| Antonio Meucci | |

|---|---|

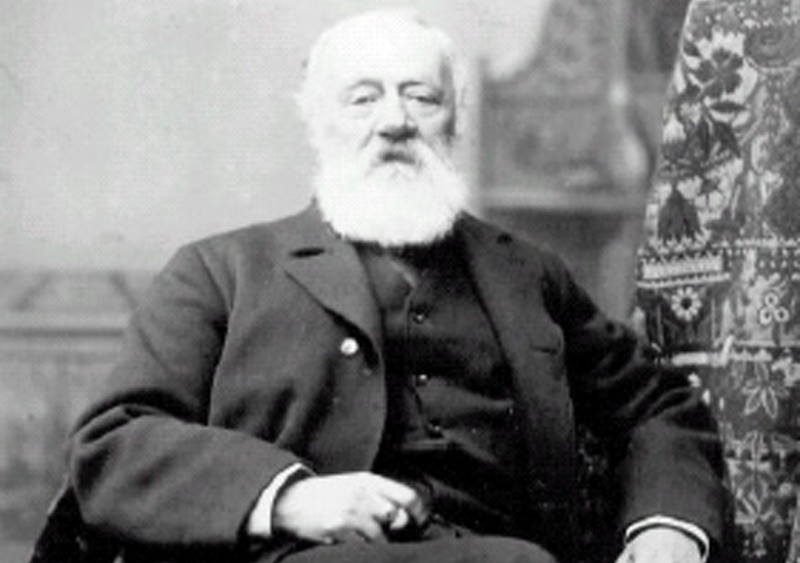

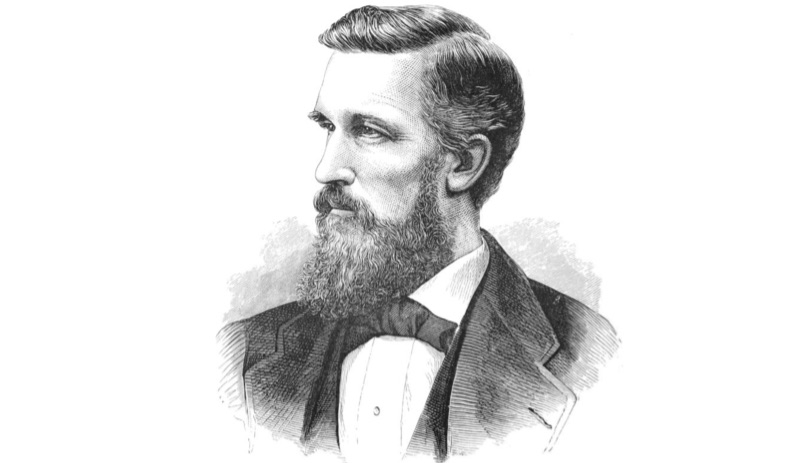

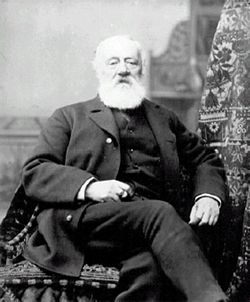

Meucci in 1878 | |

| Born | 13 April 1808 Florence, First French Empire (present-day Italy) |

| Died | 18 October 1889 (aged 81) Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Accademia di Belle Arti |

| Known for | Inventing a telephone-like device, innovator, businessman, supporter of Italian unification |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Communication devices, manufacturing, chemical and mechanical engineering, chemical and food patents |

Antonio Santi Giuseppe Meucci ( may-OO-chee,[1] Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo meˈuttʃi]; 13 April 1808 – 18 October 1889) was an Italian inventor and an associate of Giuseppe Garibaldi, a major political figure in the history of Italy.[2][3] Meucci is best known for developing a voice-communication apparatus that several sources credit as the first telephone.[4][5]

Meucci set up a form of voice-communication link in his Staten Island, New York, home that connected the second-floor bedroom to his laboratory.[6] He submitted a patent caveat for his telephonic device to the U.S. Patent Office in 1871, but there was no mention of electromagnetic transmission of vocal sound in his caveat. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was granted a patent for the electromagnetic transmission of vocal sound by undulatory electric current.[6] Despite the longstanding general crediting of Bell with the accomplishment, the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities supported celebrations of Meucci’s 200th birthday in 2008 using the title «Inventore del telefono» (Inventor of the telephone).[7] The U.S. House of Representatives in a resolution in 2002 also acknowledged Meucci’s work in the invention of the telephone,[8] although the U.S. Senate did not join the resolution and the interpretation of the resolution is disputed.

Early life[edit]

Meucci was born at Via dei Serragli 44 in the San Frediano borough of Florence, First French Empire (now in the Italian Republic), on 13 April 1808, as the first of nine children to Amatis Meucci and Domenica Pepi.[6] Amatis was at times a government clerk and a member of the local police, and Domenica was principally a homemaker. Four of Meucci’s siblings did not survive childhood.[9]

In November 1821, at the age of 13, he was admitted to Florence Academy of Fine Arts as its youngest student, where he studied chemical and mechanical engineering.[6] He ceased full-time studies two years later due to insufficient funds, but continued studying part-time after obtaining employment as an assistant gatekeeper and customs official for the Florentine government.[6]

In May 1825, because of the celebrations for the childbirth of Marie Anna of Saxony, wife of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Meucci conceived a powerful propellant mixture for flares. Unfortunately the fireworks went out of his control, causing damages and injuries in the celebration’s square. Meucci was arrested and suspected of conspiracy against the Grand Duchy.[10]

Meucci later became employed at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence as a stage technician, assisting Artemio Canovetti.[11]

In 1834 Meucci constructed a type of acoustic telephone to communicate between the stage and control room at the Teatro of Pergola. This telephone was constructed on the principles of pipe-telephones used on ships and still functions. He married costume designer Esterre Mochi, who was employed in the same theatre, on 7 August 1834.[6]

Havana, Cuba[edit]

In October 1835, Meucci and his wife emigrated to Cuba, then a Spanish province, where Meucci accepted a job at what was then called the Teatro Tacón in Havana (at the time, the greatest theater in the Americas). In Havana he constructed a system for water purification and reconstructed the Gran Teatro.[11][6]

In 1848 his contract with the governor expired. Meucci was asked by a friend’s doctors to work on Franz Anton Mesmer’s therapy system on patients with rheumatism. In 1849, he developed a popular method of using electric shocks to treat illness and subsequently experimentally developed a device through which one could hear inarticulate human voice. He called this device «telegrafo parlante» (talking telegraph).[12]

In 1850, the third renewal of Meucci’s contract with Don Francisco Martí y Torrens expired, and his friendship with General Giuseppe Garibaldi made him a suspect citizen in Cuba. On the other hand, the fame reached by Samuel F. B. Morse in the United States encouraged Meucci to make his living through inventions.[6]

Staten Island, New York[edit]

On 13 April 1850, Meucci and his wife emigrated to the United States, taking with them approximately 26,000 pesos fuertes in savings (approximately $500,000 in 2010 dollars), and settled in the Clifton area of Staten Island, New York, New York.[6]

The Meuccis would live there for the remainder of their lives. On Staten Island he helped several countrymen committed to the Italian unification movement and who had escaped political persecution. Meucci invested the substantial capital he had earned in Cuba into a tallow candle factory (the first of this kind in America) employing several Italian exiles. For two years Meucci hosted friends at his cottage, including General Giuseppe Garibaldi, and Colonel Paolo Bovi Campeggi, who arrived in New York two months after Meucci. They worked in Meucci’s factory.[citation needed]

In 1854, Meucci’s wife Esterre became an invalid due to rheumatoid arthritis.[citation needed] Meucci continued his experiments.

Electromagnetic telephone[edit]

Meucci studied the principles of electromagnetic voice transmission for many years[citation needed] and was able to transmit his voice through wires in 1856. He installed a telephone-like device within his house in order to communicate with his wife, who was ill at the time.[6] Some of Meucci’s notes written in 1857 describe the basic principle of electromagnetic voice transmission or in other words, the telephone:

Consiste in un diaframma vibrante e in un magnete elettrizzato da un filo a spirale che lo avvolge. Vibrando, il diaframma altera la corrente del magnete. Queste alterazioni di corrente, trasmesse all’altro capo del filo, imprimono analoghe vibrazioni al diaframma ricevente e riproducono la parola.

Translated:

It consists of a vibrating diaphragm and a magnet electrified by a spiral wire that wraps around it. The vibrating diaphragm alters the current of the magnet. These alterations of current, transmitted to the other end of the wire, create analogous vibrations of the receiving diaphragm and reproduce the word.

Meucci devised an electromagnetic telephone as a way of connecting his second-floor bedroom to his basement laboratory, and thus being able to communicate with his wife.[13] Between 1856 and 1870, Meucci developed more than 30 different kinds of telephones on the basis of this prototype.

A postage stamp was produced in Italy in 2003 that featured a portrait of Meucci.[14]

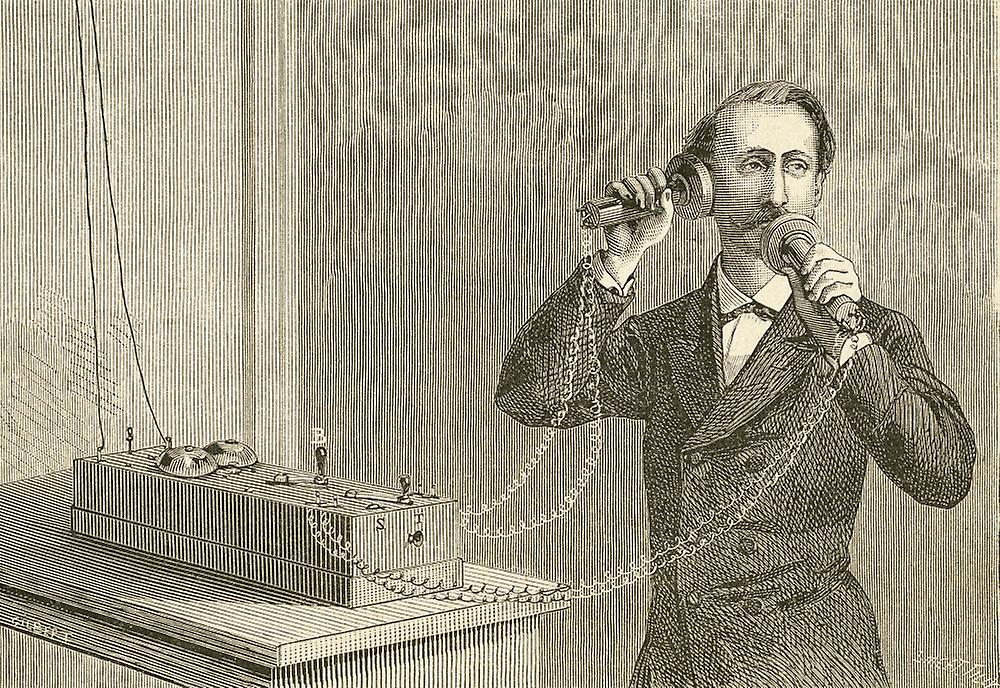

Around 1858, artist Nestore Corradi sketched Meucci’s communication concept. His drawing was used to accompany the stamp in a commemorative publication of the Italian Postal and Telegraph Society.[14]

Meucci intended to develop his prototype but did not have the financial means to keep his company afloat in order to finance his invention. His candle factory went bankrupt and Meucci was forced to unsuccessfully seek funds from rich Italian families. In 1860, he asked his friend Enrico Bandelari to look for Italian capitalists willing to finance his project. However, military expeditions led by Garibaldi in Italy had made the political situation in that country too unstable for anybody to invest.[11]

Bankruptcy[edit]

At the same time, Meucci was led to poverty by some fraudulent debtors. On 13 November 1861 his cottage was auctioned. The purchaser allowed the Meuccis to live in the cottage without paying rent, but Meucci’s private finances dwindled and he soon had to live on public funds and by depending on his friends. As mentioned in William J. Wallace’s ruling,[15] during the years 1859–1861, Meucci was in close business and social relations with William E. Ryder, who invested money in Meucci’s inventions and paid the expenses of his experiments. Their close working friendship continued until 1867.[citation needed]

In August 1870, Meucci reportedly was able to capture a transmission of articulated human voice at the distance of a mile by using a copper plate as a conductor, insulated by cotton. He called this device the «telettrofono». While he was recovering from injuries that befell him in a boiler explosion aboard a Staten Island ferry, the Westfield, Meucci’s financial and health state was so bad that his wife sold his drawings and devices to a second-hand dealer to raise money.[citation needed]

Patent caveat[edit]

On 12 December 1871 Meucci set up an agreement with Angelo Zilio Grandi (Secretary of the Italian Consulate in New York), Angelo Antonio Tremeschin (entrepreneur), Sereno G.P. Breguglia Tremeschin (businessman), in order to constitute the Telettrofono Company. The constitution was notarized by Angelo Bertolino, a Notary Public of New York. Although their society funded him with $20, only $15 was needed to file for a full patent application.[16][17] The caveat his lawyer submitted to the US Patent Office on 28 December 1871 was numbered 3335 and titled «Sound Telegraph».

The following is the text of Meucci’s caveat, omitting legal details of the Petition, Oath, and Jurat:[18]

CAVEAT

The petition of Antonio Meucci, of Clifton, in the County of Richmond and State of New York, respectfully represents:

That he has made certain improvements in Sound Telegraphs, …

The following is a description of the invention, sufficiently in detail for the purposes of this caveat.

I employ the well-known conducting effect of continuous metallic conductors as a medium for sound, and increases the effect by electrically insulating both the conductor and the parties who are communicating. It forms a Speaking Telegraph, without the necessity for any hollow tube.

I claim that a portion or the whole of the effect may also be realized by a corresponding arrangement with a metallic tube. I believe that some metals will serve better than others, but propose to try all kinds of metals.

The system on which I propose to operate and calculate consists in isolating two persons, separated at considerable distance from each other, by placing them upon glass insulators; employing glass, for example, at the foot of the chair or bench on which each sits, and putting them in communication by means of a telegraph wire.

I believe it preferable to have the wire of larger area than that ordinarily employed in the electric telegraph, but will experiment on this. Each of these persons holds to his mouth an instrument analogous to a speaking trumpet, in which the word may easily be pronounced, and the sound concentrated upon the wire. Another instrument is also applied to the ears, in order to receive the voice of the opposite party.

All these, to wit, the mouth utensil and the ear instruments, communicate to the wire at a short distance from the persons. The ear utensils being of a convex form, like a clock glass, enclose the whole exterior part of the ear, and make it easy and comfortable for the operator. The object is to bring distinctly to the hearing the word of the person at the opposite end of the telegraph.

To call attention, the party at the other end of the line may be warned by an electric telegraph signal, or a series of them. The apparatus for this purpose, and the skill in operating it, need be much less than for the ordinary telegraphing.

When my sound telegraph is in operation, the parties should remain alone in their respective rooms, and every practicable precaution should be taken to have the surroundings perfectly quiet. The closed mouth utensil or trumpet, and the enclosing the persons also in a room alone, both tend to prevent undue publicity to the communication.

I think it will be easy, by these means, to prevent the communication being understood by any but the proper persons.

It may be found practicable to work with the person sending the message insulated, and with the person receiving it, in the free electrical communication with the ground. Or these conditions may possibly be reversed and still operate with some success.

Both the conductors or utensils for mouth and ears should be, in fact I must say must be, metallic, and be so conditioned as to be good conductors of electricity.

I claim as my invention, and desire to have considered as such, for all the purposes of this Caveat,

The new invention herein set forth in all its details, combinations, and sub-combinations.

And more especially, I claim

First. A continuous sound conductor electrically insulated.

Second. The same adapted for telegraphing by sound or for conversation between distant parties electrically insulated.

Third. The employment of a sound conductor, which is also an electrical conductor, as a means of communication by sound between distant points.

Fourth. The same in combination with provisions for electrically insulating the sending and receiving parties.

Fifth. The mouthpiece or speaking utensil in combination with an electrically insulating conductor.

Sixth. The ear utensils or receiving vessels adapted to apply upon the ears in combination with an electrically insulating sound conductor.

Seventh. The entire system, comprising the electrical and sound conductor, insulated and furnished with a mouthpiece and ear pieces at each end, adapted to serve as specified.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand in presence of two subscribing witnesses.

ANTONIO MEUCCI

Witnesses:

Shirley McAndrew.

Fred’k Harper.

Endorsed:

Patent Office

Dec. 28, 1871

Analysis of Meucci’s caveat[edit]

Meucci repeatedly focused on insulating the electrical conductor and even insulating the people communicating, but does not explain why this would be desirable.[19] The mouth piece is like a «speaking trumpet» so that «the sound concentrated upon the wire» is communicated to the other person, but he does not say that the sound is converted to variable electrical conduction in the wire.[20] «Another instrument is also applied to the ears», but he does not say that variable electrical conduction in the wire is to be converted to sound.[20] In the third claim, he claims «a sound conductor which is also an electrical conductor, as a means of communication by sound»,[21] which is consistent with acoustic sound vibrations in the wire that get transmitted better if electrical conductors such as a wire or metallic tube are used.[22]

Meucci emphasizes that the conductors «for mouth and ears … must be metallic», but does not explain why this would be desirable.[23] He mentions «communication with the ground»[24] but does not suggest that a ground return must complete a circuit if only «the wire» (singular, not plural) is used between the sender’s mouth piece and the receiver’s ear piece, with one or the other person being electrically insulated from the ground by means of glass insulators («… consists in isolating two persons … by placing them upon glass insulators; employing glass, for example, at the foot of the chair or bench on which each sits, and putting them in communication by means of a telegraph wire»).[25]

Robert V. Bruce, a biographer of Bell, asserted that Meucci’s caveat could never have become a patent because it never described an electric telephone.[26][27]

Conflicting opinions of Meucci biographers[edit]

According to Bruce, Meucci’s own testimony as presented by Schiavo demonstrates that the Italian inventor «did not understand the basic principles of the telephone, either before or several years after Bell patented it.»[27]

Other researchers[who?] have pointed to inconsistencies and inaccuracies in Bruce’s account of the invention of the telephone, firstly with the name used by Meucci to describe his invention—Bruce refers to Meucci’s device as a «telephone», not as the «telettrofono». Bruce’s reporting of Meucci’s purported relationship with Dr. Seth R. Beckwith has been deemed inaccurate. Beckwith, a former surgeon and general manager of the Overland Telephone Company of New York, «had acquired a substantial knowledge in the telephonic field and had become an admirer of Meucci».[28] In 1885, he became general manager of the Globe Telephone Company, which had «started an action attempting to involve the government in hindering U.S. Bell’s monopoly.»[28] However, Meucci and his legal representative had cautioned Beckwith against misusing Meucci’s name for financial gain after Beckwith founded a company in New Jersey named the Meucci Telephone Company.[29][30][31]

Not only did Beckwith’s Globe Telephone Company base its claims against the Bell Telephone Company on Meucci’s caveat, but the claims were also supported by approximately 30 affidavits, which stated that Meucci had repeatedly built and used different types of electric telephones several years before Bell did.[32][33]

English historian William Aitken does not share Bruce’s viewpoint. Bruce indirectly referred to Meucci as «the silliest and weakest impostor»,[34] while Aitken has gone so far as to define Meucci as the first creator of an electrical telephone.[35]

Other recognition of Meucci’s work in the past came from the International Telecommunication Union, positing that Meucci’s work was one of the four precursors to Bell’s telephone,[citation needed] as well as from the Smithsonian Institution, which listed Meucci as one of the eight most important inventors of the telephone in a 1976 exhibit.[36]

Meucci and his business partners hired an attorney (J. D. Stetson), who filed a caveat on behalf of Meucci with the patent office. They had wanted to prepare a patent application, but the partners did not provide the $250 fee, so all that was prepared was a caveat, since the fee for that was only $20. However, the caveat did not contain a clear description of how the asserted invention would actually function. Meucci advocates claim the attorney erased margin notes Meucci had added to the document.[37]

Telettrofono Company[edit]

In 1872, Meucci and his friend Angelo Bertolino went to Edward B. Grant, Vice President of American District Telegraph Co. of New York (not Western Union as sometimes stated), to ask for help. Meucci asked him for permission to test his apparatus on the company’s telegraph lines. He gave Grant a description of his prototype and a copy of his caveat. After waiting two years, Meucci went to Grant and asked for his documents back, but Grant allegedly told him they had been lost.[11]

Around 1873, a man named Bill Carroll from Boston, who had news about Meucci’s invention, asked him to construct a telephone for divers. This device should allow divers to communicate with people on the surface. In Meucci’s drawing, this device is essentially an electromagnetic telephone encapsulated to be waterproof.[11][38]

On 28 December 1874, Meucci’s Telettrofono patent caveat expired. Critics dispute the claim that Meucci could not afford to file for a patent or renew his caveat, as he filed for and was granted full patents in 1872, 1873, 1875, and 1876, at the cost of $35 each, as well as one additional $10 patent caveat, all totaling $150, for inventions unrelated to the telephone.[16][17][39]

After Bell secured his patents in 1876 and subsequent years, the Bell Telephone Company filed suit in court against the Globe Telephone Company (amongst many others) for patent infringement. Purportedly too poor to hire a legal team, Meucci was represented only by lawyer Joe Melli, an orphan whom Meucci treated as his own son. While American Bell Telephone Company v. Globe Telephone Company, Antonio Meucci, et al. was still proceeding, Bell also became involved with The U.S. Government v. American Bell Telephone Company, instigated by the Pan-Electric Telephone Company, which had secretly given Augustus Hill Garland the U.S. Attorney General 10% of its shares, employed him as a director, and then asked him to void Bell’s patent. Had he succeeded in overturning Bell’s patent, the U.S. Attorney General stood to become exceedingly rich by reason of his shares.[40][41][42]

Trial[edit]

The Havana experiments were briefly mentioned in a letter by Meucci, published by Il Commercio di Genova of 1 December 1865 and by L’Eco d’Italia of 21 October 1865 (both existing today).[43]

An important piece of evidence brought up in the trial was Meucci’s Memorandum Book, which contained Meucci’s noted drawings and records between 1862 and 1882. In the trial, Antonio Meucci was accused of having produced records after Bell’s invention and back-dated them. As proof, the prosecutor brought forward the fact that the Rider & Clark company was founded only in 1863. At trial, Meucci said William E. Rider himself, one of the owners, had given him a copy of the memorandum book in 1862; however, Meucci was not believed.[38]

On 13 January 1887, the United States Government moved to annul the patent issued to Bell on the grounds of fraud and misrepresentation. After a series of decisions and reversals, the Bell company won a decision in the Supreme Court, though a couple of the original claims from the lower court cases were left undecided.[44][45] By the time that the trial wound its way through nine years of legal battles, the U.S. prosecuting attorney had died and the two Bell patents (No. 174,465 dated 7 March 1876 and No. 186,787 dated 30 January 1877) were no longer in effect, although the presiding judges agreed to continue the proceedings due to the case’s importance as a «precedent».

With a change in administration and charges of conflict of interest (on both sides) arising from the original trial, the U.S. Attorney General dropped the lawsuit on 30 November 1897 leaving several issues undecided on the merits. During a deposition filed for the 1887 trial, Meucci claimed to have created the first working model of a telephone in Italy in 1834. In 1886, in the first of three cases in which he was involved, Meucci took the stand as a witness in the hopes of establishing his invention’s priority. Meucci’s evidence in this case was disputed due to lack of material evidence of his inventions as his working models were reportedly lost at the laboratory of American District Telegraph (ADT) of New York. ADT did not merge with Western Union to become its subsidiary until 1901.[46][47]

Meucci’s patent caveat had described a lover’s telegraph, which transmitted sound vibrations mechanically across a taut wire, a conclusion that was also noted in various reviews («The court further held that the caveat of Meucci did not describe any elements of an electric speaking telephone …», and «The court held that Meucci’s device consisted of a mechanical telephone consisting of a mouthpiece and an earpiece connected by a wire, and that beyond this the invention of Meucci was only imagination.»)[48][49] Meucci’s work, like many other inventors of the period, was based on earlier acoustic principles and despite evidence of earlier experiments, the final case involving Meucci was eventually dropped upon his death.[50]

Death[edit]

Meucci became ill in March 1889,[2] and died on 18 October 1889 in Clifton, Staten Island, New York.[51]

Invention of the telephone[edit]

There has been much dispute over who deserves recognition as the first inventor of the telephone, although Bell was credited with being the first to transmit articulate speech by undulatory currents of electricity. The Federazione Italiana di Elettrotecnica has devoted a museum to Meucci making a chronology of his inventing the telephone and tracing the history of the two trials opposing Meucci and Bell.[52][53] They support the claim that Antonio Meucci was the real inventor of the telephone.[54]

However, some scholars outside Italy do not recognize the claims that Meucci’s device had any bearing on the development of the telephone. Tomas Farley also writes that, «Nearly every scholar agrees that Bell and Watson were the first to transmit intelligible speech by electrical means. Others transmitted a sound or a click or a buzz but our boys [Bell and Watson] were the first to transmit speech one could understand.»[55]

In 1834 Meucci constructed a kind of acoustic telephone as a way to communicate between the stage and control room at the theatre «Teatro della Pergola» in Florence. This telephone was constructed on the model of pipe-telephones on ships and is still functional.[citation needed]

In 1848 Meucci developed a popular method of using electric shocks to treat rheumatism. He used to give his patients two conductors linked to 60 Bunsen batteries and ending with a cork. He also kept two conductors linked to the same Bunsen batteries. He used to sit in his laboratory, while the Bunsen batteries were placed in a second room and his patients in a third room. In 1849 while providing a treatment to a patient with a 114V electrical discharge, in his laboratory Meucci is claimed to have heard his patient’s scream through the piece of copper wire that was between them, from the conductors he was keeping near his ear. His intuition was that the «tongue» of copper wire vibrated just like a leave of an electroscope—which meant there was an electrostatic effect. To continue the experiment without hurting his patient, Meucci covered the copper wire with a piece of paper. Through this device he claimed to hear an unarticulated human voice. He called this device «telegrafo parlante» (talking telegraph).[12][dead link]

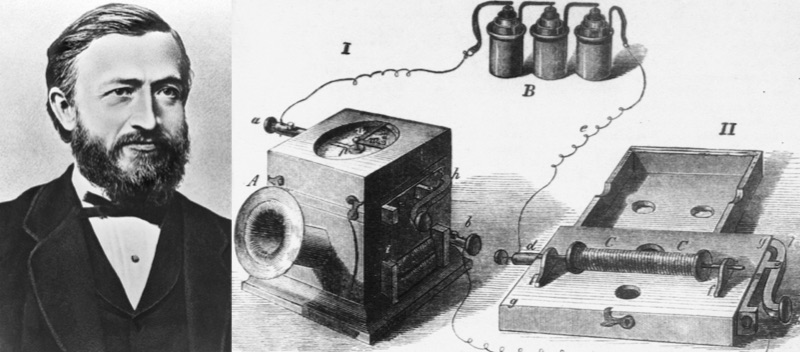

On the basis of this prototype, some claim Meucci worked on more than 30 kinds of telephones. In the beginning, he was inspired by the telegraph. Different from other pioneers of the telephone—such as Charles Bourseul, Philipp Reis, Innocenzo Manzetti, and others—he did not think about transmitting voice by using the principle of the telegraph key (in scientific jargon, the «make-and-break» method). Instead, he looked for a «continuous» solution, meaning one that didn’t interrupt the electric flux. In 1856, Meucci reportedly constructed the first electromagnetic telephone, made of an electromagnet with a nucleus in the shape of a horseshoe bat, a diaphragm of animal skin, stiffened with potassium dichromate and a metal disk stuck in the middle. The instrument was housed in a cylindrical carton box. He purportedly constructed it to connect his second-floor bedroom to his basement laboratory, and thus communicate with his invalid wife.[citation needed]

Meucci separated the two directions of transmission to eliminate the so-called «local effect»—using what we would call today a four-wire-circuit. He constructed a simple calling system with a telegraphic manipulator that short-circuited the instrument of the calling person to make a succession of impulses (clicks) that were louder than normal conversation.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] Aware that his device required a bigger band than a telegraph, he found some means to avoid the so-called «skin effect» through superficial treatment of the conductor or by acting on the material (copper instead of iron).[dubious – discuss][citation needed]

In 1864, Meucci claimed to have made what he felt was his best device, using an iron diaphragm with optimized thickness and tightly clamped along its rim. The instrument was housed in a shaving-soap box, whose cover clamped the diaphragm. In August 1870, Meucci reportedly obtained transmission of articulate human voice at a mile distance by using as a conductor a copper wire insulated by cotton. He called his device «telettrofono». Drawings and notes by Antonio Meucci with a claimed date of 27 September 1870 show that Meucci understood inductive loading on long-distance telephone lines 30 years before any other scientists. The question of whether Bell was the true inventor of the telephone is perhaps the single most litigated fact in U.S. history, and the Bell patents were defended in some 600 cases. Meucci was a defendant in American Bell Telephone Co. v. Globe Telephone Co. and others (the court’s findings, reported in 31 Fed. Rep. 729).[citation needed]

In his History of the Telephone, Herbert Newton Casson wrote:

To bait the Bell Company became almost a national sport. Any sort of claimant, with any sort of wild tale of prior invention, could find a speculator to support him. On they came, a motley array, ‘some in rags, some on nags, and some in velvet gowns.’ One of them claimed to have done wonders with an iron hoop and a file in 1867; a second had a marvellous table with glass legs; a third swore that he had made a telephone in 1860, but did not know what it was until he saw Bell’s patent; and a fourth told a vivid story of having heard a bullfrog croak via a telegraph wire which was strung into a certain cellar in Racine, in 1851.[56]

Judge Wallace’s ruling was bitterly regarded by historian Giovanni Schiavo as a miscarriage of justice.[57]

2002 U.S. Congressional resolution[edit]

In 2002, on the initiative of U.S. Representative Vito Fossella (R-NY), in cooperation with an Italian-American deputation, the U.S. House of Representatives passed United States HRes. 269 on Antonio Meucci stating «that the life and achievements of Antonio Meucci should be recognized, and his work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged.» According to the preamble, «if Meucci had been able to pay the $10 fee to maintain the caveat after 1874, no patent could have been issued to Bell.»[58][55] The resolution’s sponsor described it as «a message that rings loud and clear recognizing the true inventor of the telephone, Antonio Meucci.»[59]

In 2002, some news articles reported that «the resolution said his ‘telettrofono’, demonstrated in New York in 1860, made him the inventor of the telephone in the place of Bell, who took out a patent 16 years later.»[4][26]

A similar resolution was introduced to the U.S. Senate but no vote was held on the resolution.[60][61][62]

Despite the House of Representatives resolution, its interpretation as supporting Meucci’s claim as the inventor of the telephone remains disputed, as the resolution only referred to «his work in the invention of» the telephone rather than a direct assertion that he was the inventor of the telephone.[63][40][64]

The House of Commons of Canada responded ten days later by unanimously passing a parliamentary motion stating that Alexander Graham Bell was the inventor of the telephone.[65][66]

The Italian newspaper La Repubblica hailed the vote to recognize Meucci as a belated comeuppance for Bell.[4]

Garibaldi–Meucci Museum[edit]

The Order of the Sons of Italy in America maintains a Garibaldi–Meucci Museum on Staten Island. The museum is located in a house that was built in 1840, purchased by Meucci in 1850, and rented to Giuseppe Garibaldi from 1850 to 1854. Exhibits include Meucci’s models and drawing and pictures relating to his life.[67][68]

Other inventions[edit]

This list is also taken from Basilio Catania’s historical reconstruction.[69][70]

- 1825 Chemical compound to be used as an improved propellant in fireworks

- 1834 In Florence’s Teatro della Pergola, he sets up a «pipe telephone» to communicate from the stage to the maneuver trellis-work, at about eighteen meters height.

- 1840 Improved filters and chemical processing of waters supplying the city of Havana, Cuba.

- 1844 First electroplating factory of the Americas, set up in Havana, Cuba. Previously, objects to be electroplated were sent to Paris.

- 1846 Improved apparatus for electrotherapy, featuring a pulsed current breaker with rotating cross.

- 1847 Restructuring of the Tacón Theater in Havana, following a hurricane. Meucci conceived a new structure of the roof and ventilation system, to avoid the roof to be taken off in like situations.

- 1848 Astronomical observations by means of a marine telescope worth $280.

- 1849 Chemical process for the preservation of corpses, to cope with the high demand for bodies of immigrants to be sent to Europe, avoiding decomposition during the many weeks navigation.

- 1849 First invention of electrical transmission of speech.

- 1850-1851 First stearic candle factory of the Americas, set up in Clifton, New York.

- 1855 Realization of celestas, with crystal bars instead of steel, and pianos (one is on display at the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, in Rosebank, New York)

- 1856 First lager beer factory of Staten Island, the Clifton Brewery, in Clifton, New York

- 1858–1860 Invention of paraffin candle, U.S. Patent 22,739 on a candle mold for the same and U.S. Patent 30,180 on a rotating blade device for finishing the same.

- 1860 First paraffin candle factory in the world, the New York Paraffine Candle Co., set up in Clifton, New York, early in 1860, then moved to Stapleton, New York. It produced over 1,000 candles per day.

- 1860 Experiments on the use of dry batteries in electrical traction and other industrial applications.

- 1860 Process to turn red corals into a pink color (more valued), as requested by Enrico Bendelari, a merchant of New York.

- 1862 U.S. Patent 36,192 on a kerosene lamp that generates a very bright flame, without smoke, (therefore not needing a glass tube), thanks to electricity developed by two thin platinum plates embracing the flame.

- 1862–1863 Process for treating and bleaching oil or kerosene to obtain 185 oils for paint, U.S. Patent 36,419 and U.S. Patent 38,714. «Antonio Meucci Patent Oil» was sold by Rider & Clark Co., 51 Broad Street, New York, and exported to Europe.

- 1864 Invention of new, more destructive ammunition for guns and cannons, proposed to the US army and to General Giuseppe Garibaldi.

- 1864–1865 Processes to obtain paper pulp from wood or other vegetable substances, U.S. Patent 44,735, U.S. Patent 47,068 and U.S. Patent 53,165. Associated Press was interested in producing paper with this process, which was also the first to introduce the recovery of the leaching liquor.

- 1865 Process for making wicks out of vegetable fiber, U.S. Patent 46,607.

- 1867 A paper factory, the «Perth Amboy Fiber Co.,» was set up, in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. The paper pulp was obtained from either marsh grass or wood. It was the first to recycle waste paper.

- 1871 U.S. Patent 122,478 for «Effervescent Drinks,» fruit-vitamin rich drinks that Meucci found useful during his recovery from the wounds and burns caused by the explosion of the Westfield ferry.

- 1871 Filed a patent caveat, (not a ‘patent’) for a telephone device in December with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- 1873 U.S. Patent 142,071 for «Sauce for Food.» According to Roberto Merloni, general manager of the Italian STAR company, this patent anticipates modern food technologies.

- 1873 Conception of a screw steamer suitable for navigation in canals

- 1874 Process for refining crude oil (caveat)

- 1875 Filter for tea or coffee, similar to those used in present-day coffee machines

- 1875 Household utensil (description not available) usefulness to cheapness, that will find a ready sale

- 1875 U.S. Patent 168,273 «Lactometer,» for chemically detecting adulterations of milk. It anticipates by fifteen years the well-known Babcock test.

- 1875 Upon request by Giuseppe Tagliabue (a Physical Instruments maker of Brooklyn, New York), Meucci devises and manufactures several aneroid barometers of various shapes.

- 1875 Meucci decided not to renew his telephone caveat, thus enabling Bell to get a patent.

- 1876 U.S. Patent 183,062 «Hygrometer,» which was a marked improvement over the popular hair-hygrometer of the time. He set up a small factory in Staten Island for fabrication of the same.

- 1878 Method for preventing noise on elevated railways, a problem much felt at the time in New York.

- 1878 Process for fabricating ornamental paraffin candles for Christmas trees.

- 1880 US patent application «Wire for Electrical Purposes»

- 1881 Process for making postage and revenue stamps.

- 1883 U.S. Patent 279,492 for «Plastic Paste,» as hard and tenacious to be suitable for billiard balls.

Patents[edit]

US patent images in TIFF format

- U.S. Patent 22,739 1859 – Candle mold

- U.S. Patent 30,180 1860 – Candle mold

- U.S. Patent 36,192 1862 – Lamp burner

- U.S. Patent 36,419 1862 – Improvement in treating kerosene

- U.S. Patent 38,714 1863 – Improvement in preparing hydrocarbon liquid

- U.S. Patent 44,735 1864 – Improved process for removing mineral, gummy, and resinous substances from vegetables

- U.S. Patent 46,607 1865 – Improved method of making wicks

- U.S. Patent 47,068 1865 – Improved process for removing mineral, gummy, and resinous substances from vegetables

- U.S. Patent 53,165 1866 – Improved process for making paper-pulp from wood

- U.S. Patent 122,478 1872 – Improved method of manufacturing effervescent drinks from fruits

- U.S. Patent 142,071 1873 – Improvement in sauces for food

- U.S. Patent 168,273 1875 – Method of testing milk

- U.S. Patent 183,062 1876 – Hygrometer

- U.S. Patent 279,492 1883 – Plastic paste for billiard balls and vases

See also[edit]

- The Telephone Cases

- Timeline of the telephone

- Emile Berliner

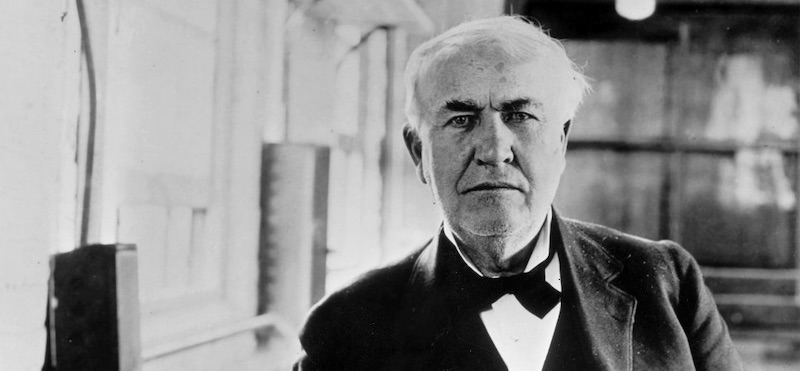

- Thomas Edison

- Elisha Gray

References[edit]

- ^ «Meucci, Antonio». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022.

- ^ a b «Antonio Meucci’s Illness». The New York Times, 9 March 1889; accessed 25 February 2009.

- ^ Nese & Nicotra 1989, pp. 35–52.

- ^ a b c Carroll, Rory (17 June 2002). «Bell did not invent telephone, US rules». The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ Several Italian encyclopedias claim Meucci as the inventor of the telephone, including:

– the «Treccani»

– the Italian version of Microsoft digital encyclopedia, Encarta

– Enciclopedia Italiana di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti (Italian Encyclopedia of Science, Literature and Arts). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Meucci, Sandra. Antonio and the Electric Scream: The Man Who Invented the Telephone, Branden Books, Boston, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8283-2197-6, pp. 15–21, 24, 36–37, 47–52, 70–73, 92, 98, 100.

- ^ Manifestazioni per il bicentenario della nascita di Antonio Meucci, archive date 22 July 2011.

- ^ H.Res.269 Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives to honor the life and achievements of 19th Century Italian-American inventor Antonio Meucci, and his work in the invention of the telephone. 11 June 2002, retrieved 14 February 2022

- ^ Nese & Nicotra 1989, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Catania, Basilio. «Meucci, Antonio» (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e Catania, Basilio (December 2003). «Antonio Meucci, l’inventore del telefono» (PDF). Notiziario Tecnico Telecom Italia (in Italian). pp. 109–117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2007.

- ^ a b Meucci’s original drawings. Archived 10 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine Italian Society of Electrotechnics aei.it; accessed 15 June 2015. (in Italian).

- ^ «Il primo telefono elettromagnetico». 28 July 2010. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Antonio Meucci stamp, comunicazioni.it; archived 26 August 2003. (in Italian).

- ^ American Bell Telephone Co. v. Globe Telephone Co. (1887), via Scripophily.net. Archived 21 February 2004.

- ^ a b U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. «The Story of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office». Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office. Washington:IA-SuDocs, Rev. August 1988. iv, 50p. MC 89-8590. OCLC 19213162. SL 89-95-P. S/N 003-004-00640-4. $1.75. C 21.2:P 27/3/988 – – – – Note: the 1861 filing fee is listed on Pg. 11, and the 1922 filing fee is listed on page 22.

- ^ a b U.S.P.T.O. & Patent Model Association. Digital version of The Story of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office: (section) Act of 2 March 1861, 2001; retrieved from PatentModelAssociation.com website, 25 February 2011.

- ^ Campanella, Angelo (January 2007). «Antonio Meucci, The Speaking Telegraph, and The First Telephone». ResearchGate.

- ^ Caveat, p. 17 top

- ^ a b Caveat p. 17

- ^ Caveat p. 18

- ^ «metallic tube» in Caveat, p. 16 bottom.

- ^ Caveat pp. 17 bottom line – 18 top line

- ^ Caveat, p. 17 bottom.

- ^ Caveat p. 17, 3rd paragraph.

- ^ a b Estreich, Bob. Antonio Meucci: The Resolution; retrieved from BobsOldPhones.net website, 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b Bruce, Robert V. (1973). Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Cornell University Press, p. 272. ISBN 978-0316112512

- ^ a b Catania, Basilio (December 2002). «The U.S. Government Versus Alexander Graham Bell: An Important Acknowledgement for Antonio Meucci». Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 22 (6): 426–442. doi:10.1177/0270467602238886. S2CID 144185363. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Catania, Basilio (October 1992). Sulle tracce di Antonio Meucci – Appunti di viaggio (in Italian). L’Elettrotecnica, Vol. LXXIX, N. 10, Arti Grafiche Stefano Pinelli, Milano. pp. 973–984.

- ^ Profile, chezbasilio.org; accessed 15 June 2015.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Parke (22 June 1973). «Book Reviews: The Life and Work of Bell». Science. 180 (4092): 1268–1269. doi:10.1126/science.180.4092.1268.

It seems likely that Bruce’s narrative account of Bell’s invention of the telephone will—with its shading and emphasis—be the definitive one. Bruce’s treatment of rival telephone inventors is less convincing, however, simply because he labels them in such an offhand fashion – Daniel Drawbaugh, the ‘Charlatan’, Antonio Meucci, the ‘innocent’, Elisha Gray, whose ‘bitterness’ caused him ‘to lash out [at Bell]’.

- ^ The Telephone Claimed by Meucci, Scientific American, N. 464. Blackie and Son Limited. 22 November 1884. p. 7407.

- ^ The Telegraphic Journal & Electrical Review: The Philadelphia Electrical Exhibition. The Telegr. J. and Electr. Review. 11 October 1884. pp. 277–83.

- ^ Bruce 1973, p. 278.

- ^ Aitken, William (1939). Who Invented The Telephone?. London and Glasgow: Blackie and Son. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution: Person to Person – Exhibit Catalog, 100th Birthday of the Telephone, National Museum of History and Technology, December 1976.

- ^ Nese, Marco & Nicotra, Francesco. «Antonio Meucci, 1808–1889», Italy Magazine, Rome, 1989, p. 85.

- ^ a b «Antonio Meucci’s Memorandum Book», Italian Society of Electrotechnics. (in Italian). Archived 7 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Estreich Bob. Antonio Meucci: Twisting The Evidence, BobsOldPhones.net website, 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b Rockman, Howard B. «Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists.» IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society, Wiley-IEEE, 2004, pp. 107–109; ISBN 978-0-471-44998-0

- ^ «Augustus Hill Garland (1832–1899)», Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture website; retrieved 1 May 2009.

Note: according to this article: «Garland soon found himself embroiled in scandal. While Garland was in the Senate, he had become a stockholder in, and attorney for, the Pan-Electric Telephone Company, which was organized to form regional telephone companies using equipment developed by J. Harris Rogers. The equipment was similar to the Bell telephone, and that company soon brought suit for patent infringement. Soon after he became attorney general, Garland was asked to bring suit in the name of the United States to invalidate the Bell patent. He refused …»

However, in Rockman (2004), there is no mention of Garland refusing to do so, and moreover Garland had been given his shares in Pan-Electric, by the company, for free. - ^ «Augustus Hill Garland (1874–1877)», Old Statehouse Museum website; retrieved 1 May 2009.

Note: According to this biography: «He did, however, suffer scandal involving the patent for the telephone. The Attorney General’s office was intervening in a lawsuit attempting to break Bell’s monopoly of telephone technology, but it had come out that Garland owned stock in one of the companies that stood to benefit. This congressional investigation received public attention for nearly a year, and caused his work as attorney general to suffer.» - ^ Meucci profile, www.chezbasilio.org; accessed 15 June 2015.

- ^ «FindLaw’s United States Supreme Court case and opinions: U.S. v. American Bell Tel Co., 167 U.S. 224 (1897)». Findlaw.

- ^ United States v. American Bell Telephone Co., 128 U.S. 315 (1888), supreme.justia.com; accessed 15 June 2015.

- ^ Catania, Basilio. «Antonio Meucci – Questions and Answers: What did Meucci to bring his invention to the public?», Chezbasilio.org website; accessed 8 July 2009.

- ^ History of ADT, ADT.com website; retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ Rockman, Howard B.»Intellectual Property Law for Engineers and Scientists», IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society, Wiley-IEEE, 2004, pp. 107–09; ISBN 978-0-471-44998-0.

- ^ Grosvenor, Edwin S. «Memo on Misstatements of Fact in House Resolution 269 and Facts Relating to Antonio Meucci and the Invention of the Telephone», alecbell.org, 30 June 2002.

- ^ Bruce 1990 reprint [1973], pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-0801496912

- ^ «Funeral of Antonio Meucci». New York Times. 22 October 1889. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

The funeral services over the body of the Italian patriot, Antonio Meucci, will take place at Clifton, S.I., this forenoon at 10 o clock. …

- ^ L’invenzione del telefono da parte di Meucci e la sua sventurata e ingiusta conclusione, aei.it. (in Italian). Archived 6 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Museo Storico Virtuale dell’AEIT Sala Antonio Meucci, aei.it. (in Italian). Archived 10 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Antonio Meucci – Questions and Answers». www.chezbasilio.org.

- ^ a b Bellis, Mary. «Antonio Meucci and the invention of the telephone», inventors.about.com; accessed 15 June 2015.

- ^ Casson, Herbert N. «The History of the Telephone», Chicago, IL: McClurg, 1910, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Catania, Basilio (April 2003). Antonio Meucci: Una vita per la scienza e per l’Italia (in Italian). Istituto Superiore delle Comunicazioni e delle Tecnologie per l’Informazione.

- ^ House Resolution 269, dated 11 June 2002, written and sponsored by Rep. Vito Fossella.

- ^ «Rep. Fossella’s Resolution Honoring True Inventor of Telephone To Pass House Tonight». Office of Congressman Vito J. Fossella. 11 June 2002. Archived from the original on 24 January 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ United States Senate. Senate Resolution 223, 108th Congress (2003–2004), 10 September 2003; retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ U.S. Senate. «Submission of Concurrent and Senate Resolutions – (Senate – 10 September 2003)», U.S. Congress Thomas Website, p. S11349, 10 September 2003.

- ^ GovTrack.us. S.Res.223 (108th Congress); retrieved from GovTrack.us website on 28 February 2011.

- ^ Estreich, Bob. Antonio Meucci: (section) The Resolution; retrieved from BobsOldPhones.net website, 25 February 2011;

«the text of the Resolution DOES NOT acknowledge Meucci as the inventor of the telephone. It does acknowledge his early work on the telephone, but even this is open to question.» - ^ Bethune, Brian. «Did Bell steal the idea for the phone?», Macleans, 23 January 2008; retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ «House of Commons of Canada, Journals No. 211, 37th Parliament, 1st Session, No. 211 transcript». Hansard of the Government of Canada, 21 June 2002, p 1620/cumulative p. 13006, time mark: 1205; retrieved 29 April 2009. Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fox, Jim, «Bell’s Legacy Rings Out at his Homes», Globe and Mail, 17 August 2002.

- ^ «Welcome to the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum».

- ^ «The Garibaldi–Meucci Museum», StatenIslandUSA.com, Office of the Borough President.

- ^ Basilio Catania’s chronological list of Meucci’s inventions, chezbasilio.org; accessed 15 June 2015.

- ^ «Assessment of Meucci’s Inventions by Today’s Experts», chezbasilio.org; accessed 21 January 2020.

Further reading[edit]

Documents of the trial[edit]

- Antonio Meucci’s Deposition (New York, 7 December 1885 – January 1886), New York Public Library – Annex. National Archives & Records Administration. New York, NY – File: Records of the U.S. Circuit Court, Southern District of New York, The American Bell Telephone Co. et al. v. The Globe Telephone Co. et al.

- Affidavit of Michael Lemmi (Translation of Meucci’s Memorandum book) sworn September 28, 1885. National Archives & Records Administration. Washington, D.C. – RG48. Interior Dept. file 4513–1885. Enclosure 2.

Scientific and historic research[edit]

- Catania Basilio, 2002, «The U.S. Government Versus Alexander Graham Bell: An Important Acknowledgment», Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 22: 426–442

- Scientific A «American Supplement No. 520, 19 December 1885

- Rossi Adolfo, Un Italiano in America. La Cisalpina, Milano 1881.

- Schiavo, Giovanni E., Antonio Meucci : inventor of the telephone, New York : The Vigo press, 1958, no ISBN, ITICCUSBL234690 (Italian National Library System).

- Sterling Christopher H., 2004, CBQ Review Essay: History of the Telephone (Part One): Invention, Innovation, and Impact. Communication Booknotes Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 222–241. doi:10.1207/s15326896cbq3504_1

- Vassilatos Gerry Lost Science (ISBN 0-945685-25-4, review)

• Pizer, Russell A. The Tangled Web of Patent #174465 Pub: AuthorHouse ©2009, 347pp. Pizer’s book contains 37 illustrations. Of extreme importance is research via the 1971 Ph.D. dissertation of Dr. Rosario Tosiello who’s PhD advisor at Boston University was Robert V. Bruce the 1973 author of «Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solute.» The ‘»Tangled Web of Patent #174465″ shows that A. G. Bell did not ever file a patent for the telephone and the Patent #174465 did not mention the word «telephone.» The patent application was submitted by Attorney Pollok at the insistence of A. G. Bell’s soon-to-be father-in-law, Gradiner Green Hubbard. A. G. Bell was unaware Anthony Pollock had submitted the application at the time of its submission.

Other media[edit]

- John Bedini’s Antonio Meucci-page Hearing Through Wires.

- Bellis Mary «The History of the Telephone – Antonio Meucci»

- Dossena Tiziano Thomas, Meucci, Forgotten Italian Genius, Bridge Apulia N.4, 1999

- Dossena Tiziano Thomas, Meucci, The Inventor of the Telephone, Bridge Apulia N.8, 2002

- Fenster Julie M., 2006, Inventing the Telephone – And Triggering All-Out Patent War, AmericanHeritage.com

External links[edit]

US Congress Resolution 269[edit]

- Bill Number H.RES.269 for the 107th Congress Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Summary and status of Resolution 269 Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Museums and celebrations[edit]

- The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum

- The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum (Staten Island site)

- Italian National Committee for the Meucci bicentennial, 1808–2008 (archived)

- Antonio Meucci – L’invenzione del telefono in La storia siamo noi Italian TV program on Italy’s national public broadcasting company RAI

- Antonio Meucci Centre at COPRAS (Italian-Canadian heritage website)

- Dr. Basilio Catania Website (website of a telecommunications researcher and historian with an extensive collection of Meucci documentation, including The Proofs of Meucci’s Priority)

- Antonio Meucci on BobsOldPhones (by Bob Estreich, an Australian telephone researcher and historian)

- Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers at the Library of Congress, 1862–1939

- Alexander Graham Bell Institute at Cape Breton University

| Antonio Meucci | |

|---|---|

Meucci in 1878 | |

| Born | 13 April 1808 Florence, First French Empire (present-day Italy) |

| Died | 18 October 1889 (aged 81) Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Accademia di Belle Arti |

| Known for | Inventing a telephone-like device, innovator, businessman, supporter of Italian unification |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Communication devices, manufacturing, chemical and mechanical engineering, chemical and food patents |

Antonio Santi Giuseppe Meucci ( may-OO-chee,[1] Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo meˈuttʃi]; 13 April 1808 – 18 October 1889) was an Italian inventor and an associate of Giuseppe Garibaldi, a major political figure in the history of Italy.[2][3] Meucci is best known for developing a voice-communication apparatus that several sources credit as the first telephone.[4][5]

Meucci set up a form of voice-communication link in his Staten Island, New York, home that connected the second-floor bedroom to his laboratory.[6] He submitted a patent caveat for his telephonic device to the U.S. Patent Office in 1871, but there was no mention of electromagnetic transmission of vocal sound in his caveat. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was granted a patent for the electromagnetic transmission of vocal sound by undulatory electric current.[6] Despite the longstanding general crediting of Bell with the accomplishment, the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities supported celebrations of Meucci’s 200th birthday in 2008 using the title «Inventore del telefono» (Inventor of the telephone).[7] The U.S. House of Representatives in a resolution in 2002 also acknowledged Meucci’s work in the invention of the telephone,[8] although the U.S. Senate did not join the resolution and the interpretation of the resolution is disputed.

Early life[edit]

Meucci was born at Via dei Serragli 44 in the San Frediano borough of Florence, First French Empire (now in the Italian Republic), on 13 April 1808, as the first of nine children to Amatis Meucci and Domenica Pepi.[6] Amatis was at times a government clerk and a member of the local police, and Domenica was principally a homemaker. Four of Meucci’s siblings did not survive childhood.[9]

In November 1821, at the age of 13, he was admitted to Florence Academy of Fine Arts as its youngest student, where he studied chemical and mechanical engineering.[6] He ceased full-time studies two years later due to insufficient funds, but continued studying part-time after obtaining employment as an assistant gatekeeper and customs official for the Florentine government.[6]

In May 1825, because of the celebrations for the childbirth of Marie Anna of Saxony, wife of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Meucci conceived a powerful propellant mixture for flares. Unfortunately the fireworks went out of his control, causing damages and injuries in the celebration’s square. Meucci was arrested and suspected of conspiracy against the Grand Duchy.[10]

Meucci later became employed at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence as a stage technician, assisting Artemio Canovetti.[11]

In 1834 Meucci constructed a type of acoustic telephone to communicate between the stage and control room at the Teatro of Pergola. This telephone was constructed on the principles of pipe-telephones used on ships and still functions. He married costume designer Esterre Mochi, who was employed in the same theatre, on 7 August 1834.[6]

Havana, Cuba[edit]

In October 1835, Meucci and his wife emigrated to Cuba, then a Spanish province, where Meucci accepted a job at what was then called the Teatro Tacón in Havana (at the time, the greatest theater in the Americas). In Havana he constructed a system for water purification and reconstructed the Gran Teatro.[11][6]

In 1848 his contract with the governor expired. Meucci was asked by a friend’s doctors to work on Franz Anton Mesmer’s therapy system on patients with rheumatism. In 1849, he developed a popular method of using electric shocks to treat illness and subsequently experimentally developed a device through which one could hear inarticulate human voice. He called this device «telegrafo parlante» (talking telegraph).[12]

In 1850, the third renewal of Meucci’s contract with Don Francisco Martí y Torrens expired, and his friendship with General Giuseppe Garibaldi made him a suspect citizen in Cuba. On the other hand, the fame reached by Samuel F. B. Morse in the United States encouraged Meucci to make his living through inventions.[6]

Staten Island, New York[edit]

On 13 April 1850, Meucci and his wife emigrated to the United States, taking with them approximately 26,000 pesos fuertes in savings (approximately $500,000 in 2010 dollars), and settled in the Clifton area of Staten Island, New York, New York.[6]

The Meuccis would live there for the remainder of their lives. On Staten Island he helped several countrymen committed to the Italian unification movement and who had escaped political persecution. Meucci invested the substantial capital he had earned in Cuba into a tallow candle factory (the first of this kind in America) employing several Italian exiles. For two years Meucci hosted friends at his cottage, including General Giuseppe Garibaldi, and Colonel Paolo Bovi Campeggi, who arrived in New York two months after Meucci. They worked in Meucci’s factory.[citation needed]

In 1854, Meucci’s wife Esterre became an invalid due to rheumatoid arthritis.[citation needed] Meucci continued his experiments.

Electromagnetic telephone[edit]

Meucci studied the principles of electromagnetic voice transmission for many years[citation needed] and was able to transmit his voice through wires in 1856. He installed a telephone-like device within his house in order to communicate with his wife, who was ill at the time.[6] Some of Meucci’s notes written in 1857 describe the basic principle of electromagnetic voice transmission or in other words, the telephone:

Consiste in un diaframma vibrante e in un magnete elettrizzato da un filo a spirale che lo avvolge. Vibrando, il diaframma altera la corrente del magnete. Queste alterazioni di corrente, trasmesse all’altro capo del filo, imprimono analoghe vibrazioni al diaframma ricevente e riproducono la parola.

Translated:

It consists of a vibrating diaphragm and a magnet electrified by a spiral wire that wraps around it. The vibrating diaphragm alters the current of the magnet. These alterations of current, transmitted to the other end of the wire, create analogous vibrations of the receiving diaphragm and reproduce the word.

Meucci devised an electromagnetic telephone as a way of connecting his second-floor bedroom to his basement laboratory, and thus being able to communicate with his wife.[13] Between 1856 and 1870, Meucci developed more than 30 different kinds of telephones on the basis of this prototype.

A postage stamp was produced in Italy in 2003 that featured a portrait of Meucci.[14]

Around 1858, artist Nestore Corradi sketched Meucci’s communication concept. His drawing was used to accompany the stamp in a commemorative publication of the Italian Postal and Telegraph Society.[14]

Meucci intended to develop his prototype but did not have the financial means to keep his company afloat in order to finance his invention. His candle factory went bankrupt and Meucci was forced to unsuccessfully seek funds from rich Italian families. In 1860, he asked his friend Enrico Bandelari to look for Italian capitalists willing to finance his project. However, military expeditions led by Garibaldi in Italy had made the political situation in that country too unstable for anybody to invest.[11]

Bankruptcy[edit]

At the same time, Meucci was led to poverty by some fraudulent debtors. On 13 November 1861 his cottage was auctioned. The purchaser allowed the Meuccis to live in the cottage without paying rent, but Meucci’s private finances dwindled and he soon had to live on public funds and by depending on his friends. As mentioned in William J. Wallace’s ruling,[15] during the years 1859–1861, Meucci was in close business and social relations with William E. Ryder, who invested money in Meucci’s inventions and paid the expenses of his experiments. Their close working friendship continued until 1867.[citation needed]

In August 1870, Meucci reportedly was able to capture a transmission of articulated human voice at the distance of a mile by using a copper plate as a conductor, insulated by cotton. He called this device the «telettrofono». While he was recovering from injuries that befell him in a boiler explosion aboard a Staten Island ferry, the Westfield, Meucci’s financial and health state was so bad that his wife sold his drawings and devices to a second-hand dealer to raise money.[citation needed]

Patent caveat[edit]

On 12 December 1871 Meucci set up an agreement with Angelo Zilio Grandi (Secretary of the Italian Consulate in New York), Angelo Antonio Tremeschin (entrepreneur), Sereno G.P. Breguglia Tremeschin (businessman), in order to constitute the Telettrofono Company. The constitution was notarized by Angelo Bertolino, a Notary Public of New York. Although their society funded him with $20, only $15 was needed to file for a full patent application.[16][17] The caveat his lawyer submitted to the US Patent Office on 28 December 1871 was numbered 3335 and titled «Sound Telegraph».

The following is the text of Meucci’s caveat, omitting legal details of the Petition, Oath, and Jurat:[18]

CAVEAT

The petition of Antonio Meucci, of Clifton, in the County of Richmond and State of New York, respectfully represents:

That he has made certain improvements in Sound Telegraphs, …

The following is a description of the invention, sufficiently in detail for the purposes of this caveat.

I employ the well-known conducting effect of continuous metallic conductors as a medium for sound, and increases the effect by electrically insulating both the conductor and the parties who are communicating. It forms a Speaking Telegraph, without the necessity for any hollow tube.

I claim that a portion or the whole of the effect may also be realized by a corresponding arrangement with a metallic tube. I believe that some metals will serve better than others, but propose to try all kinds of metals.

The system on which I propose to operate and calculate consists in isolating two persons, separated at considerable distance from each other, by placing them upon glass insulators; employing glass, for example, at the foot of the chair or bench on which each sits, and putting them in communication by means of a telegraph wire.

I believe it preferable to have the wire of larger area than that ordinarily employed in the electric telegraph, but will experiment on this. Each of these persons holds to his mouth an instrument analogous to a speaking trumpet, in which the word may easily be pronounced, and the sound concentrated upon the wire. Another instrument is also applied to the ears, in order to receive the voice of the opposite party.

All these, to wit, the mouth utensil and the ear instruments, communicate to the wire at a short distance from the persons. The ear utensils being of a convex form, like a clock glass, enclose the whole exterior part of the ear, and make it easy and comfortable for the operator. The object is to bring distinctly to the hearing the word of the person at the opposite end of the telegraph.

To call attention, the party at the other end of the line may be warned by an electric telegraph signal, or a series of them. The apparatus for this purpose, and the skill in operating it, need be much less than for the ordinary telegraphing.

When my sound telegraph is in operation, the parties should remain alone in their respective rooms, and every practicable precaution should be taken to have the surroundings perfectly quiet. The closed mouth utensil or trumpet, and the enclosing the persons also in a room alone, both tend to prevent undue publicity to the communication.

I think it will be easy, by these means, to prevent the communication being understood by any but the proper persons.

It may be found practicable to work with the person sending the message insulated, and with the person receiving it, in the free electrical communication with the ground. Or these conditions may possibly be reversed and still operate with some success.

Both the conductors or utensils for mouth and ears should be, in fact I must say must be, metallic, and be so conditioned as to be good conductors of electricity.

I claim as my invention, and desire to have considered as such, for all the purposes of this Caveat,

The new invention herein set forth in all its details, combinations, and sub-combinations.

And more especially, I claim

First. A continuous sound conductor electrically insulated.

Second. The same adapted for telegraphing by sound or for conversation between distant parties electrically insulated.

Third. The employment of a sound conductor, which is also an electrical conductor, as a means of communication by sound between distant points.

Fourth. The same in combination with provisions for electrically insulating the sending and receiving parties.

Fifth. The mouthpiece or speaking utensil in combination with an electrically insulating conductor.

Sixth. The ear utensils or receiving vessels adapted to apply upon the ears in combination with an electrically insulating sound conductor.

Seventh. The entire system, comprising the electrical and sound conductor, insulated and furnished with a mouthpiece and ear pieces at each end, adapted to serve as specified.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand in presence of two subscribing witnesses.

ANTONIO MEUCCI

Witnesses:

Shirley McAndrew.

Fred’k Harper.

Endorsed:

Patent Office

Dec. 28, 1871

Analysis of Meucci’s caveat[edit]

Meucci repeatedly focused on insulating the electrical conductor and even insulating the people communicating, but does not explain why this would be desirable.[19] The mouth piece is like a «speaking trumpet» so that «the sound concentrated upon the wire» is communicated to the other person, but he does not say that the sound is converted to variable electrical conduction in the wire.[20] «Another instrument is also applied to the ears», but he does not say that variable electrical conduction in the wire is to be converted to sound.[20] In the third claim, he claims «a sound conductor which is also an electrical conductor, as a means of communication by sound»,[21] which is consistent with acoustic sound vibrations in the wire that get transmitted better if electrical conductors such as a wire or metallic tube are used.[22]

Meucci emphasizes that the conductors «for mouth and ears … must be metallic», but does not explain why this would be desirable.[23] He mentions «communication with the ground»[24] but does not suggest that a ground return must complete a circuit if only «the wire» (singular, not plural) is used between the sender’s mouth piece and the receiver’s ear piece, with one or the other person being electrically insulated from the ground by means of glass insulators («… consists in isolating two persons … by placing them upon glass insulators; employing glass, for example, at the foot of the chair or bench on which each sits, and putting them in communication by means of a telegraph wire»).[25]

Robert V. Bruce, a biographer of Bell, asserted that Meucci’s caveat could never have become a patent because it never described an electric telephone.[26][27]

Conflicting opinions of Meucci biographers[edit]

According to Bruce, Meucci’s own testimony as presented by Schiavo demonstrates that the Italian inventor «did not understand the basic principles of the telephone, either before or several years after Bell patented it.»[27]

Other researchers[who?] have pointed to inconsistencies and inaccuracies in Bruce’s account of the invention of the telephone, firstly with the name used by Meucci to describe his invention—Bruce refers to Meucci’s device as a «telephone», not as the «telettrofono». Bruce’s reporting of Meucci’s purported relationship with Dr. Seth R. Beckwith has been deemed inaccurate. Beckwith, a former surgeon and general manager of the Overland Telephone Company of New York, «had acquired a substantial knowledge in the telephonic field and had become an admirer of Meucci».[28] In 1885, he became general manager of the Globe Telephone Company, which had «started an action attempting to involve the government in hindering U.S. Bell’s monopoly.»[28] However, Meucci and his legal representative had cautioned Beckwith against misusing Meucci’s name for financial gain after Beckwith founded a company in New Jersey named the Meucci Telephone Company.[29][30][31]

Not only did Beckwith’s Globe Telephone Company base its claims against the Bell Telephone Company on Meucci’s caveat, but the claims were also supported by approximately 30 affidavits, which stated that Meucci had repeatedly built and used different types of electric telephones several years before Bell did.[32][33]

English historian William Aitken does not share Bruce’s viewpoint. Bruce indirectly referred to Meucci as «the silliest and weakest impostor»,[34] while Aitken has gone so far as to define Meucci as the first creator of an electrical telephone.[35]

Other recognition of Meucci’s work in the past came from the International Telecommunication Union, positing that Meucci’s work was one of the four precursors to Bell’s telephone,[citation needed] as well as from the Smithsonian Institution, which listed Meucci as one of the eight most important inventors of the telephone in a 1976 exhibit.[36]

Meucci and his business partners hired an attorney (J. D. Stetson), who filed a caveat on behalf of Meucci with the patent office. They had wanted to prepare a patent application, but the partners did not provide the $250 fee, so all that was prepared was a caveat, since the fee for that was only $20. However, the caveat did not contain a clear description of how the asserted invention would actually function. Meucci advocates claim the attorney erased margin notes Meucci had added to the document.[37]

Telettrofono Company[edit]

In 1872, Meucci and his friend Angelo Bertolino went to Edward B. Grant, Vice President of American District Telegraph Co. of New York (not Western Union as sometimes stated), to ask for help. Meucci asked him for permission to test his apparatus on the company’s telegraph lines. He gave Grant a description of his prototype and a copy of his caveat. After waiting two years, Meucci went to Grant and asked for his documents back, but Grant allegedly told him they had been lost.[11]

Around 1873, a man named Bill Carroll from Boston, who had news about Meucci’s invention, asked him to construct a telephone for divers. This device should allow divers to communicate with people on the surface. In Meucci’s drawing, this device is essentially an electromagnetic telephone encapsulated to be waterproof.[11][38]

On 28 December 1874, Meucci’s Telettrofono patent caveat expired. Critics dispute the claim that Meucci could not afford to file for a patent or renew his caveat, as he filed for and was granted full patents in 1872, 1873, 1875, and 1876, at the cost of $35 each, as well as one additional $10 patent caveat, all totaling $150, for inventions unrelated to the telephone.[16][17][39]

After Bell secured his patents in 1876 and subsequent years, the Bell Telephone Company filed suit in court against the Globe Telephone Company (amongst many others) for patent infringement. Purportedly too poor to hire a legal team, Meucci was represented only by lawyer Joe Melli, an orphan whom Meucci treated as his own son. While American Bell Telephone Company v. Globe Telephone Company, Antonio Meucci, et al. was still proceeding, Bell also became involved with The U.S. Government v. American Bell Telephone Company, instigated by the Pan-Electric Telephone Company, which had secretly given Augustus Hill Garland the U.S. Attorney General 10% of its shares, employed him as a director, and then asked him to void Bell’s patent. Had he succeeded in overturning Bell’s patent, the U.S. Attorney General stood to become exceedingly rich by reason of his shares.[40][41][42]

Trial[edit]

The Havana experiments were briefly mentioned in a letter by Meucci, published by Il Commercio di Genova of 1 December 1865 and by L’Eco d’Italia of 21 October 1865 (both existing today).[43]

An important piece of evidence brought up in the trial was Meucci’s Memorandum Book, which contained Meucci’s noted drawings and records between 1862 and 1882. In the trial, Antonio Meucci was accused of having produced records after Bell’s invention and back-dated them. As proof, the prosecutor brought forward the fact that the Rider & Clark company was founded only in 1863. At trial, Meucci said William E. Rider himself, one of the owners, had given him a copy of the memorandum book in 1862; however, Meucci was not believed.[38]

On 13 January 1887, the United States Government moved to annul the patent issued to Bell on the grounds of fraud and misrepresentation. After a series of decisions and reversals, the Bell company won a decision in the Supreme Court, though a couple of the original claims from the lower court cases were left undecided.[44][45] By the time that the trial wound its way through nine years of legal battles, the U.S. prosecuting attorney had died and the two Bell patents (No. 174,465 dated 7 March 1876 and No. 186,787 dated 30 January 1877) were no longer in effect, although the presiding judges agreed to continue the proceedings due to the case’s importance as a «precedent».

With a change in administration and charges of conflict of interest (on both sides) arising from the original trial, the U.S. Attorney General dropped the lawsuit on 30 November 1897 leaving several issues undecided on the merits. During a deposition filed for the 1887 trial, Meucci claimed to have created the first working model of a telephone in Italy in 1834. In 1886, in the first of three cases in which he was involved, Meucci took the stand as a witness in the hopes of establishing his invention’s priority. Meucci’s evidence in this case was disputed due to lack of material evidence of his inventions as his working models were reportedly lost at the laboratory of American District Telegraph (ADT) of New York. ADT did not merge with Western Union to become its subsidiary until 1901.[46][47]

Meucci’s patent caveat had described a lover’s telegraph, which transmitted sound vibrations mechanically across a taut wire, a conclusion that was also noted in various reviews («The court further held that the caveat of Meucci did not describe any elements of an electric speaking telephone …», and «The court held that Meucci’s device consisted of a mechanical telephone consisting of a mouthpiece and an earpiece connected by a wire, and that beyond this the invention of Meucci was only imagination.»)[48][49] Meucci’s work, like many other inventors of the period, was based on earlier acoustic principles and despite evidence of earlier experiments, the final case involving Meucci was eventually dropped upon his death.[50]

Death[edit]

Meucci became ill in March 1889,[2] and died on 18 October 1889 in Clifton, Staten Island, New York.[51]

Invention of the telephone[edit]

There has been much dispute over who deserves recognition as the first inventor of the telephone, although Bell was credited with being the first to transmit articulate speech by undulatory currents of electricity. The Federazione Italiana di Elettrotecnica has devoted a museum to Meucci making a chronology of his inventing the telephone and tracing the history of the two trials opposing Meucci and Bell.[52][53] They support the claim that Antonio Meucci was the real inventor of the telephone.[54]

However, some scholars outside Italy do not recognize the claims that Meucci’s device had any bearing on the development of the telephone. Tomas Farley also writes that, «Nearly every scholar agrees that Bell and Watson were the first to transmit intelligible speech by electrical means. Others transmitted a sound or a click or a buzz but our boys [Bell and Watson] were the first to transmit speech one could understand.»[55]

In 1834 Meucci constructed a kind of acoustic telephone as a way to communicate between the stage and control room at the theatre «Teatro della Pergola» in Florence. This telephone was constructed on the model of pipe-telephones on ships and is still functional.[citation needed]

In 1848 Meucci developed a popular method of using electric shocks to treat rheumatism. He used to give his patients two conductors linked to 60 Bunsen batteries and ending with a cork. He also kept two conductors linked to the same Bunsen batteries. He used to sit in his laboratory, while the Bunsen batteries were placed in a second room and his patients in a third room. In 1849 while providing a treatment to a patient with a 114V electrical discharge, in his laboratory Meucci is claimed to have heard his patient’s scream through the piece of copper wire that was between them, from the conductors he was keeping near his ear. His intuition was that the «tongue» of copper wire vibrated just like a leave of an electroscope—which meant there was an electrostatic effect. To continue the experiment without hurting his patient, Meucci covered the copper wire with a piece of paper. Through this device he claimed to hear an unarticulated human voice. He called this device «telegrafo parlante» (talking telegraph).[12][dead link]