Людвиг ван Бетховен «Симфония №5»

Симфоническое творчество Бетховена ярко отражает человеческий путь преодоления, где судьба оказывается в руках человека. Пятая симфония Бетховена не является исключением. Эмоциональный надрыв и триумфальное торжество лирического героя над роковым началом — это настоящий призыв, посланный творцом сквозь времена, и дошедший до наших дней.

Историю создания «Симфонии №5» Бетховена, содержание произведения и множество интересных фактов читайте на нашей странице.

Краткая история «Симфонии №5»

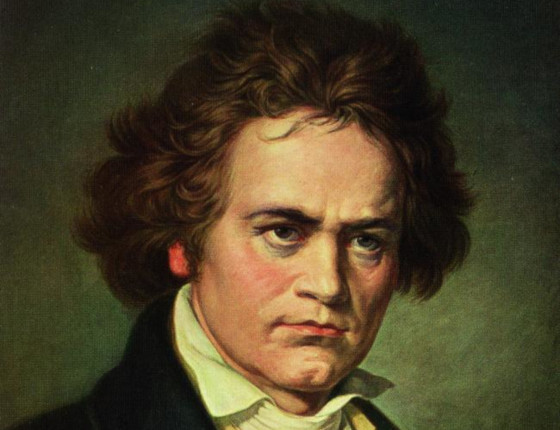

Времена, в которые создавалось произведение, были для композитора далеко не самыми благоприятными. Неприятности одна за другой настигали творца врасплох, вначале известие о глухоте, затем и военные действия в Австрии. Задумка столь грандиозного по масштабам произведения захватила разум Бетховена.

Но так как желание автора преодолевать все преграды на собственном пути могло быстро смениться самыми сумрачными и депрессивными мыслями, то сочинение постоянно откладывалось в долгий ящик. В зависимости от настроения Людвиг хватался то за одно, то за другое произведение, а пятая симфония и вовсе шла тяжело.

Бетховен не раз изменял финал, делая его то в позитивном, то в негативном ключе. Но в итоге, спустя три года, сочинение всё же увидело свет. Нельзя не отметить, что композитор одновременно писал две симфонии, и в одно и то же время их презентовал, поэтому впоследствии возникли некоторые неурядицы, касающиеся нумерации подобных крупных произведений.

На сегодняшний день произведение активно исполняется на ведущих сценах мира, но при этом первоначальная премьера в Театре Ан дер Вин прошла крайне неудачно. Можно выделить сразу несколько факторов, негативно повлиявших на восприятие слушателей:

- Концерт был затянут, так как Бетховен решил презентовать две симфонии сразу. Чтобы пятая симфония не была в списке последней, Людвигу пришлось вставить еще несколько номеров. В итоге публика устала от сложных, по-настоящему новаторских произведений.

- В концертном зале было очень холодно, так как помещение не отапливалось.

- Оркестр играл плохо, возможно из-за отсутствия благоприятных условий. Во время игры некоторые оркестранты допускали серьезные ошибки, из-за чего приходилось начинать произведение заново. Этот фактор дополнительно увеличивал время затянувшегося вечера музыки.

Интересно, что первоначальная неудача не смогла повлиять на популярность произведения. С каждым годом симфония становилась все более распространенной в кругах музыкального искусства. Среди многих последующих мастеров композиции сочинение было признано шедевром и эталоном классической симфонии.

Интересные факты

- Изначально, симфония №5 была обозначена №6, так как премьера двух этих популярнейших произведений была назначена в один и тот же день.

- Произведение посвящено двум прославленным в те времена меценатам, а именно князю Лобковицу и русскому послу в Австрии графу Разумовскому, которых своенравный Бетховен ценил за необыкновенные человеческие качества.

- Узнав о предстоящей глухоте, Бетховен хотел покончить собственную жизнь самоубийством. Единственное, что удерживало его от совершения настоящих действий – это творчество. В этот сложный период композитору пришла в голову мысль о создании данного, весьма героического по складу интонаций произведения.

- Изначально, произведение носило название «Большая симфония до минор», но потом сократилось до номерного порядка симфонии.

- Тональный план произведения от мрачного до минора в первой части до светлого и чистого до мажора в финале является концептуальным отражением идейных представлений Бетховена «от тьмы к свету» или «через препятствия к победе».

- Фрагменты симфонии активно цитируются в произведениях не менее известного композитора Альфреда Шнитке. К их числу относится «Первая симфония» и «Гоголь-сюита», сочиненная для оркестра.

- Людвиг ван Бетховен работал над произведением практически три года.

- Во время создания данного симфонического произведения композитор в собственном дневнике часто рассуждал о предназначении человека в этом мире. Он задавался вопросом о том, может ли человек изменить собственную жизнь, сделав ее неподвластной для роковых сил? Сам же гений и отвечал на поставленный вопрос: «Человек безгранично сильная и волевая натура, так отчего бы, она не смогла схватить судьбу за глотку?» Такие мысли можно было проследить на протяжении сочинения именно 5-й симфонии.

- Большинство драматургических концепций преодоления в творчестве музыкального деятеля находят собственные истоки в учениях великих философов, современников Людвига.

- Как известно, Вагнер был не силен в сочинении симфоний (после масштабной неудачи с сочинением Первой симфонии, где оркестровка была настолько неопытной и незрелой, что вызвала всеобщую насмешку, композитор переключился на оперное творчество, где и нашел собственное место, став реформатором), но симфоническое творчество Бетховена, а особенно пятое симфоническое произведение, он ценил превыше всех остальных.

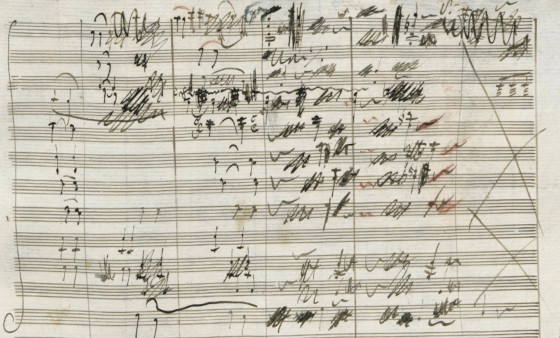

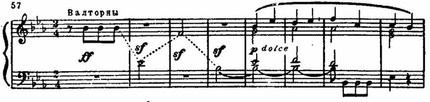

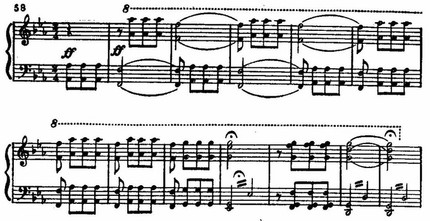

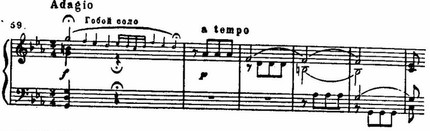

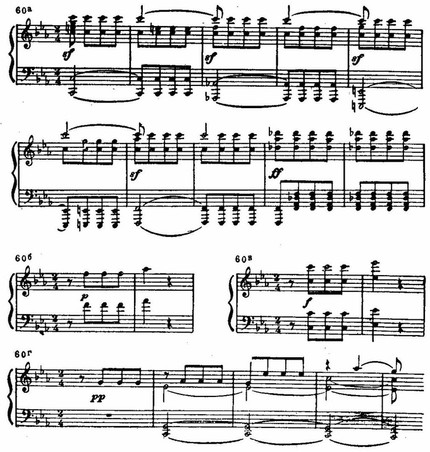

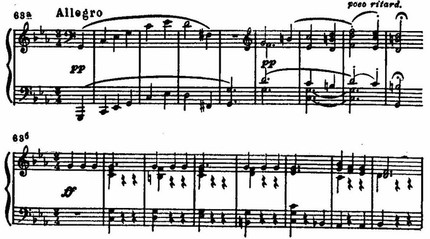

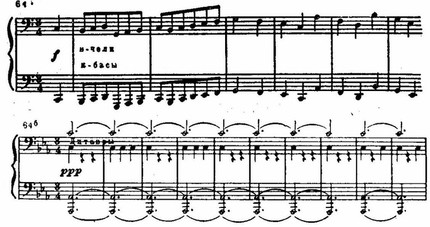

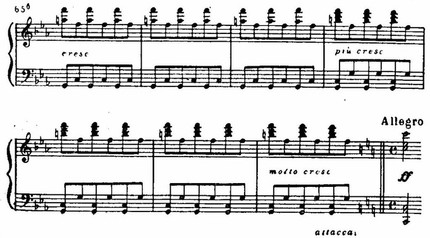

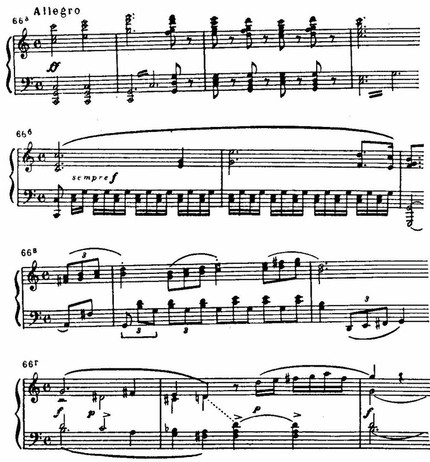

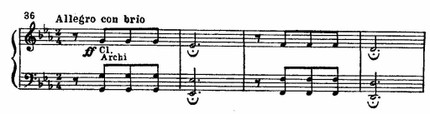

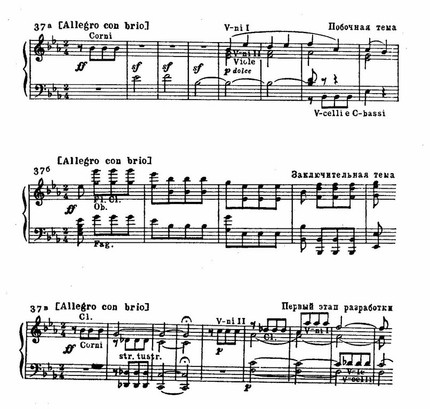

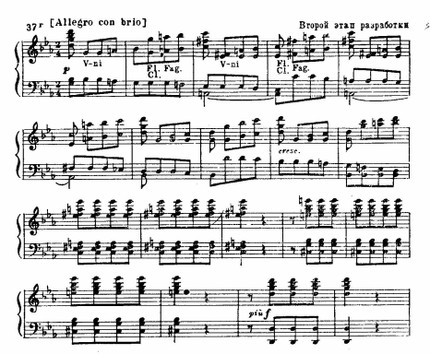

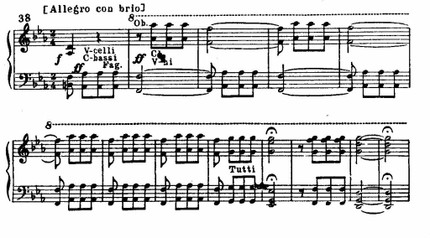

- Партитура «Симфонии №5» Бетховена.

Содержание «Симфонии №5» Бетховена

Бетховен не относится к композиторам, которые подробно описывают собственные произведения, давая им четкий и определенный программный замысел. Но симфония № 5 стала исключением из правила. В письме Шиндлеру он не только объяснил программный замысел, но и указал конкретные музыкальные темы, знаменующие рок и лирического героя, пытающегося бороться с судьбой.

Конфликт очевиден и его завязка происходит еще в первых тактах. Сам композитор, писал, что именно так «судьба стучится в двери». Он сравнивал ее с не прошеной гостьей, которая разрушает и врезается клином в привычный мир мечтаний и грез. Мотив судьбы пронизывает композицию с первых таков и помогает сделать цикл наиболее единым и слитным. Так как произведение написано в классическом стиле, то оно имеет структуру из четырех частей:

- I часть сочинена в форме сонатного allegro с медленным вступлением.

- II часть представляет собой двойные вариации.

- III часть – это драматическое скерцо, которое отражает жанрово-бытовую направленность.

- IV часть является финалом, написанным в форме сонатного allegro с кодой.

Жанр произведения представляет собой инструментальную драму. Из-за наличия программного замысла принято рассматривать содержание произведения с точки зрения драматургии. В таком случае, каждая часть симфонии представляет собой определенный этап и выполняет значимую драматургическую функцию:

- В первой части экспонируются прямое действие (лирический герой) и контрдействие (судьба) происходит завязка драмы и обострение конфликта. Преобладание и доминирование судьбы над героем.

- Вторая часть выполняет функцию разрядки нагнетенного противодействия, а также дает начало для формирования облика торжествующего финала.

- В третьей части конфликт накаляется и развивается до достижения острой стадии. Происходит перелом ситуации в пользу лирического героя. Характеризуется динамическим нарастанием.

- Финал явно формирует позитивный ключ и реализует концепцию «Через борьбу к победе».

Таким образом, композиция, представленная в данном произведении, является эталоном не только симфонического, но и драматургического мастерства.

Необычные современные обработки Симфонии №5

В настоящее время произведение является актуальным. Каждый образованный человек может узнать симфонию уже по первым тактам. Разумеется, многие современные музыканты не упускают возможности аранжировать или обработать данное симфоническое произведение. На данный момент можно выделить три наиболее часто встречающихся жанра, которые могут быть синтезированы с классической музыкой.

- Рок обработка «Пятой симфонии» еще больше подчеркивает конфликтную напряженность первой части. Использование электронных инструментов добавляет не только иного по краске звучания, но и делает мотив судьбы более острым, резким и неоднозначным. Тема лирического героя звучит боле сконцентрировано и отрывисто. Примечательно, что качественные обработки нисколько не портят произведение, а делают его более современным и актуальным для молодого поколения.

Рок обработка (слушать)

- Обработка Jazz отличается выдержкой джазовой стилистики. Но именно в данной обработке теряется драматичность, на смену ей приходит виртуозность исполнения. Накал произведения гасится, ритмичность добавляется за счет активной барабанной партии. Не маловажную роль в данной обработке играет группа медно-духовых и электрогитар. Трактовка произведения достаточно свободная, но имеет место быть в современном мире музыки.

Джаз обработка (слушать)

- Обработка в жанре «Сальса» представляет собой одну из самых необычных аранжировок Пятой симфонии Бетховена. Яркое сочетаниеавторских музыкальных тем и зажигательных ритмов и тембров латиноамериканской музыки, как ни странно, открывает новые грани и оттенки произведения. Идея соединить, казалось бы, не сочетаемые музыкальные стили принадлежит довольно известному в музыкальном мире норвежскому композитору и аранжировщику Сверре Индрис Йонеру.

Сальса (слушать)

Современные обработки классических произведений адаптируют сложный музыкальный материал для восприятия в обществе двадцать первого века. Такие аранжировки полезно слушать, с целью увеличить и расширить музыкальный кругозор. Некоторые варианты открывают принципиально новые грани в творчестве композитора, но и про классическую версию забывать не стоит.

Использование музыки Симфонии №5 в кинофильмах

Нельзя отрицать, что атмосфера триумфа и преодоления, переданная в музыке, а также ощущение напряжения в мотиве судьбы могут стать отличными инструментами для эмоционального окрашивания определенных моментов в кинематографе. Возможно, именно поэтому многие современные режиссеры используют произведение в собственных работах.

- Двенадцать друзей Оушена (2004);

- «Неуклюжая» (2014);

- «Специальное издание коллекционера» (2014);

- «Живые внутри» (2014);

- «Штурм белого дома» (2013);

- И всё же Лоранс (2012);

- «Другая сторона рая» (2009);

- «Будь что будет» (2009);

- Рождество с неудачниками (2004);

- Шашлык (2004);

- Питер Пэн (2003);

- Фантазия 2000 (1999);

- Знаменитость (1998);

- Как я провел свои каникулы (1992);

Пятая симфония Бетховена является не только вершиной симфонического творчества, но и ярким показателем индивидуальных особенностей стиля композитора. Нельзя понять истинного значения музыки, не познакомившись со столь грандиозной композицией. Музыка – это временное искусство, оно живет только во время исполнения. Симфония №5 доказывается, что даже временное искусство может быть вечным.

Понравилась страница? Поделитесь с друзьями:

Людвиг ван Бетховен «Симфония №5»

| Symphony in C minor | |

|---|---|

| No. 5 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Cover of the symphony, with the dedication to Prince J. F. M. Lobkowitz and Count Rasumovsky | |

| Key | C minor |

| Opus | 67 |

| Form | Symphony |

| Composed | 1804–1808 |

| Dedication |

|

| Duration | About 30–40 minutes |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 22 December 1808 |

| Location | Theater an der Wien, Vienna |

| Conductor | Ludwig van Beethoven |

The Symphony No. 5 in C minor of Ludwig van Beethoven, Op. 67, was written between 1804 and 1808. It is one of the best-known compositions in classical music and one of the most frequently played symphonies,[1] and it is widely considered one of the cornerstones of western music. First performed in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien in 1808, the work achieved its prodigious reputation soon afterward. E. T. A. Hoffmann described the symphony as «one of the most important works of the time». As is typical of symphonies during the Classical period, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony has four movements.

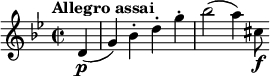

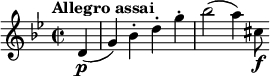

It begins with a distinctive four-note «short-short-short-long» motif:

The symphony, and the four-note opening motif in particular, are known worldwide, with the motif appearing frequently in popular culture, from disco versions to rock and roll covers, to uses in film and television.

Like Beethoven’s Eroica (heroic) and Pastorale (rural), Symphony No. 5 was given an explicit name besides the numbering, though not by Beethoven himself. It became popular under «Schicksals-Sinfonie» (Fate Symphony), and the famous five bar theme was called the «Schicksals-Motiv» (Fate Motif). This name is also used in translations.

History[edit]

Development[edit]

The Fifth Symphony had a long development process, as Beethoven worked out the musical ideas for the work. The first «sketches» (rough drafts of melodies and other musical ideas) date from 1804 following the completion of the Third Symphony.[2] Beethoven repeatedly interrupted his work on the Fifth to prepare other compositions, including the first version of Fidelio, the Appassionata piano sonata, the three Razumovsky string quartets, the Violin Concerto, the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, and the Mass in C. The final preparation of the Fifth Symphony, which took place in 1807–1808, was carried out in parallel with the Sixth Symphony, which premiered at the same concert.

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time; his personal life was troubled by increasing deafness.[3] In the world at large, the period was marked by the Napoleonic Wars, political turmoil in Austria, and the occupation of Vienna by Napoleon’s troops in 1805. The symphony was written at his lodgings at the Pasqualati House in Vienna. The final movement quotes from a revolutionary song by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle.

Premiere[edit]

The Fifth Symphony premiered on 22 December 1808 at a mammoth concert at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna consisting entirely of Beethoven premieres, and directed by Beethoven himself on the conductor’s podium.[4] The concert lasted for more than four hours. The two symphonies appeared on the programme in reverse order: the Sixth was played first, and the Fifth appeared in the second half.[5] The programme was as follows:

- The Sixth Symphony

- Aria: Ah! perfido, Op. 65

- The Gloria movement of the Mass in C major

- The Fourth Piano Concerto (played by Beethoven himself)

- (Intermission)

- The Fifth Symphony

- The Sanctus and Benedictus movements of the C major Mass

- A solo piano improvisation played by Beethoven

- The Choral Fantasy

Beethoven dedicated the Fifth Symphony to two of his patrons, Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky. The dedication appeared in the first printed edition of April 1809.

Reception and influence[edit]

There was little critical response to the premiere performance, which took place under adverse conditions. The orchestra did not play well—with only one rehearsal before the concert—and at one point, following a mistake by one of the performers in the Choral Fantasy, Beethoven had to stop the music and start again.[6] The auditorium was extremely cold and the audience was exhausted by the length of the programme. However, a year and a half later, publication of the score resulted in a rapturous unsigned review (actually by music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann) in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. He described the music with dramatic imagery:

Radiant beams shoot through this region’s deep night, and we become aware of gigantic shadows which, rocking back and forth, close in on us and destroy everything within us except the pain of endless longing—a longing in which every pleasure that rose up in jubilant tones sinks and succumbs, and only through this pain, which, while consuming but not destroying love, hope, and joy, tries to burst our breasts with full-voiced harmonies of all the passions, we live on and are captivated beholders of the spirits.[7]

Apart from the extravagant praise, Hoffmann devoted by far the largest part of his review to a detailed analysis of the symphony, in order to show his readers the devices Beethoven used to arouse particular affects in the listener. In an essay titled «Beethoven’s Instrumental Music», compiled from this 1810 review and another one from 1813 on the op. 70 string trios, published in three installments in December 1813, E.T.A. Hoffmann further praised the «indescribably profound, magnificent symphony in C minor»:

S

How this wonderful composition, in a climax that climbs on and on, leads the listener imperiously forward into the spirit world of the infinite!… No doubt the whole rushes like an ingenious rhapsody past many a man, but the soul of each thoughtful listener is assuredly stirred, deeply and intimately, by a feeling that is none other than that unutterable portentous longing, and until the final chord—indeed, even in the moments that follow it—he will be powerless to step out of that wondrous spirit realm where grief and joy embrace him in the form of sound….[8]

The symphony soon acquired its status as a central item in the orchestral repertoire. It was played in the inaugural concerts of the New York Philharmonic on 7 December 1842, and the [US] National Symphony Orchestra on 2 November 1931. It was first recorded by the Odeon Orchestra under Friedrich Kark in 1910. The First Movement (as performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra) was featured on the Voyager Golden Record, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space aboard the Voyager probes in 1977.[9] Groundbreaking in terms of both its technical and its emotional impact, the Fifth has had a large influence on composers and music critics,[10] and inspired work by such composers as Brahms, Tchaikovsky (his 4th Symphony in particular),[11] Bruckner, Mahler, and Berlioz.[12]

Since the Second World War, it has sometimes been referred to as the «Victory Symphony».[13] «V» is coincidentally also the Roman numeral character for the number five and the phrase «V for Victory» became a campaign of the Allies of World War II after Winston Churchill starting using it as a catchphrase in 1940. Beethoven’s Victory Symphony happened to be his Fifth (or vice versa) although this is coincidental. Some thirty years after this piece was written, the rhythm of the opening phrase – «dit-dit-dit-dah» – was used for the letter «V» in Morse code, though this is also coincidental. During the Second World War, the BBC prefaced its broadcasts to Special Operations Executives (SOE) across the world with those four notes, played on drums.[14][15][16] This was at the suggestion of intelligence agent Courtenay Edward Stevens.[17]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra:

Form[edit]

A typical performance usually lasts around 30–40 minutes. The work is in four movements:

- Allegro con brio (C minor)

- Andante con moto (A♭ major)

- Scherzo: Allegro (C minor)

- Allegro – Presto (C major)

I. Allegro con brio[edit]

The first movement opens with the four-note motif discussed above, one of the most famous motifs in Western music. There is considerable debate among conductors as to the manner of playing the four opening bars. Some conductors take it in strict allegro tempo; others take the liberty of a weighty treatment, playing the motif in a much slower and more stately tempo; yet others take the motif molto ritardando (a pronounced slowing through each four-note phrase), arguing that the fermata over the fourth note justifies this.[18] Some critics and musicians consider it crucial to convey the spirit of [pause]and-two-and one, as written, and consider the more common one-two-three-four to be misleading. Critic Michael Steinberg stated that with the «ta-ta-ta-Taaa», «Beethoven begins with eight notes». He points out that «they rhyme, four plus four, and each group of four consists of three quick notes plus one that is lower and much longer (in fact unmeasured).» As well, the «space between the two rhyming groups is minimal, about one-seventh of a second if we go by Beethoven’s metronome mark».[19]

In addition, «Beethoven clarifies the shape by lengthening the second of the long notes. This lengthening, which was an afterthought, is tantamount to writing a stronger punctuation mark. As the music progresses, we can hear in the melody of the second theme, for example (or later, in the pairs of antiphonal chords of woodwinds and strings (i.e. chords that alternate between woodwind and string instruments)), that the constantly invoked connection between the two four-note units is crucial to the movement.» Steinberg states that the «source of Beethoven’s unparalleled energy … is in his writing long sentences and broad paragraphs whose surfaces are articulated with exciting activity.» Indeed, «the double ‘ta-ta-ta-Taaa’ is an open-ended beginning, not a closed and self-sufficient unit (misunderstanding of this opening was nurtured by a nineteenth-century performance tradition in which the first five measures were read as a slow, portentous exordium, the main tempo being attacked only after the second hold).» He notes that the «opening [is] so dramatic» due to the «violence of the contrast between the urgency in the eighth notes and the ominous freezing of motion in the unmeasured long notes». He states that «the music starts with a wild outburst of energy but immediately crashes into a wall».[19]

Steinberg also asserts that «[s]econds later, Beethoven jolts us with another such sudden halt. The music draws up to a half-cadence on a G major chord, short and crisp in the whole orchestra, except for the first violins, who hang on to their high G for an unmeasured length of time. Forward motion resumes with a relentless pounding of eighth notes.»[20]

The first movement is in the traditional sonata form that Beethoven inherited from his Classical predecessors, such as Haydn and Mozart (in which the main ideas that are introduced in the first few pages undergo elaborate development through many keys, with a dramatic return to the opening section—the recapitulation—about three-quarters of the way through). It starts out with two dramatic fortissimo phrases, the famous motif, commanding the listener’s attention. Following the first four bars, Beethoven uses imitations and sequences to expand the theme, these pithy imitations tumbling over each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear to form a single, flowing melody. Shortly after, a very short fortissimo bridge, played by the horns, takes place before a second theme is introduced. This second theme is in E♭ major, the relative major, and it is more lyrical, written piano and featuring the four-note motif in the string accompaniment. The codetta is again based on the four-note motif. The development section follows, including the bridge. During the recapitulation, there is a brief solo passage for oboe in quasi-improvisatory style, and the movement ends with a massive coda.

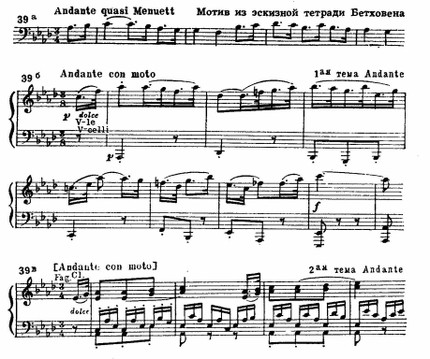

II. Andante con moto[edit]

The second movement, in A♭ major, the subdominant key of C minor’s relative key (E♭ major), is a lyrical work in double variation form, which means that two themes are presented and varied in alternation. Following the variations there is a long coda.

The movement opens with an announcement of its theme, a melody in unison by violas and cellos, with accompaniment by the double basses. A second theme soon follows, with a harmony provided by clarinets, bassoons, and violins, with a triplet arpeggio in the violas and bass. A variation of the first theme reasserts itself. This is followed up by a third theme, thirty-second notes in the violas and cellos with a counterphrase running in the flute, oboe, and bassoon. Following an interlude, the whole orchestra participates in a fortissimo, leading to a series of crescendos and a coda to close the movement.[21]

III. Scherzo: Allegro[edit]

The third movement is in ternary form, consisting of a scherzo and trio. While most symphonies before Beethoven’s time employed a minuet and trio as their third movement, Beethoven chose to use the newer scherzo and trio form.

The movement returns to the opening key of C minor and begins with the following theme, played by the cellos and double basses:

The opening theme is answered by a contrasting theme played by the winds, and this sequence is repeated. Then the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music proceeds from there. The trio section is in C major and is written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns for the final time, it is performed by the strings pizzicato and very quietly. «The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement [Andante con moto] in that they derive from extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio … The Scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous ‘motto’ (3 + 1) from the first movement, which gradually takes command of the whole movement.»[22] The third movement is also notable for its transition to the fourth movement, widely considered one of the greatest musical transitions of all time.[23]

IV. Allegro[edit]

The fourth movement begins without pause from the transition. The music resounds in C major, an unusual choice by the composer as a symphony that begins in C minor is expected to finish in that key.[24] In Beethoven’s words:

Many assert that every minor piece must end in the minor. Nego! …Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain.[25]

The triumphant and exhilarating finale is written in an unusual variant of sonata form: at the end of the development section, the music halts on a dominant cadence, played fortissimo, and the music continues after a pause with a quiet reprise of the «horn theme» of the scherzo movement. The recapitulation is then introduced by a crescendo coming out of the last bars of the interpolated scherzo section, just as the same music was introduced at the opening of the movement. The interruption of the finale with material from the third «dance» movement was pioneered by Haydn, who had done the same in his Symphony No. 46 in B, from 1772. It is unknown whether Beethoven was familiar with this work or not.[26]

The Fifth Symphony finale includes a very long coda, in which the main themes of the movement are played in temporally compressed form. Towards the end the tempo is increased to presto. The symphony ends with 29 bars of C major chords, played fortissimo. In The Classical Style, Charles Rosen suggests that this ending reflects Beethoven’s sense of proportions: the «unbelievably long» pure C major cadence is needed «to ground the extreme tension of [this] immense work.»[27]

Influences[edit]

The 19th century musicologist Gustav Nottebohm first pointed out that the third movement’s theme has the same sequence of intervals as the opening theme of the final movement of Mozart’s famous Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550. Here are the first eight notes of Mozart’s theme:

While such resemblances sometimes occur by accident, this is unlikely to be so in the present case. Nottebohm discovered the resemblance when he examined a sketchbook used by Beethoven in composing the Fifth Symphony: here, 29 bars of Mozart’s finale appear, copied out by Beethoven.[28][need quotation to verify]

Lore[edit]

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, scholarly articles, and program notes for live and recorded performances. This section summarizes some themes that commonly appear in this material.

Fate motif[edit]

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of Fate knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven’s secretary and factotum Anton Schindler, who wrote, many years after Beethoven’s death:

The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author’s presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: «Thus Fate knocks at the door!»[29]

Schindler’s testimony concerning any point of Beethoven’s life is disparaged by many experts (Schindler is believed to have forged entries in Beethoven’s so-called «conversation books», the books in which the deaf Beethoven got others to write their side of conversations with him).[30] Moreover, it is often commented that Schindler offered a highly romanticized view of the composer.

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from Antony Hopkins’s description of the symphony.[2] Carl Czerny (Beethoven’s pupil, who premiered the «Emperor» Concerto in Vienna) claimed that «the little pattern of notes had come to [Beethoven] from a yellow-hammer’s song, heard as he walked in the Prater-park in Vienna.» Hopkins further remarks that «given the choice between a yellow-hammer and Fate-at-the-door, the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though Czerny’s account is too unlikely to have been invented.»

In his Omnibus television lecture series in 1954, Leonard Bernstein likened the Fate Motif to the four note coda common to symphonies. These notes would terminate the symphony as a musical coda, but for Beethoven they become a motif repeating throughout the work for a very different and dramatic effect, he says.[31]

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. «The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest ‘Fate Knocking at the gate’ is apocryphal; Beethoven’s pupil, Ferdinand Ries, was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him.»[18] Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner remarks that «Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests»; this might be taken to impugn both tales.[32]

Beethoven’s choice of key[edit]

The key of the Fifth Symphony, C minor, is commonly regarded as a special key for Beethoven, specifically a «stormy, heroic tonality».[33] Beethoven wrote a number of works in C minor whose character is broadly similar to that of the Fifth Symphony. Pianist and writer Charles Rosen says,

Beethoven in C minor has come to symbolize his artistic character. In every case, it reveals Beethoven as Hero. C minor does not show Beethoven at his most subtle, but it does give him to us in his most extroverted form, where he seems to be most impatient of any compromise.[34]

Repetition of the opening motif throughout the symphony[edit]

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. «It is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony» (Doug Briscoe[35]); «a single motif that unifies the entire work» (Peter Gutmann[36]); «the key motif of the entire symphony»;[37] «the rhythm of the famous opening figure … recurs at crucial points in later movements» (Richard Bratby[38]). The New Grove encyclopedia cautiously endorses this view, reporting that «[t]he famous opening motif is to be heard in almost every bar of the first movement—and, allowing for modifications, in the other movements.»[39]

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly:

![relative c'' { set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn" key c minor time 3/4 set Score.currentBarNumber = #19 bar "" [ g4ff^"a 2" g g | g2. | ] g4 g g | g2. | g4 g g | <es g>2. | <g bes>4(<f as>) <es g>^^ | <bes f'>2. | }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/4/m4yao6q2552bav3f4sn930zntb6avmo/m4yao6q2.png)

In the second movement, an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c'' { time 3/8 key aes major set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible set Score.currentBarNumber = #75 bar "" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 partial 8 es16.(pp^"Violin I" f32) | repeat unfold 2 { ges4 es16.(f32) | } } new Staff relative c'' { key aes major override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 r8^"Violin II, Viola" | r32 [ a[pp a a] a16[ ] a] a r | r32 a[ a a] a16[ a] a r | } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/h/hh4e0qxxf3ldn95s76jx2mph7x0v5ik/hh4e0qxx.png)

In the finale, Doug Briscoe[35] suggests that the motif may be heard in the piccolo part, presumably meaning the following passage:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c'' { time 4/4 key c major set Score.currentBarNumber = #244 bar "" r8^"Piccolo" [ fis g g g2~ ] | repeat unfold 2 { g8 fis g g g2~ | } g8 fis g g g2 | } new Staff relative c { clef "bass" b2.^"Viola, Cello, Bass" g4(| b4 g d' c8. b16) | c2. g4(| c4 g e' d8. c16) | } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/e/meovyuwja1d5omfvjmgheutspcn7du1/meovyuwj.png)

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c' { time 2/2 key c major set Score.currentBarNumber = #362 bar "" tempo "Presto" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 c2.fp^"Violins" b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | c2. b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | repeat unfold 2 { <c e>2. <b d>4 | <a c>(<g b>) q-. q-. | } } new Staff relative c { time 2/2 key c major clef "bass" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 c4fp^"Bass instruments" r r2 | r4 [ g g g | c4fp ] r r2 | r4 g g g | repeat unfold 2 { c4fp r r2 | r4 g g g | } } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/h/5hptn69qj70v408t6s5h2za06ncaedh/5hptn69q.png)

On the other hand, some commentators are unimpressed with these resemblances and consider them to be accidental. Antony Hopkins,[2] discussing the theme in the scherzo, says «no musician with an ounce of feeling could confuse [the two rhythms]», explaining that the scherzo rhythm begins on a strong musical beat whereas the first-movement theme begins on a weak one. Donald Tovey[40] pours scorn on the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: «This profound discovery was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough.» Applied consistently, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other works by Beethoven are also «unified» with this symphony, as the motif appears in the «Appassionata» piano sonata, the Fourth Piano Concerto (![]() listen (help·info)), and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, «the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art.»

listen (help·info)), and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, «the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art.»

To Tovey’s objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven’s older Classical contemporaries such as Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, it is found in Haydn’s «Miracle» Symphony, No. 96 (![]() listen (help·info)) and in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 (

listen (help·info)) and in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 (![]() listen (help·info)). Such examples show that «short-short-short-long» rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven’s day.

listen (help·info)). Such examples show that «short-short-short-long» rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven’s day.

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins’s words) «remain eternally open to debate».[2]

Use of La Folia[edit]

La Folia Variation (measures 166–176)

Folia is a dance form with a distinctive rhythm and harmony, which was used by many composers from the Renaissance well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, often in the context of a theme and variations.[41] It was used by Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony in the harmony midway through the slow movement (bars 166–177).[42] Although some recent sources mention that the fragment of the Folia theme in Beethoven’s symphony was detected only in the 1990s, Reed J. Hoyt analyzed some Folia-aspects in the oeuvre of Beethoven already in 1982 in his «Letter to the Editor», in the journal College Music Symposium 21, where he draws attention to the existence of complex archetypal patterns and their relationship.[43]

New Instrumentation[edit]

The last movement of Beethoven’s Fifth is the first time the piccolo,[44] and contrabassoon were used in a symphony.[45] While this was Beethoven’s first use of the trombone in a symphony, in 1807 the Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert had specified trombones for his Symphony No. 3 in E♭ major.[46]

Textual questions[edit]

Third movement repeat[edit]

In the autograph score (that is, the original version from Beethoven’s hand), the third movement contains a repeat mark: when the scherzo and trio sections have both been played through, the performers are directed to return to the very beginning and play these two sections again. Then comes a third rendering of the scherzo, this time notated differently for pizzicato strings and transitioning directly to the finale (see description above). Most modern printed editions of the score do not render this repeat mark; and indeed most performances of the symphony render the movement as ABA’ (where A = scherzo, B = trio, and A’ = modified scherzo), in contrast to the ABABA’ of the autograph score. The repeat mark in the autograph is unlikely to be simply an error on the composer’s part. The ABABA’ scheme for scherzi appears elsewhere in Beethoven, in the Bagatelle for solo piano, Op. 33, No. 7 (1802), and in the Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies. However, it is possible that for the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven originally preferred ABABA’, but changed his mind in the course of publication in favor of ABA’.

Since Beethoven’s day, published editions of the symphony have always printed ABA’. However, in 1978 an edition specifying ABABA’ was prepared by Peter Gülke and published by Peters. In 1999, yet another edition, by Jonathan Del Mar, was published by Bärenreiter[47][48] which advocates a return to ABA’. In the accompanying book of commentary,[49] Del Mar defends in depth the view that ABA’ represents Beethoven’s final intention; in other words, that conventional wisdom was right all along.

In concert performances, ABA’ prevailed until the 2000s. However, since the appearance of the Gülke edition, conductors have felt more free to exercise their own choice. Performances with ABABA’ seem to be particularly favored by conductors who specialize in authentic performance or historically informed performance (that is, using instruments of the kind employed in Beethoven’s day and playing techniques of the period). These include Caroline Brown, Christopher Hogwood, John Eliot Gardiner, and Nikolaus Harnoncourt. ABABA’ performances on modern instruments have also been recorded by the New Philharmonia Orchestra under Pierre Boulez, the Tonhalle Orchester Zürich under David Zinman, and the Berlin Philharmonic under Claudio Abbado.

Reassigning bassoon notes to the horns[edit]

In the first movement, the passage that introduces the second subject of the exposition is assigned by Beethoven as a solo to the pair of horns.

![relative c'' { set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn" key c minor time 2/4 r8 bes[ff^"a 2" bes bes] | es,2sf | fsf | bes,sf | }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/5/35zj85hfekv8cov1f5htjuz2dpe058e/35zj85hf.png)

At this location, the theme is played in the key of E♭ major. When the same theme is repeated later on in the recapitulation section, it is given in the key of C major. Antony Hopkins writes:

This … presented a problem to Beethoven, for the horns [of his day], severely limited in the notes they could actually play before the invention of valves, were unable to play the phrase in the ‘new’ key of C major—at least not without stopping the bell with the hand and thus muffling the tone. Beethoven therefore had to give the theme to a pair of bassoons, who, high in their compass, were bound to seem a less than adequate substitute. In modern performances the heroic implications of the original thought are regarded as more worthy of preservation than the secondary matter of scoring; the phrase is invariably played by horns, to whose mechanical abilities it can now safely be trusted.[2]

In fact, even before Hopkins wrote this passage (1981), some conductors had experimented with preserving Beethoven’s original scoring for bassoons. This can be heard on many performances including those conducted by Caroline Brown mentioned in the preceding section as well as in 2003 recording by Simon Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic.[50] Although horns capable of playing the passage in C major were developed not long after the premiere of the Fifth Symphony (they were developed in 1814[51]), it is not known whether Beethoven would have wanted to substitute modern horns, or keep the bassoons, in the crucial passage.

Editions[edit]

- The edition by Jonathan Del Mar mentioned above was published as follows: Ludwig van Beethoven. Symphonies 1–9. Urtext. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1996–2000, ISMN M-006-50054-3.

- An inexpensive version of the score has been issued by Dover Publications. This is a 1989 reprint of an old edition (Braunschweig: Henry Litolff, no date).[52]

Cover versions and other uses in popular culture[edit]

The Fifth has been adapted many times to other genres, including the following examples:

- Franz Liszt arranged it for a piano solo in his Symphonies de Beethoven, S. 464.

- Electric Light Orchestra’s version of «Roll Over Beethoven» incorporates the motif and elements from the first movement into a classic rock and roll song by Chuck Berry.[53]

- Fantasia 2000 features a three-minute version of the first movement as its first segment.[54]

- An adaptation appears as the theme music for the TV show Judge Judy since its 9th season in 2004.[55]

- A disco arrangement appears as «A Fifth of Beethoven» by Walter Murphy on the soundtrack to the 1977 dance film Saturday Night Fever.

- The Brazilian telenovela Quanto Mais Vida, Melhor! presents a varied version of the composition in the opening theme, exploring different rhythms such as samba, classical music, pop and rock.[56]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Schauffler, Robert Haven (1933). Beethoven: The Man Who Freed Music. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, & Company. p. 211.

- ^ a b c d e Hopkins, Antony (1977). The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. Scolar Press. ISBN 1-85928-246-6.

- ^ «Beethoven’s deafness». lvbeethoven.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Kinderman, William (1995). Beethoven. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-520-08796-8.

- ^ Parsons, Anthony (1990). «Symphonic birth-pangs of the trombone». British Trombone Society. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Robbins Landon, H. C. (1992). Beethoven: His Life, Work, and World. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 149.

- ^ «Recension: Sinfonie … composée et dediée etc. par Louis van Beethoven. à Leipsic, chez Breitkopf et Härtel, Oeuvre 67. No. 5. des Sinfonies», Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 12, nos. 40 and 41 (4 and 11 July 1810): cols. 630–642 and 652–659. Citation in col. 633.

- ^ Published anonymously, «Beethovens Instrumental-Musik», Zeitung für die elegante Welt [de], nos. 245–247 (9, 10, and 11 December 1813): cols. 1953–1957, 1964–1967, and 1973–1975. Also published anonymously as part of Hoffmann’s collection titled Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier, 4 vols. Bamberg, 1814. English edition, as Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann, Fantasy Pieces in Callot’s Manner: Pages from the Diary of a Traveling Romantic, translated by Joseph M Hayse. Schenectady: Union College Press, 1996; ISBN 0-912756-28-4.

- ^ «Golden Record Music List». NASA. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Moss, Charles K. «Ludwig van Beethoven: A Musical Titan». Archived from the original on 22 December 2007..

- ^ Freed, Richard. «Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67». Archived from the original on 6 September 2005.

- ^ Rushton, Julian. The Music of Berlioz. p. 244.

- ^ «London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Josef Krips – The Victory Symphony (Symphony No. 5 in C major[sic], Op. 67)». Discogs. 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ «V-Campaign». A World of Wireless: Virtual Radiomuseum. Archived from the original on 12 March 2005. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Karpf, Jason (18 July 2013). «V for Victory and Viral». The Funky Adjunct. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ MacDonald, James (20 July 1941). «British Open ‘V’ Nerve War; Churchill Spurs Resistance». The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ «Mr C. E. Stevens». The Times. No. 59798. 2 September 1976.

- ^ a b Scherman, Thomas K. & Biancolli, Louis (1973). The Beethoven Companion. Garden City, New York: Double & Company. p. 570.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Michael (1995). The Symphony: A Listener’s Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512665-5. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael (1998). The Symphony. Oxford. p. 24.

- ^ Scherman & Biancolli (1973), p. 572.

- ^ Lockwood, Lewis (2003). Beethoven: The Music and the Life. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 223. ISBN 0-393-05081-5.

- ^ Kinderman, William (2009). Beethoven (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 150.

- ^ Lockwood, Lewis (2003). Beethoven: The Music and the Life. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 224. ISBN 0-393-05081-5.

- ^ Kerst, Friedrich; Krehbiel, Henry Edward, eds. (2008). Beethoven: The Man and the Artist, as Revealed in His Own Words. Translated by Henry Edward Krehbiel. Boston: IndyPublishing. p. 15.

- ^ James Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style, p. 267

- ^ Rosen, Charles (1997). The Classical Style (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 72.

- ^ Nottebohm, Gustav (1887). Zweite Beethoviana. Leipzig: C. F. Peters. p. 531.

- ^ Jolly, Constance (1966). Beethoven as I Knew Him. London: Faber and Faber. As translated from Schindler (1860). Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven.

- ^ Cooper, Barry (1991). The Beethoven Compendium. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-681-07558-9.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (14 December 2020). «Beethoven’s 250th Birthday: His Greatness Is in the Details». The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner. «Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 5, Op. 67». Classical Music Pages. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009.

- ^ Wyatt, Henry. «Mason Gross Presents—Program Notes: 14 June 2003». Mason Gross School of Arts. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006.

- ^ Rosen, Charles (2002). Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 134.

- ^ a b Briscoe, Doug. «Program Notes: Celebrating Harry: Orchestral Favorites Honoring the Late Harry Ellis Dickson». Boston Classic Orchestra. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- ^ Gutmann, Peter. «Ludwig Van Beethoven: Fifth Symphony». Classical Notes.

- ^ «Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. The Destiny Symphony». All About Beethoven.

- ^ Bratby, Richard. «Symphony No. 5». Archived from the original on 31 August 2005.

- ^ «Ludwig van Beethoven». Grove Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Tovey, Donald Francis (1935). Essays in Musical Analysis, Volume 1: Symphonies. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ «What is La Folia?». folias.nl. 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ «Bar 166». folias.nl. 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ «Which versions of La Folia have been written down, transcribed or recorded?». folias.nl. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Teng, Kuo-Jen. «The Piccolo in Beethoven’s Orchestration». ProQuest. University of North Texas. ProQuest 1041239386. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Teng, Kuo-Jen (December 2011). The Role of the Piccolo in Beethoven’s Orchestration (PDF) (Doctor of Musical Arts thesis). University of North Texas. p. 5. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Kallai, Avishai. «Revert to Eggert». Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Del Mar, Jonathan, ed. (1999). Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

- ^ Del Mar, Jonathan (July–December 1999). «Jonathan Del Mar, New Urtext Edition: Beethoven Symphonies 1–9». British Academy Review. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ^ Del Mar, Jonathan, ed. (1999). Critical Commentary. Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

- ^ «CD review: Beethoven: Symphonies 1-9: Vienna Philharmonic/Rattle et al». The Guardian. 14 March 2003. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Ericson, John. «E. C. Lewy and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9».

- ^ Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, and 7 in Full Score (Ludwig van Beethoven). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26034-8.

- ^ Bentowski, Tom (28 March 1977). «Ludwig on the Charts». New York. p. 65.

- ^ Culhane, John; Disney, Roy E. (15 December 1999). Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope. New York: Disney Editions. ISBN 0-7868-6198-3.

- ^ Stamm, Michael (June 2012). «Beethoven in America». The Journal of American History. 99 (1): 321–322. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas129.

- ^ «Quanto Mais Vida, Melhor! tem trilha sonora de impressionar». observatoriodatv.uol.com.br. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Carse, Adam (July 1948). «The Sources of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.» Music & Letters, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 249–262.

- Guerrieri, Matthew (2012). The First Four Notes: Beethoven’s Fifth and the Human Imagination. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307593283.

- Knapp, Raymond (Summer 2000). «A Tale of Two Symphonies: Converging Narratives of Divine Reconciliation in Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth.» Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 291–343.

External links[edit]

- Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 – A Beginners’ Guide – Overview, analysis and the best recordings – The Classic Review

- General discussion and reviews of recordings

- Brief structural analysis

- Analysis of the Beethoven 5th Symphony, The Symphony of Destiny on the All About Ludwig van Beethoven Page

- Program notes for a performance by the National Symphony Orchestra, Washington, DC.

- Project Gutenberg has two MIDI-versions of Beethoven’s 5th symphony: Etext No. 117 and Etext No. 156

- Program notes for a performance & lecture by Jeffrey Kahane and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

- Sketch to the Scherzo from op. 67 Fifth Symphony from Eroica Skbk (1803) – Unheard Beethoven Website

- Original Finale in c minor to Fifth Symphony op. 67, Gardi 23 (1804) – Unheard Beethoven Website

- Symphony No. 5 played by British Symphony Orchestra, Felix Weingartner (rec. 1932)

- Symphony No. 5 played by NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini (rec. 1939)

- Symphony No. 5 played by Berliner Philharmoniker, Wilhelm Furtwängler (rec. 1947)

Scores[edit]

- Symphony No. 5: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Mutopia project has a piano reduction score of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony

- Public domain sheet music both typset and scanned on Cantorion.org

- Full Score of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony from Indiana University

| Symphony in C minor | |

|---|---|

| No. 5 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Cover of the symphony, with the dedication to Prince J. F. M. Lobkowitz and Count Rasumovsky | |

| Key | C minor |

| Opus | 67 |

| Form | Symphony |

| Composed | 1804–1808 |

| Dedication |

|

| Duration | About 30–40 minutes |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 22 December 1808 |

| Location | Theater an der Wien, Vienna |

| Conductor | Ludwig van Beethoven |

The Symphony No. 5 in C minor of Ludwig van Beethoven, Op. 67, was written between 1804 and 1808. It is one of the best-known compositions in classical music and one of the most frequently played symphonies,[1] and it is widely considered one of the cornerstones of western music. First performed in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien in 1808, the work achieved its prodigious reputation soon afterward. E. T. A. Hoffmann described the symphony as «one of the most important works of the time». As is typical of symphonies during the Classical period, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony has four movements.

It begins with a distinctive four-note «short-short-short-long» motif:

The symphony, and the four-note opening motif in particular, are known worldwide, with the motif appearing frequently in popular culture, from disco versions to rock and roll covers, to uses in film and television.

Like Beethoven’s Eroica (heroic) and Pastorale (rural), Symphony No. 5 was given an explicit name besides the numbering, though not by Beethoven himself. It became popular under «Schicksals-Sinfonie» (Fate Symphony), and the famous five bar theme was called the «Schicksals-Motiv» (Fate Motif). This name is also used in translations.

History[edit]

Development[edit]

The Fifth Symphony had a long development process, as Beethoven worked out the musical ideas for the work. The first «sketches» (rough drafts of melodies and other musical ideas) date from 1804 following the completion of the Third Symphony.[2] Beethoven repeatedly interrupted his work on the Fifth to prepare other compositions, including the first version of Fidelio, the Appassionata piano sonata, the three Razumovsky string quartets, the Violin Concerto, the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, and the Mass in C. The final preparation of the Fifth Symphony, which took place in 1807–1808, was carried out in parallel with the Sixth Symphony, which premiered at the same concert.

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time; his personal life was troubled by increasing deafness.[3] In the world at large, the period was marked by the Napoleonic Wars, political turmoil in Austria, and the occupation of Vienna by Napoleon’s troops in 1805. The symphony was written at his lodgings at the Pasqualati House in Vienna. The final movement quotes from a revolutionary song by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle.

Premiere[edit]

The Fifth Symphony premiered on 22 December 1808 at a mammoth concert at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna consisting entirely of Beethoven premieres, and directed by Beethoven himself on the conductor’s podium.[4] The concert lasted for more than four hours. The two symphonies appeared on the programme in reverse order: the Sixth was played first, and the Fifth appeared in the second half.[5] The programme was as follows:

- The Sixth Symphony

- Aria: Ah! perfido, Op. 65

- The Gloria movement of the Mass in C major

- The Fourth Piano Concerto (played by Beethoven himself)

- (Intermission)

- The Fifth Symphony

- The Sanctus and Benedictus movements of the C major Mass

- A solo piano improvisation played by Beethoven

- The Choral Fantasy

Beethoven dedicated the Fifth Symphony to two of his patrons, Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky. The dedication appeared in the first printed edition of April 1809.

Reception and influence[edit]

There was little critical response to the premiere performance, which took place under adverse conditions. The orchestra did not play well—with only one rehearsal before the concert—and at one point, following a mistake by one of the performers in the Choral Fantasy, Beethoven had to stop the music and start again.[6] The auditorium was extremely cold and the audience was exhausted by the length of the programme. However, a year and a half later, publication of the score resulted in a rapturous unsigned review (actually by music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann) in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. He described the music with dramatic imagery:

Radiant beams shoot through this region’s deep night, and we become aware of gigantic shadows which, rocking back and forth, close in on us and destroy everything within us except the pain of endless longing—a longing in which every pleasure that rose up in jubilant tones sinks and succumbs, and only through this pain, which, while consuming but not destroying love, hope, and joy, tries to burst our breasts with full-voiced harmonies of all the passions, we live on and are captivated beholders of the spirits.[7]

Apart from the extravagant praise, Hoffmann devoted by far the largest part of his review to a detailed analysis of the symphony, in order to show his readers the devices Beethoven used to arouse particular affects in the listener. In an essay titled «Beethoven’s Instrumental Music», compiled from this 1810 review and another one from 1813 on the op. 70 string trios, published in three installments in December 1813, E.T.A. Hoffmann further praised the «indescribably profound, magnificent symphony in C minor»:

S

How this wonderful composition, in a climax that climbs on and on, leads the listener imperiously forward into the spirit world of the infinite!… No doubt the whole rushes like an ingenious rhapsody past many a man, but the soul of each thoughtful listener is assuredly stirred, deeply and intimately, by a feeling that is none other than that unutterable portentous longing, and until the final chord—indeed, even in the moments that follow it—he will be powerless to step out of that wondrous spirit realm where grief and joy embrace him in the form of sound….[8]

The symphony soon acquired its status as a central item in the orchestral repertoire. It was played in the inaugural concerts of the New York Philharmonic on 7 December 1842, and the [US] National Symphony Orchestra on 2 November 1931. It was first recorded by the Odeon Orchestra under Friedrich Kark in 1910. The First Movement (as performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra) was featured on the Voyager Golden Record, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space aboard the Voyager probes in 1977.[9] Groundbreaking in terms of both its technical and its emotional impact, the Fifth has had a large influence on composers and music critics,[10] and inspired work by such composers as Brahms, Tchaikovsky (his 4th Symphony in particular),[11] Bruckner, Mahler, and Berlioz.[12]

Since the Second World War, it has sometimes been referred to as the «Victory Symphony».[13] «V» is coincidentally also the Roman numeral character for the number five and the phrase «V for Victory» became a campaign of the Allies of World War II after Winston Churchill starting using it as a catchphrase in 1940. Beethoven’s Victory Symphony happened to be his Fifth (or vice versa) although this is coincidental. Some thirty years after this piece was written, the rhythm of the opening phrase – «dit-dit-dit-dah» – was used for the letter «V» in Morse code, though this is also coincidental. During the Second World War, the BBC prefaced its broadcasts to Special Operations Executives (SOE) across the world with those four notes, played on drums.[14][15][16] This was at the suggestion of intelligence agent Courtenay Edward Stevens.[17]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra:

Form[edit]

A typical performance usually lasts around 30–40 minutes. The work is in four movements:

- Allegro con brio (C minor)

- Andante con moto (A♭ major)

- Scherzo: Allegro (C minor)

- Allegro – Presto (C major)

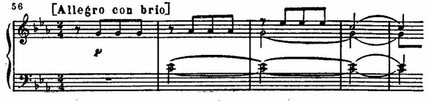

I. Allegro con brio[edit]

The first movement opens with the four-note motif discussed above, one of the most famous motifs in Western music. There is considerable debate among conductors as to the manner of playing the four opening bars. Some conductors take it in strict allegro tempo; others take the liberty of a weighty treatment, playing the motif in a much slower and more stately tempo; yet others take the motif molto ritardando (a pronounced slowing through each four-note phrase), arguing that the fermata over the fourth note justifies this.[18] Some critics and musicians consider it crucial to convey the spirit of [pause]and-two-and one, as written, and consider the more common one-two-three-four to be misleading. Critic Michael Steinberg stated that with the «ta-ta-ta-Taaa», «Beethoven begins with eight notes». He points out that «they rhyme, four plus four, and each group of four consists of three quick notes plus one that is lower and much longer (in fact unmeasured).» As well, the «space between the two rhyming groups is minimal, about one-seventh of a second if we go by Beethoven’s metronome mark».[19]

In addition, «Beethoven clarifies the shape by lengthening the second of the long notes. This lengthening, which was an afterthought, is tantamount to writing a stronger punctuation mark. As the music progresses, we can hear in the melody of the second theme, for example (or later, in the pairs of antiphonal chords of woodwinds and strings (i.e. chords that alternate between woodwind and string instruments)), that the constantly invoked connection between the two four-note units is crucial to the movement.» Steinberg states that the «source of Beethoven’s unparalleled energy … is in his writing long sentences and broad paragraphs whose surfaces are articulated with exciting activity.» Indeed, «the double ‘ta-ta-ta-Taaa’ is an open-ended beginning, not a closed and self-sufficient unit (misunderstanding of this opening was nurtured by a nineteenth-century performance tradition in which the first five measures were read as a slow, portentous exordium, the main tempo being attacked only after the second hold).» He notes that the «opening [is] so dramatic» due to the «violence of the contrast between the urgency in the eighth notes and the ominous freezing of motion in the unmeasured long notes». He states that «the music starts with a wild outburst of energy but immediately crashes into a wall».[19]

Steinberg also asserts that «[s]econds later, Beethoven jolts us with another such sudden halt. The music draws up to a half-cadence on a G major chord, short and crisp in the whole orchestra, except for the first violins, who hang on to their high G for an unmeasured length of time. Forward motion resumes with a relentless pounding of eighth notes.»[20]

The first movement is in the traditional sonata form that Beethoven inherited from his Classical predecessors, such as Haydn and Mozart (in which the main ideas that are introduced in the first few pages undergo elaborate development through many keys, with a dramatic return to the opening section—the recapitulation—about three-quarters of the way through). It starts out with two dramatic fortissimo phrases, the famous motif, commanding the listener’s attention. Following the first four bars, Beethoven uses imitations and sequences to expand the theme, these pithy imitations tumbling over each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear to form a single, flowing melody. Shortly after, a very short fortissimo bridge, played by the horns, takes place before a second theme is introduced. This second theme is in E♭ major, the relative major, and it is more lyrical, written piano and featuring the four-note motif in the string accompaniment. The codetta is again based on the four-note motif. The development section follows, including the bridge. During the recapitulation, there is a brief solo passage for oboe in quasi-improvisatory style, and the movement ends with a massive coda.

II. Andante con moto[edit]

The second movement, in A♭ major, the subdominant key of C minor’s relative key (E♭ major), is a lyrical work in double variation form, which means that two themes are presented and varied in alternation. Following the variations there is a long coda.

The movement opens with an announcement of its theme, a melody in unison by violas and cellos, with accompaniment by the double basses. A second theme soon follows, with a harmony provided by clarinets, bassoons, and violins, with a triplet arpeggio in the violas and bass. A variation of the first theme reasserts itself. This is followed up by a third theme, thirty-second notes in the violas and cellos with a counterphrase running in the flute, oboe, and bassoon. Following an interlude, the whole orchestra participates in a fortissimo, leading to a series of crescendos and a coda to close the movement.[21]

III. Scherzo: Allegro[edit]

The third movement is in ternary form, consisting of a scherzo and trio. While most symphonies before Beethoven’s time employed a minuet and trio as their third movement, Beethoven chose to use the newer scherzo and trio form.

The movement returns to the opening key of C minor and begins with the following theme, played by the cellos and double basses:

The opening theme is answered by a contrasting theme played by the winds, and this sequence is repeated. Then the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music proceeds from there. The trio section is in C major and is written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns for the final time, it is performed by the strings pizzicato and very quietly. «The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement [Andante con moto] in that they derive from extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio … The Scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous ‘motto’ (3 + 1) from the first movement, which gradually takes command of the whole movement.»[22] The third movement is also notable for its transition to the fourth movement, widely considered one of the greatest musical transitions of all time.[23]

IV. Allegro[edit]

The fourth movement begins without pause from the transition. The music resounds in C major, an unusual choice by the composer as a symphony that begins in C minor is expected to finish in that key.[24] In Beethoven’s words:

Many assert that every minor piece must end in the minor. Nego! …Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain.[25]

The triumphant and exhilarating finale is written in an unusual variant of sonata form: at the end of the development section, the music halts on a dominant cadence, played fortissimo, and the music continues after a pause with a quiet reprise of the «horn theme» of the scherzo movement. The recapitulation is then introduced by a crescendo coming out of the last bars of the interpolated scherzo section, just as the same music was introduced at the opening of the movement. The interruption of the finale with material from the third «dance» movement was pioneered by Haydn, who had done the same in his Symphony No. 46 in B, from 1772. It is unknown whether Beethoven was familiar with this work or not.[26]

The Fifth Symphony finale includes a very long coda, in which the main themes of the movement are played in temporally compressed form. Towards the end the tempo is increased to presto. The symphony ends with 29 bars of C major chords, played fortissimo. In The Classical Style, Charles Rosen suggests that this ending reflects Beethoven’s sense of proportions: the «unbelievably long» pure C major cadence is needed «to ground the extreme tension of [this] immense work.»[27]

Influences[edit]

The 19th century musicologist Gustav Nottebohm first pointed out that the third movement’s theme has the same sequence of intervals as the opening theme of the final movement of Mozart’s famous Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550. Here are the first eight notes of Mozart’s theme:

While such resemblances sometimes occur by accident, this is unlikely to be so in the present case. Nottebohm discovered the resemblance when he examined a sketchbook used by Beethoven in composing the Fifth Symphony: here, 29 bars of Mozart’s finale appear, copied out by Beethoven.[28][need quotation to verify]

Lore[edit]

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, scholarly articles, and program notes for live and recorded performances. This section summarizes some themes that commonly appear in this material.

Fate motif[edit]

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of Fate knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven’s secretary and factotum Anton Schindler, who wrote, many years after Beethoven’s death:

The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author’s presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: «Thus Fate knocks at the door!»[29]

Schindler’s testimony concerning any point of Beethoven’s life is disparaged by many experts (Schindler is believed to have forged entries in Beethoven’s so-called «conversation books», the books in which the deaf Beethoven got others to write their side of conversations with him).[30] Moreover, it is often commented that Schindler offered a highly romanticized view of the composer.

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from Antony Hopkins’s description of the symphony.[2] Carl Czerny (Beethoven’s pupil, who premiered the «Emperor» Concerto in Vienna) claimed that «the little pattern of notes had come to [Beethoven] from a yellow-hammer’s song, heard as he walked in the Prater-park in Vienna.» Hopkins further remarks that «given the choice between a yellow-hammer and Fate-at-the-door, the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though Czerny’s account is too unlikely to have been invented.»

In his Omnibus television lecture series in 1954, Leonard Bernstein likened the Fate Motif to the four note coda common to symphonies. These notes would terminate the symphony as a musical coda, but for Beethoven they become a motif repeating throughout the work for a very different and dramatic effect, he says.[31]

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. «The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest ‘Fate Knocking at the gate’ is apocryphal; Beethoven’s pupil, Ferdinand Ries, was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him.»[18] Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner remarks that «Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests»; this might be taken to impugn both tales.[32]

Beethoven’s choice of key[edit]

The key of the Fifth Symphony, C minor, is commonly regarded as a special key for Beethoven, specifically a «stormy, heroic tonality».[33] Beethoven wrote a number of works in C minor whose character is broadly similar to that of the Fifth Symphony. Pianist and writer Charles Rosen says,

Beethoven in C minor has come to symbolize his artistic character. In every case, it reveals Beethoven as Hero. C minor does not show Beethoven at his most subtle, but it does give him to us in his most extroverted form, where he seems to be most impatient of any compromise.[34]

Repetition of the opening motif throughout the symphony[edit]

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. «It is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony» (Doug Briscoe[35]); «a single motif that unifies the entire work» (Peter Gutmann[36]); «the key motif of the entire symphony»;[37] «the rhythm of the famous opening figure … recurs at crucial points in later movements» (Richard Bratby[38]). The New Grove encyclopedia cautiously endorses this view, reporting that «[t]he famous opening motif is to be heard in almost every bar of the first movement—and, allowing for modifications, in the other movements.»[39]

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly:

![relative c'' { set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn" key c minor time 3/4 set Score.currentBarNumber = #19 bar "" [ g4ff^"a 2" g g | g2. | ] g4 g g | g2. | g4 g g | <es g>2. | <g bes>4(<f as>) <es g>^^ | <bes f'>2. | }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/4/m4yao6q2552bav3f4sn930zntb6avmo/m4yao6q2.png)

In the second movement, an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c'' { time 3/8 key aes major set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible set Score.currentBarNumber = #75 bar "" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 partial 8 es16.(pp^"Violin I" f32) | repeat unfold 2 { ges4 es16.(f32) | } } new Staff relative c'' { key aes major override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 r8^"Violin II, Viola" | r32 [ a[pp a a] a16[ ] a] a r | r32 a[ a a] a16[ a] a r | } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/h/hh4e0qxxf3ldn95s76jx2mph7x0v5ik/hh4e0qxx.png)

In the finale, Doug Briscoe[35] suggests that the motif may be heard in the piccolo part, presumably meaning the following passage:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c'' { time 4/4 key c major set Score.currentBarNumber = #244 bar "" r8^"Piccolo" [ fis g g g2~ ] | repeat unfold 2 { g8 fis g g g2~ | } g8 fis g g g2 | } new Staff relative c { clef "bass" b2.^"Viola, Cello, Bass" g4(| b4 g d' c8. b16) | c2. g4(| c4 g e' d8. c16) | } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/e/meovyuwja1d5omfvjmgheutspcn7du1/meovyuwj.png)

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following:

![new StaffGroup << new Staff relative c' { time 2/2 key c major set Score.currentBarNumber = #362 bar "" tempo "Presto" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 c2.fp^"Violins" b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | c2. b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | repeat unfold 2 { <c e>2. <b d>4 | <a c>(<g b>) q-. q-. | } } new Staff relative c { time 2/2 key c major clef "bass" override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 c4fp^"Bass instruments" r r2 | r4 [ g g g | c4fp ] r r2 | r4 g g g | repeat unfold 2 { c4fp r r2 | r4 g g g | } } >>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/h/5hptn69qj70v408t6s5h2za06ncaedh/5hptn69q.png)

On the other hand, some commentators are unimpressed with these resemblances and consider them to be accidental. Antony Hopkins,[2] discussing the theme in the scherzo, says «no musician with an ounce of feeling could confuse [the two rhythms]», explaining that the scherzo rhythm begins on a strong musical beat whereas the first-movement theme begins on a weak one. Donald Tovey[40] pours scorn on the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: «This profound discovery was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough.» Applied consistently, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other works by Beethoven are also «unified» with this symphony, as the motif appears in the «Appassionata» piano sonata, the Fourth Piano Concerto (![]() listen (help·info)), and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, «the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art.»

listen (help·info)), and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, «the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art.»

To Tovey’s objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven’s older Classical contemporaries such as Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, it is found in Haydn’s «Miracle» Symphony, No. 96 (![]() listen (help·info)) and in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 (

listen (help·info)) and in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 (![]() listen (help·info)). Such examples show that «short-short-short-long» rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven’s day.

listen (help·info)). Such examples show that «short-short-short-long» rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven’s day.

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins’s words) «remain eternally open to debate».[2]

Use of La Folia[edit]

La Folia Variation (measures 166–176)

Folia is a dance form with a distinctive rhythm and harmony, which was used by many composers from the Renaissance well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, often in the context of a theme and variations.[41] It was used by Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony in the harmony midway through the slow movement (bars 166–177).[42] Although some recent sources mention that the fragment of the Folia theme in Beethoven’s symphony was detected only in the 1990s, Reed J. Hoyt analyzed some Folia-aspects in the oeuvre of Beethoven already in 1982 in his «Letter to the Editor», in the journal College Music Symposium 21, where he draws attention to the existence of complex archetypal patterns and their relationship.[43]

New Instrumentation[edit]

The last movement of Beethoven’s Fifth is the first time the piccolo,[44] and contrabassoon were used in a symphony.[45] While this was Beethoven’s first use of the trombone in a symphony, in 1807 the Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert had specified trombones for his Symphony No. 3 in E♭ major.[46]

Textual questions[edit]

Third movement repeat[edit]

In the autograph score (that is, the original version from Beethoven’s hand), the third movement contains a repeat mark: when the scherzo and trio sections have both been played through, the performers are directed to return to the very beginning and play these two sections again. Then comes a third rendering of the scherzo, this time notated differently for pizzicato strings and transitioning directly to the finale (see description above). Most modern printed editions of the score do not render this repeat mark; and indeed most performances of the symphony render the movement as ABA’ (where A = scherzo, B = trio, and A’ = modified scherzo), in contrast to the ABABA’ of the autograph score. The repeat mark in the autograph is unlikely to be simply an error on the composer’s part. The ABABA’ scheme for scherzi appears elsewhere in Beethoven, in the Bagatelle for solo piano, Op. 33, No. 7 (1802), and in the Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies. However, it is possible that for the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven originally preferred ABABA’, but changed his mind in the course of publication in favor of ABA’.