| Symphony No. 6 | |

|---|---|

| by Gustav Mahler | |

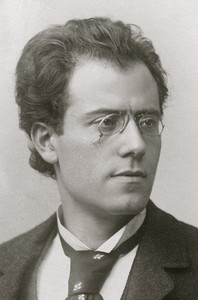

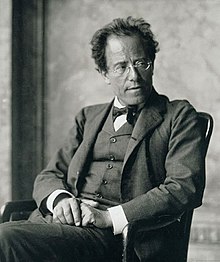

| Gustav Mahler in 1907 | |

| Key | A minor |

| Composed | 1903–1904: Maiernigg |

| Published |

|

| Recorded | F. Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony, 1952 |

| Duration | 77–85 minutes |

| Movements | 4 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 27 May 1906 |

| Location | Saalbau Essen |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

The Symphony No. 6 in A minor by Gustav Mahler is a symphony in four movements, composed in 1903 and 1904, with revisions from 1906. It is sometimes nicknamed the Tragic («Tragische»), though the origin of the name is unclear.[1]

Introduction[edit]

Mahler conducted the work’s first performance at the Saalbau concert hall in Essen on 27 May 1906. Mahler composed the symphony at an exceptionally happy time in his life, as he had married Alma Schindler in 1902, and during the course of the work’s composition his second daughter was born. This contrasts with the tragic, even nihilistic, ending of No. 6. Both Alban Berg and Anton Webern praised the work when they first heard it. In a 1908 letter to Webern, Berg said in his opinion there was just one «sixth symphony», despite that of Beethoven.[2]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for large orchestra, consisting of the following:

Contemporary caricature about the unorthodox usage of a hammer: «My god, I forgot the car horn! Now I can write another symphony.» (Die Muskete [de], 19 January 1907)

In addition to very large woodwind and brass sections, Mahler augmented the percussion section with several unusual instruments, including the famous «Mahler hammer». The sound of the hammer, which features in the last movement, was stipulated by Mahler to be «brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe).» The sound achieved in the premiere did not quite carry far enough from the stage, and indeed the problem of achieving the proper volume while still remaining dull in resonance remains a challenge to the modern orchestra. Various methods of producing the sound have involved a wooden mallet striking a wooden surface, a sledgehammer striking a wooden box, or a particularly large bass drum, or sometimes simultaneous use of more than one of these methods. Contemporaries mocked the use of the hammer, as shown by a caricature from the satirical magazine Die Muskete [de].[3]

Nickname of Tragische[edit]

The status of the symphony’s nickname is problematic.[1] Mahler did not title the symphony when he composed it, or at its first performance or first publication. When he allowed Richard Specht to analyse the work and Alexander von Zemlinsky to arrange the symphony, he did not authorize any sort of nickname for the symphony. He had, as well, decisively rejected and disavowed the titles (and programmes) of his earlier symphonies by 1900. Only the words «Sechste Sinfonie» appeared on the programme for the performance in Munich on November 8, 1906.[4]: 59 Nor does the word Tragische appear on any of the scores that C. F. Kahnt published (first edition, 1906; revised edition, 1906), in Specht’s officially approved Thematische Führer (‘thematic guide’)[4]: 50 or on Zemlinsky’s piano duet transcription (1906).[4]: 57 By contrast, in his Gustav Mahler memoir, Bruno Walter claimed that «Mahler called [the work] his Tragic Symphony«. Additionally, the programme for the first Vienna performance (January 4, 1907) refers to the work as «Sechste Sinfonie (Tragische)«.

Structure[edit]

The work is in four movements and has a duration of around 80 minutes. The order of the inner movements has been a matter of controversy. The first published edition of the score (C. F. Kahnt, 1906) featured the movements in the following order:[5]

- Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.

- Scherzo: Wuchtig

- Andante moderato

- Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico

Mahler later placed the Andante as the second movement, and this new order of the inner movements was reflected in the second and third published editions of the score, as well as the Essen premiere.

- Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.

- Andante moderato

- Scherzo: Wuchtig

- Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico

The first three movements are relatively traditional in structure and character, with a standard sonata form first movement (even including an exact repeat of the exposition, unusual in Mahler) leading to the middle movements – one a scherzo-with-trios, the other slow. However, attempts to analyze the vast finale in terms of the sonata archetype have encountered serious difficulties. As Dika Newlin has pointed out:

it has elements of what is conventionally known as ‘sonata form’, but the music does not follow a set pattern … Thus, ‘expositional’ treatment merges directly into the type of contrapuntal and modulatory writing appropriate to ‘elaboration’ sections …; the beginning of the principal theme-group is recapitulated in C minor rather than in A minor, and the C minor chorale theme … of the exposition is never recapitulated at all.[6]

I. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.[edit]

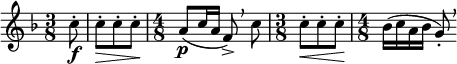

The first movement, which for the most part has the character of a march, features a motif consisting of an A major triad turning to A minor over a distinctive timpani rhythm. The chords are played by trumpets and oboes when first heard, with the trumpets sounding the loudest in the first chord and the oboes in the second.

This motif reappears in subsequent movements. The first movement also features a soaring melody which the composer’s wife, Alma Mahler, claimed represented her. This melody is often called the «Alma theme».[7] A restatement of that theme at the movement’s end marks the happiest point of the symphony.

II. Scherzo: Wuchtig[edit]

The scherzo marks a return to the unrelenting march rhythms of the first movement, though in a ‘triple-time’ metrical context.

Its trio (the middle section), marked Altväterisch (‘old-fashioned’), is rhythmically irregular (4

8 switching to 3

8 and 3

4) and of a somewhat gentler character.

According to Alma Mahler, in this movement Mahler «represented the arrhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zigzags over the sand». The chronology of its composition suggests otherwise. The movement was composed in the summer of 1903, when Maria Anna (born November 1902) was less than a year old. Anna Justine was born a year later in July 1904.[citation needed]

III. Andante moderato[edit]

Performed by the Virtual Philharmonic Orchestra (Reinhold Behringer) with digital samples

The andante provides a respite from the intensity of the rest of the work. Its main theme is an introspective ten-bar phrase in E♭ major, though it frequently touches on the minor mode as well. The orchestration is more delicate and reserved in this movement, making it all the more poignant when compared to the other three.

IV. Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico[edit]

The last movement is an extended sonata form, characterized by drastic changes in mood and tempo, the sudden change of glorious soaring melody to deep agony.

The movement is punctuated by two hammer blows. The original score had five hammer blows, which Mahler subsequently reduced to three, and eventually to two.[8][9]

Alma quoted her husband as saying that these were three mighty blows of fate befallen by the hero, «the third of which fells him like a tree». She identified these blows with three later events in Gustav Mahler’s own life: the death of his eldest daughter Maria Anna Mahler, the diagnosis of an eventually fatal heart condition, and his forced resignation from the Vienna Opera and departure from Vienna. When he revised the work, Mahler removed the last of these three hammer strokes so that the music built to a sudden moment of stillness in place of the third blow. Some recordings and performances, notably those of Leonard Bernstein, have restored the third hammer blow.[10] The piece ends with the same rhythmic motif that appeared in the first movement, but the chord above it is a simple A minor triad, rather than A major turning into A minor. After the third ‘hammer-blow’ passage, the music gropes in darkness and then the trombones and horns begin to offer consolation. However, after they turn briefly to major they fade away and the final bars erupt fff in the minor.

Order of the inner movements and performance history issue[edit]

Controversy exists over the order of the two middle movements. Mahler conceived the work as having the scherzo second and the slow movement third, a somewhat unclassical arrangement adumbrated in such earlier large-scale symphonies as Beethoven’s No. 9, Bruckner’s No. 8 and (unfinished) No. 9, and Mahler’s own four-movement No. 1 and No. 4. It was in this arrangement that the symphony was completed (in 1904) and published (in March 1906); and it was with a conducting score in which the scherzo preceded the slow movement that Mahler began rehearsals for the work’s first performance, as noted by Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange:

«Scherzo 2» was undeniably the original order, the one in which Mahler first conceived, composed, and published the Sixth Symphony, and also the one in which he rehearsed the work with two different orchestras before changing his mind at the last minute before the premiere.[11]

Alfred Roller, a close collaborator and colleague of Mahler’s in Vienna, communicated in a 2 May 1906 letter to his fiancée Mileva Stojsavljevic, on the Mahlers’ reaction to the 1 May 1906 orchestral rehearsal of the work in Vienna, in its original movement order:

Today I was there at noon, but I could not talk much with Alma, since M[ahler] was almost always there, I saw only that the two of them were very happy and satisfied…[11]

During those later May 1906 rehearsals in Essen, however, Mahler decided that the slow movement should precede the scherzo. Klaus Pringsheim, another colleague of Mahler’s at the Hofoper, reminisced in a 1920 article on the situation at the Essen rehearsals, on Mahler’s state of mind at the time:

Those close to him were well aware of Mahler’s «insecurity». Even after the final rehearsal he was still not sure whether or not he had found the right tempo for the Scherzo, and had wondered whether he should invert the order of the second and third movements (which he subsequently did).[11]

Mahler instructed his publishers Christian Friedrich Kahnt [de] to prepare a «second edition» of the work with the movements in that order, and meanwhile to insert errata slips indicating the change of order into all unsold copies of the existing edition. Mahler conducted the 27 May 1906 public premiere, and his other two subsequent performances of the Sixth Symphony, in November 1906 (Munich) and 4 January 1907 (Vienna) with his revised order of the inner movements. In the period immediately after Mahler’s death, scholars such as Paul Bekker, Ernst Decsey, Richard Specht, and Paul Stefan published studies with reference to the Sixth Symphony in Mahler’s second edition with the Andante/Scherzo order.[12]

One of the first occasions after Mahler’s death where the conductor reverted to the original movement order is in 1919/1920, after an inquiry in the autumn of 1919 from Willem Mengelberg to Alma Mahler in preparation for the May 1920 Mahler Festival in Amsterdam of the complete symphonies, regarding the order of the inner movements of the Sixth Symphony. In a telegram dated 1 October 1919, Alma responded to Mengelberg:[12]

Erst Scherzo dann Andante herzlichst Alma («First Scherzo then Andante affectionately Alma»)[12]

Mengelberg, who had been in close touch with Mahler until the latter’s death, and had conducted the symphony in the «Andante/Scherzo» arrangement up to 1916, then switched to the «Scherzo/Andante» order. In his own copy of the score, he wrote on the first page:[12]

Nach Mahlers Angabe II erst Scherzo dann III Andante («According to Mahler’s indications, first II Scherzo, then III Andante»)[11]

Other conductors, such as Oskar Fried, continued to perform (and eventually record) the work as ‘Andante/Scherzo’, per the second edition, right up to the early 1960s. Exceptions included two performances in Vienna on 14 December 1930 and 23 May 1933, conducted by Anton Webern, who utilised the Scherzo/Andante order of the inner movements. Anna Mahler, Mahler’s daughter, attended both of these performances.[11] De La Grange commented on Webern’s choice of the Scherzo/Andante order:

Anton Webern had favoured the original order of movements in the two performances he conducted in Vienna on 14 December 1930 and 23 May 1933. Webern was not only a great composer, but also one of Mahler’s earliest and most passionate devotees and a much admired conductor of Mahler’s music…it is inconceivable that he could have performed a version that would have shocked and displeased his beloved master and mentor.»[11]

In 1963, a new critical edition of the Sixth Symphony appeared, under the auspices of the Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft (IGMG) and its president, Erwin Ratz, a pupil of Webern,[11] an edition which restored Mahler’s original order of the inner movements. Ratz, however, did not offer documented support, such as Alma Mahler’s 1919 telegram, for his assertion that Mahler «changed his mind a second time» at some point before his death. In his analysis of the Sixth Symphony, Norman Del Mar argued for the Andante/Scherzo order of the inner movements,[4]: 43 [13] and criticised the Ratz edition for its lack of documentary evidence to justify the Scherzo/Andante order. In contrast, scholars such as Theodor W. Adorno, Henry-Louis de La Grange, Hans-Peter Jülg and Karl Heinz Füssl have argued for the original order as more appropriate, expostulating on the overall tonal scheme and the various relationships between the keys in the final three movements. Füssl, in particular, noted that Ratz made his decision under historical circumstances where the history of the different autographs and versions was not completely known at the time.[12] Füssl has also noted the following features of the Scherzo/Andante order:[14]

- The Scherzo is an example of ‘developing variation’ in its treatment of material from the first movement, where separation of the Scherzo from the first movement by the Andante disrupts that linkage.

- The Scherzo and the first movement use identical keys, A minor at the beginning and F major in the trio.

- The Andante’s key, E♭ major, is farthest removed from the key at the close of the first movement (A major), whilst the C minor key at the beginning of the finale acts as transition from E♭ major to A minor, the principal key of the finale.

The 1968 Eulenberg Edition of the Sixth Symphony, edited by Hans Redlich, restores most of Mahler’s original orchestration and utilises the original order of Scherzo/Andante for the order of the middle movements.[8] The most recent IGMG critical edition of the Sixth Symphony was published in 2010, under the general editorship of Reinhold Kubik, and uses the Andante/Scherzo order for the middle movements.[8] Kubik had previously declared in 2004:

- «As the current Chief Editor of the Complete Critical Edition, I declare the official position of the institution I represent is that the correct order of the middle movements of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony is Andante-Scherzo.»[4]

This statement has been criticised, in the manner of earlier criticism of Ratz, on several levels:

- for itself lacking documentary support and for expressing a personal preference based on subjective animus related to the Alma Problem, rather than any actual documentary evidence[8]

- for its blanket dismissal of the evidence of the original score with the Scherzo/Andante order[11]

- for imposing an advance bias rather than allowing musicians to arrive at their own choice independently.[8]

British composer David Matthews was a former adherent of the Andante/Scherzo order,[5] but has since changed his mind and now argues for Scherzo/Andante as the preferred order, again citing the overall tonal scheme of the symphony.[15] In keeping with Mahler’s original order, British conductor John Carewe has noted parallels between the tonal plan of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 and Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, with the Scherzo/Andante order of movements in the latter. David Matthews has noted the interconnectivity of the first movement with the Scherzo as similar to Mahler’s interconnectivity of the first two movements of the Fifth Symphony, and that performing the Mahler with the Andante/Scherzo order would damage the structure of the tonal key relationships and remove this parallel,[15] a structural disruption of what de La Grange has described as follows:

«…that very idea which many listeners today consider one of the most audacious and brilliant ever conceived by Mahler –: the linking of two movements – one in quadruple, the other in triple time – with more or less the same thematic material»[11]

Moreover, de La Grange, referring to the 1919 Mengelberg telegram, has questioned the notion of Alma simply expressing a personal view of the movement order, and reiterates the historical fact of the original movement order:

«The fact that the initial order had the composer’s stamp of approval for two whole years prior to the premiere argues for further performances in that form…

«It is far more likely ten years after Mahler’s death and with a much clearer perspective on his life and career, Alma would have sought to be faithful to his artistic intentions. Thus, her telegram of 1919 still remains a strong argument today in favour of Mahler’s original order…it is stretching the bounds of both language and reason to describe [Andante-Scherzo] as the «only correct» one. Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, like many other compositions in the repertory, will always remain a «dual-version» work, but few of the others have attracted quite as much controversy.»[11]

De La Grange has noted the justification of having both options available for conductors to choose:

«…given that Mahler changed his mind so many times, it is understandable that a conductor might nowadays wish to stand by the order in the second version, if he is deeply convinced that he can serve the work better by doing this.»[12]

Mahler scholar Donald Mitchell echoed the dual-version scenario and the need for the availability of both options:

«I believe that all serious students of his music should make up their own minds about which order in their view represents Mahler’s genius. He was after all in two minds about it himself. We should let the music – how we hear it – decide! For me there is no right or wrong in this matter. We should continue to hear, quite legitimately, both versions of the symphony, according to the convictions of the interpreters involved. After all the first version has a fascinating history and legitimacy endowed by none other than the composer himself! Of course we must respect the fact of his final change of mind but to imagine that we should accept this without debate or comment beggars belief.»[11]

Matthews, Paul Banks and scholar Warren Darcy (the last an advocate for the Andante/Scherzo order) have independently proposed the idea of two separate editions of the symphony, one to accommodate each version of the order of the inner movements.[5][15] Music commentator David Hurwitz has likewise remarked:

«So as far as the facts go, then, we have on the one hand what Mahler actually did when he last performed the symphony, and on the other hand, what he originally composed and what his wife reported that he ultimately wanted. Any objective observer would be compelled to admit that this constitutes strong evidence for both perspectives. This being the case, the responsible thing to do in revisiting the need for a new Critical Edition would be to set out all of the arguments on each side, and then take no position. Let the performers decide, and admit frankly that if the criterion for making a decision regarding the correct order of the inner movements must be what Mahler himself ultimately wanted, then no final answer is possible.»[8]

An additional question is whether to restore the third hammer blow. Both the Ratz edition and the Kubik edition delete the third hammer blow. However, advocates on opposite sides of the inner movement debate, such as Del Mar and Matthews, have separately argued for restoration of the third hammer blow.[15]

Selected discography[edit]

This discography encompasses both audio and video recordings, and classifies them as to the order of the middle movements. Recordings with three hammer blows in the finale are noted with an asterisk (*).

Scherzo / Andante[edit]

- Erich Leinsdorf, Boston Symphony Orchestra, RCA Victor Red Seal LSC-7044

- Jascha Horenstein, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Unicorn UKCD 2024/5 (live recording from 1966)

- Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic,[16] Sony Classical SMK 60208 (*)

- Václav Neumann, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Berlin Classics 0090452BC

- George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra, Sony Classical SBK 47654

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Q-DISC 97014 (live performance from November 1968)

- Rafael Kubelík, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 478 7897-1

- Rafael Kubelík, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Audite 1475671 (live recording of 6 December 1968 performance)

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Philips 289 420 138-2

- Jascha Horenstein, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, BBC Legends BBCL4191-2

- Georg Solti, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Decca 414 674-2

- Hans Zender, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, CPO 999 477-2

- Maurice Abravanel, Utah Symphony, Vanguard Classics SRV 323/4 (LP)

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 415 099-2

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon DVD 440 073 409-05 (live film recording from October 1976) (*)

- James Levine, London Symphony Orchestra, RCA Red Seal RCD2-3213

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Saint Laurent Studio (live recording of 17 June 1977 performance)

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Fachmann FKM-CDR-193 (live recording of 27 August 1977 performance)

- Kirill Kondrashin, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Melodiya CD 10 00811

- Václav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic, Supraphon 11 1977-2

- Claudio Abbado, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 928-2

- Milan Horvat, Philharmonica Slavonica, Line 4593003

- Kirill Kondrashin, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classic 9842273 (live recording from January 1981)

- Lorin Maazel, Vienna Philharmonic, Sony Classical S14K 48198

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics CDC7 47050-8

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra. LPO-0038 (live recording from the 1983 Proms)

- Erich Leinsdorf, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orfeo C 554 011 B (live recording of 10 June 1983 performance)

- Gary Bertini, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics 94634 02382

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Philharmonia Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 082-2

- Eliahu Inbal, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, 1986, Denon Blu-spec cd (COCO-73280-1)

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 427 697-2 (*)

- Michiyoshi Inoue, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Pickwick/RPO CDRPO 9005

- Bernard Haitink, Berlin Philharmonic, Philips 289 426 257-2

- Riccardo Chailly, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Decca 444 871-2

- Hartmut Haenchen, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio 10 543

- Hiroshi Wakasugi, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 1989, Fontec FOCD9022/3

- Leif Segerstam, Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 8956/7

- Christoph von Dohnányi, Cleveland Orchestra, Decca 289 466 345-2

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics 7243 5 55294 28 (live recording from November 1991)

- Anton Nanut, Radio Symphony Orchestra Ljubljana, Zyx Classic CLS 4110

- Neeme Järvi, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 9207

- Antoni Wit, Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Naxos 8.550529

- Seiji Ozawa, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Philips 289 434 909-2

- Yevgeny Svetlanov, State Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation, Warner Classics 2564 68886-2 (box set)

- Emil Tabakov, Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio C49043

- Edo de Waart, Radio Filharmonisch Orkest, RCA 27607

- Pierre Boulez, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 445 835-2

- Zubin Mehta, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Warner Apex 9106459

- Thomas Sanderling, Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, RS Real Sound RS052-0186

- Yoel Levi, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Telarc CD 80444

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classics 93029

- Günther Herbig, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Classics 0094612BC

- Michiyoshi Inoue, New Japan Philharmonic, 2000, Exton OVCL-00121

- Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony, SFS Media 40382001 (recorded September 2001)

- Bernard Haitink, Orchestre National de France, Naïve V4937

- Christoph Eschenbach, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Ondine ODE1084-5B

- Mark Wigglesworth, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, MSO Live 391666

- Bernard Haitink, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, CSO Resound 210000045796

- Gabriel Feltz, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Dreyer Gaido 9595564

- Vladimir Fedoseyev, Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio, Relief 2735809

- Eiji Oue, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9253/4

- Takashi Asahina, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Green Door GDOP-2009

- Jonathan Nott, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Tudor 7191

- Esa-Pekka Salonen, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD275

- Hartmut Haenchen, Orchestre Symphonique du Théâtre de la Monnaie, ICA Classics DVD ICAD5018

- Antal Doráti, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Helicon 9699053 (live recording of 27 October 1963 performance)

- Lorin Maazel, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO 12101 DVD

- Paavo Järvi, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, C-Major DVD 729404

- Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Oslo Philharmonic, Simax PSC1316 (*)

- Pierre Boulez, Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra, Accentus Music ACC30230

- Antonio Pappano, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, EMI Classics (Warner Classics 5099908441324)

- Lorin Maazel, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD361

- Jaap van Zweden, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, DSO Live

- Libor Pešek, Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Out of the Frame OUT 068

- Václav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00259

- Zdeněk Mácal, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00245

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00051

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2007, Fontec SACD (FOCD9369)

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2013, Exton SACD (OVCL-00516 & OVXL-00090 «one point recording version»)

- Gary Bertini, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9182

- Georges Prêtre, Wiener Symphoniker, Weitblick SSS0079-2

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0108-2

- Rudolf Barshai, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, Tobu YNSO Archive Series YASCD1009-2

- Martin Sieghart, Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton HGO 0403

- Heinz Bongartz, Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0053-2

- Teodor Currentzis, MusicAeterna, Sony Classical 19075822952

- Paavo Järvi, NHK Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo, RCA Victor Red Seal SICC 19040

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, SWR Classic SWR19080CD (live concert performance from 1971)

- Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony, SFS Media (digital release, UPC 821936007723, live recording of September 2019)

- Tomáš Netopil, Essen Philharmonic, Oehms Classics OC 1716

- Jahja Ling, San Diego Symphony, San Diego Symphony proprietary label, Jacobs Masterworks (recorded 2008)

Andante / Scherzo[edit]

- Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Spa Records SPA 59/60

- Eduard Flipse, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Philips ABL 3103-4 (LP), Naxos Classical Archives 9.80846-48 (CD)

- Dimitri Mitropoulos, New York Philharmonic,[16] NYP Editions (live recording from 10 April 1955)

- Eduard van Beinum, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Tahra 614/5 (live recording from 7 December 1955)

- Sir John Barbirolli, Berlin Philharmonic, Testament SBT1342 (live recording of 13 January 1966 performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli. New Philharmonia Orchestra, Testament SBT1451 (live recording of 16 August 1967 Proms performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli, New Philharmonia Orchestra, EMI 7 67816 2 (studio recording, 17–19 August 1967)

- Harold Farberman, London Symphony Orchestra, Vox 7212 (CD)

- Heinz Rögner, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Eterna 8-27 612-613

- Simon Rattle, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics CDS5 56925-2

- Glen Cortese, Manhattan School of Music Symphony Orchestra, Titanic 257

- Andrew Litton, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Delos (live recording, limited commemorative edition)

- Sir Charles Mackerras, BBC Philharmonic, BBC Music Magazine MM251 (Vol 13, No 7) (*)

- Mariss Jansons, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0038

- Claudio Abbado, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 557-39

- Iván Fischer, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Channel Classics 22905

- Mariss Jansons, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO06001

- Claudio Abbado, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Euroarts DVD 2055648

- Simone Young, Hamburg Philharmonic, Oehms Classics OC413

- David Zinman, Tonhalle Orchester Zürich, RCA Red Seal 88697 45165 2

- Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0661

- Jonathan Darlington, Duisburg Philharmonic, Acousence 7944879

- Petr Vronsky, Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra, ArcoDiva UP0122-2

- Fabio Luisi, Vienna Symphony, Live WS003

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, SSO Live

- Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Accentus Music DVD ACC-2068

- Markus Stenz, Gürzenich Orchestra Köln, Oehms Classics OC651

- Daniel Harding, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BR-Klassik 900132

- Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, BPH 7558515 (live recording from 1987)

- James Levine, Boston Symphony Orchestra, BSO Classics 0902-D

- Osmo Vänskä, Minnesota Orchestra, BIS 2266

- Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (live recordings from 1987 and 2018, with DVD of 2018 performance)

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, SWR Classic SWR19080CD (live concert performance from 2013)

- Hans Rosbaud, Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra, SWR 19099 (live recording)

- Ádám Fischer, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker, CAvi-music AVI 8553490 (*)

Premieres[edit]

- World premiere: 27 May 1906, Saalbau Essen, conducted by the composer

- Dutch première: 16 September 1916, Amsterdam, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Willem Mengelberg

- American premiere: 11 December 1947, New York City, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos

- Recording premiere: F. Charles Adler conducting the Vienna Symphony, 1952

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rabinowitz, Peter J. (September 1981). «Pleasure in Conflict: Mahler’s Sixth, Tragedy, and Musical Form». Comparative Literature Studies. 18 (3): 306–313. JSTOR 40246269.

- ^ Sybill Mahlke (29 June 2008). «Wo der Hammer hängt Komische Oper». Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Es gibt doch nur eine VI. trotz der Pastorale.» (There is only one Sixth, notwithstanding the Pastoral)

- ^ «Mahler 6: Hammer!». Südwestrundfunk (in German). Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e Kubik, Reinhold (2004). «Analysis versus history: Erwin Ratz and the Sixth Symphony» (PDF). In Gilbert Kaplan (ed.). The Correct Movement Order in Mahler’s Sixth Symphony. New York, New York: The Kaplan Foundation. ISBN 0-9749613-0-2.

- ^ a b c Darcy, Warren (Summer 2001). «Rotational Form, Teleological Genesis, and Fantasy-Projection in the Slow Movement of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony». 19th-Century Music. XXV (1): 49–74. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49.

- ^ Dika Newlin, Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, New York, 1947, pp. 184–5.

- ^ Monahan, Seth (Spring 2011). ««I have tried to capture you …»: Rethinking the «Alma» Theme from Mahler’s Sixth Symphony». Journal of the American Musicological Society. 64 (1): 119–178. doi:10.1525/jams.2011.64.1.119.

- ^ a b c d e f David Hurwitz (May 2020). «Mahler: Symphony No. 6 (study score). Neue Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Reinhold Kubik, ed. C.F. Peters and Kaplan Foundation. EP 11210» (PDF). Classics Today. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Tony Duggan (May 2007). «The Mahler Symphonies – A synoptic survey by Tony Duggan: Symphony No. 6». MusicWeb International. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Robert Beale (2015-10-02). «Interview with Sir Mark Elder as he prepares to conduct the Halle in a Mahler marathon». Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k de La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler, Volume 4: A New Life Cut Short, Oxford University Press (2008), pp. 1578-1587. ISBN 9780198163879.

- ^ a b c d e f de La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler: Volume 3. Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion, Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), pp. 808–841 (ISBN 0-19-315160-X).

- ^ Del Mar, Norman, Mahler’s Sixth Symphony – A Study. Eulenberg Books (London), ISBN 9780903873291, pp. 34–64 (1980).

- ^ Füssl, Karl Heinz, «Zur Stellung des Mittelsätze in Mahlers Sechste Symphonie». Nachricthen zur Mahler Forschung, 27, International Gustav Mahler Society (Vienna), March 1992.

- ^ a b c d Matthews, David, ‘The Sixth Symphony’, in The Mahler Companion (eds Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson). Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), ISBN 0-19-816376-2, pp. 366–375 (1999).

- ^ a b Mahler Symphony No. 6 at the New York Philharmonic, graphic showing movement order and number of hammer blows, 11 February 2016

External links[edit]

- Symphony No. 6: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- MahlerFest XVI, 2003 programme book

- David Matthews, ‘The order of the middle movements in Mahler’s Sixth Symphony’ (website blog entry), January 2016

| Symphony No. 6 | |

|---|---|

| by Gustav Mahler | |

| Gustav Mahler in 1907 | |

| Key | A minor |

| Composed | 1903–1904: Maiernigg |

| Published |

|

| Recorded | F. Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony, 1952 |

| Duration | 77–85 minutes |

| Movements | 4 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 27 May 1906 |

| Location | Saalbau Essen |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

The Symphony No. 6 in A minor by Gustav Mahler is a symphony in four movements, composed in 1903 and 1904, with revisions from 1906. It is sometimes nicknamed the Tragic («Tragische»), though the origin of the name is unclear.[1]

Introduction[edit]

Mahler conducted the work’s first performance at the Saalbau concert hall in Essen on 27 May 1906. Mahler composed the symphony at an exceptionally happy time in his life, as he had married Alma Schindler in 1902, and during the course of the work’s composition his second daughter was born. This contrasts with the tragic, even nihilistic, ending of No. 6. Both Alban Berg and Anton Webern praised the work when they first heard it. In a 1908 letter to Webern, Berg said in his opinion there was just one «sixth symphony», despite that of Beethoven.[2]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for large orchestra, consisting of the following:

Contemporary caricature about the unorthodox usage of a hammer: «My god, I forgot the car horn! Now I can write another symphony.» (Die Muskete [de], 19 January 1907)

In addition to very large woodwind and brass sections, Mahler augmented the percussion section with several unusual instruments, including the famous «Mahler hammer». The sound of the hammer, which features in the last movement, was stipulated by Mahler to be «brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe).» The sound achieved in the premiere did not quite carry far enough from the stage, and indeed the problem of achieving the proper volume while still remaining dull in resonance remains a challenge to the modern orchestra. Various methods of producing the sound have involved a wooden mallet striking a wooden surface, a sledgehammer striking a wooden box, or a particularly large bass drum, or sometimes simultaneous use of more than one of these methods. Contemporaries mocked the use of the hammer, as shown by a caricature from the satirical magazine Die Muskete [de].[3]

Nickname of Tragische[edit]

The status of the symphony’s nickname is problematic.[1] Mahler did not title the symphony when he composed it, or at its first performance or first publication. When he allowed Richard Specht to analyse the work and Alexander von Zemlinsky to arrange the symphony, he did not authorize any sort of nickname for the symphony. He had, as well, decisively rejected and disavowed the titles (and programmes) of his earlier symphonies by 1900. Only the words «Sechste Sinfonie» appeared on the programme for the performance in Munich on November 8, 1906.[4]: 59 Nor does the word Tragische appear on any of the scores that C. F. Kahnt published (first edition, 1906; revised edition, 1906), in Specht’s officially approved Thematische Führer (‘thematic guide’)[4]: 50 or on Zemlinsky’s piano duet transcription (1906).[4]: 57 By contrast, in his Gustav Mahler memoir, Bruno Walter claimed that «Mahler called [the work] his Tragic Symphony«. Additionally, the programme for the first Vienna performance (January 4, 1907) refers to the work as «Sechste Sinfonie (Tragische)«.

Structure[edit]

The work is in four movements and has a duration of around 80 minutes. The order of the inner movements has been a matter of controversy. The first published edition of the score (C. F. Kahnt, 1906) featured the movements in the following order:[5]

- Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.

- Scherzo: Wuchtig

- Andante moderato

- Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico

Mahler later placed the Andante as the second movement, and this new order of the inner movements was reflected in the second and third published editions of the score, as well as the Essen premiere.

- Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.

- Andante moderato

- Scherzo: Wuchtig

- Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico

The first three movements are relatively traditional in structure and character, with a standard sonata form first movement (even including an exact repeat of the exposition, unusual in Mahler) leading to the middle movements – one a scherzo-with-trios, the other slow. However, attempts to analyze the vast finale in terms of the sonata archetype have encountered serious difficulties. As Dika Newlin has pointed out:

it has elements of what is conventionally known as ‘sonata form’, but the music does not follow a set pattern … Thus, ‘expositional’ treatment merges directly into the type of contrapuntal and modulatory writing appropriate to ‘elaboration’ sections …; the beginning of the principal theme-group is recapitulated in C minor rather than in A minor, and the C minor chorale theme … of the exposition is never recapitulated at all.[6]

I. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig.[edit]

The first movement, which for the most part has the character of a march, features a motif consisting of an A major triad turning to A minor over a distinctive timpani rhythm. The chords are played by trumpets and oboes when first heard, with the trumpets sounding the loudest in the first chord and the oboes in the second.

This motif reappears in subsequent movements. The first movement also features a soaring melody which the composer’s wife, Alma Mahler, claimed represented her. This melody is often called the «Alma theme».[7] A restatement of that theme at the movement’s end marks the happiest point of the symphony.

II. Scherzo: Wuchtig[edit]

The scherzo marks a return to the unrelenting march rhythms of the first movement, though in a ‘triple-time’ metrical context.

Its trio (the middle section), marked Altväterisch (‘old-fashioned’), is rhythmically irregular (4

8 switching to 3

8 and 3

4) and of a somewhat gentler character.

According to Alma Mahler, in this movement Mahler «represented the arrhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zigzags over the sand». The chronology of its composition suggests otherwise. The movement was composed in the summer of 1903, when Maria Anna (born November 1902) was less than a year old. Anna Justine was born a year later in July 1904.[citation needed]

III. Andante moderato[edit]

Performed by the Virtual Philharmonic Orchestra (Reinhold Behringer) with digital samples

The andante provides a respite from the intensity of the rest of the work. Its main theme is an introspective ten-bar phrase in E♭ major, though it frequently touches on the minor mode as well. The orchestration is more delicate and reserved in this movement, making it all the more poignant when compared to the other three.

IV. Finale: Sostenuto – Allegro moderato – Allegro energico[edit]

The last movement is an extended sonata form, characterized by drastic changes in mood and tempo, the sudden change of glorious soaring melody to deep agony.

The movement is punctuated by two hammer blows. The original score had five hammer blows, which Mahler subsequently reduced to three, and eventually to two.[8][9]

Alma quoted her husband as saying that these were three mighty blows of fate befallen by the hero, «the third of which fells him like a tree». She identified these blows with three later events in Gustav Mahler’s own life: the death of his eldest daughter Maria Anna Mahler, the diagnosis of an eventually fatal heart condition, and his forced resignation from the Vienna Opera and departure from Vienna. When he revised the work, Mahler removed the last of these three hammer strokes so that the music built to a sudden moment of stillness in place of the third blow. Some recordings and performances, notably those of Leonard Bernstein, have restored the third hammer blow.[10] The piece ends with the same rhythmic motif that appeared in the first movement, but the chord above it is a simple A minor triad, rather than A major turning into A minor. After the third ‘hammer-blow’ passage, the music gropes in darkness and then the trombones and horns begin to offer consolation. However, after they turn briefly to major they fade away and the final bars erupt fff in the minor.

Order of the inner movements and performance history issue[edit]

Controversy exists over the order of the two middle movements. Mahler conceived the work as having the scherzo second and the slow movement third, a somewhat unclassical arrangement adumbrated in such earlier large-scale symphonies as Beethoven’s No. 9, Bruckner’s No. 8 and (unfinished) No. 9, and Mahler’s own four-movement No. 1 and No. 4. It was in this arrangement that the symphony was completed (in 1904) and published (in March 1906); and it was with a conducting score in which the scherzo preceded the slow movement that Mahler began rehearsals for the work’s first performance, as noted by Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange:

«Scherzo 2» was undeniably the original order, the one in which Mahler first conceived, composed, and published the Sixth Symphony, and also the one in which he rehearsed the work with two different orchestras before changing his mind at the last minute before the premiere.[11]

Alfred Roller, a close collaborator and colleague of Mahler’s in Vienna, communicated in a 2 May 1906 letter to his fiancée Mileva Stojsavljevic, on the Mahlers’ reaction to the 1 May 1906 orchestral rehearsal of the work in Vienna, in its original movement order:

Today I was there at noon, but I could not talk much with Alma, since M[ahler] was almost always there, I saw only that the two of them were very happy and satisfied…[11]

During those later May 1906 rehearsals in Essen, however, Mahler decided that the slow movement should precede the scherzo. Klaus Pringsheim, another colleague of Mahler’s at the Hofoper, reminisced in a 1920 article on the situation at the Essen rehearsals, on Mahler’s state of mind at the time:

Those close to him were well aware of Mahler’s «insecurity». Even after the final rehearsal he was still not sure whether or not he had found the right tempo for the Scherzo, and had wondered whether he should invert the order of the second and third movements (which he subsequently did).[11]

Mahler instructed his publishers Christian Friedrich Kahnt [de] to prepare a «second edition» of the work with the movements in that order, and meanwhile to insert errata slips indicating the change of order into all unsold copies of the existing edition. Mahler conducted the 27 May 1906 public premiere, and his other two subsequent performances of the Sixth Symphony, in November 1906 (Munich) and 4 January 1907 (Vienna) with his revised order of the inner movements. In the period immediately after Mahler’s death, scholars such as Paul Bekker, Ernst Decsey, Richard Specht, and Paul Stefan published studies with reference to the Sixth Symphony in Mahler’s second edition with the Andante/Scherzo order.[12]

One of the first occasions after Mahler’s death where the conductor reverted to the original movement order is in 1919/1920, after an inquiry in the autumn of 1919 from Willem Mengelberg to Alma Mahler in preparation for the May 1920 Mahler Festival in Amsterdam of the complete symphonies, regarding the order of the inner movements of the Sixth Symphony. In a telegram dated 1 October 1919, Alma responded to Mengelberg:[12]

Erst Scherzo dann Andante herzlichst Alma («First Scherzo then Andante affectionately Alma»)[12]

Mengelberg, who had been in close touch with Mahler until the latter’s death, and had conducted the symphony in the «Andante/Scherzo» arrangement up to 1916, then switched to the «Scherzo/Andante» order. In his own copy of the score, he wrote on the first page:[12]

Nach Mahlers Angabe II erst Scherzo dann III Andante («According to Mahler’s indications, first II Scherzo, then III Andante»)[11]

Other conductors, such as Oskar Fried, continued to perform (and eventually record) the work as ‘Andante/Scherzo’, per the second edition, right up to the early 1960s. Exceptions included two performances in Vienna on 14 December 1930 and 23 May 1933, conducted by Anton Webern, who utilised the Scherzo/Andante order of the inner movements. Anna Mahler, Mahler’s daughter, attended both of these performances.[11] De La Grange commented on Webern’s choice of the Scherzo/Andante order:

Anton Webern had favoured the original order of movements in the two performances he conducted in Vienna on 14 December 1930 and 23 May 1933. Webern was not only a great composer, but also one of Mahler’s earliest and most passionate devotees and a much admired conductor of Mahler’s music…it is inconceivable that he could have performed a version that would have shocked and displeased his beloved master and mentor.»[11]

In 1963, a new critical edition of the Sixth Symphony appeared, under the auspices of the Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft (IGMG) and its president, Erwin Ratz, a pupil of Webern,[11] an edition which restored Mahler’s original order of the inner movements. Ratz, however, did not offer documented support, such as Alma Mahler’s 1919 telegram, for his assertion that Mahler «changed his mind a second time» at some point before his death. In his analysis of the Sixth Symphony, Norman Del Mar argued for the Andante/Scherzo order of the inner movements,[4]: 43 [13] and criticised the Ratz edition for its lack of documentary evidence to justify the Scherzo/Andante order. In contrast, scholars such as Theodor W. Adorno, Henry-Louis de La Grange, Hans-Peter Jülg and Karl Heinz Füssl have argued for the original order as more appropriate, expostulating on the overall tonal scheme and the various relationships between the keys in the final three movements. Füssl, in particular, noted that Ratz made his decision under historical circumstances where the history of the different autographs and versions was not completely known at the time.[12] Füssl has also noted the following features of the Scherzo/Andante order:[14]

- The Scherzo is an example of ‘developing variation’ in its treatment of material from the first movement, where separation of the Scherzo from the first movement by the Andante disrupts that linkage.

- The Scherzo and the first movement use identical keys, A minor at the beginning and F major in the trio.

- The Andante’s key, E♭ major, is farthest removed from the key at the close of the first movement (A major), whilst the C minor key at the beginning of the finale acts as transition from E♭ major to A minor, the principal key of the finale.

The 1968 Eulenberg Edition of the Sixth Symphony, edited by Hans Redlich, restores most of Mahler’s original orchestration and utilises the original order of Scherzo/Andante for the order of the middle movements.[8] The most recent IGMG critical edition of the Sixth Symphony was published in 2010, under the general editorship of Reinhold Kubik, and uses the Andante/Scherzo order for the middle movements.[8] Kubik had previously declared in 2004:

- «As the current Chief Editor of the Complete Critical Edition, I declare the official position of the institution I represent is that the correct order of the middle movements of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony is Andante-Scherzo.»[4]

This statement has been criticised, in the manner of earlier criticism of Ratz, on several levels:

- for itself lacking documentary support and for expressing a personal preference based on subjective animus related to the Alma Problem, rather than any actual documentary evidence[8]

- for its blanket dismissal of the evidence of the original score with the Scherzo/Andante order[11]

- for imposing an advance bias rather than allowing musicians to arrive at their own choice independently.[8]

British composer David Matthews was a former adherent of the Andante/Scherzo order,[5] but has since changed his mind and now argues for Scherzo/Andante as the preferred order, again citing the overall tonal scheme of the symphony.[15] In keeping with Mahler’s original order, British conductor John Carewe has noted parallels between the tonal plan of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 and Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, with the Scherzo/Andante order of movements in the latter. David Matthews has noted the interconnectivity of the first movement with the Scherzo as similar to Mahler’s interconnectivity of the first two movements of the Fifth Symphony, and that performing the Mahler with the Andante/Scherzo order would damage the structure of the tonal key relationships and remove this parallel,[15] a structural disruption of what de La Grange has described as follows:

«…that very idea which many listeners today consider one of the most audacious and brilliant ever conceived by Mahler –: the linking of two movements – one in quadruple, the other in triple time – with more or less the same thematic material»[11]

Moreover, de La Grange, referring to the 1919 Mengelberg telegram, has questioned the notion of Alma simply expressing a personal view of the movement order, and reiterates the historical fact of the original movement order:

«The fact that the initial order had the composer’s stamp of approval for two whole years prior to the premiere argues for further performances in that form…

«It is far more likely ten years after Mahler’s death and with a much clearer perspective on his life and career, Alma would have sought to be faithful to his artistic intentions. Thus, her telegram of 1919 still remains a strong argument today in favour of Mahler’s original order…it is stretching the bounds of both language and reason to describe [Andante-Scherzo] as the «only correct» one. Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, like many other compositions in the repertory, will always remain a «dual-version» work, but few of the others have attracted quite as much controversy.»[11]

De La Grange has noted the justification of having both options available for conductors to choose:

«…given that Mahler changed his mind so many times, it is understandable that a conductor might nowadays wish to stand by the order in the second version, if he is deeply convinced that he can serve the work better by doing this.»[12]

Mahler scholar Donald Mitchell echoed the dual-version scenario and the need for the availability of both options:

«I believe that all serious students of his music should make up their own minds about which order in their view represents Mahler’s genius. He was after all in two minds about it himself. We should let the music – how we hear it – decide! For me there is no right or wrong in this matter. We should continue to hear, quite legitimately, both versions of the symphony, according to the convictions of the interpreters involved. After all the first version has a fascinating history and legitimacy endowed by none other than the composer himself! Of course we must respect the fact of his final change of mind but to imagine that we should accept this without debate or comment beggars belief.»[11]

Matthews, Paul Banks and scholar Warren Darcy (the last an advocate for the Andante/Scherzo order) have independently proposed the idea of two separate editions of the symphony, one to accommodate each version of the order of the inner movements.[5][15] Music commentator David Hurwitz has likewise remarked:

«So as far as the facts go, then, we have on the one hand what Mahler actually did when he last performed the symphony, and on the other hand, what he originally composed and what his wife reported that he ultimately wanted. Any objective observer would be compelled to admit that this constitutes strong evidence for both perspectives. This being the case, the responsible thing to do in revisiting the need for a new Critical Edition would be to set out all of the arguments on each side, and then take no position. Let the performers decide, and admit frankly that if the criterion for making a decision regarding the correct order of the inner movements must be what Mahler himself ultimately wanted, then no final answer is possible.»[8]

An additional question is whether to restore the third hammer blow. Both the Ratz edition and the Kubik edition delete the third hammer blow. However, advocates on opposite sides of the inner movement debate, such as Del Mar and Matthews, have separately argued for restoration of the third hammer blow.[15]

Selected discography[edit]

This discography encompasses both audio and video recordings, and classifies them as to the order of the middle movements. Recordings with three hammer blows in the finale are noted with an asterisk (*).

Scherzo / Andante[edit]

- Erich Leinsdorf, Boston Symphony Orchestra, RCA Victor Red Seal LSC-7044

- Jascha Horenstein, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Unicorn UKCD 2024/5 (live recording from 1966)

- Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic,[16] Sony Classical SMK 60208 (*)

- Václav Neumann, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Berlin Classics 0090452BC

- George Szell, Cleveland Orchestra, Sony Classical SBK 47654

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Q-DISC 97014 (live performance from November 1968)

- Rafael Kubelík, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 478 7897-1

- Rafael Kubelík, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Audite 1475671 (live recording of 6 December 1968 performance)

- Bernard Haitink, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Philips 289 420 138-2

- Jascha Horenstein, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, BBC Legends BBCL4191-2

- Georg Solti, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Decca 414 674-2

- Hans Zender, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, CPO 999 477-2

- Maurice Abravanel, Utah Symphony, Vanguard Classics SRV 323/4 (LP)

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 415 099-2

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon DVD 440 073 409-05 (live film recording from October 1976) (*)

- James Levine, London Symphony Orchestra, RCA Red Seal RCD2-3213

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Saint Laurent Studio (live recording of 17 June 1977 performance)

- Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic, Fachmann FKM-CDR-193 (live recording of 27 August 1977 performance)

- Kirill Kondrashin, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Melodiya CD 10 00811

- Václav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic, Supraphon 11 1977-2

- Claudio Abbado, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 928-2

- Milan Horvat, Philharmonica Slavonica, Line 4593003

- Kirill Kondrashin, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classic 9842273 (live recording from January 1981)

- Lorin Maazel, Vienna Philharmonic, Sony Classical S14K 48198

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics CDC7 47050-8

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra. LPO-0038 (live recording from the 1983 Proms)

- Erich Leinsdorf, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orfeo C 554 011 B (live recording of 10 June 1983 performance)

- Gary Bertini, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics 94634 02382

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Philharmonia Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 289 423 082-2

- Eliahu Inbal, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, 1986, Denon Blu-spec cd (COCO-73280-1)

- Leonard Bernstein, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 427 697-2 (*)

- Michiyoshi Inoue, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Pickwick/RPO CDRPO 9005

- Bernard Haitink, Berlin Philharmonic, Philips 289 426 257-2

- Riccardo Chailly, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Decca 444 871-2

- Hartmut Haenchen, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio 10 543

- Hiroshi Wakasugi, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 1989, Fontec FOCD9022/3

- Leif Segerstam, Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 8956/7

- Christoph von Dohnányi, Cleveland Orchestra, Decca 289 466 345-2

- Klaus Tennstedt, London Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI Classics 7243 5 55294 28 (live recording from November 1991)

- Anton Nanut, Radio Symphony Orchestra Ljubljana, Zyx Classic CLS 4110

- Neeme Järvi, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Chandos CHAN 9207

- Antoni Wit, Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Naxos 8.550529

- Seiji Ozawa, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Philips 289 434 909-2

- Yevgeny Svetlanov, State Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation, Warner Classics 2564 68886-2 (box set)

- Emil Tabakov, Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra, Capriccio C49043

- Edo de Waart, Radio Filharmonisch Orkest, RCA 27607

- Pierre Boulez, Vienna Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 445 835-2

- Zubin Mehta, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Warner Apex 9106459

- Thomas Sanderling, Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, RS Real Sound RS052-0186

- Yoel Levi, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Telarc CD 80444

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Hänssler Classics 93029

- Günther Herbig, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Classics 0094612BC

- Michiyoshi Inoue, New Japan Philharmonic, 2000, Exton OVCL-00121

- Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony, SFS Media 40382001 (recorded September 2001)

- Bernard Haitink, Orchestre National de France, Naïve V4937

- Christoph Eschenbach, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Ondine ODE1084-5B

- Mark Wigglesworth, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, MSO Live 391666

- Bernard Haitink, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, CSO Resound 210000045796

- Gabriel Feltz, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Dreyer Gaido 9595564

- Vladimir Fedoseyev, Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio, Relief 2735809

- Eiji Oue, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9253/4

- Takashi Asahina, Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra, Green Door GDOP-2009

- Jonathan Nott, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Tudor 7191

- Esa-Pekka Salonen, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD275

- Hartmut Haenchen, Orchestre Symphonique du Théâtre de la Monnaie, ICA Classics DVD ICAD5018

- Antal Doráti, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Helicon 9699053 (live recording of 27 October 1963 performance)

- Lorin Maazel, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO 12101 DVD

- Paavo Järvi, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, C-Major DVD 729404

- Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Oslo Philharmonic, Simax PSC1316 (*)

- Pierre Boulez, Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra, Accentus Music ACC30230

- Antonio Pappano, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, EMI Classics (Warner Classics 5099908441324)

- Lorin Maazel, Philharmonia Orchestra, Signum SIGCD361

- Jaap van Zweden, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, DSO Live

- Libor Pešek, Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Out of the Frame OUT 068

- Václav Neumann, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00259

- Zdeněk Mácal, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00245

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Czech Philharmonic, Exton OVCL-00051

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2007, Fontec SACD (FOCD9369)

- Eliahu Inbal, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, 2013, Exton SACD (OVCL-00516 & OVXL-00090 «one point recording version»)

- Gary Bertini, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Fontec FOCD9182

- Georges Prêtre, Wiener Symphoniker, Weitblick SSS0079-2

- Giuseppe Sinopoli, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0108-2

- Rudolf Barshai, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, Tobu YNSO Archive Series YASCD1009-2

- Martin Sieghart, Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra, Exton HGO 0403

- Heinz Bongartz, Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Weitblick SSS0053-2

- Teodor Currentzis, MusicAeterna, Sony Classical 19075822952

- Paavo Järvi, NHK Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo, RCA Victor Red Seal SICC 19040

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, SWR Classic SWR19080CD (live concert performance from 1971)

- Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony, SFS Media (digital release, UPC 821936007723, live recording of September 2019)

- Tomáš Netopil, Essen Philharmonic, Oehms Classics OC 1716

- Jahja Ling, San Diego Symphony, San Diego Symphony proprietary label, Jacobs Masterworks (recorded 2008)

Andante / Scherzo[edit]

- Charles Adler, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Spa Records SPA 59/60

- Eduard Flipse, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Philips ABL 3103-4 (LP), Naxos Classical Archives 9.80846-48 (CD)

- Dimitri Mitropoulos, New York Philharmonic,[16] NYP Editions (live recording from 10 April 1955)

- Eduard van Beinum, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam, Tahra 614/5 (live recording from 7 December 1955)

- Sir John Barbirolli, Berlin Philharmonic, Testament SBT1342 (live recording of 13 January 1966 performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli. New Philharmonia Orchestra, Testament SBT1451 (live recording of 16 August 1967 Proms performance)

- Sir John Barbirolli, New Philharmonia Orchestra, EMI 7 67816 2 (studio recording, 17–19 August 1967)

- Harold Farberman, London Symphony Orchestra, Vox 7212 (CD)

- Heinz Rögner, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Eterna 8-27 612-613

- Simon Rattle, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, EMI Classics CDS5 56925-2

- Glen Cortese, Manhattan School of Music Symphony Orchestra, Titanic 257

- Andrew Litton, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Delos (live recording, limited commemorative edition)

- Sir Charles Mackerras, BBC Philharmonic, BBC Music Magazine MM251 (Vol 13, No 7) (*)

- Mariss Jansons, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0038

- Claudio Abbado, Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 557-39

- Iván Fischer, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Channel Classics 22905

- Mariss Jansons, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, RCO Live RCO06001

- Claudio Abbado, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Euroarts DVD 2055648

- Simone Young, Hamburg Philharmonic, Oehms Classics OC413

- David Zinman, Tonhalle Orchester Zürich, RCA Red Seal 88697 45165 2

- Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live LSO0661

- Jonathan Darlington, Duisburg Philharmonic, Acousence 7944879

- Petr Vronsky, Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra, ArcoDiva UP0122-2

- Fabio Luisi, Vienna Symphony, Live WS003

- Vladimir Ashkenazy, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, SSO Live

- Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Accentus Music DVD ACC-2068

- Markus Stenz, Gürzenich Orchestra Köln, Oehms Classics OC651

- Daniel Harding, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BR-Klassik 900132

- Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, BPH 7558515 (live recording from 1987)

- James Levine, Boston Symphony Orchestra, BSO Classics 0902-D

- Osmo Vänskä, Minnesota Orchestra, BIS 2266

- Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (live recordings from 1987 and 2018, with DVD of 2018 performance)

- Michael Gielen, SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, SWR Classic SWR19080CD (live concert performance from 2013)

- Hans Rosbaud, Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra, SWR 19099 (live recording)

- Ádám Fischer, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker, CAvi-music AVI 8553490 (*)

Premieres[edit]

- World premiere: 27 May 1906, Saalbau Essen, conducted by the composer

- Dutch première: 16 September 1916, Amsterdam, with the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Willem Mengelberg

- American premiere: 11 December 1947, New York City, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos

- Recording premiere: F. Charles Adler conducting the Vienna Symphony, 1952

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rabinowitz, Peter J. (September 1981). «Pleasure in Conflict: Mahler’s Sixth, Tragedy, and Musical Form». Comparative Literature Studies. 18 (3): 306–313. JSTOR 40246269.

- ^ Sybill Mahlke (29 June 2008). «Wo der Hammer hängt Komische Oper». Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Es gibt doch nur eine VI. trotz der Pastorale.» (There is only one Sixth, notwithstanding the Pastoral)

- ^ «Mahler 6: Hammer!». Südwestrundfunk (in German). Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e Kubik, Reinhold (2004). «Analysis versus history: Erwin Ratz and the Sixth Symphony» (PDF). In Gilbert Kaplan (ed.). The Correct Movement Order in Mahler’s Sixth Symphony. New York, New York: The Kaplan Foundation. ISBN 0-9749613-0-2.

- ^ a b c Darcy, Warren (Summer 2001). «Rotational Form, Teleological Genesis, and Fantasy-Projection in the Slow Movement of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony». 19th-Century Music. XXV (1): 49–74. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49.

- ^ Dika Newlin, Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, New York, 1947, pp. 184–5.

- ^ Monahan, Seth (Spring 2011). ««I have tried to capture you …»: Rethinking the «Alma» Theme from Mahler’s Sixth Symphony». Journal of the American Musicological Society. 64 (1): 119–178. doi:10.1525/jams.2011.64.1.119.

- ^ a b c d e f David Hurwitz (May 2020). «Mahler: Symphony No. 6 (study score). Neue Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Reinhold Kubik, ed. C.F. Peters and Kaplan Foundation. EP 11210» (PDF). Classics Today. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Tony Duggan (May 2007). «The Mahler Symphonies – A synoptic survey by Tony Duggan: Symphony No. 6». MusicWeb International. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ^ Robert Beale (2015-10-02). «Interview with Sir Mark Elder as he prepares to conduct the Halle in a Mahler marathon». Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k de La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler, Volume 4: A New Life Cut Short, Oxford University Press (2008), pp. 1578-1587. ISBN 9780198163879.

- ^ a b c d e f de La Grange, Henry-Louis, Gustav Mahler: Volume 3. Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion, Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), pp. 808–841 (ISBN 0-19-315160-X).

- ^ Del Mar, Norman, Mahler’s Sixth Symphony – A Study. Eulenberg Books (London), ISBN 9780903873291, pp. 34–64 (1980).

- ^ Füssl, Karl Heinz, «Zur Stellung des Mittelsätze in Mahlers Sechste Symphonie». Nachricthen zur Mahler Forschung, 27, International Gustav Mahler Society (Vienna), March 1992.

- ^ a b c d Matthews, David, ‘The Sixth Symphony’, in The Mahler Companion (eds Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson). Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK), ISBN 0-19-816376-2, pp. 366–375 (1999).

- ^ a b Mahler Symphony No. 6 at the New York Philharmonic, graphic showing movement order and number of hammer blows, 11 February 2016

External links[edit]

- Symphony No. 6: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- MahlerFest XVI, 2003 programme book

- David Matthews, ‘The order of the middle movements in Mahler’s Sixth Symphony’ (website blog entry), January 2016

Symphony No. 6 (a-moll), «Tragische»

Композитор

Год создания

1904

Дата премьеры

27.05.1906

Жанр

Страна

Австрия

Состав оркестра: 4 флейты, флейта-пикколо, 4 гобоя, английский рожок, 3 кларнета, кларнет-пикколо, бас-кларнет, 3 фагота, контрафагот, 8 валторн, 6 труб, 4 тромбона, туба, 2 литавры, колокольчики, ксилофон, челеста, пастушьи колокольца, низкие колокола, большой барабан, малый барабан, треугольник, 2 пары тарелок, прутья, тамтам, молот, 2 арфы, усиленная струнная группа.

История создания

Шестая симфония создавалась на протяжении двух летних каникул — 1903 и 1904 годов. В это время Малер — директор Королевской оперы Вены, счастливый муж первой венской красавицы и отец крошечной дочери (в 1904-м — уже двух дочерей). Его музыка по-прежнему находит признание только у немногих знатоков, друзей-музыкантов. Но он верит, что его время придет и продолжает писать, как только находит для этого время.

В первые годы XX века им создаются песни на стихи поэта Ф. Рюккерта — единственного, кто близок ему духовно, кто вдохновляет его на творчество. Это цикл «Песни об умерших детях» — пять песен на стихи, созданные поэтом после смерти его детей, и еще пять песен на стихи того же поэта, которые вместе с двумя, написанными на тексты сборника Арнима и Брентано «Чудесный рог мальчика» составили «Семь песен последних лет».

- Малер — лучшее в интернет-магазине OZON.ru

Вокальные миниатюры можно было писать «между прочим», но симфония требовала сосредоточенности. А это было возможно только во время летнего отдыха, когда композитор уединялся где-нибудь в глуши, далеко от забот театра и большого города. Последние годы это был Майерниг. Летом 1904 года он пишет оттуда своему младшему коллеге, будущему великому дирижеру и страстному пропагандисту его произведений Бруно Вальтеру в ответ на его письмо, в котором тот высказывается против программной музыки: «Моя Шестая готова. Думаю, что я смог ! Тысячу раз баста!» Итак, новая симфония снова программна. По своей структуре она традиционна — классический четырехчастный цикл. Однако для Малера это не шаг назад, а новый этап поисков. На этот раз художник хочет воплотить волнующие его мысли в сложившейся еще у Бетховена и отшлифованной десятилетиями творчества разных композиторов форме.

Как правило, замыслы его всегда очень конкретны. Но если раньше композитор давал слушателям путеводную мысль, то теперь он категорически отказывается от этого. Причину Малер раскрывает в одном из писем: «Название… было попыткой как раз дать для немузыкантов отправную точку и путеводитель для восприятия. Что это мне не удалось (как я ни старался) и только привело ко всяким кривотолкам, стало мне, увы, ясно слишком скоро. Подобная неудача постигала меня и раньше в сходных случаях, и я отныне окончательно отказался комментировать свои сочинения, анализировать их или давать какие-либо пособия».

О содержании Шестой Малер никому не сообщает ни слова: пусть те, кто хочет проникнуть в смысл его концепции, сами вдумываются, вслушиваются в музыку. «Моя Шестая, кажется, снова оказалась твердым орешком, который не в силах раскусить слабые зубки нашей критики», — восклицает композитор. Недаром еще раньше в одном из его писем появились такие строки: «Начиная с Бетховена, нет такой новой музыки, которая не имела бы внутренней программы. Но ничего не стоит такая музыка, о которой слушателю нужно сперва сообщить, какие чувства в ней заключены, и, соответственно, что он сам обязан почувствовать! Итак, еще раз, pereat (да сгинет. — Л. М.) — всякая программа! Нужно просто принести с собой уши и сердце и — тоже не последнее дело — добровольно отдаться рапсоду. Какой-то остаток мистерии есть всегда даже для самого автора!»

Но и без авторских пояснений содержание симфонии, не случайно получившей наименование Трагической, «вычитывается» из музыки. Замечательный дирижер, один из лучших интерпретаторов малеровской музыки Биллем Менгельберг писал о Шестой: «В ней передана потрясающая драма в звуках, титаническая борьба героя, гибнущего в страшной катастрофе». Малер ответил Менгельбергу: «Сердечно благодарю Вас за Ваше любезное письмо. Для меня оно очень ценно: ведь это большое утешение — услышать слова подлинного и глубокого понимания…»

Несмотря на трагизм, музыка симфонии не пессимистична. Это рассказ о герое, который борется отчаянно. И гибель его не напрасна: своим примером он вдохновит тех, кто придет ему на смену. Это —

действительно герой, а не просто главный персонаж. Вот почему финал вызывает ассоциации с траурными частями бетховенских симфоний, полными суровой мощи и скорбного величия.

Симфония была впервые исполнена 27 мая 1906 года в Эссене под управлением автора.

Музыка

Первая часть — типичное для Малера широко развернутое полотно, богатое контрастными образами, наполненное борьбой. Начало ее — четкое движение марша. На фоне железного ритма, словно стиснутые его жесткими рамками, взлетают вверх и ниспадают выразительные мелодии скрипок и деревянных духовых. Широко и мужественно звучат напевы медных духовых инструментов. Затухает, будто растворяется главная партия. На фоне барабанной дроби и громких сухих ударов литавр трубы интонируют мажорное трезвучие, которое переходит в минорное, словно не в силах удержаться, сползает, омрачается. Это свое образный лейтмотив, «девиз» симфонии, который проходит через все части как стержень, скрепляющий их единой мыслью. Спокойный отрешенный хорал с господствующим тембром деревянных — небольшая передышка. И вот уже захлестнул поток экспрессивнейшей мелодии побочной партии в гибком переплетении различных оркестровых голосов. Временами прорывается ритм марша. Но вновь все затухает. Окончилась экспозиция. Дальнейшее развитие музыки первой части основано на материале экспозиции. В ней есть и лирические эпизоды, моменты просветления, созерцания, но в основном это бурное, насыщенное драматизмом действие.

Вторая часть — мощное скерцо. Многочисленные темы рисуют огромную гротесковую картину. Первая тема скерцо — тупая, однообразная, с нарочитыми подчеркиваниями сильных долей такта, с бесконечными повторами. В начале второй темы в партитуре ремарка композитора: «Altfaeterisch» — старомодно. И тут же соло гобоя — «рассудительно, степенно». Безнадежной сытой ограниченностью веет от этой музыки. Временами, когда разрастается звучность, делается страшно. Кажется, что перед нами огромное болото благополучного мещанского существования, болото, которое в силах засосать, похоронить в себе высокие стремления, благородные порывы. В конце части несколько раз звучит лейтмотив симфонии — чередование мажорного и минорного аккордов у медных инструментов. (Форма скерцо — излюбленная композитором двойная трехчастная, усложненная появлением дополнительного эпизода в момент ожидаемой репризы.)

Третья часть, очень небольшая по размерам, является лирико-философским центром симфонии. Скрипки запевают нежную и выразительную мелодию. Ее подхватывает гобой, потом она вновь переходит к скрипкам. За ними вступают деревянные духовые. Гибка и прозрачна оркестровка, точно кружево плетется из тончайших линий. Следующий эпизод — пасторальный. Спокойно, безмятежно, как голоса природы, звучат наигрыши гобоя, кларнета, валторны. Но недолго. Лишь какой-то момент длится спокойствие. Его вновь сменяет эмоционально напряженный эпизод. На чередовании экстатических взлетов и затуханий и построена часть (снова в двойной трехчастной форме).

Финал — монументальный, почти равный по протяженности всем остальным частям, являет собою картину разворачивающейся борьбы. Это огромная, новаторски решенная сонатная форма, в которой все привычные разделы условны и многозначны. Звучит аккордовый лейтмотив симфонии. Патетична тема скрипок, мрачны и зловещи отрывки той же мелодии в низком регистре — у трубы, бас-кларнета, фаготов. Вот у валторны прозвучала более протяженная и более четко собранная мелодия, но растворилась в колеблющемся, мерцающем фоне. Траурным хоралом вступает духовая группа. Еще раз слышится лейтмотив. Очень медленно идет собирание сил, нарастание движения; подготавливается мощный решительный марш — первая, но далеко еще не высшая кульминация финала. Спадает волна. За ней накатывается следующая, затем еще и еще… Грациозные светлые эпизоды чередуются с взволнованной лирикой, патетические возгласы — с четким маршевым шагом. В кульминациях напряжение таково, что его трудно выдержать. Заключение симфонии мрачно. Удары литавр, лейтмотив. Тяжело звучит тема у перекликающихся тромбонов и тубы. Все медленнее и медленнее движение. И в последний раз — мрачный аккорд на фоне траурных ударов.

Л. Михеева

реклама

вам может быть интересно

Публикации