«Billy Pilgrim» redirects here. For the American folk rock duo, see Billy Pilgrim (duo).

First edition cover | |

| Author | Kurt Vonnegut |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dark comedy Satire Science fiction War novel Metafiction Postmodernism |

| Publisher | Delacorte |

| Publication date | March 31, 1969[1] |

| Pages | 190 (First Edition)[2] |

| ISBN | 0-385-31208-3 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 29960763 |

| LC Class | PS3572.O5 S6 1994 |

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life and experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain’s assistant during World War II, to the post-war years, with Billy occasionally traveling through time. The text centers on Billy’s capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience which Vonnegut himself lived through as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of «unmatched moral clarity»[3] and «one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time».[3]

Plot[edit]

The story is told in a non-linear order by an unreliable narrator (he begins the novel by telling the reader, «All of this happened, more or less»). Events become clear through flashbacks and descriptions of his time travel experiences.[4] In the first chapter, the narrator describes his writing of the book, his experiences as a University of Chicago anthropology student and a Chicago City News Bureau correspondent, his research on the Children’s Crusade and the history of Dresden, and his visit to Cold War-era Europe with his wartime friend Bernard V. O’Hare. He then writes about Billy Pilgrim, an American man from the fictional town of Ilium, New York, who believes that he was held at one time in an alien zoo on a planet he calls Tralfamadore, and that he has experienced time travel.

As a chaplain’s assistant in the United States Army during World War II, Billy is an ill-trained, disoriented, and fatalistic American soldier who discovers that he does not like war and refuses to fight.[5] He is transferred from a base in South Carolina to the front line in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge. He narrowly escapes death as the result of a string of events. He also meets Roland Weary, a patriot, warmonger, and sadistic bully who derides Billy’s cowardice. The two of them are captured in 1944 by the Germans, who confiscate all of Weary’s belongings and force him to wear wooden clogs that cut painfully into his feet; the resulting wounds become gangrenous, which eventually kills him. While Weary is dying in a rail car full of prisoners, he convinces a fellow soldier, Paul Lazzaro, that Billy is to blame for his death. Lazzaro vows to avenge Weary’s death by killing Billy, because revenge is «the sweetest thing in life».

At this exact time, Billy becomes «unstuck in time» and has flashbacks from his former and future life. Billy and the other prisoners are transported into Germany. By 1945, the prisoners have arrived in the German city of Dresden to work in «contract labor» (forced labor). The Germans hold Billy and his fellow prisoners in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-fünf («slaughterhouse five»). During the extensive bombing of Dresden by the Allies, German guards hide with the prisoners in the slaughterhouse, which is partially underground and well-protected from the damage on the surface. As a result, they are among the few survivors of the firestorm that rages in the city between February 13 and 15, 1945. After V-E Day in May 1945, Billy is transferred to the United States and receives an honorable discharge in July 1945.

Soon, Billy is hospitalized with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and placed under psychiatric care at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Lake Placid. There, he shares a room with Eliot Rosewater, who introduces Billy to the novels of an obscure science fiction author, Kilgore Trout. After his release, Billy marries Valencia Merble, whose father owns the Ilium School of Optometry that Billy later attends. Billy becomes a successful and wealthy optometrist. In 1947, Billy and Valencia conceive their first child, Robert, on their honeymoon in Cape Ann, Massachusetts. Two years later their second child, Barbara, is born. On Barbara’s wedding night, Billy is abducted by a flying saucer and taken to a planet many light-years away from Earth called Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians are described as being able to see in four dimensions, simultaneously observing all points in the space-time continuum. They universally adopt a fatalistic worldview: death means nothing to them, and their common response to hearing about death is «so it goes».

On Tralfamadore, Billy is put in a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo; the dome represents a house on Earth. The Tralfamadorians later abduct a pornographic film star named Montana Wildhack, who had disappeared on Earth and was believed to have drowned in San Pedro Bay. They intend to have her mate with Billy. She and Billy fall in love and have a child together. Billy is instantaneously sent back to Earth in a time warp to re-live past or future moments of his life.

In 1968, Billy and a co-pilot are the only survivors of a plane crash in Vermont. While driving to visit Billy in the hospital, Valencia crashes her car and dies of carbon monoxide poisoning. Billy shares a hospital room with Bertram Rumfoord, a Harvard University history professor researching an official history of the war. They discuss the bombing of Dresden, which the professor initially refuses to believe Billy witnessed; the professor claims that the bombing of Dresden was justified despite the great loss of civilian lives and the complete destruction of the city.

Billy’s daughter takes him home to Ilium. He escapes and flees to New York City. In Times Square he visits a pornographic book store, where he discovers books written by Kilgore Trout and reads them. Among the books he discovers a book entitled The Big Board, about a couple abducted by aliens and tricked into managing the aliens’ investments on Earth. He also finds a number of magazine covers noting the disappearance of Montana Wildhack, who happens to be featured in a pornographic film being shown in the store. Later in the evening, when he discusses his time travels to Tralfamadore on a radio talk show, he is ejected from the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep, and time-travels back to 1945 in Dresden. Billy and his fellow prisoners are tasked with locating and burying the dead. After a Maori New Zealand soldier working with Billy dies of dry heaves the Germans begin cremating the bodies en masse with flamethrowers. Billy’s friend Edgar Derby is shot for stealing a teapot. Eventually all of the German soldiers leave to fight on the Eastern Front, leaving Billy and the other prisoners alone with tweeting birds as the war ends.

Through non-chronological storytelling, other parts of Billy’s life are told throughout the book. After Billy is evicted from the radio studio, Barbara treats Billy as a child and often monitors him. Robert becomes starkly anti-communist, enlists as a Green Beret and fights in the Vietnam War. Billy eventually dies in 1976, at which point the United States has been partitioned into twenty separate countries and attacked by China with thermonuclear weapons. He gives a speech in a baseball stadium in Chicago in which he predicts his own death and proclaims that «if you think death is a terrible thing, then you have not understood a word I’ve said.» Billy soon after is shot with a laser gun by an assassin commissioned by the elderly Lazzaro.

Characters[edit]

- Narrator: Recurring as a minor character, the narrator seems anonymous while also clearly identifying himself as Kurt Vonnegut, when he says, «That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.»[6] As noted above, as an American soldier during World War II, Vonnegut was captured by Germans at the Battle of the Bulge and transported to Dresden. He and fellow prisoners-of-war survived the bombing while being held in a deep cellar of Schlachthof Fünf («Slaughterhouse-Five»).[7] The narrator begins the story by describing his connection to the firebombing of Dresden and his reasons for writing Slaughterhouse-Five.

- Billy Pilgrim: A fatalistic optometrist ensconced in a dull, safe marriage in Ilium, New York. During World War II, he was held as a prisoner-of-war in Dresden and survived the firebombing, experiences which had a lasting effect on his post-war life. His time travel occurs at desperate times in his life; he relives past and future events and becomes fatalistic (though not a defeatist) because he claims to have seen when, how, and why he will die.

- Roland Weary: A weak man dreaming of grandeur and obsessed with gore and vengeance, who saves Billy several times (despite Billy’s protests) in hopes of attaining military glory. He coped with his unpopularity in his home city of Pittsburgh by befriending and then beating people less well-liked than him, and is obsessed with his father’s collection of torture equipment. Weary is also a bully who beats Billy and gets them both captured, leading to the loss of his winter uniforms and boots. Weary dies of gangrene on the train en route to the POW camp, and blames Billy in his dying words.

- Paul Lazzaro: Another POW. A sickly, ill-tempered car thief from Cicero, Illinois who takes Weary’s dying words as a revenge commission to kill Billy. He keeps a mental list of his enemies, claiming he can have anyone «killed for a thousand dollars plus traveling expenses.» Lazzaro eventually fulfills his promise to Weary and has Billy assassinated by a laser gun in 1976.

- Kilgore Trout: A failed science fiction writer whose hometown is also Ilium, New York, and who makes money by managing newspaper delivery boys. He has received only one fan letter (from Eliot Rosewater; see below). After Billy meets him in a back alley in Ilium, he invites Trout to his wedding anniversary celebration. There, Kilgore follows Billy, thinking the latter has seen through a «time window.» Kilgore Trout is also a main character in Vonnegut’s 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions.

- Edgar Derby: A middle-aged high school teacher who felt that he needed to participate in the war rather than just send off his students to fight. Though relatively unimportant, he seems to be the only American before the bombing of Dresden to understand what war can do to people. During Campbell’s presentation he stands up and castigates him, defending American democracy and the alliance with the Soviet Union. German forces summarily execute him for looting after they catch him taking a teapot from catacombs after the bombing. Vonnegut has said that this death is the climax of the book as a whole.

- Howard W. Campbell Jr.: An American-born Nazi. Before the war, he lived in Germany where he was a noted German-language playwright recruited by the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. In an essay, he connects the misery of American poverty to the disheveled appearance and behavior of the American POWs. Edgar Derby confronts him when Campbell tries to recruit American POWs into the American Free Corps to fight the Communist Soviet Union on behalf of the Nazis. He appears wearing swastika-adorned cowboy hat and boots and with a red, white, and blue Nazi armband. Campbell is the protagonist of Vonnegut’s 1962 novel Mother Night.

- Valencia Merble: Billy’s wife and the mother of their children, Robert and Barbara. Billy is emotionally distant from her. She dies from carbon monoxide poisoning after an automobile accident en route to the hospital to see Billy after his airplane crash.

- Robert Pilgrim: Son of Billy and Valencia. A troubled, middle-class boy and disappointing son who becomes an alcoholic at age 16, drops out of high school, and is arrested for vandalizing a Catholic cemetery. He later so absorbs the anti-Communist worldview that he metamorphoses from suburban adolescent rebel to Green Beret sergeant. He wins a Purple Heart, Bronze Star, and Silver Star in the Vietnam War.

- Barbara Pilgrim: Daughter of Billy and Valencia. She is a «bitchy flibbertigibbet» from having had to assume the family’s leadership at the age of twenty. She has «legs like an Edwardian grand piano», marries an optometrist, and treats her widowed father as a childish invalid.

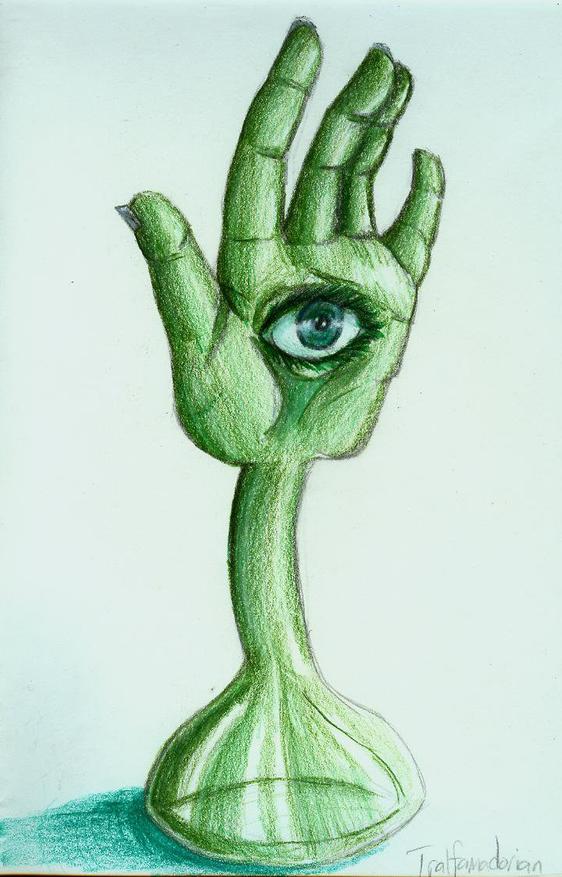

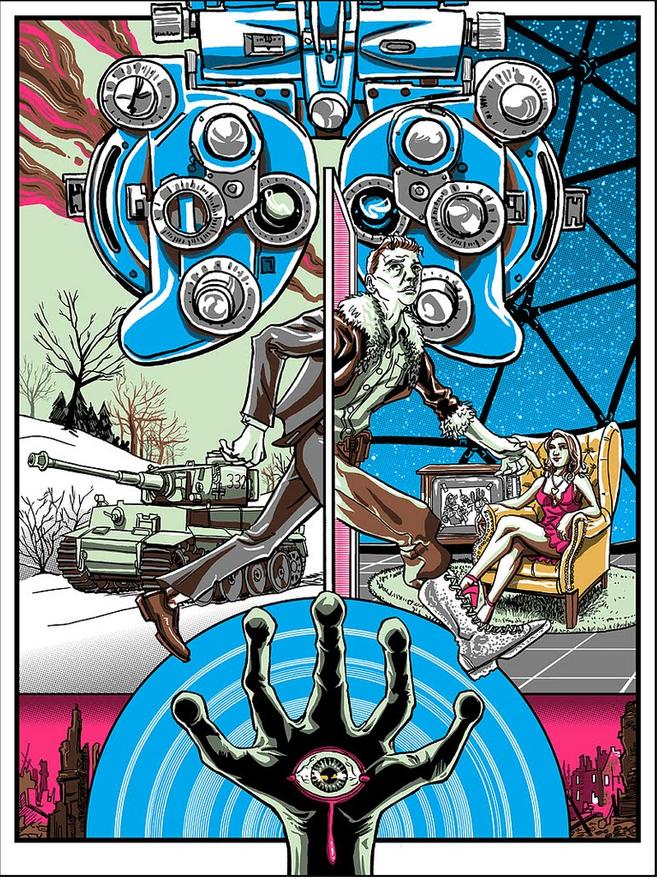

- Tralfamadorians: The race of extraterrestrial beings who appear (to humans) like upright toilet plungers with a hand atop, in which is set a single green eye. They abduct Billy and teach him about time’s relation to the world (as a fourth dimension), fate, and the nature of death. The Tralfamadorians are featured in several Vonnegut novels. In Slaughterhouse Five, they reveal that the universe will be accidentally destroyed by one of their test pilots, and there is nothing they can do about it.

- Montana Wildhack: A beautiful young model who is abducted and placed alongside Billy in the zoo on Tralfamadore. She and Billy develop an intimate relationship and they have a child. She apparently remains on Tralfamadore with the child after Billy is sent back to Earth. Billy sees her in a film showing in a pornographic book store when he stops to look at the Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. Her unexplained disappearance is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store.

- «Wild Bob»: A superannuated army officer Billy meets in the war. He tells his fellow POWs to call him «Wild Bob», as he thinks they are the 451st Infantry Regiment and under his command. He explains «If you’re ever in Cody, Wyoming, ask for Wild Bob», which is a phrase that Billy repeats to himself throughout the novel. He dies of pneumonia.

- Eliot Rosewater: Billy befriends him in the veterans’ hospital; he introduces Billy to the sci-fi novels of Kilgore Trout. Rosewater wrote the only fan letter Trout ever received. Rosewater had also suffered a terrible event during the war. Billy and Rosewater find the Trout novels helpful in dealing with the trauma of war. Rosewater is featured in other Vonnegut novels, such as God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965).

- Bertram Copeland Rumfoord: A Harvard history professor, retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, and millionaire. He shares a hospital room with Billy and is interested in the Dresden bombing. He is in the hospital after breaking his leg on his honeymoon with his fifth wife Lily, a barely literate high school drop-out and go-go girl. He is described as similar in appearance and mannerisms to Theodore Roosevelt. Bertram is likely a relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, a character in Vonnegut’s 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan.

- The Scouts: Two American infantry scouts trapped behind German lines who find Roland Weary and Billy. Roland refers to himself and the scouts as the «Three Musketeers». The scouts abandon Roland and Billy because the latter are slowing them down. They are revealed to have been shot and killed by Germans in ambush.

- Bernard V. O’Hare: The narrator’s old war friend who was also held in Dresden and accompanies him there after the war. He is the husband of Mary O’Hare, and is a district attorney from Pennsylvania.

- Mary O’Hare: The wife of Bernard V. O’Hare, to whom Vonnegut promised to name the book The Children’s Crusade. She is briefly discussed in the beginning of the book. When the narrator and Bernard try to recollect their war experiences Mary complains that they were just «babies» during the war and that the narrator will portray them as valorous men. The narrator befriends Mary by promising that he will portray them as she said and that in his book «there won’t be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne.»

- Werner Gluck: The sixteen-year-old German charged with guarding Billy and Edgar Derby when they are first placed at Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden. He does not know his way around and accidentally leads Billy and Edgar into a communal shower where some German refugee girls from Breslau are bathing. He is described as appearing similar to Billy.

Style[edit]

In keeping with Vonnegut’s signature style, the novel’s syntax and sentence structure are simple, and irony, sentimentality, black humor, and didacticism are prevalent throughout the work.[8] Like much of his oeuvre, Slaughterhouse-Five is broken into small pieces, and in this case, into brief experiences, each focused on a specific point in time. Vonnegut has noted that his books «are essentially mosaics made up of a whole bunch of tiny little chips…and each chip is a joke.» Vonnegut also includes hand-drawn illustrations in Slaughterhouse-Five, and also in his next novel, Breakfast of Champions (1973). Characteristically, Vonnegut makes heavy use of repetition, frequently using the phrase, «So it goes». He uses it as a refrain when events of death, dying, and mortality occur or are mentioned; as a narrative transition to another subject; as a memento mori; as comic relief; and to explain the unexplained. The phrase appears 106 times.[9]

The book has been categorized as a postmodern, meta-fictional novel. The first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five is written in the style of an author’s preface about how he came to write the novel. The narrator introduces the novel’s genesis by telling of his connection to the Dresden bombing, and why he is recording it. He provides a description of himself and of the book, saying that it is a desperate attempt at creating a scholarly work. He ends the first chapter by discussing the beginning and end of the novel. He then segues to the story of Billy Pilgrim: «Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time», thus the transition from the writer’s perspective to that of the third-person, omniscient narrator. (The use of «Listen» as an opening interjection has been said to mimic the opening “Hwaet!” of the medieval epic poem Beowulf.) The fictional «story» appears to begin in Chapter Two, although there is no reason to presume that the first chapter is not also fiction. This technique is common in postmodern meta-fiction.[10]

The narrator explains that Billy Pilgrim experiences his life discontinuously, so that he randomly lives (and re-lives) his birth, youth, old age, and death, rather than experiencing them in the normal linear order. There are two main narrative threads: a description of Billy’s World War II experience, which, though interrupted by episodes from other periods and places in his life, is mostly linear; and a description of his discontinuous pre-war and post-war lives. A main idea is that Billy’s existential perspective had been compromised by his having witnessed Dresden’s destruction (although he had come «unstuck in time» before arriving in Dresden).[11] Slaughterhouse-Five is told in short, declarative sentences, which create the impression that one is reading a factual report.[12]

The first sentence says, «All this happened, more or less.» (In 2010 this was ranked No. 38 on the American Book Review‘s list of «100 Best First Lines from Novels.»)[13] The opening sentences of the novel have been said to contain the aesthetic «method statement» of the entire novel.[14]

Themes[edit]

War and death[edit]

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut attempts to come to terms with war through the narrator’s eyes, Billy Pilgrim. An example within the novel, showing Vonnegut’s aim to accept his past war experiences, occurs in chapter one, when he states that «All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed all the names.»[15]

As the novel continues, it is relevant that the reality is death.[16]

Slaughterhouse-Five focuses on human imagination while interrogating the novel’s overall theme, which is the catastrophe and impact that war leaves behind.[17]

Death is something that happens fairly often in Slaughterhouse-Five. When a death occurs in the novel, Vonnegut marks the occasion with the saying «so it goes.» Bergenholtz and Clark write about what Vonnegut actually means when he uses that saying: «Presumably, readers who have not embraced Tralfamadorian determinism will be both amused and disturbed by this indiscriminate use of ‘So it goes.’ Such humor is, of course, black humor.»[18]

Religion and philosophy[edit]

Christian philosophy[edit]

Christian philosophy is present in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five but it is not very well-regarded. When God and Christianity is brought up in the work, it is mentioned in a bitter or disregarding tone. One only has to look at how the soldiers react to the mention of it. Though Billy Pilgrim had adopted some part of Christianity, he did not ascribe to all of them. JC Justus summarizes it the best when he mentions that, «‘Tralfamadorian determinism and passivity’ that Pilgrim later adopts as well as Christian fatalism wherein God himself has ordained the atrocities of war…».[19] Following Justus’s argument, Pilgrim was a character that had been through war and traveled through time. Having experienced all of these horrors in his lifetime, Pilgrim ended up adopting the Christian ideal that God had everything planned and he had given his approval for the war to happen.

Tralfamadorian philosophy[edit]

As Billy Pilgrim becomes «unstuck in time», he is faced with a new type of philosophy. When Pilgrim becomes acquainted with the Tralfamadorians, he learns a different viewpoint concerning fate and free will. While Christianity may state that fate and free will are matters of God’s divine choice and human interaction, Tralfamadorianism would disagree. According to Tralfamadorian philosophy, things are and always will be, and there is nothing that can change them. When Billy asks why they had chosen him, the Tralfamadorians reply, «Why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is.»[20] The mindset of the Tralfamadorian is not one in which free will exists. Things happen because they were always destined to be happening. The narrator of the story explains that the Tralfamadorians see time all at once. This concept of time is best explained by the Tralfamadorians themselves, as they speak to Billy Pilgrim on the matter stating, «I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is.»[21] After this particular conversation on seeing time, Billy makes the statement that this philosophy does not seem to evoke any sense of free will. To this, the Tralfamadorian reply that free will is a concept that, out of the «visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe» and «studied reports on one hundred more,» «only on Earth is there any talk of free will.”[21]

Using the Tralfamadorian passivity of fate, Billy Pilgrim learns to overlook death and the shock involved with death. Pilgrim claims the Tralfamadorian philosophy on death to be his most important lesson:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. … When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is «So it goes.»[22]

Postmodernism[edit]

The significance of postmodernism is a reoccurring theme in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel. In fact, it is said that post-modernism emerged from the modernist movement. This idea has appeared on various platforms such as music, art, fashion and film. In Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut uses postmodernism in order to challenge modernist ideas. This novel is oftentimes referred to as an «anti-war book». Vonnegut uses his personal war knowledge to unmask the real horrors behind closed doors. Postmodernism brings to light the heart-wrenching truth caused by wars. Throughout the years, postmodernists argue that the world is a meaningless place with no universal morals. Everything happens simply by chance.[15][better source needed]

Mental illness[edit]

Some have argued that Kurt Vonnegut is speaking out for veterans, many of whose post-war states are untreatable. Pilgrim’s symptoms have been identified as what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder, which didn’t exist as a term when the novel was written. In the words of one writer, «perhaps due to the fact that PTSD was not officially recognized as a mental disorder yet, the establishment fails Billy by neither providing an accurate diagnosis nor proposing any coping mechanisms.»[23] Billy found life meaningless simply because of the things that he saw in the war. War desensitized and forever changed him.[24]

Symbols[edit]

Dresden[edit]

Vonnegut was in the city of Dresden when it was bombed; he came home traumatized and unable to properly communicate the horror of what happened there. Slaughterhouse-Five is the product of the twenty years of work it took for him to communicate it in a way that satisfied him. William Allen notices this when he says, «Precisely because the story was so hard to tell, and because Vonnegut was willing to take two decades necessary to tell it – to speak the unspeakable – Slaughterhouse-Five is a great novel, a masterpiece sure to remain a permanent part of American literature.»[25] Vonnegut’s claim of a death toll of 135,000 people was based on Holocaust denier David Irving’s claim; the real number was closer to 25,000, but Vonnegut’s response was, “Does it matter?”[26] Historians claim that Vonnegut’s inflated number, and his false comparison to the Hiroshima atomic bombing propagates a false historical awareness.[27]

Food[edit]

Billy Pilgrim ended up owning «half of three Tastee-Freeze stands. Tastee-Freeze was a sort of frozen custard. It gave all the pleasure that ice cream could give, without the stiffness and bitter coldness of ice cream» (61). Throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, when Billy is eating or near food, he thinks of food in positive terms. This is partly because food is both a status symbol and comforting to people in Billy’s situation. «Food may provide nourishment, but its more important function is to soothe … Finally, food also functions as a status symbol, a sign of wealth. For instance, en route to the German prisoner-of-war camp, Billy gets a glimpse of the guards’ boxcar and is impressed by its contents … In sharp contrast, the Americans’ boxcar proclaims their dependent prisoner-of-war status.»[18]

The Bird[edit]

Throughout the novel, the bird sings «Poo-tee-weet?” After the Dresden firebombing, the bird breaks out in song. The bird also sings outside of Billy’s hospital window. The song is a symbol of a loss of words. There are no words big enough to describe a war massacre.[28]

Allusions and references[edit]

Allusions to other works[edit]

As in other novels by Vonnegut, certain characters cross over from other stories, making cameo appearances and connecting the discrete novels to a greater opus. Fictional novelist Kilgore Trout, often an important character in other Vonnegut novels, is a social commentator and a friend to Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five. In one case, he is the only non-optometrist at a party; therefore, he is the odd man out. He ridicules everything the Ideal American Family holds true, such as Heaven, Hell, and Sin. In Trout’s opinion, people do not know if the things they do turn out to be good or bad, and if they turn out to be bad, they go to Hell, where «the burning never stops hurting.» Other crossover characters are Eliot Rosewater, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Howard W. Campbell Jr., from Mother Night; and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord, relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, from The Sirens of Titan. While Vonnegut re-uses characters, the characters are frequently rebooted and do not necessarily maintain the same biographical details from appearance to appearance. Trout in particular is palpably a different person (although with distinct, consistent character traits) in each of his appearances in Vonnegut’s work.[29]

In the Twayne’s United States Authors series volume on Kurt Vonnegut, about the protagonist’s name, Stanley Schatt says:

By naming the unheroic hero Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut contrasts John Bunyan’s «Pilgrim’s Progress» with Billy’s story. As Wilfrid Sheed has pointed out, Billy’s solution to the problems of the modern world is to «invent a heaven, out of 20th century materials, where Good Technology triumphs over Bad Technology. His scripture is Science Fiction, Man’s last, good fantasy».[30]

Cultural and historical allusions[edit]

Slaughterhouse-Five makes numerous cultural, historical, geographical, and philosophical allusions. It tells of the bombing of Dresden in World War II, and refers to the Battle of the Bulge, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights protests in American cities during the 1960s. Billy’s wife, Valencia, has a «Reagan for President!» bumper sticker on her Cadillac, referring to Ronald Reagan’s failed 1968 Republican presidential nomination campaign. Another bumper sticker is mentioned, reading «Impeach Earl Warren,» referencing a real-life campaign by the far-right John Birch Society.[31][32][33]

The Serenity Prayer appears twice.[34] Critic Tony Tanner suggested that it is employed to illustrate the contrast between Billy Pilgrim’s and the Tralfamadorians’ views of fatalism.[35] Richard Hinchcliffe contends that Billy Pilgrim could be seen at first as typifying the Protestant work ethic, but he ultimately converts to evangelicalism.[36]

Reception[edit]

The reviews of Slaughterhouse-Five have been largely positive since the March 31, 1969 review in The New York Times newspaper that stated: «you’ll either love it, or push it back in the science-fiction corner.»[37] It was Vonnegut’s first novel to become a bestseller, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks and peaking at No. 4.[38] In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. It has since been widely regarded as a classic anti-war novel, and has appeared in Time magazine’s list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.[39]

Censorship controversy[edit]

Slaughterhouse-Five has been the subject of many attempts at censorship due to its irreverent tone, purportedly obscene content and depictions of sex, American soldiers’ use of profanity, and perceived heresy. It was one of the first literary acknowledgments that homosexual men, referred to in the novel as «fairies», were among the victims of the Holocaust.[40]

In the United States it has at times been banned from literature classes, removed from school libraries, and struck from literary curricula.[41] In 1972, following the ruling of Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, it was banned from Rochester Community Schools in Oakland County, Michigan.[42] The circuit judge described the book as «depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian.»[40] It was later reinstated.[43]

The U.S. Supreme Court considered the First Amendment implications of the removal of the book, among others, from public school libraries in the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) and concluded that «local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'» Slaughterhouse-Five is the sixty-seventh entry to the American Library Association’s list of the «Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999» and number forty-six on the ALA’s «Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2000–2009».[41] In August 2011, the novel was banned at the Republic High School in Missouri. The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library countered by offering 150 free copies of the novel to Republic High School students on a first-come, first-served basis.[44]

Criticism[edit]

Critics have accused Slaughterhouse-Five of being a quietist work, because Billy Pilgrim believes that the notion of free will is a quaint Earthling illusion.[45] The problem, according to Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, is that «Vonnegut’s critics seem to think that he is saying the same thing [as the Tralfamadorians].» For Anthony Burgess, «Slaughterhouse is a kind of evasion—in a sense, like J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan—in which we’re being told to carry the horror of the Dresden bombing, and everything it implies, up to a level of fantasy…» For Charles Harris, «The main idea emerging from Slaughterhouse-Five seems to be that the proper response to life is one of resigned acceptance.» For Alfred Kazin, «Vonnegut deprecates any attempt to see tragedy, that day, in Dresden…He likes to say, with arch fatalism, citing one horror after another, ‘So it goes.'» For Tanner, «Vonnegut has…total sympathy with such quietistic impulses.» The same notion is found throughout The Vonnegut Statement, a book of original essays written and collected by Vonnegut’s most loyal academic fans.[45]

When confronted with the question of how the desire to improve the world fits with the notion of time presented in Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut himself responded «you understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit.»[46]

Adaptations[edit]

- A film adaptation of the book was released in 1972. Although critically praised, the film was a box office flop. It won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a Hugo Award and Saturn Award. Vonnegut commended the film greatly. In 2013, Guillermo del Toro announced his intention to remake the 1972 film and work with a script by Charlie Kaufman.[47]

- In 1989, a theatrical adaptation was performed at the Everyman Theatre, in Liverpool, England.[48]

- In 1996, another theatrical adaptation of the novel premiered at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago. The adaptation was written and directed by Eric Simonson and featured actors Rick Snyder, Robert Breuler and Deanna Dunagan.[49] The play has subsequently been performed in several other theaters, including a New York premiere production in January 2008, by the Godlight Theatre Company. An operatic adaptation by Hans-Jürgen von Bose premiered in July 1996 at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Germany. Billy Pilgrim II was sung by Uwe Schonbeck.[50]

- In September 2009, BBC Radio 3 broadcast a feature-length radio drama based on the book, which was dramatised by Dave Sheasby, featured Andrew Scott as Billy Pilgrim and was scored by the group 65daysofstatic.[51]

- In September 2020, a graphic novel adaptation of the book, written by Ryan North and drawn by Albert Monteys, was published by BOOM! Studios, through their Archaia Entertainment imprint. It was the first time the book has been adapted into the comics medium.[52]

See also[edit]

- Four dimensionalism

References[edit]

- ^ Strodder, Chris (2007). The Encyclopedia of Sixties Cool. Santa Monica Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781595809865.

- ^ «Publication: Slaughterhouse Five». www.isfdb.org.

- ^ a b Powers, Kevin, «The Moral Clarity of ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ at 50», The New York Times, March 23, 2019, Sunday Book Review, p. 13.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. 2009 Dial Press Trade paperback edition, 2009, p. 1

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. 2009 Dial Press Trade paperback edition, 2009, p. 43

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (12 January 1999). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dial Press Trade Paperback. pp. 160. ISBN 978-0-385-33384-9.

- ^ «Slaughterhouse Five». Letters of Note. November 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ Westbrook, Perry D. «Kurt Vonnegut Jr.: Overview.» Contemporary Novelists. Susan Windisch Brown. 6th ed. New York: St. James Press, 1996.

- ^ «Slaughterhouse Five full text» (PDF). antilogicalism.com/. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ Waugh, Patricia. Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1988. p. 22.

- ^ He first time-travels while escaping from the Germans in the Ardennes forest. Exhausted, he falls asleep against a tree and experiences events from his future life.

- ^ «Kurt Vonnegut’s Fantastic Faces». Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ «100 Best First Lines from Novels». American Book Review. The University of Houston-Victoria. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Jensen, Mikkel (20 March 2016). «Janus-Headed Postmodernism: The Opening Lines of SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE». The Explicator. 74 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1080/00144940.2015.1133546. S2CID 162509316.

- ^ a b Vonnegut, Kurt (1991). SlaughterHouse-Five. New York: Dell Publishing. p. 1.

- ^ McGinnis, Wayne (1975). «The Arbitrary Cycle of Slaughterhouse-Five: A Relation of Form to Theme». Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 17 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/00111619.1975.10690101.

- ^ McGinnis, Wayne (1975). «The Arbitrary Cycle of Slaughterhouse-Five: A Relation of Form to Theme». Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 17 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/00111619.1975.10690101.

- ^ a b Bergenholtz, Rita; Clark, John R. (1998). «Food for Thought in Slaughterhouse-Five». Thalia. 18 (1): 84–93. ProQuest 214861343. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Justus, JC (2016). «About Edgar Derby: Trauma and Grief in the Unpublished Drafts of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five». Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction. 57 (5): 542–551. doi:10.1080/00111619.2016.1138445. S2CID 163412693. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children’s Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 73. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ a b Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children’s Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 82. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (1969). Slaughterhouse-Five or the Children’s Crusade. New York, New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-385-31208-0.

- ^ Czajkowska, Aleksandra (2021). ««To give form to what cannot be comprehended»: Trauma in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five and Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow» (PDF). Crossroads: A Journal of English Studies. 3 (34): 59–72. doi:10.15290/CR.2021.34.3.05. S2CID 247257373 – via The Repository of the University of Białystok.

- ^ Brown, Kevin (2011). ««The Psychiatrists Were Right: Anomic Alienation in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five»«. South Central Review. 28 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1353/scr.2011.0022. S2CID 170085340.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2009). Bloom’s Modern Interpretations: Kurt Vonnegut’s of Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 3–15. ISBN 9781604135855. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Roston, Tom (November 11, 2021). «What Early Drafts of Slaughterhouse-Five Reveal About Kurt Vonnegut’s Struggles». Time. New York, NY: Time, Inc. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Rigney, Ann (2009). «All This Happened, More or Less: What a Novelist Made of the Bombing of Dresden». History and Theory. 48 (47): 5–24. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2009.00496.x. JSTOR 25478835. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Holdefer, Charles (2017). ««Poo-tee-weet?» and Other Pastoral Questions». E-Rea. 14 (2). doi:10.4000/erea.5706.

- ^ Lerate de Castro, Jesús (30 November 1994). «The narrative function of Kilgore Trout and his fictional works in Slaughterhouse-Five». Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses (7): 115. doi:10.14198/RAEI.1994.7.09. S2CID 32180954.

- ^ Stanley Schatt, «Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Chapter 4: Vonnegut’s Dresden Novel: Slaughterhouse-Five.», In Twayne’s United States Authors Series Online. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1999 Previously published in print in 1976 by Twayne Publishers.

- ^ Vonnegut, Kurt (3 November 1991). Slaughterhouse-Five. Dell Fiction. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-440-18029-6.

- ^ Andrew Glass. «John Birch Society founded, Dec. 9, 1958». POLITICO. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- ^ Becker, Bill (1961-04-13). «WELCH, ON COAST, ATTACKS WARREN; John Birch Society Founder Outlines His Opposition to the Chief Justice». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- ^ Susan Farrell; Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work, Facts On File, 2008, Page 470.

- ^ Tanner, Tony. 1971. «The Uncertain Messenger: A Study of the Novels of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.», City of Words: American Fiction 1950-1970 (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 297-315.

- ^ Hinchcliffe, Richard (2002). ««Would’st thou be in a dream: John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five»«. European Journal of American Culture. 20 (3): 183–196(14). doi:10.1386/ejac.20.3.183.

- ^ «Books of The Times: At Last, Kurt Vonnegut’s Famous Dresden Book». New York Times. March 31, 1969. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ^ Justice, Keith (1998). Bestseller Index: all books, by author, on the lists of Publishers weekly and the New York times through 1990. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. pp. 316. ISBN 978-0786404223.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (6 January 2010). «All-TIME 100 Novels: How We Picked the List». Time.

- ^ a b Morais, Betsy (12 August 2011). «The Neverending Campaign to Ban ‘Slaughterhouse Five’«. The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ a b «100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999». American Library Association. 2013-03-27. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ «Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, 200 NW 2d 90 — Mich: Court of Appeals 1972». Archived from the original on 2019-03-25.

- ^ https://www.ftrf.org/page/History#:~:text=Todd%20v.&text=A%20grant%20was%20awarded%20to%20a%20school%20system%20in%20Rochester,from%20school%20libraries%20and%20classrooms.

- ^ Flagg, Gordon (August 9, 2011). «Vonnegut Library Fights Slaughterhouse-Five Ban with Giveaways». American Libraries. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five: The Requirements of Chaos, in Studies in American Fiction, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring, 1978, p 67.

- ^ «KURT VONNEGUT: PLAYBOY INTERVIEW (1973)». Scraps from the loft. 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ Sanjiv, Bhattacharya (10 July 2013). «Guillermo del Toro: ‘I want to make Slaughterhouse Five with Charlie Kaufman ‘«. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ «The Everyman Theatre Archive: Programmes». Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^

«Slaughterhouse-Five: September 18 — November 10, 1996″. Steppenwolf Theatre Company. 1996. Retrieved 3 October 2016. - ^

Couling, Della (19 July 1996). «Pilgrim’s progress through space». The Independent on Sunday. - ^

Sheasby, Dave (20 September 2009). «Slaughterhouse 5». BBC Radio 3. - ^

Reid, Calvin (8 January 2020). «Boom! Plans ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ Graphic Novel in 2020». Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Slaughterhouse-Five at Wikiquote- Official website

- Kurt Vonnegut discusses Slaughterhouse-Five on the BBC World Book Club

- Kilgore Trout Collection

- Photos of the first edition of Slaughterhouse-Five

- Visiting Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden

- Slaughterhous Five – Pictures of the area 65 years later

- Slaughterhouse Five digital theatre play

«Billy Pilgrim» redirects here. For the American folk rock duo, see Billy Pilgrim (duo).

First edition cover | |

| Author | Kurt Vonnegut |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dark comedy Satire Science fiction War novel Metafiction Postmodernism |

| Publisher | Delacorte |

| Publication date | March 31, 1969[1] |

| Pages | 190 (First Edition)[2] |

| ISBN | 0-385-31208-3 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 29960763 |

| LC Class | PS3572.O5 S6 1994 |

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life and experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain’s assistant during World War II, to the post-war years, with Billy occasionally traveling through time. The text centers on Billy’s capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience which Vonnegut himself lived through as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of «unmatched moral clarity»[3] and «one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time».[3]

Plot[edit]

The story is told in a non-linear order by an unreliable narrator (he begins the novel by telling the reader, «All of this happened, more or less»). Events become clear through flashbacks and descriptions of his time travel experiences.[4] In the first chapter, the narrator describes his writing of the book, his experiences as a University of Chicago anthropology student and a Chicago City News Bureau correspondent, his research on the Children’s Crusade and the history of Dresden, and his visit to Cold War-era Europe with his wartime friend Bernard V. O’Hare. He then writes about Billy Pilgrim, an American man from the fictional town of Ilium, New York, who believes that he was held at one time in an alien zoo on a planet he calls Tralfamadore, and that he has experienced time travel.

As a chaplain’s assistant in the United States Army during World War II, Billy is an ill-trained, disoriented, and fatalistic American soldier who discovers that he does not like war and refuses to fight.[5] He is transferred from a base in South Carolina to the front line in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge. He narrowly escapes death as the result of a string of events. He also meets Roland Weary, a patriot, warmonger, and sadistic bully who derides Billy’s cowardice. The two of them are captured in 1944 by the Germans, who confiscate all of Weary’s belongings and force him to wear wooden clogs that cut painfully into his feet; the resulting wounds become gangrenous, which eventually kills him. While Weary is dying in a rail car full of prisoners, he convinces a fellow soldier, Paul Lazzaro, that Billy is to blame for his death. Lazzaro vows to avenge Weary’s death by killing Billy, because revenge is «the sweetest thing in life».

At this exact time, Billy becomes «unstuck in time» and has flashbacks from his former and future life. Billy and the other prisoners are transported into Germany. By 1945, the prisoners have arrived in the German city of Dresden to work in «contract labor» (forced labor). The Germans hold Billy and his fellow prisoners in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-fünf («slaughterhouse five»). During the extensive bombing of Dresden by the Allies, German guards hide with the prisoners in the slaughterhouse, which is partially underground and well-protected from the damage on the surface. As a result, they are among the few survivors of the firestorm that rages in the city between February 13 and 15, 1945. After V-E Day in May 1945, Billy is transferred to the United States and receives an honorable discharge in July 1945.

Soon, Billy is hospitalized with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and placed under psychiatric care at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Lake Placid. There, he shares a room with Eliot Rosewater, who introduces Billy to the novels of an obscure science fiction author, Kilgore Trout. After his release, Billy marries Valencia Merble, whose father owns the Ilium School of Optometry that Billy later attends. Billy becomes a successful and wealthy optometrist. In 1947, Billy and Valencia conceive their first child, Robert, on their honeymoon in Cape Ann, Massachusetts. Two years later their second child, Barbara, is born. On Barbara’s wedding night, Billy is abducted by a flying saucer and taken to a planet many light-years away from Earth called Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians are described as being able to see in four dimensions, simultaneously observing all points in the space-time continuum. They universally adopt a fatalistic worldview: death means nothing to them, and their common response to hearing about death is «so it goes».

On Tralfamadore, Billy is put in a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo; the dome represents a house on Earth. The Tralfamadorians later abduct a pornographic film star named Montana Wildhack, who had disappeared on Earth and was believed to have drowned in San Pedro Bay. They intend to have her mate with Billy. She and Billy fall in love and have a child together. Billy is instantaneously sent back to Earth in a time warp to re-live past or future moments of his life.

In 1968, Billy and a co-pilot are the only survivors of a plane crash in Vermont. While driving to visit Billy in the hospital, Valencia crashes her car and dies of carbon monoxide poisoning. Billy shares a hospital room with Bertram Rumfoord, a Harvard University history professor researching an official history of the war. They discuss the bombing of Dresden, which the professor initially refuses to believe Billy witnessed; the professor claims that the bombing of Dresden was justified despite the great loss of civilian lives and the complete destruction of the city.

Billy’s daughter takes him home to Ilium. He escapes and flees to New York City. In Times Square he visits a pornographic book store, where he discovers books written by Kilgore Trout and reads them. Among the books he discovers a book entitled The Big Board, about a couple abducted by aliens and tricked into managing the aliens’ investments on Earth. He also finds a number of magazine covers noting the disappearance of Montana Wildhack, who happens to be featured in a pornographic film being shown in the store. Later in the evening, when he discusses his time travels to Tralfamadore on a radio talk show, he is ejected from the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep, and time-travels back to 1945 in Dresden. Billy and his fellow prisoners are tasked with locating and burying the dead. After a Maori New Zealand soldier working with Billy dies of dry heaves the Germans begin cremating the bodies en masse with flamethrowers. Billy’s friend Edgar Derby is shot for stealing a teapot. Eventually all of the German soldiers leave to fight on the Eastern Front, leaving Billy and the other prisoners alone with tweeting birds as the war ends.

Through non-chronological storytelling, other parts of Billy’s life are told throughout the book. After Billy is evicted from the radio studio, Barbara treats Billy as a child and often monitors him. Robert becomes starkly anti-communist, enlists as a Green Beret and fights in the Vietnam War. Billy eventually dies in 1976, at which point the United States has been partitioned into twenty separate countries and attacked by China with thermonuclear weapons. He gives a speech in a baseball stadium in Chicago in which he predicts his own death and proclaims that «if you think death is a terrible thing, then you have not understood a word I’ve said.» Billy soon after is shot with a laser gun by an assassin commissioned by the elderly Lazzaro.

Characters[edit]

- Narrator: Recurring as a minor character, the narrator seems anonymous while also clearly identifying himself as Kurt Vonnegut, when he says, «That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.»[6] As noted above, as an American soldier during World War II, Vonnegut was captured by Germans at the Battle of the Bulge and transported to Dresden. He and fellow prisoners-of-war survived the bombing while being held in a deep cellar of Schlachthof Fünf («Slaughterhouse-Five»).[7] The narrator begins the story by describing his connection to the firebombing of Dresden and his reasons for writing Slaughterhouse-Five.

- Billy Pilgrim: A fatalistic optometrist ensconced in a dull, safe marriage in Ilium, New York. During World War II, he was held as a prisoner-of-war in Dresden and survived the firebombing, experiences which had a lasting effect on his post-war life. His time travel occurs at desperate times in his life; he relives past and future events and becomes fatalistic (though not a defeatist) because he claims to have seen when, how, and why he will die.

- Roland Weary: A weak man dreaming of grandeur and obsessed with gore and vengeance, who saves Billy several times (despite Billy’s protests) in hopes of attaining military glory. He coped with his unpopularity in his home city of Pittsburgh by befriending and then beating people less well-liked than him, and is obsessed with his father’s collection of torture equipment. Weary is also a bully who beats Billy and gets them both captured, leading to the loss of his winter uniforms and boots. Weary dies of gangrene on the train en route to the POW camp, and blames Billy in his dying words.

- Paul Lazzaro: Another POW. A sickly, ill-tempered car thief from Cicero, Illinois who takes Weary’s dying words as a revenge commission to kill Billy. He keeps a mental list of his enemies, claiming he can have anyone «killed for a thousand dollars plus traveling expenses.» Lazzaro eventually fulfills his promise to Weary and has Billy assassinated by a laser gun in 1976.

- Kilgore Trout: A failed science fiction writer whose hometown is also Ilium, New York, and who makes money by managing newspaper delivery boys. He has received only one fan letter (from Eliot Rosewater; see below). After Billy meets him in a back alley in Ilium, he invites Trout to his wedding anniversary celebration. There, Kilgore follows Billy, thinking the latter has seen through a «time window.» Kilgore Trout is also a main character in Vonnegut’s 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions.

- Edgar Derby: A middle-aged high school teacher who felt that he needed to participate in the war rather than just send off his students to fight. Though relatively unimportant, he seems to be the only American before the bombing of Dresden to understand what war can do to people. During Campbell’s presentation he stands up and castigates him, defending American democracy and the alliance with the Soviet Union. German forces summarily execute him for looting after they catch him taking a teapot from catacombs after the bombing. Vonnegut has said that this death is the climax of the book as a whole.

- Howard W. Campbell Jr.: An American-born Nazi. Before the war, he lived in Germany where he was a noted German-language playwright recruited by the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. In an essay, he connects the misery of American poverty to the disheveled appearance and behavior of the American POWs. Edgar Derby confronts him when Campbell tries to recruit American POWs into the American Free Corps to fight the Communist Soviet Union on behalf of the Nazis. He appears wearing swastika-adorned cowboy hat and boots and with a red, white, and blue Nazi armband. Campbell is the protagonist of Vonnegut’s 1962 novel Mother Night.

- Valencia Merble: Billy’s wife and the mother of their children, Robert and Barbara. Billy is emotionally distant from her. She dies from carbon monoxide poisoning after an automobile accident en route to the hospital to see Billy after his airplane crash.

- Robert Pilgrim: Son of Billy and Valencia. A troubled, middle-class boy and disappointing son who becomes an alcoholic at age 16, drops out of high school, and is arrested for vandalizing a Catholic cemetery. He later so absorbs the anti-Communist worldview that he metamorphoses from suburban adolescent rebel to Green Beret sergeant. He wins a Purple Heart, Bronze Star, and Silver Star in the Vietnam War.

- Barbara Pilgrim: Daughter of Billy and Valencia. She is a «bitchy flibbertigibbet» from having had to assume the family’s leadership at the age of twenty. She has «legs like an Edwardian grand piano», marries an optometrist, and treats her widowed father as a childish invalid.

- Tralfamadorians: The race of extraterrestrial beings who appear (to humans) like upright toilet plungers with a hand atop, in which is set a single green eye. They abduct Billy and teach him about time’s relation to the world (as a fourth dimension), fate, and the nature of death. The Tralfamadorians are featured in several Vonnegut novels. In Slaughterhouse Five, they reveal that the universe will be accidentally destroyed by one of their test pilots, and there is nothing they can do about it.

- Montana Wildhack: A beautiful young model who is abducted and placed alongside Billy in the zoo on Tralfamadore. She and Billy develop an intimate relationship and they have a child. She apparently remains on Tralfamadore with the child after Billy is sent back to Earth. Billy sees her in a film showing in a pornographic book store when he stops to look at the Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. Her unexplained disappearance is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store.

- «Wild Bob»: A superannuated army officer Billy meets in the war. He tells his fellow POWs to call him «Wild Bob», as he thinks they are the 451st Infantry Regiment and under his command. He explains «If you’re ever in Cody, Wyoming, ask for Wild Bob», which is a phrase that Billy repeats to himself throughout the novel. He dies of pneumonia.

- Eliot Rosewater: Billy befriends him in the veterans’ hospital; he introduces Billy to the sci-fi novels of Kilgore Trout. Rosewater wrote the only fan letter Trout ever received. Rosewater had also suffered a terrible event during the war. Billy and Rosewater find the Trout novels helpful in dealing with the trauma of war. Rosewater is featured in other Vonnegut novels, such as God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965).

- Bertram Copeland Rumfoord: A Harvard history professor, retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, and millionaire. He shares a hospital room with Billy and is interested in the Dresden bombing. He is in the hospital after breaking his leg on his honeymoon with his fifth wife Lily, a barely literate high school drop-out and go-go girl. He is described as similar in appearance and mannerisms to Theodore Roosevelt. Bertram is likely a relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, a character in Vonnegut’s 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan.

- The Scouts: Two American infantry scouts trapped behind German lines who find Roland Weary and Billy. Roland refers to himself and the scouts as the «Three Musketeers». The scouts abandon Roland and Billy because the latter are slowing them down. They are revealed to have been shot and killed by Germans in ambush.

- Bernard V. O’Hare: The narrator’s old war friend who was also held in Dresden and accompanies him there after the war. He is the husband of Mary O’Hare, and is a district attorney from Pennsylvania.

- Mary O’Hare: The wife of Bernard V. O’Hare, to whom Vonnegut promised to name the book The Children’s Crusade. She is briefly discussed in the beginning of the book. When the narrator and Bernard try to recollect their war experiences Mary complains that they were just «babies» during the war and that the narrator will portray them as valorous men. The narrator befriends Mary by promising that he will portray them as she said and that in his book «there won’t be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne.»

- Werner Gluck: The sixteen-year-old German charged with guarding Billy and Edgar Derby when they are first placed at Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden. He does not know his way around and accidentally leads Billy and Edgar into a communal shower where some German refugee girls from Breslau are bathing. He is described as appearing similar to Billy.

Style[edit]

In keeping with Vonnegut’s signature style, the novel’s syntax and sentence structure are simple, and irony, sentimentality, black humor, and didacticism are prevalent throughout the work.[8] Like much of his oeuvre, Slaughterhouse-Five is broken into small pieces, and in this case, into brief experiences, each focused on a specific point in time. Vonnegut has noted that his books «are essentially mosaics made up of a whole bunch of tiny little chips…and each chip is a joke.» Vonnegut also includes hand-drawn illustrations in Slaughterhouse-Five, and also in his next novel, Breakfast of Champions (1973). Characteristically, Vonnegut makes heavy use of repetition, frequently using the phrase, «So it goes». He uses it as a refrain when events of death, dying, and mortality occur or are mentioned; as a narrative transition to another subject; as a memento mori; as comic relief; and to explain the unexplained. The phrase appears 106 times.[9]

The book has been categorized as a postmodern, meta-fictional novel. The first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five is written in the style of an author’s preface about how he came to write the novel. The narrator introduces the novel’s genesis by telling of his connection to the Dresden bombing, and why he is recording it. He provides a description of himself and of the book, saying that it is a desperate attempt at creating a scholarly work. He ends the first chapter by discussing the beginning and end of the novel. He then segues to the story of Billy Pilgrim: «Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time», thus the transition from the writer’s perspective to that of the third-person, omniscient narrator. (The use of «Listen» as an opening interjection has been said to mimic the opening “Hwaet!” of the medieval epic poem Beowulf.) The fictional «story» appears to begin in Chapter Two, although there is no reason to presume that the first chapter is not also fiction. This technique is common in postmodern meta-fiction.[10]

The narrator explains that Billy Pilgrim experiences his life discontinuously, so that he randomly lives (and re-lives) his birth, youth, old age, and death, rather than experiencing them in the normal linear order. There are two main narrative threads: a description of Billy’s World War II experience, which, though interrupted by episodes from other periods and places in his life, is mostly linear; and a description of his discontinuous pre-war and post-war lives. A main idea is that Billy’s existential perspective had been compromised by his having witnessed Dresden’s destruction (although he had come «unstuck in time» before arriving in Dresden).[11] Slaughterhouse-Five is told in short, declarative sentences, which create the impression that one is reading a factual report.[12]

The first sentence says, «All this happened, more or less.» (In 2010 this was ranked No. 38 on the American Book Review‘s list of «100 Best First Lines from Novels.»)[13] The opening sentences of the novel have been said to contain the aesthetic «method statement» of the entire novel.[14]

Themes[edit]

War and death[edit]

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut attempts to come to terms with war through the narrator’s eyes, Billy Pilgrim. An example within the novel, showing Vonnegut’s aim to accept his past war experiences, occurs in chapter one, when he states that «All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed all the names.»[15]

As the novel continues, it is relevant that the reality is death.[16]

Slaughterhouse-Five focuses on human imagination while interrogating the novel’s overall theme, which is the catastrophe and impact that war leaves behind.[17]

Death is something that happens fairly often in Slaughterhouse-Five. When a death occurs in the novel, Vonnegut marks the occasion with the saying «so it goes.» Bergenholtz and Clark write about what Vonnegut actually means when he uses that saying: «Presumably, readers who have not embraced Tralfamadorian determinism will be both amused and disturbed by this indiscriminate use of ‘So it goes.’ Such humor is, of course, black humor.»[18]

Religion and philosophy[edit]

Christian philosophy[edit]

Christian philosophy is present in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five but it is not very well-regarded. When God and Christianity is brought up in the work, it is mentioned in a bitter or disregarding tone. One only has to look at how the soldiers react to the mention of it. Though Billy Pilgrim had adopted some part of Christianity, he did not ascribe to all of them. JC Justus summarizes it the best when he mentions that, «‘Tralfamadorian determinism and passivity’ that Pilgrim later adopts as well as Christian fatalism wherein God himself has ordained the atrocities of war…».[19] Following Justus’s argument, Pilgrim was a character that had been through war and traveled through time. Having experienced all of these horrors in his lifetime, Pilgrim ended up adopting the Christian ideal that God had everything planned and he had given his approval for the war to happen.

Tralfamadorian philosophy[edit]

As Billy Pilgrim becomes «unstuck in time», he is faced with a new type of philosophy. When Pilgrim becomes acquainted with the Tralfamadorians, he learns a different viewpoint concerning fate and free will. While Christianity may state that fate and free will are matters of God’s divine choice and human interaction, Tralfamadorianism would disagree. According to Tralfamadorian philosophy, things are and always will be, and there is nothing that can change them. When Billy asks why they had chosen him, the Tralfamadorians reply, «Why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is.»[20] The mindset of the Tralfamadorian is not one in which free will exists. Things happen because they were always destined to be happening. The narrator of the story explains that the Tralfamadorians see time all at once. This concept of time is best explained by the Tralfamadorians themselves, as they speak to Billy Pilgrim on the matter stating, «I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is.»[21] After this particular conversation on seeing time, Billy makes the statement that this philosophy does not seem to evoke any sense of free will. To this, the Tralfamadorian reply that free will is a concept that, out of the «visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe» and «studied reports on one hundred more,» «only on Earth is there any talk of free will.”[21]

Using the Tralfamadorian passivity of fate, Billy Pilgrim learns to overlook death and the shock involved with death. Pilgrim claims the Tralfamadorian philosophy on death to be his most important lesson:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. … When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is «So it goes.»[22]

Postmodernism[edit]

The significance of postmodernism is a reoccurring theme in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel. In fact, it is said that post-modernism emerged from the modernist movement. This idea has appeared on various platforms such as music, art, fashion and film. In Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut uses postmodernism in order to challenge modernist ideas. This novel is oftentimes referred to as an «anti-war book». Vonnegut uses his personal war knowledge to unmask the real horrors behind closed doors. Postmodernism brings to light the heart-wrenching truth caused by wars. Throughout the years, postmodernists argue that the world is a meaningless place with no universal morals. Everything happens simply by chance.[15][better source needed]

Mental illness[edit]

Some have argued that Kurt Vonnegut is speaking out for veterans, many of whose post-war states are untreatable. Pilgrim’s symptoms have been identified as what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder, which didn’t exist as a term when the novel was written. In the words of one writer, «perhaps due to the fact that PTSD was not officially recognized as a mental disorder yet, the establishment fails Billy by neither providing an accurate diagnosis nor proposing any coping mechanisms.»[23] Billy found life meaningless simply because of the things that he saw in the war. War desensitized and forever changed him.[24]

Symbols[edit]

Dresden[edit]

Vonnegut was in the city of Dresden when it was bombed; he came home traumatized and unable to properly communicate the horror of what happened there. Slaughterhouse-Five is the product of the twenty years of work it took for him to communicate it in a way that satisfied him. William Allen notices this when he says, «Precisely because the story was so hard to tell, and because Vonnegut was willing to take two decades necessary to tell it – to speak the unspeakable – Slaughterhouse-Five is a great novel, a masterpiece sure to remain a permanent part of American literature.»[25] Vonnegut’s claim of a death toll of 135,000 people was based on Holocaust denier David Irving’s claim; the real number was closer to 25,000, but Vonnegut’s response was, “Does it matter?”[26] Historians claim that Vonnegut’s inflated number, and his false comparison to the Hiroshima atomic bombing propagates a false historical awareness.[27]

Food[edit]

Billy Pilgrim ended up owning «half of three Tastee-Freeze stands. Tastee-Freeze was a sort of frozen custard. It gave all the pleasure that ice cream could give, without the stiffness and bitter coldness of ice cream» (61). Throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, when Billy is eating or near food, he thinks of food in positive terms. This is partly because food is both a status symbol and comforting to people in Billy’s situation. «Food may provide nourishment, but its more important function is to soothe … Finally, food also functions as a status symbol, a sign of wealth. For instance, en route to the German prisoner-of-war camp, Billy gets a glimpse of the guards’ boxcar and is impressed by its contents … In sharp contrast, the Americans’ boxcar proclaims their dependent prisoner-of-war status.»[18]

The Bird[edit]

Throughout the novel, the bird sings «Poo-tee-weet?” After the Dresden firebombing, the bird breaks out in song. The bird also sings outside of Billy’s hospital window. The song is a symbol of a loss of words. There are no words big enough to describe a war massacre.[28]

Allusions and references[edit]

Allusions to other works[edit]

As in other novels by Vonnegut, certain characters cross over from other stories, making cameo appearances and connecting the discrete novels to a greater opus. Fictional novelist Kilgore Trout, often an important character in other Vonnegut novels, is a social commentator and a friend to Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five. In one case, he is the only non-optometrist at a party; therefore, he is the odd man out. He ridicules everything the Ideal American Family holds true, such as Heaven, Hell, and Sin. In Trout’s opinion, people do not know if the things they do turn out to be good or bad, and if they turn out to be bad, they go to Hell, where «the burning never stops hurting.» Other crossover characters are Eliot Rosewater, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Howard W. Campbell Jr., from Mother Night; and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord, relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, from The Sirens of Titan. While Vonnegut re-uses characters, the characters are frequently rebooted and do not necessarily maintain the same biographical details from appearance to appearance. Trout in particular is palpably a different person (although with distinct, consistent character traits) in each of his appearances in Vonnegut’s work.[29]

In the Twayne’s United States Authors series volume on Kurt Vonnegut, about the protagonist’s name, Stanley Schatt says:

By naming the unheroic hero Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut contrasts John Bunyan’s «Pilgrim’s Progress» with Billy’s story. As Wilfrid Sheed has pointed out, Billy’s solution to the problems of the modern world is to «invent a heaven, out of 20th century materials, where Good Technology triumphs over Bad Technology. His scripture is Science Fiction, Man’s last, good fantasy».[30]

Cultural and historical allusions[edit]

Slaughterhouse-Five makes numerous cultural, historical, geographical, and philosophical allusions. It tells of the bombing of Dresden in World War II, and refers to the Battle of the Bulge, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights protests in American cities during the 1960s. Billy’s wife, Valencia, has a «Reagan for President!» bumper sticker on her Cadillac, referring to Ronald Reagan’s failed 1968 Republican presidential nomination campaign. Another bumper sticker is mentioned, reading «Impeach Earl Warren,» referencing a real-life campaign by the far-right John Birch Society.[31][32][33]

The Serenity Prayer appears twice.[34] Critic Tony Tanner suggested that it is employed to illustrate the contrast between Billy Pilgrim’s and the Tralfamadorians’ views of fatalism.[35] Richard Hinchcliffe contends that Billy Pilgrim could be seen at first as typifying the Protestant work ethic, but he ultimately converts to evangelicalism.[36]

Reception[edit]

The reviews of Slaughterhouse-Five have been largely positive since the March 31, 1969 review in The New York Times newspaper that stated: «you’ll either love it, or push it back in the science-fiction corner.»[37] It was Vonnegut’s first novel to become a bestseller, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks and peaking at No. 4.[38] In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. It has since been widely regarded as a classic anti-war novel, and has appeared in Time magazine’s list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.[39]

Censorship controversy[edit]

Slaughterhouse-Five has been the subject of many attempts at censorship due to its irreverent tone, purportedly obscene content and depictions of sex, American soldiers’ use of profanity, and perceived heresy. It was one of the first literary acknowledgments that homosexual men, referred to in the novel as «fairies», were among the victims of the Holocaust.[40]

In the United States it has at times been banned from literature classes, removed from school libraries, and struck from literary curricula.[41] In 1972, following the ruling of Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, it was banned from Rochester Community Schools in Oakland County, Michigan.[42] The circuit judge described the book as «depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian.»[40] It was later reinstated.[43]

The U.S. Supreme Court considered the First Amendment implications of the removal of the book, among others, from public school libraries in the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) and concluded that «local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'» Slaughterhouse-Five is the sixty-seventh entry to the American Library Association’s list of the «Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999» and number forty-six on the ALA’s «Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2000–2009».[41] In August 2011, the novel was banned at the Republic High School in Missouri. The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library countered by offering 150 free copies of the novel to Republic High School students on a first-come, first-served basis.[44]

Criticism[edit]

Critics have accused Slaughterhouse-Five of being a quietist work, because Billy Pilgrim believes that the notion of free will is a quaint Earthling illusion.[45] The problem, according to Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, is that «Vonnegut’s critics seem to think that he is saying the same thing [as the Tralfamadorians].» For Anthony Burgess, «Slaughterhouse is a kind of evasion—in a sense, like J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan—in which we’re being told to carry the horror of the Dresden bombing, and everything it implies, up to a level of fantasy…» For Charles Harris, «The main idea emerging from Slaughterhouse-Five seems to be that the proper response to life is one of resigned acceptance.» For Alfred Kazin, «Vonnegut deprecates any attempt to see tragedy, that day, in Dresden…He likes to say, with arch fatalism, citing one horror after another, ‘So it goes.'» For Tanner, «Vonnegut has…total sympathy with such quietistic impulses.» The same notion is found throughout The Vonnegut Statement, a book of original essays written and collected by Vonnegut’s most loyal academic fans.[45]

When confronted with the question of how the desire to improve the world fits with the notion of time presented in Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut himself responded «you understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit.»[46]

Adaptations[edit]

- A film adaptation of the book was released in 1972. Although critically praised, the film was a box office flop. It won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a Hugo Award and Saturn Award. Vonnegut commended the film greatly. In 2013, Guillermo del Toro announced his intention to remake the 1972 film and work with a script by Charlie Kaufman.[47]

- In 1989, a theatrical adaptation was performed at the Everyman Theatre, in Liverpool, England.[48]