Порядковый номер химического элемента

- Порядковый номер химического элемента

-

Заря́довое число́ атомного ядра (синонимы: атомный номер, атомное число, порядковый номер химического элемента) — количество протонов в атомном ядре. Зарядовое число равно заряду ядра в единицах элементарного заряда и одновременно равно порядковому номеру соответствующего ядру химического элемента в таблице Менделеева.

Термин «атомный» или «порядковый» номер обычно используется в атомной физике и химии, тогда как эквивалентный термин «зарядовое число» — в физике ядра. В неионизированном атоме количество электронов в электронных оболочках совпадает с зарядовым числом.

Зарядовое число обычно обозначается буквой Z. Ядра с одинаковым зарядовым числом, но различным массовым числом A (которое равно сумме числа протонов Z и числа нейтронов N) являются различными изотопами одного и того же химического элемента, поскольку именно заряд ядра определяет структуру электронной оболочки атома и, следовательно, его химические свойства.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Смотреть что такое «Порядковый номер химического элемента» в других словарях:

-

ПОРЯДКОВЫЙ НОМЕР — элемента, то же, что (см. АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР). Физический энциклопедический словарь. М.: Советская энциклопедия. Главный редактор А. М. Прохоров. 1983. ПОРЯДКОВЫЙ НОМЕР … Физическая энциклопедия

-

ПОРЯДКОВЫЙ НОМЕР — химического элемента то же, что атомный номер … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Порядковый номер элемента — Зарядовое число атомного ядра (синонимы: атомный номер, атомное число, порядковый номер химического элемента) количество протонов в атомном ядре. Зарядовое число равно заряду ядра в единицах элементарного заряда и одновременно равно порядковому… … Википедия

-

порядковый номер — химического элемента, то же, что атомный номер. * * * ПОРЯДКОВЫЙ НОМЕР ПОРЯДКОВЫЙ НОМЕР химического элемента, то же, что атомный номер (см. АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР) … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Атомный номер — порядковый номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов (См. Периодическая система элементов) Д. И. Менделеева. А. н. равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, которое, в свою очередь, равно числу электронов в электронной… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР, порядковый номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома … Современная энциклопедия

-

Атомный номер — АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР, порядковый номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома. … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

атомный номер — порядковый номер, Z, номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре и определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома. * * * АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР (порядковый номер), Z, номер… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — (порядковый номер) Z, номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре и определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Химический элемент — Химический элемент совокупность атомов с одинаковым зарядом ядра и числом протонов, совпадающим с порядковым (атомным) номером в таблице Менделеева[1]. Каждый химический элемент имеет свои название и символ, которые приводятся в… … Википедия

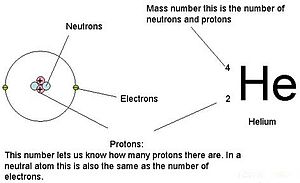

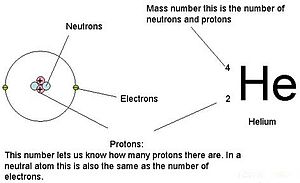

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

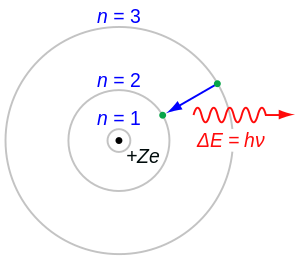

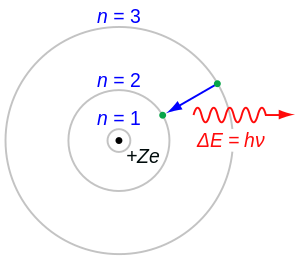

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

ГДЗ Химия 8 класc Габриелян О.С. , Остроумов И.Г., Сладков С.А. 2019 §32 ПЕРИОДИЧЕСКАЯ СИСТЕМА ХИМИЧЕСКИХ ЭЛЕМЕНТОВ Д.И.МЕНДЕЛЕЕВА

Красным цветом даются ответы, а фиолетовым ― объяснения.

Задание 1

Раскройте физический смысл порядкового номера химического элемента, номера периода, номера группы.

Порядковый номер химического элемента соответствует положительному заряду атомного ядра, т. е. числу содержащихся в нём протонов. Так как атом электронейтрален, то очевидно, что порядковый номер химического элемента соответствует также числу электронов, образующих электронную оболочку атома.

Номер периода, в котором расположен химический элемент, соответствует числу энергетических уровней (электронных слоёв) в атоме.

Номер группы соответствует числу электронов на внешнем энергетическом уровне атомов элементов А-групп.То есть, данная константа очень важна, потому что выражает величину заряда ядра.

Задание 2

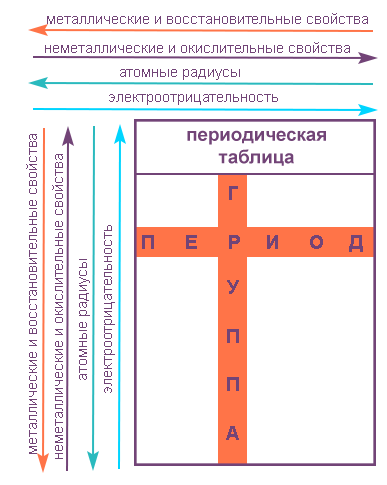

Как изменяются металлические и неметаллические свойства химических элементов:

а) в периодах;

В периодах с ростом порядкового номера химического элемента (слева направо) ослабевают металлические свойства и усиливаются неметаллические.

б) в группах?

В подгруппах с ростом порядкового номера химического элемента (сверху вниз) ослабевают неметаллические свойства и усиливаются металлические.

Задание 3

Охарактеризуйте химические элементы литий, бериллий и бор по плану:

| ПЛАН | литий | бериллий | бор |

| порядковый номер; | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| положение в Периодической системе (номер периода, номер группы, подгруппа); | 2 период, I группа, главная подгруппа | 2 период, II группа, главная подгруппа | 2 период, III группа, главная подгруппа |

| число протонов в ядре атома; | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| число энергетических уровней | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| общее число электронов; | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| число электронов на внешнем энергетическом уровне | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Задание 4

Определите количество электронов, которые нужно отдать или присоединить для получения завершённого внешнего энергетического уровня атомам следующих химических элементов:

кислород, Присоединить два (8-6=2)

натрий, Отдать один.

хлор, Присоединить один (8-7=1)

магний. Отдать два.

Чтобы определить число электронов, необходимое атому для завершения внешнего энергетического уровня, от восьми нужно отнять число электронов на внешнем энергетическом уровне, которое соответствует номеру группы, в которой находится химический элемент в Периодической системе Д.И.Менделеева.

Задание 5

Символы каких трёх химических элементов расположены в порядке увеличения радиусов их атомов:

а) P, Si; Al; Радиус в периоде (P, Si, Al) увеличивается.

б) С, N. О;

в) Са, Мg, Ве;

г) С, В, Аl? Радиус в периоде (С, В) и группе (В, Аl) увеличивается.

Радиус увеличивается вниз по подгруппе (за счет роста числа энергетических уровней) и справа налево по периоду (за счет уменьшения числа внешних электронов и силы их притяжения к ядру).

Задание 6

Выберите ряд чисел, которому соответствует распределение электронов по энергетическим уровням атома, металлические свойства которого выражены наиболее ярко:

а) 2, 8, 2; Магний Mg

б) 2, 8, 5; Фосфор P

в) 2, 8, 1; Натрий Na

г) 2, 8, 8, 1. Калий K

Наиболее сильно металлические свойства выражены в элемента с наименьшим числом внешних электронов и наибольшим числом энергетических уровней.

Задание 7

Дайте свою оценку строкам из стихотворения С. Щипачёва «Читая Менделеева»: Другого ничего в природе нет ни здесь, ни там, в космических глубинах: всё — от песчинок малых до планет — из элементов состоит единых.

С. Щипачёв поэтично изложил мысль о фундаментальном законе природе — периодическом законе, позволяющем объяснить и предусмотреть свойства химических элементов и образуемых ими соединений.

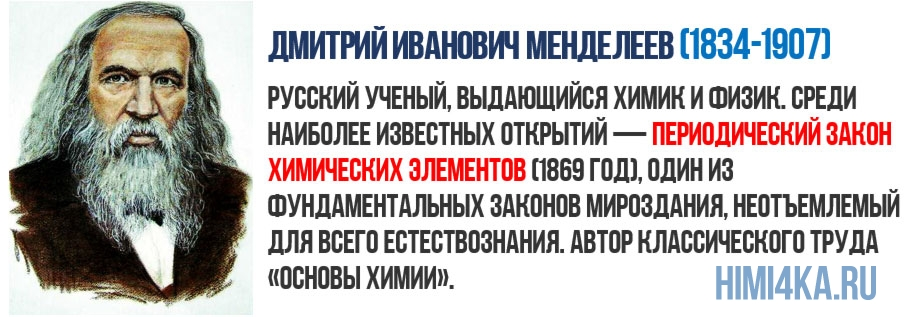

ПЕРИОДИЧЕСКАЯ ТАБЛИЦА МЕНДЕЛЕЕВА

Еще в школе, сидя на уроках химии, все мы помним таблицу на стене класса или химической лаборатории. Эта таблица содержала классификацию всех известных человечеству химических элементов, тех фундаментальных компонентов, из которых состоит Земля и вся Вселенная. Тогда мы и подумать не могли, что таблица Менделеева бесспорно является одним из величайших научных открытий, который является фундаментом нашего современного знания о химии.

На первый взгляд, ее идея выглядит обманчиво просто: организовать химические элементы в порядке возрастания веса их атомов. Причем в большинстве случаев оказывается, что химические и физические свойства каждого элемента сходны с предыдущим ему в таблице элементом. Эта закономерность проявляется для всех элементов, кроме нескольких самых первых, просто потому что они не имеют перед собой элементов, сходных с ними по атомному весу. Именно благодаря открытию такого свойства мы можем поместить линейную последовательность элементов в таблицу, очень напоминающую настенный календарь, и таким образом объединить огромное количество видов химических элементов в четкой и связной форме. Разумеется, сегодня мы пользуемся понятием атомного числа (количества протонов) для того, чтобы упорядочить систему элементов. Это помогло решить так называемую техническую проблему «пары перестановок», однако не привело к кардинальному изменению вида периодической таблицы.

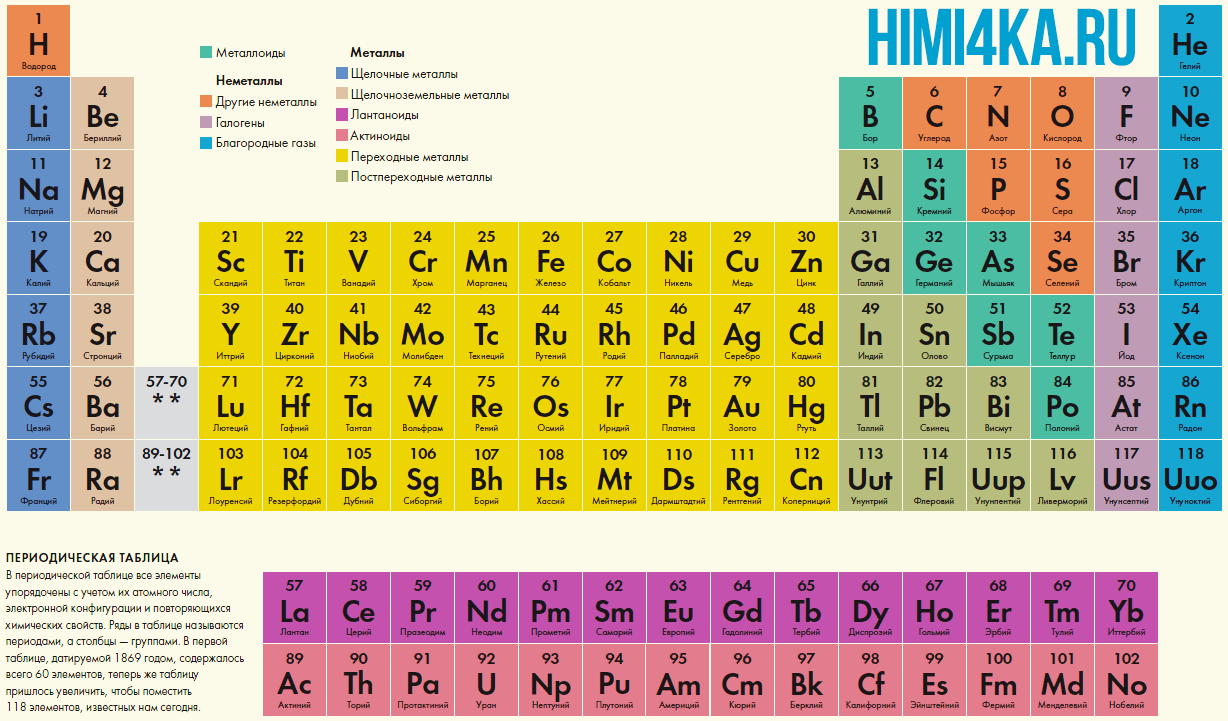

В периодической таблице Менделеева все элементы упорядочены с учетом их атомного числа, электронной конфигурации и повторяющихся химических свойств. Ряды в таблице называются периодами, а столбцы группами. В первой таблице, датируемой 1869 годом, содержалось всего 60 элементов, теперь же таблицу пришлось увеличить, чтобы поместить 118 элементов, известных нам сегодня.

Периодическая система Менделеева систематизирует не только элементы, но и самые разнообразные их свойства. Химику часто бывает достаточно иметь перед глазами Периодическую таблицу для того, чтобы правильно ответить на множество вопросов (не только экзаменационных, но и научных).

The YouTube ID of 1M7iKKVnPJE is invalid.

Периодический закон

Существуют две формулировки периодического закона химических элементов: классическая и современная.

Классическая, в изложении его первооткрывателя Д.И. Менделеева: свойства простых тел, а также формы и свойства соединений элементов находятся в периодической зависимости от величин атомных весов элементов.

Современная: свойства простых веществ, а также свойства и формы соединений элементов находятся в периодической зависимости от заряда ядра атомов элементов (порядкового номера).

Графическим изображением периодического закона является периодическая система элементов, которая представляет собой естественную классификацию химических элементов, основанную на закономерных изменениях свойств элементов от зарядов их атомов. Наиболее распространёнными изображениями периодической системы элементов Д.И. Менделеева являются короткая и длинная формы.

Группы и периоды Периодической системы

Группами называют вертикальные ряды в периодической системе. В группах элементы объединены по признаку высшей степени окисления в оксидах. Каждая группа состоит из главной и побочной подгрупп. Главные подгруппы включают в себя элементы малых периодов и одинаковые с ним по свойствам элементы больших периодов. Побочные подгруппы состоят только из элементов больших периодов. Химические свойства элементов главных и побочных подгрупп значительно различаются.

Периодом называют горизонтальный ряд элементов, расположенных в порядке возрастания порядковых (атомных) номеров. В периодической системе имеются семь периодов: первый, второй и третий периоды называют малыми, в них содержится соответственно 2, 8 и 8 элементов; остальные периоды называют большими: в четвёртом и пятом периодах расположены по 18 элементов, в шестом — 32, а в седьмом (пока незавершенном) — 31 элемент. Каждый период, кроме первого, начинается щелочным металлом, а заканчивается благородным газом.

Физический смысл порядкового номера химического элемента: число протонов в атомном ядре и число электронов, вращающихся вокруг атомного ядра, равны порядковому номеру элемента.

Свойства таблицы Менделеева

Напомним, что группами называют вертикальные ряды в периодической системе и химические свойства элементов главных и побочных подгрупп значительно различаются.

Свойства элементов в подгруппах закономерно изменяются сверху вниз:

- усиливаются металлические свойства и ослабевают неметаллические;

- возрастает атомный радиус;

- возрастает сила образованных элементом оснований и бескислородных кислот;

- электроотрицательность падает.

Все элементы, кроме гелия, неона и аргона, образуют кислородные соединения, существует всего восемь форм кислородных соединений. В периодической системе их часто изображают общими формулами, расположенными под каждой группой в порядке возрастания степени окисления элементов: R2O, RO, R2O3, RO2, R2O5, RO3, R2O7, RO4, где символом R обозначают элемент данной группы. Формулы высших оксидов относятся ко всем элементам группы, кроме исключительных случаев, когда элементы не проявляют степени окисления, равной номеру группы (например, фтор).

Оксиды состава R2O проявляют сильные основные свойства, причём их основность возрастает с увеличением порядкового номера, оксиды состава RO (за исключением BeO) проявляют основные свойства. Оксиды состава RO2, R2O5, RO3, R2O7 проявляют кислотные свойства, причём их кислотность возрастает с увеличением порядкового номера.

Элементы главных подгрупп, начиная с IV группы, образуют газообразные водородные соединения. Существуют четыре формы таких соединений. Их располагают под элементами главных подгрупп и изображают общими формулами в последовательности RH4, RH3, RH2, RH.

Соединения RH4 имеют нейтральный характер; RH3 — слабоосновный; RH2 — слабокислый; RH — сильнокислый характер.

Напомним, что периодом называют горизонтальный ряд элементов, расположенных в порядке возрастания порядковых (атомных) номеров.

В пределах периода с увеличением порядкового номера элемента:

- электроотрицательность возрастает;

- металлические свойства убывают, неметаллические возрастают;

- атомный радиус падает.

Элементы таблицы Менделеева

Щелочные и щелочноземельные элементы

К ним относятся элементы из первой и второй группы периодической таблицы. Щелочные металлы из первой группы — мягкие металлы, серебристого цвета, хорошо режутся ножом. Все они обладают одним-единственным электроном на внешней оболочке и прекрасно вступают в реакцию. Щелочноземельные металлы из второй группы также имеют серебристый оттенок. На внешнем уровне помещено по два электрона, и, соответственно, эти металлы менее охотно взаимодействуют с другими элементами. По сравнению со щелочными металлами, щелочноземельные металлы плавятся и кипят при более высоких температурах.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Щелочные металлы | Щелочноземельные металлы |

| Литий Li 3 | Бериллий Be 4 |

| Натрий Na 11 | Магний Mg 12 |

| Калий K 19 | Кальций Ca 20 |

| Рубидий Rb 37 | Стронций Sr 38 |

| Цезий Cs 55 | Барий Ba 56 |

| Франций Fr 87 | Радий Ra 88 |

Лантаниды (редкоземельные элементы) и актиниды

Лантаниды — это группа элементов, изначально обнаруженных в редко встречающихся минералах; отсюда их название «редкоземельные» элементы. Впоследствии выяснилось, что данные элементы не столь редки, как думали вначале, и поэтому редкоземельным элементам было присвоено название лантаниды. Лантаниды и актиниды занимают два блока, которые расположены под основной таблицей элементов. Обе группы включают в себя металлы; все лантаниды (за исключением прометия) нерадиоактивны; актиниды, напротив, радиоактивны.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Лантаниды | Актиниды |

| Лантан La 57 | Актиний Ac 89 |

| Церий Ce 58 | Торий Th 90 |

| Празеодимий Pr 59 | Протактиний Pa 91 |

| Неодимий Nd 60 | Уран U 92 |

| Прометий Pm 61 | Нептуний Np 93 |

| Самарий Sm 62 | Плутоний Pu 94 |

| Европий Eu 63 | Америций Am 95 |

| Гадолиний Gd 64 | Кюрий Cm 96 |

| Тербий Tb 65 | Берклий Bk 97 |

| Диспрозий Dy 66 | Калифорний Cf 98 |

| Гольмий Ho 67 | Эйнштейний Es 99 |

| Эрбий Er 68 | Фермий Fm 100 |

| Тулий Tm 69 | Менделевий Md 101 |

| Иттербий Yb 70 | Нобелий No 102 |

Галогены и благородные газы

Галогены и благородные газы объединены в группы 17 и 18 периодической таблицы. Галогены представляют собой неметаллические элементы, все они имеют семь электронов во внешней оболочке. В благородных газахвсе электроны находятся во внешней оболочке, таким образом с трудом участвуют в образовании соединений. Эти газы называют «благородными, потому что они редко вступают в реакцию с прочими элементами; т. е. ссылаются на представителей благородной касты, которые традиционно сторонились других людей в обществе.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Галогены | Благородные газы |

| Фтор F 9 | Гелий He 2 |

| Хлор Cl 17 | Неон Ne 10 |

| Бром Br 35 | Аргон Ar 18 |

| Йод I 53 | Криптон Kr 36 |

| Астат At 85 | Ксенон Xe 54 |

| — | Радон Rn 86 |

Переходные металлы

Переходные металлы занимают группы 3—12 в периодической таблице. Большинство из них плотные, твердые, с хорошей электро- и теплопроводностью. Их валентные электроны (при помощи которых они соединяются с другими элементами) находятся в нескольких электронных оболочках.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Переходные металлы |

| Скандий Sc 21 |

| Титан Ti 22 |

| Ванадий V 23 |

| Хром Cr 24 |

| Марганец Mn 25 |

| Железо Fe 26 |

| Кобальт Co 27 |

| Никель Ni 28 |

| Медь Cu 29 |

| Цинк Zn 30 |

| Иттрий Y 39 |

| Цирконий Zr 40 |

| Ниобий Nb 41 |

| Молибден Mo 42 |

| Технеций Tc 43 |

| Рутений Ru 44 |

| Родий Rh 45 |

| Палладий Pd 46 |

| Серебро Ag 47 |

| Кадмий Cd 48 |

| Лютеций Lu 71 |

| Гафний Hf 72 |

| Тантал Ta 73 |

| Вольфрам W 74 |

| Рений Re 75 |

| Осмий Os 76 |

| Иридий Ir 77 |

| Платина Pt 78 |

| Золото Au 79 |

| Ртуть Hg 80 |

| Лоуренсий Lr 103 |

| Резерфордий Rf 104 |

| Дубний Db 105 |

| Сиборгий Sg 106 |

| Борий Bh 107 |

| Хассий Hs 108 |

| Мейтнерий Mt 109 |

| Дармштадтий Ds 110 |

| Рентгений Rg 111 |

| Коперниций Cn 112 |

Металлоиды

Металлоиды занимают группы 13—16 периодической таблицы. Такие металлоиды, как бор, германий и кремний, являются полупроводниками и используются для изготовления компьютерных чипов и плат.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Металлоиды |

| Бор B 5 |

| Кремний Si 14 |

| Германий Ge 32 |

| Мышьяк As 33 |

| Сурьма Sb 51 |

| Теллур Te 52 |

| Полоний Po 84 |

Постпереходными металлами

Элементы, называемые постпереходными металлами, относятся к группам 13—15 периодической таблицы. В отличие от металлов, они не имеют блеска, а имеют матовую окраску. В сравнении с переходными металлами постпереходные металлы более мягкие, имеют более низкую температуру плавления и кипения, более высокую электроотрицательность. Их валентные электроны, с помощью которых они присоединяют другие элементы, располагаются только на внешней электронной оболочке. Элементы группы постпереходных металлов имеют гораздо более высокую температуру кипения, чем металлоиды.

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Постпереходные металлы |

| Алюминий Al 13 |

| Галлий Ga 31 |

| Индий In 49 |

| Олово Sn 50 |

| Таллий Tl 81 |

| Свинец Pb 82 |

| Висмут Bi 83 |

Неметаллы

Из всех элементов, классифицируемых как неметаллы, водород относится к 1-й группе периодической таблицы, а остальные — к группам 13—18. Неметаллы не являются хорошими проводниками тепла и электричества. Обычно при комнатной температуре они пребывают в газообразном (водород или кислород) или твердом состоянии (углерод).

Показать / Скрыть текст

| Неметаллы |

| Водород H 1 |

| Углерод C 6 |

| Азот N 7 |

| Кислород O 8 |

| Фосфор P 15 |

| Сера S 16 |

| Селен Se 34 |

| Флеровий Fl 114 |

| Унунсептий Uus 117 |

А теперь закрепите полученные знания, посмотрев видео про таблицу Менделеева и не только.

Отлично, первый шаг на пути к знаниям сделан. Теперь вы более-менее ориентируетесь в таблице Менделеева и это вам очень даже пригодится, ведь Периодическая система Менделеева является фундаментом, на котором стоит эта удивительная наука.