This article is about the American basketball player. For other people with the same name, see Michael Jordan (disambiguation).

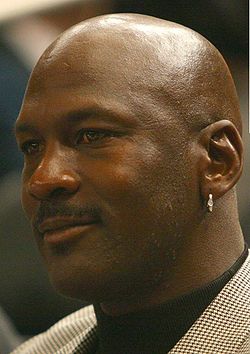

Jordan in 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Charlotte Hornets | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Owner | |||||||||||||||||

| League | NBA | |||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||

| Born | February 17, 1963 (age 59) New York City, New York, U.S. | |||||||||||||||||

| Listed height | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) | |||||||||||||||||

| Listed weight | 216 lb (98 kg)[a] | |||||||||||||||||

| Career information | ||||||||||||||||||

| High school | Emsley A. Laney (Wilmington, North Carolina) | |||||||||||||||||

| College | North Carolina (1981–1984) | |||||||||||||||||

| NBA draft | 1984 / Round: 1 / Pick: 3rd overall | |||||||||||||||||

| Selected by the Chicago Bulls | ||||||||||||||||||

| Playing career | 1984–1993, 1995–1998, 2001–2003 | |||||||||||||||||

| Position | Shooting guard | |||||||||||||||||

| Number | 23, 12,[b] 45 | |||||||||||||||||

| Career history | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1984–1993, 1995–1998 | Chicago Bulls | |||||||||||||||||

| 2001–2003 | Washington Wizards | |||||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Career NBA statistics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Points | 32,292 (30.1 ppg) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rebounds | 6,672 (6.2 rpg) | |||||||||||||||||

| Assists | 5,633 (5.3 apg) | |||||||||||||||||

| Stats | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | ||||||||||||||||||

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | ||||||||||||||||||

| FIBA Hall of Fame as player | ||||||||||||||||||

| Medals

|

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17, 1963), also known by his initials MJ,[9] is an American businessman and former professional basketball player. His biography on the official NBA website states: «By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the greatest basketball player of all time.»[10] He played fifteen seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA), winning six NBA championships with the Chicago Bulls. Jordan is the principal owner and chairman of the Charlotte Hornets of the NBA and of 23XI Racing in the NASCAR Cup Series. He was integral in popularizing the NBA around the world in the 1980s and 1990s,[11] becoming a global cultural icon in the process.[12]

Jordan played college basketball for three seasons under coach Dean Smith with the North Carolina Tar Heels. As a freshman, he was a member of the Tar Heels’ national championship team in 1982.[5] Jordan joined the Bulls in 1984 as the third overall draft pick,[5][13] and quickly emerged as a league star, entertaining crowds with his prolific scoring while gaining a reputation as one of the game’s best defensive players.[14] His leaping ability, demonstrated by performing slam dunks from the free-throw line in Slam Dunk Contests, earned him the nicknames «Air Jordan» and «His Airness«.[5][13] Jordan won his first NBA title with the Bulls in 1991, and followed that achievement with titles in 1992 and 1993, securing a three-peat. Jordan abruptly retired from basketball before the 1993–94 NBA season to play Minor League Baseball but returned to the Bulls in March 1995 and led them to three more championships in 1996, 1997, and 1998, as well as a then-record 72 regular season wins in the 1995–96 NBA season.[5] He retired for the second time in January 1999 but returned for two more NBA seasons from 2001 to 2003 as a member of the Washington Wizards.[5][13] During the course of his professional career he was also selected to play for the United States national team, winning four gold medals (at the 1983 Pan American Games, 1984 Summer Olympics, 1992 Tournament of the Americas and 1992 Summer Olympics), while also being undefeated.[15]

Jordan’s individual accolades and accomplishments include six NBA Finals Most Valuable Player (MVP) awards, ten NBA scoring titles (both all-time records), five NBA MVP awards, ten All-NBA First Team designations, nine All-Defensive First Team honors, fourteen NBA All-Star Game selections, three NBA All-Star Game MVP awards, three NBA steals titles, and the 1988 NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award.[13] He holds the NBA records for career regular season scoring average (30.12 points per game) and career playoff scoring average (33.4 points per game).[16] In 1999, he was named the 20th century’s greatest North American athlete by ESPN, and was second to Babe Ruth on the Associated Press’ list of athletes of the century.[5] Jordan was twice inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, once in 2009 for his individual career,[17] and again in 2010 as part of the 1992 United States men’s Olympic basketball team («The Dream Team»).[18] He became a member of the United States Olympic Hall of Fame in 2009,[19] a member of the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 2010,[20] and an individual member of the FIBA Hall of Fame in 2015 and a «Dream Team» member in 2017.[21][22] In 2021, Jordan was named to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team.[23]

One of the most effectively marketed athletes of his generation,[11] Jordan is known for his product endorsements.[24] He fueled the success of Nike’s Air Jordan sneakers, which were introduced in 1984 and remain popular today.[25] Jordan also starred as himself in the 1996 live-action animation hybrid film Space Jam and is the central focus of the Emmy Award-winning documentary miniseries The Last Dance (2020).[26] He became part-owner and head of basketball operations for the Charlotte Bobcats (now named the Hornets) in 2006,[25] and bought a controlling interest in 2010. In 2016, Jordan became the first billionaire player in NBA history.[27] That year, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[28] As of 2022, Jordan’s net worth is estimated at $1.7 billion.[29]

Early life

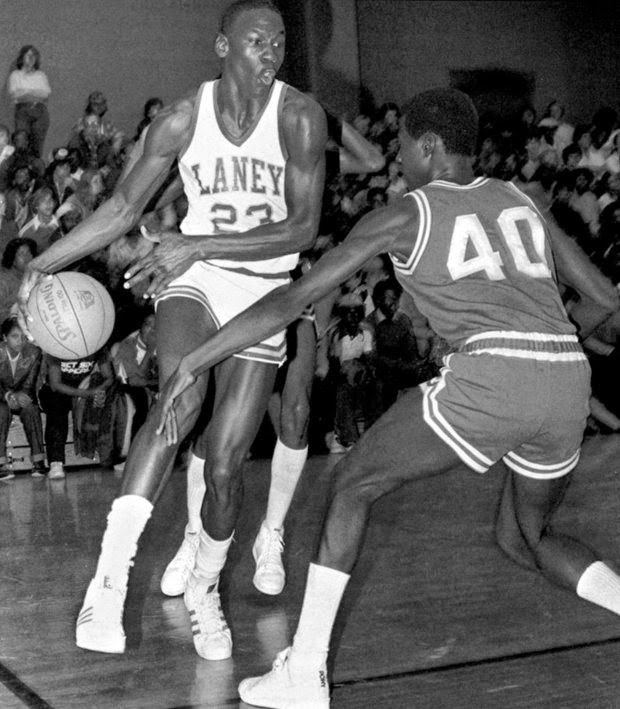

Jordan was born at Cumberland Hospital in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, New York City, on February 17, 1963,[30] the son of bank employee Deloris (née Peoples) and equipment supervisor James R. Jordan Sr.[30][31] In 1968, he moved with his family to Wilmington, North Carolina.[32] Jordan attended Emsley A. Laney High School in Wilmington, where he highlighted his athletic career by playing basketball, baseball, and football. He tried out for the basketball varsity team during his sophomore year; at 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m), he was deemed too short to play at that level. His taller friend Harvest Leroy Smith was the only sophomore to make the team.[33][34]

Motivated to prove his worth, Jordan became the star of Laney’s junior varsity team, and tallied some 40-point games.[33] The following summer, he grew four inches (10 cm) and trained rigorously.[34] Upon earning a spot on the varsity roster, Jordan averaged more than 25 points per game (ppg) over his final two seasons of high school play.[35] As a senior, he was selected to play in the 1981 McDonald’s All-American Game and scored 30 points,[36][37] after averaging 27 ppg,[35] 12 rebounds (rpg),[38][39] and six assists per game (apg) for the season.[39][40][41] Jordan was recruited by numerous college basketball programs, including Duke, North Carolina, South Carolina, Syracuse, and Virginia.[42] In 1981, he accepted a basketball scholarship to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he majored in cultural geography.[43]

College career

Jordan going in for a slam dunk for the Laney High School varsity basketball team, 1979–80

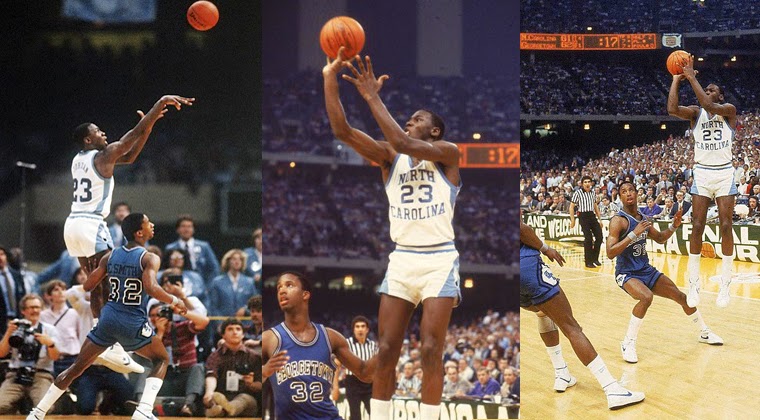

Jordan in action for North Carolina in 1983

As a freshman in coach Dean Smith’s team-oriented system, Jordan was named ACC Freshman of the Year after he averaged 13.4 ppg on 53.4% shooting (field goal percentage).[44] He made the game-winning jump shot in the 1982 NCAA Championship game against Georgetown, which was led by future NBA rival Patrick Ewing.[45] Jordan later described this shot as the major turning point in his basketball career.[46][47] During his three seasons with the Tar Heels, he averaged 17.7 ppg on 54.0% shooting, and added 5.0 rpg and 1.8 apg.[13]

Jordan was selected by consensus to the NCAA All-American First Team in both his sophomore (1983) and junior (1984) seasons.[48][49] After winning the Naismith and the Wooden College Player of the Year awards in 1984, Jordan left North Carolina one year before his scheduled graduation to enter the 1984 NBA draft. Jordan returned to North Carolina to complete his degree in 1986,[50] when he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in geography.[51] In 2002, Jordan was named to the ACC 50th Anniversary men’s basketball team honoring the 50 greatest players in ACC history.[52]

Professional career

Chicago Bulls (1984–1993; 1995–1998)

Early NBA years (1984–1987)

The Chicago Bulls selected Jordan with the third overall pick of the 1984 NBA draft after Hakeem Olajuwon (Houston Rockets) and Sam Bowie (Portland Trail Blazers). One of the primary reasons why Jordan was not drafted sooner was because the first two teams were in need of a center.[53] Trail Blazers general manager Stu Inman contended that it was not a matter of drafting a center but more a matter of taking Bowie over Jordan, in part because Portland already had Clyde Drexler, who was a guard with similar skills to Jordan.[54] Citing Bowie’s injury-laden college career, ESPN named the Blazers’ choice of Bowie as the worst draft pick in North American professional sports history.[55]

Jordan made his NBA debut at Chicago Stadium on October 26, 1984, and scored 16 points. In 2021, a ticket stub from the game sold at auction for $264,000, setting a record for a collectible ticket stub.[56] During his rookie 1984–85 season with the Bulls, Jordan averaged 28.2 ppg on 51.5% shooting,[44] and helped make a team that had won 35% of games in the previous three seasons playoff contenders. He quickly became a fan favorite even in opposing arenas.[57][58][59] Roy S. Johnson of The New York Times described him as «the phenomenal rookie of the Bulls» in November,[59] and Jordan appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the heading «A Star Is Born» in December.[60][61] The fans also voted in Jordan as an All-Star starter during his rookie season.[5] Controversy arose before the 1985 NBA All-Star Game when word surfaced that several veteran players, led by Isiah Thomas, were upset by the amount of attention Jordan was receiving.[5] This led to a so-called «freeze-out» on Jordan, where players refused to pass the ball to him throughout the game.[5] The controversy left Jordan relatively unaffected when he returned to regular season play, and he would go on to be voted the NBA Rookie of the Year.[62] The Bulls finished the season 38–44,[63] and lost to the Milwaukee Bucks in four games in the first round of the playoffs.[62]

An often-cited moment was on August 26, 1985,[35][64] when Jordan shook the arena during a Nike exhibition game in Trieste, Italy, by shattering the glass of the backboard with a dunk.[65][66] The moment was filmed and is often referred to worldwide as an important milestone in Jordan’s rise.[66][67] The shoes Jordan wore during the game were auctioned in August 2020 and sold for $615,000, a record for a pair of sneakers.[68][69] Jordan’s 1985–86 season was cut short when he broke his foot in the third game of the year, causing him to miss 64 games.[70] The Bulls made the playoffs despite Jordan’s injury and a 30–52 record,[63] at the time the fifth-worst record of any team to qualify for the playoffs in NBA history.[71] Jordan recovered in time to participate in the postseason and performed well upon his return. Against a Boston Celtics team that is often considered one of the greatest in NBA history,[72] Jordan set the still-unbroken record for points in a playoff game with 63 in Game 2,[73] but the Celtics managed to sweep the series.[62]

Jordan completely recovered in time for the 1986–87 season,[74] and had one of the most prolific scoring seasons in NBA history; he became the only player other than Wilt Chamberlain to score 3,000 points in a season, averaging a league-high 37.1 ppg on 48.2% shooting.[44][75] In addition, Jordan demonstrated his defensive prowess, as he became the first player in NBA history to record 200 steals and 100 blocked shots in a season.[76] Despite Jordan’s success, Magic Johnson won the NBA Most Valuable Player Award.[77] The Bulls reached 40 wins,[63] and advanced to the playoffs for the third consecutive year but were again swept by the Celtics.[62]

Pistons roadblock (1987–1990)

Jordan again led the league in scoring during the 1987–88 season, averaging 35.0 ppg on 53.5% shooting,[44] and he won his first league MVP Award. He was also named the NBA Defensive Player of the Year, as he averaged 1.6 blocks per game (bpg), a league-high 3.1 steals per game (spg),[78] and led the Bulls defense to the fewest points per game allowed in the league.[79] The Bulls finished 50–32,[63] and made it out of the first round of the playoffs for the first time in Jordan’s career, as they defeated the Cleveland Cavaliers in five games.[80] In the Eastern Conference Semifinals, the Bulls lost in five games to the more experienced Detroit Pistons,[62] who were led by Isiah Thomas and a group of physical players known as the «Bad Boys».[81]

In the 1988–89 season, Jordan again led the league in scoring, averaging 32.5 ppg on 53.8% shooting from the field, along with 8 rpg and 8 apg.[44] During the season, Sam Vincent, Chicago’s point guard, was having trouble running the offense, and Jordan expressed his frustration with head coach Doug Collins, who would put Jordan at point guard. In his time as a point guard, Jordan averaged 10 triple-doubles in eleven games, with 33.6 ppg, 11.4 rpg, 10.8 apg, 2.9 spg, and 0.8 bpg on 51% shooting.[82]

The Bulls finished with a 47–35 record,[63] and advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals, defeating the Cavaliers and New York Knicks along the way.[83] The Cavaliers series included a career highlight for Jordan when he hit «The Shot» over Craig Ehlo at the buzzer in the fifth and final game of the series.[84] In the Eastern Conference Finals, the Pistons again defeated the Bulls, this time in six games,[62] by utilizing their «Jordan Rules» method of guarding Jordan, which consisted of double and triple teaming him every time he touched the ball.[5]

The Bulls entered the 1989–90 season as a team on the rise, with their core group of Jordan and young improving players like Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant, and under the guidance of new coach Phil Jackson.[85] On March 28, 1990, Jordan scored a career-high 69 points in a 117–113 road win over the Cavaliers.[86] He averaged a league-leading 33.6 ppg on 52.6% shooting, to go with 6.9 rpg and 6.3 apg,[44] in leading the Bulls to a 55–27 record.[63] They again advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals after beating the Bucks and Philadelphia 76ers;[87] despite pushing the series to seven games, the Bulls lost to the Pistons for the third consecutive season.[62]

First three-peat (1991–1993)

In the 1990–91 season, Jordan won his second MVP award after averaging 31.5 ppg on 53.9% shooting, 6.0 rpg, and 5.5 apg for the regular season.[44] The Bulls finished in first place in their division for the first time in sixteen years and set a franchise record with 61 wins in the regular season.[63] With Scottie Pippen developing into an All-Star, the Bulls had elevated their play. The Bulls defeated the New York Knicks and the Philadelphia 76ers in the opening two rounds of the playoffs. They advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals where their rival, the Detroit Pistons, awaited them;[88] this time, the Bulls beat the Pistons in a four-game sweep.[89]

The Bulls advanced to the Finals for the first time in franchise history to face the Los Angeles Lakers, who had Magic Johnson and James Worthy, two formidable opponents. The Bulls won the series four games to one, and compiled a 15–2 playoff record along the way.[88] Perhaps the best-known moment of the series came in Game 2 when, attempting a dunk, Jordan avoided a potential Sam Perkins block by switching the ball from his right hand to his left in mid-air to lay the shot into the basket.[90] In his first Finals appearance, Jordan had 31.2 ppg on 56% shooting from the field, 11.4 apg, 6.6 rpg, 2.8 spg, and 1.4 bpg.[91] Jordan won his first NBA Finals MVP award,[92] and he cried while holding the Finals trophy.[93]

Jordan and the Bulls continued their dominance in the 1991–92 season, establishing a 67–15 record, topping their franchise record from 1990–91.[63] Jordan won his second consecutive MVP award with averages of 30.1 ppg, 6.4 rbg, and 6.1 apg on 52% shooting.[78] After winning a physical seven-game series over the New York Knicks in the second round of the playoffs and finishing off the Cleveland Cavaliers in the Conference Finals in six games, the Bulls met Clyde Drexler and the Portland Trail Blazers in the Finals. The media, hoping to recreate a Magic–Bird rivalry, highlighted the similarities between «Air» Jordan and Clyde «The Glide» during the pre-Finals hype.[94]

In the first game, Jordan scored a Finals-record 35 points in the first half, including a record-setting six three-point field goals.[95] After the sixth three-pointer, he jogged down the court shrugging as he looked courtside. Marv Albert, who broadcast the game, later stated that it was as if Jordan was saying: «I can’t believe I’m doing this.»[96] The Bulls went on to win Game 1 and defeat the Blazers in six games. Jordan was named Finals MVP for the second year in a row,[92] and finished the series averaging 35.8 ppg, 4.8 rpg, and 6.5 apg, while shooting 52.6% from the floor.[97]

In the 1992–93 season, despite a 32.6 ppg, 6.7 rpg, and 5.5 apg campaign, including a second-place finish in Defensive Player of the Year voting,[78][98] Jordan’s streak of consecutive MVP seasons ended, as he lost the award to his friend Charles Barkley,[77] which upset him.[99] Coincidentally, Jordan and the Bulls met Barkley and his Phoenix Suns in the 1993 NBA Finals. The Bulls won their third NBA championship on a game-winning shot by John Paxson and a last-second block by Horace Grant, but Jordan was once again Chicago’s leader. He averaged a Finals-record 41.0 ppg during the six-game series,[100] and became the first player in NBA history to win three straight Finals MVP awards.[92] He scored more than 30 points in every game of the series, including 40 or more points in four consecutive games.[101] With his third Finals triumph, Jordan capped off a seven-year run where he attained seven scoring titles and three championships, but there were signs that Jordan was tiring of his massive celebrity and all of the non-basketball hassles in his life.[102]

Gambling

During the Bulls’ 1993 NBA playoffs, Jordan was seen gambling in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the night before Game 2 of the Eastern Conference Finals against the New York Knicks.[103] The previous year, he admitted that he had to cover $57,000 in gambling losses,[104] and author Richard Esquinas wrote a book in 1993 claiming he had won $1.25 million from Jordan on the golf course.[105] David Stern, the commissioner of the NBA, denied in 1995 and 2006 that Jordan’s 1993 retirement was a secret suspension by the league for gambling,[106][107] but the rumor spread widely.[108]

In 2005, Jordan discussed his gambling with Ed Bradley of 60 Minutes and admitted that he made reckless decisions. Jordan stated: «Yeah, I’ve gotten myself into situations where I would not walk away and I’ve pushed the envelope. Is that compulsive? Yeah, it depends on how you look at it. If you’re willing to jeopardize your livelihood and your family, then yeah.» When Bradley asked him if his gambling ever got to the level where it jeopardized his livelihood or family, Jordan replied: «No.»[109] In 2010, Ron Shelton, director of Jordan Rides the Bus, said that he began working on the documentary believing that the NBA had suspended him, but that research «convinced [him it] was nonsense».[108]

First retirement and stint in Minor League Baseball (1993–1995)

| Michael Jordan | |

|---|---|

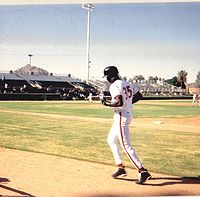

Jordan in training with the Scottsdale Scorpions in 1994 | |

| Birmingham Barons – No. 45, 35 | |

| Outfielder | |

| Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| Professional debut | |

| Southern League: April 8, 1994, for the Birmingham Barons | |

| Arizona Fall League: 1994, for the Scottsdale Scorpions | |

| Last Southern League appearance | |

| March 10, 1995, for the Birmingham Barons | |

| Southern League statistics (through 1994) | |

| Batting average | .202 |

| Home runs | 3 |

| Runs batted in | 51 |

| Arizona Fall League statistics | |

| Batting average | .252 |

| Runs batted in | 8 |

| Teams | |

|

On October 6, 1993, Jordan announced his retirement, saying that he lost his desire to play basketball. Jordan later said that the murder of his father three months earlier helped shape his decision.[110] James R. Jordan Sr. was murdered on July 23, 1993, at a highway rest area in Lumberton, North Carolina, by two teenagers, Daniel Green and Larry Martin Demery, who carjacked his Lexus bearing the license plate «UNC 0023».[111][112] His body, dumped in a South Carolina swamp, was not discovered until August 3.[112] Green and Demery were found after they made calls on James Jordan’s cell phone,[113] convicted at a trial, and sentenced to life in prison.[114]

Jordan was close to his father; as a child, he imitated the way his father stuck out his tongue while absorbed in work. He later adopted it as his own signature, often displaying it as he drove to the basket.[5] In 1996, he founded a Chicago-area Boys & Girls Club and dedicated it to his father.[115][116] In his 1998 autobiography For the Love of the Game, Jordan wrote that he was preparing for retirement as early as the summer of 1992.[117] The added exhaustion due to the «Dream Team» run in the 1992 Summer Olympics solidified Jordan’s feelings about the game and his ever-growing celebrity status. Jordan’s announcement sent shock waves throughout the NBA and appeared on the front pages of newspapers around the world.[118]

Jordan further surprised the sports world by signing a Minor League Baseball contract with the Chicago White Sox on February 7, 1994.[119] He reported to spring training in Sarasota, Florida, and was assigned to the team’s minor league system on March 31, 1994.[120] Jordan said that this decision was made to pursue the dream of his late father, who always envisioned his son as a Major League Baseball player.[121] The White Sox were owned by Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who continued to honor Jordan’s basketball contract during the years he played baseball.[122]

In 1994, Jordan played for the Birmingham Barons, a Double-A minor league affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, batting .202 with three home runs, 51 runs batted in, 30 stolen bases, 114 strikeouts, 51 bases on balls, and 11 errors.[123][124] His strikeout total led the team and his games played tied for the team lead. His 30 stolen bases were second on the team only to Doug Brady.[125] He also appeared for the Scottsdale Scorpions in the 1994 Arizona Fall League, batting .252 against the top prospects in baseball.[120] On November 1, 1994, his No. 23 was retired by the Bulls in a ceremony that included the erection of a permanent sculpture known as The Spirit outside the new United Center.[126][127][128]

«I’m back»: Return to the NBA (1995)

The Bulls went 55–27 in 1993–94 without Jordan in the lineup,[63] and lost to the New York Knicks in the second round of the playoffs.[129] The 1994–95 Bulls were a shell of the championship team of just two years earlier. Struggling at mid-season to ensure a spot in the playoffs, Chicago was 31–31 at one point in mid-March;[130] the team received help when Jordan decided to return to the Bulls.[131]

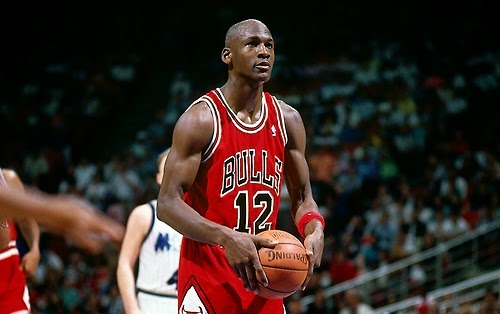

In March 1995, Jordan decided to quit baseball because he feared he might become a replacement player during the Major League Baseball strike.[132] On March 18, 1995, Jordan announced his return to the NBA through a two-word press release: «I’m back.»[133] The next day, Jordan took to the court with the Bulls to face the Indiana Pacers in Indianapolis, scoring 19 points.[134] The game had the highest Nielsen rating of any regular season NBA game since 1975.[135] Although he could have worn his original number even though the Bulls retired it, Jordan wore No. 45, his baseball number.[134]

Despite his eighteen-month hiatus from the NBA, Jordan played well, making a game-winning jump shot against Atlanta in his fourth game back. He scored 55 points in his next game, against the New York Knicks at Madison Square Garden on March 28, 1995.[62] Boosted by Jordan’s comeback, the Bulls went 13–4 to make the playoffs and advanced to the Eastern Conference Semifinals against the Orlando Magic.[136] At the end of Game 1, Orlando’s Nick Anderson stripped Jordan from behind, leading to the game-winning basket for the Magic; he later commented that Jordan «didn’t look like the old Michael Jordan»,[137] and said that «No. 45 doesn’t explode like No. 23 used to».[138]

Jordan responded by scoring 38 points in the next game, which Chicago won. Before the game, Jordan decided that he would immediately resume wearing his former No. 23. The Bulls were fined $25,000 for failing to report the impromptu number change to the NBA.[138] Jordan was fined an additional $5,000 for opting to wear white sneakers when the rest of the Bulls wore black.[139] He averaged 31 ppg in the playoffs, but Orlando won the series in six games.[140]

Second three-peat (1995–1998)

Jordan was freshly motivated by the playoff defeat, and he trained aggressively for the 1995–96 season.[141] The Bulls were strengthened by the addition of rebound specialist Dennis Rodman, and the team dominated the league, starting the season at 41–3.[142] The Bulls eventually finished with the best regular season record in NBA history, 72–10, a mark broken two decades later by the 2015–16 Golden State Warriors.[143] Jordan led the league in scoring with 30.4 ppg,[144] and he won the league’s regular season and All-Star Game MVP awards.[13]

In the playoffs, the Bulls lost only three games in four series (Miami Heat 3–0, New York Knicks 4–1, and Orlando Magic 4–0), as they defeated the Seattle SuperSonics 4–2 in the NBA Finals to win their fourth championship.[142] Jordan was named Finals MVP for a record fourth time, surpassing Magic Johnson’s three Finals MVP awards;[92] he also achieved only the second sweep of the MVP awards in the All-Star Game, regular season, and NBA Finals after Willis Reed in the 1969–70 season.[62] Upon winning the championship, his first since his father’s murder, Jordan reacted emotionally, clutching the game ball and crying on the locker room floor.[5][93]

In the 1996–97 season, the Bulls stood at a 69–11 record but ended the season by losing their final two games to finish the year 69–13, missing out on a second consecutive 70-win season.[145] The Bulls again advanced to the Finals, where they faced the Utah Jazz.[146] That team included Karl Malone, who had beaten Jordan for the NBA MVP award in a tight race (986–957).[147][148][149] The series against the Jazz featured two of the more memorable clutch moments of Jordan’s career. He won Game 1 for the Bulls with a buzzer-beating jump shot. In Game 5, with the series tied at 2, Jordan played despite being feverish and dehydrated from a stomach virus. In what is known as «The Flu Game», Jordan scored 38 points, including the game-deciding 3-pointer with 25 seconds remaining.[146] The Bulls won 90–88 and went on to win the series in six games.[145] For the fifth time in as many Finals appearances, Jordan received the Finals MVP award.[92] During the 1997 NBA All-Star Game, Jordan posted the first triple-double in All-Star Game history in a victorious effort, but the MVP award went to Glen Rice.[150]

Jordan and the Bulls compiled a 62–20 record in the 1997–98 season.[63] Jordan led the league with 28.7 ppg,[78] securing his fifth regular season MVP award, plus honors for All-NBA First Team, First Defensive Team, and the All-Star Game MVP.[13] The Bulls won the Eastern Conference Championship for a third straight season, including surviving a seven-game series with the Indiana Pacers in the Eastern Conference Finals; it was the first time Jordan had played in a Game 7 since the 1992 Eastern Conference Semifinals with the New York Knicks.[151][152] After winning, they moved on for a rematch with the Jazz in the Finals.[153]

The Bulls returned to the Delta Center for Game 6 on June 14, 1998, leading the series 3–2. Jordan executed a series of plays, considered to be one of the greatest clutch performances in NBA Finals history.[154] With 41.9 seconds remaining and the Bulls trailing 86–83, Phil Jackson called a timeout. When play resumed, Jordan received the inbound pass, drove to the basket, and sank a shot over several Jazz defenders, cutting Utah’s lead to 86–85.[154] The Jazz brought the ball upcourt and passed the ball to Malone, who was set up in the low post and was being guarded by Rodman. Malone jostled with Rodman and caught the pass, but Jordan cut behind him and stole the ball out of his hands.[154]

Jordan then dribbled down the court and paused, eyeing his defender, Jazz guard Bryon Russell. With 10 seconds remaining, Jordan started to dribble right, then crossed over to his left, possibly pushing off Russell, although the officials did not call a foul.[155][156][157][158] With 5.2 seconds left, Jordan made the climactic shot of his Bulls career,[159] a top-key jumper over a stumbling Russell to give Chicago an 87–86 lead. Afterwards, the Jazz’ John Stockton narrowly missed a game-winning three-pointer, and the buzzer sounded as Jordan and the Bulls won their sixth NBA championship,[160] achieving a second three-peat in the decade.[161] Once again, Jordan was voted Finals MVP,[92] having led all scorers by averaging 33.5 ppg, including 45 in the deciding Game 6.[162] Jordan’s six Finals MVPs is a record.[163] The 1998 Finals holds the highest television rating of any Finals series in history,[164] and Game 6 holds the highest television rating of any game in NBA history.[165]

Second retirement (1999–2001)

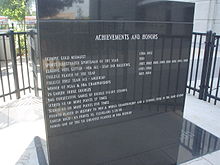

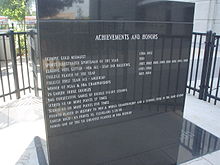

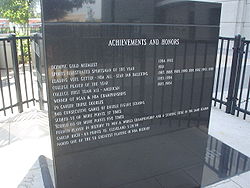

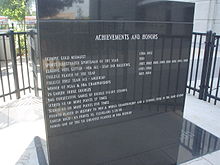

Plaque at the United Center that chronicles Jordan’s career achievements

With Phil Jackson’s contract expiring, the pending departures of Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman looming, and being in the latter stages of an owner-induced lockout of NBA players, Jordan retired for the second time on January 13, 1999.[166][167][168] On January 19, 2000, Jordan returned to the NBA not as a player but as part owner and president of basketball operations for the Washington Wizards.[169] Jordan’s responsibilities with the Wizards were comprehensive, as he controlled all aspects of the Wizards’ basketball operations, and had the final say in all personnel matters; opinions of Jordan as a basketball executive were mixed.[170][171] He managed to purge the team of several highly paid, unpopular players (like forward Juwan Howard and point guard Rod Strickland)[172][173] but used the first pick in the 2001 NBA draft to select high schooler Kwame Brown, who did not live up to expectations and was traded away after four seasons.[170][174]

Despite his January 1999 claim that he was «99.9% certain» he would never play another NBA game,[93] Jordan expressed interest in making another comeback in the summer of 2001, this time with his new team.[175][176] Inspired by the NHL comeback of his friend Mario Lemieux the previous winter,[177] Jordan spent much of the spring and summer of 2001 in training, holding several invitation-only camps for NBA players in Chicago.[178] In addition, Jordan hired his old Chicago Bulls head coach, Doug Collins, as Washington’s coach for the upcoming season, a decision that many saw as foreshadowing another Jordan return.[175][176]

Washington Wizards (2001–2003)

On September 25, 2001, Jordan announced his return to the NBA to play for the Washington Wizards, indicating his intention to donate his salary as a player to a relief effort for the victims of the September 11 attacks.[179][180] In an injury-plagued 2001–02 season, Jordan led the team in scoring (22.9 ppg), assists (5.2 apg), and steals (1.4 spg),[5] and was an MVP candidate, as he led the Wizards to a winning record and playoff contention;[181][182] he would eventually finish 13th in the MVP ballot.[183] After suffering torn cartilage in his right knee,[184] and subsequent knee soreness,[185] the Wizards missed the playoffs,[186] and Jordan’s season ended after only 60 games, the fewest he had played in a regular season since playing 17 games after returning from his first retirement during the 1994–95 season.[44] Jordan started 53 of his 60 games for the season, averaging 24.3 ppg, 5.4 apg, and 6.0 rpg, and shooting 41.9% from the field in his 53 starts. His last seven appearances were in a reserve role, in which he averaged just over 20 minutes per game.[187] The Wizards finished the season with a 37–45 record, an 18-game improvement.[186]

Jordan as a member of the Washington Wizards, April 14, 2003

Playing in his 14th and final NBA All-Star Game in 2003, Jordan passed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the all-time leading scorer in All-Star Game history, a record since broken by Kobe Bryant and LeBron James.[188][189] That year, Jordan was the only Washington player to play in all 82 games, starting in 67 of them, and coming from off the bench in 15. He averaged 20.0 ppg, 6.1 rpg, 3.8 assists, and 1.5 spg per game.[5] He also shot 45% from the field, and 82% from the free-throw line.[44] Even though he turned 40 during the season, he scored 20 or more points 42 times, 30 or more points nine times, and 40 or more points three times.[62] On February 21, 2003, Jordan became the first 40-year-old to tally 43 points in an NBA game.[190] During his stint with the Wizards, all of Jordan’s home games at the MCI Center were sold out and the Wizards were the second most-watched team in the NBA, averaging 20,172 fans a game at home and 19,311 on the road.[191] Jordan’s final two seasons did not result in a playoff appearance for the Wizards, and he was often unsatisfied with the play of those around him.[192][193] At several points, he openly criticized his teammates to the media, citing their lack of focus and intensity, notably that of Kwame Brown, the number-one draft pick in the 2001 NBA draft.[192][193]

Final retirement (2003)

With the recognition that 2002–03 would be Jordan’s final season, tributes were paid to him throughout the NBA. In his final game at the United Center in Chicago, which was his old home court, Jordan received a four-minute standing ovation.[194] The Miami Heat retired the No. 23 jersey on April 11, 2003, even though Jordan never played for the team.[195] At the 2003 All-Star Game, Jordan was offered a starting spot from Tracy McGrady and Allen Iverson but refused both;[196] in the end, he accepted the spot of Vince Carter.[197] Jordan played in his final NBA game on April 16, 2003, in Philadelphia. After scoring 13 points in the game, Jordan went to the bench with 4 minutes and 13 seconds remaining in the third quarter and his team trailing the Philadelphia 76ers 75–56. Just after the start of the fourth quarter, the First Union Center crowd began chanting «We want Mike!» After much encouragement from coach Doug Collins, Jordan finally rose from the bench and re-entered the game, replacing Larry Hughes with 2:35 remaining. At 1:45, Jordan was intentionally fouled by the 76ers’ Eric Snow, and stepped to the line to make both free throws. After the second foul shot, the 76ers in-bounded the ball to rookie John Salmons, who in turn was intentionally fouled by Bobby Simmons one second later, stopping time so that Jordan could return to the bench. Jordan received a three-minute standing ovation from his teammates, his opponents, the officials, and the crowd of 21,257 fans.[198]

National team career

Jordan on the «Dream Team» in 1992

Jordan made his debut for the U.S. national basketball team at the 1983 Pan American Games in Caracas, Venezuela. He led the team in scoring with 17.3 ppg as the U.S., coached by Jack Hartman, won the gold medal in the competition.[199][200] A year later, he won another gold medal in the 1984 Summer Olympics. The 1984 U.S. team was coached by Bob Knight and featured players such as Patrick Ewing, Sam Perkins, Chris Mullin, Steve Alford, and Wayman Tisdale. Jordan led the team in scoring, averaging 17.1 ppg for the tournament.[201]

In 1992, Jordan was a member of the star-studded squad that was dubbed the «Dream Team», which included Larry Bird and Magic Johnson. The team went on to win two gold medals: the first one in the 1992 Tournament of the Americas,[202] and the second one in the 1992 Summer Olympics. He was the only player to start all eight games in the Olympics, averaged 14.9 ppg, and finished second on the team in scoring.[203] Jordan was undefeated in the four tournaments he played for the United States national team, winning all 30 games he took part in.[15]

Player profile

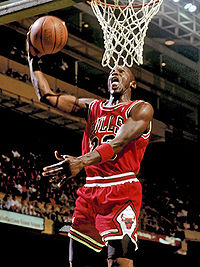

Jordan dunking the ball, 1987–88

Jordan was a shooting guard who could also play as a small forward, the position he would primarily play during his second return to professional basketball with the Washington Wizards,[13] and as a point guard.[82] Jordan was known throughout his career as a strong clutch performer. With the Bulls, he decided 25 games with field goals or free throws in the last 30 seconds, including two NBA Finals games and five other playoff contests.[204] His competitiveness was visible in his prolific trash talk and well-known work ethic.[205][206][207] Jordan often used perceived slights to fuel his performances. Sportswriter Wright Thompson described him as «a killer, in the Darwinian sense of the word, immediately sensing and attacking someone’s weakest spot».[3] As the Bulls organization built the franchise around Jordan, management had to trade away players who were not «tough enough» to compete with him in practice. To help improve his defense, he spent extra hours studying film of opponents. On offense, he relied more upon instinct and improvization at game time.[208]

Noted as a durable player, Jordan did not miss four or more games while active for a full season from 1986–87 to 2001–02, when he injured his right knee.[13][209] Of the 15 seasons Jordan was in the NBA, he played all 82 regular season games nine times.[13] Jordan has frequently cited David Thompson, Walter Davis, and Jerry West as influences.[210][211] Confirmed at the start of his career, and possibly later on, Jordan had a special «Love of the Game Clause» written into his contract, which was unusual at the time, and allowed him to play basketball against anyone at any time, anywhere.[212]

Jordan had a versatile offensive game and was capable of aggressively driving to the basket as well as drawing fouls from his opponents at a high rate. His 8,772 free throw attempts are the 11th-highest total in NBA history.[213] As his career progressed, Jordan also developed the ability to post up his opponents and score with his trademark fadeaway jump shot, using his leaping ability to avoid block attempts. According to Hubie Brown, this move alone made him nearly unstoppable.[214] Despite media criticism by some as a selfish player early in his career, Jordan was willing to defer to this teammates, with a career average of 5.3 apg and a season-high of 8.0 apg.[44] For a guard, Jordan was also a good rebounder, finishing with 6.2 rpg. Defensively, he averaged 2.3 spg and 0.8 bpg.[44]

Three-point field goal was not Jordan’s strength, especially in his early years. Later on in Jordan’s career, he improved his three-point shooting, and finished his career with a respectable 32% success rate.[44] His three-point field-goal percentages ranged from 35% to 43% in seasons in which he attempted at least 230 three-pointers between 1989–90 and 1996–97.[13] Jordan’s effective field goal percentage was 50%, and he had six seasons with at least 50% shooting, five of which consecutively (1988–1992); he also shot 51% and 50%, and 30% and 33% from the three-point range, throughout his first and second retirements, respectively, finishing his Chicago Bulls career with 31.5 points per game on 50.5 FG% shooting and his overall career with 49.7 FG% shooting.[13]

Unlike NBA players often compared to Jordan, such as Kobe Bryant and LeBron James, who had a similar three-point percentage, he did not shoot as many threes as they did, as he did not need to rely on the three-pointer in order to be effective on offense. Three-point shooting was only introduced in 1979 and would not be a more fundamental aspect of the game until the first decades of the 21st century,[215] with the NBA having to briefly shorten the line to incentivize more shots.[216] Jordan’s three-point shooting was better selected, resulting in three-point field goals made in important games during the playoffs and the Finals, such as hitting six consecutive three-point shots in Game 1 of the 1992 NBA Finals. Jordan shot 37%, 35%, 42%, and 37% in all the seasons he shot over 200 three-pointers, and also shot 38.5%, 38.6%, 38.9%, 40.3%, 19.4%, and 30.2% in the playoffs during his championship runs, improving his shooting even after the three-point line reverted to the original line.[217][218][219]

In 1988, Jordan was honored with the NBA Defensive Player of the Year and the Most Valuable Player awards, becoming the first NBA player to win both awards in a career let alone season. In addition, he set both seasonal and career records for blocked shots by a guard,[220] and combined this with his ball-thieving ability to become a standout defensive player. He ranks third in NBA history in total steals with 2,514, trailing John Stockton and Jason Kidd.[221] Jerry West often stated that he was more impressed with Jordan’s defensive contributions than his offensive ones.[222] Doc Rivers declared Jordan «the best superstar defender in the history of the game».[223]

Jordan was known to have strong eyesight. Broadcaster Al Michaels said that he was able to read baseball box scores on a 27-inch (69 cm) television clearly from about 50 feet (15 m) away.[224] During the 2001 NBA Finals, Phil Jackson compared Jordan’s dominance to Shaquille O’Neal, stating: «Michael would get fouled on every play and still have to play through it and just clear himself for shots instead and would rise to that occasion.»[225]

Legacy

Jordan’s talent was clear from his first NBA season; by November 1984, he was being compared to Julius Erving.[57][59] Larry Bird said that rookie Jordan was the best player he ever saw, and that he was «one of a kind», and comparable to Wayne Gretzky as an athlete.[226] In his first game in Madison Square Garden against the New York Knicks, Jordan received a near minute-long standing ovation.[59] After establishing the single game playoff record of 63 points against the Boston Celtics on April 20, 1986, Bird described him as «God disguised as Michael Jordan».[73]

Jordan led the NBA in scoring in 10 seasons (NBA record) and tied Wilt Chamberlain’s record of seven consecutive scoring titles.[5] He was also a fixture of the NBA All-Defensive First Team, making the roster nine times (NBA record shared with Gary Payton, Kevin Garnett, and Kobe Bryant).[227] Jordan also holds the top career regular season and playoff scoring averages of 30.1 and 33.4 ppg, respectively.[16][228] By 1998, the season of his Finals-winning shot against the Jazz, he was well known throughout the league as a clutch performer. In the regular season, Jordan was the Bulls’ primary threat in the final seconds of a close game and in the playoffs; he would always ask for the ball at crunch time.[229] Jordan’s total of 5,987 points in the playoffs is the second-highest among NBA career playoff scoring leaders.[230] He retired with 32,292 points in regular season play,[231] placing him fifth on the NBA all-time scoring list behind Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, LeBron James, Karl Malone, and Bryant.[231]

With five regular season MVPs (tied for second place with Bill Russell—only Abdul-Jabbar has won more, with six), six Finals MVPs (NBA record), and three NBA All-Star Game MVPs, Jordan is the most decorated player in NBA history.[13][232] Jordan finished among the top three in regular season MVP voting 10 times.[13] He was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996,[233] and selected to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021.[23] Jordan is one of only seven players in history to win an NCAA championship, an NBA championship, and an Olympic gold medal (doing so twice with the 1984 and 1992 U.S. men’s basketball teams).[234] Since 1976, the year of the ABA–NBA merger,[235] Jordan and Pippen are the only two players to win six NBA Finals playing for one team.[236] In the All-Star Game fan ballot, Jordan received the most votes nine times, more than any other player.[237]

«There’s Michael Jordan and then there is the rest of us.»

—Magic Johnson[5]

Many of Jordan’s contemporaries have said that Jordan is the greatest basketball player of all time.[222] In 1999, an ESPN survey of journalists, athletes and other sports figures ranked Jordan the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century, above Babe Ruth and Muhammad Ali.[238] Jordan placed second to Ruth in the Associated Press’ December 1999 list of 20th century athletes.[239] In addition, the Associated Press voted him the greatest basketball player of the 20th century.[240] Jordan has also appeared on the front cover of Sports Illustrated a record 50 times.[241] In the September 1996 issue of Sport, which was the publication’s 50th-anniversary issue, Jordan was named the greatest athlete of the past 50 years.[242]

Jordan’s athletic leaping ability, highlighted in his back-to-back Slam Dunk Contest championships in 1987 and 1988, is credited by many people with having influenced a generation of young players.[243][244] Several NBA players, including James and Dwyane Wade, have stated that they considered Jordan their role model while they were growing up.[245][246] In addition, commentators have dubbed a number of next-generation players «the next Michael Jordan» upon their entry to the NBA, including Penny Hardaway, Grant Hill, Allen Iverson, Bryant, Vince Carter, James, and Wade.[247][248][249] Some analysts, such as The Ringer’s Dan Devine, drew parallels between Jordan’s experiment at point guard in the 1988–89 season and the modern NBA; for Devine, it «inadvertently foreshadowed the modern game’s stylistic shift toward monster-usage primary playmakers», such as Russell Westbrook, James Harden, Luka Dončić, and James.[250] Don Nelson stated: «I would’ve been playing him at point guard the day he showed up as a rookie.»[251]

Although Jordan was a well-rounded player, his «Air Jordan» image is also often credited with inadvertently decreasing the jump shooting skills, defense, and fundamentals of young players,[243] a fact Jordan himself has lamented, saying: «I think it was the exposure of Michael Jordan; the marketing of Michael Jordan. Everything was marketed towards the things that people wanted to see, which was scoring and dunking. That Michael Jordan still played defense and an all-around game, but it was never really publicized.»[243] During his heyday, Jordan did much to increase the status of the game; television ratings increased only during his time in the league.[252] The popularity of the NBA in the U.S. declined after his last title.[252] As late as 2020, NBA Finals television ratings had not returned to the level reached during his last championship-winning season.[253]

In August 2009, the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts, opened a Michael Jordan exhibit that contained items from his college and NBA careers as well as from the 1992 «Dream Team»; the exhibit also has a batting baseball glove to signify Jordan’s short career in the Minor League Baseball.[254] After Jordan received word of his acceptance into the Hall of Fame, he selected Class of 1996 member David Thompson to present him.[255] As Jordan would later explain during his induction speech in September 2009, he was not a fan of the Tar Heels when growing up in North Carolina but greatly admired Thompson, who played for the rival NC State Wolfpack. In September, he was inducted into the Hall with several former Bulls teammates in attendance, including Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman, Charles Oakley, Ron Harper, Steve Kerr, and Toni Kukoč.[17] Dean Smith and Doug Collins, two of Jordan’s former coaches, were also among those present. His emotional reaction during his speech when he began to cry was captured by Associated Press photographer Stephan Savoia and would later go viral on social media as the «Crying Jordan» Internet meme.[256][257] In 2016, President Barack Obama honored Jordan with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[28] In October 2021, Jordan was named to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team.[23] In September 2022, Jordan’s jersey in which he played the opening game of the 1998 NBA Finals was sold for $10.1 million, making it the most expensive game-worn sports memorabilia in history.[258]

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league | | NBA record |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–85 | Chicago | 82* | 82* | 38.3 | .515 | .173 | .845 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 2.4 | .8 | 28.2 |

| 1985–86 | Chicago | 18 | 7 | 25.1 | .457 | .167 | .840 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 22.7 |

| 1986–87 | Chicago | 82* | 82* | 40.0 | .482 | .182 | .857 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 37.1* |

| 1987–88 | Chicago | 82 | 82* | 40.4* | .535 | .132 | .841 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 3.2* | 1.6 | 35.0* |

| 1988–89 | Chicago | 81 | 81 | 40.2* | .538 | .276 | .850 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 2.9 | .8 | 32.5* |

| 1989–90 | Chicago | 82* | 82* | 39.0 | .526 | .376 | .848 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 2.8* | .7 | 33.6* |

| 1990–91† | Chicago | 82* | 82* | 37.0 | .539 | .312 | .851 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 31.5* |

| 1991–92† | Chicago | 80 | 80 | 38.8 | .519 | .270 | .832 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 2.3 | .9 | 30.1* |

| 1992–93† | Chicago | 78 | 78 | 39.3 | .495 | .352 | .837 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 2.8* | .8 | 32.6* |

| 1994–95 | Chicago | 17 | 17 | 39.3 | .411 | .500 | .801 | 6.9 | 5.3 | 1.8 | .8 | 26.9 |

| 1995–96† | Chicago | 82 | 82* | 37.7 | .495 | .427 | .834 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 2.2 | .5 | 30.4* |

| 1996–97† | Chicago | 82 | 82* | 37.9 | .486 | .374 | .833 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 1.7 | .5 | 29.6* |

| 1997–98† | Chicago | 82* | 82* | 38.8 | .465 | .238 | .784 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 1.7 | .5 | 28.7* |

| 2001–02 | Washington | 60 | 53 | 34.9 | .416 | .189 | .790 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 1.4 | .4 | 22.9 |

| 2002–03 | Washington | 82 | 67 | 37.0 | .445 | .291 | .821 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 1.5 | .5 | 20.0 |

| Career[13] | 1,072 | 1,039 | 38.3 | .497 | .327 | .835 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 2.3 | .8 | 30.1 | |

| All-Star[13] | 13 | 13 | 29.4 | .472 | .273 | .750 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 2.8 | .5 | 20.2 |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Chicago | 4 | 4 | 42.8 | .436 | .125 | .828 | 5.8 | 8.5 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 29.3 |

| 1986 | Chicago | 3 | 3 | 45.0 | .505 | 1.000 | .872 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 43.7 |

| 1987 | Chicago | 3 | 3 | 42.7 | .417 | .400 | .897 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 35.7 |

| 1988 | Chicago | 10 | 10 | 42.7 | .531 | .333 | .869 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 36.3 |

| 1989 | Chicago | 17 | 17 | 42.2 | .510 | .286 | .799 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 2.5 | .8 | 34.8 |

| 1990 | Chicago | 16 | 16 | 42.1 | .514 | .320 | .836 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 2.8 | .9 | 36.7 |

| 1991† | Chicago | 17 | 17 | 40.5 | .524 | .385 | .845 | 6.4 | 8.4 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 31.1 |

| 1992† | Chicago | 22 | 22 | 41.8 | .499 | .386 | .857 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 2.0 | .7 | 34.5 |

| 1993† | Chicago | 19 | 19 | 41.2 | .475 | .389 | .805 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 2.1 | .9 | 35.1 |

| 1995 | Chicago | 10 | 10 | 42.0 | .484 | .367 | .810 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 31.5 |

| 1996† | Chicago | 18 | 18 | 40.7 | .459 | .403 | .818 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 1.8 | .3 | 30.7 |

| 1997† | Chicago | 19 | 19 | 42.3 | .456 | .194 | .831 | 7.9 | 4.8 | 1.6 | .9 | 31.1 |

| 1998† | Chicago | 21 | 21 | 41.5 | .462 | .302 | .812 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 1.5 | .6 | 32.4 |

| Career[13] | 179 | 179 | 41.8 | .487 | .332 | .828 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 2.1 | .8 | 33.4 |

Awards and honors

- NBA

- Six-time NBA champion – 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998[5]

- Six-time NBA Finals MVP – 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998[13]

- Five-time NBA MVP – 1988, 1991, 1992, 1996, 1998[5]

- NBA Defensive Player of the Year – 1987–88[259]

- NBA Rookie of the Year – 1984–85[5]

- 10-time NBA scoring leader – 1987–1993, 1996–1998[13]

- Three-time NBA steals leader – 1988, 1990, 1993[13]

- 14-time NBA All-Star – 1985–1993, 1996–1998, 2002, 2003[13]

- Three-time NBA All-Star Game MVP – 1988, 1996, 1998[13]

- 10-time All-NBA First Team – 1987–1993, 1996–1998[5]

- One-time All-NBA Second Team – 1985[5]

- Nine-time NBA All-Defensive First Team – 1988–1993, 1996–1998[5]

- NBA All-Rookie First Team – 1985[13]

- Two-time NBA Slam Dunk Contest champion – 1987, 1988[5]

- Two-time IBM Award winner – 1985, 1989[259]

- Named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996[5]

- Selected on the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021[23]

- No. 23 retired by the Chicago Bulls[260]

- No. 23 retired by the Miami Heat[260]

- NBA MVP trophy renamed in Jordan’s honor («Michael Jordan Trophy») in 2022[261]

- USA Basketball

- Two-time Olympic gold medal winner – 1984, 1992[5]

- Tournament of the Americas gold medal winner – 1992[262]

- Pan American Games gold medal winner – 1983[263]

- NCAA

- NCAA national championship – 1981–82[259]

- ACC Freshman of the Year – 1981–82[264]

- Two-time Consensus NCAA All-American First Team – 1982–83, 1983–84[264]

- ACC Men’s Basketball Player of the Year – 1983–84[264]

- USBWA College Player of the Year – 1983–84[265]

- Naismith College Player of the Year – 1983–84[5]

- Adolph Rupp Trophy – 1983–84[266]

- John R. Wooden Award – 1983–84[5]

- No. 23 retired by the North Carolina Tar Heels[267]

- High school

- McDonald’s All-American – 1981[36]

- Parade All-American First Team – 1981[268]

- Halls of Fame

- Two-time Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductee:

- Class of 2009 – individual[17]

- Class of 2010 – as a member of the «Dream Team»[18]

- United States Olympic Hall of Fame – Class of 2009 (as a member of the «Dream Team»)[19]

- North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame – Class of 2010[20]

- Two-time FIBA Hall of Fame inductee:

- Class of 2015 – individual[21]

- Class of 2017 – as a member of the «Dream Team»[22]

- Media

- Three-time Associated Press Athlete of the Year – 1991, 1992, 1993[269]

- Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year – 1991[270]

- Ranked No. 1 by Slam magazine’s «Top 50 Players of All-Time»[271]

- Ranked No. 1 by ESPN SportsCentury‘s «Top North American Athletes of the 20th Century»[238]

- 10-time ESPY Award winner (in various categories)[272]

- 1997 Marca Leyenda winner[273]

- National

- 2016 Presidential Medal of Freedom[28]

- State/local

- Statue inside the United Center[274]

- Section of Madison Street in Chicago renamed Michael Jordan Drive – 1994[275]

Post-retirement

Jordan on a golf course in 2007

After his third retirement, Jordan assumed that he would be able to return to his front office position as Director of Basketball Operations with the Wizards.[276] His previous tenure in the Wizards’ front office had produced mixed results and may have also influenced the trade of Richard «Rip» Hamilton for Jerry Stackhouse, although Jordan was not technically Director of Basketball Operations in 2002.[170] On May 7, 2003, Wizards owner Abe Pollin fired Jordan as the team’s president of basketball operations.[170] Jordan later stated that he felt betrayed, and that if he had known he would be fired upon retiring, he never would have come back to play for the Wizards.[109]

Jordan kept busy over the next few years. He stayed in shape, played golf in celebrity charity tournaments, and spent time with his family in Chicago. He also promoted his Jordan Brand clothing line and rode motorcycles.[277] Since 2004, Jordan has owned Michael Jordan Motorsports, a professional closed-course motorcycle road racing team that competed with two Suzukis in the premier Superbike championship sanctioned by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) until the end of the 2013 season.[278][279]

Charlotte Bobcats/Hornets

On June 15, 2006, Jordan bought a minority stake in the Charlotte Bobcats (known as the Hornets since 2013), becoming the team’s second-largest shareholder behind majority owner Robert L. Johnson. As part of the deal, Jordan took full control over the basketball side of the operation, with the title Managing Member of Basketball Operations.[280][281] Despite Jordan’s previous success as an endorser, he has made an effort not to be included in Charlotte’s marketing campaigns.[282] A decade earlier, Jordan had made a bid to become part-owner of Charlotte’s original NBA team, the Charlotte Hornets, but talks collapsed when owner George Shinn refused to give Jordan complete control of basketball operations.[283]

In February 2010, it was reported that Jordan was seeking majority ownership of the Bobcats.[284] As February wore on, it became apparent that Jordan and former Houston Rockets president George Postolos were the leading contenders for ownership of the team. On February 27, the Bobcats announced that Johnson had reached an agreement with Jordan and his group, MJ Basketball Holdings, to buy the team from Johnson pending NBA approval.[285] On March 17, the NBA Board of Governors unanimously approved Jordan’s purchase, making him the first former player to become the majority owner of an NBA team.[286] It also made him the league’s only African-American majority owner.[287]

During the 2011 NBA lockout, The New York Times wrote that Jordan led a group of 10 to 14 hardline owners who wanted to cap the players’ share of basketball-related income at 50 percent and as low as 47. Journalists observed that, during the labor dispute in 1998, Jordan had told Washington Wizards then-owner Abe Pollin: «If you can’t make a profit, you should sell your team.»[288] Jason Whitlock of FoxSports.com called Jordan «a hypocrite sellout who can easily betray the very people who made him a billionaire global icon» for wanting «current players to pay for his incompetence».[289] He cited Jordan’s executive decisions to draft disappointing players Kwame Brown and Adam Morrison.[289]

During the 2011–12 NBA season that was shortened to 66 games by the lockout, the Bobcats posted a 7–59 record. The team closed out the season with a 23-game losing streak; their .106 winning percentage was the worst in NBA history.[290] Before the next season, Jordan said: «I’m not real happy about the record book scenario last year. It’s very, very frustrating.»[291]

During the 2019 NBA offseason, Jordan sold a minority piece of the Hornets to Gabe Plotkin and Daniel Sundheim, retaining the majority of the team for himself,[292] as well as the role of chairman.[293]

23XI Racing

On September 21, 2020, Jordan and NASCAR driver Denny Hamlin announced they would be fielding a NASCAR team with Bubba Wallace driving, beginning competition in the 2021 season. [294] On October 22, the team’s name was confirmed to be 23XI Racing (pronounced twenty-three eleven) and the team’s entry would bear No. 23.[295] As of the end of the 2022 season, 23XI Racing have 3 wins, 2 of them coming from Wallace, and 1 coming from Kurt Busch.[296]

Personal life

Jordan is the fourth of five children. He has two older brothers, Larry Jordan and James R. Jordan Jr., one older sister, Deloris, and one younger sister, Roslyn.[297][298] James retired in 2006 as the command sergeant major of the 35th Signal Brigade of the XVIII Airborne Corps in the U.S. Army.[299] Jordan’s nephew through Larry, Justin Jordan, played NCAA Division I basketball for the UNC Greensboro Spartans and is a scout for the Charlotte Hornets.[300][301]

Jordan married Juanita Vanoy on September 2, 1989, at A Little White Wedding Chapel in Las Vegas, Nevada.[302][303] They had two sons, Jeffrey and Marcus, and a daughter, Jasmine.[304] The Jordans filed for divorce on January 4, 2002, citing irreconcilable differences, but reconciled shortly thereafter. They again filed for divorce and were granted a final decree of dissolution of marriage on December 29, 2006, commenting that the decision was made «mutually and amicably».[305][306] It is reported that Juanita received a $168 million settlement (equivalent to $226 million in 2021), making it the largest celebrity divorce settlement on public record at the time.[307][308]

In 1991, Jordan purchased a lot in Highland Park, Illinois, where he planned to build a 56,000 square-foot (5,200 m2) mansion. It was completed in 1995. He listed the mansion for sale in 2012.[309] He also owns homes in North Carolina and Jupiter Island, Florida.[310] His two sons attended Loyola Academy, a private Catholic school in Wilmette, Illinois.[311] Jeffrey graduated in 2007 and played his first collegiate basketball game for the University of Illinois on November 11, 2007. After two seasons, he left the Illinois basketball team in 2009. He later rejoined the team for a third season,[312][313] then received a release to transfer to the University of Central Florida, where Marcus was attending.[314][315] Marcus transferred to Whitney Young High School after his sophomore year at Loyola Academy and graduated in 2009. He began attending UCF in the fall of 2009,[316] and played three seasons of basketball for the school.[317]

On July 21, 2006, a judge in Cook County, Illinois, determined that Jordan did not owe his alleged former lover Karla Knafel $5 million in a breach of contract claim.[318] Jordan had allegedly paid Knafel $250,000 to keep their relationship a secret.[319][320][321] Knafel claimed Jordan promised her $5 million for remaining silent and agreeing not to file a paternity suit after Knafel learned she was pregnant in 1991; a DNA test showed Jordan was not the father of the child.[318]

Jordan proposed to his longtime girlfriend, Cuban-American model Yvette Prieto, on Christmas 2011,[322] and they were married on April 27, 2013, at Bethesda-by-the-Sea Episcopal Church.[323][324] It was announced on November 30, 2013, that the two were expecting their first child together.[325][326] On February 11, 2014, Prieto gave birth to identical twin daughters named Victoria and Ysabel.[327] In 2019, Jordan became a grandfather when his daughter Jasmine gave birth to a son, whose father is professional basketball player Rakeem Christmas.[328]

Media figure and business interests

Endorsements

Jordan is one of the most marketed sports figures in history. He has been a major spokesman for such brands as Nike, Coca-Cola, Chevrolet, Gatorade, McDonald’s, Ball Park Franks, Rayovac, Wheaties, Hanes, and MCI.[329] Jordan has had a long relationship with Gatorade, appearing in over 20 commercials for the company since 1991, including the «Be Like Mike» commercials in which a song was sung by children wishing to be like Jordan.[329][330]

Nike created a signature shoe for Jordan, called the Air Jordan, in 1984.[331] One of Jordan’s more popular commercials for the shoe involved Spike Lee playing the part of Mars Blackmon. In the commercials, Lee, as Blackmon, attempted to find the source of Jordan’s abilities and became convinced that «it’s gotta be the shoes».[329] The hype and demand for the shoes even brought on a spate of «shoe-jackings» where people were robbed of their sneakers at gunpoint. Subsequently, Nike spun off the Jordan line into its own division named the «Jordan Brand». The company features an impressive list of athletes and celebrities as endorsers.[332][333] The brand has also sponsored college sports programs such as those of North Carolina, UCLA, California, Oklahoma, Florida, Georgetown, and Marquette.[334][335]

Jordan also has been associated with the Looney Tunes cartoon characters. A Nike commercial shown during 1992’s Super Bowl XXVI featured Jordan and Bugs Bunny playing basketball.[336] The Super Bowl commercial inspired the 1996 live action/animated film Space Jam, which starred Jordan and Bugs in a fictional story set during the former’s first retirement from basketball.[337] They have subsequently appeared together in several commercials for MCI.[337] Jordan also made an appearance in the music video for Michael Jackson’s «Jam» (1992).[338]

Since 2008, Jordan’s yearly income from the endorsements is estimated to be over $40 million.[339][340] In addition, when Jordan’s power at the ticket gates was at its highest point, the Bulls regularly sold out both their home and road games.[341] Due to this, Jordan set records in player salary by signing annual contracts worth in excess of US$30 million per season.[342] An academic study found that Jordan’s first NBA comeback resulted in an increase in the market capitalization of his client firms of more than $1 billion.[343]

Most of Jordan’s endorsement deals, including his first deal with Nike, were engineered by his agent, David Falk.[344] Jordan has described Falk as «the best at what he does» and that «marketing-wise, he’s great. He’s the one who came up with the concept of ‘Air Jordan.'»[345]

Business ventures

In June 2010, Jordan was ranked by Forbes as the 20th-most powerful celebrity in the world with $55 million earned between June 2009 and June 2010. According to Forbes, Jordan Brand generates $1 billion in sales for Nike.[346] In June 2014, Jordan was named the first NBA player to become a billionaire, after he increased his stake in the Charlotte Hornets from 80% to 89.5%.[347][348] On January 20, 2015, Jordan was honored with the Charlotte Business Journal’s Business Person of the Year for 2014.[349] In 2017, he became a part owner of the Miami Marlins of Major League Baseball.[350]

Forbes designated Jordan as the athlete with the highest career earnings in 2017.[351] From his Jordan Brand income and endorsements, Jordan’s 2015 income was an estimated $110 million, the most of any retired athlete.[352] As of 2022, his net worth is estimated at $1.7 billion by Forbes,[29] making him the sixth-richest African-American, behind Robert F. Smith, David Steward, Oprah Winfrey, Kanye West, and Rihanna.[353]

Jordan co-owns an automotive group which bears his name. The company has a Nissan dealership in Durham, North Carolina, acquired in 1990,[354] and formerly had a Lincoln–Mercury dealership from 1995 until its closure in June 2009.[355][356] The company also owned a Nissan franchise in Glen Burnie, Maryland.[355] The restaurant industry is another business interest of Jordan’s. Restaurants he has owned include a steakhouse in New York City’s Grand Central Terminal, among others;[357] that restaurant closed in 2018.[358] Jordan is the majority investor in a golf course, Grove XXIII, under construction in Hobe Sound, Florida.[359]

In September 2020, Jordan became an investor and advisor for DraftKings.[360]

Philanthropy

From 2001 to 2014, Jordan hosted an annual golf tournament, the Michael Jordan Celebrity Invitational, that raised money for various charities.[361] In 2006, Jordan and his wife Juanita pledged $5 million to Chicago’s Hales Franciscan High School.[362] The Jordan Brand has made donations to Habitat for Humanity and a Louisiana branch of the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.[363]

The Make-A-Wish Foundation named Jordan its Chief Wish Ambassador in 2008.[361] In 2013, he granted his 200th wish for the organization.[364] As of 2019, he has raised more than $5 million for the Make-A-Wish Foundation.[361]

In 2015, Jordan donated a settlement of undisclosed size from a lawsuit against supermarkets that had used his name without permission to 23 different Chicago charities.[365] In 2017, Jordan funded two Novant Health Michael Jordan Family Clinics in Charlotte, North Carolina, by giving $7 million, the biggest donation he had made at the time.[366] In 2018, after Hurricane Florence damaged parts of North Carolina, including his former hometown of Wilmington, Jordan donated $2 million to relief efforts.[367] He gave $1 million to aid the Bahamas’ recovery following Hurricane Dorian in 2019.[368]

On June 5, 2020, in the wake of the protests following the murder of George Floyd, Jordan and his brand announced in a joint statement that they would be donating $100 million over the next 10 years to organizations dedicated to «ensuring racial equality, social justice and greater access to education».[369] In February 2021, Jordan funded two Novant Health Michael Jordan Family Clinics in New Hanover County, North Carolina, by giving $10 million.[370][371]

Film and television

Jordan played himself in the 1996 comedy film Space Jam. The film received mixed reviews,[26] but it was a box office success, making $230 million worldwide, and earned more than $1 billion through merchandise sales.[372]

In 2000, Jordan was the subject of an IMAX documentary about his career with the Chicago Bulls, especially the 1998 NBA playoffs, entitled Michael Jordan to the Max.[373] Two decades later, the same period of Jordan’s life was covered in much greater and more personal detail by the Emmy Award-winning The Last Dance, a 10-part TV documentary which debuted on ESPN in April and May 2020. The Last Dance relied heavily on about 500 hours of candid film of Jordan’s and his teammates’ off-court activities which an NBA Entertainment crew had shot over the course of the 1997–98 NBA season for use in a documentary. The project was delayed for many years because Jordan had not yet given his permission for the footage to be used.[374][375] He was interviewed at three homes associated with the production and did not want cameras in his home or on his plane, as according to director Jason Hehir «there are certain aspects of his life that he wants to keep private».[376]

Jordan granted rapper Travis Scott permission to film a music video for his single «Franchise» at his home in Highland Park, Illinois.[377] Jordan appeared in the 2022 miniseries The Captain, which follows the life and career of Derek Jeter.[378]

Books

Jordan has authored several books focusing on his life, basketball career, and world view.

- Rare Air: Michael on Michael, with Mark Vancil and Walter Iooss (Harper San Francisco, 1993).[379][380]

- I Can’t Accept Not Trying: Michael Jordan on the Pursuit of Excellence, with Mark Vancil and Sandro Miller (Harper San Francisco, 1994).[381]

- For the Love of the Game: My Story, with Mark Vancil (Crown Publishers, 1998).[382]

- Driven from Within, with Mark Vancil (Atria Books, 2005).[383]

See also

- Forbes’ list of the world’s highest-paid athletes

- List of athletes who came out of retirement

- List of NBA teams by single season win percentage

- Michael Jordan’s Restaurant

- Michael Jordan: Chaos in the Windy City

- Michael Jordan in Flight

- NBA 2K11

- NBA 2K12

Notes

- ^ Jordan’s weight fluctuated from 195 lb (88 kg) to 218 lb (99 kg) during the course of his professional career;[1][2][3] his NBA listed weight was 216 lb (98 kg).[4][5][6]

- ^ Jordan wore a nameless No. 12 jersey in a February 14, 1990, game against the Orlando Magic because his No. 23 jersey had been stolen.[7] Jordan scored 49 points, setting a franchise record for players wearing that jersey number.[8]

References

- ^ Telander, Rick (February 14, 2018). «Michael Jordan Put on a Helluva Show at ’88 All-Star Weekend». Slam. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Quinn, Sam (May 11, 2020). «How Michael Jordan bulked up to outmuscle Pistons, win first NBA championship with Bulls». CBS Sports. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Thompson, Wright (February 22, 2013). «Michael Jordan Has Not Left the Building». ESPN The Magazine. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ «Michael Jordan Info Page». NBA. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab «Michael Jordan Bio». NBA. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ «Chicago Bulls: Historical» (PDF). NBA. p. 362. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Chris (December 12, 2012). «The greatest No. 12 that no one is talking about». USA Today. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Sam (February 15, 1990). «Magic has the Bulls’ number: Catledge leads rally; Jordan scores 49 points», Chicago Tribune, p. A1.

- ^ Rein, Kotler and Shields, p. 173.

- ^ «Legends profile: Michael Jordan». NBA.com. September 14, 2021. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Markovits and Rensman, p. 89.

- ^ «The NBA’s 75th Anniversary Team, ranked: Where 76 basketball legends check in on our list». ESPN.com. February 21, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

Jordan is widely regarded as the greatest basketball player of all time — he changed so many different facets of the league — but maybe most of all, he showed players they could grow themselves into a global brand on and off the floor with stellar play and the right marketing machine behind it all.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w «Michael Jordan Stats». Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (June 15, 1991). «Sports of The Times; Air Jordan And Just Plain Folks». The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b «American NBA players who never lost with Team USA: Jordan is second». Marca. August 9, 2021. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Weinstein, Brad, ed. (2019). 2019–20 Official NBA Guide (PDF). NBA Properties. pp. 182, 199. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Smith, Sam (September 12, 2009). «Jordan makes a Hall of Fame address». NBA.com. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Associated Press (August 14, 2010). «Scottie Pippen, Karl Malone enter Hall». ESPN. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b «Dream Team Celebrates 25th Anniversary Of Golden Olympic Run». USA Basketball, July 26, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Associated Press (December 1, 2010). «Jordan to be inducted in NC Sports Hall of Fame». Newsday. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b «Michael Jordan to be inducted into FIBA Hall of Fame». ESPN. July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ a b «2017 Class of FIBA Hall of Fame: Dream Team». FIBA. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d «Michael Jordan». NBA. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ «Michael Jordan: A Global Icon». Faze. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Skidmore, Sarah (January 10, 2008). «23 years later, Air Jordans maintain mystique». The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Braxton, Greg (May 10, 2020). «‘Drove Michael crazy’: Space Jam director on ups and downs of Jordan’s star turn». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Davis, Adam (March 7, 2016). «Michael Jordan Becomes First Billionaire NBA Player». Fox Business. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c «President Obama Names Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom». The White House. November 16, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ a b «Michael Jordan». Forbes. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Morrissey, Rick (September 10, 2009). «Chapter 1: Brooklyn». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Halberstam, p. 17.

- ^ Lazenby, p. 43.

- ^ a b Halberstam, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Poppel, Seth (October 17, 2015). «Michael Jordan Didn’t Make Varsity—At First». Newsweek. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c «Michael Jordan – High School, Amateur, and Exhibition Stats». Basketball Reference. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Williams, Lena (December 7, 2001). «Plus: Basketball; ‘A McDonald’s Game For Girls, Too'». The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ^ Lazenby, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Porter, p. 8.

- ^ a b Lazenby, p. 141.

- ^ Foreman, Tom Jr. (March 19, 1981). «Alphelia Jenkins Makes All-State». Rocky Mount Telegram. Associated Press. p. 14. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Buchalter, Bill (April 19, 1981). «14th All-Southern team grows taller, gets better». Sentinel Star. p. 8C. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Halberstam, pp. 67–68.

- ^ LaFeber, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «Michael Jordan». Database Basketball. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Hoffman, Benjamin (February 22, 2014). «Jordan Keeps Haunting Knicks’ Playoff Hopes». The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Lazenby, Roland (1999). «Michaelangelo: Portrait of a Champion». Michael Jordan: The Ultimate Career Tribute. Bannockburn, Illinois: H&S Media. p. 128.

- ^ «Michael Jordan says his title-winning shot in 1982 was ‘the birth of Michael Jordan’«. ESPN.com. April 4, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ «Michael Jordan Carolina Basketball Facts». North Carolina Tar Heels. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ «Michael Jordan». Sports Reference. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2022.