| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative name | aluminum (U.S., Canada) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Al) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 13 (boron group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 933.47 K (660.32 °C, 1220.58 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2743 K (2470 °C, 4478 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 2.70 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 2.375 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 10.71 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 284 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.20 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0,[3] +1,[4] +2,[5] +3 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.61 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 143 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 121±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 184 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of aluminium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (rolled) 5000 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 23.1 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 237 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 26.5 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +16.5×10−6 cm3/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 70 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 26 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 76 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.75 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 160–350 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 160–550 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7429-90-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | from alumine, obsolete name for alumina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Antoine Lavoisier (1782) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Hans Christian Ørsted (1824) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Humphry Davy (1812[a]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of aluminium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Aluminium (aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It has a great affinity towards oxygen, and forms a protective layer of oxide on the surface when exposed to air. Aluminium visually resembles silver, both in its color and in its great ability to reflect light. It is soft, non-magnetic and ductile. It has one stable isotope, 27Al; this isotope is very common, making aluminium the twelfth most common element in the Universe. The radioactivity of 26Al is used in radiodating.

Chemically, aluminium is a post-transition metal in the boron group; as is common for the group, aluminium forms compounds primarily in the +3 oxidation state. The aluminium cation Al3+ is small and highly charged; as such, it is polarizing, and bonds aluminium forms tend towards covalency. The strong affinity towards oxygen leads to aluminium’s common association with oxygen in nature in the form of oxides; for this reason, aluminium is found on Earth primarily in rocks in the crust, where it is the third most abundant element after oxygen and silicon, rather than in the mantle, and virtually never as the free metal.

The discovery of aluminium was announced in 1825 by Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted. The first industrial production of aluminium was initiated by French chemist Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville in 1856. Aluminium became much more available to the public with the Hall–Héroult process developed independently by French engineer Paul Héroult and American engineer Charles Martin Hall in 1886, and the mass production of aluminium led to its extensive use in industry and everyday life. In World Wars I and II, aluminium was a crucial strategic resource for aviation. In 1954, aluminium became the most produced non-ferrous metal, surpassing copper. In the 21st century, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan.

Despite its prevalence in the environment, no living organism is known to use aluminium salts metabolically, but aluminium is well tolerated by plants and animals. Because of the abundance of these salts, the potential for a biological role for them is of interest, and studies continue.

Physical characteristics

Isotopes

Of aluminium isotopes, only 27

Al

is stable. This situation is common for elements with an odd atomic number.[b] It is the only primordial aluminium isotope, i.e. the only one that has existed on Earth in its current form since the formation of the planet. Nearly all aluminium on Earth is present as this isotope, which makes it a mononuclidic element and means that its standard atomic weight is virtually the same as that of the isotope. This makes aluminium very useful in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), as its single stable isotope has a high NMR sensitivity.[8] The standard atomic weight of aluminium is low in comparison with many other metals.[c]

All other isotopes of aluminium are radioactive. The most stable of these is 26Al: while it was present along with stable 27Al in the interstellar medium from which the Solar System formed, having been produced by stellar nucleosynthesis as well, its half-life is only 717,000 years and therefore a detectable amount has not survived since the formation of the planet.[10] However, minute traces of 26Al are produced from argon in the atmosphere by spallation caused by cosmic ray protons. The ratio of 26Al to 10Be has been used for radiodating of geological processes over 105 to 106 year time scales, in particular transport, deposition, sediment storage, burial times, and erosion.[11] Most meteorite scientists believe that the energy released by the decay of 26Al was responsible for the melting and differentiation of some asteroids after their formation 4.55 billion years ago.[12]

The remaining isotopes of aluminium, with mass numbers ranging from 22 to 43, all have half-lives well under an hour. Three metastable states are known, all with half-lives under a minute.[7]

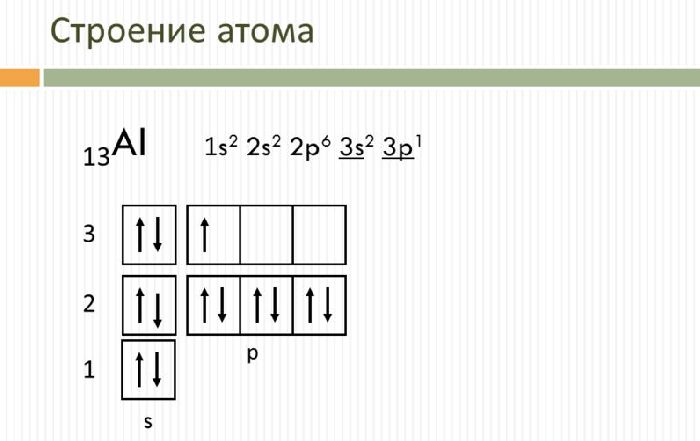

Electron shell

An aluminium atom has 13 electrons, arranged in an electron configuration of [Ne] 3s2 3p1,[13] with three electrons beyond a stable noble gas configuration. Accordingly, the combined first three ionization energies of aluminium are far lower than the fourth ionization energy alone.[14] Such an electron configuration is shared with the other well-characterized members of its group, boron, gallium, indium, and thallium; it is also expected for nihonium. Aluminium can surrender its three outermost electrons in many chemical reactions (see below). The electronegativity of aluminium is 1.61 (Pauling scale).[15]

High-resolution STEM-HAADF micrograph of Al atoms viewed along the [001] zone axis.

A free aluminium atom has a radius of 143 pm.[16] With the three outermost electrons removed, the radius shrinks to 39 pm for a 4-coordinated atom or 53.5 pm for a 6-coordinated atom.[16] At standard temperature and pressure, aluminium atoms (when not affected by atoms of other elements) form a face-centered cubic crystal system bound by metallic bonding provided by atoms’ outermost electrons; hence aluminium (at these conditions) is a metal.[17] This crystal system is shared by many other metals, such as lead and copper; the size of a unit cell of aluminium is comparable to that of those other metals.[17] The system, however, is not shared by the other members of its group; boron has ionization energies too high to allow metallization, thallium has a hexagonal close-packed structure, and gallium and indium have unusual structures that are not close-packed like those of aluminium and thallium. The few electrons that are available for metallic bonding in aluminium metal are a probable cause for it being soft with a low melting point and low electrical resistivity.[18]

Bulk

Aluminium metal has an appearance ranging from silvery white to dull gray, depending on the surface roughness.[d] Aluminium mirrors are the most reflective of all metal mirrors for the near ultraviolet and far infrared light, and one of the most reflective in the visible spectrum, nearly on par with silver, and the two therefore look similar. Aluminium is also good at reflecting solar radiation, although prolonged exposure to sunlight in air adds wear to the surface of the metal; this may be prevented if aluminium is anodized, which adds a protective layer of oxide on the surface.

The density of aluminium is 2.70 g/cm3, about 1/3 that of steel, much lower than other commonly encountered metals, making aluminium parts easily identifiable through their lightness.[21] Aluminium’s low density compared to most other metals arises from the fact that its nuclei are much lighter, while difference in the unit cell size does not compensate for this difference. The only lighter metals are the metals of groups 1 and 2, which apart from beryllium and magnesium are too reactive for structural use (and beryllium is very toxic).[22] Aluminium is not as strong or stiff as steel, but the low density makes up for this in the aerospace industry and for many other applications where light weight and relatively high strength are crucial.[23]

Pure aluminium is quite soft and lacking in strength. In most applications various aluminium alloys are used instead because of their higher strength and hardness.[24] The yield strength of pure aluminium is 7–11 MPa, while aluminium alloys have yield strengths ranging from 200 MPa to 600 MPa.[25] Aluminium is ductile, with a percent elongation of 50-70%,[26] and malleable allowing it to be easily drawn and extruded.[27] It is also easily machined and cast.[27]

Aluminium is an excellent thermal and electrical conductor, having around 60% the conductivity of copper, both thermal and electrical, while having only 30% of copper’s density.[28] Aluminium is capable of superconductivity, with a superconducting critical temperature of 1.2 kelvin and a critical magnetic field of about 100 gauss (10 milliteslas).[29] It is paramagnetic and thus essentially unaffected by static magnetic fields.[30] The high electrical conductivity, however, means that it is strongly affected by alternating magnetic fields through the induction of eddy currents.[31]

Chemistry

Aluminium combines characteristics of pre- and post-transition metals. Since it has few available electrons for metallic bonding, like its heavier group 13 congeners, it has the characteristic physical properties of a post-transition metal, with longer-than-expected interatomic distances.[18] Furthermore, as Al3+ is a small and highly charged cation, it is strongly polarizing and bonding in aluminium compounds tends towards covalency;[32] this behavior is similar to that of beryllium (Be2+), and the two display an example of a diagonal relationship.[33]

The underlying core under aluminium’s valence shell is that of the preceding noble gas, whereas those of its heavier congeners gallium, indium, thallium, and nihonium also include a filled d-subshell and in some cases a filled f-subshell. Hence, the inner electrons of aluminium shield the valence electrons almost completely, unlike those of aluminium’s heavier congeners. As such, aluminium is the most electropositive metal in its group, and its hydroxide is in fact more basic than that of gallium.[32][e] Aluminium also bears minor similarities to the metalloid boron in the same group: AlX3 compounds are valence isoelectronic to BX3 compounds (they have the same valence electronic structure), and both behave as Lewis acids and readily form adducts.[34] Additionally, one of the main motifs of boron chemistry is regular icosahedral structures, and aluminium forms an important part of many icosahedral quasicrystal alloys, including the Al–Zn–Mg class.[35]

Aluminium has a high chemical affinity to oxygen, which renders it suitable for use as a reducing agent in the thermite reaction. A fine powder of aluminium metal reacts explosively on contact with liquid oxygen; under normal conditions, however, aluminium forms a thin oxide layer (~5 nm at room temperature)[36] that protects the metal from further corrosion by oxygen, water, or dilute acid, a process termed passivation.[32][37] Because of its general resistance to corrosion, aluminium is one of the few metals that retains silvery reflectance in finely powdered form, making it an important component of silver-colored paints.[38] Aluminium is not attacked by oxidizing acids because of its passivation. This allows aluminium to be used to store reagents such as nitric acid, concentrated sulfuric acid, and some organic acids.[39]

In hot concentrated hydrochloric acid, aluminium reacts with water with evolution of hydrogen, and in aqueous sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide at room temperature to form aluminates—protective passivation under these conditions is negligible.[40] Aqua regia also dissolves aluminium.[39] Aluminium is corroded by dissolved chlorides, such as common sodium chloride, which is why household plumbing is never made from aluminium.[40] The oxide layer on aluminium is also destroyed by contact with mercury due to amalgamation or with salts of some electropositive metals.[32] As such, the strongest aluminium alloys are less corrosion-resistant due to galvanic reactions with alloyed copper,[25] and aluminium’s corrosion resistance is greatly reduced by aqueous salts, particularly in the presence of dissimilar metals.[18]

Aluminium reacts with most nonmetals upon heating, forming compounds such as aluminium nitride (AlN), aluminium sulfide (Al2S3), and the aluminium halides (AlX3). It also forms a wide range of intermetallic compounds involving metals from every group on the periodic table.[32]

Inorganic compounds

The vast majority of compounds, including all aluminium-containing minerals and all commercially significant aluminium compounds, feature aluminium in the oxidation state 3+. The coordination number of such compounds varies, but generally Al3+ is either six- or four-coordinate. Almost all compounds of aluminium(III) are colorless.[32]

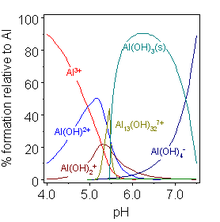

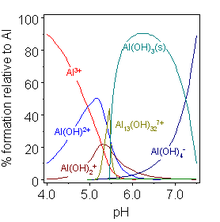

Aluminium hydrolysis as a function of pH. Coordinated water molecules are omitted. (Data from Baes and Mesmer)[41]

In aqueous solution, Al3+ exists as the hexaaqua cation [Al(H2O)6]3+, which has an approximate Ka of 10−5.[8] Such solutions are acidic as this cation can act as a proton donor and progressively hydrolyze until a precipitate of aluminium hydroxide, Al(OH)3, forms. This is useful for clarification of water, as the precipitate nucleates on suspended particles in the water, hence removing them. Increasing the pH even further leads to the hydroxide dissolving again as aluminate, [Al(H2O)2(OH)4]−, is formed.

Aluminium hydroxide forms both salts and aluminates and dissolves in acid and alkali, as well as on fusion with acidic and basic oxides.[32] This behavior of Al(OH)3 is termed amphoterism and is characteristic of weakly basic cations that form insoluble hydroxides and whose hydrated species can also donate their protons. One effect of this is that aluminium salts with weak acids are hydrolyzed in water to the aquated hydroxide and the corresponding nonmetal hydride: for example, aluminium sulfide yields hydrogen sulfide. However, some salts like aluminium carbonate exist in aqueous solution but are unstable as such; and only incomplete hydrolysis takes place for salts with strong acids, such as the halides, nitrate, and sulfate. For similar reasons, anhydrous aluminium salts cannot be made by heating their «hydrates»: hydrated aluminium chloride is in fact not AlCl3·6H2O but [Al(H2O)6]Cl3, and the Al–O bonds are so strong that heating is not sufficient to break them and form Al–Cl bonds instead:[32]

- 2[Al(H2O)6]Cl3 heat→ Al2O3 + 6 HCl + 9 H2O

All four trihalides are well known. Unlike the structures of the three heavier trihalides, aluminium fluoride (AlF3) features six-coordinate aluminium, which explains its involatility and insolubility as well as high heat of formation. Each aluminium atom is surrounded by six fluorine atoms in a distorted octahedral arrangement, with each fluorine atom being shared between the corners of two octahedra. Such {AlF6} units also exist in complex fluorides such as cryolite, Na3AlF6.[f] AlF3 melts at 1,290 °C (2,354 °F) and is made by reaction of aluminium oxide with hydrogen fluoride gas at 700 °C (1,300 °F).[42]

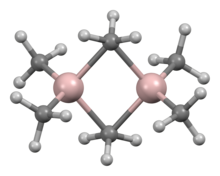

With heavier halides, the coordination numbers are lower. The other trihalides are dimeric or polymeric with tetrahedral four-coordinate aluminium centers.[g] Aluminium trichloride (AlCl3) has a layered polymeric structure below its melting point of 192.4 °C (378 °F) but transforms on melting to Al2Cl6 dimers. At higher temperatures those increasingly dissociate into trigonal planar AlCl3 monomers similar to the structure of BCl3. Aluminium tribromide and aluminium triiodide form Al2X6 dimers in all three phases and hence do not show such significant changes of properties upon phase change.[42] These materials are prepared by treating aluminium metal with the halogen. The aluminium trihalides form many addition compounds or complexes; their Lewis acidic nature makes them useful as catalysts for the Friedel–Crafts reactions. Aluminium trichloride has major industrial uses involving this reaction, such as in the manufacture of anthraquinones and styrene; it is also often used as the precursor for many other aluminium compounds and as a reagent for converting nonmetal fluorides into the corresponding chlorides (a transhalogenation reaction).[42]

Aluminium forms one stable oxide with the chemical formula Al2O3, commonly called alumina.[43] It can be found in nature in the mineral corundum, α-alumina;[44] there is also a γ-alumina phase.[8] Its crystalline form, corundum, is very hard (Mohs hardness 9), has a high melting point of 2,045 °C (3,713 °F), has very low volatility, is chemically inert, and a good electrical insulator, it is often used in abrasives (such as toothpaste), as a refractory material, and in ceramics, as well as being the starting material for the electrolytic production of aluminium metal. Sapphire and ruby are impure corundum contaminated with trace amounts of other metals.[8] The two main oxide-hydroxides, AlO(OH), are boehmite and diaspore. There are three main trihydroxides: bayerite, gibbsite, and nordstrandite, which differ in their crystalline structure (polymorphs). Many other intermediate and related structures are also known.[8] Most are produced from ores by a variety of wet processes using acid and base. Heating the hydroxides leads to formation of corundum. These materials are of central importance to the production of aluminium and are themselves extremely useful. Some mixed oxide phases are also very useful, such as spinel (MgAl2O4), Na-β-alumina (NaAl11O17), and tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6, an important mineral phase in Portland cement).[8]

The only stable chalcogenides under normal conditions are aluminium sulfide (Al2S3), selenide (Al2Se3), and telluride (Al2Te3). All three are prepared by direct reaction of their elements at about 1,000 °C (1,800 °F) and quickly hydrolyze completely in water to yield aluminium hydroxide and the respective hydrogen chalcogenide. As aluminium is a small atom relative to these chalcogens, these have four-coordinate tetrahedral aluminium with various polymorphs having structures related to wurtzite, with two-thirds of the possible metal sites occupied either in an orderly (α) or random (β) fashion; the sulfide also has a γ form related to γ-alumina, and an unusual high-temperature hexagonal form where half the aluminium atoms have tetrahedral four-coordination and the other half have trigonal bipyramidal five-coordination. [45]

Four pnictides – aluminium nitride (AlN), aluminium phosphide (AlP), aluminium arsenide (AlAs), and aluminium antimonide (AlSb) – are known. They are all III-V semiconductors isoelectronic to silicon and germanium, all of which but AlN have the zinc blende structure. All four can be made by high-temperature (and possibly high-pressure) direct reaction of their component elements.[45]

Aluminium alloys well with most other metals (with the exception of most alkali metals and group 13 metals) and over 150 intermetallics with other metals are known. Preparation involves heating fixed metals together in certain proportion, followed by gradual cooling and annealing. Bonding in them is predominantly metallic and the crystal structure primarily depends on efficiency of packing.[46]

There are few compounds with lower oxidation states. A few aluminium(I) compounds exist: AlF, AlCl, AlBr, and AlI exist in the gaseous phase when the respective trihalide is heated with aluminium, and at cryogenic temperatures.[42] A stable derivative of aluminium monoiodide is the cyclic adduct formed with triethylamine, Al4I4(NEt3)4. Al2O and Al2S also exist but are very unstable.[47] Very simple aluminium(II) compounds are invoked or observed in the reactions of Al metal with oxidants. For example, aluminium monoxide, AlO, has been detected in the gas phase after explosion[48] and in stellar absorption spectra.[49] More thoroughly investigated are compounds of the formula R4Al2 which contain an Al–Al bond and where R is a large organic ligand.[50]

Organoaluminium compounds and related hydrides

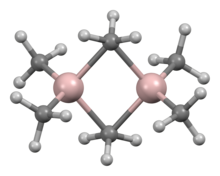

A variety of compounds of empirical formula AlR3 and AlR1.5Cl1.5 exist.[51] The aluminium trialkyls and triaryls are reactive, volatile, and colorless liquids or low-melting solids. They catch fire spontaneously in air and react with water, thus necessitating precautions when handling them. They often form dimers, unlike their boron analogues, but this tendency diminishes for branched-chain alkyls (e.g. Pri, Bui, Me3CCH2); for example, triisobutylaluminium exists as an equilibrium mixture of the monomer and dimer.[52][53] These dimers, such as trimethylaluminium (Al2Me6), usually feature tetrahedral Al centers formed by dimerization with some alkyl group bridging between both aluminium atoms. They are hard acids and react readily with ligands, forming adducts. In industry, they are mostly used in alkene insertion reactions, as discovered by Karl Ziegler, most importantly in «growth reactions» that form long-chain unbranched primary alkenes and alcohols, and in the low-pressure polymerization of ethene and propene. There are also some heterocyclic and cluster organoaluminium compounds involving Al–N bonds.[52]

The industrially most important aluminium hydride is lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4), which is used in as a reducing agent in organic chemistry. It can be produced from lithium hydride and aluminium trichloride.[54] The simplest hydride, aluminium hydride or alane, is not as important. It is a polymer with the formula (AlH3)n, in contrast to the corresponding boron hydride that is a dimer with the formula (BH3)2.[54]

Natural occurrence

Space

Aluminium’s per-particle abundance in the Solar System is 3.15 ppm (parts per million).[55][h] It is the twelfth most abundant of all elements and third most abundant among the elements that have odd atomic numbers, after hydrogen and nitrogen.[55] The only stable isotope of aluminium, 27Al, is the eighteenth most abundant nucleus in the Universe. It is created almost entirely after fusion of carbon in massive stars that will later become Type II supernovas: this fusion creates 26Mg, which, upon capturing free protons and neutrons becomes aluminium. Some smaller quantities of 27Al are created in hydrogen burning shells of evolved stars, where 26Mg can capture free protons.[56] Essentially all aluminium now in existence is 27Al. 26Al was present in the early Solar System with abundance of 0.005% relative to 27Al but its half-life of 728,000 years is too short for any original nuclei to survive; 26Al is therefore extinct.[56] Unlike for 27Al, hydrogen burning is the primary source of 26Al, with the nuclide emerging after a nucleus of 25Mg catches a free proton. However, the trace quantities of 26Al that do exist are the most common gamma ray emitter in the interstellar gas;[56] if the original 26Al were still present, gamma ray maps of the Milky Way would be brighter.[56]

Earth

Bauxite, a major aluminium ore. The red-brown color is due to the presence of iron oxide minerals.

Overall, the Earth is about 1.59% aluminium by mass (seventh in abundance by mass).[57] Aluminium occurs in greater proportion in the Earth’s crust than in the Universe at large, because aluminium easily forms the oxide and becomes bound into rocks and stays in the Earth’s crust, while less reactive metals sink to the core.[56] In the Earth’s crust, aluminium is the most abundant metallic element (8.23% by mass[26]) and the third most abundant of all elements (after oxygen and silicon).[58] A large number of silicates in the Earth’s crust contain aluminium.[59] In contrast, the Earth’s mantle is only 2.38% aluminium by mass.[60] Aluminium also occurs in seawater at a concentration of 2 μg/kg.[26]

Because of its strong affinity for oxygen, aluminium is almost never found in the elemental state; instead it is found in oxides or silicates. Feldspars, the most common group of minerals in the Earth’s crust, are aluminosilicates. Aluminium also occurs in the minerals beryl, cryolite, garnet, spinel, and turquoise.[61] Impurities in Al2O3, such as chromium and iron, yield the gemstones ruby and sapphire, respectively.[62] Native aluminium metal is extremely rare and can only be found as a minor phase in low oxygen fugacity environments, such as the interiors of certain volcanoes.[63] Native aluminium has been reported in cold seeps in the northeastern continental slope of the South China Sea. It is possible that these deposits resulted from bacterial reduction of tetrahydroxoaluminate Al(OH)4−.[64]

Although aluminium is a common and widespread element, not all aluminium minerals are economically viable sources of the metal. Almost all metallic aluminium is produced from the ore bauxite (AlOx(OH)3–2x). Bauxite occurs as a weathering product of low iron and silica bedrock in tropical climatic conditions.[65] In 2017, most bauxite was mined in Australia, China, Guinea, and India.[66]

History

Friedrich Wöhler, the chemist who first thoroughly described metallic elemental aluminium

The history of aluminium has been shaped by usage of alum. The first written record of alum, made by Greek historian Herodotus, dates back to the 5th century BCE.[67] The ancients are known to have used alum as a dyeing mordant and for city defense.[67] After the Crusades, alum, an indispensable good in the European fabric industry,[68] was a subject of international commerce;[69] it was imported to Europe from the eastern Mediterranean until the mid-15th century.[70]

The nature of alum remained unknown. Around 1530, Swiss physician Paracelsus suggested alum was a salt of an earth of alum.[71] In 1595, German doctor and chemist Andreas Libavius experimentally confirmed this.[72] In 1722, German chemist Friedrich Hoffmann announced his belief that the base of alum was a distinct earth.[73] In 1754, German chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf synthesized alumina by boiling clay in sulfuric acid and subsequently adding potash.[73]

Attempts to produce aluminium metal date back to 1760.[74] The first successful attempt, however, was completed in 1824 by Danish physicist and chemist Hans Christian Ørsted. He reacted anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium amalgam, yielding a lump of metal looking similar to tin.[75][76][77] He presented his results and demonstrated a sample of the new metal in 1825.[78][79] In 1827, German chemist Friedrich Wöhler repeated Ørsted’s experiments but did not identify any aluminium.[80] (The reason for this inconsistency was only discovered in 1921.)[81] He conducted a similar experiment in the same year by mixing anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium and produced a powder of aluminium.[77] In 1845, he was able to produce small pieces of the metal and described some physical properties of this metal.[81] For many years thereafter, Wöhler was credited as the discoverer of aluminium.[82]

As Wöhler’s method could not yield great quantities of aluminium, the metal remained rare; its cost exceeded that of gold.[80] The first industrial production of aluminium was established in 1856 by French chemist Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville and companions.[83] Deville had discovered that aluminium trichloride could be reduced by sodium, which was more convenient and less expensive than potassium, which Wöhler had used.[84] Even then, aluminium was still not of great purity and produced aluminium differed in properties by sample.[85] Because of its electricity-conducting capacity, aluminium was used as the cap of the Washington Monument, completed in 1885. The tallest building in the world at the time, the non-corroding metal cap was intended to serve as a lightning rod peak.

The first industrial large-scale production method was independently developed in 1886 by French engineer Paul Héroult and American engineer Charles Martin Hall; it is now known as the Hall–Héroult process.[86] The Hall–Héroult process converts alumina into metal. Austrian chemist Carl Joseph Bayer discovered a way of purifying bauxite to yield alumina, now known as the Bayer process, in 1889.[87] Modern production of the aluminium metal is based on the Bayer and Hall–Héroult processes.[88]

Prices of aluminium dropped and aluminium became widely used in jewelry, everyday items, eyeglass frames, optical instruments, tableware, and foil in the 1890s and early 20th century. Aluminium’s ability to form hard yet light alloys with other metals provided the metal with many uses at the time.[89] During World War I, major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light strong airframes;[90] during World War II, demand by major governments for aviation was even higher.[91][92][93]

By the mid-20th century, aluminium had become a part of everyday life and an essential component of housewares.[94] In 1954, production of aluminium surpassed that of copper,[i] historically second in production only to iron,[97] making it the most produced non-ferrous metal. During the mid-20th century, aluminium emerged as a civil engineering material, with building applications in both basic construction and interior finish work,[98] and increasingly being used in military engineering, for both airplanes and land armor vehicle engines.[99] Earth’s first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two separate aluminium semi-spheres joined and all subsequent space vehicles have used aluminium to some extent.[88] The aluminium can was invented in 1956 and employed as a storage for drinks in 1958.[100]

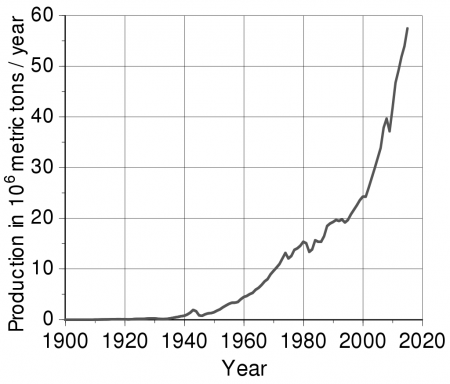

World production of aluminium since 1900

Throughout the 20th century, the production of aluminium rose rapidly: while the world production of aluminium in 1900 was 6,800 metric tons, the annual production first exceeded 100,000 metric tons in 1916; 1,000,000 tons in 1941; 10,000,000 tons in 1971.[95] In the 1970s, the increased demand for aluminium made it an exchange commodity; it entered the London Metal Exchange, the oldest industrial metal exchange in the world, in 1978.[88] The output continued to grow: the annual production of aluminium exceeded 50,000,000 metric tons in 2013.[95]

The real price for aluminium declined from $14,000 per metric ton in 1900 to $2,340 in 1948 (in 1998 United States dollars).[95] Extraction and processing costs were lowered over technological progress and the scale of the economies. However, the need to exploit lower-grade poorer quality deposits and the use of fast increasing input costs (above all, energy) increased the net cost of aluminium;[101] the real price began to grow in the 1970s with the rise of energy cost.[102] Production moved from the industrialized countries to countries where production was cheaper.[103] Production costs in the late 20th century changed because of advances in technology, lower energy prices, exchange rates of the United States dollar, and alumina prices.[104] The BRIC countries’ combined share in primary production and primary consumption grew substantially in the first decade of the 21st century.[105] China is accumulating an especially large share of the world’s production thanks to an abundance of resources, cheap energy, and governmental stimuli;[106] it also increased its consumption share from 2% in 1972 to 40% in 2010.[107] In the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging.[108] In 2021, prices for industrial metals such as aluminium have soared to near-record levels as energy shortages in China drive up costs for electricity.[109]

Etymology

The names aluminium and aluminum are derived from the word alumine, an obsolete term for alumina,[j] a naturally occurring oxide of aluminium.[111] Alumine was borrowed from French, which in turn derived it from alumen, the classical Latin name for alum, the mineral from which it was collected.[112] The Latin word alumen stems from the Proto-Indo-European root *alu- meaning «bitter» or «beer».[113]

1897 American advertisement featuring the aluminum spelling

Origins

British chemist Humphry Davy, who performed a number of experiments aimed to isolate the metal, is credited as the person who named the element. The first name proposed for the metal to be isolated from alum was alumium, which Davy suggested in an 1808 article on his electrochemical research, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[114] It appeared that the name was created from the English word alum and the Latin suffix -ium; but it was customary then to give elements names originating in Latin, so that this name was not adopted universally. This name was criticized by contemporary chemists from France, Germany, and Sweden, who insisted the metal should be named for the oxide, alumina, from which it would be isolated.[115] The English name alum does not come directly from Latin, whereas alumine/alumina obviously comes from the Latin word alumen (upon declension, alumen changes to alumin-).

One example was Essai sur la Nomenclature chimique (July 1811), written in French by a Swedish chemist, Jöns Jacob Berzelius, in which the name aluminium is given to the element that would be synthesized from alum.[116][k] (Another article in the same journal issue also gives the name aluminium to the metal whose oxide is the basis of sapphire.)[118] A January 1811 summary of one of Davy’s lectures at the Royal Society mentioned the name aluminium as a possibility.[119] The next year, Davy published a chemistry textbook in which he used the spelling aluminum.[120] Both spellings have coexisted since. Their usage is regional: aluminum dominates in the United States and Canada; aluminium, in the rest of the English-speaking world.[121]

Spelling

In 1812, a British scientist, Thomas Young,[122] wrote an anonymous review of Davy’s book, in which he proposed the name aluminium instead of aluminum, which he thought had a «less classical sound».[123] This name did catch on: although the -um spelling was occasionally used in Britain, the American scientific language used -ium from the start.[124] Most scientists throughout the world used -ium in the 19th century;[121] and it was entrenched in many other European languages, such as French, German, and Dutch.[l] In 1828, an American lexicographer, Noah Webster, entered only the aluminum spelling in his American Dictionary of the English Language.[125] In the 1830s, the -um spelling gained usage in the United States; by the 1860s, it had become the more common spelling there outside science.[124] In 1892, Hall used the -um spelling in his advertising handbill for his new electrolytic method of producing the metal, despite his constant use of the -ium spelling in all the patents he filed between 1886 and 1903: it is unknown whether this spelling was introduced by mistake or intentionally; but Hall preferred aluminum since its introduction because it resembled platinum, the name of a prestigious metal.[126] By 1890, both spellings had been common in the United States, the -ium spelling being slightly more common; by 1895, the situation had reversed; by 1900, aluminum had become twice as common as aluminium; in the next decade, the -um spelling dominated American usage. In 1925, the American Chemical Society adopted this spelling.[121]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted aluminium as the standard international name for the element in 1990.[127] In 1993, they recognized aluminum as an acceptable variant;[127] the most recent 2005 edition of the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry also acknowledges this spelling.[128] IUPAC official publications use the -ium spelling as primary, and they list both where it is appropriate.[m]

Production and refinement

The production of aluminium starts with the extraction of bauxite rock from the ground. The bauxite is processed and transformed using the Bayer process into alumina, which is then processed using the Hall–Héroult process, resulting in the final aluminium metal.

Aluminium production is highly energy-consuming, and so the producers tend to locate smelters in places where electric power is both plentiful and inexpensive.[130] As of 2019, the world’s largest smelters of aluminium are located in China, India, Russia, Canada, and the United Arab Emirates,[131] while China is by far the top producer of aluminium with a world share of fifty-five percent.

According to the International Resource Panel’s Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of aluminium in use in society (i.e. in cars, buildings, electronics, etc.) is 80 kg (180 lb). Much of this is in more-developed countries (350–500 kg (770–1,100 lb) per capita) rather than less-developed countries (35 kg (77 lb) per capita).[132]

Bayer process

Bauxite is converted to alumina by the Bayer process. Bauxite is blended for uniform composition and then is ground. The resulting slurry is mixed with a hot solution of sodium hydroxide; the mixture is then treated in a digester vessel at a pressure well above atmospheric, dissolving the aluminium hydroxide in bauxite while converting impurities into relatively insoluble compounds:[133]

Al(OH)3 + Na+ + OH− → Na+ + [Al(OH)4]−

After this reaction, the slurry is at a temperature above its atmospheric boiling point. It is cooled by removing steam as pressure is reduced. The bauxite residue is separated from the solution and discarded. The solution, free of solids, is seeded with small crystals of aluminium hydroxide; this causes decomposition of the [Al(OH)4]− ions to aluminium hydroxide. After about half of aluminium has precipitated, the mixture is sent to classifiers. Small crystals of aluminium hydroxide are collected to serve as seeding agents; coarse particles are converted to alumina by heating; the excess solution is removed by evaporation, (if needed) purified, and recycled.[133]

Hall–Héroult process

The conversion of alumina to aluminium metal is achieved by the Hall–Héroult process. In this energy-intensive process, a solution of alumina in a molten (950 and 980 °C (1,740 and 1,800 °F)) mixture of cryolite (Na3AlF6) with calcium fluoride is electrolyzed to produce metallic aluminium. The liquid aluminium metal sinks to the bottom of the solution and is tapped off, and usually cast into large blocks called aluminium billets for further processing.[39]

Anodes of the electrolysis cell are made of carbon—the most resistant material against fluoride corrosion—and either bake at the process or are prebaked. The former, also called Söderberg anodes, are less power-efficient and fumes released during baking are costly to collect, which is why they are being replaced by prebaked anodes even though they save the power, energy, and labor to prebake the cathodes. Carbon for anodes should be preferably pure so that neither aluminium nor the electrolyte is contaminated with ash. Despite carbon’s resistivity against corrosion, it is still consumed at a rate of 0.4–0.5 kg per each kilogram of produced aluminium. Cathodes are made of anthracite; high purity for them is not required because impurities leach only very slowly. The cathode is consumed at a rate of 0.02–0.04 kg per each kilogram of produced aluminium. A cell is usually terminated after 2–6 years following a failure of the cathode.[39]

The Hall–Heroult process produces aluminium with a purity of above 99%. Further purification can be done by the Hoopes process. This process involves the electrolysis of molten aluminium with a sodium, barium, and aluminium fluoride electrolyte. The resulting aluminium has a purity of 99.99%.[39][134]

Electric power represents about 20 to 40% of the cost of producing aluminium, depending on the location of the smelter. Aluminium production consumes roughly 5% of electricity generated in the United States.[127] Because of this, alternatives to the Hall–Héroult process have been researched, but none has turned out to be economically feasible.[39]

Recycling

Common bins for recyclable waste along with a bin for unrecyclable waste. The bin with a yellow top is labeled «aluminum». Rhodes, Greece.

Recovery of the metal through recycling has become an important task of the aluminium industry. Recycling was a low-profile activity until the late 1960s, when the growing use of aluminium beverage cans brought it to public awareness.[135] Recycling involves melting the scrap, a process that requires only 5% of the energy used to produce aluminium from ore, though a significant part (up to 15% of the input material) is lost as dross (ash-like oxide).[136] An aluminium stack melter produces significantly less dross, with values reported below 1%.[137]

White dross from primary aluminium production and from secondary recycling operations still contains useful quantities of aluminium that can be extracted industrially. The process produces aluminium billets, together with a highly complex waste material. This waste is difficult to manage. It reacts with water, releasing a mixture of gases (including, among others, hydrogen, acetylene, and ammonia), which spontaneously ignites on contact with air;[138] contact with damp air results in the release of copious quantities of ammonia gas. Despite these difficulties, the waste is used as a filler in asphalt and concrete.[139]

Applications

Metal

The global production of aluminium in 2016 was 58.8 million metric tons. It exceeded that of any other metal except iron (1,231 million metric tons).[140][141]

Aluminium is almost always alloyed, which markedly improves its mechanical properties, especially when tempered. For example, the common aluminium foils and beverage cans are alloys of 92% to 99% aluminium.[142] The main alloying agents are copper, zinc, magnesium, manganese, and silicon (e.g., duralumin) with the levels of other metals in a few percent by weight.[143] Aluminium, both wrought and cast, has been alloyed with: manganese, silicon, magnesium, copper and zinc among others.[144] For example, the Kynal family of alloys was developed by the British chemical manufacturer Imperial Chemical Industries.

The major uses for aluminium metal are in:[145]

- Transportation (automobiles, aircraft, trucks, railway cars, marine vessels, bicycles, spacecraft, etc.). Aluminium is used because of its low density;

- Packaging (cans, foil, frame, etc.). Aluminium is used because it is non-toxic (see below), non-adsorptive, and splinter-proof;

- Building and construction (windows, doors, siding, building wire, sheathing, roofing, etc.). Since steel is cheaper, aluminium is used when lightness, corrosion resistance, or engineering features are important;

- Electricity-related uses (conductor alloys, motors, and generators, transformers, capacitors, etc.). Aluminium is used because it is relatively cheap, highly conductive, has adequate mechanical strength and low density, and resists corrosion;

- A wide range of household items, from cooking utensils to furniture. Low density, good appearance, ease of fabrication, and durability are the key factors of aluminium usage;

- Machinery and equipment (processing equipment, pipes, tools). Aluminium is used because of its corrosion resistance, non-pyrophoricity, and mechanical strength.

- Portable computer cases. Currently rarely used without alloying,[146] but aluminium can be recycled and clean aluminium has residual market value: for example, the used beverage can (UBC) material was used to encase the electronic components of MacBook Air laptop, Pixel 5 smartphone or Summit Lite smartwatch.[147][148][149]

Compounds

The great majority (about 90%) of aluminium oxide is converted to metallic aluminium.[133] Being a very hard material (Mohs hardness 9),[150] alumina is widely used as an abrasive;[151] being extraordinarily chemically inert, it is useful in highly reactive environments such as high pressure sodium lamps.[152] Aluminium oxide is commonly used as a catalyst for industrial processes;[133] e.g. the Claus process to convert hydrogen sulfide to sulfur in refineries and to alkylate amines.[153][154] Many industrial catalysts are supported by alumina, meaning that the expensive catalyst material is dispersed over a surface of the inert alumina.[155] Another principal use is as a drying agent or absorbent.[133][156]

Laser deposition of alumina on a substrate

Several sulfates of aluminium have industrial and commercial application. Aluminium sulfate (in its hydrate form) is produced on the annual scale of several millions of metric tons.[157] About two-thirds is consumed in water treatment.[157] The next major application is in the manufacture of paper.[157] It is also used as a mordant in dyeing, in pickling seeds, deodorizing of mineral oils, in leather tanning, and in production of other aluminium compounds.[157] Two kinds of alum, ammonium alum and potassium alum, were formerly used as mordants and in leather tanning, but their use has significantly declined following availability of high-purity aluminium sulfate.[157] Anhydrous aluminium chloride is used as a catalyst in chemical and petrochemical industries, the dyeing industry, and in synthesis of various inorganic and organic compounds.[157] Aluminium hydroxychlorides are used in purifying water, in the paper industry, and as antiperspirants.[157] Sodium aluminate is used in treating water and as an accelerator of solidification of cement.[157]

Many aluminium compounds have niche applications, for example:

- Aluminium acetate in solution is used as an astringent.[158]

- Aluminium phosphate is used in the manufacture of glass, ceramic, pulp and paper products, cosmetics, paints, varnishes, and in dental cement.[159]

- Aluminium hydroxide is used as an antacid, and mordant; it is used also in water purification, the manufacture of glass and ceramics, and in the waterproofing of fabrics.[160][161]

- Lithium aluminium hydride is a powerful reducing agent used in organic chemistry.[162][163]

- Organoaluminiums are used as Lewis acids and co-catalysts.[164]

- Methylaluminoxane is a co-catalyst for Ziegler–Natta olefin polymerization to produce vinyl polymers such as polyethene.[165]

- Aqueous aluminium ions (such as aqueous aluminium sulfate) are used to treat against fish parasites such as Gyrodactylus salaris.[166]

- In many vaccines, certain aluminium salts serve as an immune adjuvant (immune response booster) to allow the protein in the vaccine to achieve sufficient potency as an immune stimulant.[167]

Aluminized substrates

Aluminizing is the process of coating a structure or material with a thin layer of aluminium. It is done to impart specific traits that the underlying substrate lacks, such as a certain chemical or physical property. Aluminized materials include:

- Aluminized steel, for corrosion resistance and other properties

- Aluminized screen, for display devices

- Aluminized cloth, to reflect heat

- Aluminized mylar, to reflect heat

Biology

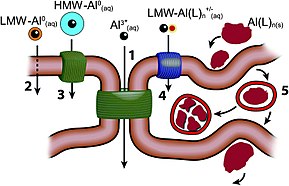

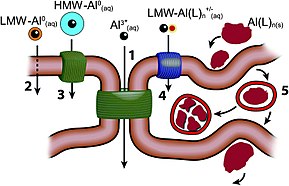

Schematic of aluminium absorption by human skin.[168]

Despite its widespread occurrence in the Earth’s crust, aluminium has no known function in biology.[39] At pH 6–9 (relevant for most natural waters), aluminium precipitates out of water as the hydroxide and is hence not available; most elements behaving this way have no biological role or are toxic.[169] Aluminium sulfate has an LD50 of 6207 mg/kg (oral, mouse), which corresponds to 435 grams for an 70 kg (150 lb) person.[39]

Toxicity

Aluminium is classified as a non-carcinogen by the United States Department of Health and Human Services.[170][n] A review published in 1988 said that there was little evidence that normal exposure to aluminium presents a risk to healthy adult,[173] and a 2014 multi-element toxicology review was unable to find deleterious effects of aluminium consumed in amounts not greater than 40 mg/day per kg of body mass.[170] Most aluminium consumed will leave the body in feces; most of the small part of it that enters the bloodstream, will be excreted via urine;[174] nevertheless some aluminium does pass the blood-brain barrier and is lodged preferentially in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.[175][176] Evidence published in 1989 indicates that, for Alzheimer’s patients, aluminium may act by electrostatically crosslinking proteins, thus down-regulating genes in the superior temporal gyrus.[177]

Effects

Aluminium, although rarely, can cause vitamin D-resistant osteomalacia, erythropoietin-resistant microcytic anemia, and central nervous system alterations. People with kidney insufficiency are especially at a risk.[170] Chronic ingestion of hydrated aluminium silicates (for excess gastric acidity control) may result in aluminium binding to intestinal contents and increased elimination of other metals, such as iron or zinc; sufficiently high doses (>50 g/day) can cause anemia.[170]

There are five major aluminium forms absorbed by human body: the free solvated trivalent cation (Al3+(aq)); low-molecular-weight, neutral, soluble complexes (LMW-Al0(aq)); high-molecular-weight, neutral, soluble complexes (HMW-Al0(aq)); low-molecular-weight, charged, soluble complexes (LMW-Al(L)n+/−(aq)); nano and micro-particulates (Al(L)n(s)). They are transported across cell membranes or cell epi-/endothelia through five major routes: (1) paracellular; (2) transcellular; (3) active transport; (4) channels; (5) adsorptive or receptor-mediated endocytosis.[168]

During the 1988 Camelford water pollution incident people in Camelford had their drinking water contaminated with aluminium sulfate for several weeks. A final report into the incident in 2013 concluded it was unlikely that this had caused long-term health problems.[178]

Aluminium has been suspected of being a possible cause of Alzheimer’s disease,[179] but research into this for over 40 years has found, as of 2018, no good evidence of causal effect.[180][181]

Aluminium increases estrogen-related gene expression in human breast cancer cells cultured in the laboratory.[182] In very high doses, aluminium is associated with altered function of the blood–brain barrier.[183] A small percentage of people have contact allergies to aluminium and experience itchy red rashes, headache, muscle pain, joint pain, poor memory, insomnia, depression, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, or other symptoms upon contact with products containing aluminium.[185]

Exposure to powdered aluminium or aluminium welding fumes can cause pulmonary fibrosis.[186] Fine aluminium powder can ignite or explode, posing another workplace hazard.[187][188]

Exposure routes

Food is the main source of aluminium. Drinking water contains more aluminium than solid food;[170] however, aluminium in food may be absorbed more than aluminium from water.[189] Major sources of human oral exposure to aluminium include food (due to its use in food additives, food and beverage packaging, and cooking utensils), drinking water (due to its use in municipal water treatment), and aluminium-containing medications (particularly antacid/antiulcer and buffered aspirin formulations).[190] Dietary exposure in Europeans averages to 0.2–1.5 mg/kg/week but can be as high as 2.3 mg/kg/week.[170] Higher exposure levels of aluminium are mostly limited to miners, aluminium production workers, and dialysis patients.[191]

Consumption of antacids, antiperspirants, vaccines, and cosmetics provide possible routes of exposure.[192] Consumption of acidic foods or liquids with aluminium enhances aluminium absorption,[193] and maltol has been shown to increase the accumulation of aluminium in nerve and bone tissues.[194]

Treatment

In case of suspected sudden intake of a large amount of aluminium, the only treatment is deferoxamine mesylate which may be given to help eliminate aluminium from the body by chelation.[195][196] However, this should be applied with caution as this reduces not only aluminium body levels, but also those of other metals such as copper or iron.[195]

Environmental effects

«Bauxite tailings» storage facility in Stade, Germany. The aluminium industry generates about 70 million tons of this waste annually.

High levels of aluminium occur near mining sites; small amounts of aluminium are released to the environment at the coal-fired power plants or incinerators.[197] Aluminium in the air is washed out by the rain or normally settles down but small particles of aluminium remain in the air for a long time.[197]

Acidic precipitation is the main natural factor to mobilize aluminium from natural sources[170] and the main reason for the environmental effects of aluminium;[198] however, the main factor of presence of aluminium in salt and freshwater are the industrial processes that also release aluminium into air.[170]

In water, aluminium acts as a toxiс agent on gill-breathing animals such as fish when the water is acidic, in which aluminium may precipitate on gills,[199] which causes loss of plasma- and hemolymph ions leading to osmoregulatory failure.[198] Organic complexes of aluminium may be easily absorbed and interfere with metabolism in mammals and birds, even though this rarely happens in practice.[198]

Aluminium is primary among the factors that reduce plant growth on acidic soils. Although it is generally harmless to plant growth in pH-neutral soils, in acid soils the concentration of toxic Al3+ cations increases and disturbs root growth and function.[200][201][202][203] Wheat has developed a tolerance to aluminium, releasing organic compounds that bind to harmful aluminium cations. Sorghum is believed to have the same tolerance mechanism.[204]

Aluminium production possesses its own challenges to the environment on each step of the production process. The major challenge is the greenhouse gas emissions.[191] These gases result from electrical consumption of the smelters and the byproducts of processing. The most potent of these gases are perfluorocarbons from the smelting process.[191] Released sulfur dioxide is one of the primary precursors of acid rain.[191]

Biodegradation of metallic aluminium is extremely rare; most aluminium-corroding organisms do not directly attack or consume the aluminium, but instead produce corrosive wastes.[205][206] The fungus Geotrichum candidum can consume the aluminium in compact discs.[207][208][209] The bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Cladosporium resinae are commonly detected in aircraft fuel tanks that use kerosene-based fuels (not avgas), and laboratory cultures can degrade aluminium.[210]

See also

- Aluminium granules

- Aluminium joining

- Aluminium–air battery

- Panel edge staining

- Quantum clock

Notes

- ^ Davy’s 1812 written usage of the word aluminum was predated by other authors’ usage of aluminium. However, Davy is often mentioned as the person who named the element; he was the first to coin a name for aluminium: he used alumium in 1808. Other authors did not accept that name, choosing aluminium instead. See below for more details.

- ^ No elements with odd atomic numbers have more than two stable isotopes; even-numbered elements have multiple stable isotopes, with tin (element 50) having the highest number of stable isotopes of all elements, ten. The single exception is beryllium which is even-numbered but has only one stable isotope.[7] See Even and odd atomic nuclei for more details.

- ^ Most other metals have greater standard atomic weights: for instance, that of iron is 55.8; copper 63.5; lead 207.2.[9] which has consequences for the element’s properties (see below)

- ^ The two sides of aluminium foil differ in their luster: one is shiny and the other is dull. The difference is due to the small mechanical damage on the surface of dull side arising from the technological process of aluminium foil manufacturing.[19] Both sides reflect similar amounts of visible light, but the shiny side reflects a far greater share of visible light specularly whereas the dull side almost exclusively diffuses light. Both sides of aluminium foil serve as good reflectors (approximately 86%) of visible light and an excellent reflector (as much as 97%) of medium and far infrared radiation.[20]

- ^ In fact, aluminium’s electropositive behavior, high affinity for oxygen, and highly negative standard electrode potential are all better aligned with those of scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, and actinium, which like aluminium have three valence electrons outside a noble gas core; this series shows continuous trends whereas those of group 13 is broken by the first added d-subshell in gallium and the resulting d-block contraction and the first added f-subshell in thallium and the resulting lanthanide contraction.[32]

- ^ These should not be considered as [AlF6]3− complex anions as the Al–F bonds are not significantly different in type from the other M–F bonds.[42]

- ^ Such differences in coordination between the fluorides and heavier halides are not unusual, occurring in SnIV and BiIII, for example; even bigger differences occur between CO2 and SiO2.[42]

- ^ Abundances in the source are listed relative to silicon rather than in per-particle notation. The sum of all elements per 106 parts of silicon is 2.6682×1010 parts; aluminium comprises 8.410×104 parts.

- ^ Compare annual statistics of aluminium[95] and copper[96] production by USGS.

- ^ The spelling alumine comes from French, whereas the spelling alumina comes from Latin.[110]

- ^ Davy discovered several other elements, including those he named sodium and potassium, after the English words soda and potash. Berzelius referred to them as to natrium and kalium. Berzelius’s suggestion was expanded in 1814[117] with his proposed system of one or two-letter chemical symbols, which are used up to the present day; sodium and potassium have the symbols Na and K, respectively, after their Latin names.

- ^ Some European languages, like Spanish or Italian, use a different suffix from the Latin -um/-ium to form a name of a metal, some, like Polish or Czech, have a different base for the name of the element, and some, like Russian or Greek, don’t use the Latin script altogether.

- ^ For instance, see the November–December 2013 issue of Chemistry International: in a table of (some) elements, the element is listed as «aluminium (aluminum)».[129]

- ^ While aluminium per se is not carcinogenic, Söderberg aluminium production is, as is noted by the International Agency for Research on Cancer,[171] likely due to exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[172]

References

- ^ «aluminum». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Aluminium». CIAAW. 2017.

- ^ Unstable carbonyl of Al(0) has been detected in reaction of Al2(CH3)6 with carbon monoxide; see Sanchez, Ramiro; Arrington, Caleb; Arrington Jr., C. A. (1 December 1989). «Reaction of trimethylaluminum with carbon monoxide in low-temperature matrixes». American Chemical Society. 111 (25): 9110-9111. doi:10.1021/ja00207a023.

- ^ Dohmeier, C.; Loos, D.; Schnöckel, H. (1996). «Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Compounds: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactions». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 35 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1002/anie.199601291.

- ^ D. C. Tyte (1964). «Red (B2Π–A2σ) Band System of Aluminium Monoxide». Nature. 202 (4930): 383. Bibcode:1964Natur.202..383T. doi:10.1038/202383a0. S2CID 4163250.

- ^

Lide, D. R. (2000). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds» (PDF). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 0849304814. - ^ a b IAEA – Nuclear Data Section (2017). «Livechart – Table of Nuclides – Nuclear structure and decay data». www-nds.iaea.org. International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 242–252.

- ^ Meija, Juris; et al. (2016). «Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)». Pure and Applied Chemistry. 88 (3): 265–91. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

- ^ «Aluminium». The Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Dickin, A.P. (2005). «In situ Cosmogenic Isotopes». Radiogenic Isotope Geology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53017-0. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ Dodd, R.T. (1986). Thunderstones and Shooting Stars. Harvard University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-674-89137-1.

- ^ Dean 1999, p. 4.2.

- ^ Dean 1999, p. 4.6.

- ^ Dean 1999, p. 4.29.

- ^ a b Dean 1999, p. 4.30.

- ^ a b Enghag, Per (2008). Encyclopedia of the Elements: Technical Data – History – Processing – Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 139, 819, 949. ISBN 978-3-527-61234-5. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 222–4

- ^ «Heavy Duty Foil». Reynolds Kitchens. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Pozzobon, V.; Levasseur, W.; Do, Kh.-V.; et al. (2020). «Household aluminum foil matte and bright side reflectivity measurements: Application to a photobioreactor light concentrator design». Biotechnology Reports. 25: e00399. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00399. PMC 6906702. PMID 31867227.

- ^ Lide 2004, p. 4-3.

- ^ Puchta, Ralph (2011). «A brighter beryllium». Nature Chemistry. 3 (5): 416. Bibcode:2011NatCh…3..416P. doi:10.1038/nchem.1033. PMID 21505503.

- ^ Davis 1999, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Davis 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b Polmear, I.J. (1995). Light Alloys: Metallurgy of the Light Metals (3 ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-340-63207-9.

- ^ a b c Cardarelli, François (2008). Materials handbook : a concise desktop reference (2nd ed.). London: Springer. pp. 158–163. ISBN 978-1-84628-669-8. OCLC 261324602.

- ^ a b Davis 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Davis 1999, pp. 2–3.

- ^

Cochran, J.F.; Mapother, D.E. (1958). «Superconducting Transition in Aluminum». Physical Review. 111 (1): 132–142. Bibcode:1958PhRv..111..132C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.111.132. - ^ Schmitz 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Schmitz 2006, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 224–227.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 112–113.

- ^ King 1995, p. 241.

- ^ King 1995, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Hatch, John E. (1984). Aluminum : properties and physical metallurgy. Metals Park, Ohio: American Society for Metals, Aluminum Association. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-61503-169-6. OCLC 759213422.

- ^ Vargel, Christian (2004) [French edition published 1999]. Corrosion of Aluminium. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044495-6. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016.

- ^ Macleod, H.A. (2001). Thin-film optical filters. CRC Press. p. 158159. ISBN 978-0-7503-0688-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frank, W.B. (2009). «Aluminum». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_459.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b Beal, Roy E. (1999). Engine Coolant Testing : Fourth Volume. ASTM International. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8031-2610-7. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- ^ *Baes, C. F.; Mesmer, R. E. (1986) [1976]. The Hydrolysis of Cations. Robert E. Krieger. ISBN 978-0-89874-892-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 233–237.

- ^ Eastaugh, Nicholas; Walsh, Valentine; Chaplin, Tracey; Siddall, Ruth (2008). Pigment Compendium. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-37393-0. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Roscoe, Henry Enfield; Schorlemmer, Carl (1913). A treatise on chemistry. Macmillan. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 252–257.

- ^ Downs, A. J. (1993). Chemistry of Aluminium, Gallium, Indium and Thallium. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7514-0103-5. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Dohmeier, C.; Loos, D.; Schnöckel, H. (1996). «Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Compounds: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactions». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 35 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1002/anie.199601291.

- ^ Tyte, D.C. (1964). «Red (B2Π–A2σ) Band System of Aluminium Monoxide». Nature. 202 (4930): 383–384. Bibcode:1964Natur.202..383T. doi:10.1038/202383a0. S2CID 4163250.

- ^ Merrill, P.W.; Deutsch, A.J.; Keenan, P.C. (1962). «Absorption Spectra of M-Type Mira Variables». The Astrophysical Journal. 136: 21. Bibcode:1962ApJ…136…21M. doi:10.1086/147348.

- ^ Uhl, W. (2004). «Organoelement Compounds Possessing Al–Al, Ga–Ga, In–In, and Tl–Tl Single Bonds». Organoelement Compounds Possessing Al–Al, Ga–Ga, In–In, and Tl–Tl Single Bonds. Advances in Organometallic Chemistry. Vol. 51. pp. 53–108. doi:10.1016/S0065-3055(03)51002-4. ISBN 978-0-12-031151-4.

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. (2006). Organometallics. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 257–67.

- ^ Smith, Martin B. (1970). «The monomer-dimer equilibria of liquid aluminum alkyls». Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 22 (2): 273–281. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)86043-X.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, pp. 227–232.

- ^ a b Lodders, K. (2003). «Solar System abundances and condensation temperatures of the elements» (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 591 (2): 1220–1247. Bibcode:2003ApJ…591.1220L. doi:10.1086/375492. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 42498829. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Clayton, D. (2003). Handbook of Isotopes in the Cosmos : Hydrogen to Gallium. Leiden: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–137. ISBN 978-0-511-67305-4. OCLC 609856530. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ William F McDonough The composition of the Earth. quake.mit.edu, archived by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 217–9

- ^ Wade, K.; Banister, A.J. (2016). The Chemistry of Aluminium, Gallium, Indium and Thallium: Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 1049. ISBN 978-1-4831-5322-3. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Palme, H.; O’Neill, Hugh St. C. (2005). «Cosmochemical Estimates of Mantle Composition» (PDF). In Carlson, Richard W. (ed.). The Mantle and Core. Elseiver. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Downs, A.J. (1993). Chemistry of Aluminium, Gallium, Indium and Thallium. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-7514-0103-5. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Kotz, John C.; Treichel, Paul M.; Townsend, John (2012). Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity. Cengage Learning. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-133-42007-1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Barthelmy, D. «Aluminum Mineral Data». Mineralogy Database. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Chen, Z.; Huang, Chi-Yue; Zhao, Meixun; Yan, Wen; Chien, Chih-Wei; Chen, Muhong; Yang, Huaping; Machiyama, Hideaki; Lin, Saulwood (2011). «Characteristics and possible origin of native aluminum in cold seep sediments from the northeastern South China Sea». Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 40 (1): 363–370. Bibcode:2011JAESc..40..363C. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.06.006.

- ^ Guilbert, J.F.; Park, C.F. (1986). The Geology of Ore Deposits. W.H. Freeman. pp. 774–795. ISBN 978-0-7167-1456-9.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (2018). «Bauxite and alumina» (PDF). Mineral Commodities Summaries. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ a b Drozdov 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Clapham, John Harold; Power, Eileen Edna (1941). The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: From the Decline of the Roman Empire. CUP Archive. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-08710-0.

- ^ Drozdov 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The papacy and the Levant: 1204-1571. 1 The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9. OCLC 165383496.

- ^ Drozdov 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1968). Discovery of the elements. Vol. 1 (7 ed.). Journal of chemical education. p. 187. ISBN 9780608300177.

- ^ a b Richards 1896, p. 2.

- ^ Richards 1896, p. 3.

- ^ Örsted, H. C. (1825). Oversigt over det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhanlingar og dets Medlemmerz Arbeider, fra 31 Mai 1824 til 31 Mai 1825 [Overview of the Royal Danish Science Society’s Proceedings and the Work of its Members, from 31 May 1824 to 31 May 1825] (in Danish). pp. 15–16. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters (1827). Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs philosophiske og historiske afhandlinger [The philosophical and historical dissertations of the Royal Danish Science Society] (in Danish). Popp. pp. xxv–xxvi. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ a b Wöhler, Friedrich (1827). «Ueber das Aluminium». Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2. 11 (9): 146–161. Bibcode:1828AnP….87..146W. doi:10.1002/andp.18270870912. S2CID 122170259. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Drozdov 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Fontani, Marco; Costa, Mariagrazia; Orna, Mary Virginia (2014). The Lost Elements: The Periodic Table’s Shadow Side. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-938334-4.