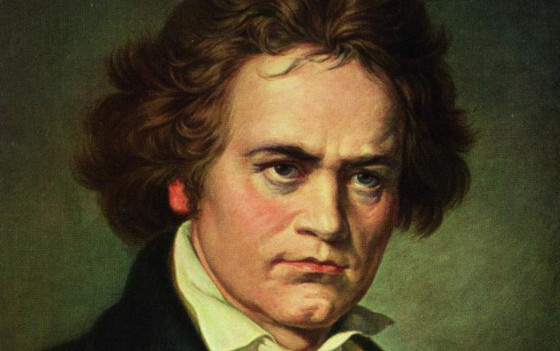

Людвиг ван Бетховен «Симфония №9»

Девятая симфония – это идейное завещание Бетховена, пламенное обращение ко всему человечеству. Замысел для создания столь грандиозного по масштабу произведения закладывался на протяжении всей жизни композитора. Музыка дает исчерпывающий ответ на вопросы мироздания, она обладает удивительным свойством существования вне исторического времени. Уникальность претворения финала, его своеобразное решение достигается включением кантаты «Ода к радости».

Девятая симфония – это идейное завещание Бетховена, пламенное обращение ко всему человечеству. Замысел для создания столь грандиозного по масштабу произведения закладывался на протяжении всей жизни композитора. Музыка дает исчерпывающий ответ на вопросы мироздания, она обладает удивительным свойством существования вне исторического времени. Уникальность претворения финала, его своеобразное решение достигается включением кантаты «Ода к радости».

Историю создания «Симфонии №9» Бетховена, содержание произведения и множество интересных фактов читайте на нашей странице.

История создания

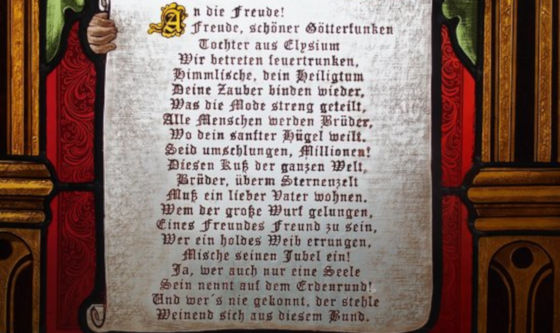

В 1785 году появилось произведение Шиллера «Ода к радости», призывающее людей к объединению и сплочению. Оно являлось отражением революционного времени, когда люди желали создать новое общество и сделать жизнь лучше. Сочинение несло не только общекультурную, но и социальную значимость. В последствие именно это произведение привлекло внимание одного из самых успешных композиторов современности — Людвига ван Бетховена.

С того самого времени, как он в первый раз прочел оду, творец задался задачей создания по-настоящему грандиозного произведения. Первые эскизы датируются 1809 годом. Спустя восемь лет композитор решил написать скерцо для симфонии. Работа над созданием шла медленно, Людвиг постоянно откладывал ее в сторону. Процесс сочинения ускорил поступивший заказ от Лондонского симфонического общества.

Тогда композитор был горячо любим в Англии, и даже планировал постепенно перебраться в страну туманного Альбиона. Но материальное положение не позволило ему осуществить собственные намерения. Он остался проживать в Германии. Еще в июле 1823 года Бетховен хотел создать два отдельных произведения — Девятую симфонию и произведение для хора «Ода к радости».

Но в процессе сочинения композитор понял, что необходимо объединить музыкальный материал. Синтез инструментальной и хоровой музыки в симфонической практике – это необычайная редкость для современности Бетховена. К счастью, риск был оправдан. Премьера, состоявшаяся 7 мая 1824 года в одном из фешенебельных театров Вены, прошла с оглушительным успехом. Зал рукоплескал, гул аплодисментов был нескончаемым. Жаль, что автор уже ничего не слышал. Несколько минут после того, как отзвучали последние аккорды, Бетховен не поворачивался к залу. По легенде, к нему подошла одна из хористок и показала, чтобы он повернулся к зрителям. Автор увидел, какое впечатление произвела симфония на людей. Благодарная публика кидала в воздух шляпы, некоторые плакали от счастья. Мечта Бетховена сбылась, музыка сумела объединить людей, сплотить их. Разве это не лучшая благодарность для творца?

Интересные факты

- Несмотря на то, что симфония еще раз подтвердила гениальность автора и была признана публикой, больших материальных средств она не принесла. Великий Бетховен еле сводил концы с концами. Иной раз он даже не выходил на улицу, так как его ботинки были давно изношены.

- Л.Н. Толстой не понимал творчества венского классика. В своем эссе писатель, рассуждая на тему «Что такое искусство?», назвал 9 симфонию дурным произведением, не имеющим отношения к искусству.

- Многие композиторы после Бетховена боялись браться за сочинение симфоний с номером 9. Так как существовало суеверие, что после написания симфонического произведения с номером 9, композитор вскоре должен умереть. После смерти Бетховена «проклятию» подверглись известные композиторы, а именно Франц Шуберт, Антонин Дворжак, Антон Брукнер. Считается, что данную связь между номером симфонии и окончанием пути проследил знаменитый композитор Густав Малер, который также скоропостижно покинул мир после девятой симфонии, которой дал подзаголовок «Песнь о Земле». Шёнберг считал, что те, кто пишут 9 симфонию, слишком близко подходят к черте потустороннего мира. Суеверие существует до сих пор, и многие композиторы боятся его.

- Дирижировал произведением известный в те времена дирижер и капельмейстер И. Умлацф. Бетховен стоял неподалеку и показывал темп. Оркестранты плохо разучили новое произведение, но даже небрежное отношение к новаторскому сочинению не повлияло на слушателей, они остались в восторге от премьеры.

- IV часть, а именно «Ода к радости» используется как «Гимн Евросоюза».

- Общее время сочинения от замысла до реализации составило примерно 15 лет.

- Сочинение посвящено королю Пруссии Фридриху-Вильгельму. Королевская особа на премьеру не явилась и самые дорогие места в концертном зале остались пустыми, поэтому исполнение симфонии не окупилось композитору, и гонорар оказался ничтожно мал.

- Компания Phillips при разработке компакт-диска специально увеличила его размер, чтобы на носитель помещалась аудиозапись симфонического цикла. Продолжительность симфонии – 74 минуты.

- По традиции в Японии в канун Нового года исполняется симфония Бетховена.

Содержание «Симфонии №9» Бетховена

Девятая симфония (d-moll) – это венец эпохи Просвещения. Классичность проявляется, прежде всего, в традиционно выверенной циклической форме, состоящей из четырех частей:

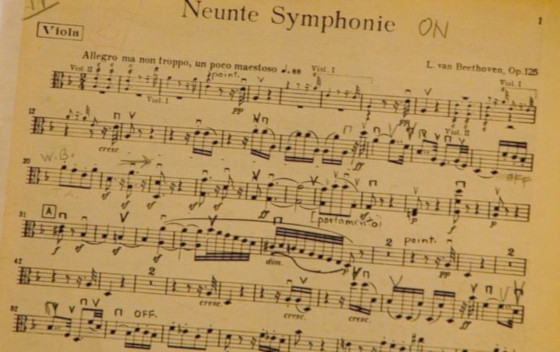

- Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (d-moll)

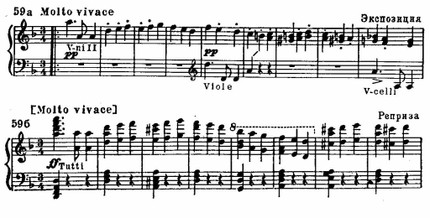

- Molto vivace (d-moll)

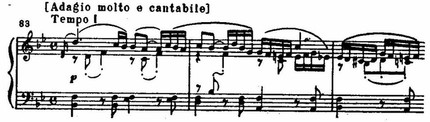

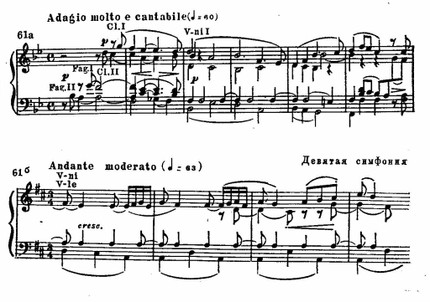

- Adagio molto e cantabile (B-dur)

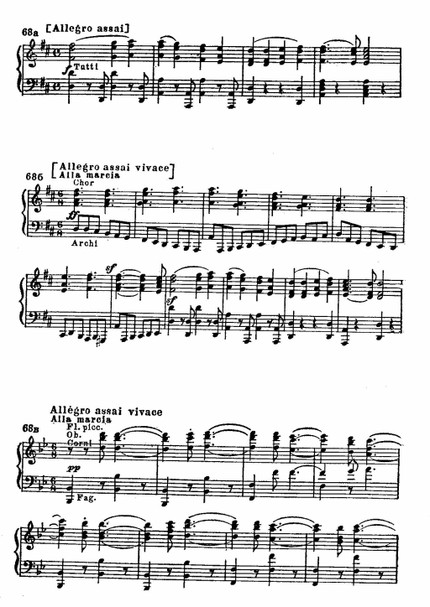

- Presto (d-moll — D-dur)

Выбранные тональности не случайны. Ре минор рассматривается как олицетворение скорби и печали. Постепенно напряжение снимается появлением Си-бемоль мажора, который знаменует и символизирует Веру, Надежду и Любовь, как опору всего в этом мире. Завершается грандиозная композиция ликованием в Ре мажоре, который принято соотносить с понятиями радости, счастья и жизни.

Новаторство Бетховена заключается в введении в инструментальную композицию вокальной музыки. Так классическая симфония расширяет собственные границы, постепенно, поэтапно трансформируясь в кантату. Многие музыкальные исследователи рассматривают финальное сочинение Бетховена, как «мессу», повествующую о Ветхом Завете. Произведение сочинялось параллельно с Торжественной мессой, и связано с ним неразрывными узами.

Первая часть рисует картину сотворения мира. Неясно звучат инструменты, будто бы оркестр только начинает настраиваться. Пусто и одновременно тембрально наполненно звучат квинтовые интонации. Постепенно из вступления рождается рельефная, пунктирная тема главной партии. Достигнув вершины, она скатывается в интонационную бездну. Смутное, грозовое настроение продолжает нарастать. Происходит внутренняя борьба, тучи сгущаются, фактура уплотняется. Словно светлый луч пронзает побочная партия. Мир лирики содержит в себе будущий материал для создания темы радости. Кульминацией первой части становится утвердительная и ясная заключительная партия. Она является вариантом главной партии, но существенно преобразованной, наполненной силой преодоления, решимости. Возвышаясь, заключительная партия скатывается к стихийной и необузданной разработке. Все меняется, трансформируется. Борьба и процесс становления сопровождаются яркими кульминациями и стремительными спадами. Настроения коды неоднозначны: траурный марш на фоне нисходящей по хроматизмам гаммы, символизирующей фигуру катабасис сменяется на главную тему, которая утвердительно завершает часть.

Вторая часть представляет уникальное для творчества Бетховена скерцо. В нем чувствуется бесконечная пульсация жизни. Музыка рисует жизнь, как счастливое бытие в раю. Основой для части является жанрово-бытовой тематизм, имеющий опору на песенные и танцевальные интонации. Необычна интерпретация традиционной трехчастной формы, как сонатной. Полифоничность наиболее ярко проявляется в виде фугато. Образный мир части подготавливает появление темы радости.

Третья часть – это удивительно глубокая, задумчивая музыка. Философия медленной части открывает слушателю мир души. Здесь царит светлая, архитектурная атмосфера, которая фундаментально держится на двух просветленных темах. Бесконечной кажется первая тема. Она развивается вариационно, и каждая вариация несет особую изысканность и уточненность. Вторая тема словно парит, кружится в вальсе. Танцевальность постепенно ослабевает и уже в коде резко врывается, нарушая гармонию, фанфарное звучание. Это напоминание о том, что совершенство еще не достигнуто. Идея объединения еще не материализовалась.

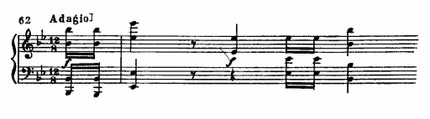

Оригинально претворение финала. Бетховен словно пытается кратко воспроизвести материал предыдущих частей. Фанфары ужаса, открывающие занавес четвертой части – как символ рока, призрак вступления первой части, он продолжается скерцозными интонациями второй и приходит к сладостному звучанию адажио. Наконец-то получает развитие подготавливаемый ранее материал для темы Радости. Легкое и прозрачное звучание деревянно-духовых инструментов утверждается и постепенно переходит в более сочный и низкий тембр виолончелей. Цепь вариацией разрастается с геометрической прогрессией, приводя ее к кульминации. Но голос оборвался вторжением фанфар ужаса. Тема радости излагается в партии бас-солиста. Картина торжества подхватывается звучным хором. Особенно ярко звучит тема «Обнимитесь миллионы!», которая в процессе будет виртуозно с точки зрения полифонии объединена с темой радости.

Неслучайно введение текста в симфонию, ведь в начале было слово. Как и искусство, слово помогает объединить людей. Кантата «Ода к Радости», включенная в симфонический цикл, это масштабный гимн человеческого духа.

Музыки Симфонии №9 в кинематографе

Девятая симфония совмещает полярные аффекты. Так эмоциональный накал может сменяться спокойствием и умиротворением, героичность уступает место лирическим моментам, светская по определению музыка имеет ярко выраженные черты религиозной музыки. Многогранность музыкального материала позволяет создать атмосферу, свойственную искусству кинематографа. Это определяет и объясняет популярность 9-й симфонии в современных фильмах.

- Симпсоны (2017)

- Бумажный дом (2017)

- История призрака (2017)

- Шерлок (2017)

- Юные преступники (2016)

- Поваренная книга алхимика (2016)

- Рождество (2015)

- Ловушка для приведения (2015)

- Экспериментатор (2015)

- Сверхъестественное (2012)

- Книга жизни (2014)

- Джон Уик (2014)

- Набережная Орсе (2013)

- Песня для Марион (2012)

В юношеские годы молодой Бетховен всерьёз говорил о том, что стремится служить своим искусством человечеству. В более взрослом возрасте, когда были изучены многие философские труды, композитор пришел к выводу, что искусство объединяет. Но ему не нужны были слова, все было сказано в музыке. Девятая симфония – это послание к человечеству. Эта музыка вечна. Искусство Бетховена заключалось в служении людям. Пройдя сквозь времена, его музыка стала носителем идеальной идеи о равенстве и братстве миллионов людей.

Понравилась страница? Поделитесь с друзьями:

Людвиг ван Бетховен «Симфония №9»

Symphony No. 9 (d-moll), Op. 125

Композитор

Год создания

1824

Дата премьеры

07.05.1824

Жанр

Страна

Германия

Послушать

Филадельфийский оркестр (дирижер Риккардо Мути)

I часть. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso

II часть. Molto vivace — Presto

III часть. Adagio molto e cantabile — Andante moderato

IV часть. Presto

Состав оркестра: 2 флейты, флейта-пикколо, 2 гобоя, 2 кларнета, 2 фагота, контрафагот, 4 валторны, 2 трубы, 3 тромбона, большой барабан, литавры, треугольник, тарелки, струнные; в финале — 4 солиста (сопрано, альт, тенор, бас) и хор.

История создания

Работа над грандиозной Девятой симфонией заняла у Бетховена два года, хотя замысел созревал в течение всей творческой жизни. Еще до переезда в Вену, в начале 1790-х годов, он мечтал положить на музыку, строфа за строфой, всю оду «К радости» Шиллера; при появлении в 1785 году она вызвала небывалый энтузиазм у молодежи пылким призывом к братству, единению человечества. Много лет складывалась и идея музыкального воплощения. Начиная с песни «Взаимная любовь» (1794) постепенно рождалась эта простая и величавая мелодия, которой было суждено в звучании монументального хора увенчать творчество Бетховена.

Набросок первой части симфонии сохранился в записной книжке 1809 года, эскиз скерцо — за восемь лет до создания симфонии. Небывалое решение — ввести в финал слово — было принято композитором после длительных колебаний и сомнений. Еще в июле 1823 года он предполагал завершить Девятую обычной инструментальной частью и, как вспоминали друзья, даже какое-то время после премьеры не оставил этого намерения.

Заказ на последнюю симфонию Бетховен получил от Лондонского симфонического общества. Известность его в Англии была к тому времени настолько велика, что композитор предполагал поехать в Лондон на гастроли и даже переселиться туда навсегда. Ибо жизнь первого композитора Вены складывалась трудно. В 1818 году он признавался: «Я дошел чуть ли не до полной нищеты и при этом должен делать вид, что не испытываю ни в чем недостатка». Бетховен вечно в долгах. Нередко он вынужден целыми днями оставаться дома, так как у него нет целой обуви. Издания произведений приносят ничтожный доход. Глубокое огорчение доставляет ему племянник Карл. После смерти брата композитор стал его опекуном и долго боролся с его недостойной матерью, стремясь вырвать мальчика из-под влияния этой «царицы ночи» (Бетховен сравнивал невестку с коварной героиней последней оперы Моцарта). Дядя мечтал, что Карл станет ему любящим сыном и будет тем близким человеком, который закроет ему глаза на смертном одре. Однако племянник вырос лживым, лицемерным бездельником, мотом, просаживавшим деньги в игорных притонах. Запутавшись в карточных долгах, он пытался застрелиться, но выжил. Бетховен же был так потрясен, что, по словам одного из друзей, сразу превратился в разбитого, бессильного 70-летнего старика. Но, как писал Роллан, «страдалец, нищий, немощный, одинокий, живое воплощение горя, он, которому мир отказал в радостях, сам творит Радость, дабы подарить ее миру. Он кует ее из своего страдания, как сказал сам этими гордыми словами, которые передают суть его жизни и являются девизом каждой героической души: через страдание — радость».

Премьера Девятой симфонии, посвященной королю Пруссии Фридриху-Вильгельму III, герою национально-освободительной борьбы немецких княжеств против Наполеона, состоялась 7 мая 1824 года в венском театре «У Каринтийских ворот» в очередном авторском концерте Бетховена, так называемой «академии». Композитор, полностью потерявший слух, только показывал, стоя у рампы, темп в начале каждой части, а дирижировал венский капельмейстер И. Умлауф. Хотя из-за ничтожно малого количества репетиций сложнейшее произведение было разучено плохо, Девятая симфония сразу же произвела потрясающее впечатление. Бетховена приветствовали овациями более продолжительными, чем по правилам придворного этикета встречали императорскую семью, и только вмешательство полиции прекратило рукоплескания. Слушатели бросали в воздух шляпы и платки, чтобы не слышавший аплодисментов композитор мог видеть восторг публики; многие плакали. От пережитого волнения Бетховен лишился чувств.

Девятая симфония подводит итог исканиям Бетховена в симфоническом жанре и прежде всего в воплощении героической идеи, образов борьбы и победы, — исканиям, начатым за двадцать лет до того в Героической симфонии. В Девятой он находит наиболее монументальное, эпическое и в то же время новаторское решение, расширяет философские возможности музыки и открывает новые пути для симфонистов XIX века. Введение же слова облегчает восприятие сложнейшего замысла композитора для самых широких кругов слушателей.

Музыка

Первая часть — сонатное аллегро грандиозного масштаба. Героическая тема главной партии утверждается постепенно, рождаясь из таинственного, отдаленного, неоформленного гула, словно из бездны хаоса. Подобно отблескам молний, мелькают краткие, приглушенные мотивы струнных, которые постепенно крепнут, собираясь в энергичную суровую тему по тонам нисходящего минорного трезвучия, с пунктирным ритмом, провозглашаемую, наконец, всем оркестром в унисон (медная группа усилена — впервые в симфонический оркестр включены 4 валторны). Но тема не удерживается на вершине, скатывается в бездну, и вновь начинается ее собирание. Громовые раскаты канонических имитаций tutti, резкие сфорцандо, отрывистые аккорды рисуют разворачивающуюся упорную борьбу. И тут же мелькает луч надежды: в нежном двухголосном пении деревянных духовых впервые появляется мотив будущей темы радости. В лирической, более светлой побочной партии слышатся вздохи, но мажорный лад смягчает скорбь, не дает воцариться унынию. Медленное, трудное нарастание приводит к первой победе — героической заключительной партии. Это вариант главной, теперь энергично устремленной вверх, утверждаемой в мажорных перекличках всего оркестра. Но опять все срывается в бездну: разработка начинается подобно экспозиции. Словно бушующие волны безбрежного океана вздымается и опадает музыкальная стихия, живописуя грандиозные картины суровой битвы с тяжкими поражениями, страшными жертвами. Иногда кажется, что светлые силы изнемогают и воцаряется могильная тьма. Начало репризы возникает непосредственно на гребне разработки: впервые мотив главной партии звучит в мажоре. Это предвестник далекой еще победы. Правда, торжество недолго — вновь воцаряется основная минорная тональность. И тем не менее, хотя до окончательной победы еще далеко, надежда крепнет, светлые темы занимают большее место, чем в экспозиции. Однако развернутая кода — вторая разработка — при водит к трагедии. На фоне мерно повторяющейся зловещей нисходящей хроматической гаммы звучит траурный марш… И все же дух не сломлен — часть завершается мощным звучанием героической главной темы.

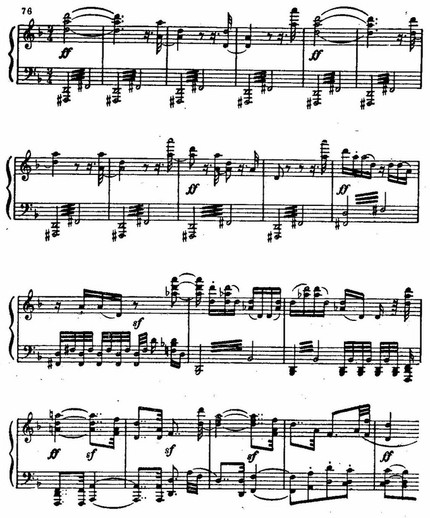

Вторая часть — уникальное скерцо, полное столь же упорной борьбы. Для ее воплощения композитору понадобилось более сложное, чем обычно, построение, и впервые крайние разделы традиционной трехчастной формы da capo оказываются написанными в сонатной форме — с экспозицией, разработкой, репризой и кодой. К тому же тема в головокружительно быстром темпе изложена полифонически, в виде фугато. Единый энергичный острый ритм пронизывает все скерцо, несущееся подобно неодолимому потоку. На гребне его всплывает краткая побочная тема — вызывающе дерзкая, в плясовых оборотах которой можно расслышать будущую тему радости. Искусная разработка — с полифоническими приемами развития, сопоставлениями оркестровых групп, ритмическими перебивками, модуляциями в отдаленные тональности, внезапными паузами и угрожающими соло литавр — целиком построена на мотивах главной партии. Оригинально появление трио: резкая смена размера, темпа, лада — и ворчливое стаккато фаготов без паузы вводит совершенно неожиданную тему. Краткая, изобретательно варьируемая в многократных повторениях, она удивительно напоминает русскую плясовую, а в одной из вариаций даже слышны переборы гармоники (не случайно критик и композитор А. Н. Серов находил в ней сходство с Камаринской!). Однако интонационно тема трио тесно связана с образным миром всей симфонии — это еще один, наиболее развернутый эскиз темы радости. Точное повторение первого раздела скерцо (da capo) приводит к коде, в которой тема трио всплывает кратким напоминанием.

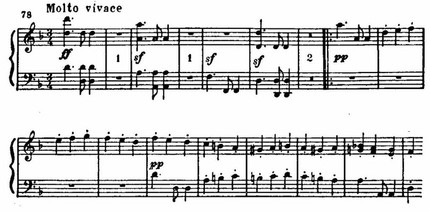

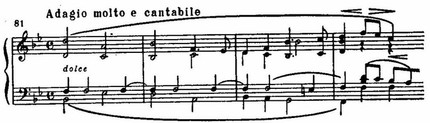

Впервые в симфонии Бетховен ставит на третье место медленную часть — проникновенное, философски углубленное адажио. В нем чередуются две темы — обе просветленно-мажорные, неторопливые. Но первая — напевная, в аккордах струнных со своеобразным эхом духовых, — кажется бесконечной и, повторяясь трижды, развивается в форме вариаций. Вторая же, с мечтательной, экспрессивной кружащейся мелодией напоминает лирический медленный вальс и возвращается еще раз, изменяя лишь тональность и оркестровый наряд. В коду (последнюю вариацию первой темы) дважды резким контрастом врываются героические призывные фанфары, словно напоминая, что борьба не завершена.

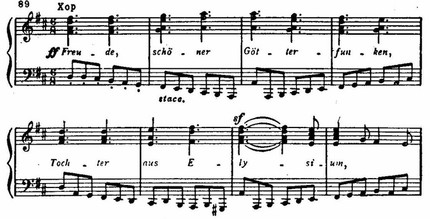

О том же повествует и начало финала, открывающегося, по определению Вагнера, трагической «фанфарой ужаса». Ей отвечает речитатив виолончелей и контрабасов, словно вызывающих, а затем отвергающих темы предшествующих частей. Вслед за повторением «фанфары ужаса» возникает призрачный фон начала симфонии, затем — мотив скерцо и, наконец, три такта певучего адажио. Последним появляется новый мотив — его поют деревянные духовые, и отвечающий ему речитатив впервые звучит утвердительно, в мажоре, непосредственно переходя в тему радости. Это соло виолончелей и контрабасов — удивительная находка композитора. Песенная тема, близкая народной, но преображенная гением Бетховена в обобщенно-гимническую, строгую и сдержанную, развивается в цепи вариаций. Разрастаясь до грандиозного ликующего звучания, тема радости на кульминации внезапно обрывается новым вторжением «фанфары ужаса». И только после этого последнего напоминания о трагической борьбе вступает слово. Прежний инструментальный речитатив поручен теперь солисту-басу и переходит в вокальное же изложение темы радости на стихи Шиллера:

Радость, пламя неземное,

Райский дух, слетевший к нам,

Опьяненные тобою,

Входим мы в твой светлый храм!

Припев подхватывает хор, продолжается варьирование темы, в котором принимают участие солисты, хор и оркестр. Ничто не омрачает картины торжества, но Бетховен избегает однообразия, расцвечивая финал различными эпизодами. Один из них — военный марш в исполнении духового оркестра с ударными, солиста-тенора и мужского хора, — сменяется общей пляской. Другой — сосредоточенный величавый хорал «Обнимитесь, миллионы!» С уникальным мастерством композитор полифонически объединяет и разрабатывает обе темы — тему радости и тему хорала, еще сильнее подчеркивая величие празднества единения человечества.

А. Кенигсберг

Девятая симфония — одно из самых выдающихся творений в истории мировой музыкальной культуры. По величию идеи и глубине ее этического содержания, по широте замысла и мощной динамике музыкальных образов Девятая симфония превосходит все созданное самим же Бетховеном.

Хотя Девятая симфония — далеко не последнее творение Бетховена, именно она явилась сочинением, завершившим долголетние идейно-художественные искания композитора. В ней нашли высшее выражение бетховенские идеи демократизма и героической борьбы, в ней с несравненным совершенством воплощены новые принципы симфонического мышления.

В Девятой симфонии Бетховен ставит центральную для своего творчества жизненно важную проблему: человек и бытие, тираноборчество и сплоченность всех для победы справедливости и добра. Эта проблема ясно определилась в Третьей и Пятой симфониях, но в Девятой она приобретает характер всечеловеческий, вселенский. Отсюда — масштабы новаторства, грандиозность композиции, форм.

Идейная концепция симфонии привела к принципиальному изменению самого жанра симфонии и ее драматургии. В область чисто инструментальной музыки Бетховен вводит слово, звучание человеческих голосов,

Это открытие Бетховена не раз использовали композиторы XIX и XX веков.

Изменилась и сама организация симфонического цикла. Обычный принцип контраста (чередование быстрых и медленных частей) Бетховен подчиняет идее непрерывного образного развития. Вначале следуют одна за другой две быстрые части, где концентрируются самые драматические ситуации симфонии, а медленная часть, перемещенная на третье место, подготавливает — в лирико-философском плане — наступление финала. Таким образом, все движется к финалу — итогу сложнейших процессов жизненной борьбы, различные этапы и аспекты которой даны в предшествующих частях.

В Девятой симфонии Бетховен по-новому разрешает проблему тематического объединения цикла. Он углубляет интонационные связи между частями и, продолжая найденное в Третьей и Пятой симфониях, идет еще дальше по пути музыкальной конкретизации идейного замысла, или, иначе говоря, по пути к программности. В финале повторяются все темы предыдущих частей — своего рода музыкальное разъяснение замысла симфонии, за которым следует и словесное.

Первая часть. Allegro ma non troppo, un росо maestoso

Начальное Allegro Девятой симфонии очень точно и выразительно охарактеризовано А. Н. Серовым. Он пишет: «Это первое мрачное эпическое вступление пахнет кровавыми днями терроризма. Царство свободы и единения должно быть завоевано. Все ужасы войны — подкладка для этой первой части. Она ими чревата в каждой строке. Эти темные страницы служат художественным контрастом (repoussoir) для отдаленного еще Эллизия, но, кроме писательского приема, это, вместе — глубочайшее философское воплощение в звуках темных страниц истории человечества, страниц вечной борьбы, вечных сомнений, вечного уныния, вечной печали, среди которых — радость, счастье мелькают мимолетным, как молния, проблеском».

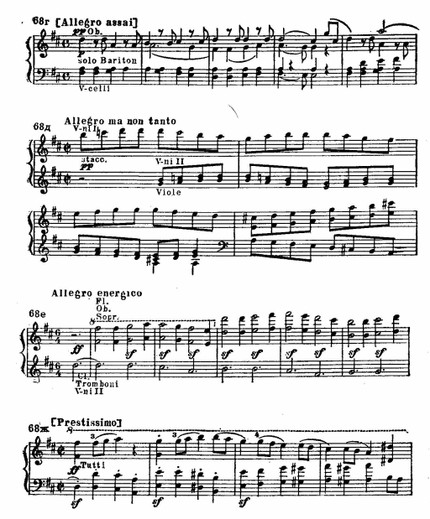

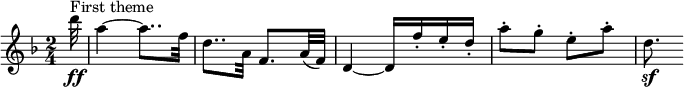

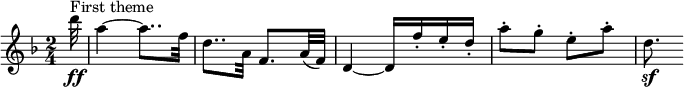

Действительно, трагически мрачные стороны жизни сильнее всего обрисованы в первой части симфонии, и ее главная тема, составляющая тематическую основу Allegro — средоточие всего враждебного человеку и человечеству. Что-то устрашающее слышится в непреклонности ритмических упоров оркестрового унисона, в маршеобразной чеканности каждого мотива:

В главной партии Бетховен показывает весь путь становления основной темы — от ее зарождения до окончательного трагического утверждения. Из смутных, неясных шорохов струнных на валторновой педали, из этого кажущегося хаоса и мерцания ниспадающих кварто-квинтовых мотивов (у первых скрипок) возникают едва уловимые контуры будущей темы:

Постепенно с каждой последующей фразой включаются новые инструменты (гобои, флейты), уплотняется фактура и, наконец, весь оркестровый массив обрушивается при появлении темы в ее окончательном виде. Такой прием последовательного «вызревания» темы, ее интонационной и психологической подготовки, использовали и развивали впоследствии Лист, Берлиоз и другие композиторы-романтики.

Замысел симфонии, характер тематизма, интенсивность развития привели к новому решению сонатной формы. Ее «вместимость» позволяла Бетховену в зрелых сочинениях свободно видоизменять все соотношения внутренних разделов. В Девятой симфонии разрастание сонатной формы, вызванное небывалой значительностью конфликта, превосходит даже Третью (Героическую) симфонию. В самых общих чертах эта тенденция обнаруживается в своеобразии строения главной партии, когда появлению главной темы предшествует длительная подготовка; в многотемности экспозиции: побочная партия состоит из целой группы тем, каждая тема, каждый мотив носит индивидуальный характер, обладает своим мелодико-ритмическим рисунком:

Многотемность экспозиции вызвана, по-видимому, стремлением противопоставить «надчеловечной» властности и монументализму главной темы мир лирических душевных переживаний и состояний.

Новизна сонатной формы сказывается и в слитности всех ее разделов. Экспозиция, не повторяясь, сразу переходит в разработку. В свою очередь разработка вторгается в репризу, ибо драматическая кульминация разработки (на вступлении к главной теме в D-dur) одновременно служит началом динамической репризы:

Реприза «подхватывает» разработку и, продолжая вести линию безостановочного драматического нагнетания, передает ее коде.

В образном движении Allegro кода — новая, но уже завершающая фаза. Драматизм конфликта, направляя сквозное развитие, концентрируется в узловых моментах сонатной формы. Кода — своего рода вторая разработка, где главная тема во взаимодействии с другим тематическим материалом подвергается множественным видоизменениям, особенно в заключительном разделе. Он начинается глухо, угрожающим звучанием хроматических ходов остинатного баса. На этом фоне вырисовывается, с каждым проведением все более четко, ритмический рисунок главной темы (деревянные и медные духовые):

Все пронзительней становится звук коротких трелей. Наконец, октавные унисоны оркестра утверждают мрачную непреложность ведущего образа симфонии.

Вторая часть. Molto vivace

В скерцо образы действительности предстают в необычном для Бетховена мрачно-демоническом аспекте. В безудержно головокружительном движении как бы воплощается драматизм стремительного бега жизни.

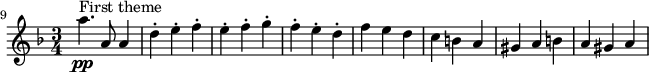

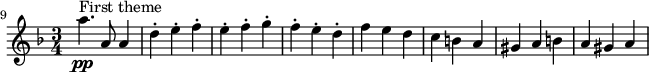

Есть нечто внутренне общее в неумолимости властных возгласов начальной темы скерцо с лейтмотивом Пятой симфонии. В обоих случаях от начальных унисонов с резко очерченным ритмом исходит сила, насыщающая последующее движение и развитие; как в Пятой, в скерцо Девятой симфонии ритмический мотив обладает значением и смыслом некоего эпиграфа. От него берет начало собственно тема; с размеренной периодичностью она «бесконечно» канонически повторяется с неотвязностью преследующей мысли:

Еще более жестко начальный мотив звучит, когда превращается в ритмический фон для второй темы. Ее появление — это своего рода кульминация основного образа. Вся энергия и сила концентрируются в компактном звучании всего оркестра: фугированное развитие «собирается» в аккордовые вертикали. Мажорный лад (F-dur) фиксирует значительность этого момента:

Особой оригинальностью отличается строение скерцо. Сущность его — в трансформации сложной трехчастной формы, крайние части которой написаны в развернутой сонатной форме, а средний, контрастный, раздел представляет собой простую трехчастную форму. Драматизму крайних частей противопоставлена пасторальная идилличность средней части — трио. Оно написано в спокойной, даже несколько шутливой жанровой манере, дышит ароматом сельского пейзажа и простотой крестьянской песни. Народность этого образа, его ясность и чистота рассеивают окружающий сумрак, освещают дорогу к далекой, но уже видимой цели. Не случайно так близки напев трио и гимн радости в финале:

Третья часть. Adagio molto e cantabile

Все мучительное и тревожное, что волновало раньше, отодвигается, как бы уходит в прошлое. Духовная просветленность и целомудрие, философская созерцательность характеризуют облик Adagio, особенно первой темы. Ее возвышенный лиризм полон благостного покоя. Медлительно, на глубоком дыхании развертывается мелодия:

Тональный сдвиг из B-dur в D-dur, очевидно, призван оттенить переход к более теплым краскам второй темы (Andante moderato). Задумчиво-мечтательная, несколько более подвижная, она проходит в ритме медленного танца:

Эти две темы — основа для цепи последующих вариаций. Двойные вариации Adagio Девятой несколько отличаются от двойных вариаций в Andante Пятой симфонии. В Пятой тональный план первого проведения тем (As-dur с коротким сдвигом в C-dur во второй теме) сохраняется почти полностью на протяжении всей части. В Девятой различные оттенки лирики двух тем подчеркнуты разной тональной окраской, различиями в темповых обозначениях и метроритмической структуре. Бетховен не придерживается здесь одной, избранной для всего вариационного цикла, тональности — B-dur: есть вариация в Es-dur — на первую тему, в G-dur — на вторую тему. Вместе с тем путь сближения и взаимопроникновения обеих тем весьма интенсивен и начинается сразу после их показа.

Первая вариация на первую тему «заимствует» от второй темы фактуру, тип фигурации, характерную интонацию задержания:

Единство фактуры, отсутствие завершающих каденций скрадывают переходы от одной вариации к другой, благоприятствуют слитности и целостности формы, ощущению непрерывности, текучести музыкальной ткани.

В расширенной последней вариации (от L’istesso tempo) большому развитию подвергается первая тема. Перенесенная в высокие регистры деревянных духовых инструментов, обволакиваемая легкой дымкой фигурации у скрипок, эта тема постепенно приобретает характер отрешенной созерцательности. Но незадолго до конца спокойную тишину звучания неожиданно взрывают громкие сигналы фанфар. Они дважды прорезывают воздушную фактуру вариаций. Программно этот момент можно истолковать как призыв к действию, к борьбе. Так в мир возвышенной поэзии властно вторгается жизнь, и с последними звуками Adagio уносятся мечты и поэтические видения.

Четвертая часть. Финал. Presto

В финале — итоге всей симфонии — Бетховен, конкретизируя идею произведения, использует текст «Оды к радости» Ф. Шиллера. Увлечение «Одой» Бетховен пронес через всю свою творческую жизнь. Еще в Бонне, в 1792 году он намеревался положить на музыку весь текст Шиллера целиком. Но теперь, работая над самым зрелым своим творением, Бетховен изменил план шиллеровского произведения и, отобрав нужные строфы и строки, «сумел из … лирических излияний Шиллера создать последовательное развитие, единый и цельный организм…» (Р. Роллан).

При этом гимн радости превратился у Бетховена в гимн свободе. Вот как пишет об этом А. Г. Рубинштейн: «Не верю я также, что эта последняя часть есть «ода к радости», считаю ее одой к свободе. Говорят, что Шиллер по требованию цензуры должен был заменить слово свобода словом радость, и что Бетховен это знал, я в этом вполне уверен. Радость не приобретается, она приходит и она тут, но свобода должна быть приобретена… кроме того, свобода есть весьма серьезная вещь, и потому тема этой оды столь серьезного характера…».

Хоровая часть финала предваряется инструментальным прологом. Грандиозное полотно финала вмещает и «взгляд назад» — ретроспективное обобщение пройденного пути, — и всю полноту величия достигнутой победы. Такой замысел породил сложность строения, заставив Бетховена, по словам Р. Роллана, использовать «самые разнообразные музыкальные жанры: речитативы, песню, хорал, вариации, инструментальное фугато и двойную хоровую фугу, смешав стили Палестрины, Генделя и т. д. И из этих разнородных элементов он выковал могучее единство».

Принцип композиции четвертой части (действительно легко распадающейся на большое количество эпизодов) до известной степени можно уподобить композициям больших оперных финалов, где появление нового персонажа, включающегося в действие, соответственно отражается в музыке на изменении тематического материала, смене тональности, фактуры, оркестровки.

Цементирует все эпизоды финала тема-гимн, воплощающая центральный образ шиллеровской оды, — тема радости. Она получает вариационное развитие в оркестре и в хоре. Объединяющее значение имеет и тональный «каркас», который опирается на принятый для всей симфонии круг тональностей: d-moll, D-dur, B-dur, G-dur, D-dur.

Драматическим диалогом начинается оркестровое вступление четвертой части — своеобразное преддверие, пролог. Неистовый угрожающий гнев слышен во фразах оркестра — «фанфары ужаса» (по выражению Р. Вагнера) — это трансформированная главная тема первой части:

Содержанно и сурово звучит в ответ речитатив виолончелей и контрабасов:

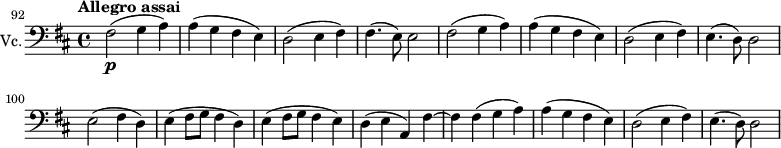

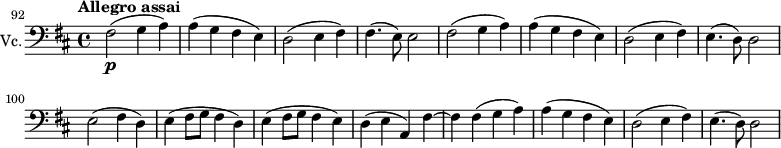

Воскрешая в памяти пройденный путь, Бетховен напоминает начальные темы предыдущих частей: таинственно-мрачное вступление первого Allegro, стремительную тему скерцо, медленно проплывающую тему Adagio cantabile. Каждой теме отвечает речитатив басов, как бы отбрасывающий видения прошлого. Но тени минувшего заставляют сильнее желать и острее чувствовать близость освобождения. И как предвестник великого торжества, возникает издалека в приглушенном звучании виолончелей и контрабасов новая тема — тема радости:

Мелодия гимна, почти элементарная по своему складу, звучит, по выражению Серова, «всенародным мотивом». Создание ее явилось результатом длительного многолетнего труда. Мелодия эта, говорит Р. Роллан, была «навязчивой идеей юности» Бетховена, ее первые варианты неоднократно встречаются в произведениях разного времени и разных жанров (Можно назвать песню «Вздохи отвергнутого и взаимная любовь» (1794), Фантазию для фортепиано, хора и оркестра» (1808); эскизы темы Бетховен набрасывал в 1804, 1812 и, наконец, в 1822 году.).

Первое проведение темы у виолончелей и контрабасов вызывает цепь вариаций, этот первый инструментальный цикл завершается полным оркестровым звучанием гимна:

Вновь вторгаются «фанфары ужаса», знаменующие начало вокально-инструментального раздела финала. «О, братья, не надо печали» — возглашает баритон solo.

Тема радости передается теперь хору, и цикл хоровых вариаций вливается в общий поток симфонического развития.

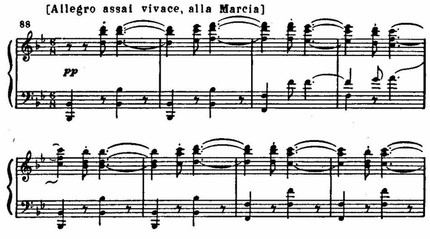

Alia Marcia — новая фаза развития основной темы. Меняется весь музыкальный план: тональность (B-dur), размер, темп, оркестровка, хоровой состав. Из оркестра почти полностью выключаются струнные, звучит «весь арсенал военной музыки», а в хоре остаются только мужские голоса. Они звучат, как «гимн молодой, воинственной радости, марш наступления, марсельеза» (Р. Роллан):

Этот раздел подводит через постепенное нарастание к мощной хоровой кульминации в D-dur, когда хор, поддерживаемый всем оркестром (тема в увеличении), в строгом ритме чеканит слова: «Радость! Юной жизни пламя»:

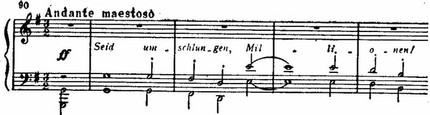

Торжество завоеванной свободы впервые прозвучало с такой непоколебимой уверенностью. Всеобщность этого чувства утверждается в суровом хоральном песнопении Andante maestoso:

Прямой призыв «Обнимитесь, миллионы» передается новому разделу — Allegro energico. В двойной фуге одновременно звучат обе темы: хорал из Andante maestoso и тема радости:

Мощное движение разрастается в грандиозный апофеоз, которым увенчивается не только Девятая симфония, но и все творчество Бетховена. По словам Р. Роллана, этим произведением Бетховен «воздвиг себе памятник, который с полным правом можно считать единственным в своем роде».

В. Галацкая

Десять лет отделяют Девятую симфонию d-moll – D-Dur (ор. 125, 1822 — 1824) от предшествующих симфоний. В этом самом грандиозном из всех его инструментальных произведений композитор в последний раз возвратился к теме героической борьбы, которая красной нитью проходит через все его творчество.

Хоровой финал симфонии на текст оды Шиллера «К радости» исчерпывающе раскрывает идею произведения. В свое время цензурные условия заставили поэта заменить подлинное название оды «К свободе» более нейтральным — «К радости». Бетховен подверг значительной переработке текст, подчеркнув в нем революционное начало.

Симфония прозвучала как смелый вызов реакции, как напоминание о том, что передовые идеалы продолжают жить и в мрачные времена социального угнетения и насилия, что человек-боец не одинок и в объединении лежит путь к свободе. Никогда еще Бетховен не достигал подобной силы выражения оптимистического чувства, подобной революционной страстности.

Идея воплощения оды Шиллера в музыке впервые возникла у Бетховена еще в девятнадцатилетнем возрасте. Тематизм Девятой симфонии тоже подготавливался десятилетиями (Замысел создать симфонию в d-moll’ной тональности возник в боннский период. Интонации главной темы прозвучали во вступлении ко Второй симфонии в 1802 году. Первый обнаруженный набросок начала Девятой относится к 1809 году, он встречается еще раз в записях 1817 года. В тетрадях 1815 и 1817 годов попадаются разрозненные эскизы тем будущей второй части Девятой симфонии. Варианты темы хорового финала появляются в разных произведениях на протяжении тридцати лет. Таковы мелодии хоровой «компанейской песни» «Взаимная любовь» (1794), одна из тем фантазии для фортепиано, хора в оркестра (1808).). И только в 1822 году, когда, преодолев творческий кризис, Бетховен приступил непосредственно к сочинению, идея шиллеровской оды слилась у него с представлениями о d-moll’ной симфонии и с музыкальной темой, предвосхищающей тему радости.

Глубокий анализ идейно-философского содержания Девятой симфонии и ее выразительных средств дал А. Н. Серов в своей классической работе «Девятая симфония Бетховена, ее склад и смысл» (1868).

Драматургия этой симфонии, воплощающая типичную для Бетховена идею «от мрака к свету», выражена в такой последовательной форме, что финал является не только кульминацией цикла, как в Пятой, но и образно-смысловым центром всего произведения. Первые ее три части образуют словно инструментальный пролог к хоровой кантате на текст оды «К радости». Стремясь максимально последовательно дать движение от мрака к просветлению и радости, композитор даже нарушил установившуюся структуру симфонического цикла, поместив медленную часть между скерцо и финалом (Этот прием, новый в симфонической музыке, уже был использован Моцартом в g-moll’ном квинтете, который во многом предвосхитил драматургию бетховенских циклов.). Симфоническое развитие в целом отмечено большой сложностью, внутренним напряжением. Несмотря на родство общей идеи симфонии с замыслами «Героической» и Пятой симфоний, оно оригинально и необычно от начала до конца.

«Это первое мрачное эпическое вступление пахнет кровавыми деяниями терроризма. Царство свободы и единения должно быть завоёвано. Все ужасы войны – подкладка для этой первой части. Она ими чревата в каждой строчке. Эти темные страницы служат художественным контрастом для отдалённого еще Эллизия, но, кроме писательского приёма, это вместе – глубочайшее философское воплощение в звуках тёмных страниц истории человечества, страниц вечной борьбы, вечных сомнений, вечного уныния, вечной печали, среди которых радость, счастье мелькают мимолётным, как молния, проблеском». Так характеризовал Серов содержание первой части Девятой симфонии.

Однако в этом могучем Allegro Бетховен подчеркнул не только уныние, печаль и мрак. С первых звуков главной темы, — суровой, лаконичной, драматичной – возникает чувство страстного, упорного сопротивления.

Драматизм, определяющий собой все содержание симфонии, с необычной силой выражен уже в главной теме:

Ее интонации проникают и в другие части произведения объединяя между собой резко контрастные эпизоды цикла.

Противопоставление суровых мелодических контуров (а) интонациям мотива жалобы (б) создает предельно контрастный эффект. Тревожный мотив на звуке ля (в), ритм которого напоминает маршевую барабанную дробь, заставляет слух насторожиться. Эти три мотива служат основным интонационным источником грандиозного сонатного Allegro. В процессе развития неизменно усиливается значение трагических образов. Как и в «Героической симфонии», движение развивается по принципу «нарастающих волн», на основе непрерывного преодоления препятствий. Однако в Девятой симфонии образы борьбы и сопротивления показаны еще более устремленно, в еще более драматичном аспекте. Первая часть симфонии заканчивается не просветлением (как в «Героической»), а суровым траурным маршем.

В этом сонатном Allegro Бетховен нашел множество новых приемов огромной художественной силы. Необычны и остро выразительны подход к главной теме, ее зарождение в тонально неопределенном, «вибрирующем» звучании квинты (тремоло у виолончелей, скрипок и валторны):

Поражает своей интенсивностью колоссальная разработка, сочетающая сложнейшее мотивное и полифоническое развитие, всецело основывающееся на интонационных элементах главной темы. Видоизмененная полифонизированная реприза воспринимается как грандиозное завершение разработки и отличается предельной динамической мощью:

Необычны для классических симфоний и тональные центры d-moll – B-dur. Их терцовое соотношение и ладовый конфликт пройдут через всю симфонию вплоть до финала. Особой художественной силой обладает поступь мерного шага — «нечто вроде марша, ритм суровый, боевой» (Серов), который проходит через всю первую часть, достигая максимального эффекта в траурно-героической коде:

Как главная тема симфонии, так и вся музыка сонатного Allegro отличается скульптурной рельефностью и монументальностью.

Вторая часть — скерцо гигантских размеров. Его замысел потребовал огромного расширения и драматизации традиционной трехчастиости. Тревожное, взволнованное настроение проникает в крайние разделы. Острая ритмическая пульсация, приёмы фугато в мелодическом развитии и, наконец, предельно динамизированная форма создают ощущение громадного наростания. Особенно интересны сонатные черты формы. Здесь есть главная партия, построенная как динамическая трехчастная форма с разработочной серединой:

Ясно выражена контрастная побочная тема жанрового склада:

Столь же определенно очерчены разработка и реприза.

Средний эпизод выражает мир идиллии и мечты. Он противопоставляется взволнованному движению обрамляющих частей. В прозрачной музыке эпизода господствует песенно-танцевальное начало. А. Н. Серов усматривал в ней родство с интонациями славянского фольклора.

Третья часть, Adagio molto е cantabile, принадлежит к вершинам лирического вдохновения Бетховена. Здесь особенно непосредственно проявляется связь Девятой симфонии с поздним бетховенским стилем. Глубина и возвышенность этой музыки, ее полимелодическая фактура, текучесть мелодии и вариационное развитие предвосхищают поздние квартеты Бетховена. Типично и противопоставление двух полярно контрастных тем: сосредоточенно-возвышенной (B-dur, Adagio), содержащей многие выразительные приемы квартетного стиля, и «вальсовой», песенной (D-dur, Andante), отличающейся редким мелодическим обаянием и лирической непосредственностью:

Вторая тема дважды появляется между вариациями главной и оттеняет, наподобие контрастного эпизода, господствующее настроение философского раздумья. Лишь на миг, как бы извне вторгается краткий фанфарно-призывный мотив, связанный с интонациями главной темы симфонии:

Но он бесследно растворяется в текучей мелодической фигурации.

Драматизму, сумрачным тонам, углубленным настроениям первых трех частей противопоставлена музыка, полная радости и света.

В финале классицистская симфония впервые выходит за рамки чисто инструментальных средств: в момент героической кульминации Бетховен вводит голоса и хор. Но подход к этому моменту постепенный, его появление оправдано предварительным сложным развитием.

Финал членится на два крупных раздела.

В первом, инструментальном, разделе осуществляется переход к «царству света», к оде «К радости». «Фанфара ужаса» (Вагнер), интонационно родственная главной теме первой части симфонии, открывает этот раздел:

Как воспоминание о прошедшей борьбе проходят фрагменты тем предшествующих частей. Но инструментальный речитатив прерывает суровые и мрачные тона:

Первоначально Бетховен предполагал поручить речитатив певцам и даже набросал к нему слова. В них говорилось о поисках новых путей к радости (то есть к свободе) (Сохранились наброски этого текста. Первый речитатив исполнялся на слова: «Нет, это нам напоминало бы о нашем отчаянии. Сегодня торжественный день — он должен быть отпразднован пением и танцами». После Allegro ma non troppo (музыка начала первой части) следуют слова: «О нет, не надо этого, я требую иного, более приятного…» При мимолетном возвращении темы скерцо раздается возглас: «И этого не надо — это лишь шалость, что-нибудь лучшее, более бодрое…» При начальных звуках Adagio голоса возражают: «И это также чересчур чувствительно: нужно искать чего-нибудь энергичного. Пожалуй, я сам спою — тогда лишь вторьте мне».). Но вторжение человеческого голоса показалось композитору здесь слишком неподготовленным, и он передал речитатив виолончелям.

Наконец, после длительных исканий, появляется тема радости:

Эта гениально простая тема обобщает образы и интонации, которые в предшествующих частях характеризовали проблески света.

Они прозвучали впервые в побочной партии первой части. На фоне сгущенных мрачных красок эта тема служила единственным контрастным моментом:

Подобные же интонационные образования легли в основу мимолетного жизнерадостного эпизода в зловещем скерцо — его побочной теме. Светлая D-dur’ная тема Adagio также содержит намеки на интонации «темы радости». Наконец, весь солнечный, идиллический эпизод второй части пронизан сходными мелодическими оборотами:

Плавная и простая песенная мелодия народного танца, ритм энергичной поступи придают «теме радости» характер гимна.

Тема финала постепенно разрастается, подобно тому как развивалась маршевая тема Allegretto Седьмой симфонии. Но движение здесь отличается большой масштабностью и мощью. Полифоническое обрастание мелодии, сгущение оркестровых красок, увеличение объема звуков приводят к огромному динамическому подъему. Достигнув вершины, Бетховен внезапно возвращается к исходному построению первого раздела.

Второй раздел, инструментально-хоровой, начинается с повторения «интонаций ужаса», но здесь уже вступают человеческие голоса. Знакомый речитатив звучит со словами, сочиненными Бетховеном: «О братья, не надо этих звуков, дайте нам услышать более приятные, более радостные». С этого момента начинается грандиозная хоровая ода «К радости».

Форма громадного хорового финала уникальна в симфонической литературе: она отличается исключительной сложностью, объединяя в себе черты вариаций, рондо, фуги и сонаты.

Вариационное развитие воспринимается наиболее непосредственно. Тема последовательно преобразуется, поочерёдно принимая характер какого-либо народного жанра: марша, песни, хорового гимна, танца и т.д.:

В этой линии развития дополнительно намечается форма двойных вариаций. Второй темой становится B-dur’ная, маршевая (пример 68 в). Производная от темы радости, она резко контрастирует с ней настроением настороженной тревоги (уводящим к мрачному образу «барабанной дроби» в главной теме первой часта). Ряд формально композиционных приемов указывает на самостоятельный характер этой темы (тональность В-dur, которая на протяжении всего цикла образует второй тональный центр, относительная отдаленность мелодии от основной темы).

Между проведениями варьируемой темы Бетховен вводит богатый и многообразный материал. Некоторые эпизоды более или менее непосредственно связаны с темой радости, другие далеки от нее. Троекратное возвращение темы радости в ее ясной первоначальной форме создает бесспорный рондообразный эффект.

Самое значительное самостоятельное тематическое образование — новый эпизод философски-возвышенного склада. Будучи типичным для позднего Бетховена, он вместе с тем близок складу генделевской музыки. По ряду признаков (звучание оркестра, напоминающее орган, «архаические» последования в гармонии и т. д. и т. п.) это тематическое построение вызывает ассоциации и со старинной хоровой церковной музыкой, которая издавна сложилась как выразитель молитвенного настроения, углубленной отвлеченной мысли:

В конце эта тема и «тема радости» образуют двойную фугу — кульминацию всей оды. Наконец, соотношение тематического материала и тональных центров позволяет утверждать, что музыке оды присущи и элементы сонатного развития (Сонатную форму можно представить следующим образом: вступление — Presto, d-moll. Главная партия — Allegro assai, «тема радости», D-dur Побочная — Allegro assai vivace alla marcia, B-dur. Разработка — модуляционное развитие, новый эпизод Adagio ma non troppo, ma divoto. Реприза — Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato, D-dur, с двойной фугой. Кода — Prestissimo, D-dur.).

Финал построен на грандиозных контрастах, на мощном развитии. Сочетание вокального, хорового и оркестрового звучания раздвигает границы художественной выразительности. В героическом заключении действительно чувствуется сила «миллионов».

Девятая симфония Бетховена вошла в историю мировой культуры как одно из величайших творений, выражающих гуманистические, свободолюбивые идеалы человечества. Ее влияние на искусство последующего времени огромно.

В. Конен

- Симфоническое творчество Бетховена →

реклама

вам может быть интересно

Публикации

| Symphony No. 9 | |

|---|---|

| Choral symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

A page (leaf 12 recto) from Beethoven’s manuscript | |

| Key | D minor |

| Opus | 125 |

| Period | Classical-Romantic (transitional) |

| Text | Friedrich Schiller’s «Ode to Joy» |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1822–1824 |

| Dedication | King Frederick William III of Prussia |

| Duration | about 70 minutes |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Orchestra with SATB chorus and soloists |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 7 May 1824 |

| Location | Theater am Kärntnertor, Vienna |

| Conductor | Michael Umlauf and Ludwig van Beethoven |

| Performers | Kärntnertor house orchestra, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde with soloists: Henriette Sontag (soprano), Caroline Unger (alto), Anton Haizinger (tenor), and Joseph Seipelt (bass) |

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, is a choral symphony, the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musicologists as Beethoven’s greatest work and one of the supreme achievements in the history of music.[1][2] One of the best-known works in common practice music,[1] it stands as one of the most frequently performed symphonies in the world.[3][4]

The Ninth was the first example of a major composer using voices in a symphony.[5] The final (4th) movement of the symphony features four vocal soloists and a chorus. The text was adapted from the «Ode to Joy», a poem written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and revised in 1803, with additional text written by Beethoven.

In 2001, Beethoven’s original, hand-written manuscript of the score, held by the Berlin State Library, was added to the Memory of the World Programme Heritage list established by the United Nations, becoming the first musical score so designated.[6]

History[edit]

Composition[edit]

The Philharmonic Society of London originally commissioned the symphony in 1817.[7] The main composition work was done between autumn 1822 and the completion of the autograph in February 1824.[8] The symphony emerged from other pieces by Beethoven that, while completed works in their own right, are also in some sense «sketches» (rough outlines) for the future symphony. The 1808 Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, basically a piano concerto movement, brings in a choir and vocal soloists near the end for the climax. The vocal forces sing a theme first played instrumentally, and this theme is reminiscent of the corresponding theme in the Ninth Symphony.

Going further back, an earlier version of the Choral Fantasy theme is found in the song «Gegenliebe» (Returned Love) for piano and high voice, which dates from before 1795.[9] According to Robert W. Gutman, Mozart’s Offertory in D minor, «Misericordias Domini», K. 222, written in 1775, contains a melody that foreshadows «Ode to Joy».[10]

Premiere[edit]

Although most of his major works had been premiered in Vienna, Beethoven was keen to have his latest composition performed in Berlin as soon as possible after finishing it, as he thought that musical taste in Vienna had become dominated by Italian composers such as Rossini.[11] When his friends and financiers heard this, they urged him to premiere the symphony in Vienna in the form of a petition signed by a number of prominent Viennese music patrons and performers.[11]

Beethoven was flattered by the adoration of Vienna, so the Ninth Symphony was premiered on 7 May 1824 in the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna along with the overture The Consecration of the House (Die Weihe des Hauses) and three parts of the Missa solemnis (the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei). This was the composer’s first onstage appearance in 12 years; the hall was packed with an eager audience and a number of musicians and figures in Vienna including Franz Schubert, Carl Czerny, and the Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich. [12][13]

The premiere of Symphony No. 9 involved the largest orchestra ever assembled by Beethoven[12] and required the combined efforts of the Kärntnertor house orchestra, the Vienna Music Society (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), and a select group of capable amateurs. While no complete list of premiere performers exists, many of Vienna’s most elite performers are known to have participated.[14][15]

The soprano and alto parts were sung by two famous young singers: Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger. German soprano Henriette Sontag was 18 years old when Beethoven personally recruited her to perform in the premiere of the Ninth.[16][17] Also personally recruited by Beethoven, 20-year-old contralto Caroline Unger, a native of Vienna, had gained critical praise in 1821 appearing in Rossini’s Tancredi. After performing in Beethoven’s 1824 premiere, Unger then found fame in Italy and Paris. Italian composers Donizetti and Bellini were known to have written roles specifically for her voice.[18] Anton Haizinger and Joseph Seipelt sang the tenor and bass/baritone parts, respectively.

Portrait of Beethoven in 1824, the year his Ninth Symphony was premiered. He was almost completely deaf by the time of its composition.

Caroline Unger, who sang the contralto part at the first performance and is credited with turning Beethoven to face the applauding audience

Although the performance was officially directed by Michael Umlauf, the theatre’s Kapellmeister, Beethoven shared the stage with him. However, two years earlier, Umlauf had watched as the composer’s attempt to conduct a dress rehearsal of his opera Fidelio ended in disaster. So this time, he instructed the singers and musicians to ignore the almost completely deaf Beethoven. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. He was turning the pages of his score and beating time for an orchestra he could not hear.[19]

There are a number of anecdotes about the premiere of the Ninth. Based on the testimony of the participants, there are suggestions that it was under-rehearsed (there were only two full rehearsals) and rather scrappy in execution.[20] On the other hand, the premiere was a great success. In any case, Beethoven was not to blame, as violinist Joseph Böhm recalled:

Beethoven himself conducted, that is, he stood in front of a conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts. —The actual direction was in [Louis] Duport’s[n 1] hands; we musicians followed his baton only.[21]

When the audience applauded—testimonies differ over whether at the end of the scherzo or symphony—Beethoven was several bars off and still conducting. Because of that, the contralto Caroline Unger walked over and turned Beethoven around to accept the audience’s cheers and applause. According to the critic for the Theater-Zeitung, «the public received the musical hero with the utmost respect and sympathy, listened to his wonderful, gigantic creations with the most absorbed attention and broke out in jubilant applause, often during sections, and repeatedly at the end of them.»[22] The audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and raised hands, so that Beethoven, who they knew could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovations.[23]

Editions[edit]

The first German edition was printed by B. Schott’s Söhne (Mainz) in 1826. The Breitkopf & Härtel edition dating from 1864 has been used widely by orchestras.[24] In 1997, Bärenreiter published an edition by Jonathan Del Mar.[25] According to Del Mar, this edition corrects nearly 3,000 mistakes in the Breitkopf edition, some of which were «remarkable».[26] David Levy, however, criticized this edition, saying that it could create «quite possibly false» traditions.[27] Breitkopf also published a new edition by Peter Hauschild in 2005.[28]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra. These are by far the largest forces needed for any Beethoven symphony; at the premiere, Beethoven augmented them further by assigning two players to each wind part.[29]

Form[edit]

The symphony is in four movements. The structure of each movement is as follows:[31]

-

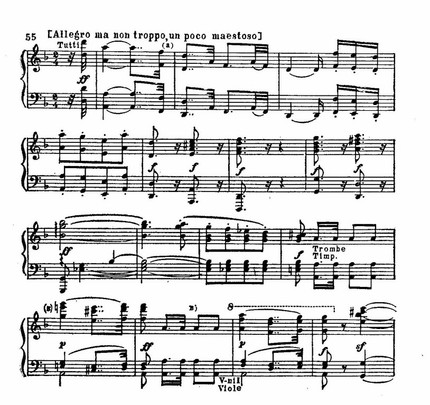

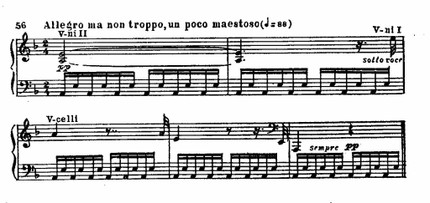

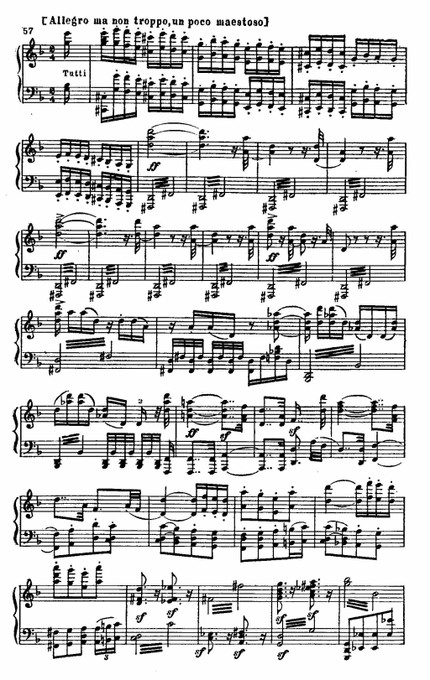

Tempo marking Meter Key Movement I Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso  = 88

= 88 2

4d Movement II Molto vivace  . = 116

. = 116 3

4d Presto  = 116

= 116 2

2D Molto vivace 3

4d Presto 2

2D Movement III Adagio molto e cantabile  = 60

= 60 4

4B♭ Andante moderato  = 63

= 63 3

4D Tempo I 4

4B♭ Andante moderato 3

4G Adagio 4

4E♭ Lo stesso tempo 12

8B♭ Movement IV Presto  . = 96[32]

. = 96[32] 3

4d Allegro assai  = 80

= 80 4

4D Presto («O Freunde») 3

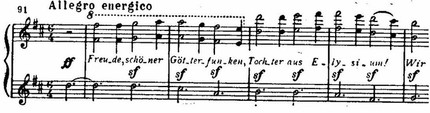

4d Allegro assai («Freude, schöner Götterfunken») 4

4D Alla marcia; Allegro assai vivace  . = 84 («Froh, wie seine Sonnen»)

. = 84 («Froh, wie seine Sonnen») 6

8B♭ Andante maestoso  = 72 («Seid umschlungen, Millionen!»)

= 72 («Seid umschlungen, Millionen!») 3

2G Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato  . = 84

. = 84

(«Freude, schöner Götterfunken» – «Seid umschlungen, Millionen!»)6

4D Allegro ma non tanto  = 120 («Freude, Tochter aus Elysium!»)

= 120 («Freude, Tochter aus Elysium!») 2

2D Prestissimo  = 132 («Seid umschlungen, Millionen!»)

= 132 («Seid umschlungen, Millionen!») 2

2D

Beethoven changes the usual pattern of Classical symphonies in placing the scherzo movement before the slow movement (in symphonies, slow movements are usually placed before scherzi).[33] This was the first time he did this in a symphony, although he had done so in some previous works, including the String Quartet Op. 18 no. 5, the «Archduke» piano trio Op. 97, the Hammerklavier piano sonata Op. 106. And Haydn, too, had used this arrangement in a number of his own works such as the String Quartet No. 30 in E♭ major, as did Mozart in three of the Haydn Quartets and the G minor String Quintet.

I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso[edit]

The first movement is in sonata form without an exposition repeat. It begins with open fifths (A and E) played pianissimo by tremolo strings, steadily building up until the first main theme in D minor at bar 17.[34]

The opening, with its perfect fifth quietly emerging, resembles the sound of an orchestra tuning up.[35]

At the outset of the recapitulation (which repeats the main melodic themes) in bar 301, the theme returns, this time played fortissimo and in D major, rather than D minor. The movement ends with a massive coda that takes up nearly a quarter of the movement, as in Beethoven’s Third and Fifth Symphonies.[36]

A typical performance lasts about 15 minutes.

II. Molto vivace[edit]

The second movement is a scherzo and trio. Like the first movement, the scherzo is in D minor, with the introduction bearing a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the first movement, a pattern also found in the Hammerklavier piano sonata, written a few years earlier. At times during the piece, Beethoven specifies one downbeat every three bars—perhaps because of the fast tempo—with the direction ritmo di tre battute (rhythm of three beats) and one beat every four bars with the direction ritmo di quattro battute (rhythm of four beats). Normally, a scherzo is in triple time. Beethoven wrote this piece in triple time but punctuated it in a way that, when coupled with the tempo, makes it sound as if it is in quadruple time.[37]

While adhering to the standard compound ternary design (three-part structure) of a dance movement (scherzo-trio-scherzo or minuet-trio-minuet), the scherzo section has an elaborate internal structure; it is a complete sonata form. Within this sonata form, the first group of the exposition (the statement of the main melodic themes) starts out with a fugue in D minor on the subject below.[37]

For the second subject, it modulates to the unusual key of C major. The exposition then repeats before a short development section, where Beethoven explores other ideas. The recapitulation (repeating of the melodic themes heard in the opening of the movement) further develops the exposition’s themes, also containing timpani solos. A new development section leads to the repeat of the recapitulation, and the scherzo concludes with a brief codetta.[37]

The contrasting trio section is in D major and in duple time. The trio is the first time the trombones play. Following the trio, the second occurrence of the scherzo, unlike the first, plays through without any repetition, after which there is a brief reprise of the trio, and the movement ends with an abrupt coda.[37]

The duration of the movement is about 12 minutes, but this may vary depending on whether two (frequently omitted) repeats are played.

III. Adagio molto e cantabile[edit]

The third movement is a lyrical, slow movement in B♭ major—a minor sixth away from the symphony’s main key of D minor. It is in a double variation form,[38] with each pair of variations progressively elaborating the rhythm and melodic ideas. The first variation, like the theme, is in 4

4 time, the second in 12

8. The variations are separated by passages in 3

4, the first in D major, the second in G major, the third in E♭ major, and the fourth in B major. The final variation is twice interrupted by episodes in which loud fanfares from the full orchestra are answered by octaves by the first violins. A prominent French horn solo is assigned to the fourth player.[39]

A performance lasts about 16 minutes.

IV. Finale[edit]

The choral finale is Beethoven’s musical representation of universal brotherhood based on the «Ode to Joy» theme and is in theme and variations form.

The movement starts with an introduction in which musical material from each of the preceding three movements—though none are literal quotations of previous music[40]—are successively presented and then dismissed by instrumental recitatives played by the low strings. Following this, the «Ode to Joy» theme is finally introduced by the cellos and double basses. After three instrumental variations on this theme, the human voice is presented for the first time in the symphony by the baritone soloist, who sings words written by Beethoven himself: »O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!’ Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen, und freudenvollere.» («Oh friends, not these sounds! Let us instead strike up more pleasing and more joyful ones!»).

At about 24 minutes in length, the last movement is the longest of the four movements. Indeed, it is longer than some entire symphonies of the Classical era. Its form has been disputed by musicologists, as Nicholas Cook explains:

Beethoven had difficulty describing the finale himself; in letters to publishers, he said that it was like his Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, only on a much grander scale. We might call it a cantata constructed round a series of variations on the «Joy» theme. But this is rather a loose formulation, at least by comparison with the way in which many twentieth-century critics have tried to codify the movement’s form. Thus there have been interminable arguments as to whether it should be seen as a kind of sonata form (with the «Turkish» music of bar 331, which is in B♭ major, functioning as a kind of second group), or a kind of concerto form (with bars 1–207 and 208–330 together making up a double exposition), or even a conflation of four symphonic movements into one (with bars 331–594 representing a Scherzo, and bars 595–654 a slow movement). The reason these arguments are interminable is that each interpretation contributes something to the understanding of the movement, but does not represent the whole story.[41]

Cook gives the following table describing the form of the movement:[42]

| Bar | Key | Stanza | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1[n 3] | d | Introduction with instrumental recitative and review of movements 1–3 | |

| 92 | 92 | D | «Joy» theme | |

| 116 | 116 | «Joy» variation 1 | ||

| 140 | 140 | «Joy» variation 2 | ||

| 164 | 164 | «Joy» variation 3, with extension | ||

| 208 | 1 | d | Introduction with vocal recitative | |

| 241 | 4 | D | V.1 | «Joy» variation 4 |

| 269 | 33 | V.2 | «Joy» variation 5 | |

| 297 | 61 | V.3 | «Joy» variation 6, with extension providing transition to | |

| 331 | 1 | B♭ | Introduction to | |

| 343 | 13 | «Joy» variation 7 («Turkish march») | ||

| 375 | 45 | C.4 | «Joy» variation 8, with extension | |

| 431 | 101 | Fugato episode based on «Joy» theme | ||

| 543 | 213 | D | V.1 | «Joy» variation 9 |

| 595 | 1 | G | C.1 | Episode: «Seid umschlungen» |

| 627 | 76 | g | C.3 | Episode: «Ihr stürzt nieder» |

| 655 | 1 | D | V.1, C.3 | Double fugue (based on «Joy» and «Seid umschlungen» themes) |

| 730 | 76 | C.3 | Episode: «Ihr stürzt nieder» | |

| 745 | 91 | C.1 | ||

| 763 | 1 | D | V.1 | Coda figure 1 (based on «Joy» theme) |

| 832 | 70 | Cadenza | ||

| 851 | 1 | D | C.1 | Coda figure 2 |

| 904 | 54 | V.1 | ||

| 920 | 70 | Coda figure 3 (based on «Joy» theme) |

In line with Cook’s remarks, Charles Rosen characterizes the final movement as a symphony within a symphony, played without interruption.[43] This «inner symphony» follows the same overall pattern as the Ninth Symphony as a whole, with four «movements»:

- Theme and variations with slow introduction. The main theme, first in the cellos and basses, is later recapitulated by voices.

- Scherzo in a 6

8 military style. It begins at Alla marcia (bar 331 — 594) and concludes with a 6

8 variation of the main theme with chorus. - Slow section with a new theme on the text «Seid umschlungen, Millionen!» It begins at Andante maestoso (bar 595 — 654).

- Fugato finale on the themes of the first and third «movements». It begins at Allegro energico (bar 655 — 762), and two canons on main theme and «Seid unschlungen, Millionen!» respectively. It begins at Allegro ma non tanto (bar 763 — 940).

Rosen notes that the movement can also be analysed as a set of variations and simultaneously as a concerto sonata form with double exposition (with the fugato acting both as a development section and the second tutti of the concerto).[43]

Text of the fourth movement[edit]

The text is largely taken from Friedrich Schiller’s «Ode to Joy», with a few additional introductory words written specifically by Beethoven (shown in italics).[44] The text, without repeats, is shown below, with a translation into English.[45] The score includes many repeats. For the full libretto, including all repetitions, see German Wikisource.[46]

| O Freunde, nicht diese Töne! | Oh friends, not these sounds! |

| Freude! | Joy! |

| Freude, schöner Götterfunken | Joy, beautiful spark of divinity, |

| Wem der große Wurf gelungen, | Whoever has been lucky enough |

| Freude trinken alle Wesen | Every creature drinks in joy |

| Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen | Gladly, just as His suns hurtle |

| Seid umschlungen, Millionen! Ihr stürzt nieder, Millionen? | Be embraced, you millions! Do you bow down before Him, you millions? |

Towards the end of the movement, the choir sings the last four lines of the main theme, concluding with «Alle Menschen» before the soloists sing for one last time the song of joy at a slower tempo. The chorus repeats parts of «Seid umschlungen, Millionen!», then quietly sings, «Tochter aus Elysium», and finally, «Freude, schöner Götterfunken, Götterfunken!».[46]

Reception[edit]

The symphony was dedicated to the King of Prussia, Frederick William III.[47]

Music critics almost universally consider the Ninth Symphony one of Beethoven’s greatest works, and among the greatest musical works ever written.[1][2] The finale, however, has had its detractors: «[e]arly critics rejected [the finale] as cryptic and eccentric, the product of a deaf and ageing composer.»[1] Verdi admired the first three movements but lamented what he saw as the bad writing for the voices in the last movement:

The alpha and omega is Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, marvellous in the first three movements, very badly set in the last. No one will ever approach the sublimity of the first movement, but it will be an easy task to write as badly for voices as in the last movement. And supported by the authority of Beethoven, they will all shout: «That’s the way to do it…»[48]

— Giuseppe Verdi, 1878

Performance challenges[edit]

Handwritten page of the fourth movement

Metronome markings[edit]

Conductors in the historically informed performance movement, notably Roger Norrington,[49] have used Beethoven’s suggested tempos, to mixed reviews. Benjamin Zander has made a case for following Beethoven’s metronome markings, both in writing[26] and in performances with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and Philharmonia Orchestra of London.[50][51] Beethoven’s metronome still exists and was tested and found accurate,[52] but the original heavy weight (whose position is vital to its accuracy) is missing and many musicians have considered his metronome marks to be unacceptably high.[53]

Re-orchestrations and alterations[edit]

A number of conductors have made alterations in the instrumentation of the symphony. Notably, Richard Wagner doubled many woodwind passages, a modification greatly extended by Gustav Mahler,[54] who revised the orchestration of the Ninth to make it sound like what he believed Beethoven would have wanted if given a modern orchestra.[55] Wagner’s Dresden performance of 1864 was the first to place the chorus and the solo singers behind the orchestra as has since become standard; previous conductors placed them between the orchestra and the audience.[54]

2nd bassoon doubling basses in the finale[edit]

Beethoven’s indication that the 2nd bassoon should double the basses in bars 115–164 of the finale was not included in the Breitkopf & Härtel parts, though it was included in the full score.[56]

Notable performances and recordings[edit]

The British premiere of the symphony was presented on 21 March 1825 by its commissioners, the Philharmonic Society of London, at its Argyll Rooms conducted by Sir George Smart and with the choral part sung in Italian. The American premiere was presented on 20 May 1846 by the newly formed New York Philharmonic at Castle Garden (in an attempt to raise funds for a new concert hall), conducted by the English-born George Loder, with the choral part translated into English for the first time.[57] Leopold Stokowski’s 1934 Philadelphia Orchestra[58] and 1941 NBC Symphony Orchestra recordings also used English lyrics in the fourth movement.[59]

Richard Wagner inaugurated his Bayreuth Festspielhaus by conducting the Ninth; since then it is traditional to open each Bayreuth Festival with a performance of the Ninth. Following the festival’s temporary suspension after World War II, Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra reinaugurated it with a performance of the Ninth.[60][61]

Leonard Bernstein conducted a version of the Ninth at the Schauspielhaus in East Berlin, with Freiheit (Freedom) replacing Freude (Joy), to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall during Christmas 1989.[62] This concert was performed by an orchestra and chorus made up of many nationalities: from East and West Germany, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, the Chorus of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and members of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden, the Philharmonischer Kinderchor Dresden (Philharmonic Children’s Choir Dresden); from the Soviet Union, members of the orchestra of the Kirov Theatre; from the United Kingdom, members of the London Symphony Orchestra; from the US, members of the New York Philharmonic; and from France, members of the Orchestre de Paris. Soloists were June Anderson, soprano, Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano, Klaus König, tenor, and Jan-Hendrik Rootering, bass.[63] It was the last time that Bernstein conducted the symphony; he died ten months later.

In 1998, Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa conducted the fourth movement for the 1998 Winter Olympics opening ceremony, with six different choirs simultaneously singing from Japan, Germany, South Africa, China, the United States, and Australia.[64]

Since the late 20th century, the Ninth has been recorded regularly by period performers, including Roger Norrington, Christopher Hogwood, and Sir John Eliot Gardiner.

The BBC Proms Youth Choir performed the piece alongside Georg Solti’s UNESCO World Orchestra for Peace at the Royal Albert Hall during the 2018 Proms at Prom 9, titled «War & Peace» as a commemoration to the centenary of the end of World War One.[65]

At 79 minutes, one of the longest Ninths recorded is Karl Böhm’s, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in 1981 with Jessye Norman and Plácido Domingo among the soloists.[66]

Influence[edit]

Plaque at building Ungargasse No. 5, Vienna. «Ludwig van Beethoven completed in this house during the winter of 1823/24 his Ninth Symphony. In memory of the centenary of its first performance on 7 May 1824 the Wiener Schubertbund dedicated this memorial plaque to the master and his work on 7 May 1924.»

Many later composers of the Romantic period and beyond were influenced by the Ninth Symphony.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the «Ode to Joy» theme from the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted «Any fool can see that!» Brahms’s first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as «Beethoven’s Tenth».

The Ninth Symphony influenced the forms that Anton Bruckner used for the movements of his symphonies. His Symphony No. 3 is in the same key (D minor) as Beethoven’s 9th and makes substantial use of thematic ideas from it. The slow movement of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 uses the A–B–A–B–A form found in the 3rd movement of Beethoven’s piece and takes various figurations from it.[67]

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (From the New World), Antonín Dvořák pays homage to the scherzo of this symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.[68]

Béla Bartók borrowed the opening motif of the scherzo from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to introduce the second movement (scherzo) in his own Four Orchestral Pieces, Op. 12 (Sz 51).[69][70]

Michael Tippett in his Third Symphony (1972) quotes the opening of the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth and then criticises the utopian understanding of the brotherhood of man as expressed in the Ode to Joy and instead stresses man’s capacity for both good and evil.[71]

In the film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek comments on the use of the Ode by Nazism, Bolshevism, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the East-West German Olympic team, Southern Rhodesia, Abimael Guzmán (leader of the Shining Path), and the Council of Europe and the European Union.[72]

Compact disc format[edit]