This article is about the chemical element. For the nutrient commonly called sodium, see salt. For the use of sodium as a medication, see Saline (medicine). For other uses, see sodium (disambiguation).

Sodium, 11Na| Sodium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | silvery white metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Na) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 370.944 K (97.794 °C, 208.029 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1156.090 K (882.940 °C, 1621.292 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 0.968 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.927 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 2573 K, 35 MPa (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.60 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 97.42 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 28.230 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, 0,[2] +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.93 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 186 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 166±9 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 227 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of sodium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3200 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 71 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 142 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 47.7 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +16.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 10 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 3.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 6.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 0.69 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-23-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Humphry Davy (1807) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Na»: from New Latin natrium, coined from German Natron, ‘natron’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of sodium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Category: Sodium

| references |

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin natrium) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable isotope is 23Na. The free metal does not occur in nature, and must be prepared from compounds. Sodium is the sixth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust and exists in numerous minerals such as feldspars, sodalite, and halite (NaCl). Many salts of sodium are highly water-soluble: sodium ions have been leached by the action of water from the Earth’s minerals over eons, and thus sodium and chlorine are the most common dissolved elements by weight in the oceans.

Sodium was first isolated by Humphry Davy in 1807 by the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide. Among many other useful sodium compounds, sodium hydroxide (lye) is used in soap manufacture, and sodium chloride (edible salt) is a de-icing agent and a nutrient for animals including humans.

Sodium is an essential element for all animals and some plants. Sodium ions are the major cation in the extracellular fluid (ECF) and as such are the major contributor to the ECF osmotic pressure and ECF compartment volume.[citation needed] Loss of water from the ECF compartment increases the sodium concentration, a condition called hypernatremia. Isotonic loss of water and sodium from the ECF compartment decreases the size of that compartment in a condition called ECF hypovolemia.

By means of the sodium-potassium pump, living human cells pump three sodium ions out of the cell in exchange for two potassium ions pumped in; comparing ion concentrations across the cell membrane, inside to outside, potassium measures about 40:1, and sodium, about 1:10. In nerve cells, the electrical charge across the cell membrane enables transmission of the nerve impulse—an action potential—when the charge is dissipated; sodium plays a key role in that activity.

Characteristics

Physical

Sodium at standard temperature and pressure is a soft silvery metal that combines with oxygen in the air and forms grayish white sodium oxide unless immersed in oil or inert gas, which are the conditions it is usually stored in. Sodium metal can be easily cut with a knife and is a good conductor of electricity and heat because it has only one electron in its valence shell, resulting in weak metallic bonding and free electrons, which carry energy. Due to having low atomic mass and large atomic radius, sodium is third-least dense of all elemental metals and is one of only three metals that can float on water, the other two being lithium and potassium.[5]

The melting (98 °C) and boiling (883 °C) points of sodium are lower than those of lithium but higher than those of the heavier alkali metals potassium, rubidium, and caesium, following periodic trends down the group.[6] These properties change dramatically at elevated pressures: at 1.5 Mbar, the color changes from silvery metallic to black; at 1.9 Mbar the material becomes transparent with a red color; and at 3 Mbar, sodium is a clear and transparent solid. All of these high-pressure allotropes are insulators and electrides.[7]

A positive flame test for sodium has a bright yellow color.

In a flame test, sodium and its compounds glow yellow[8] because the excited 3s electrons of sodium emit a photon when they fall from 3p to 3s; the wavelength of this photon corresponds to the D line at about 589.3 nm. Spin-orbit interactions involving the electron in the 3p orbital split the D line into two, at 589.0 and 589.6 nm; hyperfine structures involving both orbitals cause many more lines.[9]

Isotopes

Twenty isotopes of sodium are known, but only 23Na is stable. 23Na is created in the carbon-burning process in stars by fusing two carbon atoms together; this requires temperatures above 600 megakelvins and a star of at least three solar masses.[10] Two radioactive, cosmogenic isotopes are the byproduct of cosmic ray spallation: 22Na has a half-life of 2.6 years and 24Na, a half-life of 15 hours; all other isotopes have a half-life of less than one minute.[11]

Two nuclear isomers have been discovered, the longer-lived one being 24mNa with a half-life of around 20.2 milliseconds. Acute neutron radiation, as from a nuclear criticality accident, converts some of the stable 23Na in human blood to 24Na; the neutron radiation dosage of a victim can be calculated by measuring the concentration of 24Na relative to 23Na.[12]

Chemistry

Sodium atoms have 11 electrons, one more than the stable configuration of the noble gas neon. The first and second ionization energies are 495.8 kJ/mol and 4562 kJ/mol, respectively. As a result, sodium usually forms ionic compounds involving the Na+ cation.[13]

Metallic sodium

Metallic sodium is generally less reactive than potassium and more reactive than lithium.[14] Sodium metal is highly reducing, with the standard reduction potential for the Na+/Na couple being −2.71 volts,[15] though potassium and lithium have even more negative potentials.[16]

The thermal, fluidic, chemical, and nuclear properties of molten sodium metal have caused it to be one of the main coolants of choice for the fast breeder reactor. Such nuclear reactors are seen as a crucial step for the production of clean energy.[17]

Salts and oxides

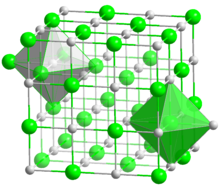

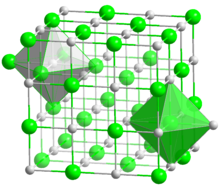

The structure of sodium chloride, showing octahedral coordination around Na+ and Cl− centres. This framework disintegrates when dissolved in water and reassembles when the water evaporates.

Sodium compounds are of immense commercial importance, being particularly central to industries producing glass, paper, soap, and textiles.[18] The most important sodium compounds are table salt (NaCl), soda ash (Na2CO3), baking soda (NaHCO3), caustic soda (NaOH), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), di- and tri-sodium phosphates, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3·5H2O), and borax (Na2B4O7·10H2O).[19] In compounds, sodium is usually ionically bonded to water and anions and is viewed as a hard Lewis acid.[20]

Two equivalent images of the chemical structure of sodium stearate, a typical soap.

Most soaps are sodium salts of fatty acids. Sodium soaps have a higher melting temperature (and seem «harder») than potassium soaps.[19]

Like all the alkali metals, sodium reacts exothermically with water. The reaction produces caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and flammable hydrogen gas. When burned in air, it forms primarily sodium peroxide with some sodium oxide.[21]

Aqueous solutions

Sodium tends to form water-soluble compounds, such as halides, sulfates, nitrates, carboxylates and carbonates. The main aqueous species are the aquo complexes [Na(H2O)n]+, where n = 4–8; with n = 6 indicated from X-ray diffraction data and computer simulations.[22]

Direct precipitation of sodium salts from aqueous solutions is rare because sodium salts typically have a high affinity for water. An exception is sodium bismuthate (NaBiO3).[23] Because of the high solubility of its compounds, sodium salts are usually isolated as solids by evaporation or by precipitation with an organic antisolvent, such as ethanol; for example, only 0.35 g/L of sodium chloride will dissolve in ethanol.[24] Crown ethers, like 15-crown-5, may be used as a phase-transfer catalyst.[25]

Sodium content of samples is determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry or by potentiometry using ion-selective electrodes.[26]

Electrides and sodides

Like the other alkali metals, sodium dissolves in ammonia and some amines to give deeply colored solutions; evaporation of these solutions leaves a shiny film of metallic sodium. The solutions contain the coordination complex (Na(NH3)6)+, with the positive charge counterbalanced by electrons as anions; cryptands permit the isolation of these complexes as crystalline solids. Sodium forms complexes with crown ethers, cryptands and other ligands.[27]

For example, 15-crown-5 has a high affinity for sodium because the cavity size of 15-crown-5 is 1.7–2.2 Å, which is enough to fit the sodium ion (1.9 Å).[28][29] Cryptands, like crown ethers and other ionophores, also have a high affinity for the sodium ion; derivatives of the alkalide Na− are obtainable[30] by the addition of cryptands to solutions of sodium in ammonia via disproportionation.[31]

Organosodium compounds

The structure of the complex of sodium (Na+, shown in yellow) and the antibiotic monensin-A.

Many organosodium compounds have been prepared. Because of the high polarity of the C-Na bonds, they behave like sources of carbanions (salts with organic anions). Some well-known derivatives include sodium cyclopentadienide (NaC5H5) and trityl sodium ((C6H5)3CNa).[32] Sodium naphthalene, Na+[C10H8•]−, a strong reducing agent, forms upon mixing Na and naphthalene in ethereal solutions.[33]

Intermetallic compounds

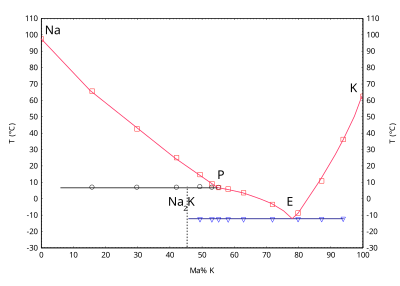

Sodium forms alloys with many metals, such as potassium, calcium, lead, and the group 11 and 12 elements. Sodium and potassium form KNa2 and NaK. NaK is 40–90% potassium and it is liquid at ambient temperature. It is an excellent thermal and electrical conductor. Sodium-calcium alloys are by-products of the electrolytic production of sodium from a binary salt mixture of NaCl-CaCl2 and ternary mixture NaCl-CaCl2-BaCl2. Calcium is only partially miscible with sodium, and the 1-2% of it dissolved in the sodium obtained from said mixtures can be precipitated by cooling to 120 °C and filtering.[34]

In a liquid state, sodium is completely miscible with lead. There are several methods to make sodium-lead alloys. One is to melt them together and another is to deposit sodium electrolytically on molten lead cathodes. NaPb3, NaPb, Na9Pb4, Na5Pb2, and Na15Pb4 are some of the known sodium-lead alloys. Sodium also forms alloys with gold (NaAu2) and silver (NaAg2). Group 12 metals (zinc, cadmium and mercury) are known to make alloys with sodium. NaZn13 and NaCd2 are alloys of zinc and cadmium. Sodium and mercury form NaHg, NaHg4, NaHg2, Na3Hg2, and Na3Hg.[35]

History

Because of its importance in human health, salt has long been an important commodity, as shown by the English word salary, which derives from salarium, the wafers of salt sometimes given to Roman soldiers along with their other wages. In medieval Europe, a compound of sodium with the Latin name of sodanum was used as a headache remedy. The name sodium is thought to originate from the Arabic suda, meaning headache, as the headache-alleviating properties of sodium carbonate or soda were well known in early times.[36]

Although sodium, sometimes called soda, had long been recognized in compounds, the metal itself was not isolated until 1807 by Sir Humphry Davy through the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide.[37][38] In 1809, the German physicist and chemist Ludwig Wilhelm Gilbert proposed the names Natronium for Humphry Davy’s «sodium» and Kalium for Davy’s «potassium».[39]

The chemical abbreviation for sodium was first published in 1814 by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in his system of atomic symbols,[40][41] and is an abbreviation of the element’s New Latin name natrium, which refers to the Egyptian natron,[36] a natural mineral salt mainly consisting of hydrated sodium carbonate. Natron historically had several important industrial and household uses, later eclipsed by other sodium compounds.[42]

Sodium imparts an intense yellow color to flames. As early as 1860, Kirchhoff and Bunsen noted the high sensitivity of a sodium flame test, and stated in Annalen der Physik und Chemie:[43]

In a corner of our 60 m3 room farthest away from the apparatus, we exploded 3 mg of sodium chlorate with milk sugar while observing the nonluminous flame before the slit. After a while, it glowed a bright yellow and showed a strong sodium line that disappeared only after 10 minutes. From the weight of the sodium salt and the volume of air in the room, we easily calculate that one part by weight of air could not contain more than 1/20 millionth weight of sodium.

Occurrence

The Earth’s crust contains 2.27% sodium, making it the seventh most abundant element on Earth and the fifth most abundant metal, behind aluminium, iron, calcium, and magnesium and ahead of potassium.[44] Sodium’s estimated oceanic abundance is 10.8 grams per liter.[45] Because of its high reactivity, it is never found as a pure element. It is found in many minerals, some very soluble, such as halite and natron, others much less soluble, such as amphibole and zeolite. The insolubility of certain sodium minerals such as cryolite and feldspar arises from their polymeric anions, which in the case of feldspar is a polysilicate.

Astronomical observations

Atomic sodium has a very strong spectral line in the yellow-orange part of the spectrum (the same line as is used in sodium-vapour street lights). This appears as an absorption line in many types of stars, including the Sun. The line was first studied in 1814 by Joseph von Fraunhofer during his investigation of the lines in the solar spectrum, now known as the Fraunhofer lines. Fraunhofer named it the «D» line, although it is now known to actually be a group of closely spaced lines split by a fine and hyperfine structure.[46]

The strength of the D line allows its detection in many other astronomical environments. In stars, it is seen in any whose surfaces are cool enough for sodium to exist in atomic form (rather than ionised). This corresponds to stars of roughly F-type and cooler. Many other stars appear to have a sodium absorption line, but this is actually caused by gas in the foreground interstellar medium. The two can be distinguished via high-resolution spectroscopy, because interstellar lines are much narrower than those broadened by stellar rotation.[47]

Sodium has also been detected in numerous Solar System environments, including Mercury’s atmosphere,[48] the exosphere of the Moon,[49] and numerous other bodies. Some comets have a sodium tail,[50] which was first detected in observations of Comet Hale–Bopp in 1997.[51] Sodium has even been detected in the atmospheres of some extrasolar planets via transit spectroscopy.[52]

Commercial production

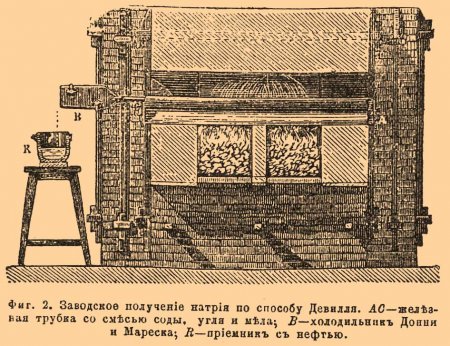

Employed only in rather specialized applications, only about 100,000 tonnes of metallic sodium are produced annually.[18] Metallic sodium was first produced commercially in the late 19th century[34] by carbothermal reduction of sodium carbonate at 1100 °C, as the first step of the Deville process for the production of aluminium:[53][54][55]

- Na2CO3 + 2 C → 2 Na + 3 CO

The high demand for aluminium created the need for the production of sodium. The introduction of the Hall–Héroult process for the production of aluminium by electrolysing a molten salt bath ended the need for large quantities of sodium. A related process based on the reduction of sodium hydroxide was developed in 1886.[53]

Sodium is now produced commercially through the electrolysis of molten sodium chloride, based on a process patented in 1924.[56][57] This is done in a Downs cell in which the NaCl is mixed with calcium chloride to lower the melting point below 700 °C.[58] As calcium is less electropositive than sodium, no calcium will be deposited at the cathode.[59] This method is less expensive than the previous Castner process (the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide).[60]

If sodium of high purity is required, it can be distilled once or several times.

The market for sodium is volatile due to the difficulty in its storage and shipping; it must be stored under a dry inert gas atmosphere or anhydrous mineral oil to prevent the formation of a surface layer of sodium oxide or sodium superoxide.[61]

Uses

Though metallic sodium has some important uses, the major applications for sodium use compounds; millions of tons of sodium chloride, hydroxide, and carbonate are produced annually. Sodium chloride is extensively used for anti-icing and de-icing and as a preservative; examples of the uses of sodium bicarbonate include baking, as a raising agent, and sodablasting. Along with potassium, many important medicines have sodium added to improve their bioavailability; though potassium is the better ion in most cases, sodium is chosen for its lower price and atomic weight.[62] Sodium hydride is used as a base for various reactions (such as the aldol reaction) in organic chemistry.

Metallic sodium is used mainly for the production of sodium borohydride, sodium azide, indigo, and triphenylphosphine. A once-common use was the making of tetraethyllead and titanium metal; because of the move away from TEL and new titanium production methods, the production of sodium declined after 1970.[18] Sodium is also used as an alloying metal, an anti-scaling agent,[63] and as a reducing agent for metals when other materials are ineffective.

Note the free element is not used as a scaling agent, ions in the water are exchanged for sodium ions. Sodium plasma («vapor») lamps are often used for street lighting in cities, shedding light that ranges from yellow-orange to peach as the pressure increases.[64] By itself or with potassium, sodium is a desiccant; it gives an intense blue coloration with benzophenone when the desiccate is dry.[65]

In organic synthesis, sodium is used in various reactions such as the Birch reduction, and the sodium fusion test is conducted to qualitatively analyse compounds.[66] Sodium reacts with alcohol and gives alkoxides, and when sodium is dissolved in ammonia solution, it can be used to reduce alkynes to trans-alkenes.[67][68] Lasers emitting light at the sodium D line are used to create artificial laser guide stars that assist in the adaptive optics for land-based visible-light telescopes.[69]

Heat transfer

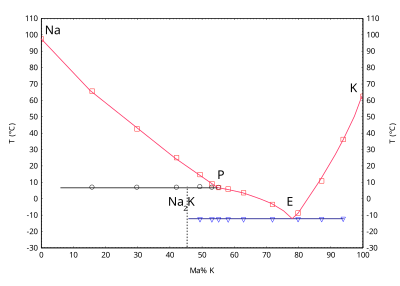

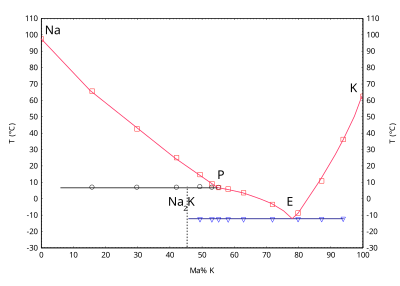

NaK phase diagram, showing the melting point of sodium as a function of potassium concentration. NaK with 77% potassium is eutectic and has the lowest melting point of the NaK alloys at −12.6 °C.[70]

Liquid sodium is used as a heat transfer fluid in sodium-cooled fast reactors[71] because it has the high thermal conductivity and low neutron absorption cross section required to achieve a high neutron flux in the reactor.[72] The high boiling point of sodium allows the reactor to operate at ambient (normal) pressure,[72] but drawbacks include its opacity, which hinders visual maintenance, and its strongly reducing properties. Sodium will explode in contact with water, although it will only burn gently in air. [73]

Radioactive sodium-24 may be produced by neutron bombardment during operation, posing a slight radiation hazard; the radioactivity stops within a few days after removal from the reactor.[74] If a reactor needs to be shut down frequently, NaK is used. Because NaK is a liquid at room temperature, the coolant does not solidify in the pipes.[75]

In this case, the pyrophoricity of potassium requires extra precautions to prevent and detect leaks.[76] Another heat transfer application is poppet valves in high-performance internal combustion engines; the valve stems are partially filled with sodium and work as a heat pipe to cool the valves.[77]

Biological role

Biological role in humans

In humans, sodium is an essential mineral that regulates blood volume, blood pressure, osmotic equilibrium and pH. The minimum physiological requirement for sodium is estimated to range from about 120 milligrams per day in newborns to 500 milligrams per day over the age of 10.[78]

Diet

Sodium chloride (salt) is the principal source of sodium in the diet, and is used as seasoning and preservative in such commodities as pickled preserves and jerky; for Americans, most sodium chloride comes from processed foods.[79] Other sources of sodium are its natural occurrence in food and such food additives as monosodium glutamate (MSG), sodium nitrite, sodium saccharin, baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), and sodium benzoate.[80]

The U.S. Institute of Medicine set its tolerable upper intake level for sodium at 2.3 grams per day,[81] but the average person in the United States consumes 3.4 grams per day.[82] The American Heart Association recommends no more than 1.5 g of sodium per day.[83]

High sodium consumption

High sodium consumption is unhealthy, and can lead to alteration in the mechanical performance of the heart.[84] High sodium consumption is also associated with chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke.[84]

High blood pressure

There is a strong correlation between higher sodium intake and higher blood pressure.[85] Studies have found that lowering sodium intake by 2 g per day tends to lower systolic blood pressure by about two to four mm Hg.[86] It has been estimated that such a decrease in sodium intake would lead to between 9 and 17% fewer cases of hypertension.[86]

Hypertension causes 7.6 million premature deaths worldwide each year.[87] (Note that salt contains about 39.3% sodium[88]—the rest being chlorine and trace chemicals; thus, 2.3 g sodium is about 5.9 g, or 5.3 ml, of salt—about one US teaspoon.[89][90])

One study found that people with or without hypertension who excreted less than 3 grams of sodium per day in their urine (and therefore were taking in less than 3 g/d) had a higher risk of death, stroke, or heart attack than those excreting 4 to 5 grams per day.[91] Levels of 7 g per day or more in people with hypertension were associated with higher mortality and cardiovascular events, but this was not found to be true for people without hypertension.[91] The US FDA states that adults with hypertension and prehypertension should reduce daily sodium intake to 1.5 g.[90]

Physiology

The renin–angiotensin system regulates the amount of fluid and sodium concentration in the body. Reduction of blood pressure and sodium concentration in the kidney result in the production of renin, which in turn produces aldosterone and angiotensin, which stimulates the reabsorption of sodium back into the bloodstream. When the concentration of sodium increases, the production of renin decreases, and the sodium concentration returns to normal.[92] The sodium ion (Na+) is an important electrolyte in neuron function, and in osmoregulation between cells and the extracellular fluid. This is accomplished in all animals by Na+/K+-ATPase, an active transporter pumping ions against the gradient, and sodium/potassium channels.[93] Sodium is the most prevalent metallic ion in extracellular fluid.[94]

In humans, unusually low or high sodium levels in the blood is recognized in medicine as hyponatremia and hypernatremia. These conditions may be caused by genetic factors, ageing, or prolonged vomiting or diarrhea.[95]

Biological role in plants

In C4 plants, sodium is a micronutrient that aids metabolism, specifically in regeneration of phosphoenolpyruvate and synthesis of chlorophyll.[96] In others, it substitutes for potassium in several roles, such as maintaining turgor pressure and aiding in the opening and closing of stomata.[97] Excess sodium in the soil can limit the uptake of water by decreasing the water potential, which may result in plant wilting; excess concentrations in the cytoplasm can lead to enzyme inhibition, which in turn causes necrosis and chlorosis.[98]

In response, some plants have developed mechanisms to limit sodium uptake in the roots, to store it in cell vacuoles, and restrict salt transport from roots to leaves.[99] Excess sodium may also be stored in old plant tissue, limiting the damage to new growth. Halophytes have adapted to be able to flourish in sodium rich environments.[99]

Safety and precautions

Sodium| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| Pictograms |   |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H260, H314 |

| Precautionary statements | P223, P231+P232, P280, P305+P351+P338, P370+P378, P422[100] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | [101]

3 2 2

|

Sodium forms flammable hydrogen and caustic sodium hydroxide on contact with water;[102] ingestion and contact with moisture on skin, eyes or mucous membranes can cause severe burns.[103][104] Sodium spontaneously explodes in the presence of water due to the formation of hydrogen (highly explosive) and sodium hydroxide (which dissolves in the water, liberating more surface). However, sodium exposed to air and ignited or reaching autoignition (reported to occur when a molten pool of sodium reaches about 290 °C, 554 °F)[105] displays a relatively mild fire.

In the case of massive (non-molten) pieces of sodium, the reaction with oxygen eventually becomes slow due to formation of a protective layer.[106] Fire extinguishers based on water accelerate sodium fires. Those based on carbon dioxide and bromochlorodifluoromethane should not be used on sodium fire.[104] Metal fires are Class D, but not all Class D extinguishers are effective when used to extinguish sodium fires. An effective extinguishing agent for sodium fires is Met-L-X.[104] Other effective agents include Lith-X, which has graphite powder and an organophosphate flame retardant, and dry sand.[107]

Sodium fires are prevented in nuclear reactors by isolating sodium from oxygen with surrounding pipes containing inert gas.[108] Pool-type sodium fires are prevented using diverse design measures called catch pan systems. They collect leaking sodium into a leak-recovery tank where it is isolated from oxygen.[108]

Liquid sodium fires are more dangerous to handle than solid sodium fires, particularly if there is insufficient experience with the safe handling of molten sodium. In a technical report for the United States Fire Administration,[109] R. J. Gordon writes (emphasis in original)

Once ignited, sodium is very difficult to extinguish. It will react violently with water, as noted previously, and with any extinguishing agent that contains water. It will also react with many other common extinguishing agents, including carbon dioxide and the halogen compounds and most dry chemical agents. The only safe and effective extinguishing agents are completely dry inert materials, such as Class D extinguishing agents, soda ash, graphite, diatomaceous earth, or sodium chloride, all of which can be used to bury a small quantity of burning sodium and exclude oxygen from reaching the metal.

The extinguishing agent must be absolutely dry, as even a trace of water in the material can react with the burning sodium to cause an explosion. Sodium chloride is recognized as an extinguishing medium because of its chemical stability, however it is hydroscopic (has the property of attracting and holding water molecules on the surface of the salt crystals) and must be kept absolutely dry to be used safely as an extinguishing agent. Every crystal of sodium chloride also contains a trace quantity of moisture within the structure of the crystal.

Molten sodium is extremely dangerous because it is much more reactive than a solid mass. In the liquid form, every sodium atom is free and mobile to instantaneously combine with any available oxygen atom or other oxidizer, and any gaseous by-product will be created as a rapidly

expanding gas bubble within the molten mass. Even a minute amount of water can create this type of reaction. Any amount of water introduced

into a pool of molten sodium is likely to cause a violent explosion inside the liquid mass, releasing the hydrogen as a rapidly expanding gas and causing the molten sodium to erupt from the container.When molten sodium is involved in a fire, the combustion occurs at the surface of the liquid. An inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon, can be used to form an inert layer over the pool of burning liquid sodium, but the gas must be applied very gently and contained over the surface. Except for soda ash, most of the powdered agents that are used to extinguish small fires in solid pieces or shallow pools will sink to the bottom of a molten mass of burning sodium — the sodium will float to the top and continue to burn. If the burning sodium is in a container, it may be feasible to extinguish the fire by placing a lid on the container to exclude oxygen.

See also

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Sodium». CIAAW. 2005.

- ^ The compound NaCl has been shown in experiments to exists in several unusual stoichiometries under high pressure, including Na3Cl in which contains a layer of sodium(0) atoms; see Zhang, W.; Oganov, A. R.; Goncharov, A. F.; Zhu, Q.; Boulfelfel, S. E.; Lyakhov, A. O.; Stavrou, E.; Somayazulu, M.; Prakapenka, V. B.; Konôpková, Z. (2013). «Unexpected Stable Stoichiometries of Sodium Chlorides». Science. 342 (6165): 1502–1505. arXiv:1310.7674. Bibcode:2013Sci…342.1502Z. doi:10.1126/science.1244989. PMID 24357316. S2CID 15298372.

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 75

- ^ ««Alkali Metals.» Science of Everyday Things». Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Gatti, M.; Tokatly, I.; Rubio, A. (2010). «Sodium: A Charge-Transfer Insulator at High Pressures». Physical Review Letters. 104 (21): 216404. arXiv:1003.0540. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104u6404G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.216404. PMID 20867123. S2CID 18359072.

- ^ Schumann, Walter (5 August 2008). Minerals of the World (2nd ed.). Sterling. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4027-5339-8. OCLC 637302667.

- ^ Citron, M. L.; Gabel, C.; Stroud, C.; Stroud, C. (1977). «Experimental Study of Power Broadening in a Two-Level Atom». Physical Review A. 16 (4): 1507–1512. Bibcode:1977PhRvA..16.1507C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.16.1507.

- ^ Denisenkov, P. A.; Ivanov, V. V. (1987). «Sodium Synthesis in Hydrogen Burning Stars». Soviet Astronomy Letters. 13: 214. Bibcode:1987SvAL…13..214D.

- ^ Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ Sanders, F. W.; Auxier, J. A. (1962). «Neutron Activation of Sodium in Anthropomorphous Phantoms». Health Physics. 8 (4): 371–379. doi:10.1097/00004032-196208000-00005. PMID 14496815. S2CID 38195963.

- ^ Lawrie Ryan; Roger Norris (31 July 2014). Cambridge International AS and A Level Chemistry Coursebook (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2014. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-107-63845-7.

- ^ De Leon, N. «Reactivity of Alkali Metals». Indiana University Northwest. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ^ Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio (2002). Physical Chemistry (7th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3539-7. OCLC 3345182.

- ^ Davies, Julian A. (1996). Synthetic Coordination Chemistry: Principles and Practice. World Scientific. p. 293. ISBN 978-981-02-2084-6. OCLC 717012347.

- ^ «Fast Neutron Reactors | FBR — World Nuclear Association». World-nuclear.org. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Alfred Klemm, Gabriele Hartmann, Ludwig Lange, «Sodium and Sodium Alloys» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_277

- ^ a b Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 931–943. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Cowan, James A. (1997). Inorganic Biochemistry: An Introduction. Wiley-VCH. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-471-18895-7. OCLC 34515430.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 84

- ^ Lincoln, S. F.; Richens, D. T.; Sykes, A. G. (2004). «Metal Aqua Ions». Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II. p. 515. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043748-6/01055-0. ISBN 978-0-08-043748-4.

- ^ Dean, John Aurie; Lange, Norbert Adolph (1998). Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-016384-3.

- ^ Burgess, J. (1978). Metal Ions in Solution. New York: Ellis Horwood. ISBN 978-0-85312-027-8.

- ^ Starks, Charles M.; Liotta, Charles L.; Halpern, Marc (1994). Phase-Transfer Catalysis: Fundamentals, Applications, and Industrial Perspectives. Chapman & Hall. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-412-04071-9. OCLC 28027599.

- ^ Levy, G. B. (1981). «Determination of Sodium with Ion-Selective Electrodes». Clinical Chemistry. 27 (8): 1435–1438. doi:10.1093/clinchem/27.8.1435. PMID 7273405. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Ivor L. Simmons, ed. (6 December 2012). Applications of the Newer Techniques of Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4684-3318-0.

- ^ Xu Hou, ed. (22 June 2016). Design, Fabrication, Properties and Applications of Smart and Advanced Materials (illustrated ed.). CRC Press, 2016. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4987-2249-0.

- ^ Nikos Hadjichristidis; Akira Hirao, eds. (2015). Anionic Polymerization: Principles, Practice, Strength, Consequences and Applications (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 349. ISBN 978-4-431-54186-8.

- ^ Dye, J. L.; Ceraso, J. M.; Mei Lok Tak; Barnett, B. L.; Tehan, F. J. (1974). «Crystalline Salt of the Sodium Anion (Na−)». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96 (2): 608–609. doi:10.1021/ja00809a060.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9. OCLC 48056955.

- ^ Renfrow, W. B. Jr.; Hauser, C. R. (1943). «Triphenylmethylsodium». Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 2, p. 607

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 111

- ^ a b Paul Ashworth; Janet Chetland (31 December 1991). Brian, Pearson (ed.). Speciality chemicals: Innovations in industrial synthesis and applications (illustrated ed.). London: Elsevier Applied Science. pp. 259–278. ISBN 978-1-85166-646-1. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Habashi, Fathi (21 November 2008). Alloys: Preparation, Properties, Applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. pp. 278–280. ISBN 978-3-527-61192-8.

- ^ a b Newton, David E. (1999). Baker, Lawrence W. (ed.). Chemical Elements. U·X·L. ISBN 978-0-7876-2847-5. OCLC 39778687.

- ^ Davy, Humphry (1808). «On some new phenomena of chemical changes produced by electricity, particularly the decomposition of the fixed alkalies, and the exhibition of the new substances which constitute their bases; and on the general nature of alkaline bodies». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 98: 1–44. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0001. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements. IX. Three alkali metals: Potassium, sodium, and lithium». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (6): 1035. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9.1035W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1035.

- ^ Humphry Davy (1809) «Ueber einige neue Erscheinungen chemischer Veränderungen, welche durch die Electricität bewirkt werden; insbesondere über die Zersetzung der feuerbeständigen Alkalien, die Darstellung der neuen Körper, welche ihre Basen ausmachen, und die Natur der Alkalien überhaupt» (On some new phenomena of chemical changes that are achieved by electricity; particularly the decomposition of flame-resistant alkalis [i.e., alkalies that cannot be reduced to their base metals by flames], the preparation of new substances that constitute their [metallic] bases, and the nature of alkalies generally), Annalen der Physik, 31 (2) : 113–175 ; see footnote p. 157. Archived 7 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine From p. 157: «In unserer deutschen Nomenclatur würde ich die Namen Kalium und Natronium vorschlagen, wenn man nicht lieber bei den von Herrn Erman gebrauchten und von mehreren angenommenen Benennungen Kali-Metalloid and Natron-Metalloid, bis zur völligen Aufklärung der chemischen Natur dieser räthzelhaften Körper bleiben will. Oder vielleicht findet man es noch zweckmässiger fürs Erste zwei Klassen zu machen, Metalle und Metalloide, und in die letztere Kalium und Natronium zu setzen. — Gilbert.» (In our German nomenclature, I would suggest the names Kalium and Natronium, if one would not rather continue with the appellations Kali-metalloid and Natron-metalloid which are used by Mr. Erman and accepted by several [people], until the complete clarification of the chemical nature of these puzzling substances. Or perhaps one finds it yet more advisable for the present to create two classes, metals and metalloids, and to place Kalium and Natronium in the latter – Gilbert.)

- ^ J. Jacob Berzelius, Försök, att, genom användandet af den electrokemiska theorien och de kemiska proportionerna, grundlägga ett rent vettenskapligt system för mineralogien [Attempt, by the use of electrochemical theory and chemical proportions, to found a pure scientific system for mineralogy] (Stockholm, Sweden: A. Gadelius, 1814), p. 87.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. «Elementymology & Elements Multidict». Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Shortland, Andrew; Schachner, Lukas; Freestone, Ian; Tite, Michael (2006). «Natron as a flux in the early vitreous materials industry: sources, beginnings and reasons for decline». Journal of Archaeological Science. 33 (4): 521–530. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.09.011.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1860). «Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen» (PDF). Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 186 (6): 161–189. Bibcode:1860AnP…186..161K. doi:10.1002/andp.18601860602. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 69.

- ^ Lide, David R. (19 June 2003). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 84th Edition. CRC Handbook. CRC Press. 14: Abundance of Elements in the Earth’s Crust and in the Sea. ISBN 978-0-8493-0484-2. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ «D-lines». Encyclopedia Britannica. spectroscopy. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Welty, Daniel E.; Hobbs, L. M.; Kulkarni, Varsha P. (1994). «A high-resolution survey of interstellar Na I D1 lines». The Astrophysical Journal. 436: 152. Bibcode:1994ApJ…436..152W. doi:10.1086/174889.

- ^ «Mercury». NASA Solar System Exploration. In Depth. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Colaprete, A.; Sarantos, M.; Wooden, D. H.; Stubbs, T. J.; Cook, A. M.; Shirley, M. (2015). «How surface composition and meteoroid impacts mediate sodium and potassium in the lunar exosphere». Science. 351 (6270): 249–252. Bibcode:2016Sci…351..249C. doi:10.1126/science.aad2380. PMID 26678876.

- ^ «Cometary neutral tail». astronomy.swin.edu.au. Cosmos. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Cremonese, G.; Boehnhardt, H.; Crovisier, J.; Rauer, H.; Fitzsimmons, A.; Fulle, M.; et al. (1997). «Neutral sodium from Comet Hale–Bopp: A third type of tail». The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 490 (2): L199–L202. arXiv:astro-ph/9710022. Bibcode:1997ApJ…490L.199C. doi:10.1086/311040. S2CID 119405749.

- ^ Redfield, Seth; Endl, Michael; Cochran, William D.; Koesterke, Lars (2008). «Sodium absorption from the exoplanetary atmosphere of HD 189733b detected in the optical transmission spectrum». The Astrophysical Journal. 673 (1): L87–L90. arXiv:0712.0761. Bibcode:2008ApJ…673L..87R. doi:10.1086/527475. S2CID 2028887.

- ^ a b Eggeman, Tim; Updated By Staff (2007). «Sodium and Sodium Alloys». Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1915040912051311.a01.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ Oesper, R. E.; Lemay, P. (1950). «Henri Sainte-Claire Deville, 1818–1881». Chymia. 3: 205–221. doi:10.2307/27757153. JSTOR 27757153.

- ^ Banks, Alton (1990). «Sodium». Journal of Chemical Education. 67 (12): 1046. Bibcode:1990JChEd..67.1046B. doi:10.1021/ed067p1046.

- ^ Pauling, Linus, General Chemistry, 1970 ed., Dover Publications

- ^ «Los Alamos National Laboratory – Sodium». Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Sodium production. Royal Society Of Chemistry. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Sodium Metal from France. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4578-1780-9.

- ^ Mark Anthony Benvenuto (24 February 2015). Industrial Chemistry: For Advanced Students (illustrated ed.). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015. ISBN 978-3-11-038339-3.

- ^ Stanley Nusim, ed. (19 April 2016). Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Development, Manufacturing, and Regulation, Second Edition (2, illustrated, revised ed.). CRC Press, 2016. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4398-0339-4.

- ^ Remington, Joseph P. (2006). Beringer, Paul (ed.). Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy (21st ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 365–366. ISBN 978-0-7817-4673-1. OCLC 60679584.

- ^ Harris, Jay C. (1949). Metal cleaning: bibliographical abstracts, 1842–1951. American Society for Testing and Materials. p. 76. OCLC 1848092. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Lindsey, Jack L. (1997). Applied illumination engineering. Fairmont Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-88173-212-2. OCLC 22184876. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Lerner, Leonid (16 February 2011). Small-Scale Synthesis of Laboratory Reagents with Reaction Modeling. CRC Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-4398-1312-6. OCLC 669160695. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Sethi, Arun (1 January 2006). Systematic Laboratory Experiments in Organic Chemistry. New Age International. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-81-224-1491-2. OCLC 86068991. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Smith, Michael (12 July 2011). Organic Synthesis (3 ed.). Academic Press, 2011. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-12-415884-9.

- ^ Solomons; Fryhle (2006). Organic Chemistry (8 ed.). John Wiley & Sons, 2006. p. 272. ISBN 978-81-265-1050-4.

- ^ «Laser Development for Sodium Laser Guide Stars at ESO» (PDF). Domenico Bonaccini Calia, Yan Feng, Wolfgang Hackenberg, Ronald Holzlöhner, Luke Taylor, Steffan Lewis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ van Rossen, G. L. C. M.; van Bleiswijk, H. (1912). «Über das Zustandsdiagramm der Kalium-Natriumlegierungen». Zeitschrift für Anorganische Chemie. 74: 152–156. doi:10.1002/zaac.19120740115. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Sodium as a Fast Reactor Coolant Archived 13 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine presented by Thomas H. Fanning. Nuclear Engineering Division. U.S. Department of Energy. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Topical Seminar Series on Sodium Fast Reactors. 3 May 2007

- ^ a b «Sodium-cooled Fast Reactor (SFR)» (PDF). Office of Nuclear Energy, U.S. Department of Energy. 18 February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Fire and Explosion Hazards. Research Publishing Service, 2011. 2011. p. 363. ISBN 978-981-08-7724-8.

- ^ Pavel Solomonovich Knopov; Panos M. Pardalos, eds. (2009). Simulation and Optimization Methods in Risk and Reliability Theory. Nova Science Publishers, 2009. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-60456-658-1.

- ^ McKillop, Allan A. (1976). Proceedings of the Heat Transfer and Fluid Mechanics Institute. Stanford University Press, 1976. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8047-0917-0.

- ^ U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Reactor Handbook: Engineering (2 ed.). Interscience Publishers. p. 325.

- ^ A US US2949907 A, Tauschek Max J, «Coolant-filled poppet valve and method of making same», published 23 August 1960

- ^ «Sodium» (PDF). Northwestern University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ «Sodium and Potassium Quick Health Facts». health.ltgovernors.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ «Sodium in diet». MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ «Reference Values for Elements». Dietary Reference Intakes Tables. Health Canada. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). p. 22. ISBN 978-0-16-087941-8. OCLC 738512922. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ «How much sodium should I eat per day?». American Heart Association. 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b Patel, Yash; Joseph, Jacob (13 December 2020). «Sodium Intake and Heart Failure». International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (24): 9474. doi:10.3390/ijms21249474. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7763082. PMID 33322108.

- ^ CDC (28 February 2018). «The links between sodium, potassium, and your blood pressure». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b Geleijnse, J. M.; Kok, F. J.; Grobbee, D. E. (2004). «Impact of dietary and lifestyle factors on the prevalence of hypertension in Western populations». European Journal of Public Health. 14 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.3.235. PMID 15369026.

- ^ Lawes, C. M.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Rodgers, A.; International Society of Hypertension (2008). «Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001» (PDF). Lancet. 371 (9623): 1513–1518. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.463.887. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. PMID 18456100. S2CID 19315480. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Armstrong, James (2011). General, Organic, and Biochemistry: An Applied Approach. Cengage Learning. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-1-133-16826-3.

- ^ Table Salt Conversion Archived 23 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Traditionaloven.com. Retrieved on 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b «Use the Nutrition Facts Label to Reduce Your Intake of Sodium in Your Diet». US Food and Drug Administration. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ a b Andrew Mente; et al. (2016). «Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies». The Lancet. 388 (10043): 465–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30467-6. hdl:10379/16625. PMID 27216139. S2CID 44581906.

- ^ McGuire, Michelle; Beerman, Kathy A. (2011). Nutritional Sciences: From Fundamentals to Food. Cengage Learning. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-324-59864-3. OCLC 472704484.

- ^ Campbell, Neil (1987). Biology. Benjamin/Cummings. p. 795. ISBN 978-0-8053-1840-1.

- ^ Srilakshmi, B. (2006). Nutrition Science (2nd ed.). New Age International. p. 318. ISBN 978-81-224-1633-6. OCLC 173807260. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^

Pohl, Hanna R.; Wheeler, John S.; Murray, H. Edward (2013). «Sodium and Potassium in Health and Disease». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 29–47. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_2. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470088. - ^ Kering, M. K. (2008). «Manganese Nutrition and Photosynthesis in NAD-malic enzyme C4 plants PhD dissertation» (PDF). University of Missouri-Columbia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Subbarao, G. V.; Ito, O.; Berry, W. L.; Wheeler, R. M. (2003). «Sodium—A Functional Plant Nutrient». Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 22 (5): 391–416. doi:10.1080/07352680390243495. S2CID 85111284.

- ^ Zhu, J. K. (2001). «Plant salt tolerance». Trends in Plant Science. 6 (2): 66–71. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0. PMID 11173290.

- ^ a b «Plants and salt ion toxicity». Plant Biology. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ «Sodium 262714». Sigma-Aldrich. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Hazard Rating Information for NFPA Fire Diamonds Archived 17 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Ehs.neu.edu. Retrieved on 11 November 2015.

- ^ Angelici, R. J. (1999). Synthesis and Technique in Inorganic Chemistry. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-48-4.

- ^ Routley, J. Gordon. Sodium Explosion Critically Burns Firefighters: Newton, Massachusetts. U. S. Fire Administration. FEMA, 2013.

- ^ a b c Prudent Practices in the Laboratory: Handling and Disposal of Chemicals. National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Prudent Practices for Handling, Storage, and Disposal of Chemicals in Laboratories. National Academies, 1995. 1995. p. 390. ISBN 9780309052290.

- ^ An, Deukkwang; Sunderland, Peter B.; Lathrop, Daniel P. (2013). «Suppression of sodium fires with liquid nitrogen» (PDF). Fire Safety Journal. 58: 204–207. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2013.02.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017.

- ^ Clough, W. S.; Garland, J. A. (1 July 1970). Behaviour in the Atmosphere of the Aerosol from a Sodium Fire (Report). U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. OSTI 4039364.

- ^ Ladwig, Thomas H. (1991). Industrial fire prevention and protection. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-442-23678-6.

- ^ a b Günter Kessler (8 May 2012). Sustainable and Safe Nuclear Fission Energy: Technology and Safety of Fast and Thermal Nuclear Reactors (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. p. 446. ISBN 978-3-642-11990-3.

- ^ Gordon, Routley J. (25 October 1993). Sodium explosion critically burns firefighters, Newton, Massachusetts (Technical report). United States Fire Administration. 75.

{{cite techreport}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Bibliography

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

External links

![]()

Wikiquote has quotations related to Sodium.

- Sodium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Etymology of «natrium» – source of symbol Na

- The Wooden Periodic Table Table’s Entry on Sodium

- Sodium isotopes data from The Berkeley Laboratory Isotopes Project’s

This article is about the chemical element. For the nutrient commonly called sodium, see salt. For the use of sodium as a medication, see Saline (medicine). For other uses, see sodium (disambiguation).

Sodium, 11Na| Sodium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | silvery white metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Na) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 370.944 K (97.794 °C, 208.029 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1156.090 K (882.940 °C, 1621.292 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 0.968 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.927 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 2573 K, 35 MPa (extrapolated) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.60 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 97.42 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 28.230 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, 0,[2] +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.93 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 186 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 166±9 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 227 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of sodium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3200 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 71 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 142 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 47.7 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +16.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 10 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 3.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 6.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 0.69 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-23-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Humphry Davy (1807) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Na»: from New Latin natrium, coined from German Natron, ‘natron’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of sodium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Category: Sodium

| references |

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin natrium) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable isotope is 23Na. The free metal does not occur in nature, and must be prepared from compounds. Sodium is the sixth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust and exists in numerous minerals such as feldspars, sodalite, and halite (NaCl). Many salts of sodium are highly water-soluble: sodium ions have been leached by the action of water from the Earth’s minerals over eons, and thus sodium and chlorine are the most common dissolved elements by weight in the oceans.

Sodium was first isolated by Humphry Davy in 1807 by the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide. Among many other useful sodium compounds, sodium hydroxide (lye) is used in soap manufacture, and sodium chloride (edible salt) is a de-icing agent and a nutrient for animals including humans.

Sodium is an essential element for all animals and some plants. Sodium ions are the major cation in the extracellular fluid (ECF) and as such are the major contributor to the ECF osmotic pressure and ECF compartment volume.[citation needed] Loss of water from the ECF compartment increases the sodium concentration, a condition called hypernatremia. Isotonic loss of water and sodium from the ECF compartment decreases the size of that compartment in a condition called ECF hypovolemia.

By means of the sodium-potassium pump, living human cells pump three sodium ions out of the cell in exchange for two potassium ions pumped in; comparing ion concentrations across the cell membrane, inside to outside, potassium measures about 40:1, and sodium, about 1:10. In nerve cells, the electrical charge across the cell membrane enables transmission of the nerve impulse—an action potential—when the charge is dissipated; sodium plays a key role in that activity.

Characteristics

Physical

Sodium at standard temperature and pressure is a soft silvery metal that combines with oxygen in the air and forms grayish white sodium oxide unless immersed in oil or inert gas, which are the conditions it is usually stored in. Sodium metal can be easily cut with a knife and is a good conductor of electricity and heat because it has only one electron in its valence shell, resulting in weak metallic bonding and free electrons, which carry energy. Due to having low atomic mass and large atomic radius, sodium is third-least dense of all elemental metals and is one of only three metals that can float on water, the other two being lithium and potassium.[5]

The melting (98 °C) and boiling (883 °C) points of sodium are lower than those of lithium but higher than those of the heavier alkali metals potassium, rubidium, and caesium, following periodic trends down the group.[6] These properties change dramatically at elevated pressures: at 1.5 Mbar, the color changes from silvery metallic to black; at 1.9 Mbar the material becomes transparent with a red color; and at 3 Mbar, sodium is a clear and transparent solid. All of these high-pressure allotropes are insulators and electrides.[7]

A positive flame test for sodium has a bright yellow color.

In a flame test, sodium and its compounds glow yellow[8] because the excited 3s electrons of sodium emit a photon when they fall from 3p to 3s; the wavelength of this photon corresponds to the D line at about 589.3 nm. Spin-orbit interactions involving the electron in the 3p orbital split the D line into two, at 589.0 and 589.6 nm; hyperfine structures involving both orbitals cause many more lines.[9]

Isotopes

Twenty isotopes of sodium are known, but only 23Na is stable. 23Na is created in the carbon-burning process in stars by fusing two carbon atoms together; this requires temperatures above 600 megakelvins and a star of at least three solar masses.[10] Two radioactive, cosmogenic isotopes are the byproduct of cosmic ray spallation: 22Na has a half-life of 2.6 years and 24Na, a half-life of 15 hours; all other isotopes have a half-life of less than one minute.[11]

Two nuclear isomers have been discovered, the longer-lived one being 24mNa with a half-life of around 20.2 milliseconds. Acute neutron radiation, as from a nuclear criticality accident, converts some of the stable 23Na in human blood to 24Na; the neutron radiation dosage of a victim can be calculated by measuring the concentration of 24Na relative to 23Na.[12]

Chemistry

Sodium atoms have 11 electrons, one more than the stable configuration of the noble gas neon. The first and second ionization energies are 495.8 kJ/mol and 4562 kJ/mol, respectively. As a result, sodium usually forms ionic compounds involving the Na+ cation.[13]

Metallic sodium

Metallic sodium is generally less reactive than potassium and more reactive than lithium.[14] Sodium metal is highly reducing, with the standard reduction potential for the Na+/Na couple being −2.71 volts,[15] though potassium and lithium have even more negative potentials.[16]

The thermal, fluidic, chemical, and nuclear properties of molten sodium metal have caused it to be one of the main coolants of choice for the fast breeder reactor. Such nuclear reactors are seen as a crucial step for the production of clean energy.[17]

Salts and oxides

The structure of sodium chloride, showing octahedral coordination around Na+ and Cl− centres. This framework disintegrates when dissolved in water and reassembles when the water evaporates.

Sodium compounds are of immense commercial importance, being particularly central to industries producing glass, paper, soap, and textiles.[18] The most important sodium compounds are table salt (NaCl), soda ash (Na2CO3), baking soda (NaHCO3), caustic soda (NaOH), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), di- and tri-sodium phosphates, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3·5H2O), and borax (Na2B4O7·10H2O).[19] In compounds, sodium is usually ionically bonded to water and anions and is viewed as a hard Lewis acid.[20]

Two equivalent images of the chemical structure of sodium stearate, a typical soap.

Most soaps are sodium salts of fatty acids. Sodium soaps have a higher melting temperature (and seem «harder») than potassium soaps.[19]

Like all the alkali metals, sodium reacts exothermically with water. The reaction produces caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and flammable hydrogen gas. When burned in air, it forms primarily sodium peroxide with some sodium oxide.[21]

Aqueous solutions

Sodium tends to form water-soluble compounds, such as halides, sulfates, nitrates, carboxylates and carbonates. The main aqueous species are the aquo complexes [Na(H2O)n]+, where n = 4–8; with n = 6 indicated from X-ray diffraction data and computer simulations.[22]

Direct precipitation of sodium salts from aqueous solutions is rare because sodium salts typically have a high affinity for water. An exception is sodium bismuthate (NaBiO3).[23] Because of the high solubility of its compounds, sodium salts are usually isolated as solids by evaporation or by precipitation with an organic antisolvent, such as ethanol; for example, only 0.35 g/L of sodium chloride will dissolve in ethanol.[24] Crown ethers, like 15-crown-5, may be used as a phase-transfer catalyst.[25]

Sodium content of samples is determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry or by potentiometry using ion-selective electrodes.[26]

Electrides and sodides

Like the other alkali metals, sodium dissolves in ammonia and some amines to give deeply colored solutions; evaporation of these solutions leaves a shiny film of metallic sodium. The solutions contain the coordination complex (Na(NH3)6)+, with the positive charge counterbalanced by electrons as anions; cryptands permit the isolation of these complexes as crystalline solids. Sodium forms complexes with crown ethers, cryptands and other ligands.[27]

For example, 15-crown-5 has a high affinity for sodium because the cavity size of 15-crown-5 is 1.7–2.2 Å, which is enough to fit the sodium ion (1.9 Å).[28][29] Cryptands, like crown ethers and other ionophores, also have a high affinity for the sodium ion; derivatives of the alkalide Na− are obtainable[30] by the addition of cryptands to solutions of sodium in ammonia via disproportionation.[31]

Organosodium compounds

The structure of the complex of sodium (Na+, shown in yellow) and the antibiotic monensin-A.

Many organosodium compounds have been prepared. Because of the high polarity of the C-Na bonds, they behave like sources of carbanions (salts with organic anions). Some well-known derivatives include sodium cyclopentadienide (NaC5H5) and trityl sodium ((C6H5)3CNa).[32] Sodium naphthalene, Na+[C10H8•]−, a strong reducing agent, forms upon mixing Na and naphthalene in ethereal solutions.[33]

Intermetallic compounds

Sodium forms alloys with many metals, such as potassium, calcium, lead, and the group 11 and 12 elements. Sodium and potassium form KNa2 and NaK. NaK is 40–90% potassium and it is liquid at ambient temperature. It is an excellent thermal and electrical conductor. Sodium-calcium alloys are by-products of the electrolytic production of sodium from a binary salt mixture of NaCl-CaCl2 and ternary mixture NaCl-CaCl2-BaCl2. Calcium is only partially miscible with sodium, and the 1-2% of it dissolved in the sodium obtained from said mixtures can be precipitated by cooling to 120 °C and filtering.[34]