даша086

+10

Решено

6 лет назад

Химия

10 — 11 классы

Атомный номер металла, который обеспечивает зеленый цвет малахита.

Смотреть ответ

Ответ

2

(1 оценка)

1

![]()

Умняша69

6 лет назад

Светило науки — 3 ответа — 0 раз оказано помощи

Это конечно же медь, ее номер 29.

(1 оценка)

Ответ

0

(0 оценок)

0

ясевиндж

6 лет назад

Светило науки — 1 ответ — 0 раз оказано помощи

эта медь номер 22 правлна

(0 оценок)

Остались вопросы?

Новые вопросы по предмету Химия

Аммиак горит в хлоре,при этом образуется азот и хлороводород. Рассчитайте объемы всех газов,если сгорает 4л аммиака.

Для получения иодида меди(I) CuI к раствору соли меди(II) прибавляют иодид калия. В результате реакции выпадают осадки целевого продукта и иода …

Все на картинке.Очень нужно

Определи чем являются атомы серы (окислителем, восстановителем,окислителем и восстановителем) в реакции, уравнение которой Ca+S=CaS.

Складіть рівняння реакціі 1)CaO+SiO2 2)Na2O+HNO3 3)SO2+KOH 15 Балов СРОЧНОО

Малахит – уникальный камень, относящийся к классу карбонатов меди, применяемый в ювелирном деле и иных сферах. Добывается преимущественно на Урале. Самоцвет обладает уникальным природным малахитовым узором, который не повторяется – нет ни одного образца с идентичным рисунком.

Каковы его физические и химические свойства? Каковы стадии образования малахита и где находятся самые крупные месторождения? Относится ли он к драгоценным камням? Обладает ли целебными свойствами, какие магические характеристики ему свойственны? Кому по гороскопу показан этот камень, какое значение он имеет для представителей разных знаков зодиака? Как хранить украшения и ухаживать за ними? Можно самостоятельно отличить оригинал от подделки?

Содержание

- 1. Малахит: внешний вид, фото, физические и химические характеристики

- 2. Как образуется камень в природе?

- 3. Известные месторождения минерала в России и мире

- 4. Применение малахита

- 5. Лечебные и магические свойства полезного ископаемого

- 6. Каким знакам зодиака подходит минерал?

- 7. Как хранить малахитовые изделия и ухаживать за ними?

- 8. Как отличить натуральный природный минерал малахит от подделки?

- 9. Видео по теме статьи

- 10. Комментарии посетителей по теме статьи

Малахит: внешний вид, фото, физические и химические характеристики

Малахит – красивейшее ископаемое зеленоватого оттенка. Драгоценным камнем не считается. Он обладает уникальным рисунком и разной степенью прозрачности (см. фото). До обработки выглядит как монолитная глыба неправильной формы, включающая множество образований, спаянных между собой. Цвета этих слоев зависят от территории выработки камня. В большинстве случаев добывают зеленые самоцветы с чередующимися темными и светлыми полосами.

Разновидности малахита, которые отличаются по цвету и рисунку, и их описание:

- Лучистый. Имеет травянистый оттенок и ровные темные полосы, чередующиеся со светлыми.

- Почковидный. Темные слои представляют образования круглой формы, которые обрамляют светлые включения.

- Шелковый. Зеленоватые слои чередуются с бирюзовыми.

- Плисовый. В окраске преобладает ярко-зеленый цвет, текстура напоминает плиссировку.

- Азурмалахит и другие виды. В состав таких камней входят другие породы, это так называемый агрегат малахита, который характерен и для уральских ископаемых.

Плисовый малахит и другие его разновидности – один из главных минералов меди (Cu, атомный номер – 29, удельная теплоемкость – 0,385 кДж/(кг·К)), содержащий чуть менее 60% вещества без дополнительных примесей. Именно его ионы обеспечивают окраску самоцвета.

Химическая формула вещества: CuCO3·Сu(OH)2. В случае нагревания до нескольких сотен градусов чернеет и образует воду. Растворяется в различных кислотах с выделением CO2 и в аммиаке, придавая ему голубоватый оттенок.

Физические свойства:

- твердость по шкале Мооса – 3,5–4 балла;

- степень прозрачности – прозрачный или полупрозрачный;

- варианты расцветки камня – зеленая, светло- и темно-зеленая (в том числе в разрезе);

- оттенок черты – светло-зеленый;

- характер блеска – матовый, стеклянный, шелковый, тусклый;

- спайность – хорошая, совершенная;

- излом – занозистый, неровный, близок к раковистому;

- прочность материала – хрупкий;

- плотность – 3,6–4,05 г/см3;

- удельная теплоемкость – 288–372 Дж/(кг·К);

- радиоактивность – отсутствует.

Существует мнение, что наличие коричневых полос в структуре камня указывает на его искусственную природу. Однако с этим нельзя согласиться. Красновато-коричневые включения, как правило, свидетельствуют о присутствии в камне хризоколлы или куприта.

Как образуется камень в природе?

Малахит образуется только на тех участках, где окисляются медные сульфитные залежи, особенно в тех случаях, когда они расположены в известняках или первичные руды включают большое количество карбонатов. Процесс образования малахита может происходить с замещением карбонатов или же в процессе восполнения пустот с формированием внутри них колломорфных структур.

Поскольку в растворах у поверхности известняков и карбонатов кальция и магния создается щелочная среда, контактирующие с ними сульфаты меди разлагаются под воздействием воды (процесс гидролиза). Также карбонаты меди могут образовываться посредством реакции сульфата или гидрата меди с раствором, обогащенным углекислотой из воздуха. Нередко формируются псевдоморфозы зеленого цвета из малахита по азуриту, самородной меди и другим структурам.

Известные месторождения минерала в России и мире

В России месторождения малахита в большинстве своем полностью исчерпались. Горную породу добывают на Урале. Многие российские месторождения в полной мере выработаны и прекратили свою деятельность, запасы минерала обнаружены вновь только в Коровинско-Решетниковском, с которым связывают возрождение добычи уральского малахита в будущем.

Сейчас главной территорией добычи малахита является Республика Конго (Африка). Этот минерал отличается от уральского по структуре: он имеет более крупные правильные концентрические кольца с контрастными переходами светлых областей в темные. По весу на каждые 10 тыс. т добываемой руды приходится примерно 100 кг поделочного материала, среди этого объема находят поистине уникальные образцы для частных коллекций и декоративные экземпляры высшего качества.

Качественные образцы встречаются в Западной Европе и странах СНГ. Месторождения открыты во Франции, Англии, Германии, на Алтае и в Казахстане. Однако эти породы не так ценны, как уральский малахит.

Применение малахита

Плотные минералы глубокого зеленого цвета с восхитительным узором весьма дорогостоящие и используются для изготовления роскошных предметов декора и оформления интерьера – ваз, облицовки мебели, шкатулок и т. д. Из таких же камней создают произведения ювелирного искусства – броши, бусы, кулоны, кольца, браслеты и т. д., хотя драгоценными они не являются.

Примером самого монументального изделия из малахита являются колонны Исаакиевского собора в Санкт-Петербурге – они облицованы тонкими пластинами минерала. Древнейшая малахитовая ваза необычайной красоты представлена в Минералогическом музее имени Ферсмана в Москве – она украшает центр зала.

Из мелкой минеральной крошки изготавливают природный зеленый пигмент. С давних времен малахит использовался для получения меди.

Лечебные и магические свойства полезного ископаемого

Малахит – один из самых мощных и надежных талисманов и оберегов от различных недугов. Об этом стало известно еще во времена существования Древнего Египта. Во время эпидемии холеры местные лекари обнаружили интересный факт: людей, участвующих в добыче малахита, это заболевание обошло стороной.

Лечебные свойства малахита:

- наилучшим образом влияет на нервную систему;

- малахитовые украшения помогают привести в норму давление;

- минерал полезен при судорожных состояниях, эпилептических и астматических приступах;

- малахит используют и в онкологии: литотерапевты полагают, что он способствует замедлению роста и распространения злокачественных клеток;

- ускоряет сращивание костей, заживление кожных покровов после переломов и других травм;

- при ношении малахитового браслета его владелец будет надежно защищен от возникновения проявлений аллергии и кожных патологий;

- облегчает симптоматику у женщин во время менструаций и в период родовой деятельности.

Эзотерики полагают, что есть у малахита и магические свойства. Существует даже мнение о том, что этот камень способен сделать человека невидимкой для окружающих и может научить птичьему языку и общению с животным миром. Считается, что дар общения с природой проявляется, если выпить воды из кубка, выполненного из самоцвета.

Малахит позволяет наладить хорошие отношения с людьми. Он поможет справиться с неконтролируемыми перепадами настроения, пережить стресс и депрессию. Камень улучшает память, стимулирует умственную деятельность, наделяет своего владельца даром красноречия. Если человек носит его при себе, он быстрее и полнее усваивает информацию, поэтому самоцветом следует обзавестись студентам, школьникам и других людям, чья деятельность напрямую связана с выступлениями на публике.

Камень чувствует своего владельца, улавливает его настроение и меняет цвет при изменении эмоционального состояния. Он дарует надежную защиту путешественникам и другим людям, которые находятся в пути. Водителям в поездки следует всегда брать с собой малахит.

Наиболее мощной энергетикой обладают украшения из малахита, оправленные в серебро. Именно этот металл способен усилить магические свойства камня. Такое украшение защитит от злых сил, поможет обрести уверенность в себе, покажет краткий путь в достижении целей.

Малахит не следует носить авантюрным и рисковым личностям. Камень способен усиливать страсть к риску, что может не лучшим образом сказаться на жизни и судьбе такого человека.

Каким знакам зодиака подходит минерал?

Малахит полностью подходит лишь небольшому количеству знаков зодиака. Некоторым лицам он противопоказан по гороскопу. Камень в наибольшей степени подходит Тельцам. С помощью минерала представители этого знака смогут погрузиться в гармоничные отношения с самими собой и окружающим миром. Малахит подарит спокойствие и умиротворение в душе. Тельцы смогут избавиться от негативных сторон своей натуры и усилить хорошие качества. Камень защитит от недоброжелателей и колдовства, направленного на ухудшение качества жизни и разрушение семейных уз хозяина малахита.

Весам также подходит этот камень. Он поддержит в принятии жизненно важных решений, подтолкнет в правильную сторону при нерешительности и сомнениях.

Львы могут носить малахит – природный минерал наградит представителя этого знака уверенностью в себе и душевным спокойствием, комфортом. Камень поможет гасить приступы неконтролируемой агрессии и гнева, поможет найти выход даже из самой сложной жизненной ситуации, добавит уверенности в себе.

Скорпионы смогут избавиться от негативных черт своего характера – излишней медлительности и стеснительности. Застенчивый хозяин камня найдет общий язык с окружающими, перестанет сомневаться в своих силах и обретет уверенность в том, что он все делает правильно.

Малахит абсолютно не подходит Девам и Ракам. Это связано с тем, что такие знаки зодиака не совпадают с минералом на энергетическом уровне, поэтому от ношения малахитовых украшений стоит воздержаться.

Как хранить малахитовые изделия и ухаживать за ними?

Чтобы малахит сохранял свою красоту, а его узоры оставались такими же выраженными, требуется правильно ухаживать за камнем. Уход должен быть деликатным. Нужно оберегать изделие от возможных ударов и падений. Исключено воздействие повышенных температур. Необходимо исключить контакты с агрессивными веществами при использовании и очищении малахита. Устранять загрязнения с камня следует исключительно мягкой тканью, смоченной теплой водой. Для этой цели идеально подойдет хлопковая салфетка.

Хранить малахит необходимо в отдельной шкатулке, предназначенной для мягких камней, – так сохранятся его целостность, внешний вид и энергия. Следует снимать изделия с минералом во время приготовления пищи, уборки, при посещении бани и сауны.

Как отличить натуральный природный минерал малахит от подделки?

Малахит ценился на протяжении долгих лет и продолжает цениться и в настоящее время, поскольку многие уральские шахты давно отработаны и закрыты. Количество предложений по продаже камня значительно снизилось, и цены на него существенно возросли. В силу этого часто находятся недобросовестные продавцы, пытающиеся реализовать подделку вместо природного минерала.

Способы отличить натуральный камень от подделки:

- Стоимость изделия. Малахит натурального происхождения никогда не будет стоить дешево. Однако качественный искусственный минерал также может быть высоко оценен, поэтому вопрос выбора украшения по этому признаку стоит очень остро. Иногда даже известные и проверенные ювелирные магазины не могут гарантировать, что не реализуют имитацию.

- Внешний вид минерала. Опытные мастера ювелирного дела могут визуально отличить искусственный малахит от натурального самоцвета, даже не беря его в руки. Главная особенность – рисунок. Подделывать малахит очень сложно, поскольку он обладает неповторимым узором. Каждое изделие из натурального камня уникально. Искусственные экземпляры похожи друг на друга и имеют идентичные рисунки на поверхности.

- Цвет камня. Как правило, подделки включают всего 3 оттенка – от светлого до темного. Присмотревшись к натуральному камню, можно определить массу образований разных расцветок, которые плавно переходят друг в друга.

| Malachite | |

|---|---|

Malachite from the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Cu2CO3(OH)2 |

| IMA symbol | Mlc[1] |

| Strunz classification | 5.BA.10 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/a |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 221.1 g/mol |

| Color | Bright green, dark green, blackish green, with crystals deeper shades of green, even very dark to nearly black commonly banded in masses; green to yellowish green in transmitted light |

| Crystal habit | Massive, botryoidal, stalactitic, crystals are acicular to tabular prismatic |

| Twinning | Common as contact or penetration twins on {100} and {201}. Polysynthetic twinning also present. |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {201} fair on {010} |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3.5–4 |

| Luster | Adamantine to vitreous; silky if fibrous; dull to earthy if massive |

| Streak | light green |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 3.6–4 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (–) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.655 nβ = 1.875 nγ = 1.909 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.254 |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Malachite is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the formula Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often forms botryoidal, fibrous, or stalagmitic masses, in fractures and deep, underground spaces, where the water table and hydrothermal fluids provide the means for chemical precipitation. Individual crystals are rare, but occur as slender to acicular prisms. Pseudomorphs after more tabular or blocky azurite crystals also occur.[5]

Etymology and history[edit]

The entrance to the Neolithic era malachite mine complex on the Great Orme, Wales

The stone’s name derives (via Latin: molochītis, Middle French: melochite, and Middle English melochites) from Greek Μολοχίτης λίθος molochites lithos, «mallow-green stone», from μολόχη molochē, variant of μαλάχη malāchē, «mallow».[6] The mineral was given this name due to its resemblance to the leaves of the mallow plant.[7]

Malachite was mined from deposits near the Isthmus of Suez and the Sinai as early as 4000 BCE.[8]

It was extensively mined at the Great Orme Mines in Britain 3,800 years ago, using stone and bone tools. Archaeological evidence indicates that mining activity ended c. 600 BCE, with up to 1,760 tonnes of copper being produced from the mined malachite.[9][10]

Archaeological evidence indicates that the mineral has been mined and smelted to obtain copper at Timna Valley in Israel for more than 3,000 years.[11] Since then, malachite has been used as both an ornamental stone and as a gemstone.

The use of azurite and malachite as copper ore indicators led indirectly to the name of the element nickel in the English language. Nickeline, a principal ore of nickel that is also known as niccolite, weathers at the surface into a green mineral (annabergite) that resembles malachite. This resemblance resulted in occasional attempts to smelt nickeline in the belief that it was copper ore, but such attempts always ended in failure due to high smelting temperatures needed to reduce nickel. In Germany this deceptive mineral came to be known as kupfernickel, literally «copper demon.» The Swedish alchemist Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (who had been trained by Georg Brandt, the discoverer of the nickel-like metal cobalt) realized that there was probably a new metal hiding within the kupfernickel ore, and in 1751 he succeeded in smelting kupfernickel to produce a previously unknown (except in certain meteorites) silvery white, iron-like metal. Logically, Cronstedt named his new metal after the nickel part of kupfernickel.

Occurrence[edit]

Malachite in the walls of Outokumpu’s old mine.

Malachite often results from the supergene weathering and oxidation of primary sulfidic copper ores, and is often found with azurite (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2), goethite, and calcite. Except for its vibrant green color, the properties of malachite are similar to those of azurite and aggregates of the two minerals occur frequently. Malachite is more common than azurite and is typically associated with copper deposits around limestones, the source of the carbonate.

Large quantities of malachite have been mined in the Urals, Russia. Ural malachite is not being mined at present,[12] but G.N Vertushkova reports the possible discovery of new deposits of malachite in the Urals.[13] It is found worldwide including in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Gabon; Zambia; Tsumeb, Namibia; Mexico; Broken Hill, New South Wales; Burra, South Australia; Lyon, France; Timna Valley, Israel; and the Southwestern United States, most notably in Arizona.[14]

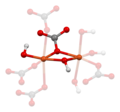

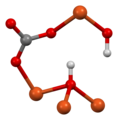

Structure[edit]

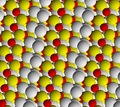

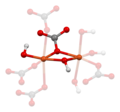

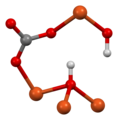

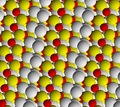

Malachite crystallizes in the monoclinic system. The structure consists of chains of alternating Cu2+ ions and OH− ions, with a net positive charge, woven between isolated triangular CO32− ions. Thus each copper ion is conjugated to two hydroxyl ions and two carbonate ions; each hydroxyl ion is conjugated with two copper ions; and each carbonate ion is conjugated with six copper ions.[15][16]

-

View along c axis of the crystal structure of malachite

-

View along a axis of malachite crystal structure

-

View along b axis of malachite crystal structure

-

-

-

Coordination environment of copper #1

-

Coordination environment of copper #2

-

Coordination environment of hydroxide #2

Use[edit]

Malachite was used as a mineral pigment in green paints from antiquity until c. 1800.[18] The pigment is moderately lightfast, sensitive to acids, and varying in color. This natural form of green pigment has been replaced by its synthetic form, verditer, among other synthetic greens.

Malachite is also used for decorative purposes, such as in the Malachite Room in the Hermitage Museum,[19] which features a huge malachite vase, and the Malachite Room in Castillo de Chapultepec in Mexico City.[20] Another example is the Demidov Vase, part of the former Demidov family collection, and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21] «The Tazza», a large malachite vase, one of the largest pieces of malachite in North America and a gift from Tsar Nicholas II, stands as the focal point in the centre of the room of Linda Hall Library. In the time of Tsar Nicolas I decorative pieces with malachite were among the most popular diplomatic gifts.[22] It was used in China as far back as the Eastern Zhou period.[23] The base of FIFA World Cup Trophy has two layers of malachite.

Symbolism and superstitions[edit]

A 17th-century Spanish superstition held that having a child wear a lozenge of malachite would help them sleep, and keep evil spirits at bay.[24] Marbodus recommended malachite as a talisman for young people because of its protective qualities and its ability to help with sleep.[25] It has also historically been worn for protection from lightning and contagious diseases and for health, success, and constancy in the affections.[25] During the Middle Ages it was customary to wear it engraved with a figure or symbol of the Sun to maintain health and to avert depression to which Capricorns were considered vulnerable.[25]

In ancient Egypt the colour green (wadj) was associated with death and the power of resurrection as well as new life and fertility. Ancient Egyptians believed that the afterlife contained an eternal paradise, referred to as the «Field of Malachite», which resembled their lives but with no pain or suffering.[26]

Ore uses[edit]

Simple methods of copper ore extraction from malachite involved thermodynamic processes such as smelting.[27] This reaction involves the addition of heat and a carbon, causing the carbonate to decompose leaving copper oxide and an additional carbon source such as coal converts the copper oxide into copper metal.[27][28]

The basic word equation for this reaction is:

Copper carbonate + heat → carbon dioxide + copper oxide (color changes from green to black).[27][28]

Copper oxide + carbon → carbon dioxide + copper (color change from black to copper colored).[27][28]

Malachite is a low grade copper ore, however, due to increase demand for metals, more economic processing such as hydrometallurgical methods (using aqueous solutions such as sulfuric acid) are being used as malachite is readily soluble in dilute acids.[29][30] Sulfuric acid is the most common leaching agent for copper oxide ores like malachite and eliminates the need for smelting processes.[31]

The chemical equation for sulfuric acid leaching of copper ore from malachite is as follows:[31]

-

malachiteCu2(OH)2CO3 + sulfuric acid2H2SO4 → copper sulfate2CuSO4 + carbon dioxideCO2 + water3H2O

(Reaction 1)

Health and environmental concerns[edit]

Mining for malachite for ornamental or copper ore purposes involves open-pit mining or underground mining depending on the grade of the ore deposits.[32] Open-pit and underground mining practices can cause environmental degradation through habitat and biodiversity loss.[33][34] Acid mine drainage can contaminate water and food sources to negatively impact human health if improperly managed or if leaks from tailing ponds occur.[34][35] The risk of health and environmental impacts of both traditional metallurgy and newer methods of hydrometallurgy are both significant,[34] however, water conservation and waste management practices for hydrometallurgy processes for ore extraction, such as for malachite, are stricter and relatively more sustainable.[36] New research is also being conducted on better alternatives to methods such as sulfuric acid leaching which has high environmental impacts, even under hydrometallurgy regulation standards and innovation.[31]

Gallery[edit]

-

Slice through a double stalactite, from Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size 5.9 × 3.9 × 0.7 cm.

-

-

Malachite stalactites (to 9 cm height), from Kasompi Mine, Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size: 21.6×16.0×11.9 cm.

-

Malachite, image taken under a stereoscopic microscope

-

Elephant carved from malachite. Length 11 cm.

See also[edit]

- Aventurine

- Brochantite

- Chrysocolla

- Dioptase

- Green pigments

- List of inorganic pigments

- Plancheite

- Pseudomalachite

- Turquoise

- Verdigris

References[edit]

- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). «IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols». Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM…85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (2003). «Malachite» (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. V (Borates, Carbonates, Sulfates). Chantilly, Virginia: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209740.

- ^ Malachite. Webmineral

- ^ a b Malachite. Mindat

- ^ Malachite, Dictionary.com

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «malachite». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Susarla, S.M (2016). «The colourful history of malachite green: from ancient Egypt to modern surgery». International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 46 (3): 401–403. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.022. PMID 27771151.

- ^ Johnson, Ben, ed. (2014). «The Great Orme Mines». Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Ruggeri, Amanda (21 April 2016). «The Ancient Copper Mines Dug By Bronze Age Children». BBC. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Parr, Peter J. (1974). «Review of ‘Timma: Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines’ by Beno Rothenberg Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 223–224

- ^ Куда делись символы России? Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Argumenty i Fakty (24 May 2006)

- ^ Somin, L. M. Тайны седого Урала. Малахит. oldrushistory.ru

- ^ Mindat map with over 8500 locations. mindat.org

- ^ Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. (1993). Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) (21st ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 417. ISBN 047157452X.

- ^ «Malachite». American Mineralogical Crystal Structure Database. Department of Geology, University of Arizona. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ «The Red Queen and Her Sisters: Women of Power in Golden Kingdoms». www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Gettens, R.J. and Fitzhugh, E. W. (1993) «Malachite and Green Verditer», pp. 183–202 in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0894682601

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2011). «Малахитовые залы Петербурга, России, Европы… / Malachite salon of St.-Petersburg, Russia, Europe…» // Блистательный Петербург. Роль архитекторов ХIХ века в создании неповторимого облика города. Материалы научно-практической конференции. Кафедра. Сб. науч. Ст. – СПб.: Государственный музей-памятник «Исаакиевский собор», 2011. – С. 23-49.

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2013). «La produzione in malachite dei Demidov: sulle trace degli oggetti alla prima esposizione universale / I Demidoff fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e prestigio di une famiglia in Europa dal XVIII al XX secolo. – P. 151-176, 9 tav». // I Demidoff Fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e Prestigio di Une Famiglia in Europa Dal XVIII al XX Secolo. A Cura di Lucia Tonini. Cultura e Memoria, Vol. 50. – Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2013.

- ^ Monumental vase lapidary work: early 19th century; pedestal and mounts: 1819 Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Будрина, Людмила (2020). Малахитовая дипломатия. Екатеринбург: Кабинетный ученый. p. 208. ISBN 978-5-6044025-1-1.

- ^ Langhals, Heinz; Bathelt, Daniela (1 December 2003). «The Restoration of the Largest Archaelogical Discovery—a Chemical Problem: Conservation of the Polychromy of the Chinese Terracotta Army in Lintong». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 42 (46): 5676–5681. doi:10.1002/anie.200301633. PMID 14661198.

- ^ The Illustrated Book of Signs and Symbols by Miranda Bruce-Mitford, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 1996, p. 41

- ^ a b c The Book of Talismans, Amulets and Zodiacal Gems, by William Thomas and Kate Pavitt, [1922], p. 254

- ^ Hill, J (2010). «Meaning of green in ancient Egypt». Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Cris E.; Yee, Gordon T.; Eddleton, Jeannine E. (2004-12-01). «Copper Metal from Malachite circa 4000 B.C.E.» Journal of Chemical Education. 81 (12): 1777. Bibcode:2004JChEd..81.1777J. doi:10.1021/ed081p1777. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c Day, Jo; Kobik, Maggie (2019-09-30), «Reconstructing a Bronze Age Kiln from Priniatikos Pyrgos, Crete», Experimental Archaeology: Making, Understanding, Story-telling, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, pp. 63–72, doi:10.2307/j.ctvpmw4g8.11, ISBN 978-1-78969-320-1, S2CID 210629355, retrieved 2021-02-25

- ^ Ata, O. N.; Yalap, H. (2007-06-01). «Optimization of Copper Leaching from Ore Containing Malachite». Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly. 46 (2): 107–114. Bibcode:2007CaMQ…46..107A. doi:10.1179/cmq.2007.46.2.107. ISSN 0008-4433. S2CID 98163205.

- ^ «Malachite». www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ a b c Shabani, M. A.; Irannajad, M.; Azadmehr, A. R. (2012-09-01). «Investigation on leaching of malachite by citric acid». International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy, and Materials. 19 (9): 782–786. Bibcode:2012IJMMM..19..782S. doi:10.1007/s12613-012-0628-9. ISSN 1869-103X. S2CID 96128268.

- ^ «Malachite». www.mine-engineer.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Monjezi, M.; Shahriar, K.; Dehghani, H.; Samimi Namin, F. (2009-07-01). «Environmental impact assessment of open pit mining in Iran». Environmental Geology. 58 (1): 205–216. Bibcode:2009EnGeo..58..205M. doi:10.1007/s00254-008-1509-4. ISSN 1432-0495. S2CID 128616763.

- ^ a b c Salomons, W. (1995-01-01). «Environmental impact of metals derived from mining activities: Processes, predictions, prevention». Journal of Geochemical Exploration. Heavy Metal Aspects of Mining Pollution and Its Remediation. 52 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1016/0375-6742(94)00039-E. ISSN 0375-6742.

- ^ «Environmental Impact of Sulfuric Acid Leaching». www.savethesantacruzaquifer.info. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Conard, Bruce R. (1992-06-01). «The role of hydrometallurgy in achieving sustainable development». Hydrometallurgy. Hydrometallurgy, Theory and Practice Proceedings of the Ernest Peters International Symposium. Part B. 30 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1016/0304-386X(92)90074-A. ISSN 0304-386X.

External links[edit]

![]()

Look up malachite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

![]()

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malachite.

- Virtual tour of the Malachite Room

- Malachite, Colourlex

- Malachite in art and malachite diplomacy

| Malachite | |

|---|---|

Malachite from the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Cu2CO3(OH)2 |

| IMA symbol | Mlc[1] |

| Strunz classification | 5.BA.10 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | P21/a |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 221.1 g/mol |

| Color | Bright green, dark green, blackish green, with crystals deeper shades of green, even very dark to nearly black commonly banded in masses; green to yellowish green in transmitted light |

| Crystal habit | Massive, botryoidal, stalactitic, crystals are acicular to tabular prismatic |

| Twinning | Common as contact or penetration twins on {100} and {201}. Polysynthetic twinning also present. |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {201} fair on {010} |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3.5–4 |

| Luster | Adamantine to vitreous; silky if fibrous; dull to earthy if massive |

| Streak | light green |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 3.6–4 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (–) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.655 nβ = 1.875 nγ = 1.909 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.254 |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Malachite is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the formula Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often forms botryoidal, fibrous, or stalagmitic masses, in fractures and deep, underground spaces, where the water table and hydrothermal fluids provide the means for chemical precipitation. Individual crystals are rare, but occur as slender to acicular prisms. Pseudomorphs after more tabular or blocky azurite crystals also occur.[5]

Etymology and history[edit]

The entrance to the Neolithic era malachite mine complex on the Great Orme, Wales

The stone’s name derives (via Latin: molochītis, Middle French: melochite, and Middle English melochites) from Greek Μολοχίτης λίθος molochites lithos, «mallow-green stone», from μολόχη molochē, variant of μαλάχη malāchē, «mallow».[6] The mineral was given this name due to its resemblance to the leaves of the mallow plant.[7]

Malachite was mined from deposits near the Isthmus of Suez and the Sinai as early as 4000 BCE.[8]

It was extensively mined at the Great Orme Mines in Britain 3,800 years ago, using stone and bone tools. Archaeological evidence indicates that mining activity ended c. 600 BCE, with up to 1,760 tonnes of copper being produced from the mined malachite.[9][10]

Archaeological evidence indicates that the mineral has been mined and smelted to obtain copper at Timna Valley in Israel for more than 3,000 years.[11] Since then, malachite has been used as both an ornamental stone and as a gemstone.

The use of azurite and malachite as copper ore indicators led indirectly to the name of the element nickel in the English language. Nickeline, a principal ore of nickel that is also known as niccolite, weathers at the surface into a green mineral (annabergite) that resembles malachite. This resemblance resulted in occasional attempts to smelt nickeline in the belief that it was copper ore, but such attempts always ended in failure due to high smelting temperatures needed to reduce nickel. In Germany this deceptive mineral came to be known as kupfernickel, literally «copper demon.» The Swedish alchemist Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (who had been trained by Georg Brandt, the discoverer of the nickel-like metal cobalt) realized that there was probably a new metal hiding within the kupfernickel ore, and in 1751 he succeeded in smelting kupfernickel to produce a previously unknown (except in certain meteorites) silvery white, iron-like metal. Logically, Cronstedt named his new metal after the nickel part of kupfernickel.

Occurrence[edit]

Malachite in the walls of Outokumpu’s old mine.

Malachite often results from the supergene weathering and oxidation of primary sulfidic copper ores, and is often found with azurite (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2), goethite, and calcite. Except for its vibrant green color, the properties of malachite are similar to those of azurite and aggregates of the two minerals occur frequently. Malachite is more common than azurite and is typically associated with copper deposits around limestones, the source of the carbonate.

Large quantities of malachite have been mined in the Urals, Russia. Ural malachite is not being mined at present,[12] but G.N Vertushkova reports the possible discovery of new deposits of malachite in the Urals.[13] It is found worldwide including in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Gabon; Zambia; Tsumeb, Namibia; Mexico; Broken Hill, New South Wales; Burra, South Australia; Lyon, France; Timna Valley, Israel; and the Southwestern United States, most notably in Arizona.[14]

Structure[edit]

Malachite crystallizes in the monoclinic system. The structure consists of chains of alternating Cu2+ ions and OH− ions, with a net positive charge, woven between isolated triangular CO32− ions. Thus each copper ion is conjugated to two hydroxyl ions and two carbonate ions; each hydroxyl ion is conjugated with two copper ions; and each carbonate ion is conjugated with six copper ions.[15][16]

-

View along c axis of the crystal structure of malachite

-

View along a axis of malachite crystal structure

-

View along b axis of malachite crystal structure

-

-

-

Coordination environment of copper #1

-

Coordination environment of copper #2

-

Coordination environment of hydroxide #2

Use[edit]

Malachite was used as a mineral pigment in green paints from antiquity until c. 1800.[18] The pigment is moderately lightfast, sensitive to acids, and varying in color. This natural form of green pigment has been replaced by its synthetic form, verditer, among other synthetic greens.

Malachite is also used for decorative purposes, such as in the Malachite Room in the Hermitage Museum,[19] which features a huge malachite vase, and the Malachite Room in Castillo de Chapultepec in Mexico City.[20] Another example is the Demidov Vase, part of the former Demidov family collection, and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21] «The Tazza», a large malachite vase, one of the largest pieces of malachite in North America and a gift from Tsar Nicholas II, stands as the focal point in the centre of the room of Linda Hall Library. In the time of Tsar Nicolas I decorative pieces with malachite were among the most popular diplomatic gifts.[22] It was used in China as far back as the Eastern Zhou period.[23] The base of FIFA World Cup Trophy has two layers of malachite.

Symbolism and superstitions[edit]

A 17th-century Spanish superstition held that having a child wear a lozenge of malachite would help them sleep, and keep evil spirits at bay.[24] Marbodus recommended malachite as a talisman for young people because of its protective qualities and its ability to help with sleep.[25] It has also historically been worn for protection from lightning and contagious diseases and for health, success, and constancy in the affections.[25] During the Middle Ages it was customary to wear it engraved with a figure or symbol of the Sun to maintain health and to avert depression to which Capricorns were considered vulnerable.[25]

In ancient Egypt the colour green (wadj) was associated with death and the power of resurrection as well as new life and fertility. Ancient Egyptians believed that the afterlife contained an eternal paradise, referred to as the «Field of Malachite», which resembled their lives but with no pain or suffering.[26]

Ore uses[edit]

Simple methods of copper ore extraction from malachite involved thermodynamic processes such as smelting.[27] This reaction involves the addition of heat and a carbon, causing the carbonate to decompose leaving copper oxide and an additional carbon source such as coal converts the copper oxide into copper metal.[27][28]

The basic word equation for this reaction is:

Copper carbonate + heat → carbon dioxide + copper oxide (color changes from green to black).[27][28]

Copper oxide + carbon → carbon dioxide + copper (color change from black to copper colored).[27][28]

Malachite is a low grade copper ore, however, due to increase demand for metals, more economic processing such as hydrometallurgical methods (using aqueous solutions such as sulfuric acid) are being used as malachite is readily soluble in dilute acids.[29][30] Sulfuric acid is the most common leaching agent for copper oxide ores like malachite and eliminates the need for smelting processes.[31]

The chemical equation for sulfuric acid leaching of copper ore from malachite is as follows:[31]

-

malachiteCu2(OH)2CO3 + sulfuric acid2H2SO4 → copper sulfate2CuSO4 + carbon dioxideCO2 + water3H2O

(Reaction 1)

Health and environmental concerns[edit]

Mining for malachite for ornamental or copper ore purposes involves open-pit mining or underground mining depending on the grade of the ore deposits.[32] Open-pit and underground mining practices can cause environmental degradation through habitat and biodiversity loss.[33][34] Acid mine drainage can contaminate water and food sources to negatively impact human health if improperly managed or if leaks from tailing ponds occur.[34][35] The risk of health and environmental impacts of both traditional metallurgy and newer methods of hydrometallurgy are both significant,[34] however, water conservation and waste management practices for hydrometallurgy processes for ore extraction, such as for malachite, are stricter and relatively more sustainable.[36] New research is also being conducted on better alternatives to methods such as sulfuric acid leaching which has high environmental impacts, even under hydrometallurgy regulation standards and innovation.[31]

Gallery[edit]

-

Slice through a double stalactite, from Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size 5.9 × 3.9 × 0.7 cm.

-

-

Malachite stalactites (to 9 cm height), from Kasompi Mine, Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Size: 21.6×16.0×11.9 cm.

-

Malachite, image taken under a stereoscopic microscope

-

Elephant carved from malachite. Length 11 cm.

See also[edit]

- Aventurine

- Brochantite

- Chrysocolla

- Dioptase

- Green pigments

- List of inorganic pigments

- Plancheite

- Pseudomalachite

- Turquoise

- Verdigris

References[edit]

- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). «IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols». Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM…85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (2003). «Malachite» (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. V (Borates, Carbonates, Sulfates). Chantilly, Virginia: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209740.

- ^ Malachite. Webmineral

- ^ a b Malachite. Mindat

- ^ Malachite, Dictionary.com

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «malachite». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Susarla, S.M (2016). «The colourful history of malachite green: from ancient Egypt to modern surgery». International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 46 (3): 401–403. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.022. PMID 27771151.

- ^ Johnson, Ben, ed. (2014). «The Great Orme Mines». Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Ruggeri, Amanda (21 April 2016). «The Ancient Copper Mines Dug By Bronze Age Children». BBC. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- ^ Parr, Peter J. (1974). «Review of ‘Timma: Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines’ by Beno Rothenberg Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 223–224

- ^ Куда делись символы России? Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Argumenty i Fakty (24 May 2006)

- ^ Somin, L. M. Тайны седого Урала. Малахит. oldrushistory.ru

- ^ Mindat map with over 8500 locations. mindat.org

- ^ Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. (1993). Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) (21st ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 417. ISBN 047157452X.

- ^ «Malachite». American Mineralogical Crystal Structure Database. Department of Geology, University of Arizona. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ «The Red Queen and Her Sisters: Women of Power in Golden Kingdoms». www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Gettens, R.J. and Fitzhugh, E. W. (1993) «Malachite and Green Verditer», pp. 183–202 in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0894682601

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2011). «Малахитовые залы Петербурга, России, Европы… / Malachite salon of St.-Petersburg, Russia, Europe…» // Блистательный Петербург. Роль архитекторов ХIХ века в создании неповторимого облика города. Материалы научно-практической конференции. Кафедра. Сб. науч. Ст. – СПб.: Государственный музей-памятник «Исаакиевский собор», 2011. – С. 23-49.

- ^ Budrina, Ludmila (January 2013). «La produzione in malachite dei Demidov: sulle trace degli oggetti alla prima esposizione universale / I Demidoff fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e prestigio di une famiglia in Europa dal XVIII al XX secolo. – P. 151-176, 9 tav». // I Demidoff Fra Russia e Italia. Gusto e Prestigio di Une Famiglia in Europa Dal XVIII al XX Secolo. A Cura di Lucia Tonini. Cultura e Memoria, Vol. 50. – Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2013.

- ^ Monumental vase lapidary work: early 19th century; pedestal and mounts: 1819 Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Будрина, Людмила (2020). Малахитовая дипломатия. Екатеринбург: Кабинетный ученый. p. 208. ISBN 978-5-6044025-1-1.

- ^ Langhals, Heinz; Bathelt, Daniela (1 December 2003). «The Restoration of the Largest Archaelogical Discovery—a Chemical Problem: Conservation of the Polychromy of the Chinese Terracotta Army in Lintong». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 42 (46): 5676–5681. doi:10.1002/anie.200301633. PMID 14661198.

- ^ The Illustrated Book of Signs and Symbols by Miranda Bruce-Mitford, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, 1996, p. 41

- ^ a b c The Book of Talismans, Amulets and Zodiacal Gems, by William Thomas and Kate Pavitt, [1922], p. 254

- ^ Hill, J (2010). «Meaning of green in ancient Egypt». Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Cris E.; Yee, Gordon T.; Eddleton, Jeannine E. (2004-12-01). «Copper Metal from Malachite circa 4000 B.C.E.» Journal of Chemical Education. 81 (12): 1777. Bibcode:2004JChEd..81.1777J. doi:10.1021/ed081p1777. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c Day, Jo; Kobik, Maggie (2019-09-30), «Reconstructing a Bronze Age Kiln from Priniatikos Pyrgos, Crete», Experimental Archaeology: Making, Understanding, Story-telling, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, pp. 63–72, doi:10.2307/j.ctvpmw4g8.11, ISBN 978-1-78969-320-1, S2CID 210629355, retrieved 2021-02-25

- ^ Ata, O. N.; Yalap, H. (2007-06-01). «Optimization of Copper Leaching from Ore Containing Malachite». Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly. 46 (2): 107–114. Bibcode:2007CaMQ…46..107A. doi:10.1179/cmq.2007.46.2.107. ISSN 0008-4433. S2CID 98163205.

- ^ «Malachite». www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ a b c Shabani, M. A.; Irannajad, M.; Azadmehr, A. R. (2012-09-01). «Investigation on leaching of malachite by citric acid». International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy, and Materials. 19 (9): 782–786. Bibcode:2012IJMMM..19..782S. doi:10.1007/s12613-012-0628-9. ISSN 1869-103X. S2CID 96128268.

- ^ «Malachite». www.mine-engineer.com. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Monjezi, M.; Shahriar, K.; Dehghani, H.; Samimi Namin, F. (2009-07-01). «Environmental impact assessment of open pit mining in Iran». Environmental Geology. 58 (1): 205–216. Bibcode:2009EnGeo..58..205M. doi:10.1007/s00254-008-1509-4. ISSN 1432-0495. S2CID 128616763.

- ^ a b c Salomons, W. (1995-01-01). «Environmental impact of metals derived from mining activities: Processes, predictions, prevention». Journal of Geochemical Exploration. Heavy Metal Aspects of Mining Pollution and Its Remediation. 52 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1016/0375-6742(94)00039-E. ISSN 0375-6742.

- ^ «Environmental Impact of Sulfuric Acid Leaching». www.savethesantacruzaquifer.info. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Conard, Bruce R. (1992-06-01). «The role of hydrometallurgy in achieving sustainable development». Hydrometallurgy. Hydrometallurgy, Theory and Practice Proceedings of the Ernest Peters International Symposium. Part B. 30 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1016/0304-386X(92)90074-A. ISSN 0304-386X.

External links[edit]

![]()

Look up malachite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

![]()

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malachite.

- Virtual tour of the Malachite Room

- Malachite, Colourlex

- Malachite in art and malachite diplomacy