| Molybdenum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (mə-LIB-də-nəm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mo) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molybdenum in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 42 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d5 5s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 13, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2896 K (2623 °C, 4753 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 4912 K (4639 °C, 8382 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 10.28 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 9.33 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 37.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 598 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.06 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4, −2, −1, 0, +1,[2] +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 139 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 154±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of molybdenum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5400 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 4.8 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 138 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal diffusivity | 54.3 mm2/s (at 300 K)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 53.4 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +89.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 329 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 126 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 230 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1400–2740 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 1370–2500 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-98-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1778) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Peter Jacob Hjelm (1781) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of molybdenum

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Category: Molybdenum

| references |

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin molybdaenum, which is based on Ancient Greek Μόλυβδος molybdos, meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores.[6] Molybdenum minerals have been known throughout history, but the element was discovered (in the sense of differentiating it as a new entity from the mineral salts of other metals) in 1778 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele. The metal was first isolated in 1781 by Peter Jacob Hjelm.[7]

Molybdenum does not occur naturally as a free metal on Earth; it is found only in various oxidation states in minerals. The free element, a silvery metal with a grey cast, has the sixth-highest melting point of any element. It readily forms hard, stable carbides in alloys, and for this reason most of the world production of the element (about 80%) is used in steel alloys, including high-strength alloys and superalloys.

Most molybdenum compounds have low solubility in water, but when molybdenum-bearing minerals contact oxygen and water, the resulting molybdate ion MoO2−

4 is quite soluble. Industrially, molybdenum compounds (about 14% of world production of the element) are used in high-pressure and high-temperature applications as pigments and catalysts.

Molybdenum-bearing enzymes are by far the most common bacterial catalysts for breaking the chemical bond in atmospheric molecular nitrogen in the process of biological nitrogen fixation. At least 50 molybdenum enzymes are now known in bacteria, plants, and animals, although only bacterial and cyanobacterial enzymes are involved in nitrogen fixation. These nitrogenases contain an iron-molybdenum cofactor FeMoco, which is believed to contain either Mo(III) or Mo(IV).[8][9] This is distinct from the fully oxidized Mo(VI) found complexed with molybdopterin in all other molybdenum-bearing enzymes, which perform a variety of crucial functions.[10] The variety of crucial reactions catalyzed by these latter enzymes means that molybdenum is an essential element for all higher eukaryote organisms, including humans.

Characteristics[edit]

Physical properties[edit]

In its pure form, molybdenum is a silvery-grey metal with a Mohs hardness of 5.5 and a standard atomic weight of 95.95 g/mol.[11][12] It has a melting point of 2,623 °C (4,753 °F); of the naturally occurring elements, only tantalum, osmium, rhenium, tungsten, and carbon have higher melting points.[6] It has one of the lowest coefficients of thermal expansion among commercially used metals.[13]

Chemical properties[edit]

Molybdenum is a transition metal with an electronegativity of 2.16 on the Pauling scale. It does not visibly react with oxygen or water at room temperature. Weak oxidation of molybdenum starts at 300 °C (572 °F); bulk oxidation occurs at temperatures above 600 °C, resulting in molybdenum trioxide. Like many heavier transition metals, molybdenum shows little inclination to form a cation in aqueous solution, although the Mo3+ cation is known under carefully controlled conditions.[14]

Gaseous molybdenum consists of the diatomic species Mo2. That molecule is a singlet, with two unpaired electrons in bonding orbitals, in addition to 5 conventional bonds. The result is a sextuple bond.[15][16]

Isotopes[edit]

There are 35 known isotopes of molybdenum, ranging in atomic mass from 83 to 117, as well as four metastable nuclear isomers. Seven isotopes occur naturally, with atomic masses of 92, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, and 100. Of these naturally occurring isotopes, only molybdenum-100 is unstable.[17]

Molybdenum-98 is the most abundant isotope, comprising 24.14% of all molybdenum. Molybdenum-100 has a half-life of about 1019 y and undergoes double beta decay into ruthenium-100. All unstable isotopes of molybdenum decay into isotopes of niobium, technetium, and ruthenium. Of the synthetic radioisotopes, the most stable is 93Mo, with a half-life of 4,000 years.[18]

The most common isotopic molybdenum application involves molybdenum-99, which is a fission product. It is a parent radioisotope to the short-lived gamma-emitting daughter radioisotope technetium-99m, a nuclear isomer used in various imaging applications in medicine.[19]

In 2008, the Delft University of Technology applied for a patent on the molybdenum-98-based production of molybdenum-99.[20]

Compounds[edit]

Molybdenum forms chemical compounds in oxidation states −IV and from −II to +VI. Higher oxidation states are more relevant to its terrestrial occurrence and its biological roles, mid-level oxidation states are often associated with metal clusters, and very low oxidation states are typically associated with organomolybdenum compounds. Mo and W chemistry shows strong similarities. The relative rarity of molybdenum(III), for example, contrasts with the pervasiveness of the chromium(III) compounds. The highest oxidation state is seen in molybdenum(VI) oxide (MoO3), whereas the normal sulfur compound is molybdenum disulfide MoS2.[21]

| Oxidation state | Example[22][23] |

|---|---|

| −4 | Na 4[Mo(CO) 4] |

| −1 | Na 2[Mo 2(CO) 10] |

| 0 | Mo(CO) 6 |

| +1 | Na[C 6H 6Mo] |

| +2 | MoCl 2 |

| +3 | MoBr 3 |

| +4 | MoS 2 |

| +5 | MoCl 5 |

| +6 | MoF 6 |

From the perspective of commerce, the most important compounds are molybdenum disulfide (MoS

2) and molybdenum trioxide (MoO

3). The black disulfide is the main mineral. It is roasted in air to give the trioxide:[21]

- 2 MoS

2 + 7 O

2 → 2 MoO

3 + 4 SO

2

The trioxide, which is volatile at high temperatures, is the precursor to virtually all other Mo compounds as well as alloys. Molybdenum has several oxidation states, the most stable being +4 and +6 (bolded in the table at left).

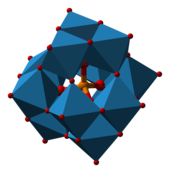

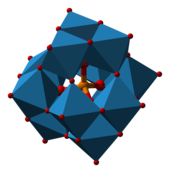

Molybdenum(VI) oxide is soluble in strong alkaline water, forming molybdates (MoO42−). Molybdates are weaker oxidants than chromates. They tend to form structurally complex oxyanions by condensation at lower pH values, such as [Mo7O24]6− and [Mo8O26]4−. Polymolybdates can incorporate other ions, forming polyoxometalates.[24] The dark-blue phosphorus-containing heteropolymolybdate P[Mo12O40]3− is used for the spectroscopic detection of phosphorus.[25] The broad range of oxidation states of molybdenum is reflected in various molybdenum chlorides:[21]

- Molybdenum(II) chloride MoCl2, which exists as the hexamer Mo6Cl12 and the related dianion [Mo6Cl14]2-.

- Molybdenum(III) chloride MoCl3, a dark red solid, which converts to the anion trianionic complex [MoCl6]3-.

- Molybdenum(IV) chloride MoCl4, a black solid, which adopts a polymeric structure.

- Molybdenum(V) chloride MoCl5 dark green solid, which adopts a dimeric structure.

- Molybdenum(VI) chloride MoCl6 is a black solid, which is monomeric and slowly decomposes to MoCl5 and Cl2 at room temperature.[26]

Like chromium and some other transition metals, molybdenum forms quadruple bonds, such as in Mo2(CH3COO)4 and [Mo2Cl8]4−.[21][27] The Lewis acid properties of the butyrate and perfluorobutyrate dimers, Mo2(O2CR)4 and Rh2(O2CR) 4, have been reported.[28]

The oxidation state 0 and lower are possible with carbon monoxide as ligand, such as in molybdenum hexacarbonyl, Mo(CO)6.[21][29]

History[edit]

Molybdenite—the principal ore from which molybdenum is now extracted—was previously known as molybdena. Molybdena was confused with and often utilized as though it were graphite. Like graphite, molybdenite can be used to blacken a surface or as a solid lubricant.[30] Even when molybdena was distinguishable from graphite, it was still confused with the common lead ore PbS (now called galena); the name comes from Ancient Greek Μόλυβδος molybdos, meaning lead.[13] (The Greek word itself has been proposed as a loanword from Anatolian Luvian and Lydian languages).[31]

Although (reportedly) molybdenum was deliberately alloyed with steel in one 14th-century Japanese sword (mfd. ca. 1330), that art was never employed widely and was later lost.[32][33] In the West in 1754, Bengt Andersson Qvist examined a sample of molybdenite and determined that it did not contain lead and thus was not galena.[34]

By 1778 Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele stated firmly that molybdena was (indeed) neither galena nor graphite.[35][36] Instead, Scheele correctly proposed that molybdena was an ore of a distinct new element, named molybdenum for the mineral in which it resided, and from which it might be isolated. Peter Jacob Hjelm successfully isolated molybdenum using carbon and linseed oil in 1781.[13][37]

For the next century, molybdenum had no industrial use. It was relatively scarce, the pure metal was difficult to extract, and the necessary techniques of metallurgy were immature.[38][39][40] Early molybdenum steel alloys showed great promise of increased hardness, but efforts to manufacture the alloys on a large scale were hampered with inconsistent results, a tendency toward brittleness, and recrystallization. In 1906, William D. Coolidge filed a patent for rendering molybdenum ductile, leading to applications as a heating element for high-temperature furnaces and as a support for tungsten-filament light bulbs; oxide formation and degradation require that molybdenum be physically sealed or held in an inert gas.[41] In 1913, Frank E. Elmore developed a froth flotation process to recover molybdenite from ores; flotation remains the primary isolation process.[42]

During World War I, demand for molybdenum spiked; it was used both in armor plating and as a substitute for tungsten in high-speed steels. Some British tanks were protected by 75 mm (3 in) manganese steel plating, but this proved to be ineffective. The manganese steel plates were replaced with much lighter 25 mm (1.0 in) molybdenum steel plates allowing for higher speed, greater maneuverability, and better protection.[13] The Germans also used molybdenum-doped steel for heavy artillery, like in the super-heavy howitzer Big Bertha,[43] because traditional steel melts at the temperatures produced by the propellant of the one ton shell.[44] After the war, demand plummeted until metallurgical advances allowed extensive development of peacetime applications. In World War II, molybdenum again saw strategic importance as a substitute for tungsten in steel alloys.[45]

Occurrence and production[edit]

Molybdenum is the 54th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust with an average of 1.5 parts per million and the 25th most abundant element in its oceans, with an average of 10 parts per billion; it is the 42nd most abundant element in the Universe.[13][46] The Russian Luna 24 mission discovered a molybdenum-bearing grain (1 × 0.6 µm) in a pyroxene fragment taken from Mare Crisium on the Moon.[47] The comparative rarity of molybdenum in the Earth’s crust is offset by its concentration in a number of water-insoluble ores, often combined with sulfur in the same way as copper, with which it is often found. Though molybdenum is found in such minerals as wulfenite (PbMoO4) and powellite (CaMoO4), the main commercial source is molybdenite (MoS2). Molybdenum is mined as a principal ore and is also recovered as a byproduct of copper and tungsten mining.[6]

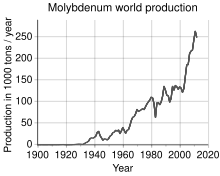

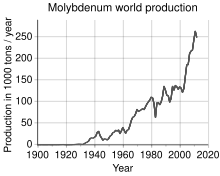

The world’s production of molybdenum was 250,000 tonnes in 2011, the largest producers being China (94,000 t), the United States (64,000 t), Chile (38,000 t), Peru (18,000 t) and Mexico (12,000 t). The total reserves are estimated at 10 million tonnes, and are mostly concentrated in China (4.3 Mt), the US (2.7 Mt) and Chile (1.2 Mt). By continent, 93% of world molybdenum production is about evenly shared between North America, South America (mainly in Chile), and China. Europe and the rest of Asia (mostly Armenia, Russia, Iran and Mongolia) produce the remainder.[48]

In molybdenite processing, the ore is first roasted in air at a temperature of 700 °C (1,292 °F). The process gives gaseous sulfur dioxide and the molybdenum(VI) oxide:[21]

The resulting oxide is then usually extracted with aqueous ammonia to give ammonium molybdate:

Copper, an impurity in molybdenite, is separated at this stage by treatment with hydrogen sulfide.[21] Ammonium molybdate converts to ammonium dimolybdate, which is isolated as a solid. Heating this solid gives molybdenum trioxide:[49]

Crude trioxide can be further purified by sublimation at 1,100 °C (2,010 °F).

Metallic molybdenum is produced by reduction of the oxide with hydrogen:

The molybdenum for steel production is reduced by the aluminothermic reaction with addition of iron to produce ferromolybdenum. A common form of ferromolybdenum contains 60% molybdenum.[21][50]

Molybdenum had a value of approximately $30,000 per tonne as of August 2009. It maintained a price at or near $10,000 per tonne from 1997 through 2003, and reached a peak of $103,000 per tonne in June 2005.[51] In 2008, the London Metal Exchange announced that molybdenum would be traded as a commodity.[52]

Mining[edit]

Historically, the Knaben mine in southern Norway, opened in 1885, was the first dedicated molybdenum mine. It was closed in 1973 but was reopened in 2007.[53] and now produces 100,000 kilograms (98 long tons; 110 short tons) of molybdenum disulfide per year. Large mines in Colorado (such as the Henderson mine and the Climax mine)[54] and in British Columbia yield molybdenite as their primary product, while many porphyry copper deposits such as the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah and the Chuquicamata mine in northern Chile produce molybdenum as a byproduct of copper mining.

Applications[edit]

Alloys[edit]

A plate of molybdenum copper alloy

About 86% of molybdenum produced is used in metallurgy, with the rest used in chemical applications. The estimated global use is structural steel 35%, stainless steel 25%, chemicals 14%, tool & high-speed steels 9%, cast iron 6%, molybdenum elemental metal 6%, and superalloys 5%.[55]

Molybdenum can withstand extreme temperatures without significantly expanding or softening, making it useful in environments of intense heat, including military armor, aircraft parts, electrical contacts, industrial motors, and supports for filaments in light bulbs.[13][56]

Most high-strength steel alloys (for example, 41xx steels) contain 0.25% to 8% molybdenum.[6] Even in these small portions, more than 43,000 tonnes of molybdenum are used each year in stainless steels, tool steels, cast irons, and high-temperature superalloys.[46]

Molybdenum is also valued in steel alloys for its high corrosion resistance and weldability.[46][48] Molybdenum contributes corrosion resistance to type-300 stainless steels (specifically type-316) and especially so in the so-called superaustenitic stainless steels (such as alloy AL-6XN, 254SMO and 1925hMo). Molybdenum increases lattice strain, thus increasing the energy required to dissolve iron atoms from the surface.[contradictory] Molybdenum is also used to enhance the corrosion resistance of ferritic (for example grade 444) and martensitic (for example 1.4122 and 1.4418) stainless steels.[citation needed]

Because of its lower density and more stable price, molybdenum is sometimes used in place of tungsten.[46] An example is the ‘M’ series of high-speed steels such as M2, M4 and M42 as substitution for the ‘T’ steel series, which contain tungsten. Molybdenum can also be used as a flame-resistant coating for other metals. Although its melting point is 2,623 °C (4,753 °F), molybdenum rapidly oxidizes at temperatures above 760 °C (1,400 °F) making it better-suited for use in vacuum environments.[56]

TZM (Mo (~99%), Ti (~0.5%), Zr (~0.08%) and some C) is a corrosion-resisting molybdenum superalloy that resists molten fluoride salts at temperatures above 1,300 °C (2,370 °F). It has about twice the strength of pure Mo, and is more ductile and more weldable, yet in tests it resisted corrosion of a standard eutectic salt (FLiBe) and salt vapors used in molten salt reactors for 1100 hours with so little corrosion that it was difficult to measure.[57][58]

Other molybdenum-based alloys that do not contain iron have only limited applications. For example, because of its resistance to molten zinc, both pure molybdenum and molybdenum-tungsten alloys (70%/30%) are used for piping, stirrers and pump impellers that come into contact with molten zinc.[59]

Other applications as a pure element[edit]

- Molybdenum powder is used as a fertilizer for some plants, such as cauliflower[46]

- Elemental molybdenum is used in NO, NO2, NOx analyzers in power plants for pollution controls. At 350 °C (662 °F), the element acts as a catalyst for NO2/NOx to form NO molecules for detection by infrared light.[60]

- Molybdenum anodes replace tungsten in certain low voltage X-ray sources for specialized uses such as mammography.[61]

- The radioactive isotope molybdenum-99 is used to generate technetium-99m, used for medical imaging[62] The isotope is handled and stored as the molybdate.[63]

Compounds[edit]

- Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is used as a solid lubricant and a high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) anti-wear agent. It forms strong films on metallic surfaces and is a common additive to HPHT greases — in the event of a catastrophic grease failure, a thin layer of molybdenum prevents contact of the lubricated parts.[64]

- When combined with small amounts of cobalt, MoS2 is also used as a catalyst in the hydrodesulfurization (HDS) of petroleum. In the presence of hydrogen, this catalyst facilitates the removal of nitrogen and especiallly sulfur from the feedstock, which otherwise would poison downstream catalysts. HDS is one of the largest scale applications of catalysis in industry.[65]

- Molybdenum oxides are important catalysts for selective oxidation of organic compounds. The production of the commodity chemicals acrylonitrile and formaldehyde relies on MoOx-based catalysts.[49]

- Molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) is an electrically conducting ceramic with primary use in heating elements operating at temperatures above 1500 °C in air.[66]

- Molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) is used as an adhesive between enamels and metals.[35]

- Lead molybdate (wulfenite) co-precipitated with lead chromate and lead sulfate is a bright-orange pigment used with ceramics and plastics.[67]

- The molybdenum-based mixed oxides are versatile catalysts in the chemical industry. Some examples are the catalysts for the oxidation of carbon monoxide, propylene to acrolein and acrylic acid, the ammoxidation of propylene to acrylonitrile.[68][69]

- Molybdenum carbides, nitride and phosphides can be used for hydrotreatment of rapeseed oil.[70]

- Ammonium heptamolybdate is used in biological staining.

- Molybdenum coated soda lime glass is used in CIGS (copper indium gallium selenide) solar cells, called CIGS solar cells.

- Phosphomolybdic acid is a stain used in thin-layer chromatography.

Biological role[edit]

Mo-containing enzymes[edit]

Molybdenum is an essential element in most organisms; a 2008 research paper speculated that a scarcity of molybdenum in the Earth’s early oceans may have strongly influenced the evolution of eukaryotic life (which includes all plants and animals).[71]

At least 50 molybdenum-containing enzymes have been identified, mostly in bacteria.[72][73] Those enzymes include aldehyde oxidase, sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase.[13] With one exception, Mo in proteins is bound by molybdopterin to give the molybdenum cofactor. The only known exception is nitrogenase, which uses the FeMoco cofactor, which has the formula Fe7MoS9C.[74]

In terms of function, molybdoenzymes catalyze the oxidation and sometimes reduction of certain small molecules in the process of regulating nitrogen, sulfur, and carbon.[75] In some animals, and in humans, the oxidation of xanthine to uric acid, a process of purine catabolism, is catalyzed by xanthine oxidase, a molybdenum-containing enzyme. The activity of xanthine oxidase is directly proportional to the amount of molybdenum in the body. An extremely high concentration of molybdenum reverses the trend and can inhibit purine catabolism and other processes. Molybdenum concentration also affects protein synthesis, metabolism, and growth.[76]

Mo is a component in most nitrogenases. Among molybdoenzymes, nitrogenases are unique in lacking the molybdopterin.[77][78] Nitrogenases catalyze the production of ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen:

The biosynthesis of the FeMoco active site is highly complex.[79]

The molybdenum cofactor (pictured) is composed of a molybdenum-free organic complex called molybdopterin, which has bound an oxidized molybdenum(VI) atom through adjacent sulfur (or occasionally selenium) atoms. Except for the ancient nitrogenases, all known Mo-using enzymes use this cofactor.

Molybdate is transported in the body as MoO42−.[76]

Human metabolism and deficiency[edit]

Molybdenum is an essential trace dietary element.[80] Four mammalian Mo-dependent enzymes are known, all of them harboring a pterin-based molybdenum cofactor (Moco) in their active site: sulfite oxidase, xanthine oxidoreductase, aldehyde oxidase, and mitochondrial amidoxime reductase.[81] People severely deficient in molybdenum have poorly functioning sulfite oxidase and are prone to toxic reactions to sulfites in foods.[82][83] The human body contains about 0.07 mg of molybdenum per kilogram of body weight,[84] with higher concentrations in the liver and kidneys and lower in the vertebrae.[46] Molybdenum is also present within human tooth enamel and may help prevent its decay.[85]

Acute toxicity has not been seen in humans, and the toxicity depends strongly on the chemical state. Studies on rats show a median lethal dose (LD50) as low as 180 mg/kg for some Mo compounds.[86] Although human toxicity data is unavailable, animal studies have shown that chronic ingestion of more than 10 mg/day of molybdenum can cause diarrhea, growth retardation, infertility, low birth weight, and gout; it can also affect the lungs, kidneys, and liver.[87][88] Sodium tungstate is a competitive inhibitor of molybdenum. Dietary tungsten reduces the concentration of molybdenum in tissues.[46]

Low soil concentration of molybdenum in a geographical band from northern China to Iran results in a general dietary molybdenum deficiency and is associated with increased rates of esophageal cancer.[89][90][91] Compared to the United States, which has a greater supply of molybdenum in the soil, people living in those areas have about 16 times greater risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.[92]

Molybdenum deficiency has also been reported as a consequence of non-molybdenum supplemented total parenteral nutrition (complete intravenous feeding) for long periods of time. It results in high blood levels of sulfite and urate, in much the same way as molybdenum cofactor deficiency. Since pure molybdenum deficiency from this cause occurs primarily in adults, the neurological consequences are not as marked as in cases of congenital cofactor deficiency.[93]

A congenital molybdenum cofactor deficiency disease, seen in infants, is an inability to synthesize molybdenum cofactor, the heterocyclic molecule discussed above that binds molybdenum at the active site in all known human enzymes that use molybdenum. The resulting deficiency results in high levels of sulfite and urate, and neurological damage.[94][95]

Excretion[edit]

Most molybdenum is excreted from the human body as molybdate in the urine. Furthermore, urinary excretion of molybdenum increases as dietary molybdenum intake increases. Small amounts of molybdenum are excreted from the body in the feces by way of the bile; small amounts also can be lost in sweat and in hair.[96][97]

Excess and copper antagonism[edit]

High levels of molybdenum can interfere with the body’s uptake of copper, producing copper deficiency. Molybdenum prevents plasma proteins from binding to copper, and it also increases the amount of copper that is excreted in urine. Ruminants that consume high levels of molybdenum suffer from diarrhea, stunted growth, anemia, and achromotrichia (loss of fur pigment). These symptoms can be alleviated by copper supplements, either dietary and injection.[98] The effective copper deficiency can be aggravated by excess sulfur.[46][99]

Copper reduction or deficiency can also be deliberately induced for therapeutic purposes by the compound ammonium tetrathiomolybdate, in which the bright red anion tetrathiomolybdate is the copper-chelating agent. Tetrathiomolybdate was first used therapeutically in the treatment of copper toxicosis in animals. It was then introduced as a treatment in Wilson’s disease, a hereditary copper metabolism disorder in humans; it acts both by competing with copper absorption in the bowel and by increasing excretion. It has also been found to have an inhibitory effect on angiogenesis, potentially by inhibiting the membrane translocation process that is dependent on copper ions.[100] This is a promising avenue for investigation of treatments for cancer, age-related macular degeneration, and other diseases that involve a pathologic proliferation of blood vessels.[101][102]

In some grazing livestock, most strongly in cattle, molybdenum excess in the soil of pasturage can produce scours (diarrhea) if the pH of the soil is neutral to alkaline; see teartness.

Dietary recommendations[edit]

In 2000, the then U.S. Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine, NAM) updated its Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for molybdenum. If there is not sufficient information to establish EARs and RDAs, an estimate designated Adequate Intake (AI) is used instead.

An AI of 2 micrograms (μg) of molybdenum per day was established for infants up to 6 months of age, and 3 μg/day from 7 to 12 months of age, both for males and females. For older children and adults, the following daily RDAs have been established for molybdenum: 17 μg from 1 to 3 years of age, 22 μg from 4 to 8 years, 34 μg from 9 to 13 years, 43 μg from 14 to 18 years, and 45 μg for persons 19 years old and older. All these RDAs are valid for both sexes. Pregnant or lactating females from 14 to 50 years of age have a higher daily RDA of 50 μg of molybdenum.

As for safety, the NAM sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of molybdenum, the UL is 2000 μg/day. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).[103]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL defined the same as in United States. For women and men ages 15 and older the AI is set at 65 μg/day. Pregnant and lactating women have the same AI. For children aged 1–14 years, the AIs increase with age from 15 to 45 μg/day. The adult AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs,[104] but on the other hand, the European Food Safety Authority reviewed the same safety question and set its UL at 600 μg/day, which is much lower than the U.S. value.[105]

Labeling[edit]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For molybdenum labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 75 μg, but as of May 27, 2016 it was revised to 45 μg.[106][107] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Food sources[edit]

Average daily intake varies between 120 and 240 μg/day, which is higher than dietary recommendations.[87] Pork, lamb, and beef liver each have approximately 1.5 parts per million of molybdenum. Other significant dietary sources include green beans, eggs, sunflower seeds, wheat flour, lentils, cucumbers, and cereal grain.[13]

Precautions[edit]

Molybdenum dusts and fumes, generated by mining or metalworking, can be toxic, especially if ingested (including dust trapped in the sinuses and later swallowed).[86] Low levels of prolonged exposure can cause irritation to the eyes and skin. Direct inhalation or ingestion of molybdenum and its oxides should be avoided.[108][109] OSHA regulations specify the maximum permissible molybdenum exposure in an 8-hour day as 5 mg/m3. Chronic exposure to 60 to 600 mg/m3 can cause symptoms including fatigue, headaches and joint pains.[110] At levels of 5000 mg/m3, molybdenum is immediately dangerous to life and health.[111]

See also[edit]

- List of molybdenum mines

- Molybdenum mining in the United States

References[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Molybdenum». CIAAW. 2013.

- ^ «Molybdenum: molybdenum(I) fluoride compound data». OpenMOPAC.net. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ Lindemann, A.; Blumm, J. (2009). Measurement of the Thermophysical Properties of Pure Molybdenum. Vol. 3. 17th Plansee Seminar.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ a b c d Lide, David R., ed. (1994). «Molybdenum». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 4. Chemical Rubber Publishing Company. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8493-0474-3.

- ^ «It’s Elemental — The Element Molybdenum». education.jlab.org. Archived from the original on 2018-07-04. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ Bjornsson, Ragnar; Neese, Frank; Schrock, Richard R.; Einsle, Oliver; DeBeer, Serena (2015). «The discovery of Mo(III) in FeMoco: reuniting enzyme and model chemistry». Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 20 (2): 447–460. doi:10.1007/s00775-014-1230-6. ISSN 0949-8257. PMC 4334110. PMID 25549604.

- ^ Van Stappen, Casey; Davydov, Roman; Yang, Zhi-Yong; Fan, Ruixi; Guo, Yisong; Bill, Eckhard; Seefeldt, Lance C.; Hoffman, Brian M.; DeBeer, Serena (2019-09-16). «Spectroscopic Description of the E1 State of Mo Nitrogenase Based on Mo and Fe X-ray Absorption and Mössbauer Studies». Inorganic Chemistry. 58 (18): 12365–12376. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01951. ISSN 0020-1669. PMC 6751781. PMID 31441651.

- ^ Leimkühler, Silke (2020). «The biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactors in Escherichia coli». Environmental Microbiology. 22 (6): 2007–2026. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15003. ISSN 1462-2920. PMID 32239579.

- ^ Wieser, M. E.; Berglund, M. (2009). «Atomic weights of the elements 2007 (IUPAC Technical Report)» (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 81 (11): 2131–2156. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-09-08-03. S2CID 98084907. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ^ Meija, Juris; et al. (2013). «Current Table of Standard Atomic Weights in Alphabetical Order: Standard Atomic weights of the elements». Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights. Archived from the original on 2014-04-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Emsley, John (2001). Nature’s Building Blocks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 262–266. ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- ^ Parish, R. V. (1977). The Metallic Elements. New York: Longman. pp. 112, 133. ISBN 978-0-582-44278-8.

- ^ Merino, Gabriel; Donald, Kelling J.; D’Acchioli, Jason S.; Hoffmann, Roald (2007). «The Many Ways To Have a Quintuple Bond». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (49): 15295–15302. doi:10.1021/ja075454b. PMID 18004851.

- ^ Roos, Björn O.; Borin, Antonio C.; Laura Gagliardi (2007). «Reaching the Maximum Multiplicity of the Covalent Chemical Bond». Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (9): 1469–72. doi:10.1002/anie.200603600. PMID 17225237.

- ^ Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 11. CRC. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ Armstrong, John T. (2003). «Technetium». Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ Wolterbeek, Hubert Theodoor; Bode, Peter «A process for the production of no-carrier added 99Mo». European Patent EP2301041 (A1) ― 2011-03-30. Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1096–1104. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Schmidt, Max (1968). «VI. Nebengruppe». Anorganische Chemie II (in German). Wissenschaftsverlag. pp. 119–127.

- ^ Werner, Helmut (2008-12-16). Landmarks in Organo-Transition Metal Chemistry: A Personal View. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-09848-7.

- ^ Pope, Michael T.; Müller, Achim (1997). «Polyoxometalate Chemistry: An Old Field with New Dimensions in Several Disciplines». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 30: 34–48. doi:10.1002/anie.199100341.

- ^ Nollet, Leo M. L., ed. (2000). Handbook of water analysis. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. pp. 280–288. ISBN 978-0-8247-8433-1.

- ^ Tamadon, Farhad; Seppelt, Konrad (2013-01-07). «The Elusive Halides VCl 5 , MoCl 6 , and ReCl 6». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (2): 767–769. doi:10.1002/anie.201207552. PMID 23172658.

- ^ Walton, Richard A.; Fanwick, Phillip E.; Girolami, Gregory S.; Murillo, Carlos A.; Johnstone, Erik V. (2014). Girolami, Gregory S.; Sattelberger, Alfred P. (eds.). Inorganic Syntheses: Volume 36. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 78–81. doi:10.1002/9781118744994.ch16. ISBN 9781118744994.

- ^ Drago, R. S. , Long, J. R., and Cosmano, R. (1982) Comparison of the Coordination Chemistry and inductive Transfer through the Metal-Metal Bond in Adducts of Dirhodium and Dimolybdenum Carboxylates . Inorganic Chemistry 21, 2196-2201.

- ^ Werner, Helmut (2008-12-16). Landmarks in Organo-Transition Metal Chemistry: A Personal View. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-09848-7.

- ^ Lansdown, A. R. (1999). Molybdenum disulphide lubrication. Tribology and Interface Engineering. Vol. 35. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-50032-8.

- ^ Melchert, Craig. «Greek mólybdos as a Loanword from Lydian» (PDF). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ International Molybdenum Association, «Molybdenum History»

- ^ Institute, American Iron and Steel (1948). Accidental use of molybdenum in old sword led to new alloy.

- ^ Van der Krogt, Peter (2006-01-10). «Molybdenum». Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ a b Gagnon, Steve. «Molybdenum». Jefferson Science Associates, LLC. Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Scheele, C. W. K. (1779). «Versuche mit Wasserbley;Molybdaena». Svenska Vetensk. Academ. Handlingar. 40: 238.

- ^ Hjelm, P. J. (1788). «Versuche mit Molybdäna, und Reduction der selben Erde». Svenska Vetensk. Academ. Handlingar. 49: 268.

- ^ Hoyt, Samuel Leslie (1921). Metallography. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Krupp, Alfred; Wildberger, Andreas (1888). The metallic alloys: A practical guide for the manufacture of all kinds of alloys, amalgams, and solders, used by metal-workers … with an appendix on the coloring of alloys. H.C. Baird & Co. p. 60.

- ^ Gupta, C. K. (1992). Extractive Metallurgy of Molybdenum. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4758-0.

- ^ Reich, Leonard S. (2002-08-22). The Making of American Industrial Research: Science and Business at Ge and Bell, 1876–1926. p. 117. ISBN 9780521522373. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ^ Vokes, Frank Marcus (1963). Molybdenum deposits of Canada. p. 3.

- ^ Chemical properties of molibdenum — Health effects of molybdenum — Environmental effects of molybdenum Archived 2016-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. lenntech.com

- ^ Sam Kean. The Disappearing Spoon. Page 88–89

- ^ Millholland, Ray (August 1941). «Battle of the Billions: American industry mobilizes machines, materials, and men for a job as big as digging 40 Panama Canals in one year». Popular Science: 61. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Considine, Glenn D., ed. (2005). «Molybdenum». Van Nostrand’s Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York: Wiley-Interscience. pp. 1038–1040. ISBN 978-0-471-61525-5.

- ^ Jambor, J.L.; et al. (2002). «New mineral names» (PDF). American Mineralogist. 87: 181. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ^ a b «Molybdenum Statistics and Information». U.S. Geological Survey. 2007-05-10. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ a b Sebenik, Roger F.; Burkin, A. Richard; Dorfler, Robert R.; Laferty, John M.; Leichtfried, Gerhard; Meyer-Grünow, Hartmut; Mitchell, Philip C. H.; Vukasovich, Mark S.; Church, Douglas A.; Van Riper, Gary G.; Gilliland, James C.; Thielke, Stanley A. (2000). «Molybdenum and Molybdenum Compounds». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_655. ISBN 3527306730. S2CID 98762721.

- ^ Gupta, C. K. (1992). Extractive Metallurgy of Molybdenum. CRC Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-8493-4758-0.

- ^ «Dynamic Prices and Charts for Molybdenum». InfoMine Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ «LME to launch minor metals contracts in H2 2009». London Metal Exchange. 2008-09-04. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Langedal, M. (1997). «Dispersion of tailings in the Knabena—Kvina drainage basin, Norway, 1: Evaluation of overbank sediments as sampling medium for regional geochemical mapping». Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 58 (2–3): 157–172. doi:10.1016/S0375-6742(96)00069-6.

- ^ Coffman, Paul B. (1937). «The Rise of a New Metal: The Growth and Success of the Climax Molybdenum Company». The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago. 10: 30. doi:10.1086/232443.

- ^ Pie chart of world Mo uses. London Metal Exchange.

- ^ a b «Molybdenum». AZoM.com Pty. Limited. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Smallwood, Robert E. (1984). «TZM Moly Alloy». ASTM special technical publication 849: Refractory metals and their industrial applications: a symposium. ASTM International. p. 9. ISBN 9780803102033.

- ^ «Compatibility of Molybdenum-Base Alloy TZM, with LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4«. Oak Ridge National Laboratory Report. December 1969. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ Cubberly, W. H.; Bakerjian, Ramon (1989). Tool and manufacturing engineers handbook. Society of Manufacturing Engineers. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-87263-351-3.

- ^ Lal, S.; Patil, R. S. (2001). «Monitoring of atmospheric behaviour of NOx from vehicular traffic». Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 68 (1): 37–50. doi:10.1023/A:1010730821844. PMID 11336410. S2CID 20441999.

- ^ Lancaster, Jack L. «Ch. 4: Physical determinants of contrast» (PDF). Physics of Medical X-Ray Imaging. University of Texas Health Science Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-10.

- ^ Gray, Theodore (2009). The Elements. Black Dog & Leventhal. pp. 105–107. ISBN 1-57912-814-9.

- ^ Gottschalk, A. (1969). «Technetium-99m in clinical nuclear medicine». Annual Review of Medicine. 20 (1): 131–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.20.020169.001023. PMID 4894500.

- ^ Winer, W. (1967). «Molybdenum disulfide as a lubricant: A review of the fundamental knowledge» (PDF). Wear. 10 (6): 422–452. doi:10.1016/0043-1648(67)90187-1. hdl:2027.42/33266.

- ^ Topsøe, H.; Clausen, B. S.; Massoth, F. E. (1996). Hydrotreating Catalysis, Science and Technology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Moulson, A. J.; Herbert, J. M. (2003). Electroceramics: materials, properties, applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-471-49748-6.

- ^ International Molybdenum Association Archived 2008-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. imoa.info.

- ^ Fierro, J. G. L., ed. (2006). Metal Oxides, Chemistry and Applications. CRC Press. pp. 414–455.

- ^ Centi, G.; Cavani, F.; Trifiro, F. (2001). Selective Oxidation by Heterogeneous Catalysis. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 363–384.

- ^ Horáček, Jan; Akhmetzyanova, Uliana; Skuhrovcová, Lenka; Tišler, Zdeněk; de Paz Carmona, Héctor (1 April 2020). «Alumina-supported MoNx, MoCx and MoPx catalysts for the hydrotreatment of rapeseed oil». Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 263: 118328. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118328. ISSN 0926-3373. S2CID 208758175.

- ^ Scott, C.; Lyons, T. W.; Bekker, A.; Shen, Y.; Poulton, S. W.; Chu, X.; Anbar, A. D. (2008). «Tracing the stepwise oxygenation of the Proterozoic ocean». Nature. 452 (7186): 456–460. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..456S. doi:10.1038/nature06811. PMID 18368114. S2CID 205212619.

- ^ Enemark, John H.; Cooney, J. Jon A.; Wang, Jun-Jieh; Holm, R. H. (2004). «Synthetic Analogues and Reaction Systems Relevant to the Molybdenum and Tungsten Oxotransferases». Chem. Rev. 104 (2): 1175–1200. doi:10.1021/cr020609d. PMID 14871153.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R.; Bittner, Florian (2006). «Cell biology of molybdenum». Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) — Molecular Cell Research. 1763 (7): 621–635. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.013. PMID 16784786.

- ^ Russ Hille; James Hall; Partha Basu (2014). «The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes». Chem. Rev. 114 (7): 3963–4038. doi:10.1021/cr400443z. PMC 4080432. PMID 24467397.

- ^ Kisker, C.; Schindelin, H.; Baas, D.; Rétey, J.; Meckenstock, R. U.; Kroneck, P. M. H. (1999). «A structural comparison of molybdenum cofactor-containing enzymes» (PDF). FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22 (5): 503–521. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00384.x. PMID 9990727. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Phillip C. H. (2003). «Overview of Environment Database». International Molybdenum Association. Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R. (2013). «Chapter 15 Metabolism of Molybdenum». In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_15 (inactive 31 December 2022). ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2022 (link) electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402 - ^

Chi Chung, Lee; Markus W., Ribbe; Yilin, Hu (2014). «Chapter 7. Cleaving the N,N Triple Bond: The Transformation of Dinitrogen to Ammonia by Nitrogenases«. In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 147–174. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_6. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416393. - ^ Dos Santos, Patricia C.; Dean, Dennis R. (2008). «A newly discovered role for iron-sulfur clusters». PNAS. 105 (33): 11589–11590. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511589D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805713105. PMC 2575256. PMID 18697949.

- ^ Schwarz, Guenter; Belaidi, Abdel A. (2013). «Chapter 13. Molybdenum in Human Health and Disease». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 415–450. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_13. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470099.

- ^ Mendel, Ralf R. (2009). «Cell biology of molybdenum». BioFactors. 35 (5): 429–34. doi:10.1002/biof.55. PMID 19623604. S2CID 205487570.

- ^ Blaylock Wellness Report, February 2010, page 3.

- ^ Cohen, H. J.; Drew, R. T.; Johnson, J. L.; Rajagopalan, K. V. (1973). «Molecular Basis of the Biological Function of Molybdenum. The Relationship between Sulfite Oxidase and the Acute Toxicity of Bisulfite and SO2«. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 70 (12 Pt 1–2): 3655–3659. Bibcode:1973PNAS…70.3655C. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3655. PMC 427300. PMID 4519654.

- ^ Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. p. 1384. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Curzon, M. E. J.; Kubota, J.; Bibby, B. G. (1971). «Environmental Effects of Molybdenum on Caries». Journal of Dental Research. 50 (1): 74–77. doi:10.1177/00220345710500013401. S2CID 72386871.

- ^ a b «Risk Assessment Information System: Toxicity Summary for Molybdenum». Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ a b Coughlan, M. P. (1983). «The role of molybdenum in human biology». Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 6 (S1): 70–77. doi:10.1007/BF01811327. PMID 6312191. S2CID 10114173.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G.; Barceloux, Donald (1999). «Molybdenum». Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 231–237. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102422. PMID 10382558.

- ^ Yang, Chung S. (1980). «Research on Esophageal Cancer in China: a Review» (PDF). Cancer Research. 40 (8 Pt 1): 2633–44. PMID 6992989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Nouri, Mohsen; Chalian, Hamid; Bahman, Atiyeh; Mollahajian, Hamid; et al. (2008). «Nail Molybdenum and Zinc Contents in Populations with Low and Moderate Incidence of Esophageal Cancer» (PDF). Archives of Iranian Medicine. 11 (4): 392–6. PMID 18588371. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ Zheng, Liu; et al. (1982). «Geographical distribution of trace elements-deficient soils in China». Acta Ped. Sin. 19: 209–223.

- ^ Taylor, Philip R.; Li, Bing; Dawsey, Sanford M.; Li, Jun-Yao; Yang, Chung S.; Guo, Wande; Blot, William J. (1994). «Prevention of Esophageal Cancer: The Nutrition Intervention Trials in Linxian, China» (PDF). Cancer Research. 54 (7 Suppl): 2029s–2031s. PMID 8137333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ^ Abumrad, N. N. (1984). «Molybdenum—is it an essential trace metal?». Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 60 (2): 163–71. PMC 1911702. PMID 6426561.

- ^ Smolinsky, B; Eichler, S. A.; Buchmeier, S.; Meier, J. C.; Schwarz, G. (2008). «Splice-specific Functions of Gephyrin in Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis». Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (25): 17370–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800985200. PMID 18411266.

- ^ Reiss, J. (2000). «Genetics of molybdenum cofactor deficiency». Human Genetics. 106 (2): 157–63. doi:10.1007/s004390051023. PMID 10746556.

- ^ Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.; Carr, Timothy P. (2016-10-05). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-337-51421-7.

- ^ Turnlund, J. R.; Keyes, W. R.; Peiffer, G. L. (October 1995). «Molybdenum absorption, excretion, and retention studied with stable isotopes in young men at five intakes of dietary molybdenum». The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 62 (4): 790–796. doi:10.1093/ajcn/62.4.790. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 7572711.

- ^ Suttle, N. F. (1974). «Recent studies of the copper-molybdenum antagonism». Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 33 (3): 299–305. doi:10.1079/PNS19740053. PMID 4617883.

- ^ Hauer, Gerald Copper deficiency in cattle Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Bison Producers of Alberta. Accessed Dec. 16, 2010.

- ^ Nickel, W (2003). «The Mystery of nonclassical protein secretion, a current view on cargo proteins and potential export routes». Eur. J. Biochem. 270 (10): 2109–2119. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03577.x. PMID 12752430.

- ^ Brewer GJ; Hedera, P.; Kluin, K. J.; Carlson, M.; Askari, F.; Dick, R. B.; Sitterly, J.; Fink, J. K. (2003). «Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate: III. Initial therapy in a total of 55 neurologically affected patients and follow-up with zinc therapy». Arch Neurol. 60 (3): 379–85. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.3.379. PMID 12633149.

- ^ Brewer, G. J.; Dick, R. D.; Grover, D. K.; Leclaire, V.; Tseng, M.; Wicha, M.; Pienta, K.; Redman, B. G.; Jahan, T.; Sondak, V. K.; Strawderman, M.; LeCarpentier, G.; Merajver, S. D. (2000). «Treatment of metastatic cancer with tetrathiomolybdate, an anticopper, antiangiogenic agent: Phase I study». Clinical Cancer Research. 6 (1): 1–10. PMID 10656425.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2000). «Molybdenum». Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 420–441. doi:10.17226/10026. ISBN 978-0-309-07279-3. PMID 25057538. S2CID 44243659.

- ^ «Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies» (PDF). 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-16, retrieved 2017-09-10

- ^ «Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ «Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)». Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «Material Safety Data Sheet – Molybdenum». The REMBAR Company, Inc. 2000-09-19. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ «Material Safety Data Sheet – Molybdenum Powder». CERAC, Inc. 1994-02-23. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ «NIOSH Documentation for IDLHs Molybdenum». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 1996-08-16. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ «CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Molybdenum». www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

Bibliography[edit]

- Lettera di Giulio Candida al signor Vincenzo Petagna — Sulla formazione del molibdeno. Naples: Giuseppe Maria Porcelli. 1785.

External links[edit]

![]()

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Molybdenum.

![]()

Look up molybdenum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Molybdenum at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Mineral & Exploration – Map of World Molybdenum Producers 2009

- «Mining A Mountain» Popular Mechanics, July 1935 pp. 63–64

- Site for global molybdenum info

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

| Molybdenum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (mə-LIB-də-nəm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mo) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molybdenum in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 42 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d5 5s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 13, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2896 K (2623 °C, 4753 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 4912 K (4639 °C, 8382 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 10.28 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 9.33 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 37.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 598 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.06 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4, −2, −1, 0, +1,[2] +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 139 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 154±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of molybdenum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5400 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 4.8 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 138 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal diffusivity | 54.3 mm2/s (at 300 K)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 53.4 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +89.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 329 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 126 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 230 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1400–2740 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 1370–2500 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-98-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1778) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Peter Jacob Hjelm (1781) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of molybdenum

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin molybdaenum, which is based on Ancient Greek Μόλυβδος molybdos, meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores.[6] Molybdenum minerals have been known throughout history, but the element was discovered (in the sense of differentiating it as a new entity from the mineral salts of other metals) in 1778 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele. The metal was first isolated in 1781 by Peter Jacob Hjelm.[7]

Molybdenum does not occur naturally as a free metal on Earth; it is found only in various oxidation states in minerals. The free element, a silvery metal with a grey cast, has the sixth-highest melting point of any element. It readily forms hard, stable carbides in alloys, and for this reason most of the world production of the element (about 80%) is used in steel alloys, including high-strength alloys and superalloys.

Most molybdenum compounds have low solubility in water, but when molybdenum-bearing minerals contact oxygen and water, the resulting molybdate ion MoO2−

4 is quite soluble. Industrially, molybdenum compounds (about 14% of world production of the element) are used in high-pressure and high-temperature applications as pigments and catalysts.

Molybdenum-bearing enzymes are by far the most common bacterial catalysts for breaking the chemical bond in atmospheric molecular nitrogen in the process of biological nitrogen fixation. At least 50 molybdenum enzymes are now known in bacteria, plants, and animals, although only bacterial and cyanobacterial enzymes are involved in nitrogen fixation. These nitrogenases contain an iron-molybdenum cofactor FeMoco, which is believed to contain either Mo(III) or Mo(IV).[8][9] This is distinct from the fully oxidized Mo(VI) found complexed with molybdopterin in all other molybdenum-bearing enzymes, which perform a variety of crucial functions.[10] The variety of crucial reactions catalyzed by these latter enzymes means that molybdenum is an essential element for all higher eukaryote organisms, including humans.

Characteristics[edit]

Physical properties[edit]

In its pure form, molybdenum is a silvery-grey metal with a Mohs hardness of 5.5 and a standard atomic weight of 95.95 g/mol.[11][12] It has a melting point of 2,623 °C (4,753 °F); of the naturally occurring elements, only tantalum, osmium, rhenium, tungsten, and carbon have higher melting points.[6] It has one of the lowest coefficients of thermal expansion among commercially used metals.[13]

Chemical properties[edit]

Molybdenum is a transition metal with an electronegativity of 2.16 on the Pauling scale. It does not visibly react with oxygen or water at room temperature. Weak oxidation of molybdenum starts at 300 °C (572 °F); bulk oxidation occurs at temperatures above 600 °C, resulting in molybdenum trioxide. Like many heavier transition metals, molybdenum shows little inclination to form a cation in aqueous solution, although the Mo3+ cation is known under carefully controlled conditions.[14]

Gaseous molybdenum consists of the diatomic species Mo2. That molecule is a singlet, with two unpaired electrons in bonding orbitals, in addition to 5 conventional bonds. The result is a sextuple bond.[15][16]

Isotopes[edit]

There are 35 known isotopes of molybdenum, ranging in atomic mass from 83 to 117, as well as four metastable nuclear isomers. Seven isotopes occur naturally, with atomic masses of 92, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, and 100. Of these naturally occurring isotopes, only molybdenum-100 is unstable.[17]

Molybdenum-98 is the most abundant isotope, comprising 24.14% of all molybdenum. Molybdenum-100 has a half-life of about 1019 y and undergoes double beta decay into ruthenium-100. All unstable isotopes of molybdenum decay into isotopes of niobium, technetium, and ruthenium. Of the synthetic radioisotopes, the most stable is 93Mo, with a half-life of 4,000 years.[18]

The most common isotopic molybdenum application involves molybdenum-99, which is a fission product. It is a parent radioisotope to the short-lived gamma-emitting daughter radioisotope technetium-99m, a nuclear isomer used in various imaging applications in medicine.[19]

In 2008, the Delft University of Technology applied for a patent on the molybdenum-98-based production of molybdenum-99.[20]

Compounds[edit]

Molybdenum forms chemical compounds in oxidation states −IV and from −II to +VI. Higher oxidation states are more relevant to its terrestrial occurrence and its biological roles, mid-level oxidation states are often associated with metal clusters, and very low oxidation states are typically associated with organomolybdenum compounds. Mo and W chemistry shows strong similarities. The relative rarity of molybdenum(III), for example, contrasts with the pervasiveness of the chromium(III) compounds. The highest oxidation state is seen in molybdenum(VI) oxide (MoO3), whereas the normal sulfur compound is molybdenum disulfide MoS2.[21]

| Oxidation state | Example[22][23] |

|---|---|

| −4 | Na 4[Mo(CO) 4] |

| −1 | Na 2[Mo 2(CO) 10] |

| 0 | Mo(CO) 6 |

| +1 | Na[C 6H 6Mo] |

| +2 | MoCl 2 |

| +3 | MoBr 3 |

| +4 | MoS 2 |

| +5 | MoCl 5 |

| +6 | MoF 6 |

From the perspective of commerce, the most important compounds are molybdenum disulfide (MoS

2) and molybdenum trioxide (MoO

3). The black disulfide is the main mineral. It is roasted in air to give the trioxide:[21]

- 2 MoS

2 + 7 O

2 → 2 MoO

3 + 4 SO

2

The trioxide, which is volatile at high temperatures, is the precursor to virtually all other Mo compounds as well as alloys. Molybdenum has several oxidation states, the most stable being +4 and +6 (bolded in the table at left).

Molybdenum(VI) oxide is soluble in strong alkaline water, forming molybdates (MoO42−). Molybdates are weaker oxidants than chromates. They tend to form structurally complex oxyanions by condensation at lower pH values, such as [Mo7O24]6− and [Mo8O26]4−. Polymolybdates can incorporate other ions, forming polyoxometalates.[24] The dark-blue phosphorus-containing heteropolymolybdate P[Mo12O40]3− is used for the spectroscopic detection of phosphorus.[25] The broad range of oxidation states of molybdenum is reflected in various molybdenum chlorides:[21]

- Molybdenum(II) chloride MoCl2, which exists as the hexamer Mo6Cl12 and the related dianion [Mo6Cl14]2-.

- Molybdenum(III) chloride MoCl3, a dark red solid, which converts to the anion trianionic complex [MoCl6]3-.

- Molybdenum(IV) chloride MoCl4, a black solid, which adopts a polymeric structure.

- Molybdenum(V) chloride MoCl5 dark green solid, which adopts a dimeric structure.

- Molybdenum(VI) chloride MoCl6 is a black solid, which is monomeric and slowly decomposes to MoCl5 and Cl2 at room temperature.[26]

Like chromium and some other transition metals, molybdenum forms quadruple bonds, such as in Mo2(CH3COO)4 and [Mo2Cl8]4−.[21][27] The Lewis acid properties of the butyrate and perfluorobutyrate dimers, Mo2(O2CR)4 and Rh2(O2CR) 4, have been reported.[28]

The oxidation state 0 and lower are possible with carbon monoxide as ligand, such as in molybdenum hexacarbonyl, Mo(CO)6.[21][29]

History[edit]

Molybdenite—the principal ore from which molybdenum is now extracted—was previously known as molybdena. Molybdena was confused with and often utilized as though it were graphite. Like graphite, molybdenite can be used to blacken a surface or as a solid lubricant.[30] Even when molybdena was distinguishable from graphite, it was still confused with the common lead ore PbS (now called galena); the name comes from Ancient Greek Μόλυβδος molybdos, meaning lead.[13] (The Greek word itself has been proposed as a loanword from Anatolian Luvian and Lydian languages).[31]

Although (reportedly) molybdenum was deliberately alloyed with steel in one 14th-century Japanese sword (mfd. ca. 1330), that art was never employed widely and was later lost.[32][33] In the West in 1754, Bengt Andersson Qvist examined a sample of molybdenite and determined that it did not contain lead and thus was not galena.[34]

By 1778 Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele stated firmly that molybdena was (indeed) neither galena nor graphite.[35][36] Instead, Scheele correctly proposed that molybdena was an ore of a distinct new element, named molybdenum for the mineral in which it resided, and from which it might be isolated. Peter Jacob Hjelm successfully isolated molybdenum using carbon and linseed oil in 1781.[13][37]