Графическим отображением периодического закона является Периодическая система химических элементов. Известно более (700) форм периодической таблицы. Официальным по решению Международного союза химиков является её полудлинный вариант.

Рис. (1). Периодическая система химических элементов

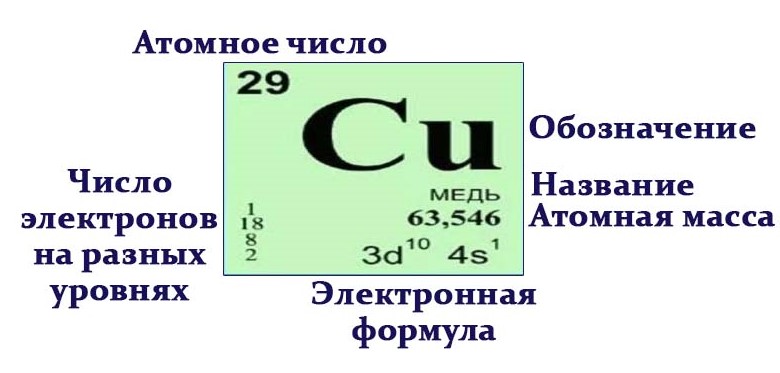

Каждому химическому элементу в таблице отведена одна клеточка, в которой указаны символ и название элемента, порядковый номер и относительная атомная масса.

Ломаная линия обозначает границу между металлами и неметаллами.

Последовательность расположения элементов не всегда совпадает с возрастанием атомной массы. Есть несколько исключений из правила. Так, относительная атомная масса аргона больше атомной массы калия, в теллура — больше, чем йода.

Каждый элемент имеет свой порядковый (атомный) номер, располагается в определённом периоде и определённой группе.

Период — горизонтальный ряд химических элементов, начинающийся щелочным металлом (или водородом) и заканчивающийся инертным (благородным) газом.

В таблице семь периодов. В каждом содержится определённое число элементов:

(1)-й период — (2) элемента,

(2)-й период — (8) элементов,

(3)-й период — (8) элементов,

(4)-й период — (18) элементов,

(5)-й период — (18) элементов,

(6)-й период — (32) элемента ((18 + 14)),

(7)-й период — (32) элемента ((18 + 14)).

Три первых периода называют малыми периодами, остальные — большими. И в малых, и в больших периодах происходит постепенное ослабление металлических свойств и усиление неметаллических, только в больших периодах оно происходит более плавно.

Элементы с порядковыми номерами (58)–(71) (лантаноиды) и (90)–(103) (актиноиды) вынесены из таблицы и располагаются под ней. Это элементы

IIIB

группы. Лантаноиды относятся к шестому периоду, а актиноиды — к седьмому.

Восьмой период появится в Периодической таблице, когда будут открыты новые элементы.

Группа — вертикальный столбец химических элементов, имеющих сходные свойства.

В Периодической таблице (18) групп, пронумерованных арабскими цифрами. Часто используют нумерацию римскими цифрами с добавлением букв (A) или (B). В таком случае групп (8).

Группы (A) начинаются элементами малых периодов, включают также и элементы больших периодов; содержат и металлы, и неметаллы. В коротком варианте Периодической таблицы это главные подгруппы.

Группы (B) содержат элементы больших периодов, и это только металлы. В коротком варианте Периодической таблицы это побочные подгруппы.

Число элементов в группах:

IA,

VIIIA

— по (7) элементов;

IIA —

VIIA

— по (6) элементов;

— (32) элемента ((4 + 14) лантаноидов (+ 14) актиноидов);

VIIIB — (12) элементов;

IB,

IIB

,

IVB

—

VIIB

— по (4) элемента.

Количественный состав групп будет изменяться по мере добавления в таблицу новых элементов.

Римский номер группы, как правило, показывает высшую валентность в оксидах. Но для некоторых элементов это правило не выполняется. Так, фтор не бывает семивалентным, а кислород — шестивалентным. Не проявляют валентность, равную номеру группы, гелий, неон и аргон — эти элементы не образуют соединений с кислородом. Медь бывает двухвалентной, а золото — трёхвалентным, хотя это элементы первой группы.

Некоторые группы (A) получили особые названия:

— щелочные металлы (

Li

,

Na

,

K

,

Rb

,

Cs

,

Fr

);

(кроме бериллия и магния) — щелочноземельные металлы (

Ca

,

Sr

,

Ba

,

Ra

);

— галогены (

F

,

Cl

,

Br

,

I

,

At

);

— благородные, или инертные, газы (

He

,

Ne

,

Ar

,

Kr

,

Xe

,

Rn

,

Og

).

Источники:

Рис. 1. Периодическая система химических элементов © ЯКласс

This article is about the mathematical concept. For number words denoting a position in a sequence («first», «second», «third», etc.), see Ordinal numeral.

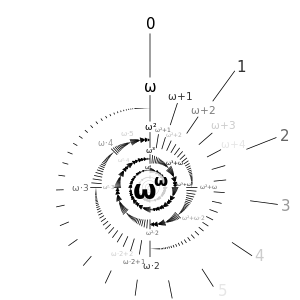

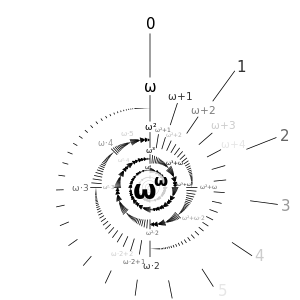

Representation of the ordinal numbers up to ωω. Each turn of the spiral represents one power of ω.

In set theory, an ordinal number, or ordinal, is a generalization of ordinal numerals (first, second, nth, etc.) aimed to extend enumeration to infinite sets.[1]

A finite set can be enumerated by successively labeling each element with the least natural number that has not been previously used. To extend this process to various infinite sets, ordinal numbers are defined more generally as linearly ordered labels that include the natural numbers and have the property that every set of ordinals has a least element (this is needed for giving a meaning to «the least unused element»).[2] This more general definition allows us to define an ordinal number

A linear order such that every subset has a least element is called a well-order. The axiom of choice implies that every set can be well-ordered, and given two well-ordered sets, one is isomorphic to an initial segment of the other. So ordinal numbers exist and are essentially unique.

Ordinal numbers are distinct from cardinal numbers, which measure the size of sets. Although the distinction between ordinals and cardinals is not always apparent on finite sets (one can go from one to the other just by counting labels), they are very different in the infinite case, where different infinite ordinals can correspond to sets having the same cardinal. Like other kinds of numbers, ordinals can be added, multiplied, and exponentiated, although none of these operations are commutative.

Ordinals were introduced by Georg Cantor in 1883[3] in order to accommodate infinite sequences and classify derived sets, which he had previously introduced in 1872 while studying the uniqueness of trigonometric series.[4]

Ordinals extend the natural numbers[edit]

A natural number (which, in this context, includes the number 0) can be used for two purposes: to describe the size of a set, or to describe the position of an element in a sequence. When restricted to finite sets, these two concepts coincide, since all linear orders of a finite set are isomorphic.

When dealing with infinite sets, however, one has to distinguish between the notion of size, which leads to cardinal numbers, and the notion of position, which leads to the ordinal numbers described here. This is because while any set has only one size (its cardinality), there are many nonisomorphic well-orderings of any infinite set, as explained below.

Whereas the notion of cardinal number is associated with a set with no particular structure on it, the ordinals are intimately linked with the special kind of sets that are called well-ordered. A well-ordered set is a totally ordered set in which every non-empty subset has a least element (a totally ordered set is an ordered set such that, given two distinct elements, one is less than the other). Equivalently, assuming the axiom of dependent choice, it is a totally ordered set without any infinite decreasing sequence — though there may be infinite increasing sequences. Ordinals may be used to label the elements of any given well-ordered set (the smallest element being labelled 0, the one after that 1, the next one 2, «and so on»), and to measure the «length» of the whole set by the least ordinal that is not a label for an element of the set. This «length» is called the order type of the set.

Any ordinal is defined by the set of ordinals that precede it. In fact, the most common definition of ordinals identifies each ordinal as the set of ordinals that precede it. For example, the ordinal 42 is generally identified as the set {0, 1, 2, …, 41}. Conversely, any set S of ordinals that is downward closed — meaning that for any ordinal α in S and any ordinal β < α, β is also in S — is (or can be identified with) an ordinal.

This definition of ordinals in terms of sets allows for infinite ordinals. The smallest infinite ordinal is

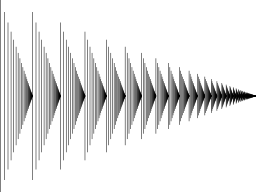

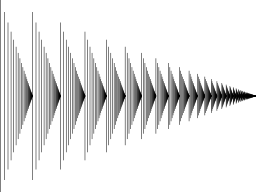

A graphical «matchstick» representation of the ordinal ω². Each stick corresponds to an ordinal of the form ω·m+n where m and n are natural numbers.

Perhaps a clearer intuition of ordinals can be formed by examining a first few of them: as mentioned above, they start with the natural numbers, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, … After all natural numbers comes the first infinite ordinal, ω, and after that come ω+1, ω+2, ω+3, and so on. (Exactly what addition means will be defined later on: just consider them as names.) After all of these come ω·2 (which is ω+ω), ω·2+1, ω·2+2, and so on, then ω·3, and then later on ω·4. Now the set of ordinals formed in this way (the ω·m+n, where m and n are natural numbers) must itself have an ordinal associated with it: and that is ω2. Further on, there will be ω3, then ω4, and so on, and ωω, then ωωω, then later ωωωω, and even later ε0 (epsilon nought) (to give a few examples of relatively small—countable—ordinals). This can be continued indefinitely (as every time one says «and so on» when enumerating ordinals, it defines a larger ordinal). The smallest uncountable ordinal is the set of all countable ordinals, expressed as ω1 or

Definitions[edit]

Well-ordered sets[edit]

In a well-ordered set, every non-empty subset contains a distinct smallest element. Given the axiom of dependent choice, this is equivalent to saying that the set is totally ordered and there is no infinite decreasing sequence (the latter being easier to visualize). In practice, the importance of well-ordering is justified by the possibility of applying transfinite induction, which says, essentially, that any property that passes on from the predecessors of an element to that element itself must be true of all elements (of the given well-ordered set). If the states of a computation (computer program or game) can be well-ordered—in such a way that each step is followed by a «lower» step—then the computation will terminate.

It is inappropriate to distinguish between two well-ordered sets if they only differ in the «labeling of their elements», or more formally: if the elements of the first set can be paired off with the elements of the second set such that if one element is smaller than another in the first set, then the partner of the first element is smaller than the partner of the second element in the second set, and vice versa. Such a one-to-one correspondence is called an order isomorphism, and the two well-ordered sets are said to be order-isomorphic or similar (with the understanding that this is an equivalence relation).

Formally, if a partial order ≤ is defined on the set S, and a partial order ≤’ is defined on the set S’ , then the posets (S,≤) and (S’ ,≤’) are order isomorphic if there is a bijection f that preserves the ordering. That is, f(a) ≤’ f(b) if and only if a ≤ b. Provided there exists an order isomorphism between two well-ordered sets, the order isomorphism is unique: this makes it quite justifiable to consider the two sets as essentially identical, and to seek a «canonical» representative of the isomorphism type (class). This is exactly what the ordinals provide, and it also provides a canonical labeling of the elements of any well-ordered set. Every well-ordered set (S,<) is order-isomorphic to the set of ordinals less than one specific ordinal number under their natural ordering. This canonical set is the order type of (S,<).

Essentially, an ordinal is intended to be defined as an isomorphism class of well-ordered sets: that is, as an equivalence class for the equivalence relation of «being order-isomorphic». There is a technical difficulty involved, however, in the fact that the equivalence class is too large to be a set in the usual Zermelo–Fraenkel (ZF) formalization of set theory. But this is not a serious difficulty. The ordinal can be said to be the order type of any set in the class.

Definition of an ordinal as an equivalence class[edit]

The original definition of ordinal numbers, found for example in the Principia Mathematica, defines the order type of a well-ordering as the set of all well-orderings similar (order-isomorphic) to that well-ordering: in other words, an ordinal number is genuinely an equivalence class of well-ordered sets. This definition must be abandoned in ZF and related systems of axiomatic set theory because these equivalence classes are too large to form a set. However, this definition still can be used in type theory and in Quine’s axiomatic set theory New Foundations and related systems (where it affords a rather surprising alternative solution to the Burali-Forti paradox of the largest ordinal).

Von Neumann definition of ordinals[edit]

| 0 | = | {} | = | ∅ |

| 1 | = | {0} | = | {∅} |

| 2 | = | {0,1} | = | {∅,{∅}} |

| 3 | = | {0,1,2} | = | {∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}}} |

| 4 | = | {0,1,2,3} | = | {∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}},{∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}}}} |

Rather than defining an ordinal as an equivalence class of well-ordered sets, it will be defined as a particular well-ordered set that (canonically) represents the class. Thus, an ordinal number will be a well-ordered set; and every well-ordered set will be order-isomorphic to exactly one ordinal number.

For each well-ordered set

- A set S is an ordinal if and only if S is strictly well-ordered with respect to set membership and every element of S is also a subset of S.

The natural numbers are thus ordinals by this definition. For instance, 2 is an element of 4 = {0, 1, 2, 3}, and 2 is equal to {0, 1} and so it is a subset of {0, 1, 2, 3}.

It can be shown by transfinite induction that every well-ordered set is order-isomorphic to exactly one of these ordinals, that is, there is an order preserving bijective function between them.

Furthermore, the elements of every ordinal are ordinals themselves. Given two ordinals S and T, S is an element of T if and only if S is a proper subset of T. Moreover, either S is an element of T, or T is an element of S, or they are equal. So every set of ordinals is totally ordered. Further, every set of ordinals is well-ordered. This generalizes the fact that every set of natural numbers is well-ordered.

Consequently, every ordinal S is a set having as elements precisely the ordinals smaller than S. For example, every set of ordinals has a supremum, the ordinal obtained by taking the union of all the ordinals in the set. This union exists regardless of the set’s size, by the axiom of union.

The class of all ordinals is not a set. If it were a set, one could show that it was an ordinal and thus a member of itself, which would contradict its strict ordering by membership. This is the Burali-Forti paradox. The class of all ordinals is variously called «Ord», «ON», or «∞».

An ordinal is finite if and only if the opposite order is also well-ordered, which is the case if and only if each of its non-empty subsets has a maximum.

Other definitions[edit]

There are other modern formulations of the definition of ordinal. For example, assuming the axiom of regularity, the following are equivalent for a set x:

- x is a (von Neumann) ordinal,

- x is a transitive set, and set membership is trichotomous on x,

- x is a transitive set totally ordered by set inclusion,

- x is a transitive set of transitive sets.

These definitions cannot be used in non-well-founded set theories. In set theories with urelements, one has to further make sure that the definition excludes urelements from appearing in ordinals.

Transfinite sequence[edit]

If α is any ordinal and X is a set, an α-indexed sequence of elements of X is a function from α to X. This concept, a transfinite sequence (if α is infinite) or ordinal-indexed sequence, is a generalization of the concept of a sequence. An ordinary sequence corresponds to the case α = ω, while a finite α corresponds to a tuple, a.k.a. string.

Transfinite induction[edit]

Transfinite induction holds in any well-ordered set, but it is so important in relation to ordinals that it is worth restating here.

- Any property that passes from the set of ordinals smaller than a given ordinal α to α itself, is true of all ordinals.

That is, if P(α) is true whenever P(β) is true for all β < α, then P(α) is true for all α. Or, more practically: in order to prove a property P for all ordinals α, one can assume that it is already known for all smaller β < α.

Transfinite recursion[edit]

Transfinite induction can be used not only to prove things, but also to define them. Such a definition is normally said to be by transfinite recursion – the proof that the result is well-defined uses transfinite induction. Let F denote a (class) function F to be defined on the ordinals. The idea now is that, in defining F(α) for an unspecified ordinal α, one may assume that F(β) is already defined for all β < α and thus give a formula for F(α) in terms of these F(β). It then follows by transfinite induction that there is one and only one function satisfying the recursion formula up to and including α.

Here is an example of definition by transfinite recursion on the ordinals (more will be given later): define function F by letting F(α) be the smallest ordinal not in the set {F(β) | β < α}, that is, the set consisting of all F(β) for β < α. This definition assumes the F(β) known in the very process of defining F; this apparent vicious circle is exactly what definition by transfinite recursion permits. In fact, F(0) makes sense since there is no ordinal β < 0, and the set {F(β) | β < 0} is empty. So F(0) is equal to 0 (the smallest ordinal of all). Now that F(0) is known, the definition applied to F(1) makes sense (it is the smallest ordinal not in the singleton set {F(0)} = {0}), and so on (the and so on is exactly transfinite induction). It turns out that this example is not very exciting, since provably F(α) = α for all ordinals α, which can be shown, precisely, by transfinite induction.

Successor and limit ordinals[edit]

Any nonzero ordinal has the minimum element, zero. It may or may not have a maximum element. For example, 42 has maximum 41 and ω+6 has maximum ω+5. On the other hand, ω does not have a maximum since there is no largest natural number. If an ordinal has a maximum α, then it is the next ordinal after α, and it is called a successor ordinal, namely the successor of α, written α+1. In the von Neumann definition of ordinals, the successor of α is

A nonzero ordinal that is not a successor is called a limit ordinal. One justification for this term is that a limit ordinal is the limit in a topological sense of all smaller ordinals (under the order topology).

When

Another way of defining a limit ordinal is to say that α is a limit ordinal if and only if:

- There is an ordinal less than α and whenever ζ is an ordinal less than α, then there exists an ordinal ξ such that ζ < ξ < α.

So in the following sequence:

- 0, 1, 2, …, ω, ω+1

ω is a limit ordinal because for any smaller ordinal (in this example, a natural number) there is another ordinal (natural number) larger than it, but still less than ω.

Thus, every ordinal is either zero, or a successor (of a well-defined predecessor), or a limit. This distinction is important, because many definitions by transfinite recursion rely upon it. Very often, when defining a function F by transfinite recursion on all ordinals, one defines F(0), and F(α+1) assuming F(α) is defined, and then, for limit ordinals δ one defines F(δ) as the limit of the F(β) for all β<δ (either in the sense of ordinal limits, as previously explained, or for some other notion of limit if F does not take ordinal values). Thus, the interesting step in the definition is the successor step, not the limit ordinals. Such functions (especially for F nondecreasing and taking ordinal values) are called continuous. Ordinal addition, multiplication and exponentiation are continuous as functions of their second argument (but can be defined non-recursively).

Indexing classes of ordinals[edit]

Any well-ordered set is similar (order-isomorphic) to a unique ordinal number

This could be applied, for example, to the class of limit ordinals: the

Closed unbounded sets and classes[edit]

A class

Of particular importance are those classes of ordinals that are closed and unbounded, sometimes called clubs. For example, the class of all limit ordinals is closed and unbounded: this translates the fact that there is always a limit ordinal greater than a given ordinal, and that a limit of limit ordinals is a limit ordinal (a fortunate fact if the terminology is to make any sense at all!). The class of additively indecomposable ordinals, or the class of

A class is stationary if it has a nonempty intersection with every closed unbounded class. All superclasses of closed unbounded classes are stationary, and stationary classes are unbounded, but there are stationary classes that are not closed and stationary classes that have no closed unbounded subclass (such as the class of all limit ordinals with countable cofinality). Since the intersection of two closed unbounded classes is closed and unbounded, the intersection of a stationary class and a closed unbounded class is stationary. But the intersection of two stationary classes may be empty, e.g. the class of ordinals with cofinality ω with the class of ordinals with uncountable cofinality.

Rather than formulating these definitions for (proper) classes of ordinals, one can formulate them for sets of ordinals below a given ordinal

Arithmetic of ordinals[edit]

There are three usual operations on ordinals: addition, multiplication, and (ordinal) exponentiation. Each can be defined in essentially two different ways: either by constructing an explicit well-ordered set that represents the operation or by using transfinite recursion. The Cantor normal form provides a standardized way of writing ordinals. It uniquely represents each ordinal as a finite sum of ordinal powers of ω. However, this cannot form the basis of a universal ordinal notation due to such self-referential representations as ε0 = ωε0. The so-called «natural» arithmetical operations retain commutativity at the expense of continuity.

Interpreted as nimbers (a game-theoretic variant of numbers), ordinals are also subject to nimber arithmetic operations.

Ordinals and cardinals[edit]

Initial ordinal of a cardinal[edit]

Each ordinal associates with one cardinal, its cardinality. If there is a bijection between two ordinals (e.g. ω = 1 + ω and ω + 1 > ω), then they associate with the same cardinal. Any well-ordered set having an ordinal as its order-type has the same cardinality as that ordinal. The least ordinal associated with a given cardinal is called the initial ordinal of that cardinal. Every finite ordinal (natural number) is initial, and no other ordinal associates with its cardinal. But most infinite ordinals are not initial, as many infinite ordinals associate with the same cardinal. The axiom of choice is equivalent to the statement that every set can be well-ordered, i.e. that every cardinal has an initial ordinal. In theories with the axiom of choice, the cardinal number of any set has an initial ordinal, and one may employ the Von Neumann cardinal assignment as the cardinal’s representation. (However, we must then be careful to distinguish between cardinal arithmetic and ordinal arithmetic.) In set theories without the axiom of choice, a cardinal may be represented by the set of sets with that cardinality having minimal rank (see Scott’s trick).

One issue with Scott’s trick is that it identifies the cardinal number

The α-th infinite initial ordinal is written

Cofinality[edit]

The cofinality of an ordinal

Thus for a limit ordinal, there exists a

The cofinality of 0 is 0. And the cofinality of any successor ordinal is 1. The cofinality of any limit ordinal is at least

An ordinal that is equal to its cofinality is called regular and it is always an initial ordinal. Any limit of regular ordinals is a limit of initial ordinals and thus is also initial even if it is not regular, which it usually is not. If the Axiom of Choice, then

The cofinality of any ordinal α is a regular ordinal, i.e. the cofinality of the cofinality of α is the same as the cofinality of α. So the cofinality operation is idempotent.

Some «large» countable ordinals[edit]

As mentioned above (see Cantor normal form), the ordinal ε0 is the smallest satisfying the equation

Topology and ordinals[edit]

Any ordinal number can be made into a topological space by endowing it with the order topology; this topology is discrete if and only if the ordinal is a countable cardinal, i.e. at most ω. A subset of ω + 1 is open in the order topology if and only if either it is cofinite or it does not contain ω as an element.

See the Topology and ordinals section of the «Order topology» article.

History[edit]

The transfinite ordinal numbers, which first appeared in 1883,[9] originated in Cantor’s work with derived sets. If P is a set of real numbers, the derived set P’ is the set of limit points of P. In 1872, Cantor generated the sets P(n) by applying the derived set operation n times to P. In 1880, he pointed out that these sets form the sequence P’ ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(n) ⊇ P(n + 1) ⊇ ···, and he continued the derivation process by defining P(∞) as the intersection of these sets. Then he iterated the derived set operation and intersections to extend his sequence of sets into the infinite: P(∞) ⊇ P(∞ + 1) ⊇ P(∞ + 2) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(2∞) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(∞2) ⊇ ···.[10] The superscripts containing ∞ are just indices defined by the derivation process.[11]

Cantor used these sets in the theorems: (1) If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P’ is countable; (2) Conversely, if P’ is countable, then there is an index α such that P(α) = ∅. These theorems are proved by partitioning P’ into pairwise disjoint sets: P’ = (P’ ∖ P(2)) ∪ (P(2) ∖ P(3)) ∪ ··· ∪ (P(∞) ∖ P(∞ + 1)) ∪ ··· ∪ P(α). For β < α: since P(β + 1) contains the limit points of P(β), the sets P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) have no limit points. Hence, they are discrete sets, so they are countable. Proof of first theorem: If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P’ is the countable union of countable sets. Therefore, P’ is countable.[12]

The second theorem requires proving the existence of an α such that P(α) = ∅. To prove this, Cantor considered the set of all α having countably many predecessors. To define this set, he defined the transfinite ordinal numbers and transformed the infinite indices into ordinals by replacing ∞ with ω, the first transfinite ordinal number. Cantor called the set of finite ordinals the first number class. The second number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a countably infinite set. The set of all α having countably many predecessors—that is, the set of countable ordinals—is the union of these two number classes. Cantor proved that the cardinality of the second number class is the first uncountable cardinality.[13]

Cantor’s second theorem becomes: If P’ is countable, then there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Its proof uses proof by contradiction. Let P’ be countable, and assume there is no such α. This assumption produces two cases.

- Case 1: P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) is non-empty for all countable β. Since there are uncountably many of these pairwise disjoint sets, their union is uncountable. This union is a subset of P’, so P’ is uncountable.

- Case 2: P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) is empty for some countable β. Since P(β + 1) ⊆ P(β), this implies P(β + 1) = P(β). Thus, P(β) is a perfect set, so it is uncountable.[14] Since P(β) ⊆ P’, the set P’ is uncountable.

In both cases, P’ is uncountable, which contradicts P’ being countable. Therefore, there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Cantor’s work with derived sets and ordinal numbers led to the Cantor-Bendixson theorem.[15]

Using successors, limits, and cardinality, Cantor generated an unbounded sequence of ordinal numbers and number classes.[16] The (α + 1)-th number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a set of the same cardinality as the α-th number class. The cardinality of the (α + 1)-th number class is the cardinality immediately following that of the α-th number class.[17] For a limit ordinal α, the α-th number class is the union of the β-th number classes for β < α.[18] Its cardinality is the limit of the cardinalities of these number classes.

If n is finite, the n-th number class has cardinality

See also[edit]

- Counting

- Even and odd ordinals

- First uncountable ordinal

- Ordinal space

- Surreal number, a generalization of ordinals which includes negatives

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Ordinal Number — Examples and Definition of Ordinal Number». Literary Devices. 2017-05-21. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Sterling, Kristin (2007-09-01). Ordinal Numbers. LernerClassroom. ISBN 978-0-8225-8846-7.

- ^ Thorough introductions are given by (Levy 1979) and (Jech 2003).

- ^ Hallett, Michael (1979), «Towards a theory of mathematical research programmes. I», The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 30 (1): 1–25, doi:10.1093/bjps/30.1.1, MR 0532548. See the footnote on p. 12.

- ^ «Ordinal Numbers | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki». brilliant.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Ordinal Number». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ a b von Neumann 1923

- ^ (Levy 1979, p. 52) attributes the idea to unpublished work of Zermelo in 1916 and several papers by von Neumann the 1920s.

- ^ Cantor 1883. English translation: Ewald 1996, pp. 881–920

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 34–35; Ferreirós 2007, pp. 159, 204–5

- ^ Ferreirós 2007, p. 269

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 35–36; Ferreirós 2007, p. 207

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 36–37; Ferreirós 2007, p. 271

- ^ Dauben 1979, p. 111

- ^ Ferreirós 2007, pp. 207–8

- ^ Dauben 1979, pp. 97–98

- ^ Hallett 1986, pp. 61–62

- ^ Tait 1997, p. 5 footnote

- ^ The first number class has cardinality

. Mathematical induction proves that the n-th number class has cardinality

. Since the ω-th number class is the union of the n-th number classes, its cardinality is

, the limit of the

. Transfinite induction proves that if α ≥ ω, the α-th number class has cardinality

.

References[edit]

- Cantor, Georg (1883), «Ueber unendliche, lineare Punktmannichfaltigkeiten. 5.», Mathematische Annalen, 21 (4): 545–591, doi:10.1007/bf01446819, S2CID 121930608. Published separately as: Grundlagen einer allgemeinen Mannigfaltigkeitslehre.

- Cantor, Georg (1897), «Beitrage zur Begrundung der transfiniten Mengenlehre. II», Mathematische Annalen, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 207–246, doi:10.1007/BF01444205, S2CID 121665994 English translation: Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers II.

- Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard (2012) [1996], «Cantor’s Ordinal Numbers», The Book of Numbers, Springer, pp. 266–7, 274, ISBN 978-1-4612-4072-3

- Dauben, Joseph (1979), Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-34871-0.

- Ewald, William B., ed. (1996), From Immanuel Kant to David Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, Volume 2, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-850536-1.

- Ferreirós, José (1995), «‘What fermented in me for years’: Cantor’s discovery of transfinite numbers» (PDF), Historia Mathematica, 22: 33–42, doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1003.

- Ferreirós, José (2007), Labyrinth of Thought: A History of Set Theory and Its Role in Mathematical Thought (2nd revised ed.), Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-3-7643-8349-7.

- Hallett, Michael (1986), Cantorian Set Theory and Limitation of Size, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-853283-0.

- Hamilton, A. G. (1982), «6. Ordinal and cardinal numbers», Numbers, Sets, and Axioms : the Apparatus of Mathematics, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24509-5.

- Kanamori, Akihiro (2012), «Set Theory from Cantor to Cohen» (PDF), in Gabbay, Dov M.; Kanamori, Akihiro; Woods, John H. (eds.), Sets and Extensions in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–71, ISBN 978-0-444-51621-3.

- Levy, A. (2002) [1979], Basic Set Theory, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-486-42079-5.

- Jech, Thomas (2013), Set Theory (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3-662-22400-7.

- Sierpiński, W. (1965), Cardinal and Ordinal Numbers (2nd ed.), Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Also defines ordinal operations in terms of the Cantor Normal Form.

- Suppes, Patrick (1960), Axiomatic Set Theory, D.Van Nostrand, ISBN 0-486-61630-4.

- Tait, William W. (1997), «Frege versus Cantor and Dedekind: On the Concept of Number» (PDF), in William W. Tait (ed.), Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, Open Court, pp. 213–248, ISBN 0-8126-9344-2.

- von Neumann, John (1923), «Zur Einführung der transfiniten Zahlen», Acta litterarum ac scientiarum Ragiae Universitatis Hungaricae Francisco-Josephinae, Sectio scientiarum mathematicarum, vol. 1, pp. 199–208, archived from the original on 2014-12-18, retrieved 2013-09-15

- von Neumann, John (January 2002) [1923], «On the introduction of transfinite numbers», in Jean van Heijenoort (ed.), From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931 (3rd ed.), Harvard University Press, pp. 346–354, ISBN 0-674-32449-8 — English translation of von Neumann 1923.

External links[edit]

![]()

Look up ordinal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Ordinal number», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Ordinals at ProvenMath

- Ordinal calculator GPL’d free software for computing with ordinals and ordinal notations

- Chapter 4 of Don Monk’s lecture notes on set theory is an introduction to ordinals.

This article is about the mathematical concept. For number words denoting a position in a sequence («first», «second», «third», etc.), see Ordinal numeral.

Representation of the ordinal numbers up to ωω. Each turn of the spiral represents one power of ω.

In set theory, an ordinal number, or ordinal, is a generalization of ordinal numerals (first, second, nth, etc.) aimed to extend enumeration to infinite sets.[1]

A finite set can be enumerated by successively labeling each element with the least natural number that has not been previously used. To extend this process to various infinite sets, ordinal numbers are defined more generally as linearly ordered labels that include the natural numbers and have the property that every set of ordinals has a least element (this is needed for giving a meaning to «the least unused element»).[2] This more general definition allows us to define an ordinal number

A linear order such that every subset has a least element is called a well-order. The axiom of choice implies that every set can be well-ordered, and given two well-ordered sets, one is isomorphic to an initial segment of the other. So ordinal numbers exist and are essentially unique.

Ordinal numbers are distinct from cardinal numbers, which measure the size of sets. Although the distinction between ordinals and cardinals is not always apparent on finite sets (one can go from one to the other just by counting labels), they are very different in the infinite case, where different infinite ordinals can correspond to sets having the same cardinal. Like other kinds of numbers, ordinals can be added, multiplied, and exponentiated, although none of these operations are commutative.

Ordinals were introduced by Georg Cantor in 1883[3] in order to accommodate infinite sequences and classify derived sets, which he had previously introduced in 1872 while studying the uniqueness of trigonometric series.[4]

Ordinals extend the natural numbers[edit]

A natural number (which, in this context, includes the number 0) can be used for two purposes: to describe the size of a set, or to describe the position of an element in a sequence. When restricted to finite sets, these two concepts coincide, since all linear orders of a finite set are isomorphic.

When dealing with infinite sets, however, one has to distinguish between the notion of size, which leads to cardinal numbers, and the notion of position, which leads to the ordinal numbers described here. This is because while any set has only one size (its cardinality), there are many nonisomorphic well-orderings of any infinite set, as explained below.

Whereas the notion of cardinal number is associated with a set with no particular structure on it, the ordinals are intimately linked with the special kind of sets that are called well-ordered. A well-ordered set is a totally ordered set in which every non-empty subset has a least element (a totally ordered set is an ordered set such that, given two distinct elements, one is less than the other). Equivalently, assuming the axiom of dependent choice, it is a totally ordered set without any infinite decreasing sequence — though there may be infinite increasing sequences. Ordinals may be used to label the elements of any given well-ordered set (the smallest element being labelled 0, the one after that 1, the next one 2, «and so on»), and to measure the «length» of the whole set by the least ordinal that is not a label for an element of the set. This «length» is called the order type of the set.

Any ordinal is defined by the set of ordinals that precede it. In fact, the most common definition of ordinals identifies each ordinal as the set of ordinals that precede it. For example, the ordinal 42 is generally identified as the set {0, 1, 2, …, 41}. Conversely, any set S of ordinals that is downward closed — meaning that for any ordinal α in S and any ordinal β < α, β is also in S — is (or can be identified with) an ordinal.

This definition of ordinals in terms of sets allows for infinite ordinals. The smallest infinite ordinal is

A graphical «matchstick» representation of the ordinal ω². Each stick corresponds to an ordinal of the form ω·m+n where m and n are natural numbers.

Perhaps a clearer intuition of ordinals can be formed by examining a first few of them: as mentioned above, they start with the natural numbers, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, … After all natural numbers comes the first infinite ordinal, ω, and after that come ω+1, ω+2, ω+3, and so on. (Exactly what addition means will be defined later on: just consider them as names.) After all of these come ω·2 (which is ω+ω), ω·2+1, ω·2+2, and so on, then ω·3, and then later on ω·4. Now the set of ordinals formed in this way (the ω·m+n, where m and n are natural numbers) must itself have an ordinal associated with it: and that is ω2. Further on, there will be ω3, then ω4, and so on, and ωω, then ωωω, then later ωωωω, and even later ε0 (epsilon nought) (to give a few examples of relatively small—countable—ordinals). This can be continued indefinitely (as every time one says «and so on» when enumerating ordinals, it defines a larger ordinal). The smallest uncountable ordinal is the set of all countable ordinals, expressed as ω1 or

Definitions[edit]

Well-ordered sets[edit]

In a well-ordered set, every non-empty subset contains a distinct smallest element. Given the axiom of dependent choice, this is equivalent to saying that the set is totally ordered and there is no infinite decreasing sequence (the latter being easier to visualize). In practice, the importance of well-ordering is justified by the possibility of applying transfinite induction, which says, essentially, that any property that passes on from the predecessors of an element to that element itself must be true of all elements (of the given well-ordered set). If the states of a computation (computer program or game) can be well-ordered—in such a way that each step is followed by a «lower» step—then the computation will terminate.

It is inappropriate to distinguish between two well-ordered sets if they only differ in the «labeling of their elements», or more formally: if the elements of the first set can be paired off with the elements of the second set such that if one element is smaller than another in the first set, then the partner of the first element is smaller than the partner of the second element in the second set, and vice versa. Such a one-to-one correspondence is called an order isomorphism, and the two well-ordered sets are said to be order-isomorphic or similar (with the understanding that this is an equivalence relation).

Formally, if a partial order ≤ is defined on the set S, and a partial order ≤’ is defined on the set S’ , then the posets (S,≤) and (S’ ,≤’) are order isomorphic if there is a bijection f that preserves the ordering. That is, f(a) ≤’ f(b) if and only if a ≤ b. Provided there exists an order isomorphism between two well-ordered sets, the order isomorphism is unique: this makes it quite justifiable to consider the two sets as essentially identical, and to seek a «canonical» representative of the isomorphism type (class). This is exactly what the ordinals provide, and it also provides a canonical labeling of the elements of any well-ordered set. Every well-ordered set (S,<) is order-isomorphic to the set of ordinals less than one specific ordinal number under their natural ordering. This canonical set is the order type of (S,<).

Essentially, an ordinal is intended to be defined as an isomorphism class of well-ordered sets: that is, as an equivalence class for the equivalence relation of «being order-isomorphic». There is a technical difficulty involved, however, in the fact that the equivalence class is too large to be a set in the usual Zermelo–Fraenkel (ZF) formalization of set theory. But this is not a serious difficulty. The ordinal can be said to be the order type of any set in the class.

Definition of an ordinal as an equivalence class[edit]

The original definition of ordinal numbers, found for example in the Principia Mathematica, defines the order type of a well-ordering as the set of all well-orderings similar (order-isomorphic) to that well-ordering: in other words, an ordinal number is genuinely an equivalence class of well-ordered sets. This definition must be abandoned in ZF and related systems of axiomatic set theory because these equivalence classes are too large to form a set. However, this definition still can be used in type theory and in Quine’s axiomatic set theory New Foundations and related systems (where it affords a rather surprising alternative solution to the Burali-Forti paradox of the largest ordinal).

Von Neumann definition of ordinals[edit]

| 0 | = | {} | = | ∅ |

| 1 | = | {0} | = | {∅} |

| 2 | = | {0,1} | = | {∅,{∅}} |

| 3 | = | {0,1,2} | = | {∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}}} |

| 4 | = | {0,1,2,3} | = | {∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}},{∅,{∅},{∅,{∅}}}} |

Rather than defining an ordinal as an equivalence class of well-ordered sets, it will be defined as a particular well-ordered set that (canonically) represents the class. Thus, an ordinal number will be a well-ordered set; and every well-ordered set will be order-isomorphic to exactly one ordinal number.

For each well-ordered set

- A set S is an ordinal if and only if S is strictly well-ordered with respect to set membership and every element of S is also a subset of S.

The natural numbers are thus ordinals by this definition. For instance, 2 is an element of 4 = {0, 1, 2, 3}, and 2 is equal to {0, 1} and so it is a subset of {0, 1, 2, 3}.

It can be shown by transfinite induction that every well-ordered set is order-isomorphic to exactly one of these ordinals, that is, there is an order preserving bijective function between them.

Furthermore, the elements of every ordinal are ordinals themselves. Given two ordinals S and T, S is an element of T if and only if S is a proper subset of T. Moreover, either S is an element of T, or T is an element of S, or they are equal. So every set of ordinals is totally ordered. Further, every set of ordinals is well-ordered. This generalizes the fact that every set of natural numbers is well-ordered.

Consequently, every ordinal S is a set having as elements precisely the ordinals smaller than S. For example, every set of ordinals has a supremum, the ordinal obtained by taking the union of all the ordinals in the set. This union exists regardless of the set’s size, by the axiom of union.

The class of all ordinals is not a set. If it were a set, one could show that it was an ordinal and thus a member of itself, which would contradict its strict ordering by membership. This is the Burali-Forti paradox. The class of all ordinals is variously called «Ord», «ON», or «∞».

An ordinal is finite if and only if the opposite order is also well-ordered, which is the case if and only if each of its non-empty subsets has a maximum.

Other definitions[edit]

There are other modern formulations of the definition of ordinal. For example, assuming the axiom of regularity, the following are equivalent for a set x:

- x is a (von Neumann) ordinal,

- x is a transitive set, and set membership is trichotomous on x,

- x is a transitive set totally ordered by set inclusion,

- x is a transitive set of transitive sets.

These definitions cannot be used in non-well-founded set theories. In set theories with urelements, one has to further make sure that the definition excludes urelements from appearing in ordinals.

Transfinite sequence[edit]

If α is any ordinal and X is a set, an α-indexed sequence of elements of X is a function from α to X. This concept, a transfinite sequence (if α is infinite) or ordinal-indexed sequence, is a generalization of the concept of a sequence. An ordinary sequence corresponds to the case α = ω, while a finite α corresponds to a tuple, a.k.a. string.

Transfinite induction[edit]

Transfinite induction holds in any well-ordered set, but it is so important in relation to ordinals that it is worth restating here.

- Any property that passes from the set of ordinals smaller than a given ordinal α to α itself, is true of all ordinals.

That is, if P(α) is true whenever P(β) is true for all β < α, then P(α) is true for all α. Or, more practically: in order to prove a property P for all ordinals α, one can assume that it is already known for all smaller β < α.

Transfinite recursion[edit]

Transfinite induction can be used not only to prove things, but also to define them. Such a definition is normally said to be by transfinite recursion – the proof that the result is well-defined uses transfinite induction. Let F denote a (class) function F to be defined on the ordinals. The idea now is that, in defining F(α) for an unspecified ordinal α, one may assume that F(β) is already defined for all β < α and thus give a formula for F(α) in terms of these F(β). It then follows by transfinite induction that there is one and only one function satisfying the recursion formula up to and including α.

Here is an example of definition by transfinite recursion on the ordinals (more will be given later): define function F by letting F(α) be the smallest ordinal not in the set {F(β) | β < α}, that is, the set consisting of all F(β) for β < α. This definition assumes the F(β) known in the very process of defining F; this apparent vicious circle is exactly what definition by transfinite recursion permits. In fact, F(0) makes sense since there is no ordinal β < 0, and the set {F(β) | β < 0} is empty. So F(0) is equal to 0 (the smallest ordinal of all). Now that F(0) is known, the definition applied to F(1) makes sense (it is the smallest ordinal not in the singleton set {F(0)} = {0}), and so on (the and so on is exactly transfinite induction). It turns out that this example is not very exciting, since provably F(α) = α for all ordinals α, which can be shown, precisely, by transfinite induction.

Successor and limit ordinals[edit]

Any nonzero ordinal has the minimum element, zero. It may or may not have a maximum element. For example, 42 has maximum 41 and ω+6 has maximum ω+5. On the other hand, ω does not have a maximum since there is no largest natural number. If an ordinal has a maximum α, then it is the next ordinal after α, and it is called a successor ordinal, namely the successor of α, written α+1. In the von Neumann definition of ordinals, the successor of α is

A nonzero ordinal that is not a successor is called a limit ordinal. One justification for this term is that a limit ordinal is the limit in a topological sense of all smaller ordinals (under the order topology).

When

Another way of defining a limit ordinal is to say that α is a limit ordinal if and only if:

- There is an ordinal less than α and whenever ζ is an ordinal less than α, then there exists an ordinal ξ such that ζ < ξ < α.

So in the following sequence:

- 0, 1, 2, …, ω, ω+1

ω is a limit ordinal because for any smaller ordinal (in this example, a natural number) there is another ordinal (natural number) larger than it, but still less than ω.

Thus, every ordinal is either zero, or a successor (of a well-defined predecessor), or a limit. This distinction is important, because many definitions by transfinite recursion rely upon it. Very often, when defining a function F by transfinite recursion on all ordinals, one defines F(0), and F(α+1) assuming F(α) is defined, and then, for limit ordinals δ one defines F(δ) as the limit of the F(β) for all β<δ (either in the sense of ordinal limits, as previously explained, or for some other notion of limit if F does not take ordinal values). Thus, the interesting step in the definition is the successor step, not the limit ordinals. Such functions (especially for F nondecreasing and taking ordinal values) are called continuous. Ordinal addition, multiplication and exponentiation are continuous as functions of their second argument (but can be defined non-recursively).

Indexing classes of ordinals[edit]

Any well-ordered set is similar (order-isomorphic) to a unique ordinal number

This could be applied, for example, to the class of limit ordinals: the

Closed unbounded sets and classes[edit]

A class

Of particular importance are those classes of ordinals that are closed and unbounded, sometimes called clubs. For example, the class of all limit ordinals is closed and unbounded: this translates the fact that there is always a limit ordinal greater than a given ordinal, and that a limit of limit ordinals is a limit ordinal (a fortunate fact if the terminology is to make any sense at all!). The class of additively indecomposable ordinals, or the class of

A class is stationary if it has a nonempty intersection with every closed unbounded class. All superclasses of closed unbounded classes are stationary, and stationary classes are unbounded, but there are stationary classes that are not closed and stationary classes that have no closed unbounded subclass (such as the class of all limit ordinals with countable cofinality). Since the intersection of two closed unbounded classes is closed and unbounded, the intersection of a stationary class and a closed unbounded class is stationary. But the intersection of two stationary classes may be empty, e.g. the class of ordinals with cofinality ω with the class of ordinals with uncountable cofinality.

Rather than formulating these definitions for (proper) classes of ordinals, one can formulate them for sets of ordinals below a given ordinal

Arithmetic of ordinals[edit]

There are three usual operations on ordinals: addition, multiplication, and (ordinal) exponentiation. Each can be defined in essentially two different ways: either by constructing an explicit well-ordered set that represents the operation or by using transfinite recursion. The Cantor normal form provides a standardized way of writing ordinals. It uniquely represents each ordinal as a finite sum of ordinal powers of ω. However, this cannot form the basis of a universal ordinal notation due to such self-referential representations as ε0 = ωε0. The so-called «natural» arithmetical operations retain commutativity at the expense of continuity.

Interpreted as nimbers (a game-theoretic variant of numbers), ordinals are also subject to nimber arithmetic operations.

Ordinals and cardinals[edit]

Initial ordinal of a cardinal[edit]

Each ordinal associates with one cardinal, its cardinality. If there is a bijection between two ordinals (e.g. ω = 1 + ω and ω + 1 > ω), then they associate with the same cardinal. Any well-ordered set having an ordinal as its order-type has the same cardinality as that ordinal. The least ordinal associated with a given cardinal is called the initial ordinal of that cardinal. Every finite ordinal (natural number) is initial, and no other ordinal associates with its cardinal. But most infinite ordinals are not initial, as many infinite ordinals associate with the same cardinal. The axiom of choice is equivalent to the statement that every set can be well-ordered, i.e. that every cardinal has an initial ordinal. In theories with the axiom of choice, the cardinal number of any set has an initial ordinal, and one may employ the Von Neumann cardinal assignment as the cardinal’s representation. (However, we must then be careful to distinguish between cardinal arithmetic and ordinal arithmetic.) In set theories without the axiom of choice, a cardinal may be represented by the set of sets with that cardinality having minimal rank (see Scott’s trick).

One issue with Scott’s trick is that it identifies the cardinal number

The α-th infinite initial ordinal is written

Cofinality[edit]

The cofinality of an ordinal

Thus for a limit ordinal, there exists a

The cofinality of 0 is 0. And the cofinality of any successor ordinal is 1. The cofinality of any limit ordinal is at least

An ordinal that is equal to its cofinality is called regular and it is always an initial ordinal. Any limit of regular ordinals is a limit of initial ordinals and thus is also initial even if it is not regular, which it usually is not. If the Axiom of Choice, then

The cofinality of any ordinal α is a regular ordinal, i.e. the cofinality of the cofinality of α is the same as the cofinality of α. So the cofinality operation is idempotent.

Some «large» countable ordinals[edit]

As mentioned above (see Cantor normal form), the ordinal ε0 is the smallest satisfying the equation

Topology and ordinals[edit]

Any ordinal number can be made into a topological space by endowing it with the order topology; this topology is discrete if and only if the ordinal is a countable cardinal, i.e. at most ω. A subset of ω + 1 is open in the order topology if and only if either it is cofinite or it does not contain ω as an element.

See the Topology and ordinals section of the «Order topology» article.

History[edit]

The transfinite ordinal numbers, which first appeared in 1883,[9] originated in Cantor’s work with derived sets. If P is a set of real numbers, the derived set P’ is the set of limit points of P. In 1872, Cantor generated the sets P(n) by applying the derived set operation n times to P. In 1880, he pointed out that these sets form the sequence P’ ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(n) ⊇ P(n + 1) ⊇ ···, and he continued the derivation process by defining P(∞) as the intersection of these sets. Then he iterated the derived set operation and intersections to extend his sequence of sets into the infinite: P(∞) ⊇ P(∞ + 1) ⊇ P(∞ + 2) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(2∞) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(∞2) ⊇ ···.[10] The superscripts containing ∞ are just indices defined by the derivation process.[11]

Cantor used these sets in the theorems: (1) If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P’ is countable; (2) Conversely, if P’ is countable, then there is an index α such that P(α) = ∅. These theorems are proved by partitioning P’ into pairwise disjoint sets: P’ = (P’ ∖ P(2)) ∪ (P(2) ∖ P(3)) ∪ ··· ∪ (P(∞) ∖ P(∞ + 1)) ∪ ··· ∪ P(α). For β < α: since P(β + 1) contains the limit points of P(β), the sets P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) have no limit points. Hence, they are discrete sets, so they are countable. Proof of first theorem: If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P’ is the countable union of countable sets. Therefore, P’ is countable.[12]

The second theorem requires proving the existence of an α such that P(α) = ∅. To prove this, Cantor considered the set of all α having countably many predecessors. To define this set, he defined the transfinite ordinal numbers and transformed the infinite indices into ordinals by replacing ∞ with ω, the first transfinite ordinal number. Cantor called the set of finite ordinals the first number class. The second number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a countably infinite set. The set of all α having countably many predecessors—that is, the set of countable ordinals—is the union of these two number classes. Cantor proved that the cardinality of the second number class is the first uncountable cardinality.[13]

Cantor’s second theorem becomes: If P’ is countable, then there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Its proof uses proof by contradiction. Let P’ be countable, and assume there is no such α. This assumption produces two cases.

- Case 1: P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) is non-empty for all countable β. Since there are uncountably many of these pairwise disjoint sets, their union is uncountable. This union is a subset of P’, so P’ is uncountable.

- Case 2: P(β) ∖ P(β + 1) is empty for some countable β. Since P(β + 1) ⊆ P(β), this implies P(β + 1) = P(β). Thus, P(β) is a perfect set, so it is uncountable.[14] Since P(β) ⊆ P’, the set P’ is uncountable.

In both cases, P’ is uncountable, which contradicts P’ being countable. Therefore, there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Cantor’s work with derived sets and ordinal numbers led to the Cantor-Bendixson theorem.[15]

Using successors, limits, and cardinality, Cantor generated an unbounded sequence of ordinal numbers and number classes.[16] The (α + 1)-th number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a set of the same cardinality as the α-th number class. The cardinality of the (α + 1)-th number class is the cardinality immediately following that of the α-th number class.[17] For a limit ordinal α, the α-th number class is the union of the β-th number classes for β < α.[18] Its cardinality is the limit of the cardinalities of these number classes.

If n is finite, the n-th number class has cardinality

See also[edit]

- Counting

- Even and odd ordinals

- First uncountable ordinal

- Ordinal space

- Surreal number, a generalization of ordinals which includes negatives

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Ordinal Number — Examples and Definition of Ordinal Number». Literary Devices. 2017-05-21. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Sterling, Kristin (2007-09-01). Ordinal Numbers. LernerClassroom. ISBN 978-0-8225-8846-7.

- ^ Thorough introductions are given by (Levy 1979) and (Jech 2003).

- ^ Hallett, Michael (1979), «Towards a theory of mathematical research programmes. I», The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 30 (1): 1–25, doi:10.1093/bjps/30.1.1, MR 0532548. See the footnote on p. 12.

- ^ «Ordinal Numbers | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki». brilliant.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Ordinal Number». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ a b von Neumann 1923

- ^ (Levy 1979, p. 52) attributes the idea to unpublished work of Zermelo in 1916 and several papers by von Neumann the 1920s.

- ^ Cantor 1883. English translation: Ewald 1996, pp. 881–920

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 34–35; Ferreirós 2007, pp. 159, 204–5

- ^ Ferreirós 2007, p. 269

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 35–36; Ferreirós 2007, p. 207

- ^ Ferreirós 1995, pp. 36–37; Ferreirós 2007, p. 271

- ^ Dauben 1979, p. 111

- ^ Ferreirós 2007, pp. 207–8

- ^ Dauben 1979, pp. 97–98

- ^ Hallett 1986, pp. 61–62

- ^ Tait 1997, p. 5 footnote

- ^ The first number class has cardinality

. Mathematical induction proves that the n-th number class has cardinality

. Since the ω-th number class is the union of the n-th number classes, its cardinality is

, the limit of the

. Transfinite induction proves that if α ≥ ω, the α-th number class has cardinality

.

References[edit]

- Cantor, Georg (1883), «Ueber unendliche, lineare Punktmannichfaltigkeiten. 5.», Mathematische Annalen, 21 (4): 545–591, doi:10.1007/bf01446819, S2CID 121930608. Published separately as: Grundlagen einer allgemeinen Mannigfaltigkeitslehre.

- Cantor, Georg (1897), «Beitrage zur Begrundung der transfiniten Mengenlehre. II», Mathematische Annalen, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 207–246, doi:10.1007/BF01444205, S2CID 121665994 English translation: Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers II.

- Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard (2012) [1996], «Cantor’s Ordinal Numbers», The Book of Numbers, Springer, pp. 266–7, 274, ISBN 978-1-4612-4072-3

- Dauben, Joseph (1979), Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-34871-0.

- Ewald, William B., ed. (1996), From Immanuel Kant to David Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, Volume 2, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-850536-1.

- Ferreirós, José (1995), «‘What fermented in me for years’: Cantor’s discovery of transfinite numbers» (PDF), Historia Mathematica, 22: 33–42, doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1003.

- Ferreirós, José (2007), Labyrinth of Thought: A History of Set Theory and Its Role in Mathematical Thought (2nd revised ed.), Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-3-7643-8349-7.

- Hallett, Michael (1986), Cantorian Set Theory and Limitation of Size, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-853283-0.

- Hamilton, A. G. (1982), «6. Ordinal and cardinal numbers», Numbers, Sets, and Axioms : the Apparatus of Mathematics, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24509-5.

- Kanamori, Akihiro (2012), «Set Theory from Cantor to Cohen» (PDF), in Gabbay, Dov M.; Kanamori, Akihiro; Woods, John H. (eds.), Sets and Extensions in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–71, ISBN 978-0-444-51621-3.

- Levy, A. (2002) [1979], Basic Set Theory, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-486-42079-5.

- Jech, Thomas (2013), Set Theory (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3-662-22400-7.

- Sierpiński, W. (1965), Cardinal and Ordinal Numbers (2nd ed.), Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Also defines ordinal operations in terms of the Cantor Normal Form.

- Suppes, Patrick (1960), Axiomatic Set Theory, D.Van Nostrand, ISBN 0-486-61630-4.

- Tait, William W. (1997), «Frege versus Cantor and Dedekind: On the Concept of Number» (PDF), in William W. Tait (ed.), Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, Open Court, pp. 213–248, ISBN 0-8126-9344-2.

- von Neumann, John (1923), «Zur Einführung der transfiniten Zahlen», Acta litterarum ac scientiarum Ragiae Universitatis Hungaricae Francisco-Josephinae, Sectio scientiarum mathematicarum, vol. 1, pp. 199–208, archived from the original on 2014-12-18, retrieved 2013-09-15

- von Neumann, John (January 2002) [1923], «On the introduction of transfinite numbers», in Jean van Heijenoort (ed.), From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931 (3rd ed.), Harvard University Press, pp. 346–354, ISBN 0-674-32449-8 — English translation of von Neumann 1923.

External links[edit]

![]()

Look up ordinal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Ordinal number», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Ordinals at ProvenMath

- Ordinal calculator GPL’d free software for computing with ordinals and ordinal notations

- Chapter 4 of Don Monk’s lecture notes on set theory is an introduction to ordinals.

В статье рассмотрена расшифровка таблицы Менделеева, с помощью которой можно быстро в ней разобраться. Из таблицы Менделеева можно почерпнуть огромное количество информации о каждом химическом элементе. Ее можно использовать на ЕГЭ, если уметь грамотно ей пользоваться.

В статье рассмотрена расшифровка таблицы Менделеева, с помощью которой можно быстро в ней разобраться. Из таблицы Менделеева можно почерпнуть огромное количество информации о каждом химическом элементе. Ее можно использовать на ЕГЭ, если уметь грамотно ей пользоваться.

- Периодическая система Менделеева систематизирует элементы и их свойства. В ней все элементы упорядочены с учетом их атомного числа и повторяющихся химических свойств.

- Периодический закон: свойства простых веществ, а также свойства и формы соединений элементов находятся в периодической зависимости от заряда ядра атомов элементов (порядкового номера).

Расшифровка обозначений элементов

Каждому химическому элементу в таблице отведена одна клеточка, в которой указаны символ и название элемента, порядковый номер и относительная атомная масса.

Расшифровка обозначений элементов таблицы Менделеева:

- Обозначение: одной или двумя латинскими буквами.

- Порядковый номер элемента или атомный номер равен числу протонов в его ядре. Обычно пишется в левом верхнем углу.

- Относительная атомная масса (сумма масс протонов и нейтронов). Это усреднённая величина, для расчёта которой используются атомные массы всех изотопов элемента с учетом их содержания в природе. Поэтому обычно она является дробным числом.

- Если округлить атомную массу до ближайшего целого, мы получим так называемое массовое число.

- Разность массового числа и атомного числа дает количество нейтронов в ядре. Так, число нейтронов в ядре гелия равно двум, а у лития – четырем.

- Число положительных протонов, как правило, равно числу отрицательных электронов в атоме (за исключением изотопов).

- Электронная конфигурация — формула расположения электронов по различным электронным оболочкам атома химического элемента или молекулы.

-

Чтобы узнать количество нейтронов в ядре элемента, необходимо из относительной атомной массы (массового числа) вычесть порядковый номер.

Элементы периодической таблицы Менделеева

Металлы расположены в левом нижнем углу таблицы, неметаллы — в правом верхнем углу. Между ними находятся полуметаллы. Все периоды, кроме первого, начинается щелочным металлом. Каждый период заканчивается инертным газом.

- Металлы обладают хорошей электро- и теплопроводностью, способны отражать яркий свет, имеют высокую температуру плавления (остаются твердыми при нормальных значениях окружающей среды, исключение — ртуть).

- Неметаллы встречаются в природе в трех состояниях: газ (например, водород), жидкость (например, бром) и твердые вещества (например, фосфор). Он не способны проводить тепло и электричество. Имеют более низкую температуру плавления в сравнении с металлами, более хрупкие и ломкие. Могут иметь разнообразный внешний вид (элементы с низкой плотностью и яркостью).

- Металлоиды имеют смешанные свойства металлов и неметаллов (например, кремний). Они имеют среднюю тепло- и электропроводность. Различаются между собой по температуре плавления, плотности, цвету и форме. Внешний вид может быть схож с металлами или неметаллами.

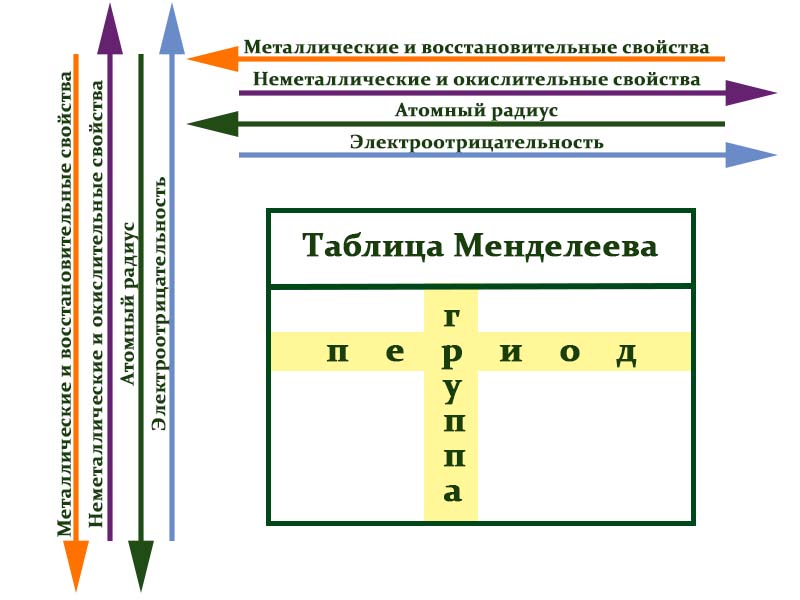

Расшифровка групп и периодов таблицы Менделеева

В таблице химические вещества расположены в специальном порядке: слева направо по мере роста их атомных масс. Все они в периодической системе объединены в периоды и группы.

Периоды — это горизонтальные ряды в таблице. У всех элементов одного периода одинаковое количество заполненных электронами энергетических уровней.

Номер периода, в котором находится элемент, совпадает с номером его валентной оболочки. Эта валентная оболочка постепенно заполняется от начала к концу периода.

Закономерности периодов:

- Металлические свойства убывают, неметаллические и окислительные -возрастают. Каждый период начинается активным металлом и заканчивается инертным газом.

- Уменьшается атомный радиус.

- Увеличивается электроотрицательность.

Группы — это столбцы. Элементы во всех группах имеют одинаковое электронное строение внешних электронных оболочек. В каждой группе на внешнем энергетическом атома одинаковое число электронов, то есть номер группы совпадает с числом валентных электронов, которые могут участвовать в образовании химических связей. Поэтому номер группы часто совпадает с валентностью элементов. Например, номер группы совпадает с валентностью s-элементов и с наибольшей возможной валентностью p-элементов.

Закономерности групп:

- Металлические свойства увеличиваются, неметаллические и окислительные- убывают.

- Увеличивается радиус атома элементов в рамках одной группы.

- Уменьшается электроотрицательность.

Атомное число показывает, сколько протонов содержит ядро атома элемента и сколько электронов в атоме находятся вокруг него. Атом каждого последующего элемента содержит на один протон больше, чем предыдущий.

Валетность — это свойство элементов образовывать химические связи. То есть это количество химических связей, которые образует атом или число атомов, которое может присоединить или заместить атом данного элемента. Валентность бывает: постоянная и переменная (зависит от состава вещества, в которое входит элемент).

Определить валентность:

— Постоянная валентность идентична номеру группы главной подгруппы. Номера групп в таблице изображаются римскими цифрами.

— Переменная валентность (часто бывает у неметаллов) определяется по формуле: 8 вычесть № группы, в которой находится вещество.

Расшифровка периодов и групп периодической таблицы Менделеева

Каждый элемент имеет свой порядковый (атомный) номер, располагается в определённом периоде и определённой группе.

Периоды

- Малые периоды: первый, второй и третий периоды. В них содержится соответственно 2, 8 и 8 элементов;

- Большие периоды: остальные элементы. В четвёртом и пятом периодах расположены по 18 элементов, в шестом — 32, а в седьмом (пока незавершенном) — 31 элемент.

В таблице 7 периодов. В каждом содержится определённое число элементов:

1-й период — 2 элемента (малый период),

2-й период — 8 элементов (малый период),

3-й период — 8 элементов (малый период),

4-й период — 18 элементов (большой период),

5-й период — 18 элементов (большой период),

6-й период — 32 элемента (18+14) (большой период),

7-й период — 32 элемента (18+14) (большой период).

Группы и подгруппы

- Главные подгруппы включают в себя элементы малых периодов и одинаковые с ним по свойствам элементы больших периодов.

- Побочные подгруппы состоят только из элементов больших периодов. Химические свойства элементов главных и побочных подгрупп значительно различаются.

В Периодической таблице может использоваться разное обозначение групп. Поэтому согласно такому обозначению бывает разная расшифровка групп таблицы менделеева:

- 18 групп, пронумерованных арабскими цифрами.

- 8 групп, пронумерованных цифрами с добавлением букв A или B.

Группы A — это главные подгруппы.

Группы B — это побочные подгруппы в больших периодов. Это только металлы.

IA, VIIIA — по 7 элементов;

IIA — VIIA — по 6 элементов;

IIIB — 32 элемента (4+14 лантаноидов +14 актиноидов);

VIIIB — 12 элементов;

IB, IIB, IVB — VIIB — по 4 элемента.

Римский номер группы, как правило, показывает высшую валентность в оксидах (но для некоторых элементов не выполняется).

Элементы с порядковыми номерами 58–71 (лантаноиды) и 90–103 (актиноиды) вынесены из таблицы и располагаются под ней. Это элементы IIIB группы. Лантаноиды относятся к шестому периоду, а актиноиды — к седьмому.

Элементы главной подгруппы

1 группа главная подгруппа элементов (IA) — щелочные металлы.

Это мягкие металлы, серебристого цвета, хорошо режутся ножом. Все они обладают одним электроном на внешней оболочке и прекрасно вступают в реакцию.

Литий Li (3), Натрий Na (11), Калий K (19), Рубидий Rb (37), Цезий Cs (55), Франций Fr (87).

2 группа главная подгруппа (IIА) -щелочноземельными металлами.

Имеют серебристый оттенок. На внешнем уровне помещено по два электрона, и, соответственно, эти металлы менее охотно взаимодействуют с другими элементами. По сравнению со щелочными металлами, щелочноземельные металлы плавятся и кипят при более высоких температурах.

Кальций Ca (20), Стронций Sr (38), Барий Ba (56), Радий Ra (88).

3 группа главная подгруппа (IIIА).

Все элементы данной подгруппы, за исключением бора, металлы. Главную подгруппу составляют составляют бор, алюминий, галлий, индий и таллий. На внешнем электронном уровне элементов по три электрона. Они легко отдают эти электроны или образуют три неспаренных электрона.

4 группа главная подгруппа (IVА) .

Углерод и кремний обладают всеми свойствами неметаллов, германий и олово занимают промежуточную позицию, а свинец имеет выраженные металлические свойства. Большинство элементов подгруппы углерода — полупроводники (проводят электричество за счёт примесей, но хуже, чем металлы).

5 группа главная подгруппа (VA).

Физические свойства элементов подгруппы азота различны. Азот является бесцветным газом. Фосфор, мягкое вещество, образует несколько вариантов аллотропных модификаций — белый, красный и чёрный фосфор. Мышьяк — твёрдый полуметалл, способный проводить электрический ток. Висмут — блестящий серебристо-белый металл с радужным отливом.

6 группа главной подгруппы (VIA) .

Для завершения внешнего электронного уровня атомам этих элементов не хватает лишь двух электронов, поэтому они проявляют сильные окислительные (неметаллические) свойства.

7 группа главная подгруппа (VIIA) — галогены .

(F, Cl, Br, I, At). Имеют семь электронов на внешнем электронном слое атома. Это сильнейшие окислители, легко вступающие в реакции. Галогены («рождающие соли») назвали так потому, что они реагируют со многими металлами с образованием солей.

Самый активный из галогенов — фтор. Он способен разрушать даже молекулы воды, за что и получил своё грозное имя (слово «фтор» переводится на русский язык как «разрушительный»). А его «близкий родственник» — иод — используется в медицине в виде спиртового раствора для обработки ран.

8 группа главная подгруппа (VIIIA) — инертные (благородные) газы.

(He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn, Og). У них полностью заполнен внешний электронный уровень. Они практически не способны участвовать в реакциях. Поэтому их иногда называют «благородными». У инертных газов есть способность: они светятся под действием электромагнитного излучения, поэтому используются для создания ламп. Так, неон используется для создания светящихся вывесок и реклам, а ксенон — в автомобильных фарах и фотовспышках.

Элементы побочной подгруппы

Элементы побочных подгрупп кроме лантаноидов и актиноидов — переходные металлы.

Твёрдые (исключение жидкая ртуть), плотные, обладают характерным блеском, хорошо проводят тепло и электричество.

Переходные металлы занимают группы 3—12 в периодической таблице. Большинство из них плотные, твердые, с хорошей электро- и теплопроводностью. Их валентные электроны (при помощи которых они соединяются с другими элементами) находятся в нескольких электронных оболочках.

3 группа побочная подгруппа (IIIB) шестого и седьмого периодов — лантаноиды и актиноиды.

Для удобства их помещают под основной таблицей.

- Лантаноиды иногда называют «редкоземельными элементами», поскольку они были обнаружены в небольшом количестве в составе редких минералов и не образуют собственных руд.

- Актиноиды имеют одно важное общее свойство — радиоактивность. Все они, кроме урана, практически не встречаются в природе и синтезируются искусственно.

Неметаллы

Правый верхний угол таблицы до инертных газов -неметаллы.

Неметаллы плохо проводят тепло и электричество и могут существовать в трёх агрегатных состояниях: твёрдом (как углерод или кремний), жидком (как бром) и газообразном (как кислород и азот). Водород может проявлять как металлические, так и неметаллические свойства, поэтому его относят как к первой, так и к седьмой группе.

Кислородные и водородные соединения

Все элементы, кроме гелия, неона и аргона, образуют кислородные соединения.

Существует 8 форм кислородных соединений: R2O, RO, R2O3, RO2, R2O5, RO3, R2O7, RO4,

где R — элемент группы.

Элементы главных подгрупп, начиная с IV группы, образуют газообразные водородные соединения. Существуют 4 формы водородных соединений: RH4, RH3, RH2, RH.

Характер соединений: RH — сильнокислый; RH2 — слабокислый; RH3 — слабоосновный; RH4 — нейтральный.

Опубликовано 3 года назад по предмету

Химия

от vetal86

где находится порядковый номер

-

Ответ

Ответ дан

Натаха228папиросимВ правом верхнем углу элемента

Самые новые вопросы

![]()

Математика — 3 года назад

Решите уравнения:

а) 15 4 ∕19 + x + 3 17∕19 = 21 2∕19;

б) 6,7x — 5,21 = 9,54

![]()

Информатика — 3 года назад

Помогите решить задачи на паскаль.1)

дан массив случайных чисел (количество элементов

вводите с клавиатуры). найти произведение всех элементов массива.2)

дан массив случайных чисел (количество элементов

вводите с клавиатуры). найти сумму четных элементов массива.3)

дан массив случайных чисел (количество элементов

вводите с клавиатуры). найти максимальный элемент массива.4)

дан массив случайных чисел (количество элементов

вводите с клавиатуры). найти максимальный элемент массива среди элементов,

кратных 3.

![]()

География — 3 года назад

Почему япония — лидер по выплавке стали?

![]()

Математика — 3 года назад

Чему равно: 1*(умножить)х? 0*х?

![]()

Русский язык — 3 года назад

В каком из предложений пропущена одна (только одна!) запятая?1.она снова умолкла, точно некий внутренний голос приказал ей замолчать и посмотрела в зал. 2.и он понял: вот что неожиданно пришло к нему, и теперь останется с ним, и уже никогда его не покинет. 3.и оба мы немножко удовлетворим свое любопытство.4.впрочем, он и сам только еле передвигал ноги, а тело его совсем застыло и было холодное, как камень. 5.по небу потянулись облака, и луна померкла.

Информация

Посетители, находящиеся в группе Гости, не могут оставлять комментарии к данной публикации.