Номера на футболках игроков являются одной из самых обсуждаемых тем для болельщиков. Ярые поклонники выдвигают одно предположение за другим, почему их любимый футболист выбрал именно эти цифры, а новички пытаются вникнуть в сам принцип назначения номеров. Попробуем приоткрыть завесу тайны, однако многие секреты, к сожалению, нам познать так и не суждено, почему − узнаете далее.

Правила присвоения номеров футбольным игрокам

Изначально их было всего 11 — по количеству футболистов, и каждый из них означал определённую позицию, занимаемую игроком на поле. Например:

- 1 − вратарь;

- 5 − центральный полузащитник;

- 9 − центральный нападающий;

- 12 − запасной игрок.

Соответственно, при изменении позиции номер менялся. Однако позже от такой системы отказались, и в настоящее время игроки сами определяют для себя номера. И выбор сейчас гораздо шире − от 1 до 99.

Однако не все из них можно использовать. Многие клубы закрепляют определённый номер в честь какого-либо футболиста: либо как признание его заслуг, либо посмертно, как дань уважения памяти.

Справка! Легендарный игрок английского клуба «Челси» Джанфранко Дзола играл под номером 25, а за Миклошем Фехером, венгерским футболистом клуба «Бенфика», погибшим в 24 года прямо на поле от болезни сердца, закрепили номер 29.

Также существуют номера, не вышедшие из обращения, но обладающие определённым смыслом. Например, 10, под которым играл Пеле, присваивают лучшим футболистам команды. Клубы «ЦСКА», «Крылья Советов» и многие другие не используют номер 12, «подарив» его болельщикам, как «двенадцатым игрокам».

Суеверия, связанные с номерами на футболках

Вера в приметы не чужда и футболистам. Многие из них верят в то, что цифра дня их рождения принесёт им успех в карьере. Этого суеверия, например, придерживаются В. А. Шевчук (13 − 13.05.1979) и Р. П. Ротань (29 − 29.10.1981).

Однако большинство футболистов предпочитает держать значение выбранного ими числа в строжайшей тайне, что и является предметом многочисленных дискуссий болельщиков. Это тоже часть суеверия − многие считают, что раскрытие этого секрета может принести несчастье.

Другие верят в нумерологию и магическое значение цифр, а также всех их производных, включая результаты сложения, вычитания, умножения и деления.

Справка! Когда номера назначались в соответствии с позициями, запасные игроки, выходившие за двенадцатым номером, опасались брать тринадцатый и выходили под четырнадцатым.

Одной из самых известных теорий является так называемое Число судьбы, выведенное ещё Пифагором. Рассчитать его просто: достаточно сложить между собой все цифры даты рождения (за исключением 11 и 22, которые в таком виде и остаются, без сложения 1+1 и 2+2). Поклонники нападающего «Шахтёра» Александра Гладкого предполагают, что он взял номер 21 (2+1=3) именно по такому принципу, поскольку при сложении цифр даты его рождения как раз получается 3.

Также многие выбирают ту или иную цифру не для абстрактного «успеха» или «удачи», а для приобретения необходимых навыков, связанных со значением этого числа: воли, усердия, нестандартного мышления и т. д.

Оцените

(+3 баллов, 3 оценок)

![]() Загрузка…

Загрузка…

В кибер-футболе игроки не нуждаются в игровом номере, ведь каждый из них является единственным спортсменом, представляющим ту или иную команду на турнирах по FIFA или PES. В реальном большом футболе в составе обычно находится более 25 человек, каждый из них представляет цвета своего клуба, поэтому все игроки обладают отдельным игровым номером.

Правило присвоения футбольных номеров

Впервые с номерами на футболках сыграли игроки «Челси» и «Арсенала» в 1928 году, а уже в 40-ых годах нумерация игроков произошла и в СССР. Первоначально принцип распределения номеров был прост: номер 1 – голкипер, номера 2-8 занимались защитниками и полузащитниками, цифры 9-11 были при нападающих, а с цифры 12 нумеровались майки запасных игроков. То есть, даже когда игроки менялись позициями, менялись и их номера. Также, стоит отметить, что когда игрок стартового состава выбывал, заменяющий его игрок заимствовал его номер. В наше время расклад дел с игровыми номерами изменился, теперь можно выбрать номер от 1 до 99, но бывали и исключения, когда игрок выходил под номером (100, 0, 01 и т.п.). Таким образом, игрок сам выбирает понравившийся номер, если такой свободен и выступает за клуб именно под этой цифрой, не меняя ее при замене, или той же смене позиции.

Интересный факт! Саморано, игрок «Интера», играл под 9-м номером, который взял в память о погибшем отце, но когда его попросили отдать номер Роналдо, он сказал, что не может сменить номер и попросил договориться с федерацией футбола о том, чтобы ему разрешили играть под номером 1+8, переговоры прошли успешно.

Самые популярные номера в футболе

В футболе есть определенная категория наиболее популярных или даже престижных номеров. В состав легендарных цифр входят номера от 7 до 10 и, разумеется, первый номер.

Под 7-м номером играло и играет до сих пор множество именитых игроков. Лет 15 назад под данным игровым номером играло сразу несколько легенд. Луиш Фигу — играл под 7 номером в «Барселоне» и «Интере», многократный обладатель звания футболист года в Испании и Португалии, а также победитель в голосовании «Золотой Мяч» 2000 года. Дэвид Бэкхем также играл под 7 номером, он известен своими многочисленными трофеями, а также званиями спортсмен года и серебряными мячами. Ну и Криштиану Роналду, разумеется, футбольная легенда 21 века, обладатель кучи трофеев и многократный победитель в номинации «Игрок года», однозначная легендарная семерка нашего времени.

Далее, номер 8, также известный громкими именами. От Фрэнка Лэмпарда и Стивена Джеррарда до не менее легендарных чемпионов «Барселоны» – Андреса Иньесты и Христо Стоичкова,. Эти имена навечно оставили свой след в истории футбола, а игровой номер 8 всегда будет ассоциироваться с ними.

Множество известных имен выступали и под девятым игровым номером. Тут список имен можно перечислять очень долго: уругвайский «зубастик» — Суарез, оригинальный бразильский «зубастик» — Роналдо, испанский селебрити «Ливерпуля», «Атлетико» и «Челси» — Фернандо Торрес. Также, девятка стала легендарной и благодаря русским именам – например, Эдуарду Стрельцову.

10-ый номер, наверное, ассоциируется с наибольшим количеством легендарных игроков. Снейдер, Руни, Оуэн, Фабрегас — популярные футболисты, игравшие под 10 номером. Итальянские легенды: дель Пьеро, Тотти, Баджо, а также бразильские золотые десятки — Пеле и Роналдиньо. Настоящие легенды 20 века, играющие под десятым номером: Зидан, Марадона, Пушкаш, Платини. И куда без шестикратного обладателя «Золотого мяча» и «Золотой бутсы», великого «G.O.A.T», одной из легенд футбола XXI века, Лионеля Месси.

И в заключении, первый номер, преимущественно принадлежащий вратарям. Джанлуиджи Буффон, Оливер Кан и, конечно же, известный и великий советский вратарь, получивший «Золотой мяч» — Лев Яшин. Эти голкиперы навсегда оставили свой след в истории футбола.

За кем закрепляют номера в футболе

Вообще, в футболе цифры закрепляются в момент, когда футболист играет свой первый матч, тогда, собственно, его игровой номер вместе с данными заносятся в протокол. Кстати, позднее появилась традиция или даже правило о закреплении игрового номера, если игрок очень выдающийся, игрок трагически погиб или как дань уважения игроку, получившему травму, повлекшую за собой уход из футбола.

Обратите внимание! Наиболее популярные закрепленные номера: Мальдини («Милан») — номер 3, Дзанетти («Интер») — номер 4, Кройф («Аякс») — номер 14.

Лучшие букмекеры для ставок на футбол

Этот пост написан пользователем Sports.ru, начать писать может каждый болельщик (сделать это можно здесь).

Почему номера на футболках игроков фубольных клубов различаются от страны к стране?

Номера на футболках футбольных команд впервые были использованы в европейском футболе

25 августа 1928 года в матчах между Шеффилд Уэнсдей и Арсеналом, а также Челси и Суонси. Нномера на футболках игроков также были представлены двумя малоизвестными австралийскими клубами, прежде чем они пробились в Аргентину и США, а затем появились на большой сцене в Англии в финале Кубка Англии 1933 года, где Эвертон носил футболки с номерами с 1 по 11, а Ман Сити — с 12 по 22. Эта эволюция положила начало соглашению о нумерации игроков, согласно определенной методике: в зависимости от месторасположения игрока на поле.

В то время как вратарь был номинально, чаще всего первым номером, по причине того что он был первым названным игроком в командном листе, четыре вратаря, участвовавших в этих играх, не имели номеров на своих футболках; Вратари носили футболки разного цвета с тех пор, как эта практика была введена в Шотландии в 1909 году, а в 1921 году она стала обязательной во всем мире.

По словам Майкла Миллара, номера на футболках использовались в Австралии с 1911 года, в то время как в 1923 году аргентинская команда принимала шотландскую, в этом матче обе команды носили футболки с номерами от 1 до 11, а в Соединенных Штатах игроки команды Веспер Бьюик носили номера на футболках, участвуя в Национальном кубке вызова в 1924 году, хотя их противники, Стрелки Фолл-Ривер, этого не делали.

Номера — соответствие определенной позиции

Соглашение о номерах утратило актуальность после середины 90-х годов, когда национальные лиги начали принимать собственные системы нумерации игроков команд, а не просто присваивали стартовым игрокам порядковые номера от 1 до 11.

В Германии идут дальше. Опорных полузащитников там именуют «Sechser» (от Sechs = шесть). Центральных полузащитников называют «Achter» (от Acht = восемь), атакующих полузащитников — «Zehner» (от Zehn = десять). Кроме того, у некоторых номеров есть приятные моменты на некоторых позициях: Номер один — очевидно, вратарь; номер двенадцать запрещен к употреблению в большинстве немецких команд, потому что этот номер принадлежит болельщикам — двеннадцотому игроку на поле; номера девять и одинадцать почти всегда имеют нападающие; семерки по умолчанию вингеры; два, три, четыре почти всегда игроки защитной линии; номер пять либо защитник, либо глубоко расположенный на поле полузащитник, опорник с упором на оборонительную работу. И еще одна немецкая особенность, номер десять часто дают лучшему игроку.

В сингапурском футболе номер семнадцать является одним из самых узнаваемых, если не самым узнаваемым из-за того, что лучший футболист Сингапура Фанди Ахмад носил этот номер, играя за сборную.

В Англии, если рассматривать значение номеров в классической системе 4-4-2, где номер один это голкипер, правый защитник номер два, левый защитник номер три, центральные защитники номера пять и шесть соответственно, правый полузащитник / вингер номер семь, центральные полузащитники номера четыре и восемь, где, как правило, более оборонительный центральный полузащитник носит номер четыре, а атакующий номер восемь, левый полузащитник / вингер номер одинадцать, и нападающие номера девять и десять, где номер десять обычно играет немного глубже, между линиями, выступая как бы связующим звеном.

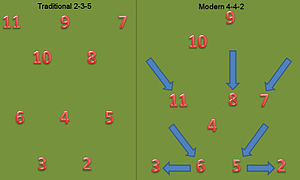

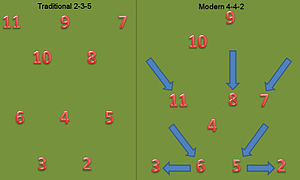

Соглашения о нумерации игроков в значительной степени основаны на тактическом переходе от доминирующей когда то структуры 2-3-5 к другим системам. Таким образом, номера игроков могут косвенно рассказать историю о том, как такие страны, как Англия и Бразилия, по-разному перешли к четверке защитников, потому что полузащитники в схеме 2-3-5 выполняли разные функции во время перехода и, следовательно, игроки имели разные номера в каждой стране. Из-за этого, наибольшие отличия в номерах встречаются у защитников и центральных полузащитников.

Изменения начались, когда Герберт Чепмен начал вводить систему «W-M», в ответ на изменение правила об офсайде, которому, по мнению Чепмена, следует противодействовать опуская центрального полузащитника в пространство между крайними защитниками. Это означало, что номер 5 располагался между номерами 2 и 3 в классическом понимании системы «W-M», поэтому в большинстве стран, где четверка защитников произошла из системы «W-M», правый центральный защитник имеет номер 5. Отчасти это также связано с тем, что, Футбольная ассоциация сделала правило о номерах общеобязательным, случилось это в 1939 году, также они настаивали на использовании нумерации, основанной на структуре 2-3-5, так что игрок центральной половины поля должен был иметь 5 номер, несмотря на то, что он фактически исполнял роль защитника, в системе «W-M».

Защитники Сборной Венгрии, в 50-х годах, на которые пришлась великолепная победа на Сборной Англии со счетом 6-3, имели номера со 2 по 4, в матчах, когда они играли по системе «M-M», с перевернутой «W», потому что венгерский игрок Нандор Хиндегкути исполнял роль замыкающего, оттянутого нападающего, играющего в центре поля. Венгрию тренировал Густав Себеш, но в основном она следовала нововведениям и идеям влиятельного Мартона Букови. Нумерация венгерских игроков вызвала некоторые затруднения у англичан, потому что они привыкли к предыдущей, простой цифровой маркировке, на основании которой они следовали простым правилам: «семерка принимает тройку, пятерка девятку», и так далее.

Нечетная нумерация игроков Венгрии и изменение системы привели к тому, что Англия пыталась приспособиться к этому. В английском футболе настолько привыкли к обычной цифровой маркировке игроков, что, как отмечает Джонатан Уилсон, приводило к следующим казусам: «тренер «Донкастер Роверс» Питер Доэрти добился успеха в пятидесятых благодаря уловке, заключавшейся в том, что он время от времени заставлял своих игроков меняться футболками, тем самым приводя в замешательство игроков противника».

В Аргентине смена концепции игры в защите фактически привела к тому, что правый полузащитник переместился в зону правого защитника, а фланговый защитник в системе 2-3-5 переместился на позицию правого полузащитника; вот почему, например, легендарный аргентинский правый защитник Хавьер Дзанетти предпочитал номер четыре, а игроки правой половины поля сдвинулись назад, центральный защитник имел второй номер, поэтому номера аргентинской четверки защитников фактически читались как 4-2-6-3. (Как описал Джонатан Уилсон в своей книге «Инвертированная Пирамида»).

Но до того, как игроки смогли выбирать определенный номера и сохранять их за собой, некоторые альтернативные причины распределения номеров привели к довольно странным результатам, например, к алфавитному порядку. Аргентина придерживалась этой политики на чемпионатах мира 1974, 78, 82 и 86 годов, как и Нидерланды на некоторых из этих турниров. Распределение номеров на футболках в алфавитном порядке привело к некоторым сумасшедшим результатам, например, голландский вратарь Ян Йонгблед присвоил номер 8, а аргентинский полузащитник Осси Ардилес надел футболку с номером 1. Однако в обеих командах большие звезды сохранили свои любимые номера. Диего Марадона носил номер 10, а Йохан Кройф — номер 14. Он, кстати, выбрал номер 14, поступив благородно, уступив товарищу по команде в Аяксе номер семь, и четырнадцатый номер был первым, который Кройф вытащил из корзины.

Смена концепции, схемы игры, движений игроков, а также отсутствие постоянных ролей стали триггером сдвига идеи о номерах игроков, основывающейся на зависимости от их расположения на поле.

В Бразилии все было по-другому. Номера бразильской четверки защитников читались как 2-4-3-6, потому что вместо правой половины, опускающейся назад, как у Аргентины, у них это была левая. Переход Уругвая к четверке защитников, который произошел непосредственно из структуры 2-3-5, привел к тому, что крайние фланговые игроки двигались назад и в центр, что имеет смысл, если это движение происходило из схемы 2-3-5. Это означает, что номера уругвайских защитников читались как 4-2-3-6.

Переход полузащитников в защитную линию оказал влияние и на нумерацию других игроков. В Англии опорный полузащитник с защитными функциями, имел номер четыре, потому что два центральных защитника имели номера пять и шесть, соответственно; в Европе этот же игрок играл под шестым номером. В Южной Америке подобные игроки играли под пятым номером, они выполняли функции «разрушителей» атак соперника, но также и исполняли задачи глубинных плеймейкеров, которые тоже могли разрушать, например, такие игроки как Фернандо Редондо или Лукас Биглия.

Также стоит отметить, что для атакующих позиций номера на футболках приобрели особый резонанс, который не столько связан с позицией, сколько связан с конкретной функцией или даже определенным символизмом. Так номер десять — ассоциировался с такими игроками, как Пеле, Марадона, Рикельме, Баджо, и символизирует атакующие способности, чутье, креативность. Одиннадцатый номер — хитрые, быстрые вингеры, как и семерки, хотя они также могут быть атакующими полузащитниками или крайними нападающими. Номер семь, конечно же, знаменует собой начало атакующих номеров, а футболка с этим номером стала ассоциироваться не более чем с определенными игроками — Бестом, Кантоной, Бекхэмом, — чем с идеалом ролевой позиции. Десятки в бразильском футболе иногда играют роль прогрессивного полузащитника при схеме 4-3-3; в таком случае этот номер несёт в себе определенные ожидания из-за конкретных качеств игроков, таких как Зико и Пеле, но уже с другой ролью, и игрок с седьмым номером может быть правым центральным полузащитником, как это было в схеме 3-5-2 Карлоса Билардо. Ношение культового номера заставляет игроков чувствовать себя частью прославленного клуба, связанного с великими людьми. Иногда давление культового числа может оказаться слишком тяжелым для игрока, так Антонио Валенсия фактически переключился на 25 номер после того, как не смог найти свою игру в своей новой футболке с номером 7.

Но если и есть различия в нумерации атакующих позиций, то они менее выражены, чем оборонительные. В основном это связано с тем, что позиции атакующих игроков подверглись меньшей трансформации в момент перехода игры по системе 2-3-5 на другие классические схемы, например 4-4-2, которая была доминирующей до того, как была введена нумерация команд.

НОМЕРА КАК БРЕНД

Теперь игроки начали объединяться и формировать свой собственный бренд вокруг своих номеров, что стало еще более важным в эпоху социальных сетей. Криштиану Роналду носил 28-й номер в Спортинге и первоначально 17-й в Португалии, но сэр Алекс Фергюсон вручил ему культовый номер 7 в Юнайтед. Это породило символ CR7, его прозвище и международный бренд, охватывающий отели, спортивные залы и даже нижнее белье. Это было прервано, когда он переехал в Мадрид в 2009 году, на тот момент у легенды клуба Рауля все еще была семерка, и он не собирался ее отдавать. Выглядит странно и по сей день. Ранее Рауль также заставил Дэвида Бекхэма переосмыслить свой выбор номера.

Однако для некоторых игроков номер это число, которое заставляет их чувствовать себя ценными. Им просто нужен номер, который предает им определенный статус. У игроков есть эго, и иногда они делают странный выбор, чтобы чувствовать себя более важными. Если стоит выбор между большим и маленьким числом, обычно футболисты выбирают последнее. Глен Джонсон выбрал восьмой номер, когда перешел в Сток, хотя занимал позицию защитника.

Самый абсурдный пример — это, наверное, Уильям Галлас, играющий в Арсенале под 10-м номером. Его просьба иметь важный номер после подписания контракта в 2006 году была разумной. Хотя номер 10 раньше носил Деннис Бергкамп, Галлас отказался от третьего номера3, поскольку он хотел дать всем понять, что он центральный защитник, а не левый защитник, а Арсен Венгер не хотел обременять форварда лишними сравнениями с Бергкампом, но это произошло.

В конце концов, числа перестали иметь большое значение после того, как появилась нумерация по группам игроков, но идея тактических сдвигов, придающих определенным номерам функцию, сохранилась, и игроки действительно выбирают номера на этой основе. Влияние изменений после перехода с 2-3-5 сохраняется и по сей день.

Закончим несколькими странными примерами из США. Швейцарский игрок Ален Сюттер носил футболку с номером 66 в «Даллас Берне» в связи с шоссе 66. Единственная проблема, маршрут номер 66 не проходит через Даллас. В клубе Такома Дифайенс все игроки носят очень большие номера без видимой причины. Самый маленький номер в команде — это номер 18, а самый маленький постоянный номер игрока — это номер 31, который носит вратарь. У большей части команды номера выше 50.

Так что, будь то история, суеверие, статус или глупость, номера на футболках выбираются по целому ряду причин. От 0 до 121, по-видимому, некоторые варианты более логичны, чем другие.

СПАСИБО ЗА ВНИМАНИЕ И ЛЮБИТЕ НАСЛАЖДАЙТЕСЬ ФУТБОЛОМ

Карьера каждого футболиста начинается с присвоения ему номера, который значится у него на спине. Под этим номером его фамилию заносят в протокол матча и именно благодаря этому номеру начинающих игроков запоминают болельщики.

ФОТО Анны МЕЙЕР/fc-zenit.ru

В футбол в том виде, каким мы его знаем, играют где-то с середины девятнадцатого века, однако номера на футболках появились намного позже, но тоже, естественно, в Англии, где первопроходцами стали «Челси» и «Арсенал». У нас цифры на футболках появились еще позже, в 1946 году, и благодаря все тем же англичанам. Во время знаменитого послевоенного турне московского «Динамо» по Великобритании наши футболисты оценили находчивость англичан и переняли этот опыт.

В стартовом составе были футболисты с номерами от первого до одиннадцатого (по количеству игроков в команде), и распределялись они в зависимости от занимаемой позиции на поле. 1-й — всегда вратарь, со 2-го по 5-й — защитники и так далее по восходящей. Причем никаких 12-х, 13-х и далее — они появились еще позже, когда в футболе разрешили делать замены. Так что футболисты долгое время не имели постоянных номеров — сегодня ты играешь, а завтра серьезно травмирован или просто приболел, и в твоей майке и под твоим номером тренер выпускает уже кого-то другого.

Исключения случались только на чемпионатах мира и Европы, где за всеми участниками на время турнира закреплялись постоянные номера — от 1-го до 22-го по количеству заявленных футболистов. Процесс распределения номеров порой оборачивался конфликтами среди футболистов. Мало того что никто не хотел футболку с несчастливой цифрой 13, так еще и в сборной часто сталкивались игроки, привыкшие играть в своих клубах под определенным номером, и никто не хотел уступать привычную «пятерку» или «девятку». В сборной Аргентины на ЧМ-1982 вопрос встал настолько остро, что главный тренер Луис Менотти распределил номера в соответствии с алфавитным порядком. В итоге, к удивлению всего футбольного мира, полузащитник Освальдо Ардилес играл в поле под «единицей», в то время как Убальдо Филол защищал ворота с «семеркой» на спине. Правда, для одного из футболистов пришлось сделать исключение — Диего Марадона мог появиться на публике только под номером 10.

«Десятка» считается среди футболистов самым популярным и престижным номером. Во многом благодаря все тому же Марадоне, но сам он тоже неспроста настаивал на этом сочетании цифр — под «десяткой» выступал в свое время сам король футбола на все времена Пеле. Правда, получил бразилец номер, под которым его узнал весь мир, как рассказывают, по нелепой случайности: дома отправлявшимся на ЧМ-1958 в Швецию игрокам номера никто не присвоил, а уже на месте некий чиновник ФИФА, оформляя заявку, что называется, от фонаря расставил номера в списке, и безвестный тогда еще Пеле на всю оставшуюся великую футбольную жизнь получил 10-й номер. До сих пор под ним выступают, как правило, либо ударный форвард, либо плеймейкер.

В самом первом золотом составе «Зенита» образца 1984 года «десятка» была закреплена за Вячеславом Мельниковым. «Я не помню, чтобы за ней или за каким-то другим номером шла борьба. Все естественным образом получалось — на какой позиции играешь, такую футболку тебе и дали, — вспоминает Мельников. — Мне досталась «десятка», Давыдову — «двойка», Ларионову — «шестерка» и так далее. Когда играл в основном составе, то выходил под своим номером, хотя официально он никак за мной закреплен не был. И никаких ассоциаций с Пеле или Марадоной никогда не было. Мне кажется, только в последнее время 10-й номер стал брендовым». Интересно, что, когда Мельников уже был главным тренером «Зенита», в его команде под «десяткой» играл Владимир Кулик, лучший бомбардир петербургской команды начала 1990-х. С этим номером он ушел и в ЦСКА к Павлу Садырину, а в «Зените» цифра 10 теперь ассоциируется исключительно с Андреем Аршавиным.

Под этим номером он неизменно играл с самых детских лет, а когда пришло время дебютировать в главной команде, заветная футболка оказалась занята, причем самим капитаном команды Андреем Кобелевым. Как раз тогда, в начале нулевых, в футбол повсеместно стала входить практика постоянно закрепленных за игроками номеров, как на чемпионатах мира. Только если на мундиалях все ограничивается количеством внесенных в заявку футболистов (22), то в чемпионате России это может быть любой двузначный номер. Причем инициаторами стали не сами футболисты, а те, кто готовил им форму. На игровых майках к тому времени уже появились фамилии игроков, а номера с 1-го по 11-й часто менялись, что вызывало определенные технические сложности. Если тренеры определялись с основным составом перед самой игрой, времени на то, чтобы налепить правильные номера, оставалось крайне мало! За новшество двумя руками выступили и телевизионщики — комментаторы смогли легко определять футболистов не только по характерной прическе, вечно спущенным гетрам или майке навыпуск.

Аршавин начал в «Зените» под 23-м номером, затем был 15-й, и, даже когда Кобелев вернулся в Москву, заветная «десятка» ему досталась не сразу — она ушла, исходя из традиционного питерского гостеприимства, Владимиру Мудриничу, первому легионеру в составе «Зенита». На счастье Аршавина, серб задержался в Петербурге ненадолго, и уже в 2003 году будущему зенитовскому капитану досталось то, к чему он привык с детства. В «Арсенале» Андрею снова пришлось надевать майку с номером 23 (под 10-м при нем за «канониров» играли такие авторитетные ребята, как француз Вилльям Галлас и голландец Робин ван Перси), а когда он вернулся в Петербург, его «десятка» была уже у Мигеля Данни. После португальца в этой футболке по одному сезону провели Жулиано и Клаудио Маркизио, а стоило итальянцу разорвать контракт с «Зенитом» этим летом, как Эмилиано Ригони поспешил сдать свой 24-й номер и «приватизировать» 10-й — под ним он заявлен в начавшемся чемпионате. Вот только пока аргентинец не выходит на поле, и вообще дефицитная футболка вполне может освободиться до закрытия трансферного окна. Не исключено, что ее предложат потенциальному новичку Малкому, тем более что 7-й и 14-й номера, под которыми он играл за «Бордо» и «Барселону», в Петербурге на данный момент заняты, соответственно, Сердаром Азмуном и Далером Кузяевым. Среди претендентов может оказаться теоретически и Артем Дзюба, игравший под десятым за юношескую сборную России, «Спартак» и «Ростов». «Мне бы хотелось взять 22-й или 10-й, это мои любимые номера», — говорил перед дебютом в «Зените» Артем, который и на домашнем ЧМ-2018 совершал свои подвиги в футболке с числом 22.

Под этим номером выступал в свое время за «Зенит» и Александр Анюков, пока не завершил карьеру Владислав Радимов и освободилась «двойка». Был период, когда защитник вернулся к 22-му, якобы на фарт — футболиста как раз стали преследовать травмы. Под этим номером он и возобновил этим летом свою активную карьеру в «Крыльях Советов». А самый первый сезон в «Зените» в 2004 году совсем молодой Анюков проводил, между прочим, под номером 44, который позже достался Анатолию Тимощуку. И тоже не от хорошей жизни — в «Шахтере» и сборной Украины его знали как «четверку», а в «Зените» она была занята Ивицей Крижанацем. Тимощук в итоге удвоил свой любимый номер и остался ему верен, даже играя в Германии за «Баварию». А в «Зените» 44-й по-прежнему остается украинским, под ним теперь выступает Ярослав Ракицкий. Но не потому, что он достался ему по наследству от соотечественника, по инициативе которого, кстати, оказался в «Зените», — 44-м Ракицкий был и в донецком «Шахтере» с первого дня в этой команде, и вот тогда он действительно подражал Тимощуку.

Как правило, футболист сам предлагает какую-то цифру, под которой он уже играл прежде или которая ему просто нравится. Это может быть дата его рождения, цифра из телефона любимой девушки или даже телефонный код родного города, как у игравшего в «Зените» под 61-м номером турка Фатиха Текке. Ну а если заветная цифра оказывается занятой, начинается мучительный выбор. Первые одиннадцать номеров по-прежнему в почете у игроков, они достаются обычно самым именитым, в то время как молодежи достаются более крупные цифры. Но и они, бывает, остаются им верны. Игорь Денисов и Владимир Быстров получили свои футболки с номерами 27 и 34, когда только попали в дубль «Зенита», и играли под ними даже во всех других командах, хотя с их-то авторитетом спокойно могли забрать себе любой другой номер.

Случается, что футболисты договариваются между собой и кто-то жертвует своим любимым номером ради партнера. Но получается не всегда и приходится идти на различного рода ухищрения. Дальше всех в этом плане пошел чилиец Иван Саморано, игравший в середине 1990-х за «Интер» под «девяткой», пока в эту команду не перешел из «Барселоны» знаменитый Роналдо — бразилец поставил одним из условий передачу ему футболки с номером 9. Саморано долгое время протестовал, но в конце концов взял номер 18 с малюсеньким знаком «плюс» между цифрами, то есть на спине у него значилось «1+8», пока все это не разглядели чиновники из федерации.

Номер 18 любимый у Юрия Жиркова, но в «Зените» он ему достался только после ухода Константина Зырянова, и первые два сезона в Петербурге бывший московский армеец выступал под 81-м номером. Похожим образом поступил этим летом и один из последних новичков «сине-бело-голубых» Алексей Сутормин (на снимке слева). «Раньше я выступал под 19-м номером, но в «Зените» под ним играет Игорь Смольников. И я решил, что нужно сделать наоборот — поменять цифры местами», — рассказывает 91-й номер петербургской команды. А еще один зенитовский новобранец Дуглас Сантос (на снимке справа) вынужден был по приезде в Петербург заняться арифметикой. Последние три сезона в «Гамбурге», а до этого на родине в «Атлетико Минейро» он был «шестеркой», но так как под ней в «Зените» играет капитан Бранислав Иванович, бразилец поделил любое число пополам и играет под 3-м номером.

Материал опубликован в газете «Санкт-Петербургские ведомости» № 141 (6494) от 02.08.2019 под заголовком «Такие вот номера!».

Материалы рубрики

Комментарии

Номер на майке футболиста – это не простая цифра. Она имеет более глубокий смысл. Как и зачем игрокам присваиваются цифры, мы сегодня Вам и расскажем.

Из истории футбола

Футбол – довольно древняя игра. Играли в него еще в Древней Спарте. Мячом служил кожаный мешок, набитый перьями. Мяч кидали руками, пинали ногами, подкидывали. В каждой стране были свои особые правила игры в футбол. Да и назывался он по-разному (Чжу-кэ, Эпискирос, Харпастум, Кальчо и так далее). Неизменным оставался лишь смысл игры – не дать сопернику заполучить мяч. С веками футбол всех стран начал приходить к общему знаменателю и выглядеть одинаково.

Современный облик футбол окончательно принял в середине 19 века, и с тех пор он почти не менялся.

Цифры на майках первыми опробовали англичане в 1928 году, а именно игроки «Арсенала» и «Челси». В 1946 году эстафету переняли и советские футболисты. С тех пор числовое обозначение игроков прочно вошло в историю мирового футбола.

Зачем нужны цифры

Наверно, мы Вас не удивим, если скажем, что изначально нумеровали игроков с целью удобства. Принцип был следующим:

- Первый номер получал вратарь.

- Со 2 по 5 – защитники. 5 номер – у центрального полузащитника.

- Под 9 номером играл центральный нападающий.

- Скамья запасных нумеровалась от 12.

Если из основного состава выбывал игрок (например, по причине травмы на поле) его заменяли игроком со скамьи запасных. В таком случае запасной получал номер основного.

Когда в основной команде игроки менялись местами, то их номера менялись также. Но такое положение вещей осталось в прошлом веке.

Сейчас цифра футболиста – это его личный код, который имеет большое значение не только для него лично, но и для ФИФА в целом.

Как только новый игрок приступает к своему первому матчу, за ним закрепляют номер, который наряду с ФИО заносятся в протокол.

На сегодняшний день диапазон цифр не ограничивается 12. Выбирать можно от 1 до 99. Код может быть один на всю жизнь, а может меняться несколько раз в течение карьеры

В качестве своего талисмана удачи игроки берут свою дату рождения или другую значимую дату из своей жизни, тайну которой они не раскрывают.

Среди футболистов особым уважением считается, если номер вывели из списка. Это означает, что игрок достиг максимума в своей карьере либо погиб. В последнем печальном варианте номер выводят с целью увековечивания памяти знаменитости.

А Вы обозначаете любимого игрока по номеру или, все-таки, по фамилии?

Squad numbers are used in association football to identify and distinguish players that are on the field. Numbers very soon became a way to also indicate position, with starting players being assigned numbers 1–11, although in the modern game they are often influenced by the players’ favourite numbers and other less technical reasons, as well as using «surrogates» for a number that is already in use. However, numbers 1–11 are often still worn by players of the previously associated position.[1]

As national leagues adopted squad numbers and game tactics evolved over the decades, numbering systems evolved separately in each football scene, and so different countries have different conventions. Still, there are some numbers that are universally agreed upon being used for a particular position, because they are quintessentially associated with that role.[1]

For instance, «1» is frequently used by the starting goalkeeper, as the goalkeeper is the first player in a line-up.[1] It is also the only position on the field that is required to be occupied. «10» is one of the most emblematic squad numbers in football,[2] due to the sheer number of football legends that used the number 10 shirt; playmakers, second strikers, centre-forwards and attacking midfielders usually wear this number.[1] «7» is often associated with effective and profitable wingers or second strikers.[1] «9» is usually worn by strikers, who hold the most advanced offensive positions on the pitch, and are often the highest scorers in the team.[1]

History[edit]

First use of numbers[edit]

First use of numbers in South America: Third Lanark and Argentine «Zona Norte» combined entering to the pitch with numbered jerseys, 10 June 1923

Arsenal FC wearing numbered shirts in a friendly v FC Vienna in 1933. Numbered shirts had first appeared in England in 1928 when Arsenal played Sheffield Wednesday. Their use would not be ruled mandatory until 1939

The first record of numbered jerseys in football date back to 1911, with Australian teams Sydney Leichardt and HMS Powerful being the first to use squad numbers on their backs.[3] One year later, numbering in football would be ruled as mandatory in New South Wales.[4]

The next recorded use was on 23 March 1914, when the English Wanderers, a team of amateur players from Football League clubs, played Corinthians at Stamford Bridge, London. This was Corinthians first match after their FA ban for joining the Amateur Football Association was rescinded. Wanderers won 4–2.[5]

In South America, Argentina was the first country with numbered shirts. It was during the Scottish team Third Lanark tour to South America of 1923, they played a friendly match v a local combined team («Zona Norte») on 10 June. Both squads were numbered from 1–11.[2]

30 March 1924, saw the first football match in the United States with squad numbers, when the Fall River Marksmen played St. Louis Vesper Buick during the 1923–24 National Challenge Cup, although only the local team wore numbered shirts.[6][7]

The next recorded use in association football in Europe was on 25 August 1928 when The Wednesday played Arsenal[8] and Chelsea hosted Swansea Town at Stamford Bridge. Numbers were assigned by field location:

- Goalkeeper

- Right full back (right side centre back)

- Left full back (left side centre back)

- Right half back (right side defensive midfield)

- Centre half back (centre defensive midfield)

- Left half back (left side defensive midfield)

- Outside right (right winger)

- Inside right (attacking midfield)

- Centre forward

- Inside left (attacking midfield)

- Outside left (left winger)

In the first game at Stamford Bridge, only the outfield players wore numbers (2–11). The Daily Express (p. 13, 27 August 1928) reported, «The 35,000 spectators were able to give credit for each bit of good work to the correct individual, because the team were numbered, and the large figures in black on white squares enabled each man to be identified without trouble.» The Daily Mirror («Numbered Jerseys A Success», p. 29, 27 August 1928) also covered the match: «I fancy the scheme has come to stay. All that was required was a lead and London has supplied it.» When Chelsea toured Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil at the end of the season in the summer of 1929, they also wore numbered shirts, earning the nickname «Los Numerados» («the numbered») from locals.

A similar numbering criteria was used in the 1933 FA Cup Final between Everton and Manchester City.[9] Nevertheless, it was not until the 1939–40 season when The Football League ruled that squads had to wear numbers for each player.[9][6]

Early evolutions of formations involved moving specific positions; for example, moving the centre half back to become a defender rather than a half back. Their numbers went with them, hence central defenders wearing number 5, and remnants of the system remain. For example, in friendly and championship qualifying matches England, when playing the 4–4–2 formation, generally number their players (using the standard right to left system of listing football teams) four defenders – 2, 5, 6, 3; four midfielders – 7, 4, 8, 11; two forwards – 10, 9. This system of numbering can also be adapted to a midfield diamond with the holding midfielder wearing 4 and the attacking central midfielder wearing 8. Similarly the Swedish national team number their players: four defenders – 2, 3, 4, 5; four midfielders – 7, 6, 8, 9; two forwards – 10, 11.

The 1950 FIFA World Cup was the first FIFA competition to see squad numbers for each players,[10] but persistent numbers would not be issued until the 1954 World Cup, where each man in a country’s 22-man squad wore a specific number from 1 to 22 for the duration of the tournament.

Evolution[edit]

In 1993, The Football Association (The FA) switched to persistent squad numbers, abandoning the mandatory use of 1–11 for the starting line-up. The first league event to feature this was the 1993 Football League Cup Final between Arsenal and Sheffield Wednesday, and it became standard in the FA Premier League the following season, along with names printed above the numbers.[6] Charlton Athletic were among the ten Football League clubs who chose to adopt squad numbers for the 1993–94 season (with squad numbers assigned to players in alphabetical order according to their surname), before reverting to 1–11 shirt numbering a year later.[11]

Squad numbers became optional in the three divisions of The Football League at the same time, but only 10 out of 70 clubs used them. One of those clubs, Brighton & Hove Albion, issued 25 players with squad numbers but reverted to traditional 1–11 numbering halfway through the season.[12] In the Premier League, Arsenal temporarily reverted to the old system halfway through that same season, but reverted to the new numbering system for the following campaign. Most European top leagues adopted the system during the 1990s.[6] The Football League made squad numbers compulsory for the 1999–2000 season, and the Football Conference followed suit for the 2002–03 season.

The traditional 1–11 numbers have been worn on occasions by English clubs since their respective leagues introduced squad numbers. Premier League clubs often used the traditional squad numbering system when competing in domestic or European cups, often when their opponents still made use of the traditional squad numbering system. This included Manchester United’s Premier League clash with Manchester City at Old Trafford on 10 February 2008, when 1950s style kits were worn as part of the Munich air disaster’s 50th anniversary commemorations.

Players may now wear any number (as long as it is unique within their squad) between 1 and 99.

In continental Western Europe this can generally be seen:

1– Goalkeeper

2– Right Back

3– Left Back

4– Centre Back

5– Centre Back (or Sweeper, if used)

6– Central Defensive/Holding Midfielder

7– Right Attacking Midfielders/Wingers

8– Central/Box-to-Box Midfielder

9– Striker

10– Attacking Midfielder/Playmaker

11– Left Attacking Midfielders/Wingers

This changes from formation to formation, however the defensive number placement generally remain the same. The use of inverted wingers now sees traditional right wingers, the number 7’s, like Cristiano Ronaldo, on the left, and traditional left wingers, the number 11’s, like Gareth Bale, on the right.

Numbering by country[edit]

Argentina[edit]

Argentina developed its numeration system independently from the rest of the world. This was because until the 1960s, Argentine football developed more or less isolated from the evolution brought by English, Italian and Hungarian coaches, owing to technological limitations at the time in communications and travelling with Europe, lack of information as to keeping up with news, lack of awareness and/or interest in the latest innovations, and strong nationalism promoted by the Asociación del Fútbol Argentino (for example, back then Argentines playing in Europe were banned from playing in the Argentine national team).

The first formation used in Argentine football was the 2–3–5 and, until the ’60s, it was the sole formation employed by Argentine clubs and the Argentina national football team, with only very few exceptions like River Plate’s La Máquina from the ’40s that used 3–2–2–3. It was not until the mid 1960s in the national team, with Argentina winning the Taça das Nações (1964) using 3–2–5, and the late ’60s, for clubs, with Estudiantes winning the treble of the Copa Libertadores (1968, 1969, 1970) using 4–4–2, that Argentine football finally adopted modern formations on major scale, and caught up with its counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic.

While the original 2–3–5 formation used the same numbering system dictated by the English clubs in 1928, subsequent changes were developed independently.

The basic formation to understand the Argentine numeration system is the 4–3–3 formation, like the one used by the coach César Menotti that made Argentina win the 1978 World Cup, the squad numbers employed are:

- 1 Goalkeeper

- 4 Right Back[13]

- 2 First Centre Back / Sweeper

- 6 Second Centre Back / Stopper

- 3 Left Back[14]

- 8 Right Midfielder

- 5 Central Defensive Midfielder[15]

- 10 Left Midfielder

- 7 Right Winger

- 11 Left Winger

- 9 Striker

Brazil[edit]

In Brazil, the 4–2–4 formation was developed independently from Europe, thus leading to a different numbering – here shown in the 4–3–3 formation to stress that in Brazil, number ten is midfield:

- 1 Goleiro (Goalkeeper)

- 2 Lateral Direito (right wingback)

- 3 Beque Central (centre back)

- 4 Quarto Zagueiro (the «fourth defender», almost the same as a centre back)

- 6 Lateral Esquerdo (left wingback)

- 5 Volante («Rudder» or «mobile», the defensive midfielder)

- 8 Meia Direita (right midfielder)

- 10 Meia Esquerda (left midfielder, generally more offensive than the right one)

- 7 Ponta Direita (right winger)

- 9 Centro-Avante (centre-forward)

- 11 Ponta Esquerda (left winger)

When in 4–2–4, number 10 passes to the Ponta de Lança (striker), and 4–4–2 formations get this configuration: four defenders – 2 (right wingback), 4, 3, 6 (left wingback); four midfielders – 5 (defensive), 8 («second midfielder»), similar to a central midfielder), 7, 10 (attacking); two strikers – 9, 11

France[edit]

In France, players must be registered between numbers 1–30, with 1 and 16 reserved for goalkeepers and 33 left empty for extra signings. In case a fourth goalkeeper has to be registered, he wears number 40.[16]

Hungary[edit]

In Eastern Europe, the defence numbering is slightly different. The Hungarian national team under Gusztáv Sebes switched from a 2–3–5 formation to 3–2–5. So the defence numbers were 2 to 4 from right to left thus making the right back (2), centre back (3) and the left back (4). Since the concept of a flat back four the number (5) has become the other centre back.

Italy[edit]

In 1995, the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) also switched to persistent squad numbers for Serie A and Serie B (second division), abandoning the mandatory use of 1–11 for the starting lineup. After some years during which players had to wear a number between 1–24, now they can wear any number between 1–99 without restrictions. Notably, Chievo Verona had the goalkeeper Cristiano Lupatelli wearing number 10 from 2001 to 2003[17] and midfielder Jonathan de Guzman wearing number 1 in 2016.[18]

Spain[edit]

In the Spanish La Liga, players in the A-squad (maximum 25 players, including a maximum of three goalkeepers) must wear a number between 1–25. Goalkeepers must wear either 1, 13 or 25. When players from the reserve team are selected to play for the first team, they are given squad numbers between 26 and 50.

United Kingdom[edit]

Players are not generally allowed to change their number during a season, although a player may change number if they change clubs mid-season. Players may change squad numbers between seasons, this often happens when a player’s role in the first team increases or diminishes. Occasionally, when a player has two loan spells at the same club in a single season (or returns as a permanent signing after an earlier loan spell), an alternative squad number is needed if the original number assigned during the player’s first loan spell has been reassigned by the time the player returns.

A move from a high number to a low one may be an indication that the player is likely to be a regular starter for the coming season, particularly after at least one preceding season of increased first team opportunities. An example of this is Celtic’s Scott McDonald, who, after the departure of former number 7 Maciej Żurawski, was given the number, a move down from 27.[19] Another example is Steven Gerrard, who wore number 28 (which was his academy number) during his debut 1998–99 season, then switched to number 17 in 2000–01. In 2004–05, after Emile Heskey left Liverpool, Gerrard then changed his number again to 8. More recently, Tottenham Hotspur striker Harry Kane changed his number 37 shirt from the 2013–14 season to 18 for the 2014–15 season when he became one of the club’s first-choice strikers after Jermain Defoe was sold and the number 18 was vacated. Kane then switched to the number 10 for the 2015–16 season after Emmanuel Adebayor left the club and the number was vacated. Manchester City’s Sergio Agüero also did a similar switch in jersey number, from number 16 in 2014–15 to number 10 in 2015–16, a number he took over from Edin Džeko following his loan departure to Roma. During the 1990s, David Beckham wore a different shirt number for Manchester United during four consecutive seasons. He was assigned with the number 28 shirt for the 1993-94 season and retained it for the 1994-95 season, before switching to the number 24 shirt for the 1995-96 season, when he established himself as a regular player. He then switched to the number 10 shirt for the 1996-97 season, and following the retirement of Eric Cantona at the end of that season, he switched to the number 7 shirt for the 1997-98 season, with new signing Teddy Sheringham taking the number 10 shirt.

Some players keep the number they start their career at a club with, such as Chelsea defender John Terry, who wore the number 26 during his long spell at the club, rather than adopting a number 4, 5 or 6 shirt which he might have been expected to take on once he was established as a regular player. On occasion, players have moved numbers to accommodate a new player; for example, Chelsea midfielder Yossi Benayoun handed new signing Juan Mata the number 10 shirt, and changed to the number 30, which doubles his «lucky» number 15.[20] Upon signing for Everton in 2007, Yakubu refused the prestigious number 9 shirt and asked to be assigned number 22, setting this number as a goal-scoring target for his first season,[21] a feat he ultimately fell one goal short of achieving.

In a traditional 4–4–2 system in the UK, the squad numbers 1–11 would usually have been occupied in this manner:

- 1 Goalkeeper

- 2 Right back

- 3 Left back

- 4 Central midfielder (more defensive)

- 5 Centre back

- 6 Centre back

- 7 Right winger

- 8 Central midfielder (more attacking/Box-to-Box)

- 9 Striker (usually a target player)

- 10 Centre-forward (usually a fast poacher)

- 11 Left winger

However, in a more modern 4–2–3–1 system, they will be arranged like this:

- 1 Goalkeeper

- 2 Right back

- 3 Left back

- 4 Central midfielder (more defensive)

- 5 Centre back

- 6 Centre back

- 7 Right winger

- 8 Central midfielder (box-to-box)

- 9 Striker

- 10 Central midfielder (more attacking)

- 11 Left winger

Higher-level clubs have a tendency to field reserve and fringe players in the English Football League Cup as well as insignificant games near the end of the league campaign when there are no major issues (eg a league title, European place or promotion or relegation issues) to be decided, so high squad numbers are not uncommon. Nico Yennaris wore 64 for Arsenal in the competition on 26 September 2012 in a match against Coventry City[22] and on 24 September 2014, again in the League Cup, Manchester City forward José Ángel Pozo wore the number 78 shirt in a match against Sheffield Wednesday.[23] In a quarter-final tie on 17 December 2019, Liverpool player Tom Hill became the first player in English football history to wear the number 99 shirt in a competitive match.[24] In The Football League, the number 55 has been worn by Ade Akinbiyi for Crystal Palace,[25] and Dominik Werling for Barnsley.[26]

When Sunderland signed Cameroonian striker Patrick Mboma on loan in 2002, he wanted the number 70 to symbolize his birth year of 1970. The Premier League refused, however, and he wore the number 7 instead.[27]

England[edit]

Evolution from 2–3–5 to 4–4–2

In England, in a now traditional 4–4–2 formation, the standard numbering is usually: 2 (right fullback), 5, 6, 3 (left fullback); 4 (defensive midfielder), 7 (right midfielder), 8 (central/attacking midfielder), 11 (left midfielder); 10 (second/support striker), 9 (striker). This came about based on the traditional 2–3–5 system. Where the 2 fullbacks retained the numbers 2, 3. Then of the halves, 4 was kept as the central defensive midfielder, while 5 and 6 were moved backward to be in the central of defence. 7 and 11 stayed as the wide attacking players, whilst 8 dropped back a little from inside forward to a (sometimes attacking) midfield role, and 10 stayed as a second striker in support of a number 9. The 4 is generally the holding midfielder, as through the formation evolution it was often used for the sweeper or libero position. This position defended behind the central defenders, but attacked in front – feeding the midfield. It is generally not used today, and developed into the holding midfielder role.

When substitutions were introduced to the game in 1965, the substitute typically took the number 12; when a second substitute was allowed, they wore 14. Players were not compelled to wear the number 13 if they were superstitious.

United States and Canada[edit]

North American professional association football club follows a model similar to that of European clubs, with the exception that many American and Canadian clubs do not have «reserve squads», and thus do not assign higher numbers to those players.

Most American and Canadian clubs have players numbered from 1 to 30, with higher numbers being reserved for second and third goalkeepers. In the United Soccer Leagues First Division and Major League Soccer (MLS), there were only 20 outfield players wearing squad numbers higher than 30 on the first team in the 2009 season, suggesting that the traditional model has been followed.

In 2007, MLS club LA Galaxy retired the former playing number of Cobi Jones, number 13, becoming the first MLS team to do so.

In 2011, MLS club Real Salt Lake retired the former playing number of coach Jason Kreis, number 9.[28]

Goalkeeper numbering[edit]

The first-choice goalkeeper is usually assigned the number 1 shirt as he or she is the first player in a line-up.[1]

The second-choice goalkeeper wears, on many occasions, shirt number 12 which is the first shirt of the second line up, or number 13. In the past, when it was permitted to assign five substitute players in a match, the goalkeeper would also often wear the number 16, the last shirt number in the squad. Later on, when association football laws changed and it was permitted to assign seven substitute players, second-choice goalkeepers often wore the number 18. In the A-League, second-choice goalkeepers mostly wear number 20, based on that competition having a 20-man regulated «first team» squad size.

In international tournaments (such as FIFA World Cup or continental cups) each team must list a squad of 23 players, wearing shirts numbered 1 through 23. Thus, in this case, third-choice goalkeepers often wear the number 23. Prior to the 2002 FIFA World Cup, only 22 players were permitted in international squads; therefore, the third goalkeeper was often awarded the number 22 jersey in previous tournaments.

The move to a fixed number being assigned to each player in a squad was initiated for the 1954 World Cup where each man in a country’s 22-man squad wore a specific number for the duration of the tournament. As a result, the numbers 12 to 22 were assigned to different squad players, with no resemblance to their on-field positions. This meant that a team could start a match not necessarily fielding players wearing numbers one to eleven. Although the numbers one to eleven tended to be given to those players deemed to be the «first choice line-up», this was not always the case for a variety of reasons – a famous example was Johan Cruyff, who insisted on wearing the number 14 shirt for the Netherlands.

In the 1958 World Cup, the Brazilian Football Confederation forgot to send the player numbers list to the event organization. However, the Uruguayan official Lorenzo Villizzio assigned random numbers to the players. The goalkeeper Gilmar received the number 3, and Garrincha and Zagallo wore opposite winger numbers, 11 and 7, while Pelé was randomly given the number 10, for which he would become famous.[29][30]

Argentina defied convention by numbering their squads for the 1978, 1982 and 1986 World Cups alphabetically, resulting in outfield players (not goalkeepers) wearing the number 1 shirt (although Diego Maradona was given an out-of-sequence number 10 in both 1982 and 1986 while Mario Kempes in 1982 and Jorge Valdano in 1986 were allowed to use number 11).[31] In 1974 Argentina also used the alphabetical system, but only to line players and goalkeepers Daniel Carnevali and Ubaldo Fillol wore traditional goalkeeping numbers 1 and 12 respectively. England used a similar alphabetical scheme for the 1982 World Cup, but retained the traditional numbers for the goalkeepers (1, 13 and 22) and the team captain (7), Kevin Keegan.[32] In the 1990 World Cup, Scotland assigned squad numbers according to the number of international matches each player had played at the time (with the exception of goalkeeper Jim Leighton, who was assigned an out-of-sequence number 1): Alex McLeish, who was the most capped player, wore number 2, whereas Robert Fleck and Bryan Gunn, who only had one cap each, wore numbers 21 and 22, respectively. In a practice that ended after the 1998 World Cup, Italy gave low squad numbers to defenders, medium to midfielders, and high ones to forwards, while numbers 1, 12 and 22 were assigned to goalkeepers.[33][34] In July 2007, a FIFA document issuing regulations for the 2010 World Cup finally stated that the number 1 jersey must be issued to a goalkeeper.[35]

Before the 2002 World Cup, the Argentine Football Association (AFA) attempted to retire the number 10 in honour of Maradona by submitting a squad list of 23 players for the tournament, listed 1 through 24, with the number 10 omitted. FIFA rejected Argentina’s plan, with the governing body’s president Sepp Blatter suggesting the number 10 shirt be instead given to the team’s third-choice goalkeeper, Roberto Bonano. The AFA ultimately submitted a revised list with Ariel Ortega, originally listed as number 23, as the number 10.[36]

In early era of Chinese football, number 0 was often assigned to a substitute goalkeeper. At least 4 goalkeepers had been recorded wearing number 0 on field during the early years of professional league of China: Zhao Lei from Sichuan Quanxing, Wang Zhenjie from August 1, Li Jiming from Tianjin Lifei and Li Yun from Shanghai Yuyuan.

Unusual or notable numbers[edit]

- Hicham Zerouali was allowed to wear the number 0 for Scottish Premier League club Aberdeen after the fans nicknamed him «Zero».[37]

- Outfield players have occasionally worn the number 1 for their clubs, including Pantelis Kafes for Olympiacos and AEK Athens, Charlton Athletic’s Stuart Balmer in the 1990s,[38] Sliema Wanderers’ David Carabkott in 2005–06, Partizan’s Simon Vukčević in 2004–05, Beşiktaş’s Daniel Pancu in 2005–06, Atlético Mineiro’s Diego Souza in 2010 and Barnet player-manager Edgar Davids in 2013–14.[39]

- Also in 2001, Argentinian goalkeeper Sergio Vargas wore number 188 for Universidad de Chile, as part of a commercial agreement with telecommunications brand Telefónica CTC Chile.[40] However, the number was not allowed in international competitions, in which Vargas was forced to wear number 1.[41]

- Italian goalkeeper Cristiano Lupatelli wore number 10 while playing for Chievo Verona, between 2001 and 2003. Lupatelli himself admitted that he did it just for fun and due to a bet he made with his friends.[42]

- In 2004, Porto goalkeeper Vítor Baía became the first player to wear 99 in the final of a major European competition, donning the kit in the 2004 UEFA Champions League Final.[43]

- During the 1990s and early 2000s, number 58 was somewhat common among players based in or native to western Mexico, especially the city of Guadalajara. It started as a publicity stunt by radio station XEAV-AM (580 AM), branded as Canal 58.[44] Some notable players to use number 58 were Jared Borgetti, Juan Pablo Rodríguez, Carlos Turrubiates, Eric Wynalda, Hugo Norberto Castillo, Darío Franco, Carlos María Morales, Osmar Donizete, and Benjamín Galindo.

- Chilean striker Marco Olea wore number 111 for Universidad de Chile during the 2005 season. Originally wearing number 11, he decided to give his number to Marcelo Salas upon his arrival to the club.[45]

- Parma goalkeeper Luca Bucci wore the numbers 7 (2005–06) and 5 (2006–07 and 2007–08).[46]

- Iván Zamorano wore number «1+8», or number 18 with a plus symbol between the two digits, for Internazionale from 1997 to 2000, after his number 9 was given to Ronaldo.[47]

- Derek Riordan was given squad number 01 by Hibernian in the 2008–09 season. Number 10 had already been taken by Colin Nish, and none of the club’s goalkeepers had been allocated number 1.[48]

- In 2008, Milan’s three new signings each chose a number indicating the year of his birth: 76 (Andriy Shevchenko, born 1976), 80 (Ronaldinho, born 1980) and 84 (Mathieu Flamini, born 1984).[49]

- The Asian Football Confederation (AFC) once required players to keep the same squad numbers throughout the qualification rounds for the AFC Asian Cup,[50] resulting in players with squad numbers of 100 or higher, most notably the number 121 worn by Thomas Oar of Australia in the 2011 AFC Asian Cup qualifier match against Indonesia.[51]

- Gary Hooper wore shirt number 88 at Celtic as his number 10 was already taken and 88 is the year (1988) he was born in. «88» (1888) is also the year Celtic was founded.[52] The season after Hooper signed, new signing Victor Wanyama chose the number 67 to honour the Lisbon Lions, Celtic’s European Cup winning team of 1967.

- Mexican goalkeeper Guillermo Ochoa wore the number 8 shirt for Standard Liège in his first season at the club.[53] His last name (Ochoa) is similar to the Spanish word for «8» (ocho). He also wore the number 6 in his second stint for Club America in his first season at the club, as his traditional number 13 was taken by Leonel López. He chose the number 6 because that was the date his niece was born, and it was the day he signed for Club America.[54]

- When Róger Guedes signed for Sport Club Corinthians Paulista, he chose the number 123. He chose this because the numbers go 1, 2, 3…, because he has been wearing 23 for years and now that he has a son he wants to begin a new chapter of his life, which includes a new number, but still wants to retain some connection, and also because Fagner Conserva Lemos was already wearing the 23.[55] On substitution boards, it will show 12 or 23 and someone will tell Guedes that he is going on/off.

- When Andrés Iniesta left FC Barcelona in 2018, a special «#Infinit8Iniesta» shirt was released. Although Iniesta never wore it in a match, it was sold to fans. The number on the back, instead of 8, was an infinity symbol (∞).[56]

Commemorative numbers[edit]

Steven Gerrard of Liverpool wearing 08 in the Merseyside derby in March 2006, to commemorate the City of Liverpool becoming the 2008 European Capital of Culture.

- Jesús Arellano, when playing for Club de Futbol Monterrey, wore the number 400 in 1996 to celebrate the city’s 400th anniversary.[57]

- Brazilian Goiás goalkeeper Harlei wore number 400 in a match in 2006, to celebrate his 400th match for the team.[58]

- Brazilian Santos goalkeeper Fábio Costa wore number 300 in a match in 2008 to celebrate his 300th match for the team.[59]

- Andreas Herzog wore the number 100 on his 100th match for the Austrian national team, a friendly against Norway, as he was the first Austrian player to have 100 caps.[60]

- James Beattie of Everton and Steven Gerrard of Liverpool both wore the double-digit 08 instead of the single-digit 8 in the Merseyside derby on 25 March 2006, to commemorate the City of Liverpool becoming the European Capital of Culture for 2008.[61]

- Tugay Kerimoğlu wore the number 94 on his 94th and final cap for Turkey against Brazil in 2007.[62]

- Rubén Sosa wore number 100 for the 100th Anniversary of Nacional on 14 May 1999.[63]

- In 1999, Pablo Bengoechea wore number 108 for the 108th Anniversary of Peñarol.[64]

- During his record-breaking 618th game for São Paulo, Rogério Ceni wore number 618, the highest number ever worn in professional football until 2015.[47]

- During his last match, number 100, for the Danish national team, Martin Jørgensen wore shirt number 100.[65]

- During his record-breaking 100th cap for South Africa, Aaron Mokoena wore shirt number 100.[66]

- In 2011, Vasco da Gama’s heroes Felipe and Juninho Pernambucano wore the number 300—in different matches—to celebrate their 300th matches for the club.[67][68]

- Vasco captain Juninho wore the number 114 against Clássico dos Gigantes rivals Fluminense for the 114th anniversary of the club in 2012.[69]

- Goalkeeper Victor of Atlético Mineiro wore the 2019 shirt in July 2015 celebrating his contract renewal until 2019.[70]

- In 2021, Chilean goalkeeper Claudio Bravo wore number 22 in a friendly match against Bolivia, as a tribute to former goalkeeper Mario Osbén, who died a few days before the match.[71]

See also[edit]

- List of retired numbers in association football

- Number (sports)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Khalil Garriot (21 June 2014). «Mystery solved: Why do the best soccer players wear No. 10?». Yahoo. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b El número 10, la camiseta que se convirtió en un emblema by Leonardo Peluso on Página/12, 3 February 2018

- ^ The Secret Lives of Numbers: The Curious Truth Behind Everyday Digits by Michael Millar, Virgin Books, 2012 – ISBN 978-0753540862

- ^ Así nació la tradición de usar números en las camisetas by Gustavo Farías on La Voz del Interior, 22 August 2013

- ^ Cavallini, Rob (2007). Play Up Corinth: A History of The Corinthian Football Club. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7524-4479-6.

- ^ a b c d Historia y curiosidades de la numeración fija en el fútbol by Walter Raiño on Clarín, 13 September 2017

- ^ soccermavn (16 December 2012). «1924 U.S. Open Cup Final Fall River @ Vesper Buick (St. Louis)». Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Gunners wear numbered shirts», Arsenal.com, 6 July 2007

- ^ a b The ‘most novel cup final in the history of football’ By Gareth Thomas on The Football History Boys — April 14, 2020

- ^ De ‘Nuestro Hirosima’ al surgimiento de los números como dorsales by Javier Estepa on Marca

- ^ «1–11 in the Premier League era». wordpress.com. 14 October 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «ron pavey – The Goldstone Wrap». thegoldstonewrap.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Salvemos al 4: la desaparición de los laterales». www.elgrafico.com.ar. Retrieved 4 April 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «lateral izquierdo, ¿una especie en extinción?». infobae.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «número 5: Volante tapón-mediocampista central». obolog.es. Retrieved 4 April 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Traynor, Mikey. «Hate Mental Squad Numbers? You’ll Love Ligue 1’s Reasoning For Not Letting Balotelli Wear #45». balls.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «No 10 shirt downsized – Football Italia». www.football-italia.net. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Jonathan De Guzman to wear the No.1 shirt at Chievo». espnfc.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «New squad numbers for title heroes». Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ «Deco’s Top 20». Chelsea FC. 17 July 2008.

- ^ Ian Doyle. «Daily Post North Wales – Sport News – Everton FC – Yakubu aims to snatch 22». Dailypost.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Arsenal 6–1 Coventry». BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ «Manchester City 7–0 Sheffield Wednesday». BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ «Aston Villa v Liverpool». BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Rivals Archived 26 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Crazy squad number XI – Who Ate all the Pies». Who Ate all the Pies. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Sunderland Deny Phillips for Sale». The Northern Echo. 17 February 2002.

- ^ «Real Salt Lake retires Jason Kreis’ number in unprecedented move». AOL Sporting News. 5 July 2011.

- ^ Soccer and World Cup Trivia & Curiosities Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Mienet.com. Accessed 7 January 2009.

- ^ MSN – Copa 2006 – Curiosidades / Copa de 1958 Archived 10 January 2008 at Wikiwix

- ^ «Argentina squad 1982 World Cup». fifa.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Young, Peter. «England in the World Cup – 1982 Final Squad». www.englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Italy squad 1998 World Cup». fifa.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Italy squad 1994 World Cup». fifa.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Regulations of 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa (point 4 of Article 26)» (PDF). fifa.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Ortega fills Maradona’s shirt». BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 May 2002.

- ^ Zerouali killed in car accident BBC News, 6 December 2004

- ^ Murray, Scott (30 May 2001). «A tale of strips, stripes and strops». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Peck, Bruce (28 July 2013). «Barnet player-manager Edgar Davids to ‘start trend’ by wearing No. 1 shirt in midfield». Dirty Tackle. Yahoo! Sports.

- ^ «Columna: Vargas se cuida las espaldas». El Mercurio (in Spanish). 15 February 2001. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ «Polémica publicitario-deportiva por el «188»» (in Spanish). adlatina.com. 12 March 2001. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ «Il 5, l’8 o il 10. Portiere, ma che numero di maglia porti?» [The 5, the 8 or the 10. Goalkeeper, but what jersey number are you wearing?] (in Italian). Sky Sport (Italy). 15 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

In his two seasons at Chievo, Lupatelli always played with 10. He himself explains why. «A bet with friends. It all started as a joke, and it became reality. I think it’s a funny and nice thing»

- ^ «Monaco-Porto 2003 History». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Herrera Borja, Antonio. ««58»: El final de una era». Tocando el Balón. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ «Marco Olea recuerda su goleador paso por la U y cuenta su pasión por la cocina» (in Spanish). Chilevisión. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ «Luca Bucci». weltfussball.de. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b «Serie A – Ronaldinho plays numbers game». Eurosport. 22 July 2008.

- ^ Hibernian return delights Riordan, BBC Sport, 2 September 2008.

- ^ Marcotti, Gabriele (23 October 2008). «Becks leaving MLS? Say it ain’t so!». Inside Soccer. SI.com.

- ^ «Regulations: AFC Asian Cup 2011 – Qualifiers» (PDF). Asian Football Confederation. p. 37. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ^ «Socceroos storm into Asian Cup». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 March 2010.

- ^ «Hooper to wear number 88 for Celtic». STV Sport. Scotland. 27 July 2010.

- ^ «Guillermo Ochoa». Standard de Liège. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ «¿Por qué Memo Ochoa usa el número ‘6’ con América? | Goal.com». www.goal.com. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ «Roger Guedes explains the choice of number 123 at Corinthians and promises: ‘You can expect a lot of competition’«.

- ^ «The #Infinit8Iniesta jersey, on sale now!».

- ^ «Regresó la camiseta ‘400’ a manos de Jesús Arellano». mediotiempo.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Recordista no Goiás, Harlei lança c… | Noticias — Universidade do Futebol». Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ «GloboEsporte.com > Futebol > Santos – NOTÍCIAS – Fábio Costa comemora 300 jogos pelo Peixe com uniforme especial». globoesporte.globo.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Strecha, Alexander. «FIFA macht Ausnahme bei Herzog – ÖFB-Teamkapitän wird gegen Norwegen mit der Rückennummer 100 sein Jubiläum feiern». wienerzeitung.at. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Liverpool 3–1 Everton». BBC News. 25 March 2006. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ «Tugay bows out in stalemate». rovers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Ídolos del Club Nacional de Football – Deportes». taringa.net. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Pablo Javier Bengoechea». padreydecano.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Martin Jørgensen med nummer 100 på ryggen – Øvrig landsholdsfodbold – danske og udenlandske fodboldnyheder fra». Onside.dk. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Aaron Mokoena vs Guatemala, 2010». gettyimages.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ «Veja a camisa nº 300 que Felipe usará no jogo contra o Náutico». Netvasco. 27 April 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Juninho fala da alegria pelos 300 jogos e Vasco prepara camisa especial». Netvasco. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Escolhido por torcedores, Juninho usará camisa 114 em clássico». Gazeta Esportiva. 25 August 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ «Pacotão do Galo tem noche de Pratto, Victor 2019 e novo manto All Black». globoesporte.com. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Ovalle, Christian (26 March 2021). «Claudio Bravo usará ante Bolivia número en homenaje a Mario ‘el Gato’ Osbén» [Claudio Bravo will use against Bolivia a special number as a tribute to Mario ‘the Cat’ Osbén]. Radio Bío-Bío (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 October 2021.

Squad numbers are used in association football to identify and distinguish players that are on the field. Numbers very soon became a way to also indicate position, with starting players being assigned numbers 1–11, although in the modern game they are often influenced by the players’ favourite numbers and other less technical reasons, as well as using «surrogates» for a number that is already in use. However, numbers 1–11 are often still worn by players of the previously associated position.[1]

As national leagues adopted squad numbers and game tactics evolved over the decades, numbering systems evolved separately in each football scene, and so different countries have different conventions. Still, there are some numbers that are universally agreed upon being used for a particular position, because they are quintessentially associated with that role.[1]

For instance, «1» is frequently used by the starting goalkeeper, as the goalkeeper is the first player in a line-up.[1] It is also the only position on the field that is required to be occupied. «10» is one of the most emblematic squad numbers in football,[2] due to the sheer number of football legends that used the number 10 shirt; playmakers, second strikers, centre-forwards and attacking midfielders usually wear this number.[1] «7» is often associated with effective and profitable wingers or second strikers.[1] «9» is usually worn by strikers, who hold the most advanced offensive positions on the pitch, and are often the highest scorers in the team.[1]

History[edit]

First use of numbers[edit]

First use of numbers in South America: Third Lanark and Argentine «Zona Norte» combined entering to the pitch with numbered jerseys, 10 June 1923

Arsenal FC wearing numbered shirts in a friendly v FC Vienna in 1933. Numbered shirts had first appeared in England in 1928 when Arsenal played Sheffield Wednesday. Their use would not be ruled mandatory until 1939

The first record of numbered jerseys in football date back to 1911, with Australian teams Sydney Leichardt and HMS Powerful being the first to use squad numbers on their backs.[3] One year later, numbering in football would be ruled as mandatory in New South Wales.[4]

The next recorded use was on 23 March 1914, when the English Wanderers, a team of amateur players from Football League clubs, played Corinthians at Stamford Bridge, London. This was Corinthians first match after their FA ban for joining the Amateur Football Association was rescinded. Wanderers won 4–2.[5]

In South America, Argentina was the first country with numbered shirts. It was during the Scottish team Third Lanark tour to South America of 1923, they played a friendly match v a local combined team («Zona Norte») on 10 June. Both squads were numbered from 1–11.[2]

30 March 1924, saw the first football match in the United States with squad numbers, when the Fall River Marksmen played St. Louis Vesper Buick during the 1923–24 National Challenge Cup, although only the local team wore numbered shirts.[6][7]

The next recorded use in association football in Europe was on 25 August 1928 when The Wednesday played Arsenal[8] and Chelsea hosted Swansea Town at Stamford Bridge. Numbers were assigned by field location:

- Goalkeeper

- Right full back (right side centre back)

- Left full back (left side centre back)

- Right half back (right side defensive midfield)

- Centre half back (centre defensive midfield)

- Left half back (left side defensive midfield)

- Outside right (right winger)

- Inside right (attacking midfield)

- Centre forward

- Inside left (attacking midfield)

- Outside left (left winger)

In the first game at Stamford Bridge, only the outfield players wore numbers (2–11). The Daily Express (p. 13, 27 August 1928) reported, «The 35,000 spectators were able to give credit for each bit of good work to the correct individual, because the team were numbered, and the large figures in black on white squares enabled each man to be identified without trouble.» The Daily Mirror («Numbered Jerseys A Success», p. 29, 27 August 1928) also covered the match: «I fancy the scheme has come to stay. All that was required was a lead and London has supplied it.» When Chelsea toured Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil at the end of the season in the summer of 1929, they also wore numbered shirts, earning the nickname «Los Numerados» («the numbered») from locals.

A similar numbering criteria was used in the 1933 FA Cup Final between Everton and Manchester City.[9] Nevertheless, it was not until the 1939–40 season when The Football League ruled that squads had to wear numbers for each player.[9][6]