В уроке 1 «Схема строения атомов» из курса «Химия для чайников» рассмотрим основы строение атома и состав атомного ядра; выясним, что такое атомная единица массы, порядковый номер атома и атомная масса элемента. Обязательно просмотрите основные понятия и определения к разделу «Атомы, молекулы и ионы», чтобы лучше воспринимать суть изложенного материала в данной главе.

Содержание

- Основы строения атома

- Состав ядра атома

- Атомная единица массы

- Порядковый номер атома и атомная масса элемента

Основы строения атома

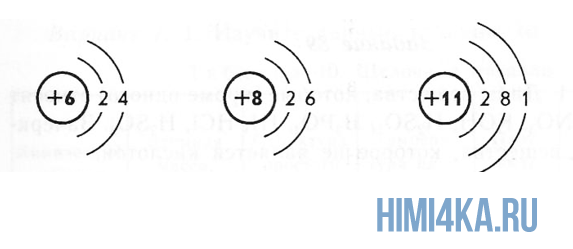

Пока не будем говорить, кто и когда узнал о существовании атома, а сразу перейдем к основам его строения: Атом — это мельчайшая частица вещества, которая состоит из ядра (заряд «+»), окруженного электронами (заряд «–»).

Электроны расположены на электронных оболочках атома: чем больше заряд ядра, тем больше электронов и электронных оболочек. Сам атом заряда не имеет, так как он является электрически нейтральным: заряд ядра (+) равен сумме зарядов электронов (-), вращающихся вокруг ядра.

Состав ядра атома

Ядро атома состоит из нуклонов. Нуклоны в ядре — это протоны и нейтроны. Массы протона и нейтрона почти одинаковые. Заряд ядра атома обозначается знаком «+» и зависит исключительно от количества протонов, ведь протоны — это носители положительного заряда, а нейтроны заряда не имеют никогда. Почти вся масса атома сконцентрирована в ядре, поэтому оно супер-тяжелое по отношению к остальному содержимому атома, однако, очень маленькое по сравнению с общим размером атома.

Чтобы вы понимали насколько оно мало, приведу пример: если атом увеличить до размеров Земли, то ядро атома будет в диаметре всего 60 метров. Надеюсь, что теперь у вас возникло некоторое представление об основах строения атома и составе атомного ядра.

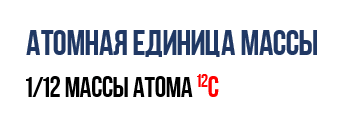

Атомная единица массы

Весы, которые могли бы взвесить атом, электрон или нуклон, пока еще не изобрели. Поэтому химики выражают массу частиц не в граммах, а в атомных единицах массы (а.е.м.). 1 атомная единица массы равна 1/12 массы атома углерода, ядро которого состоит из 6 протонов и 6 нейтронов. Получается, что масса 1 протона ~ 1 нейтрона ~ 1 а.е.м. Возникает вопрос, почему мы не считали 6 электронов, однако ответ будет простым: масса электрона ничтожно мала, поэтому в данном случае с ней даже не считаются.

Перевод граммов в атомные единицы массы выглядит так: 1 гр = 6,022×1023 а.е.м и наоборот 1 а.е.м. = 1,66×10-24 г. Число 6,022×1023 носит название — число Авогадро N (позже мы рассмотрим способ ее вычисления). Ниже изображена сравнительная таблица зарядов и масс элементарных частиц:

| Название | Заряд, Кл | Масса, гр | Масса, а.е.м. |

| Протон | +1,6·10-19 | 1,67·10-24 | 1,00728 |

| Нейтрон | 0 | 1,67·10-24 | 1,00866 |

| Электрон | -1,6·10-19 | 9,10·10-28 | 0,00055 |

Порядковый номер атома и атомная масса элемента

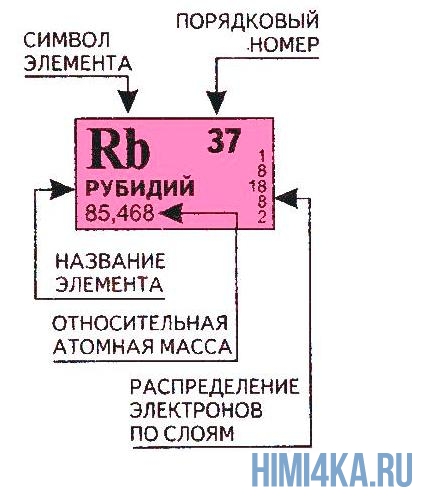

Переходим к двум фундаментальным понятиям. Порядковый (атомный) номер Z — это число протонов в ядре и оно же обозначает число электронов, потому как атом должен быть электрически нейтральным. Атомная масса элемента (относительная атомная масса, атомный вес) — это масса всех субатомных частиц (протонов, нейтронов, электронов) в атоме, выражается в а.е.м. Относительная атомная масса элемента один в один то же самое, что и атомная, но является безразмерной величиной и показывает, во сколько раз масса рассматриваемого атома превышает массу 1/12 части атома углерода. Порядковые номера и атомные массы химических элементов отмечены в таблице Менделеева.

Все атомы в природе с одинаковым порядковым номером в химическом отношении ведут себя практически одинаково и, поэтому их можно считать как атом одного и того же химического элемента. Каждый элемент обозначается одно- или двухбуквенным символом, заимствованный в большинстве случаев из греческого или латинского названия. Например, символ углерода — C, натрия — Na, азота — N и т.д. В качестве символа натрия Na, взяты две первые буквы его латинского названия натриум, чтобы отличить его от азота N (латинское название нитроген). В таблице Менделеева приведен алфавитный перечень элементов и их символов, их порядковый номер и атомные массы.

Надеюсь урок 1 «Схема строения атомов» был понятным и познавательным. Если у вас возникли вопросы, пишите их в комментарии.

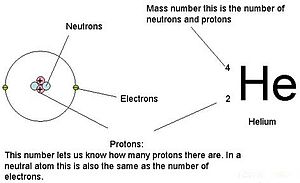

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

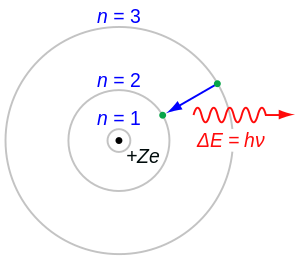

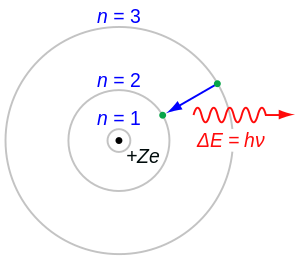

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

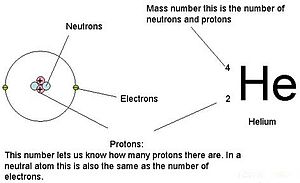

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

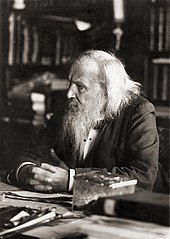

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

Главное отличие

Основное различие между атомной массой и атомным номером заключается в том, что атомная масса — это общее количество нейтронов и протонов в ядре атома, а атомный номер — это общее количество протонов, существующих в ядре атома.

Атомная масса против атомного номера

Общее количество нейтронов и протонов, которые существуют в ядре атома, объединяются, чтобы сделать массу атома известной как его атомная масса. Итак, атомная масса — это средний вес атома. С другой стороны, общее количество протонов, присутствующих в ядре атома, известное как атомный номер.

Атомная масса также распознается как атомный вес, тогда как атомная масса также распознается как число протона. Атомная масса обозначается буквой «А». С другой стороны, атомный номер обозначается буквой «Z». Атомная масса не используется для различения различных элементов. С другой стороны, атомный номер, используемый для идентификации и классификации различных элементов. Атомную массу элемента можно измерить с помощью атомной единицы массы (а.е.м.). С другой стороны, атомный номер — это число или цифра, которые можно использовать для фиксации элементов в периодической таблице.

Поскольку изотопы атома имеют одинаковое количество протонов, но разное количество нейтронов, атомная масса может использоваться для классификации различных изотопов элемента. С другой стороны, все изотопы элемента имеют одинаковый атомный номер, поэтому его нельзя использовать для их классификации. Например, атомная масса углерода составляет двенадцать и тринадцать для двух его изотопов. С другой стороны, его атомный номер равен шести для всех изотопов.

Сравнительная таблица

| Атомная масса | Атомный номер |

| Общее количество нейтронов и протонов, существующих в ядре, которые образуют массу атома, известно как атомная масса. | Общее количество протонов, существующих в ядре атома, называется атомным номером. |

| Также известный как | |

| Его также называют атомным весом. | Его также называют протонным числом. |

| Представление | |

| Он представлен как средний вес атома. | Он представляет собой количество нуклонов, т. Е. Протонов в ядре. |

| Обозначается как | |

| Буква «А» обозначает атомную массу. | Атомный номер, обозначенный буквой «Z». |

| Изотопы | |

| Изотопы атома имеют разную атомную массу. | Изотопы атома имеют одинаковый атомный номер. |

| Идентификация изотопов | |

| Атомная масса помогает идентифицировать разные изотопы. | Его нельзя использовать для идентификации различных изотопов атома. |

| Классификация элементов | |

| Атомная масса не используется для различения различных элементов. | Атомный номер используется для идентификации и классификации различных элементов. |

| Расчеты | |

| Атомную массу элемента можно измерить с помощью атомной единицы массы (а.е.м.). | Это число или цифра, которые можно использовать для фиксации элементов в периодической таблице. |

| Связь | |

| Это можно узнать, добавив количество нейтрона к атомному номеру. | Это можно узнать, вычтя количество нейтронов из атомной массы элемента. |

| Пример | |

| Атомная масса углерода составляет двенадцать и тринадцать для двух его изотопов. | Атомный номер атома углерода равен шести для всех изотопов. |

Что такое атомная масса ?

Атомная масса представлена как средний вес атома, а также считается атомной массой. Атом состоит из трех субатомных частиц, то есть протонов, нейтронов и электронов, так как электроны очень легкие по весу, поэтому атомная масса считается массой общего количества нейтронов и протонов, присутствующих в ядре атома.

Буква «А» обозначает атомную массу. Он выражается в форме единой атомной единицы массы или аму. Одна атомная единица массы равна 1/12 массы одного атома C12 или углерода-12 со значением 1,660 539 066 60 (50) × 10 −27 кг. Например, масса атома углерода-12 равнялась 12 а.е.м. Поскольку электроны очень легкие по весу, масса изотопа углерода-12 состоит из 6 нейтронов и 6 протонов. Протоны и нейтроны имеют одинаковую массу, поэтому было сказано, что они оба имеют массу, равную 1 u.

Поскольку разные изотопы атома различаются по количеству нейтронов. Итак, все они имеют разную атомную массу. Вот почему атомную массу можно использовать для идентификации различных изотопов элемента. Но он не используется для различения разных элементов. Атомную массу элемента также можно узнать, добавив номер нейтрона к его атомному номеру.

Что такое атомный номер ?

Атомный номер — это общее количество протонов, присутствующих в ядре атома. Его также называют протонным числом. Обозначается буквой «Z». Поскольку все изотопы элемента имеют одинаковое число протонов, атомный номер не может использоваться для различения изотопов этого элемента.

Атомный номер используется для идентификации и классификации различных элементов. Это число или цифра, которые можно использовать для фиксации элементов в периодической таблице. Различные элементы идентифицируются в соответствии с их конкретным атомным номером и в соответствии с ним помещаются в периодическую таблицу.

Например, атом с порядковым номером 12 является углеродом, так как в его ядре 12 протонов. Атом с другим атомным номером будет другим номером. В периодической таблице все элементы расположены в соответствии с их возрастающим атомным номером. Итак, самый верхний элемент, присутствующий в верхнем левом углу таблицы, — это водород с атомным номером 1. Следующим является гелий с атомным номером 2 и так далее.

Поскольку атомная масса — это количество протонов и нейтронов в ядре атома, атомный номер также можно узнать, вычитая количество нейтрона из атомной массы элемента.

Ключевые отличия

- Общее количество нейтронов и протонов, существующих в ядре атома, известно как атомная масса, тогда как общее количество протонов, присутствующих в ядре атома, известно как атомный номер.

- Атомная масса также признается атомной массой. С другой стороны, атомный номер также распознается как номер протона.

- Атомная масса представлена как средний вес атома. С другой стороны, атомный номер представляет собой общее количество нуклонов, то есть протонов в ядре.

- Атомная масса обозначается буквой «А». И наоборот, атомный номер обозначается буквой «Z».

- Изотопы атома имеют разную атомную массу. С другой стороны, изотопы атома имеют одинаковый атомный номер.

- Атомная масса помогает идентифицировать разные изотопы. С другой стороны, атомный номер не может использоваться для идентификации различных изотопов атома.

- Атомная масса не используется для различения различных элементов, в то время как атомный номер используется для идентификации и классификации различных элементов.

- Атомную массу элемента можно измерить с помощью атомной единицы массы (а.е.м.). С другой стороны, атомный номер — это число или цифра, которые можно использовать для фиксации элементов в периодической таблице.

- Атомную массу элемента можно узнать, добавив номер нейтрона к его атомному номеру, тогда как; атомный номер можно узнать, вычтя номер нейтрона из атомной массы элемента.

- Атомная масса углерода составляет двенадцать и тринадцать для двух его изотопов. С другой стороны, атомный номер атома углерода равен шести для всех изотопов.

Заключение

Вышеупомянутое обсуждение резюмирует, что атомная масса — это средний вес элемента, который равен количеству его протонов и нейтронов в ядре. С другой стороны, атомный номер — это количество протонов, присутствующих в ядре атома.

Вас смущают все числа в периодической таблице? Вот что они означают и где найти важные элементы.

Содержание

- Атомный номер элемента

- Атомная масса или атомная масса элемента

- Группа элементов

- Element Period

- Электронная конфигурация

- Другая информация о Периодической таблице

Атомный номер элемента

Один номер, который вы найдете на во всех периодических таблицах есть атомный номер для каждого элемента. Это количество протонов в элементе, которое определяет его идентичность.

Как его идентифицировать: Не существует ‘ • стандартный макет ячейки элемента, поэтому вам необходимо определить расположение каждого важного числа для конкретной таблицы. Атомный номер прост, потому что это целое число, которое увеличивается при перемещении слева направо по таблице. Самый низкий атомный номер – 1 (водород), а самый высокий атомный номер – 118.

Примеры: Атомный номер первого элемента, водорода, равно 1. Атомный номер меди равен 29.

Атомная масса или атомная масса элемента

Большинство периодических таблиц включают значение атомной массы (также называемой атомным весом) на плитке каждого элемента. Для одного атома элемента это будет целое число, сложив вместе количество протонов, нейтронов и электронов для атома. Однако значение, указанное в периодической таблице, представляет собой среднее значение массы всех изотопов данного элемента. Хотя количество электронов не дает значительного увеличения массы атома, изотопы имеют разное количество нейтронов, которые влияют на массу.

Как для определения: Атомная масса – десятичное число. Количество значащих цифр варьируется от таблицы к таблице. Обычно значения перечисляются с двумя или четырьмя десятичными знаками. Кроме того, атомная масса время от времени пересчитывается, поэтому это значение может незначительно изменяться для элементов в последней таблице по сравнению с более старой версией.

Примеры. Атомная масса водорода равна 1,01 или 1,0079. Атомная масса никеля составляет 58,69 или 58,6934.

Группа элементов

Многие периодические таблицы перечисляют номера групп элементов, которые являются столбцы периодической таблицы. Элементы в группе имеют одинаковое количество валентных электронов и, таким образом, имеют много общих химических и физических свойств. Однако не всегда существовал стандартный метод нумерации групп, поэтому это может сбивать с толку при просмотре старых таблиц.

Как идентифицировать Это: номер группы элементов указан над верхним элементом каждого столбца. Значения группы элементов представляют собой целые числа от 1 до 18.

Примеры: Водород принадлежит к группе элементов 1. Бериллий – это первый элемент в группе 2. Гелий – первый элемент в группе 18.

Element Period

Строки периодического таблицы называются периодами. В большинстве периодических таблиц их не нумеруют, потому что они довольно очевидны, но в некоторых таблицах они есть.. Период указывает на самый высокий уровень энергии, достигнутый электронами атома элемента в основном состоянии.

Как это идентифицировать: Номера периодов расположены в левой части таблицы. Это простые целые числа.

Примеры: Строка, начинающаяся с водорода, равна 1. Строка, начинающаяся с лития, равна 2 .

Электронная конфигурация

Некоторые периодические таблицы перечисляют электронную конфигурацию атома элемента, обычно записанную в сокращенном виде как экономить место. В большинстве таблиц это значение отсутствует, поскольку оно занимает много места.

Как это определить: Это не простое число, но включает орбитали.

Примеры: Электронная конфигурация для водорода равна 1s 1 .

Другая информация о Периодической таблице

Помимо чисел, в периодической таблице содержится и другая информация. Теперь, когда вы знаете, что означают числа, вы можете узнать, как прогнозировать периодичность свойств элемента и как использовать периодическую таблицу в расчетах.