drive new smartphone sales.[288][289]

By manufacturer

In 2011, Samsung had the highest shipment market share worldwide, followed by Apple. In 2013, Samsung had 31.3% market share, a slight increase from 30.3% in 2012, while Apple was at 15.3%, a decrease from 18.7% in 2012. Huawei, LG and Lenovo were at about 5% each, significantly better than 2012 figures, while others had about 40%, the same as the previous years figure. Only Apple lost market share, although their shipment volume still increased by 12.9%; the rest had significant increases in shipment volumes of 36–92%.[290]

In Q1 2014, Samsung had a 31% share and Apple had 16%.[291] In Q4 2014, Apple had a 20.4% share and Samsung had 19.9%.[292] In Q2 2016, Samsung had a 22.3% share and Apple had 12.9%.[293] In Q1 2017, IDC reported that Samsung was first placed, with 80 million units, followed by Apple with 50.8 million, Huawei with 34.6 million, Oppo with 25.5 million and Vivo with 22.7 million.[294]