Людвиг ван Бетховен Симфония №7

Это произведение великого Бетховена, которым композитор гордился и называл любимым детищем, не сразу по достоинству было оценено его современниками. Симфонию № 7 поначалу охарактеризовали как «музыкальное сумасбродство» и «порождение возвышенного и больного ума», а её автора называли вполне созревшим для сумасшедшего дома. Прошло время и сочинением стали безудержно восторгаться, называя его «непостижимо прекрасным». Седьмой симфонии Людвига ван Бетховена предначертано было появиться на свет самой судьбой. Возможно апофеоз и всенародное ликование, слышимое в её музыке, указывает направление, приведшее гениального маэстро к его эпохальной оде «К радости», в которой прозвучало весьма важное воззвание ко всему человечеству: «Обнимитесь, миллионы!».

Историю создания «Симфонии №7» Бетховена, а также интересные факты и музыкальное содержание произведения читайте на нашей странице.

История создания

Когда Бетховену исполнилось двадцать шесть лет, его сразил страшный недуг, в результате которого он начал терять слух. Обращения к врачам самочувствие композитора не улучшили, и вскоре он понял, что прогрессирующая болезнь может привести к полной глухоте. Тягостные думы доводили Людвига до мысли о самоубийстве, однако взяв себя в руки, он начал ещё более усиленно заниматься композиторским творчеством.

Помимо этого у Бетховена даже появилось желание путешествовать, например, побывать в Италии, Англии и обязательно в Париже. Такую возможность он получил, когда пришло приглашение в 1811 году посетить Неаполь. Тем не менее воспользоваться им Людвиг не сумел, так как по настойчивому совету своего врача поехал не в Италию, а на чешский курорт Теплице.

Бетховен в июле прибыл туда не один, а с Францем Олива — молодым человеком с которым подружился в 1809 году. Пребывание на курорте композитору существенных улучшений здоровья не принесло, но оно надолго осталось в его памяти из-за встреч с интересными людьми. Там Людвиг познакомился с видными представителями немецкой интеллигенции, отличающимися передовыми убеждениями. Среди них особо выделялись лейтенант Варнгаген фон-Энзе и его невеста – талантливая писательница Рахиль Левин. Однако помимо этого были и другие встречи. Большое впечатление на Людвига произвело знакомство с очаровательной девушкой, талантливой певицей Амалией Зебальд. Прелестная юная особа своими внешними данными и красивым голосом сводила с ума не только Бетховена.

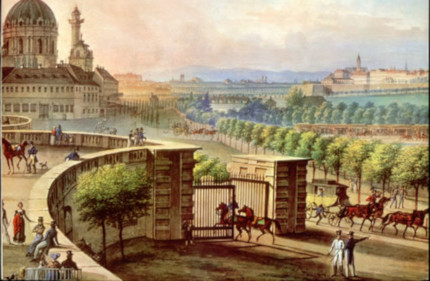

Вот такая вдохновляющая к творчеству обстановка и побудила композитора к созданию его седьмой симфонии. Однако писать её он начал не сразу, а через несколько месяцев по возвращении домой. В общей сложности на создание этого произведения композитору потребовалось чуть более пяти месяцев. Симфония была завершена в начале мая 1812 года, а её премьерное исполнение состоялось лишь через полтора года: в декабре 1813 года. Это был благотворительный концерт, прошедший в зале Венского университета в пользу солдат, получивших увечья в борьбе с наполеоновскими завоевателями.

Интересные факты

- Седьмую симфонию Людвиг ван Бетховен посвятил меценату, коллекционеру и банкиру графу Морицу Кристиану Иоганну фон Фрису.

- Современники Бетховена укоряли композитора за его седьмую симфонию, поясняя, что такая «простонародная» музыка недостойна высокого жанра.

- Премьерное исполнение «Симфонии № 7» Бетховена состоялось на благотворительном концерте в зале Университета города Вены. Оркестром дирижировал автор, а собранные деньги пошли на реабилитацию воинов-инвалидов. Однако исполнение симфонии на публику особого впечатления не произвело, а вот восторженного признания было удостоено сочинение, которое было создано композитором «на скорую руку». Это, как говорили, недостойное великого Бетховена произведение называлось «Победа Веллингтона, или Битва при Виттории». Шумная батальная музыкальная картина имела настолько потрясающий успех, что публикой для солдат было пожертвовано четыре тысячи гульденов, что по тем временам считалось невероятной суммой.

- Следует отметить, что над седьмой и восьмой симфониями Бетховен работал параллельно и закончил их практически одновременно. Создание этих произведений тесно связано с пребыванием композитора на чешском курорте «Теплице» в 1811 году. На следующее лето Людвиг вновь приехал в это удивительное место, славящееся целебными горячими источниками, и познакомился там с Иоганном Вольфгангом фон Гёте. Стоит отметить, что из-за строптивого характера Бетховена отношения между великими людьми так и не заладились.

- В первый раз Бетховен поехал в Теплице вместе с Францем Олива. Этот молодой человек, служивший обыкновенным бухгалтером, очень нежно и терпеливо относился к Людвигу. Композитор, имея сложный характер, мог вспылить на него, обозвать «неблагодарным негодяем» и прогнать вон. Однако Франц стойко выдерживал все оскорбления композитора, который был его кумиром и всегда, несмотря на обиды, приходил ему на помощь. Такая своеобразная дружба продолжалась до 1820 года, пока Франц не уехал в Россию.

- Седьмая симфония Бетховена является весьма известным произведением гениального маэстро, поэтому многие кинорежиссёры с большим удовольствием вставляют фрагменты в саундтреки своих фильмов. Вот некоторые из них: «Бетховен. Живи у меня» (Канада 1992), «Необратимость» (Франция 2002), «Король говорит!» (Великобритания, США, Австралия 2010), «Зардоз» (Ирландия, США 1974).

- Особой популярностью пользуется вторая часть «Симфонии №7» — «Allegretto». Эту композицию часто исполняют отдельно от всего произведения. Например её скорбное звучание сопровождало первую общеевропейскую траурную церемонию – прощание с бывшим канцлером ФРГ Гельмутом Колем в Страсбурге 1 июля 2017 года.

Содержание Симфонии №7 Бетховена

Симфония № 7 (A-dur) представляет собой четырёхчастную композицию, начинающуюся с величественного развёрнутого вступления (Poco sostenuto). В нём убедительные оркестровые аккорды гармонично сочетаются с волшебным мотивом в исполнении гобоя и тихими шуршащими гаммообразными пассажами струнных, звучание которых впоследствии дорастает до фортиссимо. Затем вступает новая тема, которая своей маршевой ритмической упругостью и тембровыми контрастами создаёт впечатление необычайной объёмности. В дальнейшем она изобретательно преобразуется, а из её последнего звука «ми» зарождается главная партия экспозиции.

Первая часть – Vivace. Весь жизнерадостный по характеру, не имеющий драматических конфликтов, тематический материал части объединён единым ритмическим рисунком, поэтому главная партия и все последующие за ней темы, воспринимаются как целостное музыкальное полотно.

Главную партию, наполненную солнечным блеском и основанную на народных танцевальных мотивах, начинают флейты, а затем подхватывают гобои, это придаёт музыке черты простодушности и пасторальности. В последующем проведении темы, в котором участвует весь оркестр, звучание труб и валторн преображает музыку и предаёт ей героический настрой. Побочная партия, построенная на предыдущем лейтритме, звучит как продолжение главной. Также основанная на народно-танцевальных мелодиях, она изобилует красочными модуляциями и на кульминационном триумфальном взлёте подводит к тональности доминанты.

В разработке развитие музыкального материала построено на коротком мотиве, также пронизанном лейтритмом. Здесь происходит слияние жанрового и героического симфонизма, присутствует не только стремительное полифоническое движение, а также и гомофонные моменты.Динамическое развитие в разработке подводит к репризе, которая в отличие от экспозиции характеризуется более активным характером и к своему пасторальному обличию не возвращается.

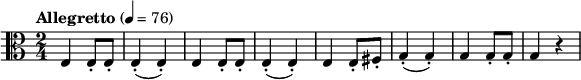

Вторая часть – Allegretto, являющаяся прекраснейшим образцом бетховенского творчества, заключена в сложную трёхчастную форму. В первой и третьей части, написанных в ля миноре, композитор использовал две темы, которые подверг искусному контрапунктическому варьированию. Первая тема по своему характеру напоминает траурный марш, однако он наполнен не бессильной скорбью, а мужественной печалью. Его остинатная пульсация составляет основу ритма всего «Allegretto». Начинающаяся с прозрачного пианиссимо виолончелей и контрабасов тема постепенно разрастается и, охватывая всё больше оркестровых регистров, подходит к насыщенному тутти. Вторая тема, создающая светлый контраст и имеющая нежную, обаятельную мелодическую линию, впервые возникает в средних голосах как подголосок. После первого проведения, порученного виолончелям и альтам, она, активно развиваясь, впоследствии, как и первая тема занимает доминирующие позиции. Следующий за первым разделом, мажорный средний эпизод, вносит в музыку Allegretto мечтательность и просветление. Далее в динамической репризе вновь возвращается трагический настрой. Здесь интенсивное фугированное развитие первой темы подводит к кульминации, в которой ярко выражен бетховенский драматизм.

Третья часть. Presto. Представляет собой фееричное скерцо, написанное в двойной трёхчастной форме, которую можно представить схемой: А В А В А. Радостная музыка с лёгкой и игривой мелодической линией, мощным стремительным потоком и сочным звучанием всего оркестра воплощает буйное веселье. Композитор, используя красочные гармонии, эффектное тональное варьирование и масштабное симфоническое развитие, создаёт настроение яркого праздника. Следующее затем трио резко контрастирует с первой частью. Его простая, но солнечная тема, в которой Бетховен использовал напев австрийской народной песни, основана на мелодическом мотиве, напоминающий вздох. Впоследствии в репризе в процессе развития эта тема дорастает до величественного гимна.

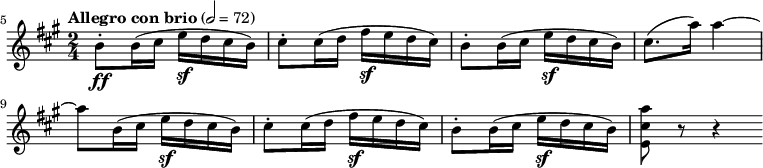

Четвёртая часть. Allegro con brio. Музыка финала, пропитанная народными танцевальными мотивами, рисует пьянящий ликующий праздник. Здесь каждый такт пропитан радостным весельем. Темпераментность острых ритмов, подчёркнутых синкопами, отображает безудержную пляску, однако в результате развития в тематическом материале всё чаще звучат призывные героические интонации, которые получают яркое выражение в коде.

Сегодня вызывает большое удивление, что такое яркое и бесценное творение, как Седьмая симфония Бетховена, изначально так негативно было встречено современниками — коллегами композитора. Тем не менее время всё расставило по своим местам, и в нынешний век выдающееся сочинение гениального маэстро заняло достойное место в сокровищнице мировых музыкальных произведений.

Понравилась страница? Поделитесь с друзьями:

Людвиг ван Бетховен Симфония №7

| Symphony in A major | |

|---|---|

| No. 7 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

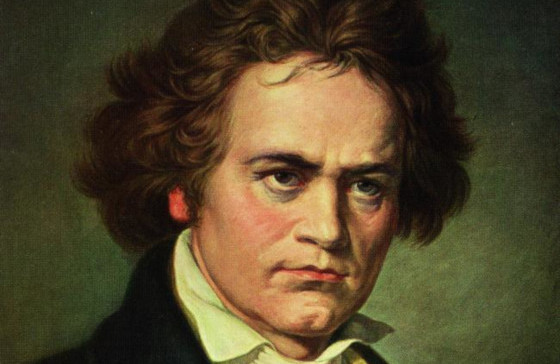

Portrait of Beethoven by Louis Letronne in 1814 | |

| Key | A major |

| Opus | 92 |

| Composed | 1811–1812: Teplitz |

| Dedication | Count Moritz von Fries |

| Performed | 8 December 1813: Vienna |

| Movements | Four |

The Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92, is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1811 and 1812, while improving his health in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. The work is dedicated to Count Moritz von Fries.

At its premiere at the University in Vienna on 8 December 1813, Beethoven remarked that it was one of his best works. The second movement, «Allegretto», was so popular that audiences demanded an encore.[1] The «Allegretto» is frequently performed separately to this day.

History[edit]

When Beethoven began composing the 7th symphony, Napoleon was planning his campaign against Russia. After the 3rd Symphony, and possibly the 5th as well, the 7th Symphony seems to be another of Beethoven’s musical confrontations with Napoleon, this time in the context of the European wars of liberation from years of Napoleonic domination.[2]

Beethoven’s life at this time was marked by a worsening hearing loss, which made «conversation notebooks» necessary from 1819 on, with the help of which Beethoven communicated in writing.[3]

Premiere[edit]

The work was premiered with Beethoven himself conducting in Vienna on 8 December 1813 at a charity concert for soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau. In Beethoven’s address to the participants, the motives are not openly named: «We are moved by nothing but pure patriotism and the joyful sacrifice of our powers for those who have sacrificed so much for us.»[4]

The program also included the patriotic work Wellington’s Victory, exalting the victory of the British over Napoleon’s France. The orchestra was led by Beethoven’s friend Ignaz Schuppanzigh and included some of the finest musicians of the day: violinist Louis Spohr,[5] composers Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Giacomo Meyerbeer and Antonio Salieri.[6] The Italian guitar virtuoso Mauro Giuliani played cello at the premiere.[7]

The piece was very well received, such that the audience demanded the Allegretto movement be encored immediately.[5] Spohr made particular mention of Beethoven’s enthusiastic gestures on the podium («as a sforzando occurred, he tore his arms with a great vehemence asunder … at the entrance of a forte he jumped in the air»), and «the friends of Beethoven made arrangements for a repetition of the concert» by which «Beethoven was extricated from his pecuniary difficulties».[8]

Editions[edit]

The first edition of the score, parts and piano reduction was published in November 1816 by Steiner & Comp.[citation needed]

A facsimile of Beethoven’s manuscript was published in 2017 by Laaber Verlag.[9]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons, 2 horns in A (E and D in the inner movements), 2 trumpets in D, timpani, and strings.[citation needed]

Form[edit]

There are four movements:

- Poco sostenuto – Vivace (A major)

- Allegretto (A minor)

- Presto – Assai meno presto (trio) (F major, Trio in D major)

- Allegro con brio (A major)

A typical performance lasts approximately 40 minutes.

The work as a whole is known for its use of rhythmic devices suggestive of a dance, such as dotted rhythm and repeated rhythmic figures. It is also tonally subtle, making use of the tensions between the key centres of A, C and F. For instance, the first movement is in A major but has repeated episodes in C major and F major. In addition, the second movement is in A minor with episodes in A major, and the third movement, a scherzo, is in F major.[10]

I. Poco sostenuto – Vivace[edit]

The first movement starts with a long, expanded introduction marked Poco sostenuto (metronome mark: ![]() = 69) that is noted for its long ascending scales and a cascading series of applied dominants that facilitates modulations to C major and F major. From the last episode in F major, the movement transitions to Vivace through a series of no fewer than sixty-one repetitions of the note E.

= 69) that is noted for its long ascending scales and a cascading series of applied dominants that facilitates modulations to C major and F major. From the last episode in F major, the movement transitions to Vivace through a series of no fewer than sixty-one repetitions of the note E.

The Vivace (![]() . = 104) is in sonata form, and is dominated by lively dance-like dotted rhythms, sudden dynamic changes, and abrupt modulations. The first theme of the Vivace is shown below.

. = 104) is in sonata form, and is dominated by lively dance-like dotted rhythms, sudden dynamic changes, and abrupt modulations. The first theme of the Vivace is shown below.

The development section opens in C major and contains extensive episodes in F major. The movement finishes with a long coda, which starts similarly as the development section. The coda contains a famous twenty-bar passage consisting of a two-bar motif repeated ten times to the background of a grinding four octave deep pedal point of an E.

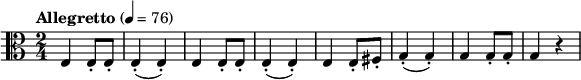

II. Allegretto[edit]

The second movement in A minor has a tempo marking of allegretto («a little lively»), making it slow only in comparison to the other three movements. This movement was encored at the premiere and has remained popular since. Its reliance on the string section makes it a good example of Beethoven’s advances in orchestral writing for strings, building on the experimental innovations of Haydn.[11]

The movement is structured in ternary form. It begins with the main melody played by the violas and cellos, an ostinato (repeated rhythmic figure, or ground bass, or passacaglia of a quarter note, two eighth notes and two quarter notes).

This melody is then played by the second violins while the violas and cellos play a second melody, described by George Grove as, «like a string of beauties hand-in-hand, each afraid to lose her hold on her neighbours».[12] The first violins then take the first melody while the second violins take the second. This progression culminates with the wind section playing the first melody while the first violin plays the second.

After this, the music changes from A minor to A major as the clarinets take a calmer melody to the background of light triplets played by the violins. This section ends thirty-seven bars later with a quick descent of the strings on an A minor scale, and the first melody is resumed and elaborated upon in a strict fugato.

III. Presto – Assai meno presto[edit]

The third movement is a scherzo in F major and trio in D major. Here, the trio (based on an Austrian pilgrims’ hymn[13]) is played twice rather than once. This expansion of the usual A–B–A structure of ternary form into A–B–A–B–A was quite common in other works of Beethoven of this period, such as his Fourth Symphony, Pastoral Symphony, 8th Symphony, and String Quartet Op. 59 No. 2.

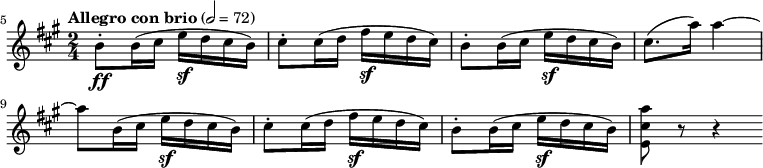

IV. Allegro con brio[edit]

The last movement is in sonata form. According to music historian Glenn Stanley, Beethoven «exploited the possibility that a string section can realize both angularity and rhythmic contrast if used as an obbligato-like background»,[11] particularly in the coda, which contains an example, rare in Beethoven’s music, of the dynamic marking fff.

In his book Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies, Sir George Grove wrote, «The force that reigns throughout this movement is literally prodigious, and reminds one of Carlyle’s hero Ram Dass, who has ‘fire enough in his belly to burn up the entire world.'» Donald Tovey, writing in his Essays in Musical Analysis, commented on this movement’s «Bacchic fury» and many other writers have commented on its whirling dance-energy. The main theme is a precise duple time variant of the instrumental ritornello in Beethoven’s own arrangement of the Irish folk-song «Save me from the grave and wise», No. 8 of his Twelve Irish Folk Songs, WoO 154.

Reception[edit]

Critics and listeners have often felt stirred or inspired by the Seventh Symphony. For instance, one program-note author writes:

… the final movement zips along at an irrepressible pace that threatens to sweep the entire orchestra off its feet and around the theater, caught up in the sheer joy of performing one of the most perfect symphonies ever written.[14]

Composer and music author Antony Hopkins says of the symphony:

The Seventh Symphony perhaps more than any of the others gives us a feeling of true spontaneity; the notes seem to fly off the page as we are borne along on a floodtide of inspired invention. Beethoven himself spoke of it fondly as «one of my best works». Who are we to dispute his judgment?[15]

Another admirer, composer Richard Wagner, referring to the lively rhythms which permeate the work, called it the «apotheosis of the dance».[12]

On the other hand, admiration for the work has not been universal. Friedrich Wieck, who was present during rehearsals, said that the consensus, among musicians and laymen alike, was that Beethoven must have composed the symphony in a drunken state;[16] and the conductor Thomas Beecham commented on the third movement: «What can you do with it? It’s like a lot of yaks jumping about.»[17]

The oft-repeated claim that Carl Maria von Weber considered the chromatic bass line in the coda of the first movement evidence that Beethoven was «ripe for the madhouse» seems to have been the invention of Beethoven’s first biographer, Anton Schindler. His possessive adulation of Beethoven is well-known, and he was criticised by his contemporaries for his obsessive attacks on Weber. According to John Warrack, Weber’s biographer, Schindler was characteristically evasive when defending Beethoven, and there is «no shred of concrete evidence» that Weber ever made the remark.[18]

In popular culture[edit]

- The 1934 horror film The Black Cat features the second movement prominently.[19]

- The 1974 science fiction film Zardoz (1974), directed by John Boorman. An excerpt from the Second Movement is played over the closing montage and the end credits.[20]

- The first episode of Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980) features the first movement to «underscore the vastness and diversity of Earth with its ‘resplendent spaciousness'».[19]

- The 1995 drama film Mr. Holland’s Opus uses the second movement to underscore the high school music teacher Mr. Holland recounting the tragedy of Beethoven’s hearing loss, with Holland’s son being deaf and unable to share his father’s passion for music.[19]

- The 2006 film The Fall uses the second movement at several points in the film.[21]

- The 2006 live-action adaption of Nodame Cantabile uses the first movement as the opening theme. The 2007 anime adaptation uses it as the ending theme.[22]

- The 2007 comedy-drama film The Darjeeling Limited uses the fourth movement.[19]

- The 2009 science fiction film Knowing uses the second movement during the climactic scene, a mass exodus from apocalyptic Boston.[23]

- In the 2010 historical drama film The King’s Speech, the second movement is used during King George’s climactic speech at Buckingham Palace after the commencement of the country’s involvement in World War II. The slow build up of the movement «accents his struggle and his perseverance».[19][23]

- In the 2016 superhero film X-Men: Apocalypse the second movement is played during the launch of all the world’s nuclear weapons.[24][25]

References[edit]

- ^ «Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92» at NPR (13 June 2006)

- ^ Goldschmidt 1975, pp. 29–33, 39–43, 49–55.

- ^ Ulm, Renate (1994). Die 9 Sinfonien Beethovens. Kassel: Bärenreiter. p. 214. ISBN 978-3-7618-1241-9. OCLC 363133953.

- ^ Goldschmidt 1975, p. 49 Original in German: «Uns alle erfüllt nichts als das reine Gefühl der Vaterlandsliebe und des freudigen Opfers unserer Kräfte für diejenigen, die uns so viel geopfert haben.»

- ^ a b Steinberg, Michael. The Symphony: A Listeners Guide. pp. 38–43. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ Swafford, Jan (2014). Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 615ff. ISBN 978-0-618-05474-9.

- ^ Annala, Hannu; Matlik, Heiki (2010). Handbook of Guitar and Lute Composers. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-0786658442. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Spohr, Louis (1865). Autobiography. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green. pp. 186–187.

- ^ Beethoven, Ludwig van (2017). Sinfonie Nr. 7, A-Dur, op. 92. Laaber, Germany: Laaber-Verlag. ISBN 9783946798132. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ «Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92 (1812)». University of Rochester. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ a b Stanley, Glenn (11 May 2000). The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. Cambridge University Press. pp. 181ff. ISBN 978-0-521-58934-5.

- ^ a b Grove, Sir George (1962). Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies (3rd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 252. OCLC 705665.

- ^ Grove 1962, pp. 228–271.

- ^ Geoff Kuenning. «Beethoven: Symphony No. 7». (personal web page).

- ^ Hopkins 1981, p. 219.

- ^ Meltzer, Ken (17 February 2011). «Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Program Notes» (PDF).

- ^ Bicknell, David (EMI executive). «Sir Thomas Beecham». Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- ^ Warrack, John Hamilton (1976). Carl Maria von Weber (reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press Archive. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0521291216.

- ^ a b c d e Hope, Sarah (1 June 2014). «Beethoven’s 7th symphony in movies and TV». The Post and Courier. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Music and Medievalism. Eds. Stephen C. Meyer and Kirsten Yri. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. p. 230.

- ^ Ulloa, Alexander; Landekic, Lola. «The Fall (2006)». Art of the Title.

- ^ Wyman, Walt; Fujie, Kazuhisa; Carr, Sian; Sasaki, Naohiko (2007). Nodame Cantabile: The Essential Guide. Tokyo: Cocoro Books. ISBN 978-1-932897-33-3. OCLC 227272801.

- ^ a b Helligar, Jeremy (25 January 2011). «How Beethoven Saved the King’s Speech and Almost Ruined the Movie». The Faster Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015.

- ^ «X-Men: Apocalypse Soundtrack». tunefind. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ «A List of Beethoven’s Music That Has Appeared in the Movies». liveabout. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Goldschmidt, Harry (1975). Beethoven. Werkeinführungen (in German). Leipzig: Reclam.

- Hopkins, Antony (1981). The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Seattle: Heinemann, University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95823-1. OCLC 6981522.

External links[edit]

| External video |

|---|

| Performances of the Seventh Symphony |

Media related to Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons- Symphony No. 7: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Full Score of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony

- «Notes on Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony» by Christopher H. Gibbs, program note for a Philadelphia Orchestra performance, via NPR, 13 June 2006

- «Aperçu of Apotheosis», Program notes by Ron Drummond, Northwest Sinfonietta, October 2003

- Program notes by Christine Lee Gengaro for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, November 2010

- Peter Gutmann (2013). «Classical Notes: Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92».

| Symphony in A major | |

|---|---|

| No. 7 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Portrait of Beethoven by Louis Letronne in 1814 | |

| Key | A major |

| Opus | 92 |

| Composed | 1811–1812: Teplitz |

| Dedication | Count Moritz von Fries |

| Performed | 8 December 1813: Vienna |

| Movements | Four |

The Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92, is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1811 and 1812, while improving his health in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. The work is dedicated to Count Moritz von Fries.

At its premiere at the University in Vienna on 8 December 1813, Beethoven remarked that it was one of his best works. The second movement, «Allegretto», was so popular that audiences demanded an encore.[1] The «Allegretto» is frequently performed separately to this day.

History[edit]

When Beethoven began composing the 7th symphony, Napoleon was planning his campaign against Russia. After the 3rd Symphony, and possibly the 5th as well, the 7th Symphony seems to be another of Beethoven’s musical confrontations with Napoleon, this time in the context of the European wars of liberation from years of Napoleonic domination.[2]

Beethoven’s life at this time was marked by a worsening hearing loss, which made «conversation notebooks» necessary from 1819 on, with the help of which Beethoven communicated in writing.[3]

Premiere[edit]

The work was premiered with Beethoven himself conducting in Vienna on 8 December 1813 at a charity concert for soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau. In Beethoven’s address to the participants, the motives are not openly named: «We are moved by nothing but pure patriotism and the joyful sacrifice of our powers for those who have sacrificed so much for us.»[4]

The program also included the patriotic work Wellington’s Victory, exalting the victory of the British over Napoleon’s France. The orchestra was led by Beethoven’s friend Ignaz Schuppanzigh and included some of the finest musicians of the day: violinist Louis Spohr,[5] composers Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Giacomo Meyerbeer and Antonio Salieri.[6] The Italian guitar virtuoso Mauro Giuliani played cello at the premiere.[7]

The piece was very well received, such that the audience demanded the Allegretto movement be encored immediately.[5] Spohr made particular mention of Beethoven’s enthusiastic gestures on the podium («as a sforzando occurred, he tore his arms with a great vehemence asunder … at the entrance of a forte he jumped in the air»), and «the friends of Beethoven made arrangements for a repetition of the concert» by which «Beethoven was extricated from his pecuniary difficulties».[8]

Editions[edit]

The first edition of the score, parts and piano reduction was published in November 1816 by Steiner & Comp.[citation needed]

A facsimile of Beethoven’s manuscript was published in 2017 by Laaber Verlag.[9]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons, 2 horns in A (E and D in the inner movements), 2 trumpets in D, timpani, and strings.[citation needed]

Form[edit]

There are four movements:

- Poco sostenuto – Vivace (A major)

- Allegretto (A minor)

- Presto – Assai meno presto (trio) (F major, Trio in D major)

- Allegro con brio (A major)

A typical performance lasts approximately 40 minutes.

The work as a whole is known for its use of rhythmic devices suggestive of a dance, such as dotted rhythm and repeated rhythmic figures. It is also tonally subtle, making use of the tensions between the key centres of A, C and F. For instance, the first movement is in A major but has repeated episodes in C major and F major. In addition, the second movement is in A minor with episodes in A major, and the third movement, a scherzo, is in F major.[10]

I. Poco sostenuto – Vivace[edit]

The first movement starts with a long, expanded introduction marked Poco sostenuto (metronome mark: ![]() = 69) that is noted for its long ascending scales and a cascading series of applied dominants that facilitates modulations to C major and F major. From the last episode in F major, the movement transitions to Vivace through a series of no fewer than sixty-one repetitions of the note E.

= 69) that is noted for its long ascending scales and a cascading series of applied dominants that facilitates modulations to C major and F major. From the last episode in F major, the movement transitions to Vivace through a series of no fewer than sixty-one repetitions of the note E.

The Vivace (![]() . = 104) is in sonata form, and is dominated by lively dance-like dotted rhythms, sudden dynamic changes, and abrupt modulations. The first theme of the Vivace is shown below.

. = 104) is in sonata form, and is dominated by lively dance-like dotted rhythms, sudden dynamic changes, and abrupt modulations. The first theme of the Vivace is shown below.

The development section opens in C major and contains extensive episodes in F major. The movement finishes with a long coda, which starts similarly as the development section. The coda contains a famous twenty-bar passage consisting of a two-bar motif repeated ten times to the background of a grinding four octave deep pedal point of an E.

II. Allegretto[edit]

The second movement in A minor has a tempo marking of allegretto («a little lively»), making it slow only in comparison to the other three movements. This movement was encored at the premiere and has remained popular since. Its reliance on the string section makes it a good example of Beethoven’s advances in orchestral writing for strings, building on the experimental innovations of Haydn.[11]

The movement is structured in ternary form. It begins with the main melody played by the violas and cellos, an ostinato (repeated rhythmic figure, or ground bass, or passacaglia of a quarter note, two eighth notes and two quarter notes).

This melody is then played by the second violins while the violas and cellos play a second melody, described by George Grove as, «like a string of beauties hand-in-hand, each afraid to lose her hold on her neighbours».[12] The first violins then take the first melody while the second violins take the second. This progression culminates with the wind section playing the first melody while the first violin plays the second.

After this, the music changes from A minor to A major as the clarinets take a calmer melody to the background of light triplets played by the violins. This section ends thirty-seven bars later with a quick descent of the strings on an A minor scale, and the first melody is resumed and elaborated upon in a strict fugato.

III. Presto – Assai meno presto[edit]

The third movement is a scherzo in F major and trio in D major. Here, the trio (based on an Austrian pilgrims’ hymn[13]) is played twice rather than once. This expansion of the usual A–B–A structure of ternary form into A–B–A–B–A was quite common in other works of Beethoven of this period, such as his Fourth Symphony, Pastoral Symphony, 8th Symphony, and String Quartet Op. 59 No. 2.

IV. Allegro con brio[edit]

The last movement is in sonata form. According to music historian Glenn Stanley, Beethoven «exploited the possibility that a string section can realize both angularity and rhythmic contrast if used as an obbligato-like background»,[11] particularly in the coda, which contains an example, rare in Beethoven’s music, of the dynamic marking fff.

In his book Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies, Sir George Grove wrote, «The force that reigns throughout this movement is literally prodigious, and reminds one of Carlyle’s hero Ram Dass, who has ‘fire enough in his belly to burn up the entire world.'» Donald Tovey, writing in his Essays in Musical Analysis, commented on this movement’s «Bacchic fury» and many other writers have commented on its whirling dance-energy. The main theme is a precise duple time variant of the instrumental ritornello in Beethoven’s own arrangement of the Irish folk-song «Save me from the grave and wise», No. 8 of his Twelve Irish Folk Songs, WoO 154.

Reception[edit]

Critics and listeners have often felt stirred or inspired by the Seventh Symphony. For instance, one program-note author writes:

… the final movement zips along at an irrepressible pace that threatens to sweep the entire orchestra off its feet and around the theater, caught up in the sheer joy of performing one of the most perfect symphonies ever written.[14]

Composer and music author Antony Hopkins says of the symphony:

The Seventh Symphony perhaps more than any of the others gives us a feeling of true spontaneity; the notes seem to fly off the page as we are borne along on a floodtide of inspired invention. Beethoven himself spoke of it fondly as «one of my best works». Who are we to dispute his judgment?[15]

Another admirer, composer Richard Wagner, referring to the lively rhythms which permeate the work, called it the «apotheosis of the dance».[12]

On the other hand, admiration for the work has not been universal. Friedrich Wieck, who was present during rehearsals, said that the consensus, among musicians and laymen alike, was that Beethoven must have composed the symphony in a drunken state;[16] and the conductor Thomas Beecham commented on the third movement: «What can you do with it? It’s like a lot of yaks jumping about.»[17]

The oft-repeated claim that Carl Maria von Weber considered the chromatic bass line in the coda of the first movement evidence that Beethoven was «ripe for the madhouse» seems to have been the invention of Beethoven’s first biographer, Anton Schindler. His possessive adulation of Beethoven is well-known, and he was criticised by his contemporaries for his obsessive attacks on Weber. According to John Warrack, Weber’s biographer, Schindler was characteristically evasive when defending Beethoven, and there is «no shred of concrete evidence» that Weber ever made the remark.[18]

In popular culture[edit]

- The 1934 horror film The Black Cat features the second movement prominently.[19]

- The 1974 science fiction film Zardoz (1974), directed by John Boorman. An excerpt from the Second Movement is played over the closing montage and the end credits.[20]

- The first episode of Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980) features the first movement to «underscore the vastness and diversity of Earth with its ‘resplendent spaciousness'».[19]

- The 1995 drama film Mr. Holland’s Opus uses the second movement to underscore the high school music teacher Mr. Holland recounting the tragedy of Beethoven’s hearing loss, with Holland’s son being deaf and unable to share his father’s passion for music.[19]

- The 2006 film The Fall uses the second movement at several points in the film.[21]

- The 2006 live-action adaption of Nodame Cantabile uses the first movement as the opening theme. The 2007 anime adaptation uses it as the ending theme.[22]

- The 2007 comedy-drama film The Darjeeling Limited uses the fourth movement.[19]

- The 2009 science fiction film Knowing uses the second movement during the climactic scene, a mass exodus from apocalyptic Boston.[23]

- In the 2010 historical drama film The King’s Speech, the second movement is used during King George’s climactic speech at Buckingham Palace after the commencement of the country’s involvement in World War II. The slow build up of the movement «accents his struggle and his perseverance».[19][23]

- In the 2016 superhero film X-Men: Apocalypse the second movement is played during the launch of all the world’s nuclear weapons.[24][25]

References[edit]

- ^ «Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92» at NPR (13 June 2006)

- ^ Goldschmidt 1975, pp. 29–33, 39–43, 49–55.

- ^ Ulm, Renate (1994). Die 9 Sinfonien Beethovens. Kassel: Bärenreiter. p. 214. ISBN 978-3-7618-1241-9. OCLC 363133953.

- ^ Goldschmidt 1975, p. 49 Original in German: «Uns alle erfüllt nichts als das reine Gefühl der Vaterlandsliebe und des freudigen Opfers unserer Kräfte für diejenigen, die uns so viel geopfert haben.»

- ^ a b Steinberg, Michael. The Symphony: A Listeners Guide. pp. 38–43. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ Swafford, Jan (2014). Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 615ff. ISBN 978-0-618-05474-9.

- ^ Annala, Hannu; Matlik, Heiki (2010). Handbook of Guitar and Lute Composers. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-0786658442. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Spohr, Louis (1865). Autobiography. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green. pp. 186–187.

- ^ Beethoven, Ludwig van (2017). Sinfonie Nr. 7, A-Dur, op. 92. Laaber, Germany: Laaber-Verlag. ISBN 9783946798132. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ «Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92 (1812)». University of Rochester. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ a b Stanley, Glenn (11 May 2000). The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. Cambridge University Press. pp. 181ff. ISBN 978-0-521-58934-5.

- ^ a b Grove, Sir George (1962). Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies (3rd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 252. OCLC 705665.

- ^ Grove 1962, pp. 228–271.

- ^ Geoff Kuenning. «Beethoven: Symphony No. 7». (personal web page).

- ^ Hopkins 1981, p. 219.

- ^ Meltzer, Ken (17 February 2011). «Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Program Notes» (PDF).

- ^ Bicknell, David (EMI executive). «Sir Thomas Beecham». Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- ^ Warrack, John Hamilton (1976). Carl Maria von Weber (reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press Archive. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0521291216.

- ^ a b c d e Hope, Sarah (1 June 2014). «Beethoven’s 7th symphony in movies and TV». The Post and Courier. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Music and Medievalism. Eds. Stephen C. Meyer and Kirsten Yri. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. p. 230.

- ^ Ulloa, Alexander; Landekic, Lola. «The Fall (2006)». Art of the Title.

- ^ Wyman, Walt; Fujie, Kazuhisa; Carr, Sian; Sasaki, Naohiko (2007). Nodame Cantabile: The Essential Guide. Tokyo: Cocoro Books. ISBN 978-1-932897-33-3. OCLC 227272801.

- ^ a b Helligar, Jeremy (25 January 2011). «How Beethoven Saved the King’s Speech and Almost Ruined the Movie». The Faster Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015.

- ^ «X-Men: Apocalypse Soundtrack». tunefind. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ «A List of Beethoven’s Music That Has Appeared in the Movies». liveabout. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Goldschmidt, Harry (1975). Beethoven. Werkeinführungen (in German). Leipzig: Reclam.

- Hopkins, Antony (1981). The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Seattle: Heinemann, University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95823-1. OCLC 6981522.

External links[edit]

| External video |

|---|

| Performances of the Seventh Symphony |

Media related to Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven) at Wikimedia Commons- Symphony No. 7: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Full Score of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony

- «Notes on Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony» by Christopher H. Gibbs, program note for a Philadelphia Orchestra performance, via NPR, 13 June 2006

- «Aperçu of Apotheosis», Program notes by Ron Drummond, Northwest Sinfonietta, October 2003

- Program notes by Christine Lee Gengaro for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, November 2010

- Peter Gutmann (2013). «Classical Notes: Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92».

Л. Бетховен — 7-я симфония, 2-я часть (фрагмент)

слушатьскачать03:15

Д.Смирнов — Саундтрек к фильму «Смерть Таирова» (обработка 2 части 7-й симфонии Бетховена)

слушатьскачать01:00

Неизвестен — Бетховен 7 симфония 2 часть с вокалом

слушатьскачать03:37

Бетховен(дирижер — В. Фуртвенглер) — Симфония №7 — 2-я часть

слушатьскачать09:48

Людвиг ван Бетховен — Симфония № 7. 2 часть

слушатьскачать10:02

ВФО и Кристиан Тилеманн — Бетховен — Симфония №7 часть 2

слушатьскачать09:10

Арт-группа «Хорус-квартет» — Бетховен, симфония №7 часть 2(Героям Новороссии посвящается)

слушатьскачать04:11

Бетховен — 7 симфония, 2 часть аллегретто

слушатьскачать08:43

Ludwig van Beethoven — — Симфония №7,ля мажор, часть 2 Аллегретто

слушатьскачать08:43

Бернард Хайтинк и Лондонский симфонический оркестр — Бетховен. Симфония № 7. Часть 2

слушатьскачать07:40

Бетховен — Симфония 7 , 2 часть

слушатьскачать09:40

Людвиг ван Бетховен — Симфония №7. Часть 2.

слушатьскачать09:30

Бетховен — 7 симфония 2 часть (скрипка соло)

слушатьскачать01:50

Бетховен — симфония №7, часть 2 Allegretto

слушатьскачать09:26

Ludwig van Beethoven — симфония № 7 . 2 часть Allegretto

слушатьскачать03:06

Бетховен (Знаменье) — 7 симфония, часть 2, фрагмент

слушатьскачать03:10

Бетховен — Симфония 7 2 часть

слушатьскачать01:29

Wilhelm Furtwängler и Берлинский Филармонический О — БЕТХОВЕН. Симфония № 7. Часть 2. Allegretto (1943)

слушатьскачать09:41

Бетховен — 7. Симфония №9 ре минор 2 часть

слушатьскачать11:28

В.Фуртвенглер — Л.В.Бетховен 7-я симфония 2-я часть(Allegretto).

слушатьскачать09:40

Людвиг ван Бетховен — Симфония № 7 A dur 2 часть Allegretto

слушатьскачать09:10

Бетховен — 7 симфония

слушатьскачать09:26

Людвиг ван Бетховен, 7-симфония («Irreversibl — «Финал»

слушатьскачать03:31

Людвиг ван Бетховен — Симфония №7 A-dur. Часть 2

слушатьскачать08:43

Берлинский филармонический оркестр. Вильгельм Фурт — Бетховен — Симфония №7. Часть 2. Allegretto

слушатьскачать09:40

Бетховен — симфония №7, 2 часть — Allegretto.

слушатьскачать09:46

неизвестен — Бетховен Симфония №7 2 часть

слушатьскачать03:15