1 сентября 2004 в североосетинском городе Беслане ничто не предвещало беды. Дети, сопровождаемые родителями, шли в школу. На торжественной линейке у средней школы №1 собралось несколько сотен человек. Внезапно на линейку ворвались вооруженные люди и начали загонять собравшихся в здание школы. Так началась Бесланская беда.

Захват

Первое сообщение о вооруженном нападении на школу поступило около половины десятого утра по московскому времени 1 сентября. Точных данных о количестве бандитов, равно как и о количестве захваченных ими в плен людей, не было. Известно было только, что бандиты подъехали к школе на машинах. В ходе перестрелки бандитов с милиционерами, охранявшими школу, последние были убиты. Часом позже министр по чрезвычайным ситуациям республики Борис Дзгоев подтвердил факт захвата школы. Во всех других школах Северной Осетии были отменены торжественные линейки.

.title ДОСЬЕ Vip.Lenta.Ru

Бесланская школа

Теракт на Рижской

Гибель самолетов Ту-134 и Ту-154

Как боевики добрались до Беслана? На этот счет пока точной информации нет. По рассказам одной из заложниц, террористы сами не знали, в каком городе они оказались. По рассказам тех, кто был в школе, боевики сказали, что гаишники продажные и что они заплатили милиционерам мало денег, в противном случае теракт был бы в более крупном городе (предположительно — Владикавказе). Но по другим данным, перед проведением операции террористы выбирали между несколькими учебными заведениями Северной Осетии. Выбор пал на школу №1 потому, что именно там учатся дети осетинской элиты. В частности, среди заложников оказались дети председателя парламента Северной Осетии, прокурора республики и некоторых других высокопоставленных чиновников.

Установлено, что боевики прибыли со стороны селения Хурикау Моздокского района Северной Осетии, которое находится в 30 километрах от административной границы с Ингушетией. Впервые появление боевиков было зафиксировано около восьми утра 1 сентября, за час до нападения на школу — между Малгобеком и Хурикау Моздокского района Северной Осетии. Там бандиты остановили машину участкового Солтана Гуражева и, отобрав у него оружие и документы, бросили милиционера в кузов грузовика. Боевиков интересовало служебное удостоверение участкового, которое помогло бы им в случае проверки сотрудниками ГИБДД. До Хурикау бандиты добрались по проселочным дорогам. В самом Хурикау террористы сняли с одной из попавшихся на дороге машин осетинские номера и переставили их на свою машину. К Беслану они направились объездной дорогой — мимо заброшенных хозяйств, где нет серьезных милицейских постов.

Представители ФСБ заявили позже, что боевики приехали в Беслан на двух машинах: грузовике ГАЗ-66 и «Газели». Оружие у боевиков было такое: крупнокалиберный пулемет Калашникова, автоматы с подствольными гранатометами, пистолеты, ручной противотанковый гранатомет, гранатометы «Муха», ручные гранаты, взрывчатка и боеприпасы. Все это вполне возможно привезти на двух машинах.

БОЙЦЫ СПЕЦПОДРАЗДЕЛЕНИЯ ВОЗЛЕ ЗАХВАЧЕННОЙ ШКОЛЫ. Фото Reuters.

Lenta.ru

По одной из версий, все свое вооружение боевики достали из грузовика, который после этого уехал. По другой — основная часть арсенала была спрятана в подвале школы заранее, когда боевики под видом рабочих вели там ремонт этим летом. Количества взрывчатки, по оценкам экспертов, хватило бы на то, чтобы заминировать едва ли не каждое помещение в школе. Сейчас следствие пытается выяснить, каким образом в подполе спортзала оказался склад с оружием. По словам заложников, террористы заставляли старшеклассников отдирать доски от пола и подавать им боеприпасы.

Вооружены боевики были отлично. Трое суток террористы обстреливали окрестности школы. Позже, когда начался штурм, они очень долго и упорно сопротивлялись. Почему правоохранительные органы не знали об этом и почему через все блокпосты пропустили в город колонну боевиков — об этом можно судить только по слухам. К тому же накануне праздничной линейки здание школы милиционеры проверяли и ничего не нашли.

После подтверждения информации о захвате школы, по тревоге было поднято антитеррористическое спецподразделение ФСБ — группа «А» («Альфа»). В Беслан вылетели как сотрудники отряда, дислоцированные в Ханкале, так и московское отделение «Альфы».

Осада

Большую часть заложников бандиты согнали в спортзал. В спортзале всех посадили на пол. Отдельные террористы сразу сняли маски, кто-то масок не снимал все три дня. У женщин были пояса шахидок, кнопки от которых они держали в руках.

Нас погнали в школу в спортзал. Дверь в зал была заперта. Люди в масках выбили окна, запрыгнули в них и с той стороны выбили двери в зал. Затем, уже в зале, приказали нам сесть на пол и начали быстро минировать зал. Две большие взрывчатки они положили в баскетбольные корзины, затем через весь зал протащили провода, к которым привязали взрывчатки поменьше. В течение десяти минут весь спортзал был заминирован.

Мужчин сразу же заставили работать: ломать двери, приносить из расположенных рядом кабинетов парты и делать баррикады. Других мужчин заставили заниматься развешиванием бомб в спортзале. Бомбы находились в пластиковых бутылках из-под газировки, начиненных взрывчаткой, гвоздями и шурупами. Часть бомб была подвешена над головами заложников, часть была расставлена вдоль стен. Все бомбы были соединены друг с другом, а пульт управления находился на полу. У пульта, сменяя друг друга, дежурил кто-то из боевиков.

В туалет заложникам запретили ходить на второй день — там в кране была вода, и некоторые ее пили. Но большинству даже в первый день не удалось выпить ни глотка воды. Дети пили собственную мочу. В спортзале вскрыли полы, чтобы никого никуда не выводить — в туалет надо было ходить прямо в эту яму.

Женщин с маленькими детьми посадили в школьную столовую. После возведения баррикад террористы решили избавиться от всех мужчин, которые, как они подозревали, могли оказать сопротивление. В результате 1-го и 2-го сентября террористы отвели в один из кабинетов на втором этаже школы 20 человек, которых расстреляли, а тела выбросили в окно.

Все три дня, пока мы там сидели, мы сидели чуть ли не друг на друге. Нас там было около 1100 человек. Время от времени заходили боевики и ради смеха приказывали то стоять всем, то лежать. И так продолжалось почти целыми днями. В центре они установили большое взрывное устройство, примерно 50×50 см, пульт от которого был нажимного действия. Его постоянно прижимал ногой кто-то из террористов. Когда они уставали, на кнопку ставили стопку книг.

Бывшая заложница Марина Козырева

Нескольким детям удалось выбраться из захваченного здания. Они сообщили, что бандитов около 20 человек, все одеты в черное, на лицах — маски. На многих из них были надеты пояса шахидов, они были вооружены гранатометами и стрелковым оружием.

Территория вокруг школы была оцеплена, и к району происшествия стянулись силы ОМОНа, СОБРа, подразделения внутренних войск, милиция, армейские подразделения и несколько машин «Скорой помощи». В течение первых часов после захвата террористы отказывались вступать в переговоры и выдвигать какие-либо требования. Около полудня террористы, захватившие школу, передали записку, в которой угрожали взорвать здание в случае начала штурма, а позже с одним из отпущенных заложников передали правоохранительным органам записку с одним-единственным словом: «Ждите». Кроме того, бандиты потребовали, чтобы к ним прибыли президент республики Александр Дзасохов, глава Ингушетии Мурат Зязиков и детский врач Леонид Рошаль.

Примерно в час дня 1 сентября в районе захваченной школы началась стрельба. В районе улицы Калинина раздалось три взрыва — под прикрытием БТР военные попытались вынести тела убитых и раненых, но боевики открыли по ним огонь из автоматов и гранатометов.

1 сентября, по прилете в Москву из Сочи, президент РФ Владимир Путин провел в аэропорту совещание с участием руководителей силовых ведомств. В Северную Осетию прибыли глава МВД РФ Рашид Нургалиев и руководитель ФСБ Николай Патрушев. Позже в Беслан прибыл доктор Леонид Рошаль, участие которого в переговорах требовали террористы.

Пить не позволяли. И есть не давали. Они совсем обозлились. Когда нас отпускали в туалет, то некоторые дети забегали в разломанный кабинет, который недалеко от туалета. Там стояли в горшках цветы. Так вот, они цветы эти рвали и запихивали в рот. Некоторые прятали цветы в трусах и делились с товарищами. Но голод не так мучил, как жажда. Некоторые дети не выдерживали, мочились себе на ладони и пили.

Бывшая заложница Диана Гаджинова

Вскоре после этого террористы выдвинули первые требования: освободить боевиков, принимавших участие в нападении на Назрань ночью 22 июня. От предложения обменять школьников на двух высокопоставленных осетинских чиновников боевики отказались. Зато прибавили к первоначальному требованию еще одно — вывести федеральные войска из Чечни. За каждого убитого боевика террористы пригрозили расстреливать по 50 детей, за каждого раненого — по 20. Террористы отказались от переговоров с муфтием Русланом Валгасовым и прокурором Беслана Аланом Батаговым. Предложение властей республики о предоставлении им коридора до Ингушетии и Чечни, а также о замене детей на взрослых, бандиты не приняли. Во время переговоров с Аушевым боевики выдвинули свое последнее требование — предоставить Чечне независимость.

После переговоров с Аушевым террористы освободили группу заложников — 26 женщин и детей. Большинство освобожденных сразу же отправили в больницу. По словам Рошаля, угрозы жизни детей, захваченных в заложники в Северной Осетии, на тот момент не было — по словам детского врача, заложники могли продержаться без пищи и воды восемь-девять дней.

1 сентября в школе произошло первое серьезное ЧП. Две женщины-смертницы зашли в столовую, после чего отправились в спортзал. Тут на одной из смертниц сработала бомба. Поскольку женщина находилась далеко от заложников, а бомба была компактной, никто, кроме самой террористки, не погиб.

Все это время официальные лица не приводили никаких точных данных — ни о числе боевиков, ни о количестве заложников. Цифры назывались самые разные, но точка зрения властей была следующей: в школе находится около 300 заложников, удерживаемых 20-25 бандитами.

Штурм

Около трех часов утра в пятницу, 3 сентября, перед родственниками заложников в зале бесланского Дома культуры выступил врач Леонид Рошаль, который сообщил, что находится в контакте с террористами. Именно он впервые озвучил реальные масштабы происшествия: в захваченной школе находится не 300 заложников, как говорилось вначале, а более тысячи. Президент Северной Осетии Александр Дзасохов пообещал, что штурма не будет ни при каких обстоятельствах, а боевики рано или поздно устанут, потребуют автобусы и их переправят в любое требуемое место. В штабе операции в тот момент не помышляли о силовой акции, рассчитывая еще какое-то время вести переговоры.

СОТРУДНИКИ СПЕЦСЛУЖБ ШТУРМУЮТ ЗДАНИЕ ШКОЛЫ. Фото Reuters.

Lenta.ru

Естественно, различные варианты штурма подразделения спецназа разрабатывали, но только теоретически, поскольку в подобных ситуациях так поступают любые антитеррористические группы.

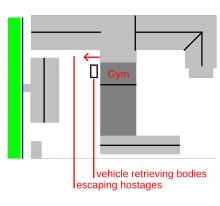

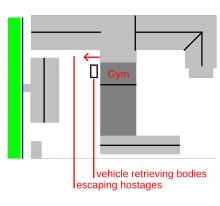

К полудню 3 сентября боевики разрешили забрать из-под окон здания трупы убитых ранее заложников. Около часа дня к школе подъехал грузовой «ЗиЛ» с четырьмя сотрудниками МЧС. Они должны были забрать трупы со школьного двора. Все три дня бандиты расстреливали заложников, в первую очередь мужчин, и трупы начали разлагаться.

Боевики гарантировали спасателям безопасность. По крайней мере, так заявили представители спецслужб, отправлявшие грузовик. Что именно произошло в тот момент, когда сотрудники МЧС заехали на автомашине во двор школы, до сих пор неизвестно. Неожиданно раздалось два взрыва, а следом загрохотали автоматные очереди. Сначала никто не понял, что происходит.

По одной из версий, в этот момент по какой-то причине в толпе заложников взорвалась самодельная бомба, и у боевиков не выдержали нервы — они начали стрелять по людям. В результате возникшей паники заложники попытались вырваться наружу и смяли охрану. По другой — когда подъехали сотрудники МЧС и взорвался снаряд, боевики решили, что начался штурм и открыли огонь. В самом спортивном зале охрана после взрыва растерялась, все заволокло пылью и дымом, и люди начали выпрыгивать в окна.

То, что говорят, что это был взрыв снаружи, это все неправда, потому что я сам видел, как взорвалась взрывчатка, которая была приклеена на скотче. До того как она взорвалась, я сидел прямо под ней, но перед этим отошел в сторону, а потом, после того как она взорвалась, я посмотрел на людей, и все, кто сидел тогда рядом со мной, они погибли.

Бывший заложник Марат Хамаев

По словам одного из заложников, все началось с того, что бомба или сработала самопроизвольно, или скотч, на котором она болталась на баскетбольной корзине, просто отклеилась. Сразу после первого взрыва произошел второй — одно из взрывных устройств террористы установили таким образом, что кнопку запала нужно было держать ногой. В течение двух предыдущих суток террористы каждый час сдавали смену, и никто не отпускал свою ногу до тех пор, пока на кнопку не наступал его сменщик. По словам выживших, когда произошел первый взрыв, «дежурный» террорист отпустил кнопку.

По-видимому, основная масса людей погибла именно в результате первых взрывов. Здание спортзала было практически разрушено. Родители начали выбрасывать своих детей в разбитые окна. Кругом лежали трупы. Потом дети сами ринулись в проломы, причем взрослые порой отталкивали детей, чтобы первыми выскочить на улицу. Некоторые террористы, схватив детей и прикрываясь ими, начали стрелять в спины убегающим. Стреляли без разбора: в детей, во взрослых и в оцепление.

После взрывов с территории школы, со стороны внутреннего двора, на который выходят окна спортзала, начали выбегать первые дети. Тут же к зданию ринулись бойцы различных подразделений и местные вооруженные жители-ополченцы, которые с первого дня дежурили вокруг школы.

Стремительное развитие событий вокруг школы стало полной неожиданностью для всех — руководителей оперативного штаба, членов входившей в него группы «переговорщиков», поддерживавших контакт с террористами, а также бойцов спецподразделений. В результате в первые полчаса в районе школы царил полный хаос. Оперативный штаб был в такой растерянности, что не мог организовать даже доставку раненых в больницы — их развозили местные жители на своих машинах.

Когда раздался взрыв, дети и взрослые бросились к окнам. И боевики открыли по ним беспорядочный огонь из автоматов. Даже после того, как основная масса людей выбежала из спортзала, они, уходя в подвал школы, продолжали расстреливать лежащих на полу спортзала людей.

Бывшая заложница Алла Гадзиева

Огонь велся как из школы, так и по школе — стреляли армейцы и милиционеры вперемешку с ополченцами. В ответ боевики поливали штурмующих огнем с крыши и из окон второго этажа. Все это время из школы на улицу продолжали выбегать сотни окровавленных детей и взрослых. Под непрерывный треск автоматов и разрывы гранат к школьному двору навстречу им бежали спасатели, пожарные и просто местные жители, пробравшиеся через оцепление, чтобы принять из окон обезумевших детей, вынести раненых и увести тех, кто сам не понимал, куда бежать. Не хватало ни носилок, ни врачей, ни «Скорых».

Заложники разбегались во все стороны, все в нижнем белье, окровавленные и плачущие. От каждого шел сильный запах экскрементов — все три дня бандиты никому не позволяли выйти в туалет, заставляя ходить «под себя». У многих в волосах налипла кровь — останки убитых в результате первых взрывов.

Таким образом, операция с самого начала вышла из-под контроля и начала развиваться спонтанно. Кто первым открыл огонь по школе, наверное, никогда никто не узнает. Уже через несколько секунд после взрывов в спортзале застрочил пулемет, потом подключились автоматы, подствольные гранатометы, снайперские винтовки. Начался бой, причем огонь велся со всех сторон школы.

ОПОЛЧЕНЦЫ ВЫНОСЯТ ЗАЛОЖНИКОВ С ПОЛЯ БОЯ. Фото Reuters.

Lenta.ru

Есть мнение, что первыми по боевикам начали стрелять милиционеры и солдаты внутренних войск из оцепления. Оперативный штаб сначала приказал прекратить огонь, а потом на некоторое время вообще перестал издавать приказы. В это время часть боевиков, видимо, согласно заранее намеченному плану, пошла на прорыв. На помощь милиции подошел спецназ 58-й армии. Его бойцы попытались блокировать боевиков, которые с оружием в руках прорывались из школы. Они же первыми дошли до стены спортзала и начали вытаскивать людей.

К моменту вынужденной атаки школы бойцы групп «Альфа» и «Вымпел» еще не распределили между собой «секторы» ответственности по периметру школы, огневые точки террористов, не рассчитали маршруты подхода к зданию, способы передвижения внутри и так далее. Все это находилось в стадии обсуждения на случай штурма, так как в тот момент штурм еще не входил в ближайшие планы оперативного штаба. Поэтому действовать пришлось без согласованной схемы. Бойцы спецподразделений потеряли свой главный козырь — внезапность — и вынуждены были действовать, как простые пехотинцы.

Только через 30 минут после первого взрыва «Альфа» предприняла первую по-настоящему серьезную атаку здания и смогла проникнуть внутрь школы. Для того чтобы попасть в спортзал, штурмующие сделали пролом, взорвав стену. В зале находилось множество убитых, раненых и просто перепуганых людей. Боевиков там уже не было. Первыми внутрь вошли саперы 58-й армии, так как кругом были мины, а под потолком была развешена целая взрывная сеть. Саперы прошли через зал, сняв часть взрывчатки, но при переходе в здание школы попали под огонь из соседнего крыла.

Через некоторое время после прорыва заложников, бойцы «Альфы» и «Вымпела», штурмуя школу, начали выискивать места, откуда стреляют террористы. Спецназовцы пытались подавить огневые точки бандитов и прикрыть своим огнем спасающихся заложников. Одновременно они и сами выносили на руках раненых, тем самым подставляясь под пули боевиков.

Так, когда один из бойцов нес двух девочек, пуля снайпера попала ему в шею. Действия «Альфы» и «Вымпела» осложнялись еще и тем, что у боевиков было время, чтобы освоиться и выбрать наиболее удобные точки для обстрела. По мнению сотрудников ФСБ, террористы к моменту начала боя получили огневую поддержку из соседнего здания. По версии оперативников, снайперы засели там еще до того, как в спортзале раздался взрыв.

Неофициально сотрудники «Альфы» в субботу подтвердили, что события в Беслане уже могут считаться самыми тяжелыми в истории подразделения. При штурме здания школы и спасении заложников погибли три бойца «Альфы» и семь бойцов «Вымпела». Ранения, по разным данным, получили от 26 до 31 спецназовца. За всю историю существования групп «Альфа» и «Вымпел» это были самые крупные потери.

Из-за того, что местное ополчение стояло на всех подступах к школе, штурм превратился в городской бой. Бойцам спецназа приходилось бежать к школе между местными ополченцами, которые бросились к спортзалу, чтобы вынести детей. Так как штурм начался неожиданно для всех, многие из спецназовцев были без бронежилетов. В результате всех этих причин спецназ понес столь значительные потери.

Освобождение заложников растянулось на десять с лишним часов, и уничтожить всех боевиков удалось только к половине двенадцатого ночи. Главная причина этого заключалась в том, что бандиты прикрывались заложниками, оставшимися в живых после взрыва и обрушения потолка в спортзале.

Спустя непродолжительное время после начала операции стало ясно, что часть боевиков вышла из оцепления и ведет бой с военными в городе. Уже в самом начале штурма террористы разделились на несколько групп. Часть из них захватила с собой несколько десятков заложников, спустившись в подвальное помещение. Вторая группа обеспечивала отвлекающий маневр. Боевики смогли вырваться из школы в южном направлении. Им удалось прорваться из здания школы и занять оборону в одном из близлежащих домов.

ВСЕ, ЧТО ОСТАЛОСЬ ОТ СПОРТЗАЛА БЕСЛАНСКОЙ ШКОЛЫ №1. Фото Reuters.

Lenta.ru

Ожесточенные бои шли как в самом здании школы, так и в расположенном неподалеку пятиэтажном жилом доме. Несколько залпов по этому дому произвели танки. В основном с террористами вел перестрелку спецназ ФСБ, ополченцы же проверяли дворы и выискивали на улицах подозрительных людей.

Дом, в котором укрепились боевики, находился в 50 метрах от школы, рядом с базаром. Поскольку он стоял в зоне оцепления, все его жильцы были эвакуированы еще 1 сентября, и дом тут же был блокирован федералами. Боевики заняли серьезную оборону, и их не могли выбить оттуда как минимум до 5 часов вечера.

Внутренние войска и местный ОМОН начали прочесывать улицы в районе вокзала, примерно в полукилометре от школы. До позднего вечера в городе шла стрельба. Бойцы спецподразделений выбивали из подвала последних боевиков, которые прикрывались заложниками. Перестрелки со сбежавшими боевиками велись и в других частях города. Лишь к ночи Беслан был зачищен.

Днем 5 сентября власти Северной Осетии обнародовали уточненные данные о количестве жертв теракта в Беслане. Убитыми были названы 335 человек. Как сообщил журналистам руководитель информационно-аналитического отдела при президенте Северной Осетии Лев Дзугаев, общее число погибших в школе, по данным на 14:30 по московскому времени, составляло 323 человека, в том числе 156 детей. Всего, по данным Дзугаева, помощь медиков понадобилась 700 пострадавшим.

Сергей Карамаев

3 сентября 2004 года закончились трагические события в Беслане

1 сентября вся наша страна отмечает замечательный праздник – День знаний. Тысячи нарядно одетых мальчиков и девочек отправляются в школы, чтобы окунуться в волшебный мир знаний. Это всенародный праздник. Правда, этот праздник обернулся кровавой трагедией для жителей города Беслана в Северной Осетии 1 сентября 2004 года, когда группа чеченских боевиков провела подлую террористическую акцию, погубившая сотни мирных людей.

Смена тактики

В феврале 2000 года формально закончилась 2-я чеченская война. Этому способствовало то, что федеральные войска заметно улучшили свою подготовку и на сторону армии перешел муфтий Ичкерии Ахмат Кадыров, который осудил ваххабизм и выступил против боевиков Масхадова. В ноябре 1999 года федеральные войска подошли к Грозному. 6 февраля после длительных боев от бандитов был освобожден Грозный, но боевые действия на этом не закончились: часть боевиков смогла вырваться из города и начала партизанскую войну. Силы боевиков были подорваны, и постепенно их активность снизилась. Многие восприняли ситуацию с надеждой, что чеченский конфликт пошел на спад. Действительно, медленно, но верно федеральные власти продолжали выбивать отряды террористов, к этому времени многие военные вожди Ичкерии погибли или попали в плен, да и в самой Чечне медленно, но налаживалась мирная жизнь. Действующая практика амнистий также нарушила целостность подполья и боевых отрядов. К этому времени практически иссяк поток желающих пополнить ряды бандитских отрядов, а многие боевики просто сдавали оружие или уезжали за границу.

Главари сепаратистов понимали, что пройдет еще немного времени и их формирования будут полностью разгромлены. В этих условиях они стали менять не только тактику, но и весь стиль войны. Была предпринята попытка вывести военные действия за пределы Чечни. Свои военные усилия они сосредотачивают у своих соседей – в Дагестане, Ингушетии и Кабардино-Балкарии. Вторым элементом новой стратегии становится террор. Они запомнили, какой эффект произвел теракт в Буденновске и постарались объединить отдельные акты до полноценной кампании.

Наиболее активным стал 2004 год. Дважды были проведены акции в московском метро, 22 августа бандиты напали на Ингушетию, а затем были взорваны два пассажирских самолета. Но этого им казалось мало. Нужен был такой теракт, чтобы вся страна содрогнулась, чтобы вызвал паралич воли.

Бесланская трагедия

Боевики долго не мучили себя поисками подходящего объекта для атаки. Школа, с точки зрения террористов, самый подходящий объект. Дети не могут сопротивляться, а психологический эффект может превзойти все ожидания. Школа в Беслане – очень подходящий вариант, так как между ингушами была напряженность из-за приграничных вооруженных конфликтов. В состав нападавших было включено большое количество ингушей, а объектом выбрали осетинскую школу. Сразу скажу, что из всех нападавших выжил только один человек. Когда его спросили, зачем, он ответил: «Чтобы развязать большую войну на Кавказе». Сегодня из средств массовой информации мы узнаем об успешной работе спецслужб по предотвращению терактов, а в то время у властей практически никаких данных об этом не было. Только 31 августа появились смутные сведения о подготовке нападения на школу. Где, когда и кто – такими данными власть не располагала. Но и минимальные данные не были приняты во внимание.

Банду нападавших сформировали из опытных боевиков, неоднократно попадавших в поле зрения милиции, а сам главарь банды Руслан Хучбаров разыскивался за убийство. Всего в банду входило 32 человека.

Рано утром 1 сентября грузовик ГАЗ-66, полный бандитов, подъехал к школе №1 города Беслана. Только начавшаяся праздничная линейка была прервана автоматными очередями. Сразу был убит один из родителей, что продемонстрировало серьезность намерений бандитов. Всех, кто был на площади, а это родители, учителя и школьники, загнали в спортзал. В этом маленьком помещении оказалось 1128 человек. Спортивный зал был превращен в одну большую самодельную мину, которую боевики готовы был взорвать в любую минуту.

Попытку освободить школьников предприняли милиционеры из соседнего отделения милиции, но сделать уже ничего не могли. В перестрелке был убит один из боевиков.

Террористы выставили свои требования. Одно из них – не отключать связь и свет, иначе они откроют огонь, а второе – политическое требование Басаева о признании Ичкерии. Школа была превращена в крепость, мужчин из числа заложников, которых они заставили баррикадировать здание, позже расстреляли, а тела выкинули в окна.

Что делать?

Оперативный штаб был сформирован, но, что делать в такой ситуации, никто не знал. Начали составлять списки людей, оказавшихся в заложниках у бандитов. В город стали стягивать войска, в том числе и подразделения «А» и «Б». Близко подойти к школе было нельзя, оттуда стреляли по всему, что движется. На другой день бандиты разрешили вывести 24 заложниц с грудными детьми, поскольку те кричали, не понимая угроз. Вывел их президент Ингушетии Руслан Аушев. То, что вывели маленьких детей, обстановку в школе не улучшило. Все заложники сидели на сухой голодовке, в туалеты никого не пускали, и школа превратилась в грязевую яму.

Вокруг школы суетились местные ополченцы. Они были вооружены различным оружием, оставшимся от военных конфликтов 90-х годов. Помощи от них не было никакой, а сумятицу они вносили значительную. Местное отделение ФСБ пыталось найти выход из положения, но не находило. Хучбаров требовал, чтобы велись переговоры с Масхадовым, но тот не выходил на связь.

На третий день обстановка стала критической. Из-за обезвоживания заложники обессилели, падали в обмороки, должны были появиться первые погибшие. Основные силы «Альфы» и «Вымпела» готовились к штурму. Все понимали, что штурм принесет огромные жертвы, а тянуть дальше тоже больше было нельзя. Судьбу всех решили случайные обстоятельства.

Непредвиденный штурм

Такими обстоятельствами стали спасатели МЧС. По договоренности с бандитами они подъехали для уборки трупов, выброшенных из окон. В то время, когда спасатели грузили тела, внутри здания произошли два взрыва. Самодельные взрывные устройства имеют недостаток – они ненадежны, потому взорвались они, по всей видимости, случайно. Эти взрывы убили и ранили сотни людей. Все, кто мог ходить, ринулись из здания. Боевики открыли по ним шквальный огонь.

Одновременно к школе бросились местные ополченцы, пытавшиеся стрелять по бандитам, но этим только усилили хаос. К сожалению, основные силы спецподразделений были в отдалении, пока они подоспели, прошло время. Через несколько минут после начала бойни начался пожар, который еще больше усугубил положение. Прибывшие бойцы «Альфы» и «Вымпела» взяли всю операцию на себя. Офицеры были скованы толпами заложников, а бандиты стреляли веером во все живое. Многие заложники говорили, что часть офицеров погибла, защищая людей, прикрывая гранаты своими телами. За время этого боя оставшиеся дети были выведены из горящего здания. После этого бой с бандитами продолжился, в живых остался только один террорист Нурпаша Кулаев, который выскочил из здания после первых взрывов через окно, но был задержан и в дальнейшем был приговорен к пожизненному заключению.

Результат этой бойни ужасает: в Беслане погибло 334 человека, включая 186 детей, десять офицеров и девять человек из спасательной службы и МВД. Был убит 31 террорист. Басаеву удалось организовать практически идеальное убийство, и жертвами его стали дети. Результат этой кровавой бойни не принес ожидаемого успеха бандитам. Война не получила дополнительной подпитки, как они ожидали. Руины школы в Беслане так и остаются самым жутким памятником человеческой жестокости со времен Великой Отечественной войны. Беслан не принес никаких политических дивидендов Басаеву и Масхадову. Он только ускорил их движение к бесславной гибели.

P.S.

3 сентября в нашей стране отмечается День солидарности в борьбе с терроризмом. Дата установлена в память о трагических событиях в Беслане 2004 года. К сожалению, одной солидарности мало. Нужно, чтобы борьба с терроризмом стала для всех общественно-политической задачей номер один. Многие страны понимают, какие масштабы приобретает эта зараза в наше время, и они готовы с этим бороться, а многим кажется, что все эти события проходят далеко от их дома, что удел слабых и неразвитых стран. Но беда дает о себе знать и в благополучной Европе, и в далекой Америке. Взрывы гремят на французской и немецкой землях, толпы бывших экстремистов гуляют по площадям Лондона и Брюсселя. Где выход из положения? Ну попробовали американцы побороться с терроризмом на его родине – в Афганистане. Начав операцию «Несокрушимая свобода» в ответ на террористические атаки 11 сентября 2001 года, они 20 лет искореняли терроризм, создали огромную армию, вложили сотни миллиардов долларов, потеряли тысячи своих солдат и ушли. Ушли, оставив созданные базы тем самым террористам, попутно вооружив их самым современным оружием. Оказалось, что не террористы были главной задачей, а экономические и политические интересы великой державы. Победить терроризм нельзя, если выступать с позиций двойных стандартов. Нет хороших террористов, нет умеренных террористов – они все одной крови. И если не будет коллективных усилий большинства государств и народов, эта проблема так и останется кровоточащей раной. Мы его не уничтожим – он уничтожит нас.

18 лет назад, в 2004 году, террористический отряд захватил среднюю школу №1 в Беслане в республике Северная Осетия. В заложниках оказались более тысячи человек. В результате теракта погибли 333 человека, среди которых 186 детей от года до 17 лет. Медицинскую помощь оказали более 800 выжившим. Что происходило в бесланской школе с первого по третье сентября и почему эта трагедия приняла такой масштабный оборот, рассказывает ivbg.ru.

Как День знаний превратился в трехдневных кровавый парад?

Тем роковым утром, 1 сентября 2004 года, торжественная линейка в честь Дня знаний в бесланской средней общеобразовательной школы №1 республики Северная Осетия-Алания внезапно закончилась из-за автоматных выстрелов. Вооруженные террористы из 32 человек под предводительством Руслана Хучбарова загнали большинство участников мероприятия — детей, родителей и преподавательский состав — в спортивный зал школы, который сразу же нашпиговали самодельными взрывными устройствами, подключенными к взрывной цепи. Других заложников поместили в тренажерном зале и душевых.

Для запугивания заложников было расстреляно несколько человек. Бандиты предупредили, что за смерть одного из их товарищей будет убито 50 человек, а за ранение — 20.

Как бандиты были вооружены?

На момент захвата школы головорезы имели при себе противогазы, аптечки и запас провизии на несколько дней. Военное снаряжение было следующим: около 22 автоматов Калашникова различной модификации, в том числе и с подствольными гранатометами, пара ручных пулеметов РПК-74, два пулемета ПКМ, танковый пулемет Калашникова, несколько ручных противотанковых гранатометов РПГ-7 и гранатометы РПГ-18 «Муха».

Чего боевики пытались добиться?

День первый — 1 сентября

Изначально никаких требований они не выдвигали. В первый день заключения заложникам разрешалось ходить в туалет и пить воду из мусорных ведер, но на всех ее не хватало. После полудня захватчики передали записку, где пояснили, что в случае штурма взорвут здание школы. Чуть позже они отпустили заложника, который передал письменное послание, гласившее: «Ждите». Во второй половине дня случилось непредвиденное — подорвалась террористка с поясом шахидов. В результате этого боевики расстреляли 20 человек. Боясь бунта, они избавились от всех мужчин, устроив массовый расстрел на втором этаже, и скинув трупы из окон во внутренний двор.

Первым условием головорезов стал вызов на переговоры представителей власти: главы Ингушетии Мурата Зязикова, президента Северной Осетии Александра Дзасохова, а также экс-секретаря Совбеза России Владимира Рушайло. По другой информации, третьим лицом, которого желали видеть боевики в стенах школы, являлся директор НИИ медицины катастроф доктор Леонид Рошаль, который прибыл на место происшествия.

День второй — 2 сентября

Во второй день осени того года террористы позволили бывшему главе Ингушетии Руслану Аушеву войти в здание. Он договорился с головорезами, чтобы те отпустили 26 человек — женщин с малолетними детьми. Боевики в переговорах с экс-президентом выдвинули следующие требования: освободить террористов, принимавших участие в нападении на Назрань ночью 22 июня, а также вывести федеральные войска с территории Чечни. Согласно многим источникам, последним условием стало предоставление Чечне независимости, но эта информация официально не подтверждалась.

На тот момент прошли уже сутки с момента захвата. Заложники ослабли и пережитый стресс сказывался на общем состоянии. После общения с Аушевым головорезы озлобились. Перестали давать воду и запрещали спать. Прямо в зале спортзала отодрали от пола доски, организовав таким образом яму для экскрементов. Ей позволяли пользоваться по своему усмотрению.

«Призывали к соблюдению дисциплины они нас словами: «Руки зайчиком!». В таком положении руки очень затекали», — рассказывала бывшая заложница, на тот момент ученица девятого класса Агунда Ватаева.

Для утоления жажды захваченные террористами люди были вынуждены пить собственную мочу. Многие не выдерживали и падали в обморок. Среди них находились диабетики, что осложняло ситуацию.

Все три дня боевики отказывались от замены детей на взрослых и денежного вознаграждения за освобождение заложников, а также от передачи людям необходимых лекарств, воды и продуктов.

День третий — развязка

По словам Агунды Ватаевой, которая потеряла маму при таких страшных обстоятельствах, на третий день все заложники хотели, чтобы ситуация разрешилась. И было уже не важно каким образом. Главное, чтобы все кончилось. Люди хотели спать и валились от усталости и стресса, а боевики угрожали, что будут расстреливать тех, кто потерял сознание.

Около часа дня к зданию школы подъехала машина с четырьмя спасателями, которые, согласно договоренности с террористами, должны были увести трупы с территории двора. В это момент в школьном спортивном зале случилось два мощных взрыва, из-за которых стены здания частично разрушились и заложники кинулись наружу. Матери выбрасывали своих детей из разбитых окон. Завидев выбегающих школьников, специалисты всех подразделений и местные жители-ополченцы, дежурившие возле школьной территории с первого дня захвата, двинулись в наступление. Боевики, оценив обстановку, начали беспорядочную стрельбу. Стреляли в спины убегающих заложников и начали отходить, прикрываясь попавшими под руку детьми. Бандиты переместились вместе с оставшимися заложниками в актовый зал и столовую, из которой продолжили отстреливать сбежавших заложников. Тех, кто не мог передвигаться самостоятельно, головорезы добивали с помощью автоматов. В руках боевиков оставались около двухсот человек.

Операция по спасению заложников и ликвидации боевиков

Оперативный штаб, организованный в связи с чрезвычайной ситуацией, занимался разработкой плана по освобождению заложников. Его участники не были готовы к подобному повороту событий. После взрыва представители штаба попробовали наладить с террористами контакт и еще раз попросили освободить заложников. Глава шайки прервал переговоры и разбил средство связи, отдав приказ «отстреливаться до последнего».

В первые полчаса после взрыва на территории школы творился жуткий хаос: выбегающие окровавленные дети и взрослые, полностью дезориентированные и находящиеся в шоковом состоянии люди, попытки спецслужб пробраться в здание и остановить поток огня со стороны боевиков, ожесточенное сопротивление террористов, которые за три дня продумали запасные огневые позиции на случай штурма. Сотрудники милиции, спасатели и обычные люди пытались помочь выбравшимся уйти с опасной местности. Террористы кидались сверху гранатами, что приводило к новым жертвам и мешало спасательной операции. «Скорые» не справлялись с потоком пострадавших, поэтому местные жители сооружали самодельные переноски для тяжелораненых и перевозили их на личным транспорте в ближайшие больницы.

В операции по освобождению заложников и зачистке террористов участвовали бойцы ЦНС ФСБ из спецподразделений «Альфа» и «Вымпел», гражданские спасатели и сотрудники МЧС и МВД. На это ушло более 10 часов. Учитывая непредвиденные обстоятельства и отсутствие продуманной схемы действий, штурм превратился в городской бой. Ополченцы и сотрудники МЧС окружили здание со всех сторон и вытаскивали детей. Между ними сновали спецназовцы, проникая в здание с трех разных направлений. В экстремальной ситуации некоторые члены спецподразделения оказались без бронежилетов, а плохая видимость после взрыва и ожесточенный отпор террористов сказались на числе пострадавших. Три бойца «Альфы» и семь бойцов «Вымпела» погибли при исполнении миссии, четверым из них присвоены звания Героев России. Около 30 спецназовцев получили ранения. Также погибли шесть гражданских спасателей и один сотрудник МВД.

Итоги трагедии в Беслане

Говоря о Беслане, даже люди, не принимавшие никакого участия в событии, испытывают ужас от произошедшего. Жертвами теракта стали 333 человека, из которых 186 — дети от одного года до 17 лет. Та роковая линейка перевернула жизнь не только заложников, но и их близких, а также всех участников рокового события. Многие потеряли родных, некоторые дети стали сиротами.

По делу о нападении террористов на школу в Беслане потерпевшими признали 1315 человек.

Согласно данным Генпрокуратуры, в бандитской группировке, напавшей на школу, было 32 человека, в числе которых было две смертницы, подорвавшихся до спасательной операции. Во время штурма спецназовцам удалось задержать одного из преступников — Нурпаши Кулаева, остальные были ликвидированы. Судебные разбирательства в отношении боевика начались в мае 2005 года. Куваев обвинялся в бандитизме, терроризме, убийстве, посягательстве на жизнь сотрудника правоохранительных органов, захвате заложников, незаконном хранении, ношении, приобретении оружия, боеприпасов и взрывчатых веществ. Через год Верховный суд Северной Осетии признал террориста виновным по всем статьям предъявленных ему обвинений и приговорил к пожизненному заключению.

Теракт в Беслане называют самым бесчеловечным преступлением, совершенным на территории современной России.

Теперь 3 сентября – памятная дата в российском календаре. В этот день россияне вспоминают жертв террористической атаки на Беслан и склоняют головы в память о всех жертвах террористической агрессии, с которой когда-либо сталкивался наш народ. День солидарности в борьбе с терроризмом появился в календаре памятных и скорбных дат РФ на основании федерального закона от 21 июля 2005 года.

Начиная с 2005 года, в Северной Осетии каждый год с первого по третье сентября включительно проходят траурные мероприятия, которые посвящены памяти погибших при теракте в бесланской школе. В эти несколько дней люди покрывают цветами мемориальный комплекс, открытый на месте разрушенного здания, и кладбище «Город ангелов», где захоронена основная часть погибших заложников. Там же в 2005 году открыли памятник «Древо скорби», а через год воздвигли мемориал бойцам спецназа и спасателям МЧС, которые погибли в процессе освобождения заложников. В Беслане из-за траура начало учебного года сдвигается на четвертое сентября.

Где хранится память о жертвах теракта в Беслане?

Во дворе школы, которая осталась в том же виде, как и после трагедии, возвели Храм Бесланских младенцев на пожертвования жителей Осетии и благотворителей из различных регионов страны.

Памятники жертвам Беслана также были установлены во Владикавказе, Санкт-Петербурге, в центре Москвы, в селе Коста-Хетагурова Карачаево-Черкесии и во Флоренции в Италии. В 2015 году одна из центральных улиц итальянской коммуны Кампо Сан Мартино была названа Улицей Детей Беслана.

Главная память о жертвах трагедии — в наших сердцах. Помним, любим, скорбим…

В 2004 году День знаний в североосетинском Беслане стал днём трагедии для всей России. Школу №1 захватили террористы. В заложниках оказались 1128 мирных жителей – все они пришли на праздник в честь начала учебного года. Для трёх сотен человек это 1 сентября стало последним.

Тщательная подготовка

Террористы готовились к атаке ещё летом. Здание школы №1 в Беслане боевики выбрали по ряду причин. Во-первых, там училось много детей. Во-вторых, расположение города относительно границы с Ингушетией играло на руку захватчикам – от лагеря, где они базировались, до школы было всего 30 километров. Устраивала бандгруппу и конфигурация корпусов школы – к строению, возведённому ещё в 1889 году, за сотню лет неоднократно пристраивали новые помещения, что сделало здание весьма запутанным и дало возможность террористам придумать себе удобные пути отступления небольшими группами.

По одной из версий, члены банды ещё во время ремонтных работ спрятали в школе оружие: учитель труда и завхоз чинили прогнивший пол, и как раз в эти полости боевики положили часть арсенала. Подтверждения этим сведениям нет: очевидцы последующих событий говорили, что не видели никакого оружия в пробитых настилах.

Формирование отряда, который готовился к атаке, боевики завершили в августе. Планированием занимались лидеры бандподполья Аслан Масхадов, Шамиль Басаев и Абу Дзейт. Они набрали рецидивистов, преступников, участников боевых действий – в общей сложности 32 террориста, командиром которых был выбран Руслан Хучбаров. На тот момент Хучбаров уже находился в федеральном розыске – ему инкриминировали убийство.

Взрывная цепь

Лето 2004 года в Беслане выдалось особенно жарким. Августовский зной продолжился и в сентябре, из-за чего детей и родителей предупредили: линейка в школе начнётся раньше привычного – не в 10 утра, а в 9. На День знаний осетинские семьи шли в полном составе: несколько садиков города были закрыты на ремонт, поэтому родители были вынуждены брать с собой и младших детей, которых не с кем было оставить.

В это же время в город ворвались террористы. У них было две машины – «ГАЗ-66» и «Семёрка», которую они по дороге отобрали у участкового. В арсенале боевиков было 22 АК, 2 пулемёта РПК-74, 2 пулемёта ПКМ, танковый пулемёт Калашникова, 2 ручных противотанковых гранатомёта РПГ-7 и гранатомёты РПГ-18 «Муха». У захватчиков также были с собой медикаменты и провиант.

Боевики ворвались в школу со стороны переулка Школьного, чтобы перегородить мирным жителям возможные пути побега. Милиционеры, увидев происходящее, открыли огонь на поражение, но уничтожить удалось лишь одного боевика. К его телу никто не подойдёт ещё трое суток. Когда труп почернеет, в Беслане поползут слухи, что среди захватчиков были афроамериканцы.

Члены НВФ взяли в заложники 1 100 человек. Двух мужчин расстреляли при захвате. Детей, родителей и работников школы согнали в спортзал, который располагался по центру школы. У заложников отобрали телефоны и запретили им говорить на родном языке: общаться можно было только на русском.

Два десятка мужчин из числа мирных жителей сразу же получили приказ забаррикадировать входы и выходы. Террористы велели двигать к ним мебель, а окна – выбивать, чтобы минимизировать шансы правоохранительных органов на удачную газовую атаку. Коридоры строения заминировали самодельными взрывными устройствами, изготовленными из пластита и поражающих элементов. Бомбами начинили и сам спортзал – СВУ подвесили на баскетбольные кольца. Привести взрывчатку в действие террористы могли с помощью педалей, на которых посменно дежурили до окончания захвата. Позже, когда здание обследуют криминалисты, они отыщут на всех бомбах номера и заключат, что речь идёт о тщательно спланированной «взрывной цепи».

Первым из заложников застрелили Руслана Бетрозова. Он нарушил табу – пытался успокоить детей, оказавшихся в плену, на осетинском языке. Вторым погиб Вадим Боллоев. Он отказался встать на колени. Боевики нанесли ему увечья, от которых он скончался в муках.

Смерть по переписке

Спустя час после начала атаки у школы №1 был сформирован оперштаб. Во главе был президент РСО-Алания Александр Дзасохов, которого в последствии сменил начальник республиканского ФСБ. Жители соседних домов по распоряжению силовиков были эвакуированы, с дорог убрали машины, а саму школу оцепили. Николай Патрушев, который в те годы занимал пост директора ФСБ России, отдал распоряжение об экстренном направлении на объект подкрепления. Отряды Спецназа прибыли на место событий из Владикавказа, Ханкалы, Москвы и Ессентуков. В общей сложности у здания школы оказались 250 сотрудников органов. Снайперы заняли позиции на крышах ближайших домов. Также оперштаб отдал команду провести разведку местности, чтобы обнаружить вероятные скрытые подходы к школе.

В 11:05 террористы вышли на связь с силовиками. Не лично: боевики выпустили из школы Ларису Мамитову, которая доставила в оперштаб записку с требованиями. Записку Мамитова писала под диктовку. Из текста следовало, что захватчики настаивали на переговорах с президентом Ингушетии Муратом Зязиковым, а также «Дзасоховым» и «Рашайло». Фамилию последнего в списке политика заложница спутала с фамилией Рошаля, поэтому внизу сделала пометку – «дет. врач». По телефону, который был указан в записке, дозвониться не получилось.

К 16:30 количество убитых террористами мирных жителей достигло 21 человека. Тела погибших выбрасывали из окон заложники. Для 33-летнего Аслана Кудзаева это стало спасением: он подгадал момент и выпрыгнул из окна, таким образом сумев сбежать. Из следующей записки, переданной Мамитовой, следовало, что людей убили потому, что никто не позвонил по номеру телефона, указанному в послании. Номер был указан снова.

К вечеру в Беслан приехал Леонид Рошаль. Он попытался наладить переговоры с террористами, предложил им воду и еду. Боевики отказались говорить с врачом и не пустили его в здание.

Праздничные цветы стали едой

К утру 2 сентября, после экстренного заседания СовБеза ООН, террористам предложили деньги и коридор для безопасного отступления. Те ответили отказом. Президент Северной Осетии Александр Дзасохов попробовал действовать через собственные связи – он связался с Ахмедом Закаевым, одним из руководителей ЧРИ, у которого был выход на Масхадова. С просьбой связаться с организатором теракта и убедить его отпустить заложников Закаеву звонила и журналистка Анна Политковская. Таймураз Мамсуров, в те годы занимавший пост представителя президента России в Северной Осетии, также обращался к Закаеву с просьбой о содействии. Двое детей Мамсурова были в числе заложников.

Президент Ингушетии Руслан Аушев прибыл к захваченной школе в 16:00 второго дня теракта. Аушев стал единственным, кому удалось поговорить с террористами. Боевики отказались передать мирным жителям воду и продукты, привезённые главой республики, и сообщили, что заложники добровольно держат «сухую» голодовку. К слову, на тот момент люди вынуждены были есть лепестки цветов, которые принесли с собой на праздник, и высасывать жидкость из одежды, края которой опускали в помойные вёдра. Аушев смог договориться об освобождении 24 заложников. Вместе с людьми члены бандгруппы передали политику письмо, написанное, якобы, Шамилем Басаевым. В письме говорилось о возможности заключить перемирие – если ЧРИ получит независимость, боевики обещали мир для россиян и прекращение боевых действий. Этот принцип в письме назывался как «независимость в обмен на безопасность».

После переговоров с Аушевым в школе начался ад. Террористы, угрожая расстрелом, запретили заложникам пить воду. Посещения туалета отныне также стало табуированным. Людям сказали, что в воде – яд. И предложили им пить собственную мочу.

«Отстреливаться до последнего»

На третий день оперштаб договорился с террористами о том, чтобы забрать тела погибших в первый день – мирных жителей, которых после расстрела выбросили из окон. Захватчики поставили условие: за телами приедет открытый фургон, чтобы они могли видеть всё, что происходит. Условие было принято. Четверо спасателей отправились к стенам школы, но террористы открыли по ним огонь. Дмитрия Кормилина убили сразу же. Валерий Замараев скончался позже от потери крови. Воспользовавшись ситуацией, заложники, которые к тому моменту были уже в обморочном состоянии, бросились бежать – это был их шанс на спасение. Террористы пресекли попытку автоматными очередями. Погибли 29 человек.

Командир отряда Хучбаров дал приказ членам группы – отстреливаться до последнего и прекратить все переговоры, сообщает trud.ru. После того, как связь была оборвана в одностороннем порядке, сотрудникам спецслужб удалось перехватить разговор лидера группы захватчиков с Алиханом Мержоевым, боевиком ингушского джамаата «Халифат».

Мержоев в ходе разговора дал добро на план Хучбарова. В школе раздались взрывы.

Освобождение

По приказу оперштаба по террористам был открыт снайперский огонь. Две боевые группы ФСБ выдвинулись к зданию школы. Освободители заходили в трёх сторон – через столовую, библиотеку и тренажёрный зал. Женщин и детей боевики использовали, как живой жит. Одновременно началась эвакуация людей. Участвовали все – и спецслужбы, и милиция, и местные жители, у которых не было оружия. В штурмовой операции погибли 10 сотрудников спецслужб и 6 гражданских спасателей.

Носилок для раненых людей не хватало – их мастерили из лестниц. Машин скорой помощи тоже оказалось недостаточно, поэтому люди грузили пострадавших в свои машины и везли в местную больницу. Тех, кто получил особенно серьёзные ранения, доставляли во Владикавказ. Всего госпитализировано было больше 700 человек, большинство из которых были детьми.

Операция по уничтожению захватчиков 3 сентября продолжалась до полуночи. Отряд был уничтожен. В живых остался только один боевик – Нурпаша Кулаев. Он приговорён к пожизненному заключению и содержится в колонии особого режима «Полярная Сова».

Сравнивают с войной

Количество погибших не смогли подсчитать сразу – почти две сотни людей считались пропавшими без вести из-за того, что некоторых просто не могли опознать. По окончательным данным, жертвами трагедии стали 333 человека. 186 из них были детьми. 111 – родственниками и друзьями школьников. Теракт оставил круглыми сиротами 17 подростков. В статистические данные не вошли близкие заложников, которые не смогли перенести горе и напряжение – они умерли из-за тяжелой психологической травмы. Северная Осетия за 3 дня потеряла почти столько же людей, сколько за 4 года Великой Отечественной войны – тогда на фронте погибли 357 мужчин.

6 и 7 сентября 2004 года Россия скорбила по погибшим в школе №1 Беслана. Рядом со зданием, которое стало местом гибели детей и невинных жителей, строят храм.

Беслан. 10 лет спустя | Фотогалерея

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

Беслан. 10 лет спустя | Фотогалерея

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

© АиФ / Евгений Зиновьев

| Beslan school siege | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Second Chechen War, Terrorism in Russia and Islamic terrorism in Europe | |

From top left clockwise: the building of school No. 1 in 2008, the Orthodox cross in the gymnasium in memory of the victims, the «Tree of Sorrow» memorial cemetery, photos of the victims | |

| Location | Beslan, North Ossetia-Alania (Russia) |

| Coordinates | 43°11′03″N 44°32′27″E / 43.184104°N 44.540854°ECoordinates: 43°11′03″N 44°32′27″E / 43.184104°N 44.540854°E |

| Date | 1 September 2004 ~09:30 – 3 September 2004 ~17:00 (UTC+3) |

| Target | School Number One (SNO) |

| Attack type | Mass murder, hostage taking, terrorist attack, bombing, school shooting, shootout |

| Weapons | Firearms, explosives |

| Deaths | 333 (excluding 31 terrorists)[1] |

| Injured | Approximately 783[2] |

| Perpetrators | Riyad-us Saliheen |

| No. of participants | 32 |

| Motive | Independence for Chechnya and the withdrawal of Russian troops. |

The Beslan school siege (also referred to as the Beslan school hostage crisis or the Beslan massacre)[3][4][5] was a terrorist attack that started on 1 September 2004, lasted three days, involved the imprisonment of more than 1,100 people as hostages (including 777 children)[6] and ended with the deaths of 333 people, 186 of them children,[7] as well as 31 of the attackers.[1] It is considered to be the deadliest school shooting in history.[8]

The crisis began when a group of armed Chechen terrorists occupied School Number One (SNO) in the town of Beslan, North Ossetia (an autonomous republic in the North Caucasus region of Russia) on 1 September 2004. The hostage-takers were members of the Riyad-us Saliheen, sent by the Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev, who demanded Russian withdrawal from and recognition of the independence of Chechnya. On the third day of the standoff, Russian security forces stormed the building.

The event had security and political repercussions in Russia, leading to a series of federal government reforms consolidating power in the Kremlin and strengthening the powers of the President of Russia.[9] Criticisms of the Russian government’s management of the crisis have persisted, including allegations of disinformation and censorship in news media as well as questions about journalistic freedom,[10] negotiations with the terrorists, allocation of responsibility for the eventual outcome and the use of excessive force.[11][12][13][14][15]

Background[edit]

School No. 1 was one of seven schools in Beslan, a town of about 35,000 people in the republic of North Ossetia–Alania in Russia’s Caucasus. The school, located next to the district police station, housed approximately 60 teachers and more than 800 students.[16] Its gymnasium, where most of the hostages were held for 52 hours, was a recent addition, measuring 10 metres (33 ft) wide and 25 metres (82 ft) long.[17] There were reports that men disguised as repairmen had secreted weapons and explosives into the school during July 2004, something that the authorities later denied. However, several witnesses have since testified they were forced to help their captors remove the weapons from caches hidden in the school.[18][19] There were also claims that a «sniper’s nest» on the sports-hall roof had been set up in advance.[20]

Course of the crisis[edit]

Day one[edit]

The attack on the school took place on the 1st of September, the traditional start of the Russian school year, referred to as «First Bell» or Knowledge Day.[21][8]

On this day, children, accompanied by their parents and other relatives, attend ceremonies hosted by their school.[22] Because of the Knowledge Day festivities, the number of people in the schools was considerably higher than normal. Early in the morning, a group of several dozen heavily armed Islamic nationalist guerrillas left a forest encampment located in the vicinity of the village of Psedakh in the neighbouring republic of Ingushetia, east of North Ossetia and west of war-torn Chechnya. The terrorists wore green military camouflage and black balaclava masks, and in some cases were also wearing explosive belts and explosive underwear. On the way to Beslan, on a country road near the North Ossetian village of Khurikau, they captured an Ingush police officer, Major Sultan Gurazhev.[23] Gurazhev was left in a vehicle after the terrorists had reached Beslan and then ran toward the schoolyard[24] and went to the district police department to inform them of the situation, adding that his duty handgun and badge had been taken.[25]

At 09:11 local time, the terrorists arrived at Beslan in a GAZelle police van and a GAZ-66 military truck. Many witnesses and independent experts claim that there were two groups of attackers, and that the first group was already at the school when the second group arrived by truck.[26] At first, some at the school mistook the militants for Russian special forces practicing a security drill.[27] However, the attackers soon began shooting in the air and forcing everyone from the school grounds into the building. During the initial chaos, up to 50 people managed to flee and alert authorities about the situation.[28] A number of people also managed to hide in the boiler room.[17] After an exchange of gunfire against the police and an armed local civilian, in which reportedly one attacker was killed and two were wounded, the militants seized the school building.[29] Reports of the death toll from this shootout ranged from two to eight people, while more than a dozen people were injured.

The attackers took approximately 1,100 hostages.[11][30] The number of hostages was initially downplayed by the government to the 200–400 range, and then for an unknown reason announced to be exactly 354.[10] In 2005, the government’s total was put at 1,128.[12] The militants herded their captives into the school’s gym and confiscated all of their mobile phones under threat of death.[31] They ordered the hostages to speak in Russian and only when first spoken to. When a father named Ruslan Betrozov stood to calm people and repeat the rules in the local language of Ossetic, a gunman approached him, asked Betrozov if he was done, and then shot him in the head. Another father named Vadim Bolloyev, who refused to kneel, was also shot by a captor and then bled to death.[32] Their bodies were dragged from the sports hall, leaving a trail of blood later visible in the video made by the terrorists.

After gathering the hostages in the gym, the attackers singled out 15–20 adults who they thought were the strongest among the male teachers, school employees and fathers, and took them into a corridor next to the cafeteria on the second floor, where a deadly blast soon took place. An explosive belt on one of the female bombers detonated, killing another female bomber (it was also claimed the second woman died from a bullet wound[33]) and several of the selected hostages, as well as mortally injuring one male terrorist. According to the version presented by the surviving terrorist, the blast was actually triggered by the polkovnik (group leader); he had triggered the bomb by remote control to kill those who openly disagreed about the child hostages and to intimidate other possible dissenters.[34] The surviving hostages from this group were then ordered to lie down and were shot with an automatic rifle by another gunman; all but one of them were killed.[35][36][37][38][39] Karen Mdinaradze, the FC Alania team cameraman, survived the explosion as well as the shooting; when discovered to be still alive, he was allowed to return to the sports hall, where he lost consciousness.[32][40] The militants then forced other hostages to throw the bodies out of the building and to wash the blood off the floor.[41] One of these hostages, Aslan Kudzayev, escaped by jumping out of the window; the authorities briefly detained him as a suspected terrorist.[32]

Beginning of the siege[edit]

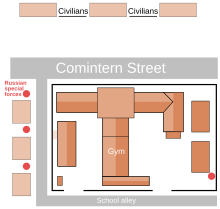

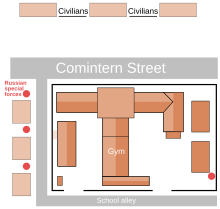

Overhead map of school showing initial positions of Russian forces

A security cordon was soon established around the school, consisting of the Russian police (militsiya), Internal Troops, Russian Army forces, Spetsnaz (including the elite Alpha and Vympel units of the (FSB) Russian Federal Security Service), and the OMON special units of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD). A line of three apartment buildings facing the school gym was evacuated and taken over by the special forces. The perimeter that they made was within 225 metres (738 ft) of the school, inside the range of the militants’ grenade launchers.[42] No firefighting equipment was in position and, despite the previous experiences of the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis, there were few ambulances ready.[17] The chaos was worsened by the presence of Ossetian volunteer militiamen (opolchentsy) and armed civilians among the crowds of relatives who had gathered at the scene,[43] altogether totaling perhaps as many as 5,000.[17]

The attackers mined the gym and the rest of the building with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and surrounded it with tripwires. In a further bid to deter rescue attempts, they threatened to kill 50 hostages for every one of their own members killed by the police, and to kill 20 hostages for every gunman injured.[17] They also threatened to blow up the school if government forces attacked. To avoid being overwhelmed by a gas attack as were their comrades in the 2002 Moscow hostage crisis, insurgents quickly smashed the school’s windows. The captors prevented hostages from eating and drinking (calling this a «hunger strike») until North Ossetia’s president Alexander Dzasokhov would arrive to negotiate with them.[41] However, the FSB set up its own crisis headquarters from which Dzasokhov was excluded, and threatened to arrest him if he tried to go to the school.[11][44]

The Russian government announced that it would not use force to rescue the hostages, and negotiations toward a peaceful resolution took place on the first and second days, at first led by Leonid Roshal, a pediatrician whom the hostage-takers had reportedly requested by name. Roshal had helped negotiate the release of children in the 2002 Moscow siege, but had also given advice to the Russian security services as they prepared to storm the theatre, for which he received the Hero of Russia award. However, a witness statement indicated that the Russian negotiators confused Roshal with Vladimir Rushailo, a Russian security official.[45] According to State Duma member Yuri Savelyev’s report, the official («civilian») headquarters sought a peaceful resolution while the secret («heavy») headquarters set up by the FSB was preparing the assault. Savelyev wrote that, in many ways, the «heavies» restricted the actions of the «civilians», in particular in their attempts to negotiate with the militants.[46]

At Russia’s request, a special meeting of the United Nations Security Council was convened on the evening of 1 September 2004, at which the council members demanded «the immediate and unconditional release of all hostages of the terrorist attack.»[47] U.S. president George W. Bush made a statement offering «support in any form» to Russia.[48]

Day two[edit]

On 2 September 2004, negotiations between Roshal and the militants proved unsuccessful, and they refused to allow food, water or medicine to be taken in for the hostages or for the dead bodies to be removed from the front of the school.[32] At noon, FSB First Deputy Director Colonel General Vladimir Pronichev showed Dzasokhov a decree signed by prime minister Mikhail Fradkov appointing the North Ossetian FSB chief, Major General Valery Andreyev, as head of the operational headquarters.[49] However, in April 2005 a Moscow News journalist received photocopies of the interview protocols of Dzasokhov and Andreyev by investigators, revealing that two headquarters had been formed in Beslan: a formal one, upon which was laid all responsibility, and a secret one («heavies»), which made the real decisions, and at which Andreyev had never been in charge.[50]

The Russian government downplayed the numbers, repeatedly stating there were only 354 hostages; this reportedly angered the hostage-takers, who further mistreated their captives.[51][52] Several officials also said there appeared to be only 15 to 20 militants in the school.[16] The crisis was met with a near-total silence from then-President of Russia Vladimir Putin and the rest of Russia’s political leaders.[53] Only on the second day did Putin make his first public comment on the siege during a meeting in Moscow with King Abdullah II of Jordan: «Our main task, of course, is to save the lives and health of those who became hostages. All actions by our forces involved in rescuing the hostages will be dedicated exclusively to this task.»[54] It was the only public statement by Putin about the crisis until one day after it ended.[53] In protest, several people at the scene raised signs reading: «Putin! Release our children! Meet their demands!» and «Putin! There are at least 800 hostages!» The locals also said that they would not allow any storming or «poisoning of their children» (an allusion to the Moscow hostage crisis chemical agent).[25]

Hundreds of hostages packed into the school gym with wired explosives attached to the basketball hoop (a frame from the Aushev tape)

In the afternoon, the gunmen allowed Ruslan Aushev, respected ex-president of Ingushetia and retired Soviet Army general, to enter the school building and agreed to personally release to him 11 nursing women and all 15 babies.[38][55] The women’s older children were left behind and one mother refused to leave, so Aushev carried out her youngest child instead.[35] The terrorists gave Aushev a videotape made in the school and a note with demands from their purported leader, Shamil Basayev, who was not present in Beslan. The existence of the note was kept secret by Russian authorities, while the tape was declared as being empty (which was later proved incorrect). It was falsely announced that the militants had made no demands.[11] In the note, Basayev demanded recognition of a «formal independence for Chechnya» in the framework of the Commonwealth of Independent States. He also said that although the Chechen separatists «had played no part» in the Russian apartment bombings of 1999, they would now publicly take responsibility for them if needed.[11] Some Russian officials and state-controlled media later criticised Aushev for entering the school, accusing him of colluding with the terrorists.[56]

The lack of food and water took a toll upon the young children, many of whom were forced to stand for long periods in the hot, tightly packed gym. Many children disrobed because of the sweltering heat in the gymnasium, which led to false rumors of sexual impropriety. Many children fainted, and parents feared that these children would die. Some hostages drank their own urine. Occasionally, the militants (many of whom took off their masks) took out some of the unconscious children and poured water on their heads before returning them to the sports hall. Later in the day, some adults also started to faint from fatigue and thirst. Because of the conditions in the gym, when the explosion and gun battle began on the third day, many of the surviving children were so fatigued that they were barely able to flee from the carnage.[31][57]

At about 15:30, two grenades were detonated by the militants against security forces outside the school approximately ten minutes apart,[58] setting a police car on fire and injuring one officer,[59] but Russian forces did not return fire. As the day and night wore on, the combination of stress and sleep deprivation—and possibly drug withdrawal[60]—made the hostage-takers increasingly hysterical and unpredictable. The crying of the children irritated them, and on several occasions crying children and their mothers were threatened that they would be shot if the crying did not cease.[27] Russian authorities claimed that the terrorists had «listened to German heavy metal group Rammstein on personal stereos during the siege to keep themselves edgy and fired up.» (Rammstein had previously come under fire following the Columbine High School massacre, and again in 2007 after the Jokela High School shooting).[61]

Overnight, a police officer was injured by shots fired from the school. Talks were broken off, resuming the next day.[54]

Day three[edit]

Early on the third day, Ruslan Aushev, Alexander Dzasokhov, Taymuraz Mansurov (North Ossetia’s parliament chairman) and First Deputy Chairman Izrail Totoonti together made contact with the president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, Aslan Maskhadov.[44] Totoonti said that both Maskhadov and his Western-based emissary Akhmed Zakayev declared that they were ready to fly to Beslan to negotiate with the militants, which was later confirmed by Zakayev.[62] Totoonti said that Maskhadov’s sole demand was his unhindered passage to the school; however, the assault began one hour after the agreement for his arrival was made.[63][64] He also mentioned that, for three days, journalists from Al Jazeera television offered to participate in the negotiations and enter the school, even as hostages, but were told «their services were not needed by anyone.»[65]

Russian presidential advisor, former police general and ethnic Chechen Aslambek Aslakhanov was also said to be close to a breakthrough in the secret negotiations. By the time that he left Moscow on the second day, Aslakhanov had accumulated the names of more than 700 well-known Russian figures who were volunteering to enter the school as hostages in exchange for the release of the children. Aslakhanov said that the hostage-takers agreed to allow him to enter the school the next day at 15:00. However, the storming had begun two hours before.[66]

The first explosions and the fire in the gymnasium[edit]

Rough plan of the situation

Masked hostage-taker standing on a dead man’s switch during the second day of the crisis (a frame from the Aushev tape)

Around 13:00 on 3 September, the militants allowed four Ministry of Emergency Situations medical workers in two ambulances to remove 20 bodies from the school grounds, as well as to bring the corpse of the killed terrorist to the school. However, at 13:03, when the paramedics approached the school, an explosion was heard from the gymnasium. The terrorists then opened fire on them, killing two.[41] The other two took cover behind their vehicle.

The second, «strange-sounding» explosion was heard 22 seconds later.[17] At 13:05, a fire started on the roof of the sports hall, and soon the burning rafters and roofing fell onto the hostages below, many of whom were injured but still alive.[46] Eventually, the entire roof collapsed, turning the room into an inferno. The flames reportedly killed some 160 people (more than half of all of the hostage fatalities).[20]

There are several conflicting opinions regarding the source and nature of the explosions:

- According to the December 2005 report by Stanislav Kesayev, deputy speaker of the North Ossetian parliament, some witnesses said that a federal-forces sniper had shot a militant whose foot was on a dead man’s switch detonator, triggering the first blast.[34][67] Captured terrorist Nur-Pashi Kulayev has testified to this, while a local policewoman and hostage named Fatima Dudiyeva said that she was shot in the hand «from outside» just before the explosion[12][67][68] and that there were three blasts: two small explosions at 13:03 followed by a larger one at 13:29.[69]

- According to State Duma member Yuri Savelyev, a weapons and explosives expert, the exchange of gunfire did not begin by explosions within the school building but by two shots fired from outside the school[70] and most of the homemade explosive devices installed by the terrorists did not explode at all. He said that the first shot was most likely fired by an RPO-A Shmel infantry rocket at the roof of nearby five-story House No. 37 on School Lane and aimed at the gymnasium’s attic, while the second was fired from an RPG-27 grenade launcher located at House No. 41 on the same street, destroying a fragment of the gym wall. Empty shells and launchers were found on the roofs of these houses, and alternative weapons mentioned in the report were RPG-26 or RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenades.[19][71][72] Savelyev, a dissenting member of the federal Torshin commission, headed by Alexander Torshin (see below), said that these explosions killed many of the hostages and that dozens more died in the resulting fire.[73] Yuri Ivanov, another parliamentary investigator, further contended that the grenades were fired on the direct orders of President Putin.[74] Several witnesses during the trial of Kulayev previously testified that the initial explosions were caused by projectiles fired from outside.[75]

- In the final report, Alexander Torshin, head of the Russian parliamentary commission that concluded its work in December 2006, said that the militants had started the battle by intentionally detonating bombs among the hostages, to the surprise of Russian negotiators and commanders. That statement went beyond previous government accounts that mentioned that the bombs had exploded in an unexplained accident.[76] Torshin’s 2006 report said that the taking of hostages was planned as a suicide attack from the beginning and that no storming of the building was prepared in advance.[75] According to testimonies by Nur-Pashi Kulayev and several former hostages and negotiators, the militants (including their leaders) blamed the government for the ensuing explosions.[12]

Storming by Russian forces[edit]

Part of the sports hall wall was demolished by the explosions, allowing some hostages to escape.[17] Local militia opened fire, and the military returned fire. A number of people were killed in the crossfire.[77] Russian officials say that militants shot hostages as they ran and that the military fired back.[67] The government asserts that once the shooting started, troops had no choice but to storm the building. However, some accounts by the town’s residents have contradicted that official version of events.[78]

Police lieutenant colonel Elbrus Nogayev, whose wife and daughter died in the school, said, «I heard a command saying, ‘Stop shooting! Stop shooting!’ while other troops’ radios said, ‘Attack!'»[42] As the fighting began, oil-company president and negotiator Mikhail Gutseriyev (an ethnic Ingush) phoned the hostage-takers and heard «You tricked us!» in response. Five hours later, Gutseriyev and his interlocutor reportedly had their last conversation, during which the man said, «The blame is yours and the Kremlin’s.»[66]

According to Torshin, the order to start the operation was given by the head of the North Ossetian FSB, Valery Andreyev.[79] However, statements by both Andreyev and Dzasokhov indicated that it was FSB deputy directors Vladimir Pronichev and Vladimir Anisimov who were actually in charge of the Beslan operation.[64] General Andreyev also told North Ossetia’s Supreme Court that the decision to use heavy weapons during the assault was made by the head of the FSB’s Special Operations Center, Colonel General Aleksandr Tikhonov.[80]

A chaotic battle broke out as the special forces fought to enter the school. The forces included the assault groups of the FSB and the associated troops of the Russian Army and the Russian Interior Ministry, supported by a number of T-72 tanks from Russia’s 58th Army (commandeered by Tikhonov from the military on 2 September), BTR-80 wheeled armoured personnel carriers and armed helicopters, including at least one Mi-24 attack helicopter.[81] Many local civilians also joined in the chaotic battle, having brought along their own weapons, and at least one of the armed volunteers is known to have been killed. Alleged crime figure Aslan Gagiyev claimed to be among them. At the same time, regular conscripted soldiers reportedly fled the scene as the fighting began. Civilian witnesses claimed that the local police also panicked, sometimes firing in the wrong direction.[82][83]

At least three, but as many as nine, powerful Shmel rockets were fired at the school from the special forces’ positions (three[12] or nine[84] empty disposable tubes were later found on the rooftops of nearby apartment blocks). The use of the Shmel rockets, classified in Russia as flamethrowers and in the West as thermobaric weapons, was initially denied, but later admitted by the government.[14][85] A report by an aide to the military prosecutor of the North Ossetian garrison stated that RPG-26 rocket-propelled grenades were used as well.[86] The terrorists also used grenade launchers, firing at the Russian positions in the apartment buildings.[17]