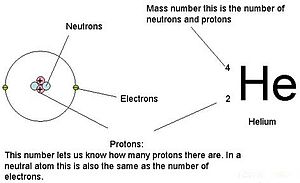

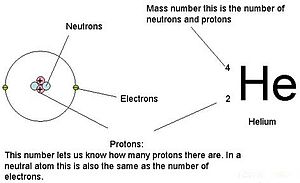

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

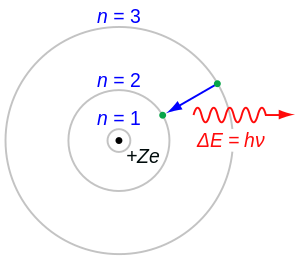

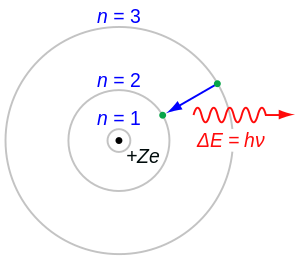

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

An explanation of the superscripts and subscripts seen in atomic number notation. Atomic number is the number of protons, and therefore also the total positive charge, in the atomic nucleus.

The Rutherford–Bohr model of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) or a hydrogen-like ion (Z > 1). In this model it is an essential feature that the photon energy (or frequency) of the electromagnetic radiation emitted (shown) when an electron jumps from one orbital to another be proportional to the mathematical square of atomic charge (Z2). Experimental measurement by Henry Moseley of this radiation for many elements (from Z = 13 to 92) showed the results as predicted by Bohr. Both the concept of atomic number and the Bohr model were thereby given scientific credence.

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom’s atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the «relative isotopic mass»), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element’s standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl ‘number’, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element’s numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight («Atomgewicht»).[1] However, in consideration of the elements’ observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom’s mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron’s charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom’s atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford’s estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford’s paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley’s 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek’s hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek’s and Bohr’s hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory’s postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley’s law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley’s work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley’s death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout’s hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or «protyles») of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout’s hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout’s law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two «nuclear electrons» (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element’s electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2023, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain «magic» numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0.

See also[edit]

- Atomic theory

- Chemical element

- Effective atomic number (disambiguation)

- Even and odd atomic nuclei

- Exotic atom

- History of the periodic table

- List of elements by atomic number

- Mass number

- Neutron number

- Neutron–proton ratio

- Prout’s hypothesis

References[edit]

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). «XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements». Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

Загрузить PDF

Загрузить PDF

Атомный номер элемента — это число протонов в ядре одного атома этого элемента. Атомный номер элемента или изотопа остается постоянным, поэтому с его помощью можно узнать другие величины, например, количество электронов и нейтронов в атоме.

-

1

Найдите периодическую систему химических элементов (таблицу Менделеева). Если хотите, воспользуйтесь таблицей в этой статье. У каждого элемента свой атомный номер, а элементы в таблице упорядочены по атомным номерам. Найдите таблицу Менделеева или просто запомните ее.

- Таблицу Менделеева можно найти в большинстве учебников по химии.

-

2

Найдите нужный элемент. В таблице приводится полное название элемента и его химический символ (например, Hg для ртути). Если у вас не получается найти элемент, в поисковой системе введите «химический символ <название элемента>».

-

3

Найдите атомный номер. Как правило, он находится в верхнем левом или верхнем правом углу ячейки элемента, но может быть и в другом месте. Атомный номер всегда выражен целым числом.

- Если вы видите десятичную дробь, это атомная масса.

-

4

Убедитесь, что нашли атомный номер. Элементы таблицы упорядочены по возрастанию атомных номеров. Если атомный номер нужного элемента равен «33», то атомный номер предыдущего элемента должен быть равен «32», а следующего элемента — «34». Если это так, вы нашли атомный номер.

- Иногда таблица выглядит так, что после бария (56) и радия (88) есть пустые ячейки. На самом деле они не пустые — соответствующие элементы расположены внизу таблицы. Это сделано для того, чтобы записать таблицу в определенной форме.

-

5

Запомните, что такое атомный номер. Атомный номер — это число протонов в ядре одного атома элемента.[1]

Это фундаментальная величина, характеризующая элемент. Количество протонов определяет общий электрический заряд ядра, который указывает на число электронов, вращающихся вокруг атома. Поскольку электроны участвуют почти во всех химических взаимодействиях, атомный номер косвенно устанавливает большинство физических и химических свойств элемента.- Другими словами, любой атом с восемью протонами является атомом кислорода. Два атома кислорода могут иметь разное количество нейтронов или электронов (если один из атомов является ионом), но у них всегда будет по восемь протонов.

Реклама

-

1

Выясните атомный вес. В таблице атомный вес находится под названием элемента и представляет собой десятичную дробь с двумя или тремя знаками после десятичной запятой. Атомный вес — это средняя масса одного атома элемента по отношению к массе элемента, который находится в природе. Атомный вес измеряется в «атомных единицах массы» (а.е.м.).

- В некоторых учебниках и статьях атомный вес называется «относительной атомной массой».[2]

- В некоторых учебниках и статьях атомный вес называется «относительной атомной массой».[2]

-

2

Округлите атомный вес, чтобы найти массовое число. Массовое число — это общее количество протонов и нейтронов в одном атоме элемента. Это число легко найти: посмотрите в таблице атомный вес и округлите его до ближайшего целого числа. [3]

- Этот метод работает, потому что атомный вес нейтронов и протонов приблизительно равен 1 а.е.м., а атомный вес электронов приблизительно равен 0 а.е.м. Атомный вес измеряется довольно точно, поэтому в нем присутствуют цифры после десятичной запятой, но нас интересует только целое число, которое позволит узнать количество протонов и нейтронов.

- Помните, что атомный вес представляет собой усредненное значение. Например, среднее массовое число брома равно 80, но, как оказалось, массовое число одного атома брома практически всегда равно 79 или 81.[4]

-

3

Найдите количество электронов. Атом состоит из одинакового количества протонов и электронов, поэтому число электронов равно числу протонов. Электроны заряжены отрицательно, поэтому они уравновешивают и нейтрализуют протоны, которые заряжены положительно.[5]

- Если атом теряет или приобретает электроны, он превращается в ион, то есть становится электрически заряженным атомом.

-

4

Найдите количество нейтронов. Так как атомный номер = количество протонов, а массовое число = количество протонов + количество нейтронов, то число нейтронов = массовое число — атомный номер. Вот пара примеров:

- Один атом гелия (He) имеет массовое число 4 и атомный номер 2. Поэтому в нем 4 — 2 = 2 нейтрона.

- Атом серебра (Ag) имеет среднее массовое число 108 (из таблицы Менделеева) и атомный номер 47. Поэтому в атоме серебра 108 — 47 = 61 нейтрон.

-

5

Запомните, что такое изотопы. Изотоп — это разновидность атома с определенным количеством нейтронов. Если в химической задаче упоминается «Бор-10» или 10B, речь идет об элементах бора с массовым числом 10.[6]

Используйте это массовое число вместо массового числа бора из таблицы Менделеева.- Атомный номер изотопов никогда не меняется. Изотоп элемента имеет такое же количество протонов, как и сам элемент.

Реклама

Советы

- Атомный вес тяжелых элементов приводится в скобках. Это означает, что атомный вес вычислен на основе наиболее стабильного изотопа, а не среднего числа нескольких изотопов.[7]

(Это не влияет на атомный номер элемента.)

Реклама

Об этой статье

Эту страницу просматривали 14 310 раз.

Была ли эта статья полезной?

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР

- АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР (обозначение Z), число протонов в ядре атома элемента, равное числу электронов, движущихся вокруг этого ядра. Атомный номер ставят в виде нижнего индекса перед символом элемента; например, атомный номер углерода записывается как 6С. Атомный номер определяет химические свойства элемента и его положение в периодической таблице. У всех изотопов элемента один и тот же атомный номер, но разные атомные массы, поскольку число нейтронов у них различно.

Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь.

Смотреть что такое «АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР» в других словарях:

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — (порядковый номер) Z, номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре и определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — (порядковый номер) номер элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в ат. ядре. Определяет химические и большинство физических св в атома. Физический энциклопедический словарь. М.: Советская энциклопедия. Главный редактор А … Физическая энциклопедия

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР, порядковый номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома … Современная энциклопедия

-

Атомный номер — Atomic number номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов; равен числу протонов в атомном ядре. Термины атомной энергетики. Концерн Росэнергоатом, 2010 … Термины атомной энергетики

-

Атомный номер — АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР, порядковый номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома. … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР — порядковый номер хим. элемента в Периодической системе элементов (см.). А н. равен числу протонов в атомном ядре, которое, в свою очередь, равно числу электронов (см.). А. н. определяет хим. и большинство физ. свойств атома … Большая политехническая энциклопедия

-

атомный номер — — [Я.Н.Лугинский, М.С.Фези Жилинская, Ю.С.Кабиров. Англо русский словарь по электротехнике и электроэнергетике, Москва, 1999 г.] Тематики электротехника, основные понятия EN atomic number … Справочник технического переводчика

-

атомный номер — порядковый номер, Z, номер химического элемента в периодической системе элементов. Равен числу протонов в атомном ядре и определяет химические и большинство физических свойств атома. * * * АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР АТОМНЫЙ НОМЕР (порядковый номер), Z, номер… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

атомный номер — atominis skaičius statusas T sritis Standartizacija ir metrologija apibrėžtis Cheminio elemento eilės numeris periodinėje elementų sistemoje. Apibūdina atomo branduolio protonų skaičių, taip pat atitinkamo neutraliojo atomo elektronų skaičių.… … Penkiakalbis aiškinamasis metrologijos terminų žodynas

-

атомный номер — atominis skaičius statusas T sritis Standartizacija ir metrologija apibrėžtis Protonų skaičius atomo branduolyje. atitikmenys: angl. atomic number; charge number; ordinal number; proton number vok. Atomnummer, f; Atomzahl, f; Kernladungszahl, f;… … Penkiakalbis aiškinamasis metrologijos terminų žodynas

Заря́довое число́атомного ядра (b) (синонимы: а́томный но́мер, а́томное число́, поря́дковый но́мерхимического элемента (b) ) — количество протонов (b) в атомном ядре. Зарядовое число равно заряду ядра в единицах элементарного заряда (b) и одновременно равно порядковому номеру соответствующего ядра химического элемента в таблице Менделеева (b) . Обычно обозначается буквой Z[⇨].

Термин «атомный» или «порядковый» номер обычно используется в атомной физике (b) и в химии (b) , тогда как эквивалентный термин «зарядовое число» — в ядерной физике (b) . В неионизированном (b) атоме количество электронов (b) в электронных оболочках (b) совпадает с зарядовым числом.

Ядра с одинаковым зарядовым числом, но различным массовым числом (b) A (которое равно сумме числа протонов Z и числа нейтронов N) являются различными изотопами (b) одного и того же химического элемента, поскольку именно заряд ядра определяет структуру электронной оболочки атома и, следовательно, его химические свойства. Более трёх четвертей химических элементов существует в природе в виде смеси изотопов (см. Моноизотопный элемент (b) ), и средняя изотопная масса изотопной смеси элемента (называемая относительной атомной массой (b) ) в определённой среде на Земле определяет стандартную атомную массу (b) элемента (ранее использовалось название «атомный вес»). Исторически именно эти атомные веса элементов (по сравнению с водородом) были величинами, которые измеряли химики в XIX веке.

Поскольку протоны и нейтроны имеют приблизительно одинаковую массу (масса электронов (b) пренебрежимо мала по сравнению с их массой), а дефект массы (b) нуклонного связывания всегда мал по сравнению с массой нуклона, значение атомной массы любого атома, выраженной в атомных единицах массы (b) , находится в пределах 1 % от целого числа А.

История

Периодическая таблица и порядковые номера для каждого элемента

Поиски основы естественной классификации и систематизации химических элементов, основанной на связи их физических и химических свойств с атомным весом, предпринимались на протяжении длительного времени. В 1860-х годах появился ряд работ, связывающих эти характеристики — спираль Шанкуртуа (b) , таблица Ньюлендса (b) , таблицы Одлинга (b) и Мейера (b) , но ни одна из них не давала однозначного исчерпывающего описания закономерности. Сделать это удалось русскому химику Д. И. Менделееву (b) . 6 марта 1869 года (18 марта (b) 1869 года (b) ) на заседании Русского химического общества (b) было зачитано сообщение Менделеева об открытии им Периодического закона химических элементов (b) [1], а вскоре его статья «Соотношение свойств с атомным весом элементов» была опубликована в «Журнале Русского физико-химического общества (b) »[2]. В том же году вышло первое издание учебника Менделеева «Основы химии», где была приведена его периодическая таблица. В статье, датированной 29 ноября 1870 года (11 декабря (b) 1870 года (b) ), опубликованной в «Журнале Русского химического общества» под названием «Естественная система элементов и применение её к указанию свойств неоткрытых элементов», Менделеев впервые употребил термин «периодический закон» и указал на существование нескольких не открытых ещё элементов[3].

В своих работах Менделеев расположил элементы в порядке их атомных весов, но при этом сознательно допустил отклонение от этого правила, поместив теллур (b) (атомный вес 127,6) впереди иода (b) (атомный вес 126,9)[4], объясняя это химическими свойствами элементов. Такое размещение элементов правомерно с учётом их зарядового числа Z, которое было неизвестно Менделееву. Последующее развитие атомной химии подтвердило правильность догадки учёного.

Модели атома Резерфорда-Бора и Ван ден Брука

В 1911 году британский физик Эрнест Резерфорд (b) предложил модель атома (b) , согласно которой в центре атома расположено ядро, содержащее б́ольшую часть массы атома и положительный заряд, который в единицах заряда электрона должен был быть равен примерно половине атомного веса атома, выраженного в числе атомов водорода. Резерфорд сформулировал свою модель на основе данных об атоме золота (b) (Z = 79, A = 197), и, таким образом, получалось, что у золота должен быть заряд ядра около 100 (в то время как порядковый номер золота в периодической таблице 79). Через месяц после выхода статьи Резерфорда голландский физик-любитель Антониус ван ден Брук (b) впервые предположил, что заряд ядра и число электронов в атоме должны быть точно равны его порядковому номеру в периодической таблице (он же — атомный номер, обозначаемый Z). Эта гипотеза в конечном счёте подтвердилась.

Но с точки зрения классической электродинамики, в модели Резерфорда электрон, двигаясь вокруг ядра, должен был бы излучать (b) энергию непрерывно и очень быстро и, потеряв её, упасть на ядро. Чтобы разрешить эту проблему, в 1913 году датский физик Нильс Бор (b) предложил свою модель (b) атома. Бор ввёл допущение, что электроны в атоме могут двигаться только по определённым (стационарным) орбитам, находясь на которых, они не излучают энергию, а излучение или поглощение происходит только в момент перехода с одной орбиты на другую. При этом стационарными являются лишь те орбиты, при движении по которым момент количества движения (b) электрона равен целому числу постоянных Планка (b) [5]: .

Эксперименты Мозли 1913 года и «пропавшие» химические элементы

В 1913 году британский химик Генри Мозли (b) после дискуссии с Н.Бором решил проверить гипотезы Ван ден Брука и Бора на эксперименте[6]. Для этого Мозли измерил длины волн спектральных линий (b) фотонных переходов (линии K и L) в атомах алюминия (Z = 13) и золота (Z = 79), использовавшихся в качестве серии мишеней внутри рентгеновской трубки (b) [7]. Квадратный корень частоты этих фотонов (рентгеновских лучей) увеличивался от одной цели к другой в арифметической прогрессии. Это привело Мозли к заключению (закон Мозли (b) ), что значение атомного номера почти соответствует (в работе Мозли — со смещением на одну единицу для K-линий) вычисленному электрическому заряду ядра, то есть величине Z. Среди прочего эксперименты Мозли продемонстрировали, что ряд лантаноидов (b) (от лантана (b) до лютеция (b) включительно) должен содержать ровно 15 элементов — не меньше и не больше, что было далеко не очевидно для химиков того времени.

После смерти Мозли в 1915 году его методом были исследованы атомные номера всех известных элементов от водорода до урана (b) (Z = 92). Было обнаружено, что в периодической таблице отсутствуют семь химических элементов (с Z < 92), которые были идентифицированы как ещё не открытые, с атомными номерами 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 и 91[8]. Все эти семь «пропавших» элементов были обнаружены в период с 1918 по 1947 год: технеций (b) (Z = 43), прометий (b) (Z = 61), гафний (b) (Z = 72), рений (b) (Z = 75), астат (b) (Z = 85), франций (b) (Z = 87) и протактиний (b) (Z = 91)[8]. К этому времени также были обнаружены первые четыре трансурановых элемента (b) , поэтому периодическая таблица была заполнена без пробелов до кюрия (b) (Z = 96).

Протон и гипотеза «ядерных электронов»

К 1915 году в научном сообществе сложилось понимание того факта, что зарядовые числа Z, они же — порядковые номера элементов, должны быть кратны величине заряда ядра атома водорода, но не было объяснения причин этого. Сформулированная ещё в 1816 году гипотеза Праута (b) предполагала, что водород является некоей первичной материей, из которой путём своего рода конденсации образовались атомы всех других элементов и, следовательно, атомные веса всех элементов, равно как и заряды их ядер, должны измеряться целыми числами. Но в 1907 году опыты Резерфорда и Ройдса (b) [en] показали, что альфа-частицы (b) с зарядом +2 являются ядрами атомов гелия, масса которых превышает массу водорода в четыре, а не в два раза. Если гипотеза Праута верна, то что-то должно было нейтрализовать заряды ядер водорода, присутствующие в ядрах более тяжёлых атомов.

В 1917 году (в экспериментах, результаты которых были опубликованы в 1919 и 1925 годах), Резерфорд доказал, что ядро водорода присутствует в других ядрах; этот результат обычно интерпретируют как открытие протонов (b) [9]. Эти эксперименты начались после того, как Резерфорд заметил, что, когда альфа-частицы были выброшены в воздух (в основном состоящий из азота), детекторы зафиксировали следы типичных ядер водорода. После экспериментов Резерфорд проследил реакцию на азот в воздухе и обнаружил, что когда альфа-частицы вводятся в чистый газообразный азот, эффект оказывается больше. В 1919 году Резерфорд предположил, что альфа-частица выбила протон из азота, превратив его в углерод (b) . После наблюдения изображений камеры Блэкетта в 1925 году Резерфорд понял, что произошло обратное: после захвата альфа-частицы протон выбрасывается, поэтому тяжёлый кислород (b) , а не углерод, является конечным результатом, то есть Z не уменьшается, а увеличивается. Это была первая описанная ядерная реакция (b) : 14N + α → 17O + p.

Резерфорд назвал новые тяжёлые ядерные частицы протонами в 1920 году (предлагались альтернативные названия — «прутоны» и «протилы»). Из работ Мозли следовало, что ядра тяжёлых атомов имеют более чем вдвое большую массу, чем можно было бы ожидать при условии, что они состоят только из ядер водорода, и поэтому требовалось объяснение для «нейтрализации» предполагаемых дополнительных протонов, присутствующих во всех тяжелых ядрах. В связи с этим была выдвинута гипотеза о так называемых «ядерных электронах». Так, предполагалось, что ядро гелия состоит из четырёх протонов и двух «ядерных электронов», нейтрализующих заряд двух протонов. В случае золота с атомной массой 197 и зарядом 79, ранее рассмотренном Резерфордом, предполагалось, что ядро атома золота содержит 118 этих «ядерных электронов».

Открытие нейтрона и его значение

Несостоятельность гипотезы «ядерных электронов» стала очевидной после открытия нейтрона (b) [en]Джеймсом Чедвиком (b) в 1932 году[10]. Наличие нейтронов (b) в ядрах атомов легко объясняло расхождение между атомным весом и зарядным числом атома: так, в атоме золота содержится 118 нейтронов, а не 118 ядерных электронов, а положительный заряд ядра полностью состоит из 79 протонов. Таким образом, после 1932 года атомный номер элемента Z стал рассматриваться как число протонов в его ядре.

Символ Z

Зарядовое число обычно обозначается буквой Z, от нем. (b) atomzahl — «атомное число», «атомный номер»[11] Условный символ Z, вероятно, происходит от немецкого слова Atomzahl (атомный номер)[12], обозначающего число, которое ранее просто обозначало порядковое место элемента в периодической таблице и которое приблизительно (но не точно) соответствовало порядку элементов по возрастанию их атомных весов. Только после 1915 года, когда было доказано, что число Z является также величиной заряда ядра и физической характеристикой атома, немецкое слово Atomzahl (и его английский эквивалент англ. (b) Atomic number) стали широко использоваться в этом контексте.

Химические свойства

Каждый элемент обладает определённым набором химических свойств как следствие количества электронов, присутствующих в нейтральном атоме, которое представляет собой Z (атомный номер). Конфигурация электронов (b) в атоме следует из принципов квантовой механики (b) . Количество электронов в электронных оболочках каждого элемента, особенно в самой внешней валентной оболочке (b) , является основным фактором, определяющим его химические связи. Следовательно, только атомный номер определяет химические свойства элемента, и именно поэтому элемент может быть определён как состоящий из любой смеси атомов с данным атомным номером.

Новые элементы

При поиске новых элементов исследователи руководствуются представлениями об зарядовых числах этих элементов. По состоянию на конец 2019 года были обнаружены все элементы с зарядовыми числами от 1 до 118. Синтез новых элементов осуществляется путем бомбардировки атомов-мишеней тяжёлых элементов ионами таким образом, что сумма зарядовых чисел атома-мишени и иона-«снаряда» равна зарядовому числу создаваемого элемента. Как правило, период полураспада (b) элемента становится короче с увеличением атомного номера, хотя для неизученных изотопов с определённым числом протонов и нейтронов могут существовать так называемые «острова стабильности (b) »[13].

См. также

- Атомная теория (b)

- Гипотеза Праута (b)

- Химический элемент (b)

- Периодическая таблица химических элементов (b)

- Список химических элементов (b)

Примечания

- ↑ Трифонов Д. Н. Несостоявшееся выступление Менделеева (6 (18) марта 1869 г.)Архивная копия от 18 марта 2014 на Wayback Machine (b) // Химия, № 04 (699), 16-28.02.2006

- ↑ Менделеев Д. И. Соотношение свойств с атомным весом элементов // Журнал Русского химического общества. — 1869. — Т. I. — С. 60—77. Архивировано 18 марта 2014 года.

- ↑ Менделеев Д. И. Естественная система элементов и применение её к указанию свойств неоткрытых элементов // Журнал Русского химического общества (b) . — 1871. — Т. III. — С. 25—56. Архивировано 17 марта 2014 года.

- ↑ Периодический закон химических элементов // Энциклопедический словарь (b) юного химика. 2-е изд. / Сост. В. А. Крицман, В. В. Станцо. — М.: Педагогика (b) , 1990. — С. 185. — ISBN 5-7155-0292-6.

- ↑ Планетарная модель атома. Постулаты БораАрхивная копия от 21 февраля 2009 на Wayback Machine (b) на Портале Естественных НаукАрхивная копия от 26 ноября 2009 на Wayback Machine (b)

- ↑ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic TableАрхивная копия от 4 марта 2016 на Wayback Machine (b) , Royal Chemical Society

- ↑ Moseley H. G. J. (b) XCIII. The high-frequency spectra of the elements (англ.) // Philosophical Magazine (b) , Series 6. — 1913. — Vol. 26, no. 156. — P. 1024. — doi (b) :10.1080/14786441308635052. Архивировано 22 января 2010 года.

- 1 2 Scerri E. A tale of seven elements (англ.). — Oxford University Press, 2013. — P. 47. — ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2.

- ↑ Petrucci R. H., Harwood W. S., Herring F. G. General Chemistry (англ.). — 8th ed.. — Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2002. — P. 41.

- ↑ Chadwick J. Existence of a Neutron (англ.) // Proceedings of the Royal Society A. — 1932. — Vol. 136, no. 830. — P. 692—708. — doi (b) :10.1098/rspa.1932.0112. — Bibcode (b) : 1932RSPSA.136..692C.

- ↑ General Chemistry Online: FAQ: Atoms, elements, and ions: Why is atomic number called «Z»? Why is mass number called «A»?. antoine.frostburg.edu. Дата обращения: 8 марта 2019. Архивировано 16 января 2000 года.

- ↑ Origin of symbol ZАрхивная копия от 16 января 2000 на Wayback Machine (b) . frostburg.edu

- ↑ Остров Стабильности за пределами таблицы Менделеева. Дата обращения: 29 ноября 2019. Архивировано 21 ноября 2018 года.