Доктор Мартин Купер со своей первой моделью мобильного телефона 1973 г. Фото 2007 г.

Обычно об истории создания мобильного телефона рассказывают примерно так.

3 апреля 1973 года глава подразделения мобильной связи Motorola Мартин Купер, прогуливаясь по центру Манхеттена, решил позвонить по мобильнику. Мобильник назывался Dyna-TAC и был похож на кирпич, который весил более килограмма, а работал в режиме разговора всего полчаса.

До этого сын основателя компании Motorola Роберт Гелвин, занимавший в те далекие времена пост исполнительного директора этой фирмы, выделил 15 миллионов долларов и дал подчиненным срок 10 лет на то, чтобы создать устройство, которое пользователь сможет носить с собой. Первый работающий образец появился всего через пару месяцев. Успеху Мартин Купера, пришедшего в фирму в 1954 году рядовым инженером, способствовало то, что с 1967 года он занимался разработкой портативных раций. Они-то и привели к идее мобильного телефона.

Считается, что до этого момента других мобильных телефонных аппаратов, которые человек может носить с собой, как часы или записную книжку, не существовало. Были портативные рации, были «мобильные» телефоны, которыми можно было пользоваться в автомобиле или поезде, а вот такого, чтобы просто ходить по улице — нет.

Более того, до начала 1960-х годов многие компании вообще отказывались проводить исследования в области создания сотовой связи, поскольку приходили к выводу, что, в принципе, невозможно создать компактный сотовый телефонный аппарат. И никто из специалистов этих компаний не обратил внимание на то, что по другую сторону «железного занавеса» в научно-популярных журналах стали появляться фотографии, где был изображен… человек, говорящий по мобильному телефону. (Для сомневающихся будут приводиться номера журналов, где опубликованы снимки, чтобы каждый мог убедиться, что это не графический редактор).

Мистификация? Шутка? Пропаганда? Попытка дезинформировать западных производителей электроники (эта промышленность, как известно, имела стратегическое военное значение)? Может быть, речь идет просто об обыкновенной рации? Однако дальнейшие поиски привели к совершенно неожиданному выводу — Мартин Купер был не первым в истории человеком, позвонившим по мобильному телефону. И даже не вторым.

Инженер Леонид Куприянович демонстрирует возможности мобильного телефона. «Наука и жизнь», 10, 1958 год.

Человека на снимке из журнала «Наука и жизнь» звали Леонид Иванович Куприянович, и именно он оказался человеком, сделавшим звонок по мобильному телефону за 15 лет раньше Купера. Но прежде чем речь пойдет об этом, вспомним, что основные принципы мобильной связи имеют очень и очень давнюю историю

Собственно, попытки придать телефону мобильность появились вскоре после возникновения. Были созданы полевые телефоны с катушками для быстрой прокладки линии, делались попытки оперативно обеспечит связь из автомобиля, набрасывая провода на идущую вдоль шоссе линию или подключаясь к розетке на столбе. Из всего этого сравнительно широкое распространение нашли только полевые телефоны (на одной из мозаик станции метро «Киевская» в Москве современные пассажиры иногда принимают полевой телефон за мобильник и ноутбук).

Обеспечить подлинную мобильность телефонной связи стало возможно лишь после появления радиосвязи в УКВ диапазоне. К 30-м годам появились передатчики, которые человек мог без особого труда носить на спине или держать в руках — в частности, они использовались американской радиокомпанией NBC для оперативных репортажей с места событий. Однако соединения с автоматическими телефонными станциями такие средства связи еще не обеспечивали.

Портативный УКВ передатчик. «Радиофронт», 16, 1936

Во время Великой Отечественной советский ученый и изобретатель Георгий Ильич Бабат в блокадном Ленинграде предложил так называемый «монофон» — автоматический радиотелефон, работающий в сантиметровом дипазоне 1000-2000 МГц (сейчас для стандарта GSM используются частоты 850, 900, 1800 и 1900 Гц), номер которого кодируется в самом телефоне, снабжен буквенной клавиатурой и имеет также функции диктофона и автоответчика. «Он весит не больше, чем пленочный аппарат «лейка»» — писал Г. Бабат в своей статье «Монофон» в журнале «Техника-Молодежи» № 7-8 за 1943 год: «Где бы ни находился абонент — дома, в гостях или на работе, в фойе театра, на трибуне стадиона, наблюдая состязания — всюду он может включить свой индивидуальный монофон в одно из многочисленных окончаний разветвлений волновой сети. К одному окончанию могут подлючиться несколько абонентов, и сколько бы их ни было, они не помешают друг другу». В связи с тем, что принципы сотовой связи к тому времени еще не были изобретены, Бабат предлагал использовать для связи мобильников с базовой станцией разветвленную сеть СВЧ — волноводов.

Г. Бабат, предложивший идею мобильного телефона

В декабре 1947 года сотрудники американской фирмы Bell Дуглас Ринг и Рей Янг предложили принцип шестиугольных ячеек для мобильной телефонии. Это произошло как раз в разгар активных попыток создать телефон, с помощью которого можно звонить из автомобиля. Первый такой сервис был запущен в 1946 году в городе Сент-Луис компания AT&T Bell Laboratories, а в 1947 году была запущена система с промежуточными станциями вдоль шоссе, позволявшая звонить из автомобиля на пути из Нью-Йорка в Бостон. Однако из-за несовершенства и дороговизны эти системы не были коммерчески успешными. В 1948 году еще одна амеиканская телефонная компания в Ричмонде сумела наладить сервис автомобильных радиотелефонов с автоматическим набором номера, что уже было лучше. Вес аппаратуры таких систем составлял десятки килограмм и размещалась она в багажнике, так что мысли о карманном варианте о взгляде на нее у неискушенного человека не возникало.

Отечественный автомобильный радиотелефон. Радио, 1947, № 5.

Тем не менее, как было отмечено в том же 1946 году в журнале «Наука и жизнь», № 10, отечественные инженеры Г. Шапиро и И. Захарченко разработали систему телефонной связи из движущегося автомобиля с городской сетью, мобильный аппарат которой имел мощность всего в 1 ватт и умещался под щитком приборов. Питание было от автомобильного аккумулятора.

К радиоприемнику, установленному на городской телефонной станции, был подключен номер телефона, присвоенный автомобилю. Для вызова городского абонента надо было включить аппарат в автомобиле, который посылал в эфир свои позывные. Они воспринимались базовой станцией на городской АТС и тотчас же включался телефонный аппарат, который работал, как обычный телефон. При вызове автомобиля городской абонент набирал номер, это приводило в действие базовую станцию, сигнал которой воспринимался аппаратом на автомобиле.

Как видно из описания, данная система представляла собой что-то вроде радиотрубки. В ходе проведенных в 1946 году опытов в Москве была достигнута дальность действия аппарата свыше 20 км, а также осуществлен разговор с Одессой при отличной слышимости. В дальнейшем изобретатели работали над увеличением радиуса базовой станции до 150 км.

Ожидалось, что телефон системы Шапиро и Захарченко будет широко использоваться при работе пожарных команд, подразделений ПВО, милиции, скорой медицинской и технической помощи. Однако в дальнейшем сведений о развитии системы не появлялось. Можно предположить, что для аварийно-спасательных служб было признано более целесообразным использовать свои ведомственные системы связи, нежели использовать ГТС.

Алфред Гросс мог стать создателем первого мобильника.

В США первым попытался сделать невозможное изобретатель Алфред Гросс. Он с 1939 года увлекался созданием портативных раций, которые десятилетия спустя получили название «уоки-токи». В 1949 году он создал прибор на базе портативной рации, который назвался «беспроводным дистанционным телефоном». Прибор можно было носить с собой, и он подавал владельцу сигнал подойти к телефону. Считается, что это был первый простейший пейджер. Гросс даже внедрил его в одной из больниц в Нью-Йорке, но телефонные компании не проявили интереса к этой новинке, как и к другим его идеям в этом направлении. Так Америка потеряла шанс стать родиной первого практически действующего мобильного телефона.

Однако эти идеи получили развитие по другую сторону Атлантического океана, в СССР. Итак, одним из тех, кто продолжил поиски в области мобильной связи в нашей стране, оказался Леонид Куприянович. О его личности пресса того времени сообщала очень мало. Было известно, что он жил в Москве, деятельность его пресса скупо характеризовала как «радиоинженер» или «радиолюбитель». Известно также, что Куприяновича можно было считать по тому времени успешным человеком — в начале 60-х у него была машина.

Созвучность фамилий Куприяновича и Купера — лишь начальное звено в цепи странных совпадений в судьбе этих личностей. Куприянович, как Купер и Гросс, тоже начинал с миниатюрных раций — он делал их с середины 50-х годов, и многие его конструкции поражают даже сейчас — как своими габаритами, так и простотой и оригинальностью решений. Радиостанция на лампах, созданная им в 1955 году, весила столько же, сколько первые транзисторные «уоки-токи» начала 60-х.

Карманная рация Куприяновича 1955 года

В 1957 году Куприянович демонстрирует еще более удивительную вещь — рацию размером со спичечный коробок и весом всего 50 грамм (вместе с источниками питания), которая может работать без смены питания 50 часов и обеспечивает связь на дальности двух километров — вполне под стать продукции 21 века, которую можно видеть на витринах нынешних салонов связи (снимок из журнала ЮТ, 3, 1957). Как свидетельствовала публикация в ЮТ, 12, 1957 г., в этой радиостанции были использованы ртутные или марганцевые элементы питания.

При этом Куприянович не только обошелся без микросхем, которых в то время просто не было, но и вместе с транзисторами использовал миниатюрные лампы. В 1957 и в 1960 годах выходит первое и второе издание его книги для радиолюбителей, с многообещающим названием — «Карманные радиостанции».

В издании 1960 года описывается простая радиостанция всего на трех транзисторах, которую можно носить на руке — почти как знаменитая рация-часы из фильма «Мертвый сезон». Автор предлагал ее для повторения туристам и грибникам, но в жизни к этой конструкции Куприяновича интерес проявили в основном студенты — для подсказок на экзаменах, что даже вошло в эпизод гайдаевской кинокомедии «Операция Ы»

Наручная рация Куприяновича

И, так же, как и Купера, карманные рации навели Куприяновича сделать такой радиотелефон, с которого можно было бы позвонить на любой городской телефонный аппарат, и который можно брать с собой куда угодно. Пессимистические настроения зарубежных фирм не могли остановить человека, который умел делать рации со спичечный коробок.

В 1957 году Л.И. Куприянович получил авторское свидетельство на «Радиофон» — автоматический радиотелефон с прямым набором. Через автоматическую телефонную радиостанцию с этого аппарата можно было соединяться с любым абонентом телефонной сети в пределах действия передатчика «Радиофона». К тому времени был готов и первый действующий комплект аппаратуры, демонстрирующий принцип работы «Радиофона», названный изобретателем ЛК-1 (Леонид Куприянович, первый образец).

ЛК-1 по нашим меркам еще было трудно назвать мобильником, но на современников производил большое впечатление. «Телефонный аппарат невелик по габаритам, вес его не превышает трех килограммов» — писала «Наука и жизнь». «Батареи питания размещаются внутри корпуса аппарата; срок непрерывного использования их равен 20-30 часам. ЛК-1 имеет 4 специальные радиолампы, так что отдаваемая антенной мощность достаточна для связи на коротких волнах в роеделах 20-30 километров На аппарате размещены 2 антенны; на передней его панели установлены 4 переключателя вызова, микрофон (снаружи которого подключаются наушники) и диск для набора номера».

Авторское свидетельст-во 115494 от 1.11.1957

Так же, как и в современном сотовом телефоне, аппарат Куприяновича соединялся с городской телефонной сетью через базовую станцию (автор называл ее АТР — автоматическая телефонная радиостанция), которая принимала сигналы от мобильников в проводную сеть и передавала из проводнйо сети на мобильники. 50 лет назад принципы работы мобильника описывались для неискушенных чистателей просто и образно: «Соединение АТР с любым абонентом происходит, как и у обычного телефона, только ее работой мы управляем на расстоянии».

Для работы мобильника с базовой станцией использовались четыре канала связи на четырех частотах: два канала служили для передачи и приема звука, один для набора номера и один для отбоя.

Первый мобильник Куприяновича. («Наука и жизнь, 8, 1957 г.»). Справа — базовая станция.

У читателя может возникнуть подозрение, что ЛК-1 был простой радиотрубкой для телефона. Но, оказывается, это не так. »Невольно возникает вопрос: не будут ли мешать друг другу несколько одновременно работающих ЛК-1?» — пишет все та же «Наука и жизнь». «Нет, так как в этом случае для аппарата используют разные тональные частоты, заставляющие срабатывать на АТР свои реле (тональные частоты будут передаваться на одной волне). Частоты передач и приема звука для каждого аппарата будут свои, чтобы избежать их взаимного влияния».

Таким образом, в ЛК-1 имелось кодирование номера в самом телефонном аппарате, а не в зависимости от проводной линии, что позволяет его с полным основанием рассматривать в качестве первого мобильного телефона. Правда, судя по описанию, это кодирование было весьма примитивным, и количество абонентов, имеющих возможность работы через одну АТР получалось на первых порах весьма ограниченным. Кроме того в первом демонстраторе АТР просто включалась в обычную телефонную параллельно существующей абонентской точке — это позволяло приступить к опытам, не внося изменений в городскую АТС, но затрудняло одновременный «выход в город» с нескольких трубок. Впрочем, в 1957 году ЛК-1 существовал еще только в одном экземпляре.

Пользоваться первым мобильником было не так удобно, как сейчас. («ЮТ, 7, 1957″)

Тем не менее, практическая возможность реализации носимого мобильника и организации сервиса такой мобильной связи хотя бы в виде ведомственных коммутаторов была доказана. «Радиус действия аппарата…несколько десятков км.»- пишет Леонид Куприянович в заметке для июльского номера журнала «Юный техник» 1957 года. » Если же в этих пределах будет лишь одно приемное устройство, этого будет достаточно, чтобы разговаривать с любым из жителей города, имеющим телефон, и за сколько угодно километров.» «Радиотелефоны …могут быть использованы на автотранспорте, на самолетах и кораблях. Пассажиры смогут приямо из саиолета позвонить домой, на работу, заказать номер в гостинице. Он найдет применение у туристов, строителей, охотников и т.д.».

Комикс в журнале ЮТ, 7, 1957 г: Тонтон с Московского фестиваля звонит в Париж семье по мобильнику. Теперь этим никого не удивить.

Кроме того, Куприянович предвидел, что мобильный телефон сумеет вытеснить и телефоны, встраиваемые в автомобили. При этом молодой изобретатель сразу использовал нечто вроде гарнитуры «hands free», т.е. вместо наушника использовалась громкая связь. В интервью М.Мельгуновой, опубликованной в журнале «За рулем», 12, 1957 г. Куприянович предполагал производить внедрение мобильных телефонов в два этапа. «Вначале, пока радиотелефонов немного, дополнительный радиоприбор устанавливается обычно возле домашнего телефона автолюбителя. Но позднее, когда таких аппаратов будут тысячи, АТР уже будет работать не на один радиотелефон, а на сотни и тысячи. Причем все они не помешают друг другу, так как каждый из них будет иметь свою тональную частоту, заставляющую работать свое реле.» Таким образом, Куприянович по существу, позиционировал сразу два вида бытовой техники — простые радиотрубки, которые было проще запустить в производство, и сервис мобильных телефонов, при котором одна базовая станция обслуживает тысячи абонентов.

Куприянович с ЛК-1 в автомобиле. Справа от аппарата — динамик громкой связи. «За рулем», 12, 1957 г.

Можно удивляться, насколько точно Куприянович более полувека назад представлял себе, как широко войдет мобильный телефон в нашу повседневную жизнь.

«Взяв такой радиофон с собою, вы берете, по существу, обычный телефонный аппарат, но без проводов» — напишет он спустя пару лет. «Где бы вы не находились, вас всегда можно будет разыскать по телефону, стоит только с любого городского телефона (даже с телефона-автомата) набрать известный номер вашего радиофона. У вас в кармане раздается телефонный звонок, и вы начинаете разговор. В случае необходимости вы можете прямо из трамвая, троллейбуса, автобуса набрать любой городской телефонный номер, вызвать «Скорую помощь», пожарную или аварийную автомашины, связаться с домом…»

Трудно поверить, что эти слова написаны человеком, не побывавшем в 21 веке. Впрочем, для Куприяновича не было необходимости путешествовать в будущее. Он его строил.

Блок-схема упрощенного варианта ЛК-1

В 1958 году Купрянович по просьбам радиолюбителей публикует в февральском номере журнале «Юный техник» упрощенную конструкцию аппарата, АТР которого может работать только с одной радиотрубкой и не имеет функции междугородних вызовов.

Принципиальная схема упрощенного варианта ЛК-1

схема дифференциального трансформатора

Пользование таким мобильником было несколько сложнее, чем современными. Перед вызовом абонента надо было, помимо приемника, включить на «трубке» также и передатчик. Услышав в наушнике длинный телефонный гудок и сделав соответствующие переключения, можно было переходить к набору номера. Но все равно это было удобнее, чем на радиостанциях того времени, так как не надо было переключаться с приема на передачу и заканчивать каждую фразу словом «Прием!». По окончании разговора передатчик нагрузки отключался сам для экономии батарей.

Публикуя описание в журнале для юношества, Куприянович не боялся конкуренции. К этому времени у него уже готова новая модель аппарата, которую по тем временам можно считать революционной.

ЛK-1 и базовая станция. ЮТ, 2, 1958

Модель мобильного телефона 1958 года вместе с источником питания весила всего 500 грамм.

Этот весовой рубеж был снова взят мировой технической мыслью только… 6 марта 1983 года, т.е. четверть века спустя. Правда, модель Куприяновича была не столь изящна и представляла собой коробку с тумблерами и круглым диском номеронабирателя, к которой на проводе подключалась обычная телефонная трубка. Получалось, что при разговоре были либо заняты обе руки, либо коробку надо было вешать на пояс. С другой стороны, держать в руках легкую пластмассовую трубку от бытового телефона было куда удобнее, нежели устройство с весом армейского пистолета (По признанию Мартина Купера, пользование мобильником помогло ему хорошо накачать мышцы).

По расчетам Куприяновича, его аппарат должен был стоить 300-400 советских рублей. Это было равно стоимости хорошего телевизора или легкого мотоцикла; при такой цене аппарат был бы доступен, конечно, не каждой советской семье, но накопить на него при желании смогли бы довольно многие. Коммерческие мобильники начала 80-х с ценой 3500-4000 долларов США тоже были не всем американцам по карману — миллионнный абонент появился лишь у 1990 году.

По утверждению Л.И.Куприяновича в его статье, опубликованной в февральском номере журнала «Техника-молодежи» за 1959 год, теперь на одной волне можно было разместить до тысячи каналов связи радиофонов с АТР. Для этого кодирование номера в радиофоне производилось импульсным способом, а при разговоре сигнал сжимался с помощью устройства, который автор радиофона назвал коррелятором. По описанию в той же статье, в основу работы коррелятора был положен принцип вокодера — разделение сигнала речи на несколько диапазонов частот, сжатие каждого диапазона и последующее восстановление в месте приема. Правда, узнаваемость голоса при этом должна была ухудшиться, но при качестве тогдашней проводной связи это не было серьезной проблемой. Куприянович предлагал устанавливать АТР на высотном здании в городе (сотрудники Мартина Купера пятнадцать лет спустя установили базовую станцию на вершине 50-этажного здания в Нью-Йорке). А судя по фразе «изготовленные автором этой статьи карманные радиофоны», можно сделать вывод, что в 1959 году Куприяновичем было изготовлено не менее двух опытных мобильников.

Аппарат 1958 года уже был больше похож на мобильники

«Пока имеются лишь опытные образцы нового аппарата, но можно не сомневаться, что он получит в скором времени большое распространение на транспорте, в городской телефонной сети, в промышленности, на стройках и т.д.» пишет Куприянович в журнале «Наука и жизнь» в августе 1957 года. Однако спустя три года в прессе вообще исчезают какие-либо публикации о дальнейшей судьбе разработки, грозящей сделать переворот в средствах связи. Причем сам изобретатель никуда не пропадает; например, в февральском номере «ЮТ» за 1960 г. он публикует описание радиостанции с автоматическим вызовом и дальностью действия 40-50 км, а в январском номере той же «Техники — молодежи» за 1961 год — популярную статью о технологиях микроэлектроники, в которой ни разу не упоминается о радиофоне.

Все это так странно и необычно, что невольно наталкивает на мысль: а был ли на самом деле работающий радиофон?

Скептики прежде всего обращают внимание на тот факт, что в публикациях, которые научно-популярные издания посвятили радиофону, не был освещен сенсационный факт первых телефонных звонков. Из фотографий тоже нельзя точно определить, то ли изобретатель звонит по мобильнику, то ли просто позирует. Отсюда возникает версия: да, попытка создания мобильника была, но технически аппарат не удалось довести, поэтому о нем больше и не писали. Однако задумаемся над вопросом: а с какой стати журналисты 50-х должны считать звонок отдельным событием, достойным упоминания в прессе? «Так это значит, телефон? Неплохо, неплохо. А по нему, оказывается, еще и звонить можно? Это просто чудо! Никогда бы не поверил!»

Здравый смысл подсказывает, что про неработающую конструкцию в 1957-1959 г. ни один советский научно-популярный журнал писать бы не стал. Таким журналам и без того было о чем писать. В космосе летают спутники. Физики установили, что каскадный гиперон распадается на лямбда-нуль-частицу и отрицательный пи-мезон. Звукотехники восстановили первоначальное звучание голоса Ленина. Добраться от Москвы до Хабаровска благодаря ТУ-104 можно за 11 часов 35 минут. Компьютеры переводят с одного языка на другой и играют в шахматы. Начато строительство Братской ГЭС. Школьники со станции «Чкаловская» сделали робота, который видит и говорит. На фоне этих событий создание мобильного телефона — это вообще не сенсация. Читатели ждут видеотелефонов! «Телефонные аппараты с экранами можно строить хоть сегодня, наша техника достаточно сильна» — пишут они в том же «ТМ» … в 1956 году. «Миллионы телезрителей ждут, когда же радиотехническая промышленность приступит к выпуску телевизоров с цветным изображением.. Давно пора подумать о телевизионной трансляции по проводам (кабельном ТВ — О.И.)»- читаем в том же номере. А тут, понимаете, мобила какая-то несовременная, даже без видеокамеры и цветного дисплея. Ну кто о ней бы написал хоть полслова, если бы она не работала?

Тогда почему же «первый звонок» стали считать сенсацией? Ответ простой: так захотел Мартин Купер. 3 апреля 1973 года им была проведена пиар-акция. Чтобы компания Motorola смогла получить разрешение на использование радиочастот для гражданской мобильной связи у Федеральной Комиссия по Коммуникациям (Federal Communications Commissions или FСС), необходимо было как-то показать, что мобильная связь действительно имеет будущее. Тем более, что на те же частоты претендовали конкуренты. И не случайно первый звонок Мартина Купера, по его собственному рассказу журналистам San Francisco Chronicle , был адресован сопернику: «Это был один парень из AT&T, продвигавший телефоны для автомобилей. Его звали Джоэл Энджел. Я позвонил ему, и рассказал, что звоню с улицы, с настоящего «ручного» сотового телефона. Я не помню, что он ответил. Но вы знаете, я слышал, как скрипят его зубы».

Куприяновичу не требовалось в 1957 — 1959 годах делить частоты с конкурирующей фирмой и выслушивать по мобильнику их скрежет зубовный. Ему не требовалось даже догонять и перегонять Америку, ввиду отсутствия других участников забега. Как и Купер, Куприянович тоже проводил пиар-акции — так, как это было принято в СССР. Он приходил в редакции научно-популярных изданий, демонстрировал аппараты, сам писал статьи о них. Вполне вероятно, что буквы «ЮТ» в названии первого аппарата — прием, чтобы заинтересовать редакцию «Юного техника» разместить его публикацию. По непонятным обстоятельствам тему радиофона обошел только ведущий радиолюбительский журнал страны — «Радио», как, впрочем, и все другие конструкции Куприяновича — кроме карманной рации 1955 года.

Были ли у самого Куприяновича мотивы показывать неработающий аппарат — например, чтобы добиться успеха или признания? В публикациях 50-х годов место работы изобретателя не указывается, СМИ представляют его читателям как «радиолюбителя» или «инженера». Однако известно, что Леонид Иванович жил и работал в Москве, ему было присвоена ученая степень кандидата технических наук, впоследствии он работал в Академии медицинских наук СССР и в начале 60-х имел машину (для которой, кстати, сам создал радиотелефон и противоугонную радиосигнализацию). Иными словами, по советским меркам был человекам успешным. Сомневающиеся могут также проверить пару десятков опубликованных любительских конструкций, включая и адаптированный для юных техников ЛК-1. Из всего этого следует, что мобильник 1958 года был построен и работал.

Алтай-1″ в конце 50-х выглядел более реальным проектом, чем карманные мобильники

В отличие от радиофона Куприяновича, «Алтай» имел конкретных заказчиков, от которых зависело выделение средств. Кроме того, основная проблема при реализации обоих проектов была вовсе не в том, чтобы создать портативный аппарат, а в необходимости значительных вложений и времени в создание инфраструктуры связи и ее отладку и расходов на ее содержание. При развертывании «Алтая», например, в Киеве выходили из строя выходные лампы передатчиков, в Ташкенте возникали проблемы из-за некачественного монтажа оборудования базовых станций. Как писал журнал «Радио», в 1968 году систему «Алтай» удалось развернуть только в Москве и Киеве, на очереди были Самарканд, Ташкент, Донецк и Одесса.

В системе «Алтай» обеспечить покрытие местности было проще, т.к. абонент мог удаляться от центральной базовой станции на расстояние до 60 км, а за пределами города было достаточно линейных станций, размещенных вдоль дорог на 40-60 км. Восемь передатчиков обслуживали до 500-800 абонентов, а качество передачи было сопоставимо только с цифровой связью. Реализация этого проекта выглядела более реальной, чем развертывание национальной сотовой сети на базе «Радиофона».

Тем не менее, идею мобильника, несмотря на видимую несвоевременность, вовсе не похоронили. Были и промышленные образцы аппарата!

Западноевропейские страны также предпринимали попытки создания мобильной связи до «исторического звонка Купера». Так, 11 апреля 1972 года, т.е. на год раньше, британская фирма Pye Telecommunications продемонстрировала на выставке «Связь сегодня, завтра и в будущем» («Communications Today, Tomorrow and the Future») в лондонском отеле Royal Lancaster, портативный мобильный телефон по которому можно было звонить в гордскую телефонную сеть.

Мобильник состоял из рации Pocketphone 70, применявшейся в полиции, и приставки — трубки с кнопочным набором, которую можно было держать в руках. Телефон работал в диапазоне 450-470 Мгц, судя по данным рации Pocketphone 70, мог иметь до 12 каналов и питался от источника напряжением 15 В.

Также имеются сведения о существовании во Франции в 60-х годах созданного мобильного телефона с полуавтоматической коммутацией абонентов. Цифры набираемого номера отображались на декатронах на базовой станции, после чего телефонистка вручную осуществляла коммутацию. Точных данных, почему была принята такя странная система набора, на данный момент нет, можно лишь предположить, что возможной причтиной были ошибки при передаче номера, которые устраняла телефонистка.

Мобильный телефон британской фирмы Pye Telecommunications, 11 апреля 1972 г

Но вернемся к судьбе Куприяновича. В 60-х годах он отходит от создания радиостанций и переключается на новое направление, лежащее на стыке электроники и медицины — использование кибернетики для расширения возможности человеческого мозга. Он публикует популярные статьи по гипнопедии — методам обучения человека во сне, а в 1970 году в издательстве «Наука» выходит его книга «Резервы улучшения памяти. Кибернетические аспекты», в которой, в частности, рассматривает проблемы «записи» информации в подсознание во время специального «сна на информационном уровне». Для ввода человека в состояние такого сна Куприянович создает аппарат «Ритмосон», и выдвигает идею нового сервиса — массового обучения людей во сне по телефону, причем биотоки людей через центральный компьютер управляют аппаратами сна.

Но и эта идея Куприяновича остается нереализованной, а в вышедшей в 1973 году его книге «Биологические ритмы и сон» аппарат «Ритмосон» в основном позиционируется как прибор для коррекции нарушений сна. Причины, возможно, следует искать во фразе из «Резервов улучшения памяти»: «Задача улучшения памяти состоит в решении проблемы управления сознанием, а через него, в значительной степени, и подсознанием». Человеку в состоянии сна на информационном уровне в принципе можно записать в память не только иностранные слова для запоминания, но и рекламные слоганы, бэкграундную информацию, рассчитанную на бессознательное восприятие, причем человек не в состоянии это процесс контролировать, и даже может не помнить, был ли он в состоянии такого сна. Здесь возникает слишком много морально-этических проблем и нынешнее человеческое общество явно не готово к массовому применению таких технологий.

Другие пионеры мобильной связи также сменили тему работы.

Георгий Бабат еще к концу войны сосредоточился над другой своей идеей — транспорта с питанием за счет СВЧ-излучения, сделал более ста изобретений, стал доктором наук, был удостоен Сталинской премии, а также прославился как автор научно-фантастических произведений.

Алфред Гросс продолжил работу, как специалист по СВЧ-технике и связи для компаний Сперри и Дженерал Электрик. Он продолжал творить вплоть до своей смерти в возрасе 82 лет.

Христо Бачваров в 1967 году занялся системой радиосинхронизации городских часов, за что получил две золотые медали на Лейпцигской ярмарке, возглавлял институт радиолектроники, был награжден руководством страны за другие разработки. Позднее переключился на системы высокочастотного зажигания в автомобильных двигателях.

Мартин Купер возглавил маленькую частную фирму ArrayComm, продвигающей на рынок собственную технологию быстрого беспроводного Интернета.

Вместо эпилога. Через 30 лет после создания ЛК-1, 9 апреля 1987 года, в отеле «KALASTAJATORPPA» в Хельсинки (Финляндия) генеральный секретарь ЦК КПСС М.С.Горбачев совершил мобильный звонок в Министерство связи СССР в присутствии вице-президента Nokia Стефана Видомски. Так мобильный телефон превратился в средство влияния на умы политиков — так же как первый спутник во времена Хрущева. Хотя, в отличие от спутника, действующий мобильник на самом деле не был показателем технического превосходства — по нему имел возможность звонить тот же Хрущев…

«Постойте!» — возразит читатель. » Так кого же следует считать создателем первого мобильного телефона — Купера, Куприяновича, Бачварова?»

Думается, противопоставлять результаты работ здесь не имеет смысла. Экономические же возможности для массового использования нового сервиса сложились лишь к 1990 году.

Не исключено, что были и другие попытки создания носимого мобильника, опередившие свое время, и человечество когда-нибудь о них вспомнит.

источник Олег Измеров

П.С.: спасибо френду ihoraksjuta за интересную идею.

А из технических интересностей посоветовал бы вам вспомнить про ЛЕТЯЩИХ ПО РЕЛЬСАМ

Оригинал статьи находится на сайте ИнфоГлаз.рф Ссылка на статью, с которой сделана эта копия — http://infoglaz.ru/?p=13844

For the modern mobile phone, see Smartphone.

A mobile phone[a] is a portable telephone that can make and receive calls over a radio frequency link while the user is moving within a telephone service area. The radio frequency link establishes a connection to the switching systems of a mobile phone operator, which provides access to the public switched telephone network (PSTN). Modern mobile telephone services use a cellular network architecture and, therefore, mobile telephones are called cellular telephones or cell phones in North America. In addition to telephony, digital mobile phones (2G) support a variety of other services, such as text messaging, multimedia messagIng, email, Internet access, short-range wireless communications (infrared, Bluetooth), business applications, video games and digital photography. Mobile phones offering only those capabilities are known as feature phones; mobile phones which offer greatly advanced computing capabilities are referred to as smartphones.[1]

The first handheld mobile phone was demonstrated by Martin Cooper of Motorola in New York City in 1973, using a handset weighing c. 2 kilograms (4.4 lbs).[2] In 1979, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) launched the world’s first cellular network in Japan.[3] In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone. From 1983 to 2014, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew to over seven billion; enough to provide one for every person on Earth.[4] In the first quarter of 2016, the top smartphone developers worldwide were Samsung, Apple and Huawei; smartphone sales represented 78 percent of total mobile phone sales.[5] For feature phones (slang: «dumbphones») as of 2016, the top-selling brands were Samsung, Nokia and Alcatel.[6]

Mobile phones are considered an important human invention as it has been one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology.[7] The growth in popularity has been rapid in some places, for example in the UK the total number of mobile phones overtook the number of houses in 1999.[8] Today mobile phones are globally ubiquitous,[9] and in almost half the world’s countries, over 90% of the population own at least one.[10]

History

Martin Cooper of Motorola, shown here in a 2007 reenactment, made the first publicized handheld mobile phone call on a prototype DynaTAC model on 3 April 1973.

A handheld mobile radio telephone service was envisioned in the early stages of radio engineering. In 1917, Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt filed a patent for a «pocket-size folding telephone with a very thin carbon microphone». Early predecessors of cellular phones included analog radio communications from ships and trains. The race to create truly portable telephone devices began after World War II, with developments taking place in many countries. The advances in mobile telephony have been traced in successive «generations», starting with the early zeroth-generation (0G) services, such as Bell System’s Mobile Telephone Service and its successor, the Improved Mobile Telephone Service. These 0G systems were not cellular, supported few simultaneous calls, and were very expensive.

The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X. In 1983, it became the first commercially available handheld cellular mobile phone.

The first handheld cellular mobile phone was demonstrated by John F. Mitchell[11][12] and Martin Cooper of Motorola in 1973, using a handset weighing 2 kilograms (4.4 lb).[2] The first commercial automated cellular network (1G) analog was launched in Japan by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone in 1979. This was followed in 1981 by the simultaneous launch of the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[13] Several other countries then followed in the early to mid-1980s. These first-generation (1G) systems could support far more simultaneous calls but still used analog cellular technology. In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone.

In 1991, the second-generation (2G) digital cellular technology was launched in Finland by Radiolinja on the GSM standard. This sparked competition in the sector as the new operators challenged the incumbent 1G network operators. The GSM standard is a European initiative expressed at the CEPT («Conférence Européenne des Postes et Telecommunications», European Postal and Telecommunications conference). The Franco-German R&D cooperation demonstrated the technical feasibility, and in 1987 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between 13 European countries who agreed to launch a commercial service by 1991. The first version of the GSM (=2G) standard had 6,000 pages. The IEEE and RSE awarded to Thomas Haug and Philippe Dupuis the 2018 James Clerk Maxwell medal for their contributions to the first digital mobile telephone standard.[14] In 2018, the GSM was used by over 5 billion people in over 220 countries. The GSM (2G) has evolved into 3G, 4G and 5G. The standardisation body for GSM started at the CEPT Working Group GSM (Group Special Mobile) in 1982 under the umbrella of CEPT. In 1988, ETSI was established and all CEPT standardization activities were transferred to ETSI. Working Group GSM became Technical Committee GSM. In 1991, it became Technical Committee SMG (Special Mobile Group) when ETSI tasked the committee with UMTS (3G).

Dupuis and Haug during a GSM meeting in Belgium, April 1992

In 2001, the third generation (3G) was launched in Japan by NTT DoCoMo on the WCDMA standard.[15] This was followed by 3.5G, 3G+ or turbo 3G enhancements based on the high-speed packet access (HSPA) family, allowing UMTS networks to have higher data transfer speeds and capacity.

By 2009, it had become clear that, at some point, 3G networks would be overwhelmed by the growth of bandwidth-intensive applications, such as streaming media.[16] Consequently, the industry began looking to data-optimized fourth-generation technologies, with the promise of speed improvements up to ten-fold over existing 3G technologies. The first two commercially available technologies billed as 4G were the WiMAX standard, offered in North America by Sprint, and the LTE standard, first offered in Scandinavia by TeliaSonera.

5G is a technology and term used in research papers and projects to denote the next major phase in mobile telecommunication standards beyond the 4G/IMT-Advanced standards. The term 5G is not officially used in any specification or official document yet made public by telecommunication companies or standardization bodies such as 3GPP, WiMAX Forum or ITU-R. New standards beyond 4G are currently being developed by standardization bodies, but they are at this time seen as under the 4G umbrella, not for a new mobile generation.

Types

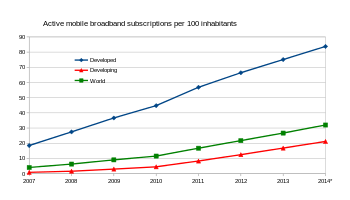

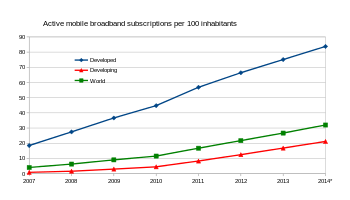

Active mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants.[17]

Smartphone

Smartphones have a number of distinguishing features. The International Telecommunication Union measures those with Internet connection, which it calls Active Mobile-Broadband subscriptions (which includes tablets, etc.). In the developed world, smartphones have now overtaken the usage of earlier mobile systems. However, in the developing world, they account for around 50% of mobile telephony.

Feature phone

Feature phone is a term typically used as a retronym to describe mobile phones which are limited in capabilities in contrast to a modern smartphone. Feature phones typically provide voice calling and text messaging functionality, in addition to basic multimedia and Internet capabilities, and other services offered by the user’s wireless service provider. A feature phone has additional functions over and above a basic mobile phone, which is only capable of voice calling and text messaging.[18][19] Feature phones and basic mobile phones tend to use a proprietary, custom-designed software and user interface. By contrast, smartphones generally use a mobile operating system that often shares common traits across devices.

Infrastructure

Cellular networks work by only reusing radio frequencies (in this example frequencies f1-f4) in non adjacent cells to avoid interference

Mobile phones communicate with cell towers that are placed to give coverage across a telephone service area, which is divided up into ‘cells’. Each cell uses a different set of frequencies from neighboring cells, and will typically be covered by three towers placed at different locations. The cell towers are usually interconnected to each other and the phone network and the internet by wired connections. Due to bandwidth limitations each cell will have a maximum number of cell phones it can handle at once. The cells are therefore sized depending on the expected usage density, and may be much smaller in cities. In that case much lower transmitter powers are used to avoid broadcasting beyond the cell.

In order to handle the high traffic, multiple towers can be set up in the same area (using different frequencies). This can be done permanently or temporarily such as at special events like at the Super Bowl, Taste of Chicago, State Fair, NYC New Year’s Eve, hurricane hit cities, etc. where cell phone companies will bring a truck with equipment to host the abnormally high traffic with a portable cell.

Cellular can greatly increase the capacity of simultaneous wireless phone calls. While a phone company for example, has a license to 1,000 frequencies, each cell must use unique frequencies with each call using one of them when communicating. Because cells only slightly overlap, the same frequency can be reused. Example cell one uses frequency 1–500, next door cell uses frequency 501–1,000, next door can reuse frequency 1–500. Cells one and three are not «touching» and do not overlap/communicate so each can reuse the same frequencies.[citation needed]

Capacity was further increased when phone companies implemented digital networks. With digital, one frequency can host multiple simultaneous calls.

As a phone moves around, a phone will «hand off» — automatically disconnect and reconnect to the tower of another cell that gives the best reception.

Additionally, short-range Wi-Fi infrastructure is often used by smartphones as much as possible as it offloads traffic from cell networks on to local area networks.

Hardware

The common components found on all mobile phones are:

- A central processing unit (CPU), the processor of phones. The CPU is a microprocessor fabricated on a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chip.

- A battery, providing the power source for the phone functions. A modern handset typically uses a lithium-ion battery (LIB), whereas older handsets used nickel–metal hydride (Ni–MH) batteries.

- An input mechanism to allow the user to interact with the phone. These are a keypad for feature phones, and touch screens for most smartphones (typically with capacitive sensing).

- A display which echoes the user’s typing, and displays text messages, contacts, and more. The display is typically either a liquid-crystal display (LCD) or organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display.

- Speakers for sound.

- Subscriber identity module (SIM) cards and removable user identity module (R-UIM) cards.

- A hardware notification LED on some phones

Low-end mobile phones are often referred to as feature phones and offer basic telephony. Handsets with more advanced computing ability through the use of native software applications are known as smartphones.

Central processing unit

Mobile phones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments.

Mobile CPU performance depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[20] but also the memory hierarchy also greatly affects overall performance. Because of these problems, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Display

One of the main characteristics of phones is the screen. Depending on the device’s type and design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device’s front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017.

Screen sizes are often measured in diagonal inches or millimeters; feature phones generally have screen sizes below 90 millimetres (3.5 in). Phones with screens larger than 130 millimetres (5.2 in) are often called «phablets.» Smartphones with screens over 115 millimetres (4.5 in) in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and «edge-to-edge» designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[21][22][23]

Liquid-crystal displays are the most common; others are IPS, LED, OLED, and AMOLED displays. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[24] and Apple’s «3D Touch» system.

Sound

In sound, smartphones and feature phones vary little. Some audio-quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice, have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[25][26] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over WiFi.[27] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear.

Battery

The average phone battery lasts 2–3 years at best. Many of the wireless devices use a Lithium-Ion (Li-Ion) battery, which charges 500–2500 times, depending on how users take care of the battery and the charging techniques used.[28] It is only natural for these rechargeable batteries to chemically age, which is why the performance of the battery when used for a year or two will begin to deteriorate. Battery life can be extended by draining it regularly, not overcharging it, and keeping it away from heat.[29][30]

SIM card

Mobile phones require a small microchip called a Subscriber Identity Module or SIM card, in order to function. The SIM card is approximately the size of a small postage stamp and is usually placed underneath the battery in the rear of the unit. The SIM securely stores the service-subscriber key (IMSI) and the Ki used to identify and authenticate the user of the mobile phone. The SIM card allows users to change phones by simply removing the SIM card from one mobile phone and inserting it into another mobile phone or broadband telephony device, provided that this is not prevented by a SIM lock. The first SIM card was made in 1991 by Munich smart card maker Giesecke & Devrient for the Finnish wireless network operator Radiolinja.[citation needed]

A hybrid mobile phone can hold up to four SIM cards, with a phone having a different device identifier for each SIM Card. SIM and R-UIM cards may be mixed together to allow both GSM and CDMA networks to be accessed. From 2010 onwards, such phones became popular in emerging markets,[31] and this was attributed to the desire to obtain the lowest calling costs.

When the removal of a SIM card is detected by the operating system, it may deny further operation until a reboot.[32]

Software

Software platforms

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2018) |

Feature phones have basic software platforms. Smartphones have advanced software platforms. Android OS has been the best-selling OS worldwide on smartphones since 2011.

Mobile app

A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term «app» is a shortening of the term «software application».

- Messaging

A common data application on mobile phones is Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging. The first SMS message was sent from a computer to a mobile phone in 1992 in the UK while the first person-to-person SMS from phone to phone was sent in Finland in 1993. The first mobile news service, delivered via SMS, was launched in Finland in 2000,[33] and subsequently many organizations provided «on-demand» and «instant» news services by SMS. Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) was introduced in March 2002.[34]

Application stores

The introduction of Apple’s App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google’s Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store), RIM’s BlackBerry App World, or Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[35]

Sales

By manufacturer

| Rank | Manufacturer | Strategy Analytics report[36] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung | 21% |

| 2 | Apple | 16% |

| 3 | Xiaomi | 13% |

| 4 | Oppo | 10% |

| 5 | Vivo | 9% |

| Others | 31% | |

| Note: Vendor shipments are branded shipments and exclude OEM sales for all vendors. |

As of 2022, the top five manufacturers worldwide were Samsung (21%), Apple (16%), Xiaomi (13%), Oppo (10%), and Vivo (9%).[37]

- History

From 1983 to 1998, Motorola was market leader in mobile phones. Nokia was the market leader in mobile phones from 1998 to 2012.[38] In Q1 2012, Samsung surpassed Nokia, selling 93.5 million units as against Nokia’s 82.7 million units. Samsung has retained its top position since then.

Aside from Motorola, European brands such as Nokia, Siemens and Ericsson once held large sway over the global mobile phone market, and many new technologies were pioneered in Europe. By 2010, the influence of European companies had significantly decreased due to fierce competition from American and Asian companies, to where most technical innovation had shifted.[39][40] Apple and Google, both of the United States, also came to dominate mobile phone software.[39]

By mobile phone operator

The world’s largest individual mobile operator by number of subscribers is China Mobile, which has over 902 million mobile phone subscribers as of June 2018.[41] Over 50 mobile operators have over ten million subscribers each, and over 150 mobile operators had at least one million subscribers by the end of 2009.[42] In 2014, there were more than seven billion mobile phone subscribers worldwide, a number that is expected to keep growing.

Use

Mobile phone subscribers per 100 inhabitants. 2014 figure is estimated.

Mobile phones are used for a variety of purposes, such as keeping in touch with family members, for conducting business, and in order to have access to a telephone in the event of an emergency. Some people carry more than one mobile phone for different purposes, such as for business and personal use. Multiple SIM cards may be used to take advantage of the benefits of different calling plans. For example, a particular plan might provide for cheaper local calls, long-distance calls, international calls, or roaming.

The mobile phone has been used in a variety of diverse contexts in society. For example:

- A study by Motorola found that one in ten mobile phone subscribers have a second phone that is often kept secret from other family members. These phones may be used to engage in such activities as extramarital affairs or clandestine business dealings.[43]

- Some organizations assist victims of domestic violence by providing mobile phones for use in emergencies. These are often refurbished phones.[44]

- The advent of widespread text-messaging has resulted in the cell phone novel, the first literary genre to emerge from the cellular age, via text messaging to a website that collects the novels as a whole.[45]

- Mobile telephony also facilitates activism and citizen journalism.

- The United Nations reported that mobile phones have spread faster than any other form of technology and can improve the livelihood of the poorest people in developing countries, by providing access to information in places where landlines or the Internet are not available, especially in the least developed countries. Use of mobile phones also spawns a wealth of micro-enterprises, by providing such work as selling airtime on the streets and repairing or refurbishing handsets.[46]

- In Mali and other African countries, people used to travel from village to village to let friends and relatives know about weddings, births, and other events. This can now be avoided in areas with mobile phone coverage, which are usually more extensive than areas with just land-line penetration.

- The TV industry has recently started using mobile phones to drive live TV viewing through mobile apps, advertising, social TV, and mobile TV.[47] It is estimated that 86% of Americans use their mobile phone while watching TV.

- In some parts of the world, mobile phone sharing is common. Cell phone sharing is prevalent in urban India, as families and groups of friends often share one or more mobile phones among their members. There are obvious economic benefits, but often familial customs and traditional gender roles play a part.[48] It is common for a village to have access to only one mobile phone, perhaps owned by a teacher or missionary, which is available to all members of the village for necessary calls.[49]

Content distribution

In 1998, one of the first examples of distributing and selling media content through the mobile phone was the sale of ringtones by Radiolinja in Finland. Soon afterwards, other media content appeared, such as news, video games, jokes, horoscopes, TV content and advertising. Most early content for mobile phones tended to be copies of legacy media, such as banner advertisements or TV news highlight video clips. Recently, unique content for mobile phones has been emerging, from ringtones and ringback tones to mobisodes, video content that has been produced exclusively for mobile phones.[citation needed]

Mobile banking and payment

In many countries, mobile phones are used to provide mobile banking services, which may include the ability to transfer cash payments by secure SMS text message. Kenya’s M-PESA mobile banking service, for example, allows customers of the mobile phone operator Safaricom to hold cash balances which are recorded on their SIM cards. Cash can be deposited or withdrawn from M-PESA accounts at Safaricom retail outlets located throughout the country and can be transferred electronically from person to person and used to pay bills to companies.

Branchless banking has also been successful in South Africa and the Philippines. A pilot project in Bali was launched in 2011 by the International Finance Corporation and an Indonesian bank, Bank Mandiri.[50]

Mobile payments were first trialled in Finland in 1998 when two Coca-Cola vending machines in Espoo were enabled to work with SMS payments. Eventually, the idea spread and in 1999, the Philippines launched the country’s first commercial mobile payments systems with mobile operators Globe and Smart.[citation needed]

Some mobile phones can make mobile payments via direct mobile billing schemes, or through contactless payments if the phone and the point of sale support near field communication (NFC).[51] Enabling contactless payments through NFC-equipped mobile phones requires the co-operation of manufacturers, network operators, and retail merchants.[52][53]

Mobile tracking

Mobile phones are commonly used to collect location data. While the phone is turned on, the geographical location of a mobile phone can be determined easily (whether it is being used or not) using a technique known as multilateration to calculate the differences in time for a signal to travel from the mobile phone to each of several cell towers near the owner of the phone.[54][55]

The movements of a mobile phone user can be tracked by their service provider and, if desired, by law enforcement agencies and their governments. Both the SIM card and the handset can be tracked.[54]

China has proposed using this technology to track the commuting patterns of Beijing city residents.[56] In the UK and US, law enforcement and intelligence services use mobile phones to perform surveillance operations.[57]

Hackers have been able to track a phone’s location, read messages, and record calls, through obtaining a subscribers phone number.[58]

While driving

A driver using two handheld mobile phones at once

A sign in the U.S. restricting cell phone use to certain times of day (no cell phone use between 7:30am-9:00am and 2:00pm-4:15pm)

Mobile phone use while driving, including talking on the phone, texting, or operating other phone features, is common but controversial. It is widely considered dangerous due to distracted driving. Being distracted while operating a motor vehicle has been shown to increase the risk of accidents. In September 2010, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that 995 people were killed by drivers distracted by cell phones. In March 2011, a U.S. insurance company, State Farm Insurance, announced the results of a study which showed 19% of drivers surveyed accessed the Internet on a smartphone while driving.[59] Many jurisdictions prohibit the use of mobile phones while driving. In Egypt, Israel, Japan, Portugal, and Singapore, both handheld and hands-free use of a mobile phone (which uses a speakerphone) is banned. In other countries, including the UK and France and in many U.S. states, only handheld phone use is banned while hands-free use is permitted.

A 2011 study reported that over 90% of college students surveyed text (initiate, reply or read) while driving.[60]

The scientific literature on the dangers of driving while sending a text message from a mobile phone, or texting while driving, is limited. A simulation study at the University of Utah found a sixfold increase in distraction-related accidents when texting.[61]

Due to the increasing complexity of mobile phones, they are often more like mobile computers in their available uses. This has introduced additional difficulties for law enforcement officials when attempting to distinguish one usage from another in drivers using their devices. This is more apparent in countries which ban both handheld and hands-free usage, rather than those which ban handheld use only, as officials cannot easily tell which function of the mobile phone is being used simply by looking at the driver. This can lead to drivers being stopped for using their device illegally for a phone call when, in fact, they were using the device legally, for example, when using the phone’s incorporated controls for car stereo, GPS or satnav.

A 2010 study reviewed the incidence of mobile phone use while cycling and its effects on behaviour and safety.[62] In 2013, a national survey in the US reported the number of drivers who reported using their cellphones to access the Internet while driving had risen to nearly one of four.[63] A study conducted by the University of Vienna examined approaches for reducing inappropriate and problematic use of mobile phones, such as using mobile phones while driving.[64]

Accidents involving a driver being distracted by talking on a mobile phone have begun to be prosecuted as negligence similar to speeding. In the United Kingdom, from 27 February 2007, motorists who are caught using a hand-held mobile phone while driving will have three penalty points added to their license in addition to the fine of £60.[65] This increase was introduced to try to stem the increase in drivers ignoring the law.[66] Japan prohibits all mobile phone use while driving, including use of hands-free devices. New Zealand has banned hand-held cell phone use since 1 November 2009. Many states in the United States have banned texting on cell phones while driving. Illinois became the 17th American state to enforce this law.[67] As of July 2010, 30 states had banned texting while driving, with Kentucky becoming the most recent addition on 15 July.[68]

Public Health Law Research maintains a list of distracted driving laws in the United States. This database of laws provides a comprehensive view of the provisions of laws that restrict the use of mobile communication devices while driving for all 50 states and the District of Columbia between 1992 when first law was passed, through 1 December 2010. The dataset contains information on 22 dichotomous, continuous or categorical variables including, for example, activities regulated (e.g., texting versus talking, hands-free versus handheld), targeted populations, and exemptions.[69]

In 2010, an estimated 1500 pedestrians were injured in the US while using a cellphone and some jurisdictions have attempted to ban pedestrians from using their cellphones.[70][71]

Health effects

The effect of mobile phone radiation on human health is the subject of recent[when?] interest and study, as a result of the enormous increase in mobile phone usage throughout the world. Mobile phones use electromagnetic radiation in the microwave range, which some believe may be harmful to human health. A large body of research exists, both epidemiological and experimental, in non-human animals and in humans. The majority of this research shows no definite causative relationship between exposure to mobile phones and harmful biological effects in humans. This is often paraphrased simply as the balance of evidence showing no harm to humans from mobile phones, although a significant number of individual studies do suggest such a relationship, or are inconclusive. Other digital wireless systems, such as data communication networks, produce similar radiation.[citation needed]

On 31 May 2011, the World Health Organization stated that mobile phone use may possibly represent a long-term health risk,[72][73] classifying mobile phone radiation as «possibly carcinogenic to humans» after a team of scientists reviewed studies on mobile phone safety.[74] The mobile phone is in category 2B, which ranks it alongside coffee and other possibly carcinogenic substances.[75][76]

Some recent[when?] studies have found an association between mobile phone use and certain kinds of brain and salivary gland tumors. Lennart Hardell and other authors of a 2009 meta-analysis of 11 studies from peer-reviewed journals concluded that cell phone usage for at least ten years «approximately doubles the risk of being diagnosed with a brain tumor on the same (‘ipsilateral’) side of the head as that preferred for cell phone use».[77]

One study of past mobile phone use cited in the report showed a «40% increased risk for gliomas (brain cancer) in the highest category of heavy users (reported average: 30 minutes per day over a 10‐year period)».[78] This is a reversal of the study’s prior position that cancer was unlikely to be caused by cellular phones or their base stations and that reviews had found no convincing evidence for other health effects.[73][79] However, a study published 24 March 2012, in the British Medical Journal questioned these estimates because the increase in brain cancers has not paralleled the increase in mobile phone use.[80] Certain countries, including France, have warned against the use of mobile phones by minors in particular, due to health risk uncertainties.[81] Mobile pollution by transmitting electromagnetic waves can be decreased up to 90% by adopting the circuit as designed in mobile phone and mobile exchange.[82]

In May 2016, preliminary findings of a long-term study by the U.S. government suggested that radio-frequency (RF) radiation, the type emitted by cell phones, can cause cancer.[83][84]

Educational impact

A study by the London School of Economics found that banning mobile phones in schools could increase pupils’ academic performance, providing benefits equal to one extra week of schooling per year.[85]

Electronic waste regulation

Studies have shown that around 40–50% of the environmental impact of mobile phones occurs during the manufacture of their printed wiring boards and integrated circuits.[86]

The average user replaces their mobile phone every 11 to 18 months,[87] and the discarded phones then contribute to electronic waste. Mobile phone manufacturers within Europe are subject to the WEEE directive, and Australia has introduced a mobile phone recycling scheme.[88]

Apple Inc. had an advanced robotic disassembler and sorter called Liam specifically for recycling outdated or broken iPhones.[89]

Theft

According to the Federal Communications Commission, one out of three robberies involve the theft of a cellular phone.[citation needed] Police data in San Francisco show that half of all robberies in 2012 were thefts of cellular phones.[citation needed] An online petition on Change.org, called Secure our Smartphones, urged smartphone manufacturers to install kill switches in their devices to make them unusable if stolen. The petition is part of a joint effort by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón and was directed to the CEOs of the major smartphone manufacturers and telecommunication carriers.[90] On 10 June 2013, Apple announced that it would install a «kill switch» on its next iPhone operating system, due to debut in October 2013.[91]

All mobile phones have a unique identifier called IMEI. Anyone can report their phone as lost or stolen with their Telecom Carrier, and the IMEI would be blacklisted with a central registry.[92] Telecom carriers, depending upon local regulation can or must implement blocking of blacklisted phones in their network. There are, however, a number of ways to circumvent a blacklist. One method is to send the phone to a country where the telecom carriers are not required to implement the blacklisting and sell it there,[93] another involves altering the phone’s IMEI number.[94] Even so, mobile phones typically have less value on the second-hand market if the phones original IMEI is blacklisted.

Conflict minerals

Demand for metals used in mobile phones and other electronics fuelled the Second Congo War, which claimed almost 5.5 million lives.[95] In a 2012 news story, The Guardian reported: «In unsafe mines deep underground in eastern Congo, children are working to extract minerals essential for the electronics industry. The profits from the minerals finance the bloodiest conflict since the second world war; the war has lasted nearly 20 years and has recently flared up again. For the last 15 years, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been a major source of natural resources for the mobile phone industry.»[96] The company Fairphone has worked to develop a mobile phone that does not contain conflict minerals.[citation needed]

Kosher phones

Due to concerns by the Orthodox Jewish rabbinate in Britain that texting by youths could waste time and lead to «immodest» communication, the rabbinate recommended that phones with text-messaging capability not be used by children; to address this, they gave their official approval to a brand of «Kosher» phones with no texting capabilities. Although these phones are intended to prevent immodesty, some vendors report good sales to adults who prefer the simplicity of the devices; other Orthodox Jews question the need for them.[97]

In Israel, similar phones to kosher phones with restricted features exist to observe the sabbath; under Orthodox Judaism, the use of any electrical device is generally prohibited during this time, other than to save lives, or reduce the risk of death or similar needs. Such phones are approved for use by essential workers, such as health, security, and public service workers.[98]

See also

- Cellular frequencies

- Customer proprietary network information

- Field telephone

- List of countries by number of mobile phones in use

- Mobile broadband

- Mobile Internet device (MID)

- Mobile phone accessories

- Mobile phones on aircraft

- Mobile phone use in schools

- Mobile technology

- Mobile telephony

- Mobile phone form factor

- Optical head-mounted display

- OpenBTS

- Pager

- Personal digital assistant

- Personal Handy-phone System

- Prepaid mobile phone

- Two-way radio

- Professional mobile radio

- Push-button telephone

- Rechargeable battery

- Smombie

- Surveillance

- Tethering

- VoIP phone

Notes

- ^ Also named cellular phone, cell phone, cellphone, handphone, hand phone or pocket phone, sometimes shortened to simply mobile, cell, or just phone.

References

- ^ Srivastava, Viranjay M.; Singh, Ghanshyam (2013). MOSFET Technologies for Double-Pole Four-Throw Radio-Frequency Switch. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9783319011653.

- ^ a b Teixeira, Tania (23 April 2010). «Meet the man who invented the mobile phone». BBC News. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ «Timeline from 1G to 5G: A Brief History on Cell Phones». CENGN. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ «Mobile penetration». 9 July 2010.

Almost 40 percent of the world’s population, 2.7 billion people, are online. The developing world is home to about 826 million female internet users and 980 million male internet users. The developed world is home to about 475 million female Internet users and 483 million male Internet users.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 3.9 Percent in First Quarter of 2016». Gartner. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ «Nokia Captured 9% Feature Phone Marketshare Worldwide in 2016». Strategyanalytics.com. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Harris, Arlene; Cooper, Martin (2019). «Mobile phones: Impacts, challenges, and predictions». Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 1: 15–17. doi:10.1002/hbe2.112. S2CID 187189041.

- ^ «BBC News | BUSINESS | Mobile phone sales surge».

- ^ Gupta, Gireesh K. (2011). «Ubiquitous mobile phones are becoming indispensable». ACM Inroads. 2 (2): 32–33. doi:10.1145/1963533.1963545. S2CID 2942617.

- ^ «Mobile phones are becoming ubiquitous». International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 17 February 2022.

- ^ «John F. Mitchell Biography». Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ «Who invented the cell phone?». Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ «Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology». Tekniskamuseet.se. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ «Duke of Cambridge Presents Maxwell Medals to GSM Developers». IEEE United Kingdom and Ireland Section. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ «History of UMTS and 3G Development». Umtsworld.com. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Fahd Ahmad Saeed. «Capacity Limit Problem in 3G Networks». Purdue School of Engineering. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ «Statistics». ITU.

- ^ «feature phone Definition from PC Magazine Encyclopedia». www.pcmag.com.

- ^ Todd Hixon, Two Weeks With A Dumb Phone Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, 13 November 2012

- ^ «CPU Frequency». CPU World Glossary. CPU World. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ «Don’t call it a phablet: the 5.5″ Samsung Galaxy S7 Edge is narrower than many 5.2″ devices». PhoneArena. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ «We’re gonna need Pythagoras’ help to compare screen sizes in 2017». The Verge. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ «The Samsung Galaxy S8 will change the way we think about display sizes». The Verge. Vox Media. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Ward, J. R.; Phillips, M. J. (1 April 1987). «Digitizer Technology: Performance Characteristics and the Effects on the User Interface». IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 7 (4): 31–44. doi:10.1109/MCG.1987.276869. ISSN 0272-1716. S2CID 16707568.

- ^ Jeff Hecht (30 September 2014). «Why Mobile Voice Quality Still Stinks—and How to Fix It». ieee.org.

- ^ Elena Malykhina. «Why Is Cell Phone Call Quality So Terrible?». scientificamerican.com.

- ^ Alan Henry (22 May 2014). «What’s the Best Mobile VoIP App?». Lifehacker. Gawker Media.

- ^ Taylor, Martin. «How To Prolong Your Cell Phone Battery’s Life Span». Phonedog.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ «Iphone Battery and Performance». Apple Support. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Hill, Simon. «Should You Leave Your Smartphone Plugged Into The Charger Overnight? We Asked An Expert». Digital Trends. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ «Smartphone boom lifts phone market in first quarter». Reuters. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ «How to Fix ‘No SIM Card Detected’ Error on Android». Make Tech Easier. 20 September 2020.

- ^ Lynn, Natalie (10 March 2016). «The History and Evolution of Mobile Advertising». Gimbal. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Bodic, Gwenaël Le (8 July 2005). Mobile Messaging Technologies and Services: SMS, EMS and MMS. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-01451-6.

- ^ W3C Interview: Vision Mobile on the App Developer Economy with Matos Kapetanakis and Dimitris Michalakos Archived 29 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ «Global Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter». Counterpoint Research. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ «Global Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter». Counterpoint Research. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Roger. «Farewell Nokia: The rise and fall of a mobile pioneer». CNET.

- ^ a b «How the smartphone made Europe look stupid». the Guardian. 14 February 2010.

- ^ Mobility, Yomi Adegboye AKA Mister (5 February 2020). «Non-Chinese smartphones: These phones are not made in China — MobilityArena.com». mobilityarena.com.

- ^ «Operation Data». China Mobile. 31 August 2017.

- ^ Source: wireless intelligence

- ^ «Millions keep secret mobile». BBC News. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Brooks, Richard (13 August 2007). «Donated cell phones help battered women». The Press-Enterprise. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (7 January 2009). «Letter from Japan: I ♥ Novels». The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Lynn, Jonathan. «Mobile phones help lift poor out of poverty: U.N. study». Reuters. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ «4 Ways Smartphones Can Save Live TV». Tvgenius.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Donner, Jonathan, and Steenson, Molly Wright. «Beyond the Personal and Private: Modes of Mobile Phone Sharing in Urban India.» In The Reconstruction of Space and Time: Mobile Communication Practices, edited by Scott Campbell and Rich Ling, 231–50. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2008.

- ^ Hahn, Hans; Kibora, Ludovic (2008). «The Domestication of the Mobile Phone: Oral Society and New ICT in Burkina Faso». Journal of Modern African Studies. 46: 87–109. doi:10.1017/s0022278x07003084. S2CID 154804246.

- ^ «Branchless banking to start in Bali». The Jakarta Post. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Feig, Nancy (25 June 2007). «Mobile Payments: Look to Korea». banktech.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Ready, Sarah (10 November 2009). «NFC mobile phone set to explode». connectedplanetonline.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Tofel, Kevin C. (20 August 2010). «VISA Testing NFC Memory Cards for Wireless Payments». gigaom.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ a b «Tracking a suspect by mobile phone». BBC News. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Miller, Joshua (14 March 2009). «Cell Phone Tracking Can Locate Terrorists — But Only Where It’s Legal». FOX News. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Cecilia Kang (3 March 2011). «China plans to track cellphone users, sparking human rights concerns». The Washington Post.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan; Anne Broache (1 December 2006). «FBI taps cell phone mic as eavesdropping tool». CNet News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (18 April 2016). «Your phone number is all a hacker needs to read texts, listen to calls and track you» – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ «Quit Googling yourself and drive: About 20% of drivers using Web behind the wheel, study says». Los Angeles Times. 4 March 2011.

- ^ Atchley, Paul; Atwood, Stephanie; Boulton, Aaron (January 2011). «The Choice to Text and Drive in Younger Drivers: Behaviour May Shape Attitude». Accident Analysis and Prevention. 43 (1): 134–142. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.08.003. PMID 21094307.

- ^ «Text messaging not illegal but data clear on its peril». Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

- ^ de Waard, D., Schepers, P., Ormel, W. and Brookhuis, K., 2010, Mobile phone use while cycling: Incidence and effects on behaviour and safety, Ergonomics, Vol 53, No. 1, January 2010, pp. 30–42.

- ^ «Drivers still Web surfing while driving, survey finds». USA TODAY.