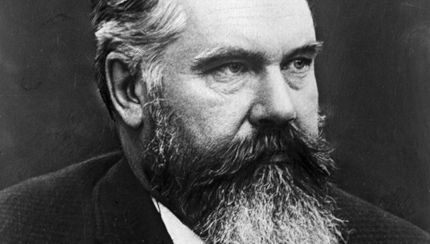

Rachmaninoff in the early 1900s

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18, is a concerto for piano and orchestra composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff between June 1900 and April 1901. From the summer to the autumn of 1900, he worked on the second and third movements of the concerto, with the first movement causing him difficulties. Both movements of the unfinished concerto were first performed with him as soloist and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] 1900. The first movement was finished in 1901 and the complete work had an astoundingly successful premiere on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1901, again with the composer as soloist and Siloti conducting. Gutheil published the work the same year. The piece established Rachmaninoff’s fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.

After the disastrous 1897 premiere of his First Symphony, Rachmaninoff suffered a psychological breakdown that prevented composition for three years. Although depression sapped his energy, he still engaged in performance. Conducting and piano lessons became necessary to ease his financial position. In 1899, he was supposed to perform the Second Piano Concerto in London, which he had not composed yet due to illness, and instead made a successful conducting debut. The success led to an invitation to return next year with his First Piano Concerto; however, he promised to reappear with a newer and better one. Rachmaninoff was later invited to Leo Tolstoy’s home in hopes of having his writer’s block revoked, but the meeting only worsened his situation. Relatives decided to introduce him to the neurologist Nikolai Dahl, whom he visited daily from January to April 1900, which helped restore his health and confidence in composition. Rachmaninoff dedicated the concerto to Dahl for successfully treating him.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

Sergei Rachmaninoff had been working on his First Symphony from January to September 1895.[1][2] In 1896, after a long hiatus, the music publisher and philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev agreed to include it at one of his Saint Petersburg Russian Symphony Concerts. However, there were setbacks: complaints were raised about the symphony by his teacher Sergei Taneyev upon receiving its score, which elicited revisions by Rachmaninoff, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov expressed dissatisfaction during rehearsal.[3][4] Eventually, the symphony was scheduled to be premiered in March 1897.[5] Before the due date, he was nervous but optimistic due to his prior successes, which included winning the Moscow Conservatory Great Gold Medal and earning the praise of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[6] The premiere, however, was a disaster; Rachmaninoff listened to the cacophonous performance backstage to avoid getting humiliated by the audience and eventually left the hall when the piece finished.[7] The symphony was brutally panned by critics,[8] and apart from issues with the piece, the poor performance of the possibly drunk conductor, Alexander Glazunov, was also to blame.[9][note 1] César Cui wrote:

If there were a conservatoire in Hell, if one of its talented students were instructed to write a programme symphony on «The Seven Plagues of Egypt», and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr Rachmaninoff’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and delighted the inmates of Hell.[note 2]

Rachmaninoff initially remained aloof to the failure of his symphony, but upon reflection, suffered a psychological breakdown that stopped his compositional output for three years.[13] He adopted a lifestyle of heavy drinking to forget about his problems.[14] Depression consumed him,[15] and although he rarely composed, he still engaged in performance, accepting a conducting position by the Russian entrepreneur Savva Mamontov at the Moscow Private Russian Opera from 1897 to 1898.[16] It provided income for the cash-strapped Rachmaninoff; he eventually left as it didn’t allow time for other activities and due to the incompetence of the theater, which turned piano lessons into his main source of income.[17][18]

At the end of 1898, Rachmaninoff was invited to perform in London in April 1899, where he was expected to play his Second Piano Concerto. However, he wrote to the London Philharmonic Society that he couldn’t finish a second concerto due to illness.[19][note 3] The society then requested he play his First Piano Concerto, but he declined, dismissing it as a student piece. Instead, he offered to conduct one of his orchestral pieces, to which the society agreed, provided he also performed at the piano. He made a successful conducting debut, performing The Rock and playing piano pieces such as his hackneyed Prelude in C-sharp minor.[21] The society secretary Francesco Berger invited him to return next year with a performance of the First Concerto. However, he promised to return with a newer and better one,[22][23] although he did not perform it there until 1908.[24] Alexander Goldenweiser, a peer from the same conservatory, wanted to play his new concerto at a Belyayev concert in Saint Petersburg, thinking its consummation was inevitable.[17] Rachmaninoff, who had thoughts of composing it three years earlier, sent a letter to him stating that nothing had been penned so far.[25]

For the rest of the summer and autumn of 1899, Rachmaninoff’s unproductiveness worsened his depression.[26] A friend of the Satins (relatives of Rachmaninoff[27]), in an attempt to revoke the depressed composer’s writer’s block, suggested he visit Leo Tolstoy.[28][note 4] However, his visit to the querulous author only served to increase his despondency, and he became so self-critical that he was rendered unable to compose.[30] The Satins, anxious about his well-being, persuaded him to visit Nikolai Dahl, a neurologist who specialized in hypnosis, with whom they had a good experience. Desperate, he agreed without hesitation.[31] From January to April 1900, he visited him daily free of charge. Dahl restored Rachmaninoff’s health as well as his confidence to compose. Himself a musician, Dahl engaged in lengthy conversations surrounding music with Rachmaninoff, and would repeat a triptych formula while the composer was half-asleep: «You will begin to write your concerto … You will work with great facility … The concerto will be of an excellent quality».[32][33] Even though the results were not readily evident, they were still successful.[34]

Composition and premiere[edit]

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform Mefistofele in La Scala, Feodor Chaliapin invited Rachmaninoff to live with him in Italy, where he sought his advice while studying the opera. During his stay, Rachmaninoff composed the love duet of his opera Francesca da Rimini and also began working on the second and third movements of his Second Piano Concerto.[35] With newfound enthusiasm for composition, he resumed working on them after returning to Russia,[35] which for the rest of the summer and the autumn were being finished «quickly and easily», although the first movement caused him difficulties.[36][note 5] He told his biographer Oscar von Riesemann that «the material grew in bulk, and new musical ideas began to stir within me—far more than I needed for my concerto».[note 6] The two finished movements were to be performed in the Moscow Nobility Hall on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] at a concert arranged for the benefit of the Ladies’ Charity Prison Committee.[39] On the eve of the concert, Rachmaninoff caught a cold, prompting his friends and relatives to stuff him with remedies, filling him with an excess of mulled wine;[40][41] he didn’t want to admit his desire to cancel the performance.[40] With him as soloist with an orchestra after an eight-year hiatus and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut, it was an anxious event, but the concert was a great success,[38] easing the worries of his close ones.[40] Ivan Lipaev wrote: «it’s been long since the walls of the Nobility Hall reverberated with such enthusiastic, storming applause as on that evening … This work contains much poetry, beauty, warmth, rich orchestration, healthy and buoyant creative power. Rachmaninoff’s talent is evident throughout.»[42] The German company Gutheil published the concerto as opus number 18 the following year.[38][note 7]

Before continuing composition, Rachmaninoff received financial aid from Siloti to tide him over for the next three years, securing his ability to compose without worrying about rent.[44] By April 1901, while staying with Goldenweiser, he finished the first movement of the concerto and subsequently premiered the full work at a Moscow Philharmonic Society concert on 9 November [O.S. 27 October], again with him at the piano and Siloti conducting.[36][45] Five days before the premiere, however, Rachmaninoff received a letter from Nikita Morozov (his Conservatory colleague[46]) pestering him regarding the structure of the concerto after receiving its score, commenting that the first subject seemed like an introduction to the second one. Frantic, he replied, writing that he concurred with his opinion and was pondering over the first movement. Regardless, it was an astounding success, and Rachmaninoff enjoyed wild acclaim.[47][48] Even Cui, who previously scolded his First Symphony, displayed exuberance over the work in a letter from 1903.[49] The piece established Rachmaninoff’s fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.[50] He dedicated it to Dahl for his treatment.[51]

Subsequent performances[edit]

The popularity of the Second Piano Concerto grew rapidly, developing global fame after its subsequent performances.[52] Its international progress started with a performance in Germany, where Siloti played it with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Arthur Nikisch’s baton in January 1902.[44] In March, the same duo had a tremendously successful performance in Saint Petersburg;[53] two days preceding this, the Rachmaninoff-Siloti duo performed back in Moscow, with the former conducting and the latter as soloist.[54] May of the same year saw a performance at the Queen’s Hall in London, the soloist being Wassily Sapellnikoff with the Philharmonic Society and Frederic Cowen conducting; London would wait until 1908 for Rachmaninoff to perform it there.[55] «One was quickly persuaded of its genuine excellence and originality», The Guardian wrote of the concerto following the performance.[56] England, however, had already heard the work twice prior to the London premiere, with performances by Siloti in Birmingham and Manchester.[57] Rachmaninoff—enhanced by success from repossessing the ability to compose again, coupled with no more financial worries—repaid the loan from Siloti within one year of receiving the last installment.[54]

After marrying his first cousin Natalia Satina, the newly-wed Rachmaninoff received an invitation to play his concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic under the direction of Vasily Safonov in December. Although the engagement guaranteed him a hefty fee, he was anxious that accepting it would show ingratitude towards Siloti.[58] However, after seeking his help, Taneyev reassured Rachmaninoff that this did not offend Siloti.[59][60] That was followed by concerts in both Vienna and Prague the following spring in 1903 under the same engagement.[61] In late 1904, Rachmaninoff won the Glinka Awards, cash prizes established in Belyayev’s will, receiving 500 rubles for his concerto.[62] Throughout his life, Rachmaninoff soloed the concerto a total of 145 times.[63]

Early reception[edit]

After he fulfilled his 1908 London concert engagement at the Queen’s Hall under Serge Koussevitzky,[64] a flattering review by The Times emerged: «The direct expression of the work, the extraordinary precision and exactitude of Rachmaninoff’s playing, and even the strict economy of movement of arms and hands which he exercises, all contributed to the impression of completeness of performance.»[65]

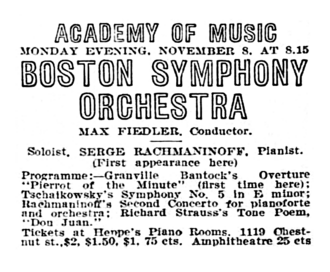

An advertisement for Rachmaninoff’s debut with an American orchestra at the Philadelphia Academy of Music, where he gave the US premiere of his concerto.

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the Philadelphia Academy of Music with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Max Fiedler’s baton, including repeat performances in Baltimore and New York City.[66] Critics since the first performance were chiefly dismissive, echoing Philip Hale’s program notes for the debut stating that «The concerto is of uneven worth. The first movement is labored and has little marked character. It might have been written by any German, technically well-trained, who was acquainted with the music of Tchaikovsky».[67][note 8] Richard Aldrich, who was a music critic for The New York Times, murmured about the overperformance of the work in proportion to its worth, but complimented Rachmaninoff’s playing, stating that, with the assistance of the orchestra, «he made it sound more interesting than it ever has before here».[71] His last concert during the American tour was on 27 January 1910, performing the Isle of the Dead and his concerto under Modest Altschuler with his Russian Symphony Society,[72] who farewelled the homesick Rachmaninoff with appraisal of his Isle of the Dead but dismissal of the concerto as «not in any way comparable to Rachmaninoff’s third concerto».[73][72] Rachmaninoff played the concerto eight times during the tour.[74] Despite the concerto’s popularity, its critical reception has often remained poor.[75]

Following the 1917 October Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family escaped Russia, never to return, seeing the US as a haven for remedying his financial situation; they arrived there one day before Armistice Day, following their temporary stay in Scandinavia.[76] Reginald De Koven praised a Rachmaninoff concerto performance under Walter Damrosch, writing that he rarely saw a New York audience «more moved, excited and wrought up».[74] A 1927 Liverpool Post article called the concerto a «somewhat catchpenny work though it had plently of rather cheap glitter».[37] His last role as a soloist for the concerto was on 18 June 1942 with Vladimir Bakaleinikov leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra,[63] at the Hollywood Bowl.[77] Reviewing the performance in Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, Richard D. Saunders opined that the work is of a «songful quality, imbued with haunting melodies all tinged with sombre pathos and expressed with the graceful refinement characteristic of the composer».[78]

Modern reception and legacy[edit]

No other concerto by Rachmaninoff was as popular with audiences and pianists alike as his Second Concerto;[79] the musicologist Glen Carruthers attributes this popularity with «memorable melodies [which] appear in each movement».[80] Rachmaninoff’s biographer Geoffrey Norris characterized the concerto as «notable for its conciseness and for its lyrical themes, which are just sufficiently contrasted to ensure that they are not spoilt either by overabundance or overexposure.»[81] Stephen Hough on an article with The Guardian posits that the composition is «his most popular, most often performed and, arguably, the most perfect structurally. It sounds as if it wrote itself, so naturally does the music flow».[82] Another article by John Ezard and David Ward calls it one of the «most often performed concertos in the repertoire. Its emergence — in each year so far of the new century — as the British classical listening public’s favourite tune indicates Rachmaninov’s position as perhaps the most popular mainstream composer of the last 70 years.»[83] In 2022, the piece was voted number two in the Classic FM annual «Hall of Fame» poll,[84] and has consistently ranked in the top three.[85]

Numerous films—such as William Dieterle’s September Affair (1950), Charles Vidor’s Rhapsody (1954), and Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955)—borrow themes from the concerto.[86] David Lean’s romantic drama Brief Encounter (1945) utilizes the music widely in its soundtrack,[87] and Frank Borzage’s I’ve Always Loved You (1946) features it heavily;[88] this has further popularized the work.[82] The concerto has also inspired numerous songs,[86][note 9] and is frequently used in figure skating programmes.[89]

Instrumentation[edit]

The concerto is scored for piano and orchestra:[90]

- Woodwinds:

- 2 flutes

- 2 oboes

- 2 clarinets in B♭ (only in the first movement) and A (only in the second and third movements)

- 2 bassoons

- Brass:

- 4 horns in F

- 2 trumpets in B♭

- 3 trombones (2 tenor, 1 bass)

- tuba

- Percussion:

- timpani

- bass drum

- cymbals

- Strings:

- 1st violins

- 2nd violins

- violas

- cellos

- double basses

Structure[edit]

The piece is written in three-movement concerto form:[91]

- Moderato (C minor)

- Adagio sostenuto – Più animato – Tempo I (C minor → E major)

- Allegro scherzando (E major → C minor → C major)

I. Moderato[edit]

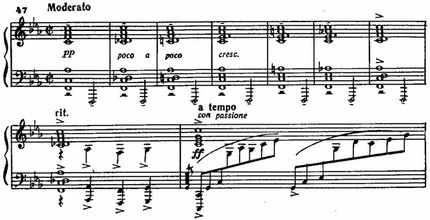

First eight bars of the concerto

The opening movement begins with a series of chromatic bell-like tollings on the piano that build tension, eventually climaxing in the introduction of the main theme by the violins, violas, and first clarinet.

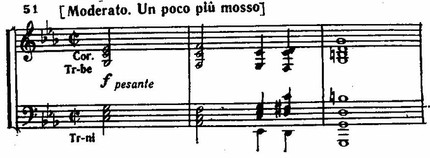

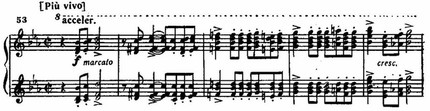

In this first section, while the melody is stated by the orchestra, the piano takes on the role of accompaniment, consisting of rapid oscillating arpeggios between both hands which contribute to the fullness and texture of the section’s sound. The theme soon goes into a slightly lower register, where it is carried on by the cello section, and then is joined by the violins and violas, soaring to a climactic C note. After the statement of the long first theme, a quick and virtuosic «piu mosso» pianistic figuration transition leads into a short series of authentic cadences, accompanied by both a crescendo and an accelerando; this then progresses into the gentle, lyrical second theme in E♭ major, the relative key. The second theme is first stated by the solo piano, with light accompaniment coming from the upper wind instruments. A transition which follows the chromatic scale eventually leads to the final reinstatement of the second theme, this time with the full orchestra at a piano dynamic. The exposition ends with an agitated closing section with scaling arpeggios on the E♭ major scale in both hands.

The agitated and unstable development borrows motifs from both themes, changing keys very often and giving the melody to different instruments while a new musical idea is slowly formed. The sound here, while focused on a particular tonality, has ideas of chromaticism. Two sequences of pianistic figurations lead to a placid, orchestral reinstatement of the first theme in the dominant 7th key of G. The development furthers with motifs from the previous themes, climaxing towards a B♭ major «più vivo» section. A triplet arpeggio section leads into the accelerando section, with the accompanying piano playing chords in both hands, and the string section providing the melody reminiscent of the second theme. The piece reaches a climax with the piano playing dissonant fortississimo (fff) chords, and with the horns and trumpets providing the syncopated melody.

While the orchestra restates the first theme, the piano, that on the other occasion had an accompaniment role, now plays the march-like theme that had been halfly presented in the development, thus making a considerable readjustment in the exposition, as in the main theme, the arpeggios in the piano serve as an accompaniment. This is followed by a piano-solo which continues the first theme and leads into a descending chromatic passage to a pianississimo A♭ major chord. Then the second theme is heard played with a horn solo. The entrance of the piano reverts the key back into C minor, with triplet passages played over a mysterious theme played by the orchestra. Briefly, the piece transitions to a C major glissando in the piano, and is placid until drawn into the agitated closing section in which the movement ends in a C minor fortissimo, with the same authentic cadence as those that followed the first statement of the first theme in the exposition.

II. Adagio sostenuto[edit]

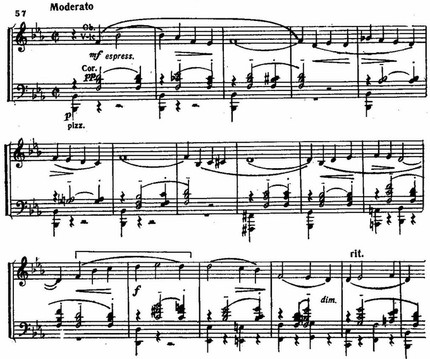

The second movement opens with a series of slow chords in the strings which modulate from the C minor of the previous movement to the E major of this movement.

At the beginning of the A section, the piano enters, playing a simple arpeggiated figure. This opening piano figure was composed in 1891 as the opening of the Romance from Two Pieces For Six Hands. The main theme is initially introduced by the flute, before being developed by an extensive clarinet solo. The motif is passed between the piano and then the strings.

Then the B section is heard. It builds up to a short climax centred on the piano, which leads to cadenza for piano.

The original theme is repeated, and the music appears to die away, finishing with just the soloist in E major.

III. Allegro scherzando[edit]

The last movement opens with a short orchestral introduction that modulates from E major (the key of the previous movement) to C minor, before a piano solo leads to the statement of the agitated first theme.

After the original fast tempo and musical drama ends, a short transition from the piano solo leads to the second lyrical theme in B♭ major is introduced by the oboe and violas. This theme maintains the motif of the first movement’s second theme. The exposition ends with a suspenseful closing section in B♭ major.

After that an extended and energetic development section is heard. The development is based on the first theme of the exposition. It maintains a very improvisational quality, as instruments take turns playing the stormy motifs.

In the recapitulation, the first theme is truncated to only 8 bars on the tutti, because it was widely used in the development section. After the transition, the recapitulation’s 2nd theme appears, this time in D♭ major, half above the tonic. However, after the ominous closing section ends it then builds up into a triumphant climax in C major from the beginning of the coda. The movement ends very triumphantly in the tonic major with the same four-note rhythm ending the Third Concerto in D minor.

Recordings[edit]

Commercial recordings include:

- 1929: Sergei Rachmaninoff with Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski[92]

- 1959: Sviatoslav Richter with Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Stanislaw Wislocki[92]

- 1962: Van Cliburn with Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fritz Reiner[93]

- 1965: Earl Wild with Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Jascha Horenstein[94][95]

- 1970: Alexis Weissenberg with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan[96]

- 1971: Vladimir Ashkenazy with London Symphony Orchestra conducted by André Previn[92]

- 1988: Evgeny Kissin with London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev[97]

- 2005: Leif Ove Andsnes with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Antonio Pappano[98][99]

- 2011: Yuja Wang with Verbier Festival Orchestra conducted by Yuri Temirkanov[100]

- 2013: Anna Federova with Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie conducted by Martin Panteleev[101]

- 2017: Khatia Buniatishvili with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Paavo Järvi[102]

- 2018: Daniil Trifonov with Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin[103]

Transcriptions and derivative works[edit]

Score cover of the concerto arranged for 2 pianos by the composer

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer’s two piano arrangement.[104] Austrian violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler transcribed the second movement for violin and piano in 1940, named Preghiera (Prayer).[105] In 1946, Percy Grainger made a concert transcription of the third movement for piano solo.[106][note 10] The Classical Jazz Quartet’s 2006 arrangement uses thematic sections derived from each movement as grounds for jazz improvisation.[108]

Two songs recorded by Frank Sinatra have roots in the concerto: «I Think of You», from the second theme of the first movement, and «Full Moon and Empty Arms», from the second theme of the third movement.[82] Eric Carmen’s 1975 ballad «All by Myself» is based on the second movement.[89]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Another major factor was a deep-seated antipathy between composers from Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[10][11]

- ^ Cited from Cui, César (1897) in «Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta», p. 3.[12]

- ^ According to So-Ham Kim Chung, the illness was «severe mental depression».[20]

- ^ Max Harrison notes that it is not certain whether there were one or two visits, as Rachmaninoff’s accounts are inconsistent.[29]

- ^ Barrie Martyn formulates that Rachmaninoff might have rudimentarily written or thought out the first movement prior to the rest and that, according to Goldenweiser, the first movement existed in multiple variants, and Rachmaninoff’s indecisiveness to opt for one made him perform the concerto unfinished.[36] Max Harrison states the opposite, namely that the last two movements were composed first.[37]

- ^ Cited from Riesemann, Oskar von (1934). Rachmaninoff’s Recollections, Told to Oskar von Riesemann. New York: Macmillan. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-83695-232-2.[38]

- ^ The concerto was published before his Suite No. 2. Despite that, the suite received the opus number 17, reversing the order.[43]

- ^ Following a performance at the Paris Opera in 1907,[68] a similar objection emerged, where, in spite of winning the praise of the Parisian concertgoers,[69] French critics considered the concerto to be more Germanic rather than Russian.[70]

- ^ For examples, see § Transcriptions and derivative works

- ^ The transcription is catalogued under Concert Transcriptions of Favourite Concertos for piano solo (CT).[107]

References[edit]

- ^ Scott 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 67.

- ^ Scott 2007, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Martyn 2017, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 61.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 97.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Timoshin 2016.

- ^ Cunningham 2001, p. 4.

- ^ a b Martyn 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Chung 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 120.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 87.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 88.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 89.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Norris 2001, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Martyn 2017, p. 125.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2006, p. 93.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 94.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 358.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 132.

- ^ a b Scott 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 31–32, 114.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 361.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 113.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 133.

- ^ Martyn 2017, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 79.

- ^ a b Scott 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 94–95.

- ^ The Guardian 1902.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 94.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 100.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 113.

- ^ a b Davie 2016.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 146.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 162.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Bullock 2022, p. 40.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 83.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 221.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 344.

- ^ Saunders 1942.

- ^ Bullock 2022, p. 225.

- ^ Carruthers 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Hough 2008.

- ^ Ezard & Ward 2004.

- ^ Classic FM 2022.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, p. 62.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bullock 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 356.

- ^ Woodrow Crob, Gary. «A descriptive analysis of the piano concertos of sergei vasilyevich rachmaninoff» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Beek, Michael (28 November 2018). «The best recordings of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2». Immediate Media Company Ltd. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Villella, Frank (27 February 2013). «Remembering Van Cliburn». CSO Archives. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Barnett, Rob. «SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943) Piano Concerto No. 2». Crotchet. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos No 1-4, Rhapsody / Wild, Et Al». ArkivMusic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Tchaikovsky & Rachmaninov: Piano concertos/Weissenberg». Classics Today. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «DISCOGRAPHY | Evgeny Kissin».

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Rachmaninov: Piano concertos 1 & 2/Andsnes». Classics Today. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (27 October 2005). «Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 2, Andsnes/ Berlin Philharmonic/ Pappano». Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «WANG, TEMIRKANOV Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2». Verbier Festival. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto no.2 op.18 — Anna Fedorova — Complete Live Concert — HD». YouTube.

- ^ «Khatia Buniatishvili — Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto Nos 2&3 Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto Nos 2&3 | CD». www.sonyclassical.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (25 October 2018). «Trifonov: Destination Rachmaninov. Departure review – peerless playing». Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 410.

- ^ Biancolli 1998, p. 351.

- ^ Tall 1981, p. 234.

- ^ Tall 1981, p. 229.

- ^ Manheim 2006.

Sources[edit]

Books and journals[edit]

- Bertensson, Sergei; Leyda, Jay (1956). Sergei Rachmaninoff – A Lifetime in Music. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21421-8.

- Biancolli, Amy (1998). Fritz Kreisler: Love’s Sorrow, Love’s Joy. Portland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-037-0.

- Bullock, Philip Ross (2022). Rachmaninoff and His World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-82374-4.

- Carruthers, Glen (2006). «The (Re)Appraisal of Rachmaninov’s Music: Contradictions and Fallacies». The Musical Times. 147 (1896): 44–50.

- Coolidge, Richard (1979). «Architectonic Technique and Innovation in the Rakhmaninov Piano Concertos». The Music Review. 40 (3): 176–216.

- Cunningham, Robert E. (2001). Sergei Rachmaninoff: A Bio-bibliography. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30907-6.

- Gauldin, Robert (2004). «New Twists for Old Endings: Cadenza and Apotheosis in the Romantic Piano Concerto». Intégral. 18/19: 1–23.

- Harrison, Max (2006). Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-826-49312-5.

- Huckvale, David (2022). The Piano on Film. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-4388-5.

- Keefe, Simon P. (2005). The Cambridge companion to the concerto. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83483-4.

- Kerman, Joseph (1999). Concerto conversations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00673-7.

- Martyn, Barrie (2017). Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor. Aldershot: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-859-67809-4.

- Norris, Geoffrey (2001). Rachmaninoff. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-16488-3.

- Norris, Jeremy (1994). The Russian Piano Concerto: The nineteenth century. Vol. 1. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34112-9.

- Piggott, Patrick (1974). Rachmaninov Orchestral Music. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95308-3.

- Rachmaninoff, Sergei (1960). Concerto, Piano, No. 2, C Minor, Op. 18. New York: Broude Brothers, Ltd. – via New York Philharmonic (Leon Levy Digital Archives). (Score contains markings by Leonard Bernstein)

- Ridley, Aaron (1995). Music, value, and the passions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4477-8.

- Roeder, Michael Thomas (1994). A History of the Concerto. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-0-931340-61-1.

- Scott, Michael (2007). Rachmaninoff. Cheltenham: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7242-3.

- Seroff, Victor Ilyitch (1950). Rachmaninoff: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-836-98034-9.

- Steinberg, Michael (1998). The concerto: a listener’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510330-4.

- Tall, David (1981). «Catalogue of Works». In Foreman, Lewis (ed.). The Percy Grainger Companion. London: Thames Publishing. ISBN 978-0-905210-12-4.

- Timoshin, Natalie (2016). «Creativity and Mental Illness: Richard Kogan on Rachmaninoff». Psychiatric Times. 33 (9).

- Tomes, Susan (2021). The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26286-5.

- Walsh, Stephen (1973). «Sergei Rachmaninoff 1873 — 1943». Tempo (105): 12–21.

Other[edit]

- Chung, So-Ham Kim (1988). An analysis of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2 in C Minor opus 18: Aids towards performance (PhD thesis). The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021.

- Davie, Scott (2016). «Concerto Soloist». www.rachmaninoffdiary.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Ezard, John; Ward, David (2004). «‘Rocky 2’ concerto tops poll of classics». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Hough, Stephen (2008). «Five of the best». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Manheim, James (2006). «Review of Kind Of Blue 10004». Kind Of Blue. Retrieved 14 April 2022 – via AllMusic.

- Sanderson, Blair (2013). «Review of RCA Red Seal 88765492602». RCA Red Seal – via AllMusic.

- Sanderson, Blair (2017). «Review of Sony Classical 88985402412». Sony Classical – via AllMusic.

- Saunders, Richard D. (1942). «All-Russian Program Thrills Bowl». Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. Los Angeles. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- «Classic FM Hall of Fame 2022». halloffame.classicfm.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- «Russian Music, New and Old». The Observer. London. 1908. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- «The London Correspondence». The Guardian. London. 1902. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, W. R. (1947), Rachmaninov and his pianoforte concertos: A brief sketch of the composer and his style, London: Hinrichsen Edition Limited, pp. 9–14

External links[edit]

- Piano Concerto No. 2: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free sheet music of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 from Cantorion.org

Rachmaninoff in the early 1900s

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18, is a concerto for piano and orchestra composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff between June 1900 and April 1901. From the summer to the autumn of 1900, he worked on the second and third movements of the concerto, with the first movement causing him difficulties. Both movements of the unfinished concerto were first performed with him as soloist and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] 1900. The first movement was finished in 1901 and the complete work had an astoundingly successful premiere on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1901, again with the composer as soloist and Siloti conducting. Gutheil published the work the same year. The piece established Rachmaninoff’s fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.

After the disastrous 1897 premiere of his First Symphony, Rachmaninoff suffered a psychological breakdown that prevented composition for three years. Although depression sapped his energy, he still engaged in performance. Conducting and piano lessons became necessary to ease his financial position. In 1899, he was supposed to perform the Second Piano Concerto in London, which he had not composed yet due to illness, and instead made a successful conducting debut. The success led to an invitation to return next year with his First Piano Concerto; however, he promised to reappear with a newer and better one. Rachmaninoff was later invited to Leo Tolstoy’s home in hopes of having his writer’s block revoked, but the meeting only worsened his situation. Relatives decided to introduce him to the neurologist Nikolai Dahl, whom he visited daily from January to April 1900, which helped restore his health and confidence in composition. Rachmaninoff dedicated the concerto to Dahl for successfully treating him.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

Sergei Rachmaninoff had been working on his First Symphony from January to September 1895.[1][2] In 1896, after a long hiatus, the music publisher and philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev agreed to include it at one of his Saint Petersburg Russian Symphony Concerts. However, there were setbacks: complaints were raised about the symphony by his teacher Sergei Taneyev upon receiving its score, which elicited revisions by Rachmaninoff, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov expressed dissatisfaction during rehearsal.[3][4] Eventually, the symphony was scheduled to be premiered in March 1897.[5] Before the due date, he was nervous but optimistic due to his prior successes, which included winning the Moscow Conservatory Great Gold Medal and earning the praise of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[6] The premiere, however, was a disaster; Rachmaninoff listened to the cacophonous performance backstage to avoid getting humiliated by the audience and eventually left the hall when the piece finished.[7] The symphony was brutally panned by critics,[8] and apart from issues with the piece, the poor performance of the possibly drunk conductor, Alexander Glazunov, was also to blame.[9][note 1] César Cui wrote:

If there were a conservatoire in Hell, if one of its talented students were instructed to write a programme symphony on «The Seven Plagues of Egypt», and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr Rachmaninoff’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and delighted the inmates of Hell.[note 2]

Rachmaninoff initially remained aloof to the failure of his symphony, but upon reflection, suffered a psychological breakdown that stopped his compositional output for three years.[13] He adopted a lifestyle of heavy drinking to forget about his problems.[14] Depression consumed him,[15] and although he rarely composed, he still engaged in performance, accepting a conducting position by the Russian entrepreneur Savva Mamontov at the Moscow Private Russian Opera from 1897 to 1898.[16] It provided income for the cash-strapped Rachmaninoff; he eventually left as it didn’t allow time for other activities and due to the incompetence of the theater, which turned piano lessons into his main source of income.[17][18]

At the end of 1898, Rachmaninoff was invited to perform in London in April 1899, where he was expected to play his Second Piano Concerto. However, he wrote to the London Philharmonic Society that he couldn’t finish a second concerto due to illness.[19][note 3] The society then requested he play his First Piano Concerto, but he declined, dismissing it as a student piece. Instead, he offered to conduct one of his orchestral pieces, to which the society agreed, provided he also performed at the piano. He made a successful conducting debut, performing The Rock and playing piano pieces such as his hackneyed Prelude in C-sharp minor.[21] The society secretary Francesco Berger invited him to return next year with a performance of the First Concerto. However, he promised to return with a newer and better one,[22][23] although he did not perform it there until 1908.[24] Alexander Goldenweiser, a peer from the same conservatory, wanted to play his new concerto at a Belyayev concert in Saint Petersburg, thinking its consummation was inevitable.[17] Rachmaninoff, who had thoughts of composing it three years earlier, sent a letter to him stating that nothing had been penned so far.[25]

For the rest of the summer and autumn of 1899, Rachmaninoff’s unproductiveness worsened his depression.[26] A friend of the Satins (relatives of Rachmaninoff[27]), in an attempt to revoke the depressed composer’s writer’s block, suggested he visit Leo Tolstoy.[28][note 4] However, his visit to the querulous author only served to increase his despondency, and he became so self-critical that he was rendered unable to compose.[30] The Satins, anxious about his well-being, persuaded him to visit Nikolai Dahl, a neurologist who specialized in hypnosis, with whom they had a good experience. Desperate, he agreed without hesitation.[31] From January to April 1900, he visited him daily free of charge. Dahl restored Rachmaninoff’s health as well as his confidence to compose. Himself a musician, Dahl engaged in lengthy conversations surrounding music with Rachmaninoff, and would repeat a triptych formula while the composer was half-asleep: «You will begin to write your concerto … You will work with great facility … The concerto will be of an excellent quality».[32][33] Even though the results were not readily evident, they were still successful.[34]

Composition and premiere[edit]

In June 1900, after receiving an invitation to perform Mefistofele in La Scala, Feodor Chaliapin invited Rachmaninoff to live with him in Italy, where he sought his advice while studying the opera. During his stay, Rachmaninoff composed the love duet of his opera Francesca da Rimini and also began working on the second and third movements of his Second Piano Concerto.[35] With newfound enthusiasm for composition, he resumed working on them after returning to Russia,[35] which for the rest of the summer and the autumn were being finished «quickly and easily», although the first movement caused him difficulties.[36][note 5] He told his biographer Oscar von Riesemann that «the material grew in bulk, and new musical ideas began to stir within me—far more than I needed for my concerto».[note 6] The two finished movements were to be performed in the Moscow Nobility Hall on 15 December [O.S. 2 December] at a concert arranged for the benefit of the Ladies’ Charity Prison Committee.[39] On the eve of the concert, Rachmaninoff caught a cold, prompting his friends and relatives to stuff him with remedies, filling him with an excess of mulled wine;[40][41] he didn’t want to admit his desire to cancel the performance.[40] With him as soloist with an orchestra after an eight-year hiatus and his cousin Alexander Siloti making his conducting debut, it was an anxious event, but the concert was a great success,[38] easing the worries of his close ones.[40] Ivan Lipaev wrote: «it’s been long since the walls of the Nobility Hall reverberated with such enthusiastic, storming applause as on that evening … This work contains much poetry, beauty, warmth, rich orchestration, healthy and buoyant creative power. Rachmaninoff’s talent is evident throughout.»[42] The German company Gutheil published the concerto as opus number 18 the following year.[38][note 7]

Before continuing composition, Rachmaninoff received financial aid from Siloti to tide him over for the next three years, securing his ability to compose without worrying about rent.[44] By April 1901, while staying with Goldenweiser, he finished the first movement of the concerto and subsequently premiered the full work at a Moscow Philharmonic Society concert on 9 November [O.S. 27 October], again with him at the piano and Siloti conducting.[36][45] Five days before the premiere, however, Rachmaninoff received a letter from Nikita Morozov (his Conservatory colleague[46]) pestering him regarding the structure of the concerto after receiving its score, commenting that the first subject seemed like an introduction to the second one. Frantic, he replied, writing that he concurred with his opinion and was pondering over the first movement. Regardless, it was an astounding success, and Rachmaninoff enjoyed wild acclaim.[47][48] Even Cui, who previously scolded his First Symphony, displayed exuberance over the work in a letter from 1903.[49] The piece established Rachmaninoff’s fame as a concerto composer and is one of his most enduringly popular pieces.[50] He dedicated it to Dahl for his treatment.[51]

Subsequent performances[edit]

The popularity of the Second Piano Concerto grew rapidly, developing global fame after its subsequent performances.[52] Its international progress started with a performance in Germany, where Siloti played it with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Arthur Nikisch’s baton in January 1902.[44] In March, the same duo had a tremendously successful performance in Saint Petersburg;[53] two days preceding this, the Rachmaninoff-Siloti duo performed back in Moscow, with the former conducting and the latter as soloist.[54] May of the same year saw a performance at the Queen’s Hall in London, the soloist being Wassily Sapellnikoff with the Philharmonic Society and Frederic Cowen conducting; London would wait until 1908 for Rachmaninoff to perform it there.[55] «One was quickly persuaded of its genuine excellence and originality», The Guardian wrote of the concerto following the performance.[56] England, however, had already heard the work twice prior to the London premiere, with performances by Siloti in Birmingham and Manchester.[57] Rachmaninoff—enhanced by success from repossessing the ability to compose again, coupled with no more financial worries—repaid the loan from Siloti within one year of receiving the last installment.[54]

After marrying his first cousin Natalia Satina, the newly-wed Rachmaninoff received an invitation to play his concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic under the direction of Vasily Safonov in December. Although the engagement guaranteed him a hefty fee, he was anxious that accepting it would show ingratitude towards Siloti.[58] However, after seeking his help, Taneyev reassured Rachmaninoff that this did not offend Siloti.[59][60] That was followed by concerts in both Vienna and Prague the following spring in 1903 under the same engagement.[61] In late 1904, Rachmaninoff won the Glinka Awards, cash prizes established in Belyayev’s will, receiving 500 rubles for his concerto.[62] Throughout his life, Rachmaninoff soloed the concerto a total of 145 times.[63]

Early reception[edit]

After he fulfilled his 1908 London concert engagement at the Queen’s Hall under Serge Koussevitzky,[64] a flattering review by The Times emerged: «The direct expression of the work, the extraordinary precision and exactitude of Rachmaninoff’s playing, and even the strict economy of movement of arms and hands which he exercises, all contributed to the impression of completeness of performance.»[65]

An advertisement for Rachmaninoff’s debut with an American orchestra at the Philadelphia Academy of Music, where he gave the US premiere of his concerto.

His debut with an American orchestra occurred on 8 November 1909, performing the concerto at the Philadelphia Academy of Music with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Max Fiedler’s baton, including repeat performances in Baltimore and New York City.[66] Critics since the first performance were chiefly dismissive, echoing Philip Hale’s program notes for the debut stating that «The concerto is of uneven worth. The first movement is labored and has little marked character. It might have been written by any German, technically well-trained, who was acquainted with the music of Tchaikovsky».[67][note 8] Richard Aldrich, who was a music critic for The New York Times, murmured about the overperformance of the work in proportion to its worth, but complimented Rachmaninoff’s playing, stating that, with the assistance of the orchestra, «he made it sound more interesting than it ever has before here».[71] His last concert during the American tour was on 27 January 1910, performing the Isle of the Dead and his concerto under Modest Altschuler with his Russian Symphony Society,[72] who farewelled the homesick Rachmaninoff with appraisal of his Isle of the Dead but dismissal of the concerto as «not in any way comparable to Rachmaninoff’s third concerto».[73][72] Rachmaninoff played the concerto eight times during the tour.[74] Despite the concerto’s popularity, its critical reception has often remained poor.[75]

Following the 1917 October Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family escaped Russia, never to return, seeing the US as a haven for remedying his financial situation; they arrived there one day before Armistice Day, following their temporary stay in Scandinavia.[76] Reginald De Koven praised a Rachmaninoff concerto performance under Walter Damrosch, writing that he rarely saw a New York audience «more moved, excited and wrought up».[74] A 1927 Liverpool Post article called the concerto a «somewhat catchpenny work though it had plently of rather cheap glitter».[37] His last role as a soloist for the concerto was on 18 June 1942 with Vladimir Bakaleinikov leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra,[63] at the Hollywood Bowl.[77] Reviewing the performance in Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, Richard D. Saunders opined that the work is of a «songful quality, imbued with haunting melodies all tinged with sombre pathos and expressed with the graceful refinement characteristic of the composer».[78]

Modern reception and legacy[edit]

No other concerto by Rachmaninoff was as popular with audiences and pianists alike as his Second Concerto;[79] the musicologist Glen Carruthers attributes this popularity with «memorable melodies [which] appear in each movement».[80] Rachmaninoff’s biographer Geoffrey Norris characterized the concerto as «notable for its conciseness and for its lyrical themes, which are just sufficiently contrasted to ensure that they are not spoilt either by overabundance or overexposure.»[81] Stephen Hough on an article with The Guardian posits that the composition is «his most popular, most often performed and, arguably, the most perfect structurally. It sounds as if it wrote itself, so naturally does the music flow».[82] Another article by John Ezard and David Ward calls it one of the «most often performed concertos in the repertoire. Its emergence — in each year so far of the new century — as the British classical listening public’s favourite tune indicates Rachmaninov’s position as perhaps the most popular mainstream composer of the last 70 years.»[83] In 2022, the piece was voted number two in the Classic FM annual «Hall of Fame» poll,[84] and has consistently ranked in the top three.[85]

Numerous films—such as William Dieterle’s September Affair (1950), Charles Vidor’s Rhapsody (1954), and Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955)—borrow themes from the concerto.[86] David Lean’s romantic drama Brief Encounter (1945) utilizes the music widely in its soundtrack,[87] and Frank Borzage’s I’ve Always Loved You (1946) features it heavily;[88] this has further popularized the work.[82] The concerto has also inspired numerous songs,[86][note 9] and is frequently used in figure skating programmes.[89]

Instrumentation[edit]

The concerto is scored for piano and orchestra:[90]

- Woodwinds:

- 2 flutes

- 2 oboes

- 2 clarinets in B♭ (only in the first movement) and A (only in the second and third movements)

- 2 bassoons

- Brass:

- 4 horns in F

- 2 trumpets in B♭

- 3 trombones (2 tenor, 1 bass)

- tuba

- Percussion:

- timpani

- bass drum

- cymbals

- Strings:

- 1st violins

- 2nd violins

- violas

- cellos

- double basses

Structure[edit]

The piece is written in three-movement concerto form:[91]

- Moderato (C minor)

- Adagio sostenuto – Più animato – Tempo I (C minor → E major)

- Allegro scherzando (E major → C minor → C major)

I. Moderato[edit]

First eight bars of the concerto

The opening movement begins with a series of chromatic bell-like tollings on the piano that build tension, eventually climaxing in the introduction of the main theme by the violins, violas, and first clarinet.

In this first section, while the melody is stated by the orchestra, the piano takes on the role of accompaniment, consisting of rapid oscillating arpeggios between both hands which contribute to the fullness and texture of the section’s sound. The theme soon goes into a slightly lower register, where it is carried on by the cello section, and then is joined by the violins and violas, soaring to a climactic C note. After the statement of the long first theme, a quick and virtuosic «piu mosso» pianistic figuration transition leads into a short series of authentic cadences, accompanied by both a crescendo and an accelerando; this then progresses into the gentle, lyrical second theme in E♭ major, the relative key. The second theme is first stated by the solo piano, with light accompaniment coming from the upper wind instruments. A transition which follows the chromatic scale eventually leads to the final reinstatement of the second theme, this time with the full orchestra at a piano dynamic. The exposition ends with an agitated closing section with scaling arpeggios on the E♭ major scale in both hands.

The agitated and unstable development borrows motifs from both themes, changing keys very often and giving the melody to different instruments while a new musical idea is slowly formed. The sound here, while focused on a particular tonality, has ideas of chromaticism. Two sequences of pianistic figurations lead to a placid, orchestral reinstatement of the first theme in the dominant 7th key of G. The development furthers with motifs from the previous themes, climaxing towards a B♭ major «più vivo» section. A triplet arpeggio section leads into the accelerando section, with the accompanying piano playing chords in both hands, and the string section providing the melody reminiscent of the second theme. The piece reaches a climax with the piano playing dissonant fortississimo (fff) chords, and with the horns and trumpets providing the syncopated melody.

While the orchestra restates the first theme, the piano, that on the other occasion had an accompaniment role, now plays the march-like theme that had been halfly presented in the development, thus making a considerable readjustment in the exposition, as in the main theme, the arpeggios in the piano serve as an accompaniment. This is followed by a piano-solo which continues the first theme and leads into a descending chromatic passage to a pianississimo A♭ major chord. Then the second theme is heard played with a horn solo. The entrance of the piano reverts the key back into C minor, with triplet passages played over a mysterious theme played by the orchestra. Briefly, the piece transitions to a C major glissando in the piano, and is placid until drawn into the agitated closing section in which the movement ends in a C minor fortissimo, with the same authentic cadence as those that followed the first statement of the first theme in the exposition.

II. Adagio sostenuto[edit]

The second movement opens with a series of slow chords in the strings which modulate from the C minor of the previous movement to the E major of this movement.

At the beginning of the A section, the piano enters, playing a simple arpeggiated figure. This opening piano figure was composed in 1891 as the opening of the Romance from Two Pieces For Six Hands. The main theme is initially introduced by the flute, before being developed by an extensive clarinet solo. The motif is passed between the piano and then the strings.

Then the B section is heard. It builds up to a short climax centred on the piano, which leads to cadenza for piano.

The original theme is repeated, and the music appears to die away, finishing with just the soloist in E major.

III. Allegro scherzando[edit]

The last movement opens with a short orchestral introduction that modulates from E major (the key of the previous movement) to C minor, before a piano solo leads to the statement of the agitated first theme.

After the original fast tempo and musical drama ends, a short transition from the piano solo leads to the second lyrical theme in B♭ major is introduced by the oboe and violas. This theme maintains the motif of the first movement’s second theme. The exposition ends with a suspenseful closing section in B♭ major.

After that an extended and energetic development section is heard. The development is based on the first theme of the exposition. It maintains a very improvisational quality, as instruments take turns playing the stormy motifs.

In the recapitulation, the first theme is truncated to only 8 bars on the tutti, because it was widely used in the development section. After the transition, the recapitulation’s 2nd theme appears, this time in D♭ major, half above the tonic. However, after the ominous closing section ends it then builds up into a triumphant climax in C major from the beginning of the coda. The movement ends very triumphantly in the tonic major with the same four-note rhythm ending the Third Concerto in D minor.

Recordings[edit]

Commercial recordings include:

- 1929: Sergei Rachmaninoff with Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski[92]

- 1959: Sviatoslav Richter with Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Stanislaw Wislocki[92]

- 1962: Van Cliburn with Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fritz Reiner[93]

- 1965: Earl Wild with Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Jascha Horenstein[94][95]

- 1970: Alexis Weissenberg with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan[96]

- 1971: Vladimir Ashkenazy with London Symphony Orchestra conducted by André Previn[92]

- 1988: Evgeny Kissin with London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev[97]

- 2005: Leif Ove Andsnes with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Antonio Pappano[98][99]

- 2011: Yuja Wang with Verbier Festival Orchestra conducted by Yuri Temirkanov[100]

- 2013: Anna Federova with Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie conducted by Martin Panteleev[101]

- 2017: Khatia Buniatishvili with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Paavo Järvi[102]

- 2018: Daniil Trifonov with Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin[103]

Transcriptions and derivative works[edit]

Score cover of the concerto arranged for 2 pianos by the composer

In 1901, Gutheil published the concerto along with the composer’s two piano arrangement.[104] Austrian violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler transcribed the second movement for violin and piano in 1940, named Preghiera (Prayer).[105] In 1946, Percy Grainger made a concert transcription of the third movement for piano solo.[106][note 10] The Classical Jazz Quartet’s 2006 arrangement uses thematic sections derived from each movement as grounds for jazz improvisation.[108]

Two songs recorded by Frank Sinatra have roots in the concerto: «I Think of You», from the second theme of the first movement, and «Full Moon and Empty Arms», from the second theme of the third movement.[82] Eric Carmen’s 1975 ballad «All by Myself» is based on the second movement.[89]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Another major factor was a deep-seated antipathy between composers from Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[10][11]

- ^ Cited from Cui, César (1897) in «Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta», p. 3.[12]

- ^ According to So-Ham Kim Chung, the illness was «severe mental depression».[20]

- ^ Max Harrison notes that it is not certain whether there were one or two visits, as Rachmaninoff’s accounts are inconsistent.[29]

- ^ Barrie Martyn formulates that Rachmaninoff might have rudimentarily written or thought out the first movement prior to the rest and that, according to Goldenweiser, the first movement existed in multiple variants, and Rachmaninoff’s indecisiveness to opt for one made him perform the concerto unfinished.[36] Max Harrison states the opposite, namely that the last two movements were composed first.[37]

- ^ Cited from Riesemann, Oskar von (1934). Rachmaninoff’s Recollections, Told to Oskar von Riesemann. New York: Macmillan. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-83695-232-2.[38]

- ^ The concerto was published before his Suite No. 2. Despite that, the suite received the opus number 17, reversing the order.[43]

- ^ Following a performance at the Paris Opera in 1907,[68] a similar objection emerged, where, in spite of winning the praise of the Parisian concertgoers,[69] French critics considered the concerto to be more Germanic rather than Russian.[70]

- ^ For examples, see § Transcriptions and derivative works

- ^ The transcription is catalogued under Concert Transcriptions of Favourite Concertos for piano solo (CT).[107]

References[edit]

- ^ Scott 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 67.

- ^ Scott 2007, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Martyn 2017, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 61.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 97.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Timoshin 2016.

- ^ Cunningham 2001, p. 4.

- ^ a b Martyn 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Chung 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 120.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 87.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 88.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 89.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Norris 2001, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Martyn 2017, p. 125.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2006, p. 93.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 94.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 358.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Martyn 2017, p. 132.

- ^ a b Scott 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 31–32, 114.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 361.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 113.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 133.

- ^ Martyn 2017, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Seroff 1950, p. 79.

- ^ a b Scott 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Harrison 2006, pp. 94–95.

- ^ The Guardian 1902.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 94.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 100.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 113.

- ^ a b Davie 2016.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 146.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 162.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Seroff 1950, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Bullock 2022, p. 40.

- ^ Scott 2007, p. 83.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 221.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Norris 2001, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 344.

- ^ Saunders 1942.

- ^ Bullock 2022, p. 225.

- ^ Carruthers 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Norris 2001, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Hough 2008.

- ^ Ezard & Ward 2004.

- ^ Classic FM 2022.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, p. 62.

- ^ a b Harrison 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Huckvale 2022, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bullock 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Steinberg 1998, p. 356.

- ^ Woodrow Crob, Gary. «A descriptive analysis of the piano concertos of sergei vasilyevich rachmaninoff» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Beek, Michael (28 November 2018). «The best recordings of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2». Immediate Media Company Ltd. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Villella, Frank (27 February 2013). «Remembering Van Cliburn». CSO Archives. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Barnett, Rob. «SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943) Piano Concerto No. 2». Crotchet. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos No 1-4, Rhapsody / Wild, Et Al». ArkivMusic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Tchaikovsky & Rachmaninov: Piano concertos/Weissenberg». Classics Today. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «DISCOGRAPHY | Evgeny Kissin».

- ^ Distler, Jed. «Rachmaninov: Piano concertos 1 & 2/Andsnes». Classics Today. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (27 October 2005). «Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 2, Andsnes/ Berlin Philharmonic/ Pappano». Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «WANG, TEMIRKANOV Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2». Verbier Festival. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ «Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto no.2 op.18 — Anna Fedorova — Complete Live Concert — HD». YouTube.

- ^ «Khatia Buniatishvili — Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto Nos 2&3 Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto Nos 2&3 | CD». www.sonyclassical.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (25 October 2018). «Trifonov: Destination Rachmaninov. Departure review – peerless playing». Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Bertensson & Leyda 1956, p. 410.

- ^ Biancolli 1998, p. 351.

- ^ Tall 1981, p. 234.

- ^ Tall 1981, p. 229.

- ^ Manheim 2006.

Sources[edit]

Books and journals[edit]

- Bertensson, Sergei; Leyda, Jay (1956). Sergei Rachmaninoff – A Lifetime in Music. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21421-8.

- Biancolli, Amy (1998). Fritz Kreisler: Love’s Sorrow, Love’s Joy. Portland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-037-0.

- Bullock, Philip Ross (2022). Rachmaninoff and His World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-82374-4.

- Carruthers, Glen (2006). «The (Re)Appraisal of Rachmaninov’s Music: Contradictions and Fallacies». The Musical Times. 147 (1896): 44–50.

- Coolidge, Richard (1979). «Architectonic Technique and Innovation in the Rakhmaninov Piano Concertos». The Music Review. 40 (3): 176–216.

- Cunningham, Robert E. (2001). Sergei Rachmaninoff: A Bio-bibliography. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30907-6.

- Gauldin, Robert (2004). «New Twists for Old Endings: Cadenza and Apotheosis in the Romantic Piano Concerto». Intégral. 18/19: 1–23.

- Harrison, Max (2006). Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-826-49312-5.

- Huckvale, David (2022). The Piano on Film. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-4388-5.

- Keefe, Simon P. (2005). The Cambridge companion to the concerto. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83483-4.

- Kerman, Joseph (1999). Concerto conversations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00673-7.

- Martyn, Barrie (2017). Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor. Aldershot: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-859-67809-4.

- Norris, Geoffrey (2001). Rachmaninoff. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-16488-3.

- Norris, Jeremy (1994). The Russian Piano Concerto: The nineteenth century. Vol. 1. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34112-9.

- Piggott, Patrick (1974). Rachmaninov Orchestral Music. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95308-3.

- Rachmaninoff, Sergei (1960). Concerto, Piano, No. 2, C Minor, Op. 18. New York: Broude Brothers, Ltd. – via New York Philharmonic (Leon Levy Digital Archives). (Score contains markings by Leonard Bernstein)

- Ridley, Aaron (1995). Music, value, and the passions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4477-8.

- Roeder, Michael Thomas (1994). A History of the Concerto. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-0-931340-61-1.

- Scott, Michael (2007). Rachmaninoff. Cheltenham: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7242-3.

- Seroff, Victor Ilyitch (1950). Rachmaninoff: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-836-98034-9.

- Steinberg, Michael (1998). The concerto: a listener’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510330-4.

- Tall, David (1981). «Catalogue of Works». In Foreman, Lewis (ed.). The Percy Grainger Companion. London: Thames Publishing. ISBN 978-0-905210-12-4.

- Timoshin, Natalie (2016). «Creativity and Mental Illness: Richard Kogan on Rachmaninoff». Psychiatric Times. 33 (9).

- Tomes, Susan (2021). The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26286-5.

- Walsh, Stephen (1973). «Sergei Rachmaninoff 1873 — 1943». Tempo (105): 12–21.

Other[edit]

- Chung, So-Ham Kim (1988). An analysis of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 2 in C Minor opus 18: Aids towards performance (PhD thesis). The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021.

- Davie, Scott (2016). «Concerto Soloist». www.rachmaninoffdiary.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Ezard, John; Ward, David (2004). «‘Rocky 2’ concerto tops poll of classics». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Hough, Stephen (2008). «Five of the best». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Manheim, James (2006). «Review of Kind Of Blue 10004». Kind Of Blue. Retrieved 14 April 2022 – via AllMusic.

- Sanderson, Blair (2013). «Review of RCA Red Seal 88765492602». RCA Red Seal – via AllMusic.

- Sanderson, Blair (2017). «Review of Sony Classical 88985402412». Sony Classical – via AllMusic.

- Saunders, Richard D. (1942). «All-Russian Program Thrills Bowl». Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. Los Angeles. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- «Classic FM Hall of Fame 2022». halloffame.classicfm.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- «Russian Music, New and Old». The Observer. London. 1908. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- «The London Correspondence». The Guardian. London. 1902. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, W. R. (1947), Rachmaninov and his pianoforte concertos: A brief sketch of the composer and his style, London: Hinrichsen Edition Limited, pp. 9–14

External links[edit]

- Piano Concerto No. 2: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free sheet music of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 from Cantorion.org

С. Рахманинов Концерт для фортепиано с оркестром №2

Второй концерт Сергея Рахманинова стал знаковым для композитора, прочно войдя в историю мировой музыки и заняв там особое место. До сих пор он остается едва ли не самым популярным произведением Рахманинова, благодаря своей необыкновенной красоте, эмоциональности, художественному замыслу и воплощению. Исследователи по праву называют этот концерт гениальной поэмой о Родине.

Историю создания Концерта для фортепиано с оркестром Рахманинова, а также интересные факты и музыкальное содержание произведения читайте на нашей странице.

История создания

Второй концерт для фортепиано с оркестром до минор был написан в 1900 году. Стоит отметить, что его появлению предшествовал крайне тяжелый период в жизни композитора – неудачная премьера Первой симфонии в 1897 году. Это сильно отразилось на душевном состоянии Рахманинова, из-за чего он даже отказался полностью от композиции на несколько лет, пребывая в сильнейшем творческом кризисе.

Такое состояние продолжалось у музыканта три года. Он постоянно жаловался на усталость, бессонницу, острую боль в спине, руках. Друзья и близкие пытались всячески помочь ему, даже организовали встречу со Львом Толстым. Но это не помогло, а наоборот, еще более усугубило ситуацию. После возвращения домой, Рахманинова стали мучить галлюцинации. Близким пришлось обратиться за помощью к специалисту. Благодаря помощи известного врача невропатолога и гипнотизера Н.В. Даля, Рахманинову удалось восстановиться.

За счет материальной поддержки Александра Зилоти, Рахманинов смог оставить педагогическую деятельность в Мариинском училище, которая его несколько тяготила и посвятить себя вновь композиции.

Тяжелая депрессия позади, а это значит, что за все три года у талантливого композитора накопились творческие силы и идеи. Именно в этот период времени появляются сочинения Рахманинова, которые символизируют собой более высокую ступень его художественного мастерства.

Во Втором концерте композитор предстает перед публикой уже как зрелый художник, со своим особым мастерством, стилем, полностью и весьма ярко владеющий всеми доступными выразительными средствами, как настоящий мастер крупной формы. Творческий путь, намеченный еще в Первой симфонии, теперь окончательно определяется – это преобладание лирико-эпического симфонизма, который неизменно опирается на национальную мелодику и метроритм. Все яркие события детства, посещение служб в московском Андрониковом монастыре, изучение хоровых произведений А. Кастальского – все это оказало огромное влияние на формирование его индивидуального стиля.

24 апреля Сергей Васильевич решил представить небольшой публике первую часть концерта. Это произошло на собрании музыкантов у Гольденвейзера в 1901 году. Вот только слушатели не сразу оценили эту прекрасную и самобытную музыку.

Однако первое публичное исполнение всего концерта принесло произведению всеобщее признание и любовь слушателей. Впервые Второй концерт для фортепиано с оркестром до минор был представлен публике 27 октября 1901 года в исполнении самого композитора. Оркестром дирижировал А.И. Зилоти. Главная тема первой части произвела неизгладимое впечатление на слушателей и поразила буквально всех, кто присутствовал в зале.

Публика Санкт-Петербурга смогла познакомиться с концертом Рахманинова 29 марта 1902 года в исполнении А. Зилоти. Концертом дирижировал А. Никиш.

Интересные факты

- Свой концерт Рахманинов посвятил врачу-гипнотизеру Николаю Далю, у которого проходил лечение, преодолевая душевный кризис.

- В 1904 году Сергей Васильевич получил Глинкинскую премию за свой Второй концерт, утвержденную известным меценатом М. Беляевым.

- Обретя популярность, рахманиновский концерт вошел в репертуар большинства именитых пианистов, среди которых Святослав Рихтер, Денис Мацуев, Ван Клиберн, Артур Рубинштейн и многие другие.

- У Второго концерта очень обширная фильмография. Музыку этого прекрасного произведения можно услышать во многих фильмах: «Рай» (2016), «Женщина и Мужчина» (2010), «Частная жизнь» (1982), «Поэма о крыльях» (1979), «Весна на Заречной улице» (1956), «Ветка сирени» (2007), «Бинго-Бонго» (1982), «Короткая встреча» (1974), «Бункер», мультфильм «Свинья-копилка» (1963) и др.

- Как вспоминают современники, известный композитор С. Танеев, когда впервые прослушал вторую часть рахманиновского концерта, признался, что это гениально и даже прослезился от эмоций.

- По своему характеру, произведение Рахманинова близко к симфонизированной лирической поэме.

- Причиной творческого кризиса (затишья) у Рахманинова считается не только провал его Первой симфонии, но и переживания личного характера. Дело в том, что он узнал о замужестве возлюбленной, которая предпочла другого молодого человека.

- Во время первого исполнения Второго концерта в зале присутствовал Н. Даль. Рахманинов обратился к нему с речью и признался, что это именно его концерт. После этого, еще на многих выступлениях Сергея Васильевича присутствовал личный врач композитора Н.В. Даль, который всегда сидел на первых рядах. Таким образом, он помогал музыканту справляться с сильным волнением перед аудиторией.

Содержание

Первая часть основана на величавой теме, которая символизирует собой образ Родины. Она невероятно прекрасная и вместе с тем могучая. Концерт открывается очень ярко – тяжелыми аккордами, которые можно сравнить разве что с ударами набата. Они нагнетают напряжение до предела. Сама мелодия развивается неторопливо, медленной поступью, но необычайно напевно. В то же время чувствуется некая напряженность в музыке, которую рассеивает наступление побочной партии. Как обычно, она контрастна главной. Это уже образ любви, счастья с оттенком томления.

Вторая часть Adagio sostenuto – это лирический центр концерта. Вся часть написана в едином эмоциональном фоне и вырастает из одного тематического зерна. Сама музыка невероятно мечтательная, спокойная, символизирует собой красоту природы и гармонию. Именно в этой части впервые появляется типичный рахманиновский тип мелодии – очень легкой, трепетной, которая как бы «парит». Этот мягкий образ еще больше оттеняется сопровождением – мягким и колышущемся, которое расцвечивает основную мелодию необыкновенными красками.