История изобретения радио. Что такое радио, принцип работы

Радио – это средство передачи на расстояние сообщений, новостей, музыки, то, что многие слушают дома, в автомобиле или на работе. Невозможно представить нашу жизнь без такого привычного звукового вещания, как радиопередача. Но мало кто задумывался, как появилось это изобретение, и кто первый придумал радио. В этой статье расскажу про историю радио и ученых, которые внесли свой вклад в появление устройства, которое навсегда изменило мир.

История изобретения радио

Открытие электромагнитного поля в 1845 году, к которому долго шел английский ученый-физик М. Фарадей, стало сенсацией 19 века. Спустя два десятилетия, тоже англичанин – Д. К. Максвелл теоретически обосновал и сформулировал существование электромагнитных волн, одним из видов которых являются радиоволны. Человек их не видит и не ощущает, поэтому без обоснования теории электродинамики было бы невозможно создание самого радиоприемника.

Эти два открытия и послужили отправной точкой изобретения радио, хотя не сразу были приняты научным сообществом. Было сделано множество работ и изобретений. Только по прошествии еще двадцати лет, в 1886-88 годах, немецкий ученый Генрих Герц поставил удачный эксперимент с простым прибором, состоящим из генератора и резонатора, и зафиксировал излучение электромагнитных волн на короткое расстояние. Но практического применения этой конструкции Г. Герц не видел.

Генрих Рудольф Герц

Физики разных стран год за годом проводили эксперименты по усовершенствованию электромагнитных волновых приемников и расширению диапазона передачи сигнала. Среди этих ученых были Т. Эдисон в 1876-85 годах, О. Лодж и Э. Бранли в 1889-90 годах, Н. Тесла в 1891-93 годах, индийский физик Д. Чандра Бозе в 1894 году и многие другие

Первое радио Попова

Кто первый создатель радио

Ученые всего мира искали способы передачи сигналов на расстояние. Изобретателями радиоприемника по праву считают нескольких претендентов, которые работали одновременно, но никак не были связаны между собой. Эти фамилии многие знают – русский ученый Александр Попов, американец Никола Тесла, итальянский предприниматель . Гульельмо Маркони.

Н. Тесла первым запатентовал свое изобретение, которое использовалось для дальнейшего развития радиосвязи. Он продемонстрировал, как генератор переменного тока производит колебания токов высокой, для того времени, частоты, и метод подавления звука при помощи этих частот. Он первым зафиксировал явление электрического резонанса. Весной 1891 года Н. Тесла получил американский патент на свой инновационный метод.

Уже в 1893 году американский ученый читает лекции и демонстрирует как при помощи резонанс-трансформатора можно передавать электрические сигналы в эфир. Он доказывает, что эту техническую систему можно использовать для беспроводной связи.

Никола Тесла

Российскому физико-химическому сообществу Александр Попов читал доклад весной 1895 года и тогда продемонстрировал усовершенствованный прибор О. Лоджа. Позднее, в 1896 году, русский ученый опубликовал статью в научном издании о создании им в 1895 году прибора приема электромагнитных колебаний на расстояние до 60 м, который в дальнейшем может быть применен для передачи сигналов на большие расстояния.

В марте 1897 года на очередной лекции А. Попов демонстрирует передачу и прием сигнала в стенах здания. Продолжая работу над изобретением телеграфного беспроводного передатчика, уже в декабре того же года русский ученый успешно производит прием сигнала из четырех букв «ГЕРЦ» на расстояние более 250 м от передающей станции. Но А. Попов был практик и не стремился фиксировать свои достижения перед мировым ученым сообществом.

В Италии Гульельмо Маркони так же работает над созданием передачи и приема телеграфного сигнала, и весной 1895 года провел эксперимент передачи сигнала на несколько сотен метров. Летом 1896 года итальянский предприниматель подает заявку на получение патента Великобритании на изобретение своей аппаратуры. В сентябре он успешно демонстрирует прием сигнала на расстояние до 2,5 км. В июле 1897 года Маркони получает патент, оформленный от 2 июня 1896 года.

Гульельмо Маркони

Принцип работы радио

Радио – это первая беспроводная связь. Носителем сигнала являются радиоволны, распространяющиеся в пространстве. Это невероятно простое устройство, которые используется в разных ситуациях. Например, радио-няня – маленький аппарат в детской комнате принимает звук и передает его родителям, находящимся в другом помещении. По такой связи можно отправлять не только звуковые сигналы, но и изображения на огромные расстояния.

У термина «радио» есть несколько значений. Во-первых – само устройство, для приема звуковых передач. Во-вторых – область науки или техники, которые занимаются изучением передачи и приема радиоволн.

Впервые, в радиоприемнике, изобретенном А. Поповым для Российского военно-морского флота, был применен когерер – прибор, чувствительный к электромагнитным волнам. Один вывод когерера был заземлен, другой, присоединен к проволоке и высоко поднят.

Схема радио Попова

Устройство первого радиоприемника А. Попова имеет следующие детали:

- электромагнитное реле;

- батарея (источник постоянного тока);

- антенный провод;

- когерер;

- молоточек звонка;

- чашечка звонка;

- электромагнит звонка.

Принцип работы таков:

1) Высокочастотные колебания формируются в радиопередатчике – это несущий сигнал или несущая частота, на которую накладывается информация и происходит модуляция с помощью электрических колебаний низкой частоты. Антенна передает в эфир радиоволны (модулированный сигнал).

2) Приемная антенна находит модулированные сигналы и отправляет в радиоприемник.

3) Детектор в приемнике выделяет полезный сигнал нужной несущей частоты из множества радиосигналов от разных радиопередатчиков.

Появление термина «broadcasting»

Термин – бродкастинг («broadcasting», англ. яз.) появился в начале прошлого века. Broadcasting переводится как широкий разброс, распространение, а позднее закрепилось значение – радиовещание, телевещание, трансляция, широковещание.

Существует история появления этого термина в индустрии трансляций радио и телевидения:

В 1909 году калифорнийский преподаватель колледжа электроники, изобретатель Ч. Геррольд создает радиостанцию. Он использует технологию с искровым разрядником. Несущая частота модулируется голосом, позже еще и музыкой. Его музыкальные и новостные передачи сначала слушали ученики и выпускники колледжа.

Чарльз Геррольд за работой на радиостанции

Изобретатель был сыном фермера и использовал сельскохозяйственный термин – «broadcasting», который означает «рассеивание семян по полю, в разных направлениях», для определения радиоволновой передачи. Он ввел слова:

«narrowcasting» – узкое распространение, один получатель;

«broadcasting» – широкое распространение, массовая аудитория.

Развитие радио и радиовещания

В 1897 году Г. Маркони сделал существенный прорыв в развитии радиовещания. Он соединил приемник с телеграфным аппаратом, а передатчик с ключом Морзе, и получил радиотелеграфическую связь. По его мнению, антенны приёмника и передатчика должны были быть одной длины, что повышало мощность передатчика. К тому же, А. Попов отмечал лучшую чувствительность детектора Гульельмо Маркони.

В 1898 году итальянский изобретатель первым находит возможность настройки радио (патент получен в 1900 году). Тогда он открывает в Великобритании свой первый «завод беспроволочного телеграфа».

В конце 1898 года, француз Э. Дюкретэ начинает мало-серийный выпуск приемников системы А. Попова.

Приборы, созданные на заводе Э. Дюкретэ, успешно используются на Черноморском флоте и в других спасательных морских операциях России. В 1900 году радиотелеграфные сообщения передавались между севшим на мель российским броненосцем, радиостанцией острова Гогланд, военно-морской базой в Котке, Адмиралтейством в Санкт-Петербурге. В результате обмена радиограммами – ледокол «Ермак» пришел на помощь кораблю, а также спас финских рыбаков на оторвавшейся льдине.

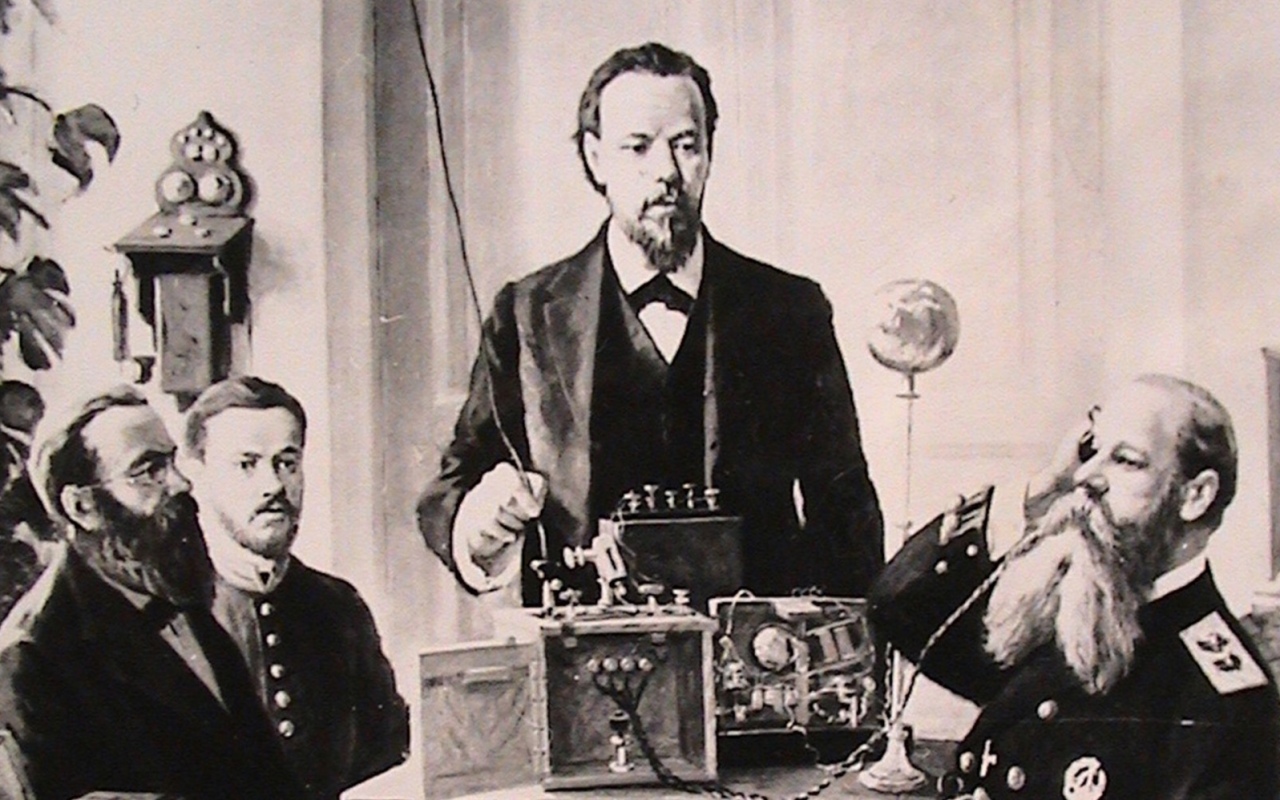

Радиомастерская в Кронштадте. Александр Попов (справа)

В 1906 году ученые-изобретатели Р. Фессенден и Л. Форест обнаружили принцип амплитудной модуляции радиосигнала низкочастотным сигналом. Это сделало возможным передавать человеческую речь и музыку в эфире. 24 декабря корабли в море услышали Р. Фессендена – он читал отрывки из библии и играл на скрипке.

В 1907 году Г. Маркони создал постоянно действующую телеграфную линию между Ирландией и Шотландией.

В 1909 году за выдающийся вклад в развитие беспроводной телеграфии Г. Маркони становится лауреатом Нобелевской премии.

Холодный апрель 1912 года. Пассажирский лайнер «Титаник» вышел в свое первое и последнее плавание. Он был оснащен самыми современными комплектами искровых станций беспроводной телеграфии «Международной компании морской связи Маркони». В начале прошлого столетия корабельные радиостанции передавали сообщения на расстояние около 200 километров. Радиопередатчик «Титаника» был верхом технической мысли того времени. Сигнал уверено уходил на 800 километров днем, а ночью распространялся до 3 тысяч километров. Богатые пассажиры с удовольствием пользовались техническим новшеством и рассылали телеграммы своим родственникам прямо с борта «Титаника».

Ночью произошло столкновение с огромной льдиной, и в эфире впервые прозвучал тревожный сигнал «SOS». Ледяная вода заполняла нижние отсеки лайнера, людей сажали в шлюпки, которых на всех не хватало, на палубе началась паника. Почти через два часа после полного погружения судна на место кораблекрушения прибыл пароход «Карпатия» и подобрал людей из шлюпок. Благодаря радиотелеграфии были спасены жизни более 700 человек. Вот пример того, что радиосвязь необходима в любой ситуации.

Радиовещание в СССР

В Советской России первые опытные радиотрансляции в 1919 году проводились в Нижнем Новгороде, в 1920 году в Москве, Казани и нескольких больших городах. В 1921 году была принята программа по организации радиовещания в крупных городах и уездных центрах. В конце сентября в Москве начал работать первый радиоузел. Так внедрилось постоянное массовое вещание радиопередач по уличным громкоговорителям в СССР.

В 1922 году в нашей столице на Шаболовке было завершено строительство самой высокой в СССР 160-метровой башни, позднее названной в честь архитектора В. Шухова. Весной на Шуховскую башню установили мощные радиопередатчики, а к концу лета начали осуществлять пробные передачи для населения страны.

Шуховская башня. 1922 год

В тридцатые годы прошлого века радиовещание сыграло большую роль в патриотическом воспитании населения, пропаганде передовых методов труда, стахановского движения, организации социалистических соревнований и др.

Со временем были заложены основы радиорепортажа и радиоинтервью, особую популярность приобрел жанр радионовостей. Появились музыкальные, развлекательные, спортивные, детские радиопередачи.

В 1937 году радиовещание перенесено в новый Московский радиодом на Малой Никитской, пущен коротковолновый радиопередатчик.

До ВО войны Советский Союз отставал в развитии радиосвязи от других стран. К 1940 году в США имелось более 50 миллионов радиоприемников, в Англии около 10 миллионов, а во Франции порядка 5 миллионов. На тот момент в СССР существовало 15 радиозаводов, где было выпущено 140 тысяч радиоприемников. К 41-му году насчитывалось около 500 тысяч приборов радиовещания.

В 1941-42 годах, в условиях ВО войны, всего за девять месяцев была построена самая мощная в мире Куйбышевская радиовещательная станция. Это был «Секретный объект №15», на строительство которого из лагерей доставили около двух десятков политзаключенных с техническим, инженерным образованием и связистов. Двухэтажный подземный бункер, где располагалось радиооборудование, до сих пор находится на глубине 22 метров под землей. Первая испытательная передача велась на средних волнах.

Куйбышевская радиовещательная станция. Грузовой вход в техническое здание.

В секретном режиме военного времени на станции в Куйбышеве работал московский диктор Ю. Левитан. Не многие знают, что знаменитую фразу: «Говорит Москва!», он произносил из стен Куйбышевского радиодома.

Основное назначение было вещание на СССР, Европу, Северную Африку и Дальний Восток. Также велись передачи на английском, немецком и французском языках. В ночное время сигнал принимался и в США. Через эту станцию шла связь с резидентурой Юстас-Алексу. На полную мощность радиостанция заработала в 1945 году, а впоследствии названа в честь А. Попова.

Юрий Левитан – диктор Всесоюзного радио Госкомитета СССР

Радиовещание в диапазоне УКВ стало широко внедряться в послевоенные годы. Начинается строительство областных телерадиоцентров, радиофикация колхозов, переход Всесоюзного радио на трехпрограммное вещание.

В период с 1929 по 2014 годы вещание на зарубежные страны велось «Московским радио», преобразованным в 1993 году в «Голос России». С 2014 года иновещание осуществляется радиостанцией Sputnik.

В 2012 году Государственной комиссией по радиочастотам (ГКРЧ) подписан протокол, согласно которому выделяется полоса радиочастот для создания на территории Российской Федерации сетей цифрового радиовещания.

История зарубежного радиовещания

Радиовещание становится средством массовой информации в 1922-23 годах, которое начинает конкурировать с печатными СМИ. Почти во всех странах мира транслируются экспериментальные радиопередачи.

В Америке к концу 1922 года было выдано почти 600 лицензий на право радиовещания. Целью таковой деятельности могло быть освещение новостей в стране, просветительство, религиозные или культурные программы, трансляция концертов и т. п.

BBC: В декабре 1922 года в Великобритании начинает ежедневные передачи на Лондон общественная радиовещательная организация «British Broadcasting Company» (Би-Би-Си), созданная при участии Г. Маркони. Спустя год вещание охватывает Манчестер и Бирмингем.

British Broadcasting Company

URI: В итальянском городе Турин 27 августа 1924 года основан радиофонический союз «Unione radiofonica italiana», при посредничестве британской и американской корпораций: «Radiofono» и «SIRAC». URI был единственным итальянским радиовещателем, имеющим право транслировать новости, представляющие общественный интерес. Первую станцию установили в Риме (1924 год), затем в Милане (1925 год) и в Неаполе (1926 год). Бедной Италии было сложно содержать и развивать радиовещание. Широкое распространение ипродвижение радио получило при фашистском режиме в тридцатые годы.

NBC: в 1926 году в Соединённых Штатах появляется первая крупная радиовещательная сеть, сформированная «Радиокорпорацией Америки» – «National Broadcasting Company» (Эн-Би-Си).

National Broadcasting Company

DW GmbH: в 1926 году появляется немецкая радиокомпания «Deutsche Welle GmbH», которая запускает в том же году внутринемецкую общественную радиостанцию «Deutschlandsender» (Передатчик Германии) на длинных волнах. Летом 1929 году начала вещание на немецком языке коротковолновая радиостанция «Weltrundfunksender» (Мировой радиовещательный передатчик) в направлении всех континентов.

CBS: в 1927 году возникла Колумбийская система фонографического вещания и с 1928 года носит название – «Columbia Broadcasting System». Сеть становится одной из крупнейших радиовещательных, позднее, в 30-х годах входит в Большую тройку американских вещательных телевизионных сетей.

Так, в двадцатые годы прошлого столетия появились две школы радиовещания:

- частное американское радио;

- европейское общественно-правовое радио.

Изобретение радио навсегда изменило историю человечества.

The history of telecommunication began with the use of smoke signals and drums in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. In the 1790s, the first fixed semaphore systems emerged in Europe. However, it was not until the 1830s that electrical telecommunication systems started to appear. This article details the history of telecommunication and the individuals who helped make telecommunication systems what they are today. The history of telecommunication is an important part of the larger history of communication.

Ancient systems and optical telegraphy[edit]

Early telecommunications included smoke signals and drums. Talking drums were used by natives in Africa, and smoke signals in North America and China. These systems were often used to do more than announce the presence of a military camp.[1][2]

In Rabbinical Judaism a signal was given by means of kerchiefs or flags at intervals along the way back to the high priest to indicate the goat «for Azazel» had been pushed from the cliff.

Homing pigeons have occasionally been used throughout history by different cultures. Pigeon post had Persian roots, and was later used by the Romans to aid their military.[3]

Greek hydraulic semaphore systems were used as early as the 4th century BC. The hydraulic semaphores, which worked with water filled vessels and visual signals, functioned as optical telegraphs. However, they could only utilize a very limited range of pre-determined messages, and as with all such optical telegraphs could only be deployed during good visibility conditions.[4]

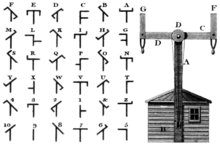

Code of letters and symbols for Chappe telegraph (Rees’s Cyclopaedia)

During the Middle Ages, chains of beacons were commonly used on hilltops as a means of relaying a signal. Beacon chains suffered the drawback that they could only pass a single bit of information, so the meaning of the message such as «the enemy has been sighted» had to be agreed upon in advance. One notable instance of their use was during the Spanish Armada, when a beacon chain relayed a signal from Plymouth to London that signaled the arrival of the Spanish warships.[5]

In 1774, the Swiss physicist Georges Lesage built an electrostatic telegraph consisting of a set of 24 conductive wires a few meters long connected to 24 elder balls suspended from a silk thread (each wire corresponds to a letter). The electrification of a wire by means of an electrostatic generator causes the corresponding elder ball to deflect and designate a letter to the operator located at the end of the line. The sequence of selected letters leads to the writing and transmission of a message.[6]

French engineer Claude Chappe began working on visual telegraphy in 1790, using pairs of «clocks» whose hands pointed at different symbols. These did not prove quite viable at long distances, and Chappe revised his model to use two sets of jointed wooden beams. Operators moved the beams using cranks and wires.[7] He built his first telegraph line between Lille and Paris, followed by a line from Strasbourg to Paris. In 1794, a Swedish engineer, Abraham Edelcrantz built a quite different system from Stockholm to Drottningholm. As opposed to Chappe’s system which involved pulleys rotating beams of wood, Edelcrantz’s system relied only upon shutters and was therefore faster.[8]

However, semaphore as a communication system suffered from the need for skilled operators and expensive towers often at intervals of only ten to thirty kilometers (six to nineteen miles). As a result, the last commercial line was abandoned in 1880.[9]

Electrical telegraph[edit]

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including Laplace, Ampère, and Gauss were involved.

An early experiment in electrical telegraphy was an ‘electrochemical’ telegraph created by the German physician, anatomist and inventor Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring in 1809, based on an earlier, less robust design of 1804 by Spanish polymath and scientist Francisco Salva Campillo.[10] Both their designs employed multiple wires (up to 35) in order to visually represent almost all Latin letters and numerals. Thus, messages could be conveyed electrically up to a few kilometers (in von Sömmerring’s design), with each of the telegraph receiver’s wires immersed in a separate glass tube of acid. An electric current was sequentially applied by the sender through the various wires representing each digit of a message; at the recipient’s end the currents electrolysed the acid in the tubes in sequence, releasing streams of hydrogen bubbles next to each associated letter or numeral. The telegraph receiver’s operator would visually observe the bubbles and could then record the transmitted message, albeit at a very low baud rate.[10] The principal disadvantage to the system was its prohibitive cost, due to having to manufacture and string-up the multiple wire circuits it employed, as opposed to the single wire (with ground return) used by later telegraphs.

The first working telegraph was built by Francis Ronalds in 1816 and used static electricity.[11]

Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke patented a five-needle, six-wire system, which entered commercial use in 1838.[12] It used the deflection of needles to represent messages and started operating over twenty-one kilometres (thirteen miles) of the Great Western Railway on 9 April 1839. Both Wheatstone and Cooke viewed their device as «an improvement to the [existing] electromagnetic telegraph» not as a new device.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Samuel Morse developed a version of the electrical telegraph which he demonstrated on 2 September 1837. Alfred Vail saw this demonstration and joined Morse to develop the register—a telegraph terminal that integrated a logging device for recording messages to paper tape. This was demonstrated successfully over three miles (five kilometres) on 6 January 1838 and eventually over forty miles (sixty-four kilometres) between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore on 24 May 1844. The patented invention proved lucrative and by 1851 telegraph lines in the United States spanned over 20,000 miles (32,000 kilometres).[13] Morse’s most important technical contribution to this telegraph was the simple and highly efficient Morse Code, co-developed with Vail, which was an important advance over Wheatstone’s more complicated and expensive system, and required just two wires. The communications efficiency of the Morse Code preceded that of the Huffman code in digital communications by over 100 years, but Morse and Vail developed the code purely empirically, with shorter codes for more frequent letters.

The submarine cable across the English Channel, wire coated in gutta percha, was laid in 1851.[14] Transatlantic cables installed in 1857 and 1858 only operated for a few days or weeks (carried messages of greeting back and forth between James Buchanan and Queen Victoria) before they failed.[15] The project to lay a replacement line was delayed for five years by the American Civil War. The first successful transatlantic telegraph cable was completed on 27 July 1866, allowing continuous transatlantic telecommunication for the first time.

Telephone[edit]

The master telephone patent, 174465, granted to Bell, March 7, 1876

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of New Haven, Connecticut in the US and London, England in the UK. Alexander Graham Bell held the master patent for the telephone that was needed for such services in both countries.[16] All other patents for electric telephone devices and features flowed from this master patent. Credit for the invention of the electric telephone has been frequently disputed, and new controversies over the issue have arisen from time-to-time. As with other great inventions such as radio, television, the light bulb, and the digital computer, there were several inventors who did pioneering experimental work on voice transmission over a wire, who then improved on each other’s ideas. However, the key innovators were Alexander Graham Bell and Gardiner Greene Hubbard, who created the first telephone company, the Bell Telephone Company in the United States, which later evolved into American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), at times the world’s largest phone company.

Telephone technology grew quickly after the first commercial services emerged, with inter-city lines being built and telephone exchanges in every major city of the United States by the mid-1880s.[17][18][19] The first transcontinental telephone call occurred on January 25, 1915. Despite this, transatlantic voice communication remained impossible for customers until January 7, 1927 when a connection was established using radio.[20] However no cable connection existed until TAT-1 was inaugurated on September 25, 1956 providing 36 telephone circuits.[21]

In 1880, Bell and co-inventor Charles Sumner Tainter conducted the world’s first wireless telephone call via modulated lightbeams projected by photophones. The scientific principles of their invention would not be utilized for several decades, when they were first deployed in military and fiber-optic communications.

The first transatlantic telephone cable (which incorporated hundreds of electronic amplifiers) was not operational until 1956, only six years before the first commercial telecommunications satellite, Telstar, was launched into space.[22]

Radio and television[edit]

Over several years starting in 1894, the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi worked on adapting the newly discovered phenomenon of radio waves to telecommunication, building the first wireless telegraphy system using them.[23] In December 1901, he established wireless communication between St. John’s, Newfoundland and Poldhu, Cornwall (England), earning him a Nobel Prize in Physics (which he shared with Karl Braun) in 1909.[24] In 1900, Reginald Fessenden was able to wirelessly transmit a human voice.

Millimetre wave communication was first investigated by Bengali physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose during 1894–1896, when he reached an extremely high frequency of up to 60 GHz in his experiments.[25] He also introduced the use of semiconductor junctions to detect radio waves,[26] when he patented the radio crystal detector in 1901.[27][28]

In 1924, Japanese engineer Kenjiro Takayanagi began a research program on electronic television. In 1925, he demonstrated a CRT television with thermal electron emission.[29] In 1926, he demonstrated a CRT television with 40-line resolution,[30] the first working example of a fully electronic television receiver.[29] In 1927, he increased the television resolution to 100 lines, which was unrivaled until 1931.[31] In 1928, he was the first to transmit human faces in half-tones on television, influencing the later work of Vladimir K. Zworykin.[32]

On March 25, 1925, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird publicly demonstrated the transmission of moving silhouette pictures at the London department store Selfridge’s. Baird’s system relied upon the fast-rotating Nipkow disk, and thus it became known as the mechanical television. In October 1925, Baird was successful in obtaining moving pictures with halftone shades, which were by most accounts the first true television pictures.[33] This led to a public demonstration of the improved device on 26 January 1926 again at Selfridges. His invention formed the basis of semi-experimental broadcasts done by the British Broadcasting Corporation beginning September 30, 1929.[34]

For most of the twentieth century televisions used the cathode ray tube (CRT) invented by Karl Braun. Such a television was produced by Philo Farnsworth, who demonstrated crude silhouette images to his family in Idaho on September 7, 1927.[35] Farnsworth’s device would compete with the concurrent work of Kalman Tihanyi and Vladimir Zworykin. Though the execution of the device was not yet what everyone hoped it could be, it earned Farnsworth a small production company. In 1934, he gave the first public demonstration of the television at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute and opened his own broadcasting station.[36] Zworykin’s camera, based on Tihanyi’s Radioskop, which later would be known as the Iconoscope, had the backing of the influential Radio Corporation of America (RCA). In the United States, court action between Farnsworth and RCA would resolve in Farnsworth’s favour.[37] John Logie Baird switched from mechanical television and became a pioneer of colour television using cathode-ray tubes.[33]

After mid-century the spread of coaxial cable and microwave radio relay allowed television networks to spread across even large countries.

Semiconductor era[edit]

The modern period of telecommunication history from 1950 onwards is referred to as the semiconductor era, due to the wide adoption of semiconductor devices in telecommunication technology. The development of transistor technology and the semiconductor industry enabled significant advances in telecommunication technology, led to the price of telecommunications services declining significantly, and led to a transition away from state-owned narrowband circuit-switched networks to private broadband packet-switched networks. In turn, this led to a significant increase in the total number of telephone subscribers, reaching nearly 1 billion users worldwide by the end of the 20th century.[38]

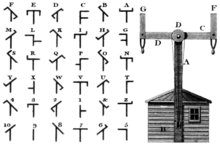

The development of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) large-scale integration (LSI) technology, information theory and cellular networking led to the development of affordable mobile communications. There was a rapid growth of the telecommunications industry towards the end of the 20th century, primarily due to the introduction of digital signal processing in wireless communications, driven by the development of low-cost, very large-scale integration (VLSI) RF CMOS (radio-frequency complementary MOS) technology.[39]

Videotelephony[edit]

The 1969 AT&T Mod II Picturephone, the result of decades long R&D at a cost of over $500M.

The development of videotelephony involved the historical development of several technologies which enabled the use of live video in addition to voice telecommunications. The concept of videotelephony was first popularized in the late 1870s in both the United States and Europe, although the basic sciences to permit its very earliest trials would take nearly a half century to be discovered. This was first embodied in the device which came to be known as the video telephone, or videophone, and it evolved from intensive research and experimentation in several telecommunication fields, notably electrical telegraphy, telephony, radio, and television.

The development of the crucial video technology first started in the latter half of the 1920s in the United Kingdom and the United States, spurred notably by John Logie Baird and AT&T’s Bell Labs. This occurred in part, at least by AT&T, to serve as an adjunct supplementing the use of the telephone. A number of organizations believed that videotelephony would be superior to plain voice communications. However video technology was to be deployed in analog television broadcasting long before it could become practical—or popular—for videophones.

Videotelephony developed in parallel with conventional voice telephone systems from the mid-to-late 20th century. Only in the late 20th century with the advent of powerful video codecs and high-speed broadband did it become a practical technology for regular use. With the rapid improvements and popularity of the Internet, it became widespread through the use of videoconferencing and webcams, which frequently utilize Internet telephony, and in business, where telepresence technology has helped reduce the need to travel.

Practical digital videotelephony was only made possible with advances in video compression, due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed video. To achieve Video Graphics Array (VGA) quality video (480p resolution and 256 colors) with raw uncompressed video, it would require a bandwidth of over 92 Mbps.[40]

Satellite[edit]

The first U.S. satellite to relay communications was Project SCORE in 1958, which used a tape recorder to store and forward voice messages. It was used to send a Christmas greeting to the world from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1960 NASA launched an Echo satellite; the 100-foot (30 m) aluminized PET film balloon served as a passive reflector for radio communications. Courier 1B, built by Philco, also launched in 1960, was the world’s first active repeater satellite. Satellites these days are used for many applications such as GPS, television, internet and telephone.

Telstar was the first active, direct relay commercial communications satellite. Belonging to AT&T as part of a multi-national agreement between AT&T, Bell Telephone Laboratories, NASA, the British General Post Office, and the French National PTT (Post Office) to develop satellite communications, it was launched by NASA from Cape Canaveral on July 10, 1962, the first privately sponsored space launch. Relay 1 was launched on December 13, 1962, and became the first satellite to broadcast across the Pacific on November 22, 1963.[41]

The first and historically most important application for communication satellites was in intercontinental long-distance telephony. The fixed Public Switched Telephone Network relays telephone calls from land line telephones to an earth station, where they are then transmitted a receiving satellite dish via a geostationary satellite in Earth orbit. Improvements in submarine communications cables, through the use of fiber-optics, caused some decline in the use of satellites for fixed telephony in the late 20th century, but they still exclusively service remote islands such as Ascension Island, Saint Helena, Diego Garcia, and Easter Island, where no submarine cables are in service. There are also some continents and some regions of countries where landline telecommunications are rare to nonexistent, for example Antarctica, plus large regions of Australia, South America, Africa, Northern Canada, China, Russia and Greenland.

After commercial long-distance telephone service was established via communication satellites, a host of other commercial telecommunications were also adapted to similar satellites starting in 1979, including mobile satellite phones, satellite radio, satellite television and satellite Internet access. The earliest adaption for most such services occurred in the 1990s as the pricing for commercial satellite transponder channels continued to drop significantly.

Realization and demonstration, on October 29, 2001, of the first digital cinema transmission by satellite in Europe[42][43][44] of a feature film by Bernard Pauchon,[45] Alain Lorentz, Raymond Melwig[46] and Philippe Binant.[47]

Computer networks and the Internet[edit]

On September 11, 1940, George Stibitz was able to transmit problems using teletype to his Complex Number Calculator in New York City and receive the computed results back at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.[48] This configuration of a centralized computer or mainframe with remote dumb terminals remained popular throughout the 1950s. However it was not until the 1960s that researchers started to investigate packet switching a technology that would allow chunks of data to be sent to different computers without first passing through a centralized mainframe. A four-node network emerged on December 5, 1969 between the University of California, Los Angeles, the Stanford Research Institute, the University of Utah and the University of California, Santa Barbara. This network would become ARPANET, which by 1981 would consist of 213 nodes.[49] In June 1973, the first non-US node was added to the network belonging to Norway’s NORSAR project. This was shortly followed by a node in London.[50]

ARPANET’s development centred on the Request for Comments process and on April 7, 1969, RFC 1 was published. This process is important because ARPANET would eventually merge with other networks to form the Internet and many of the protocols the Internet relies upon today were specified through this process. The first Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) specification, RFC 675 (Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program), was written by Vinton Cerf, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine, and published in December 1974. It coined the term «Internet» as a shorthand for internetworking.[51] In September 1981, RFC 791 introduced the Internet Protocol v4 (IPv4). This established the TCP/IP protocol, which much of the Internet relies upon today. The User Datagram Protocol (UDP), a more relaxed transport protocol that, unlike TCP, did not guarantee the orderly delivery of packets, was submitted on 28 August 1980 as RFC 768. An e-mail protocol, SMTP, was introduced in August 1982 by RFC 821 and [[HTTP|http://1.0[permanent dead link]]] a protocol that would make the hyperlinked Internet possible was introduced in May 1996 by RFC 1945.

However, not all important developments were made through the Request for Comments process. Two popular link protocols for local area networks (LANs) also appeared in the 1970s. A patent for the Token Ring protocol was filed by Olof Söderblom on October 29, 1974.[52] And a paper on the Ethernet protocol was published by Robert Metcalfe and David Boggs in the July 1976 issue of Communications of the ACM.[53] The Ethernet protocol had been inspired by the ALOHAnet protocol which had been developed by electrical engineering researchers at the University of Hawaii.

Internet access became widespread late in the century, using the old telephone and television networks.

Digital telephone technology[edit]

MOS technology was initially overlooked by Bell because they did not find it practical for analog telephone applications.[54][55] MOS technology eventually became practical for telephone applications with the MOS mixed-signal integrated circuit, which combines analog and digital signal processing on a single chip, developed by former Bell engineer David A. Hodges with Paul R. Gray at UC Berkeley in the early 1970s.[55] In 1974, Hodges and Gray worked with R.E. Suarez to develop MOS switched capacitor (SC) circuit technology, which they used to develop the digital-to-analog converter (DAC) chip, using MOSFETs and MOS capacitors for data conversion. This was followed by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) chip, developed by Gray and J. McCreary in 1975.[55]

MOS SC circuits led to the development of PCM codec-filter chips in the late 1970s.[55][56] The silicon-gate CMOS (complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980,[55] has since been the industry standard for digital telephony.[55][56] By the 1990s, telecommunication networks such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN) had been largely digitized with very-large-scale integration (VLSI) CMOS PCM codec-filters, widely used in electronic switching systems for telephone exchanges and data transmission applications.[56]

Wireless revolution[edit]

The wireless revolution began in the 1990s,[57][58][59] with the advent of digital wireless networks leading to a social revolution, and a paradigm shift from wired to wireless technology,[60] including the proliferation of commercial wireless technologies such as cell phones, mobile telephony, pagers, wireless computer networks,[57] cellular networks, the wireless Internet, and laptop and handheld computers with wireless connections.[61] The wireless revolution has been driven by advances in radio frequency (RF) and microwave engineering,[57] and the transition from analog to digital RF technology.[60][61]

Advances in metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET, or MOS transistor) technology, the key component of the RF technology that enables digital wireless networks, has been central to this revolution.[60] Hitachi developed the vertical power MOSFET in 1969, but it was not until Ragle perfected the concept in 1976 that the power MOSFET became practical.[62] In 1977 Hitachi announce a planar type of DMOS that was practical for audio power output stages.[63] RF CMOS (radio frequency CMOS) integrated circuit technology was later developed by Asad Abidi at UCLA in the late 1980s.[64] By the 1990s, RF CMOS integrated circuits were widely adopted as RF circuits,[64] while discrete MOSFET (power MOSFET and LDMOS) devices were widely adopted as RF power amplifiers, which led to the development and proliferation of digital wireless networks.[60][65] Most of the essential elements of modern wireless networks are built from MOSFETs, including base station modules, routers,[65] telecommunication circuits,[66] and radio transceivers.[64] MOSFET scaling has led to rapidly increasing wireless bandwidth, which has been doubling every 18 months (as noted by Edholm’s law).[60]

Timeline[edit]

Visual, auditory and ancillary methods (non-electrical)[edit]

- Prehistoric: Fires, beacons, smoke signals, communication drums, horns

- 6th century BCE: Mail

- 5th century BCE: Pigeon post

- 4th century BCE: Hydraulic semaphores

- 15th century CE: Maritime flag semaphores

- 1672: First experimental acoustic (mechanical) telephone

- 1790: Semaphore lines (optical telegraphs)

- 1867: Signal lamps

- 1877: Acoustic phonograph

- 1900; optical

picture

Basic electrical signals[edit]

- 1838: Electrical telegraph. See: Telegraph history

- 1830s: Beginning of attempts to develop «wireless telegraphy», systems using some form of ground, water, air or other media for conduction to eliminate the need for conducting wires.

- 1858: First trans-Atlantic telegraph cable

- 1876: Telephone. See: Invention of the telephone, History of the telephone, Timeline of the telephone

- 1880: Telephony via lightbeam photophones

Advanced electrical and electronic signals[edit]

- 1896: First practical wireless telegraphy systems based on Radio. See: History of radio.

- 1900: first television displayed only black and white images. Over the next decades, colour television were invented, showing images that were clearer and in full colour.

- 1914: First North American transcontinental telephone calling

- 1927: Television. See: History of television

- 1927: First commercial radio-telephone service, U.K.–U.S.

- 1930: First experimental videophones

- 1934: First commercial radio-telephone service, U.S.–Japan

- 1936: World’s first public videophone network

- 1946: Limited capacity Mobile Telephone Service for automobiles

- 1947: First working transistor (see History of the transistor)

- 1950: Semiconductor era begins

- 1956: Transatlantic telephone cable

- 1962: Commercial telecommunications satellite

- 1964: Fiber optical telecommunications

- 1965: First North American public videophone network

- 1969: Computer networking

- 1973: First modern-era mobile (cellular) phone

- 1974: Internet (see History of Internet)

- 1979: INMARSAT ship-to-shore satellite communications

- 1981: First mobile (cellular) phone network

- 1982: SMTP email

- 1998: Mobile satellite hand-held phones

- 2003: VoIP Internet Telephony

See also[edit]

- History of the Internet

- History of radio

- History of television

- History of the telephone

- History of videotelephony

- Information Age

- Information revolution

- Optical communication

- Outline of telecommunication

References[edit]

- ^ Tomkins, William (2005). «Native American Smoke Signals».

- ^ «Talking Drums». Instrument Encyclopedia, Cultural Heritage for Community Outreach. 1996. Archived from the original on 2006-09-10.

- ^ Levi, Wendell (1977). The Pigeon. Sumter, S.C.: Levi Publishing Co, Inc. ISBN 0853900132.

- ^ Lahanas, Michael. «Ancient Greek Communication Methods». Mlahanas.de. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Ross, David (October 2008). «The Spanish Armada». Britain Express.

- ^ Aitken, Frédéric; Foulc, Jean-Numa (2019). «Chap. 1». From deep sea to laboratory. 1 : the first explorations of the deep sea by H.M.S. Challenger (1872-1876). London.: ISTE-WILEY. ISBN 9781786303745.

- ^ Wenzlhuemer (2013). Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World. pp. 63–64. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139177986. ISBN 9781139177986.

- ^ Chatenet, Cédrick (2003). «Les Télégraphes Chappe». l’Ecole Centrale de Lyon. Archived from the original on 2011-03-17.

- ^ «CCIT/ITU-T 50 Years of Excellence» (PDF). International Telecommunication Union. 2006.

- ^ a b Jones, R. Victor. «Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring’s «Space Multiplexed» Electrochemical Telegraph (1808-10)». Harvard. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

Semaphore to Satellite. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1965. - ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Calvert, J. B. (19 May 2004). «The Hindot Electromagnetic Telegraph». Archived from the original on 2007-08-04.

- ^ Calvert, J. B. (April 2000). «The Electromagnetic Telegraph». Archived from the original on 2007-08-04.

- ^ Wenzlhuemer (2013). Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World. p. 74. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139177986. ISBN 9781139177986.

- ^ Dibner, Bern (1959). «The Atlantic Cable». Burndy Library.

- ^ Brown, Travis (1994). Historical first patents: the first United States patent for many everyday things (illustrated ed.). University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press. pp. 179. ISBN 978-0-8108-2898-8.

- ^ «Connected Earth: The telephone». BT. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-08-22. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ «History of AT&T». 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Page, Arthur W. (January 1906). «Communication By Wire And ‘Wireless’: The Wonders of Telegraph and Telephone». The World’s Work: A History of Our Time. XIII: 8408–8422. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ «First Transatlantic Telephone Call», History, retrieved 2019-03-22

- ^ Glover, Bill (2006). «History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy».

- ^ Clarke, Arthur C. (1958). Voice Across the Sea. New York City: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 9780860020684.

- ^ Icons of invention: the makers of the modern world from Gutenberg to Gates. ABC-CLIO. 2009. ISBN 9780313347436. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Vujovic, Ljubo (1998). «Tesla Biography». Tesla Memorial Society of New York.

- ^ «Milestones: First Millimeter-wave Communication Experiments by J.C. Bose, 1894-96». List of IEEE milestones. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Emerson, D. T. (1997). «The work of Jagadis Chandra Bose: 100 years of MM-wave research». IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Research. 45 (12): 2267–2273. Bibcode:1997imsd.conf..553E. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602853. ISBN 9780986488511. S2CID 9039614.

- ^ «Timeline». The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ «1901: Semiconductor Rectifiers Patented as «Cat’s Whisker» Detectors». The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ a b «Milestones:Development of Electronic Television, 1924-1941». Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ «Kenjiro Takayanagi: The Father of Japanese Television». NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation). 2002. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ^ High Above: The untold story of Astra, Europe’s leading satellite company. Springer Science+Business Media. 28 August 2011. p. 220. ISBN 9783642120091.

- ^ Abramson, Albert (1995). Zworykin, Pioneer of Television. University of Illinois Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-252-02104-5.

- ^ a b «The Baird Television Website».

- ^ «The Pioneers». MZTV Museum of Television. 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-05-14.

- ^ Postman, Neil (29 March 1999). «Philo Farnsworth». Time. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14.

- ^ Karwatka, D (1996). «Philo Farnsworth—television pioneer». Tech Directions. 56 (4): 7.

- ^ Postman, Neil (29 March 1999). «Philo Farnsworth». Time. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14.

- ^ Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003). The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 363–8. ISBN 9780471205050.

- ^ Srivastava, Viranjay M.; Singh, Ghanshyam (2013). MOSFET Technologies for Double-Pole Four-Throw Radio-Frequency Switch. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9783319011653.

- ^ Belmudez, Benjamin (2014). Audiovisual Quality Assessment and Prediction for Videotelephony. Springer. pp. 11–13. ISBN 9783319141664.

- ^ «Significant Achievements in Space Communications and Navigation, 1958-1964» (PDF). NASA-SP-93. NASA. 1966. pp. 30–32. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ^ France Télécom, Commission Supérieure Technique de l’Image et du Son, Communiqué de presse, Paris, October 29th, 2001.

- ^ ««Numérique : le cinéma en mutation», Projections, 13, CNC, Paris, September 2004, p. 7″ (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ Bomsel, Olivier; Le Blanc, Gilles (2002). Dernier tango argentique. Le cinéma face à la numérisation. Ecole des Mines de Paris. p. 12. ISBN 9782911762420.

- ^ Pauchon, Bernard (2001). «France Telecom and digital cinema». ShowEast. p. 10.

- ^ Georgescu, Alexandru (2019). Critical Space Infrastructures. Risk, Resilience and Complexity. Springer. p. 48. ISBN 9783030126049.

- ^ «Première numérique pour le cinéma français». 01net. 2002. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ «George Stibitz». Kerry Redshaw. 1996.

- ^ Hafner, Katie (1998). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83267-4.

- ^ «NORSAR and the Internet: Together since 1973». NORSAR. 2006. Archived from the original on 2005-09-10.

- ^ Cerf, Vint (December 1974). Specification of Internet Transmission Control Protocol. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0675. RFC 675.

- ^ USA 4293948, Olof Soderblom, «Data transmission system», issued October 6, 1981

- ^ Metcalfe, Robert M.; Boggs, David R. (July 1976). «Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks». Communications of the ACM. 19 (5): 395–404. doi:10.1145/360248.360253. S2CID 429216.

- ^ Maloberti, Franco; Davies, Anthony C. (2016). «History of Electronic Devices» (PDF). A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing. IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. pp. 59-70 (65-7). ISBN 9788793609860. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Allstot, David J. (2016). «Switched Capacitor Filters» (PDF). In Maloberti, Franco; Davies, Anthony C. (eds.). A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing. IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. pp. 105–110. ISBN 9788793609860. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b c Floyd, Michael D.; Hillman, Garth D. (8 October 2018) [1st pub. 2000]. «Pulse-Code Modulation Codec-Filters». The Communications Handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 26–1, 26–2, 26–3. ISBN 9781420041163.

- ^ a b c Golio, Mike; Golio, Janet (2018). RF and Microwave Passive and Active Technologies. CRC Press. pp. ix, I–1. ISBN 9781420006728.

- ^ Rappaport, T. S. (November 1991). «The wireless revolution». IEEE Communications Magazine. 29 (11): 52–71. doi:10.1109/35.109666. S2CID 46573735.

- ^ «The wireless revolution». The Economist. January 21, 1999. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Baliga, B. Jayant (2005). Silicon RF Power MOSFETS. World Scientific. ISBN 9789812561213.

- ^ a b Harvey, Fiona (May 8, 2003). «The Wireless Revolution». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Oxner, E. S. (1988). Fet Technology and Application. CRC Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780824780500.

- ^ Duncan, Ben (1996). High Performance Audio Power Amplifiers. Elsevier. pp. 177–8, 406. ISBN 9780080508047.

- ^ a b c O’Neill, A. (2008). «Asad Abidi Recognized for Work in RF-CMOS». IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter. 13 (1): 57–58. doi:10.1109/N-SSC.2008.4785694. ISSN 1098-4232.

- ^ a b Asif, Saad (2018). 5G Mobile Communications: Concepts and Technologies. CRC Press. pp. 128–134. ISBN 9780429881343.

- ^ Colinge, Jean-Pierre; Greer, James C. (2016). Nanowire Transistors: Physics of Devices and Materials in One Dimension. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781107052406.

Sources[edit]

- Wenzlhuemer, Roland. Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World: The Telegraph and Globalization. Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 9781107025288

Further reading[edit]

- Hilmes, Michele. Network Nations: A Transnational History of American and British Broadcasting (2011)

- John, Richard. Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Harvard U.P. 2010), emphasis on telephone

- Noll, Michael. The Evolution of Media, 2007, Rowman & Littlefield

- Poe, Marshall T. A History of Communications: Media and Society From the Evolution of Speech to the Internet (Cambridge University Press; 2011) 352 pages; Documents how successive forms of communication are embraced and, in turn, foment change in social institutions.

- Wheen, Andrew. DOT-DASH TO DOT.COM: How Modern Telecommunications Evolved from the Telegraph to the Internet (Springer, 2011)

- Wu, Tim. The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires (2010)

- Lundy, Bert. Telegraph, Telephone and Wireless: How Telecom Changed the World (2008)

External links[edit]

- Katz, Randy H., «History of Communications Infrastructures» Archived 2011-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department (EECS) Department, University of California, Berkeley.

- International Telecommunication Union

- Aronsson’s Telecom History Timeline

- From the Thurn & Taxis to the Phone Book of the World — 730 years of Telecom History

- Telecommunications History Group Virtual Museum

- Telecommunications History Germany

- Telecommunications History France

The history of telecommunication began with the use of smoke signals and drums in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. In the 1790s, the first fixed semaphore systems emerged in Europe. However, it was not until the 1830s that electrical telecommunication systems started to appear. This article details the history of telecommunication and the individuals who helped make telecommunication systems what they are today. The history of telecommunication is an important part of the larger history of communication.

Ancient systems and optical telegraphy[edit]

Early telecommunications included smoke signals and drums. Talking drums were used by natives in Africa, and smoke signals in North America and China. These systems were often used to do more than announce the presence of a military camp.[1][2]

In Rabbinical Judaism a signal was given by means of kerchiefs or flags at intervals along the way back to the high priest to indicate the goat «for Azazel» had been pushed from the cliff.

Homing pigeons have occasionally been used throughout history by different cultures. Pigeon post had Persian roots, and was later used by the Romans to aid their military.[3]

Greek hydraulic semaphore systems were used as early as the 4th century BC. The hydraulic semaphores, which worked with water filled vessels and visual signals, functioned as optical telegraphs. However, they could only utilize a very limited range of pre-determined messages, and as with all such optical telegraphs could only be deployed during good visibility conditions.[4]

Code of letters and symbols for Chappe telegraph (Rees’s Cyclopaedia)

During the Middle Ages, chains of beacons were commonly used on hilltops as a means of relaying a signal. Beacon chains suffered the drawback that they could only pass a single bit of information, so the meaning of the message such as «the enemy has been sighted» had to be agreed upon in advance. One notable instance of their use was during the Spanish Armada, when a beacon chain relayed a signal from Plymouth to London that signaled the arrival of the Spanish warships.[5]

In 1774, the Swiss physicist Georges Lesage built an electrostatic telegraph consisting of a set of 24 conductive wires a few meters long connected to 24 elder balls suspended from a silk thread (each wire corresponds to a letter). The electrification of a wire by means of an electrostatic generator causes the corresponding elder ball to deflect and designate a letter to the operator located at the end of the line. The sequence of selected letters leads to the writing and transmission of a message.[6]

French engineer Claude Chappe began working on visual telegraphy in 1790, using pairs of «clocks» whose hands pointed at different symbols. These did not prove quite viable at long distances, and Chappe revised his model to use two sets of jointed wooden beams. Operators moved the beams using cranks and wires.[7] He built his first telegraph line between Lille and Paris, followed by a line from Strasbourg to Paris. In 1794, a Swedish engineer, Abraham Edelcrantz built a quite different system from Stockholm to Drottningholm. As opposed to Chappe’s system which involved pulleys rotating beams of wood, Edelcrantz’s system relied only upon shutters and was therefore faster.[8]

However, semaphore as a communication system suffered from the need for skilled operators and expensive towers often at intervals of only ten to thirty kilometers (six to nineteen miles). As a result, the last commercial line was abandoned in 1880.[9]

Electrical telegraph[edit]

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including Laplace, Ampère, and Gauss were involved.

An early experiment in electrical telegraphy was an ‘electrochemical’ telegraph created by the German physician, anatomist and inventor Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring in 1809, based on an earlier, less robust design of 1804 by Spanish polymath and scientist Francisco Salva Campillo.[10] Both their designs employed multiple wires (up to 35) in order to visually represent almost all Latin letters and numerals. Thus, messages could be conveyed electrically up to a few kilometers (in von Sömmerring’s design), with each of the telegraph receiver’s wires immersed in a separate glass tube of acid. An electric current was sequentially applied by the sender through the various wires representing each digit of a message; at the recipient’s end the currents electrolysed the acid in the tubes in sequence, releasing streams of hydrogen bubbles next to each associated letter or numeral. The telegraph receiver’s operator would visually observe the bubbles and could then record the transmitted message, albeit at a very low baud rate.[10] The principal disadvantage to the system was its prohibitive cost, due to having to manufacture and string-up the multiple wire circuits it employed, as opposed to the single wire (with ground return) used by later telegraphs.

The first working telegraph was built by Francis Ronalds in 1816 and used static electricity.[11]

Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke patented a five-needle, six-wire system, which entered commercial use in 1838.[12] It used the deflection of needles to represent messages and started operating over twenty-one kilometres (thirteen miles) of the Great Western Railway on 9 April 1839. Both Wheatstone and Cooke viewed their device as «an improvement to the [existing] electromagnetic telegraph» not as a new device.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Samuel Morse developed a version of the electrical telegraph which he demonstrated on 2 September 1837. Alfred Vail saw this demonstration and joined Morse to develop the register—a telegraph terminal that integrated a logging device for recording messages to paper tape. This was demonstrated successfully over three miles (five kilometres) on 6 January 1838 and eventually over forty miles (sixty-four kilometres) between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore on 24 May 1844. The patented invention proved lucrative and by 1851 telegraph lines in the United States spanned over 20,000 miles (32,000 kilometres).[13] Morse’s most important technical contribution to this telegraph was the simple and highly efficient Morse Code, co-developed with Vail, which was an important advance over Wheatstone’s more complicated and expensive system, and required just two wires. The communications efficiency of the Morse Code preceded that of the Huffman code in digital communications by over 100 years, but Morse and Vail developed the code purely empirically, with shorter codes for more frequent letters.

The submarine cable across the English Channel, wire coated in gutta percha, was laid in 1851.[14] Transatlantic cables installed in 1857 and 1858 only operated for a few days or weeks (carried messages of greeting back and forth between James Buchanan and Queen Victoria) before they failed.[15] The project to lay a replacement line was delayed for five years by the American Civil War. The first successful transatlantic telegraph cable was completed on 27 July 1866, allowing continuous transatlantic telecommunication for the first time.

Telephone[edit]

The master telephone patent, 174465, granted to Bell, March 7, 1876

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of New Haven, Connecticut in the US and London, England in the UK. Alexander Graham Bell held the master patent for the telephone that was needed for such services in both countries.[16] All other patents for electric telephone devices and features flowed from this master patent. Credit for the invention of the electric telephone has been frequently disputed, and new controversies over the issue have arisen from time-to-time. As with other great inventions such as radio, television, the light bulb, and the digital computer, there were several inventors who did pioneering experimental work on voice transmission over a wire, who then improved on each other’s ideas. However, the key innovators were Alexander Graham Bell and Gardiner Greene Hubbard, who created the first telephone company, the Bell Telephone Company in the United States, which later evolved into American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), at times the world’s largest phone company.

Telephone technology grew quickly after the first commercial services emerged, with inter-city lines being built and telephone exchanges in every major city of the United States by the mid-1880s.[17][18][19] The first transcontinental telephone call occurred on January 25, 1915. Despite this, transatlantic voice communication remained impossible for customers until January 7, 1927 when a connection was established using radio.[20] However no cable connection existed until TAT-1 was inaugurated on September 25, 1956 providing 36 telephone circuits.[21]

In 1880, Bell and co-inventor Charles Sumner Tainter conducted the world’s first wireless telephone call via modulated lightbeams projected by photophones. The scientific principles of their invention would not be utilized for several decades, when they were first deployed in military and fiber-optic communications.

The first transatlantic telephone cable (which incorporated hundreds of electronic amplifiers) was not operational until 1956, only six years before the first commercial telecommunications satellite, Telstar, was launched into space.[22]

Radio and television[edit]

Over several years starting in 1894, the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi worked on adapting the newly discovered phenomenon of radio waves to telecommunication, building the first wireless telegraphy system using them.[23] In December 1901, he established wireless communication between St. John’s, Newfoundland and Poldhu, Cornwall (England), earning him a Nobel Prize in Physics (which he shared with Karl Braun) in 1909.[24] In 1900, Reginald Fessenden was able to wirelessly transmit a human voice.

Millimetre wave communication was first investigated by Bengali physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose during 1894–1896, when he reached an extremely high frequency of up to 60 GHz in his experiments.[25] He also introduced the use of semiconductor junctions to detect radio waves,[26] when he patented the radio crystal detector in 1901.[27][28]

In 1924, Japanese engineer Kenjiro Takayanagi began a research program on electronic television. In 1925, he demonstrated a CRT television with thermal electron emission.[29] In 1926, he demonstrated a CRT television with 40-line resolution,[30] the first working example of a fully electronic television receiver.[29] In 1927, he increased the television resolution to 100 lines, which was unrivaled until 1931.[31] In 1928, he was the first to transmit human faces in half-tones on television, influencing the later work of Vladimir K. Zworykin.[32]

On March 25, 1925, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird publicly demonstrated the transmission of moving silhouette pictures at the London department store Selfridge’s. Baird’s system relied upon the fast-rotating Nipkow disk, and thus it became known as the mechanical television. In October 1925, Baird was successful in obtaining moving pictures with halftone shades, which were by most accounts the first true television pictures.[33] This led to a public demonstration of the improved device on 26 January 1926 again at Selfridges. His invention formed the basis of semi-experimental broadcasts done by the British Broadcasting Corporation beginning September 30, 1929.[34]

For most of the twentieth century televisions used the cathode ray tube (CRT) invented by Karl Braun. Such a television was produced by Philo Farnsworth, who demonstrated crude silhouette images to his family in Idaho on September 7, 1927.[35] Farnsworth’s device would compete with the concurrent work of Kalman Tihanyi and Vladimir Zworykin. Though the execution of the device was not yet what everyone hoped it could be, it earned Farnsworth a small production company. In 1934, he gave the first public demonstration of the television at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute and opened his own broadcasting station.[36] Zworykin’s camera, based on Tihanyi’s Radioskop, which later would be known as the Iconoscope, had the backing of the influential Radio Corporation of America (RCA). In the United States, court action between Farnsworth and RCA would resolve in Farnsworth’s favour.[37] John Logie Baird switched from mechanical television and became a pioneer of colour television using cathode-ray tubes.[33]

After mid-century the spread of coaxial cable and microwave radio relay allowed television networks to spread across even large countries.

Semiconductor era[edit]

The modern period of telecommunication history from 1950 onwards is referred to as the semiconductor era, due to the wide adoption of semiconductor devices in telecommunication technology. The development of transistor technology and the semiconductor industry enabled significant advances in telecommunication technology, led to the price of telecommunications services declining significantly, and led to a transition away from state-owned narrowband circuit-switched networks to private broadband packet-switched networks. In turn, this led to a significant increase in the total number of telephone subscribers, reaching nearly 1 billion users worldwide by the end of the 20th century.[38]

The development of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) large-scale integration (LSI) technology, information theory and cellular networking led to the development of affordable mobile communications. There was a rapid growth of the telecommunications industry towards the end of the 20th century, primarily due to the introduction of digital signal processing in wireless communications, driven by the development of low-cost, very large-scale integration (VLSI) RF CMOS (radio-frequency complementary MOS) technology.[39]

Videotelephony[edit]

The 1969 AT&T Mod II Picturephone, the result of decades long R&D at a cost of over $500M.

The development of videotelephony involved the historical development of several technologies which enabled the use of live video in addition to voice telecommunications. The concept of videotelephony was first popularized in the late 1870s in both the United States and Europe, although the basic sciences to permit its very earliest trials would take nearly a half century to be discovered. This was first embodied in the device which came to be known as the video telephone, or videophone, and it evolved from intensive research and experimentation in several telecommunication fields, notably electrical telegraphy, telephony, radio, and television.

The development of the crucial video technology first started in the latter half of the 1920s in the United Kingdom and the United States, spurred notably by John Logie Baird and AT&T’s Bell Labs. This occurred in part, at least by AT&T, to serve as an adjunct supplementing the use of the telephone. A number of organizations believed that videotelephony would be superior to plain voice communications. However video technology was to be deployed in analog television broadcasting long before it could become practical—or popular—for videophones.

Videotelephony developed in parallel with conventional voice telephone systems from the mid-to-late 20th century. Only in the late 20th century with the advent of powerful video codecs and high-speed broadband did it become a practical technology for regular use. With the rapid improvements and popularity of the Internet, it became widespread through the use of videoconferencing and webcams, which frequently utilize Internet telephony, and in business, where telepresence technology has helped reduce the need to travel.

Practical digital videotelephony was only made possible with advances in video compression, due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed video. To achieve Video Graphics Array (VGA) quality video (480p resolution and 256 colors) with raw uncompressed video, it would require a bandwidth of over 92 Mbps.[40]

Satellite[edit]

The first U.S. satellite to relay communications was Project SCORE in 1958, which used a tape recorder to store and forward voice messages. It was used to send a Christmas greeting to the world from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1960 NASA launched an Echo satellite; the 100-foot (30 m) aluminized PET film balloon served as a passive reflector for radio communications. Courier 1B, built by Philco, also launched in 1960, was the world’s first active repeater satellite. Satellites these days are used for many applications such as GPS, television, internet and telephone.

Telstar was the first active, direct relay commercial communications satellite. Belonging to AT&T as part of a multi-national agreement between AT&T, Bell Telephone Laboratories, NASA, the British General Post Office, and the French National PTT (Post Office) to develop satellite communications, it was launched by NASA from Cape Canaveral on July 10, 1962, the first privately sponsored space launch. Relay 1 was launched on December 13, 1962, and became the first satellite to broadcast across the Pacific on November 22, 1963.[41]

The first and historically most important application for communication satellites was in intercontinental long-distance telephony. The fixed Public Switched Telephone Network relays telephone calls from land line telephones to an earth station, where they are then transmitted a receiving satellite dish via a geostationary satellite in Earth orbit. Improvements in submarine communications cables, through the use of fiber-optics, caused some decline in the use of satellites for fixed telephony in the late 20th century, but they still exclusively service remote islands such as Ascension Island, Saint Helena, Diego Garcia, and Easter Island, where no submarine cables are in service. There are also some continents and some regions of countries where landline telecommunications are rare to nonexistent, for example Antarctica, plus large regions of Australia, South America, Africa, Northern Canada, China, Russia and Greenland.

After commercial long-distance telephone service was established via communication satellites, a host of other commercial telecommunications were also adapted to similar satellites starting in 1979, including mobile satellite phones, satellite radio, satellite television and satellite Internet access. The earliest adaption for most such services occurred in the 1990s as the pricing for commercial satellite transponder channels continued to drop significantly.

Realization and demonstration, on October 29, 2001, of the first digital cinema transmission by satellite in Europe[42][43][44] of a feature film by Bernard Pauchon,[45] Alain Lorentz, Raymond Melwig[46] and Philippe Binant.[47]

Computer networks and the Internet[edit]

On September 11, 1940, George Stibitz was able to transmit problems using teletype to his Complex Number Calculator in New York City and receive the computed results back at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.[48] This configuration of a centralized computer or mainframe with remote dumb terminals remained popular throughout the 1950s. However it was not until the 1960s that researchers started to investigate packet switching a technology that would allow chunks of data to be sent to different computers without first passing through a centralized mainframe. A four-node network emerged on December 5, 1969 between the University of California, Los Angeles, the Stanford Research Institute, the University of Utah and the University of California, Santa Barbara. This network would become ARPANET, which by 1981 would consist of 213 nodes.[49] In June 1973, the first non-US node was added to the network belonging to Norway’s NORSAR project. This was shortly followed by a node in London.[50]

ARPANET’s development centred on the Request for Comments process and on April 7, 1969, RFC 1 was published. This process is important because ARPANET would eventually merge with other networks to form the Internet and many of the protocols the Internet relies upon today were specified through this process. The first Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) specification, RFC 675 (Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program), was written by Vinton Cerf, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine, and published in December 1974. It coined the term «Internet» as a shorthand for internetworking.[51] In September 1981, RFC 791 introduced the Internet Protocol v4 (IPv4). This established the TCP/IP protocol, which much of the Internet relies upon today. The User Datagram Protocol (UDP), a more relaxed transport protocol that, unlike TCP, did not guarantee the orderly delivery of packets, was submitted on 28 August 1980 as RFC 768. An e-mail protocol, SMTP, was introduced in August 1982 by RFC 821 and [[HTTP|http://1.0[permanent dead link]]] a protocol that would make the hyperlinked Internet possible was introduced in May 1996 by RFC 1945.

However, not all important developments were made through the Request for Comments process. Two popular link protocols for local area networks (LANs) also appeared in the 1970s. A patent for the Token Ring protocol was filed by Olof Söderblom on October 29, 1974.[52] And a paper on the Ethernet protocol was published by Robert Metcalfe and David Boggs in the July 1976 issue of Communications of the ACM.[53] The Ethernet protocol had been inspired by the ALOHAnet protocol which had been developed by electrical engineering researchers at the University of Hawaii.

Internet access became widespread late in the century, using the old telephone and television networks.

Digital telephone technology[edit]

MOS technology was initially overlooked by Bell because they did not find it practical for analog telephone applications.[54][55] MOS technology eventually became practical for telephone applications with the MOS mixed-signal integrated circuit, which combines analog and digital signal processing on a single chip, developed by former Bell engineer David A. Hodges with Paul R. Gray at UC Berkeley in the early 1970s.[55] In 1974, Hodges and Gray worked with R.E. Suarez to develop MOS switched capacitor (SC) circuit technology, which they used to develop the digital-to-analog converter (DAC) chip, using MOSFETs and MOS capacitors for data conversion. This was followed by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) chip, developed by Gray and J. McCreary in 1975.[55]

MOS SC circuits led to the development of PCM codec-filter chips in the late 1970s.[55][56] The silicon-gate CMOS (complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980,[55] has since been the industry standard for digital telephony.[55][56] By the 1990s, telecommunication networks such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN) had been largely digitized with very-large-scale integration (VLSI) CMOS PCM codec-filters, widely used in electronic switching systems for telephone exchanges and data transmission applications.[56]

Wireless revolution[edit]

The wireless revolution began in the 1990s,[57][58][59] with the advent of digital wireless networks leading to a social revolution, and a paradigm shift from wired to wireless technology,[60] including the proliferation of commercial wireless technologies such as cell phones, mobile telephony, pagers, wireless computer networks,[57] cellular networks, the wireless Internet, and laptop and handheld computers with wireless connections.[61] The wireless revolution has been driven by advances in radio frequency (RF) and microwave engineering,[57] and the transition from analog to digital RF technology.[60][61]